Real-Driving Emissions of Euro 2–Euro 6 Vehicles in Poland—17 Years of Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Real-Driving Emissions Studies Worldwide

2.1. North America

2.2. Asia

2.3. Europe

2.4. Current Emission Limits and Regulatory Framework Evolution

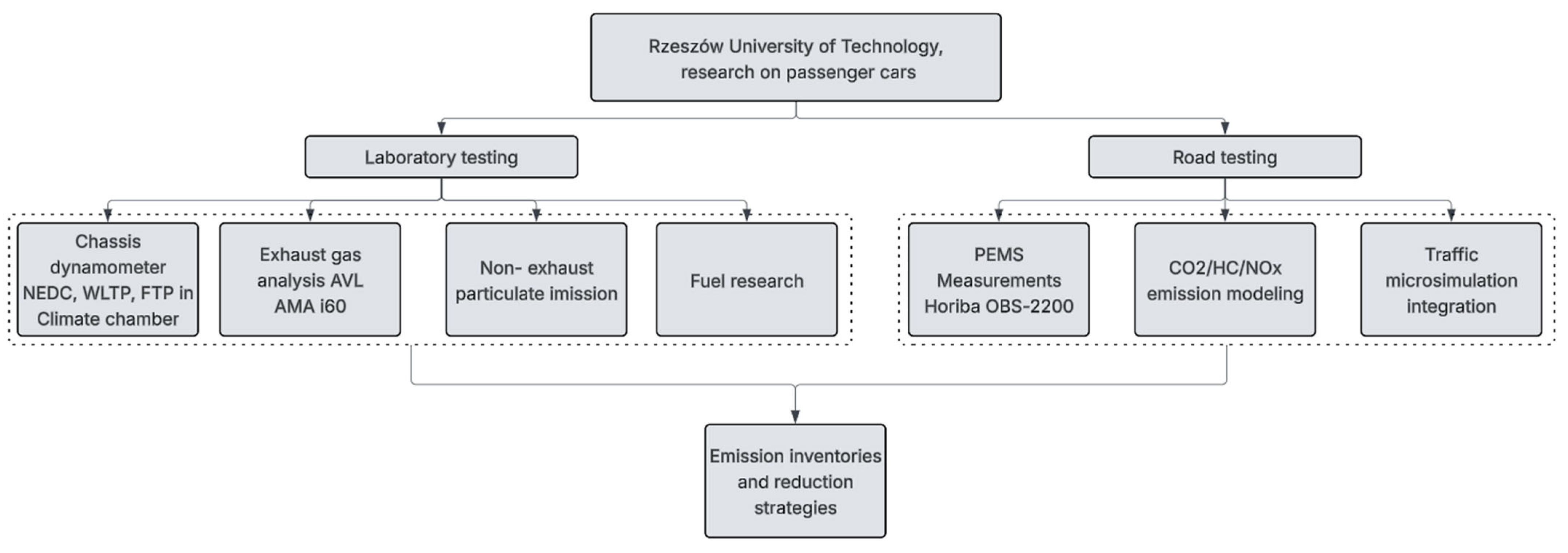

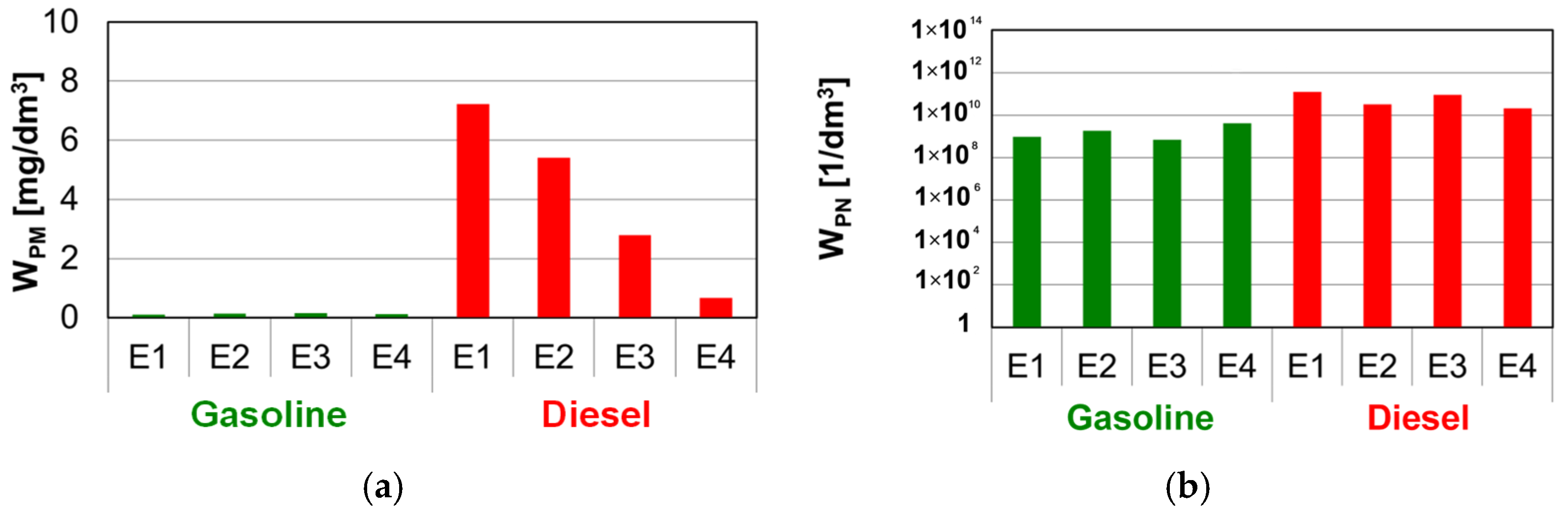

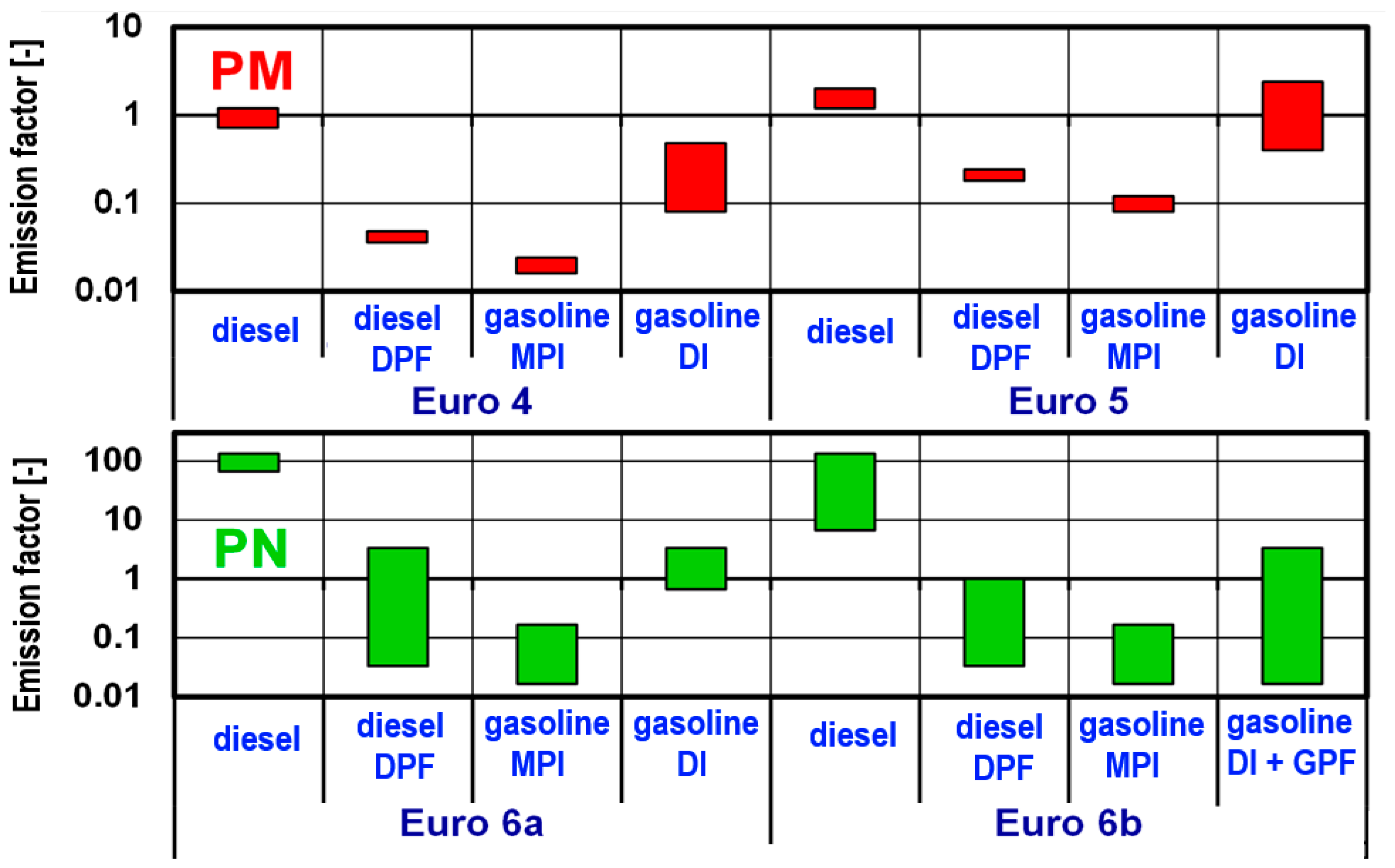

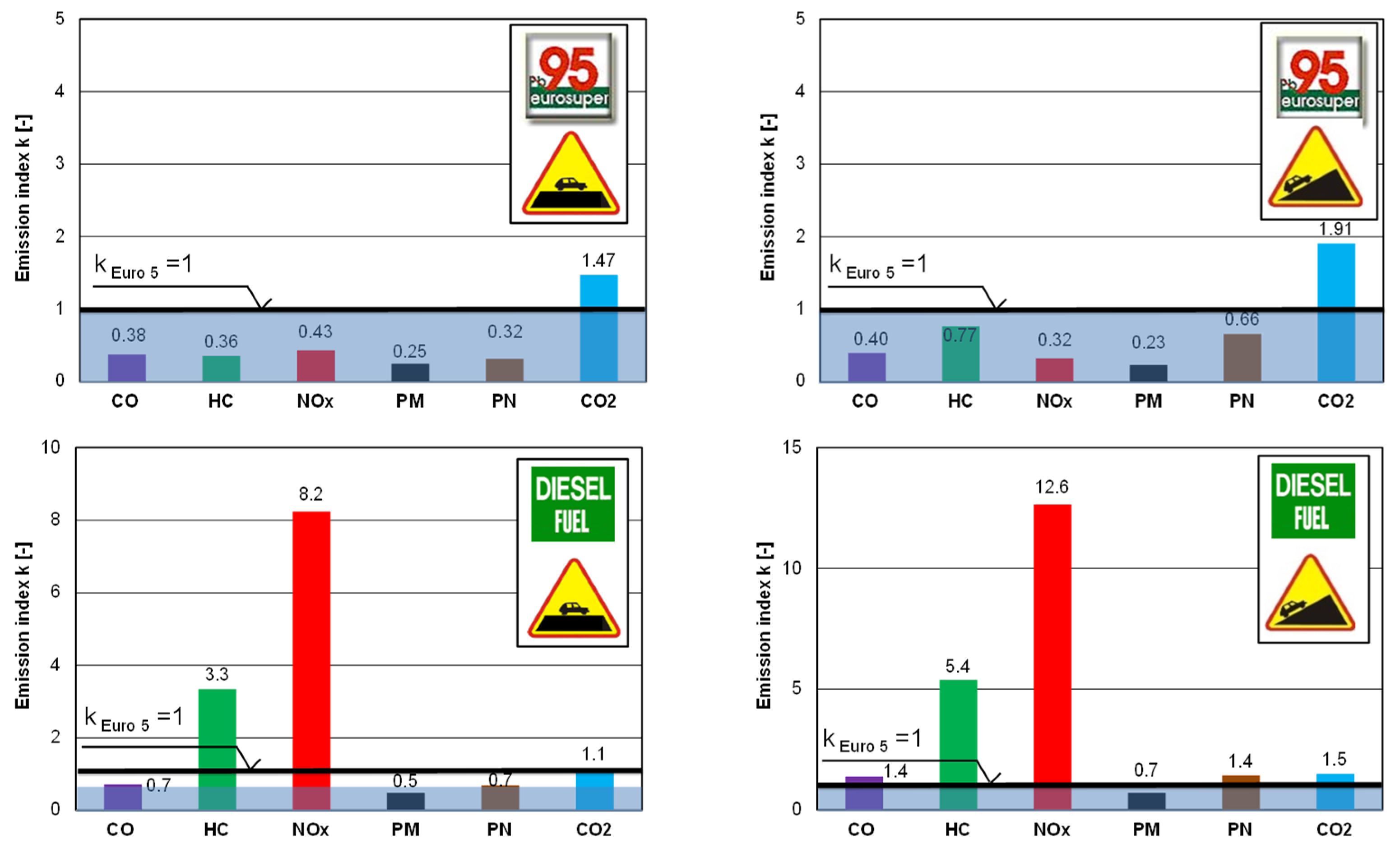

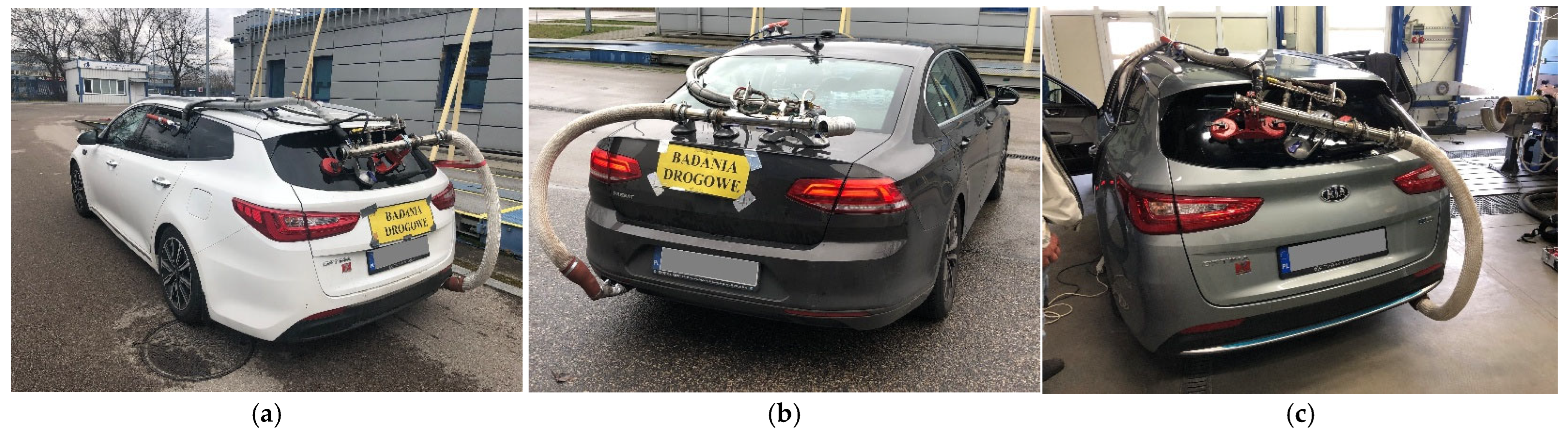

3. Research on Passenger Cars Conducted at the Rzeszów University of Technology

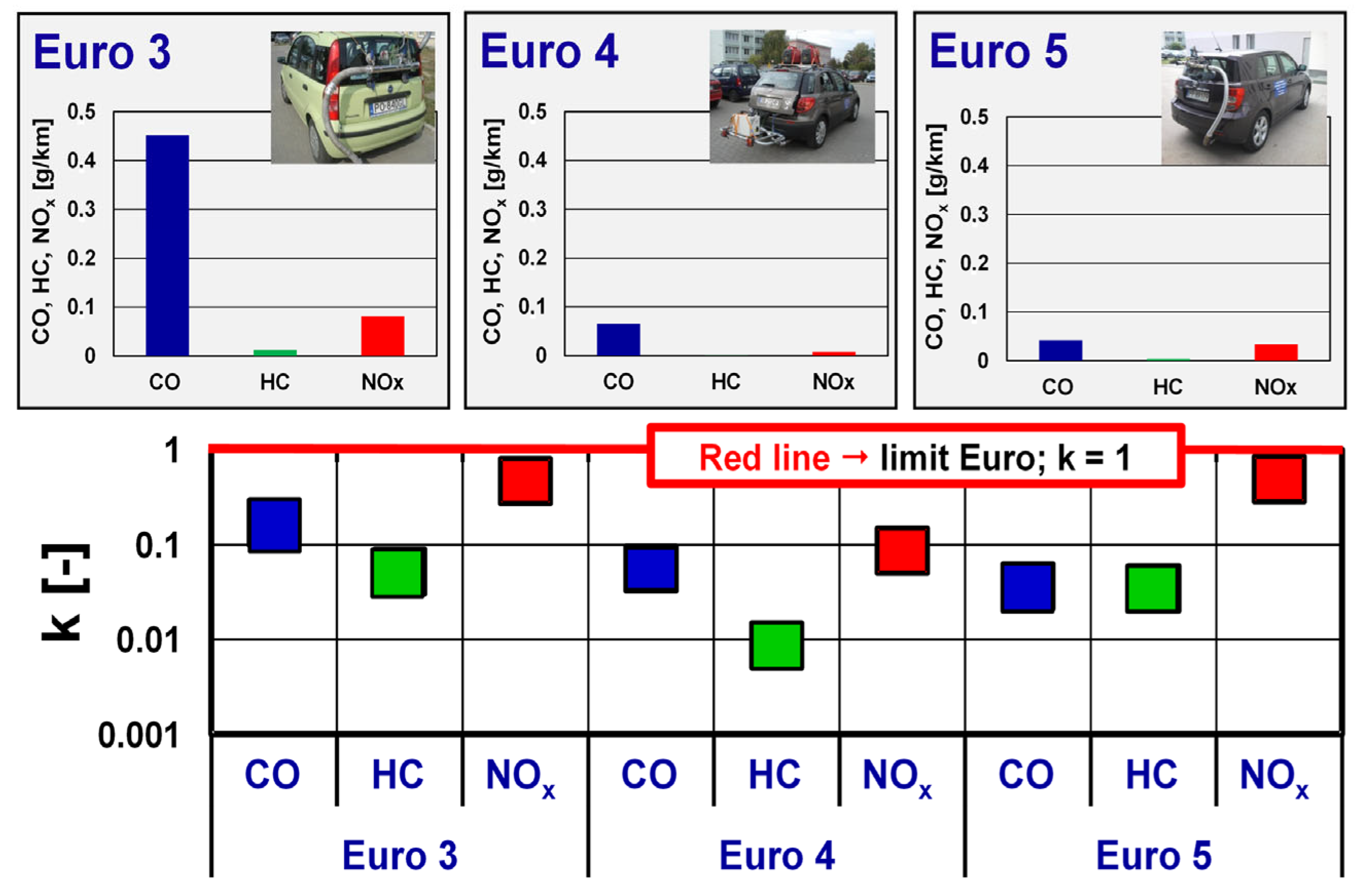

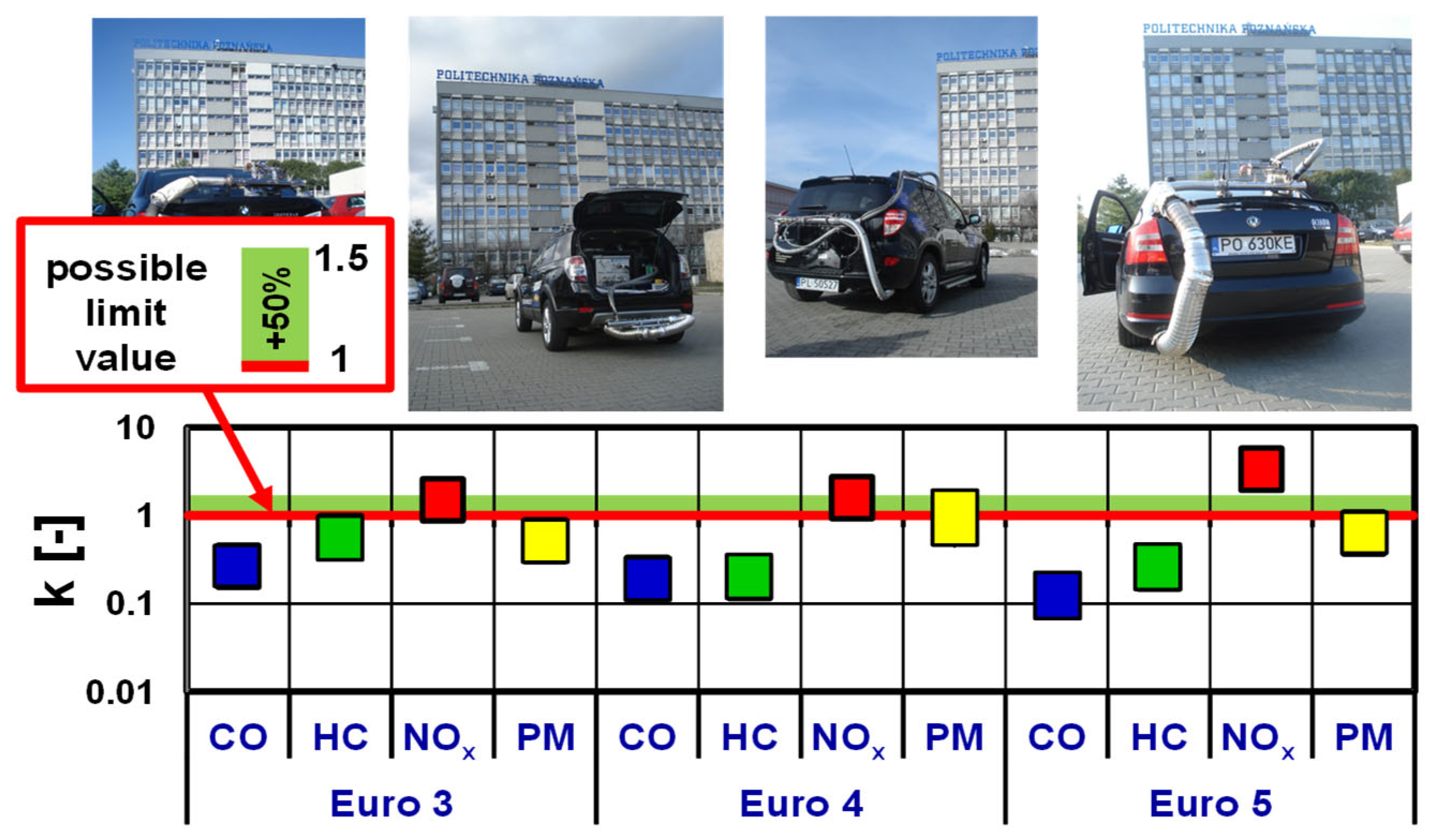

4. Exhaust-Emission Studies of Passenger Cars Conducted at Poznan University of Technology

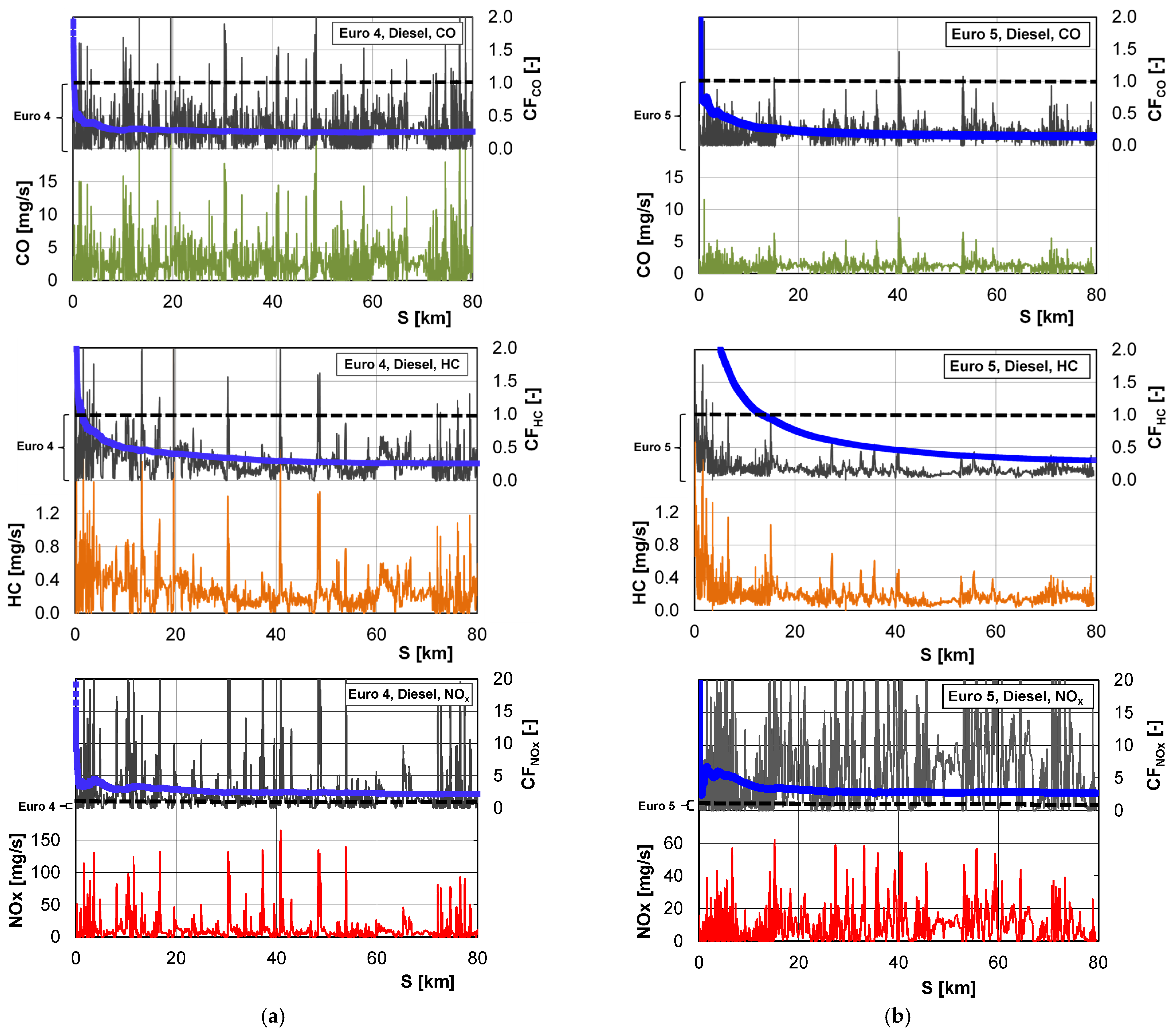

- The instantaneous value—characterized by high variability because it is calculated for each second of the test.

- The cumulative value—during the test, calculated as the current on-road emission of the given pollutant (from the start of the test to the current moment) relative to the normative value.

- The total-test value—defined as the ratio of the on-road emission measured in the real-world driving test to the corresponding normative value.

- For carbon monoxide—a very rapid increase during engine start-up, followed by a subsequent decrease; under real-world operating conditions, a satisfactory reduction below the required limit is achieved within a short period for vehicles meeting Euro 4 and Euro 5 standards; the indicator values are comparable for the tested vehicles.

- All vehicles met the Euro 6d-Temp requirements, and their emissions were significantly lower than the permissible limits.

- CO2 emissions were in the range of 60–80 g/km, confirming the high energy efficiency of PHEVs.

- NOx emissions were very low (3–8 mg/km), up to ten times below the regulatory limit.

- CO emissions were 10–20 times lower than the permissible limit.

- The particle-number emissions were far below the limit.

- The urban phase was characterized by zero CO2 emissions, as the vehicles operated exclusively in electric mode.

- The largest differences between the vehicles occurred in the rural and motorway phases, where the combustion engine engaged.

- At full battery charge (SOC = 100%), the results were CO2—12 g/km, CO—6 mg/km, NOx—1.8 mg/km, PN—1.8 × 1010 1/km,

- In the forced-charging mode (SOC = 0 → 100%), the results were CO2—over 300 g/km, CO—147 mg/km, NOx—22 mg/km, PN—2.0 × 1011 1/km.

- When the vehicle operated solely on the combustion engine (SOC = 0%), fuel consumption increased thirteenfold, and the emissions of CO, NOx, and PN rose by factors of 10, 6, and 4, respectively.

5. Real-Driving Emission Studies Conducted at the Motor Transport Institute in Warsaw

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAN | Control Area Network |

| CATARC | China Automotive Technology and Research Center |

| CERAM | Centre d’Essais et de Recherche Automobile de Mortefontaine |

| CF | Conformity Factors |

| CMG | China Merchants Group |

| CMVR | China Merchants Testing Vehicle Technology Research Institute |

| CNG | Compressed Natural Gas |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| CVCC | Constant-Volume Combustion Chamber |

| DEKRA | Deutsche Kraftfahrzeug-Überwachungs-Verein eV |

| DPF | Diesel Particulate Filter |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| FID | Flame Ionization Detector |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GPR | Gaussian Process Regression |

| GPS | Global Positioning Systems |

| GTR | Global Technical Regulations |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| HFRR | High-Frequency Reciprocating Rig |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engine |

| JARI | Japan Automobile Research Institute |

| JEVA | Japan Electric Vehicle Association |

| JRC | Joint Research Centre |

| JSK | Association of Electronic Technology for Automobile Traffic and Driving |

| KATECH | Korea Automotive Technology Institute |

| LCA | Life-Cycle Assessments |

| LPG | Liquefied Petroleum Gas |

| M | Motorway |

| MAW | Moving Average Window |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NDIR | Non-Dispersive Infrared |

| NEDC | New European Driving Cycle |

| NEEL | New Energy Engine Laboratory |

| NG | Natural Gas |

| NMHC | Non-Methane Hydrocarbons |

| NVFEL | National Vehicle and Fuel Emissions Laboratory |

| NVH | Noise, Vibration and Harshness |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| OBD | On-Board Diagnostic |

| PEMS | Portable Emissions Measurement System |

| PHEV | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter (<2.5 μm) |

| PM10 | Particulate Matter (<10 μm) |

| PN | Particle Number |

| R | Rural |

| RDE | Real-Driving Emissions |

| REV | Range-Extender Electric Vehicles |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RPA | Relative positive acceleration |

| SEMS | Smart Emissions Measurement System |

| SOC | State-of-Charge |

| SwRI | Southwest Research Institute |

| THC | Total Hydrocarbons |

| TNO | Nederlandse Organisatie voor Toegepast Natuurwetenschappelijk Onderzoek |

| TÜV | Technischer Überwachungsverein |

| U | Urban |

| UFP | Ultrafine Particles |

| UNECE | United Nations Economic Commission for Europe |

| URRC | Urban Road Cycle |

| US | United States |

| V | Velocity |

| V·a+[95] | 95th percentile of the product of vehicle speed and positive acceleration |

| VELA | Vehicle Emissions Laboratories |

| VERC | Vehicle Emissions Research Centre |

| WLTC | Worldwide harmonized Light-duty Test Cycle |

| WtW | Well-to-Wheel |

References

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 of 18 July 2008 Implementing and Amending Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Type-Approval of Motor Vehicles with Respect to Emissions from Light Passenger and Commercial Vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6) and on Access to Vehicle Repair and Maintenance Information. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2008/692/oj (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1151 of 1 June 2017 Supplementing Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Type-Approval of Motor Vehicles with Respect to Emissions from Light Passenger and Commercial Vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6) and on Access to Vehicle Repair and Maintenance Information, Amending Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 and Commission Regulation (EU) No 1230/2012 and Repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/1151/oj (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/427 of 10 March 2016 Amending Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 as Regards Emissions from Light Passenger and Commercial Vehicles (Euro 6)—RDE Package 1. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/427/oj (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/646 of 20 April 2016 Amending Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 as Regards Emissions from Light Passenger and Commercial Vehicles (Euro 6)—RDE Package 2. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/646/oj (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1154 of 7 June 2017 Amending Regulation (EU) 2017/1151 Supplementing Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Type-Approval of Motor Vehicles with Respect to Emissions from Light Passenger and Commercial Vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6) and on Access to Vehicle Repair and Maintenance Information, Amending Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 and Commission Regulation (EU) No 1230/2012 and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 and Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as Regards Real-Driving Emissions from Light Passenger and Commercial Vehicles (Euro 6)—RDE Package 3. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/1154/oj (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Commission Regulation (EU) 2018/1832 of 5 November 2018 Amending Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 and Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/1151 for the Purpose of Improving the Emission Type Approval Tests and Procedures for Light Passenger and Commercial Vehicles, Including Those for in-Service Conformity and Real-Driving Emissions and Introducing Devices for Monitoring the Consumption of Fuel and Electric Energy—RDE Package 4. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/1832/oj (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2019/631 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 Setting CO2 Emission Performance Standards for New Passenger Cars and for New Light Commercial Vehicles, and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 443/2009 and (EU) No 510/2011 (Recast). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/631/oj (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on Type-Approval of Motor Vehicles and Engines and of Systems, Components and Separate Technical Units Intended for Such Vehicles, with Respect to Their Emissions and Battery Durability (Euro 7) and Repealing Regulations (EC) No 715/2007 and (EC) No 595/2009). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52022PC0586 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Publications Office of the European Union. Connection of Early Stage Smart Investors with Technology-Based Start-Ups in Innovation Ecosystems; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/0770 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Publications Office of the European Union. PEMS Based in-Service Testing—Practical Recommendations for Heavy-Duty Engines/Vehicles; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2790/959024 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Suarez-Bertoa, R.; Valverde, V.; Clairotte, M.; Pavlovic, J.; Giechaskiel, B.; Franco, V.; Kregar, Z.; Astorga, C. On-road emissions of passenger cars beyond the boundary conditions of the real-driving emissions test. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publications Office of the European Union. Assessment of a Real Driving Emissions Inter-Laboratory Correlation Circuit; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/3632769 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Publications Office of the European Union. European Market Surveillance of Pollutant Emissions from Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/191638 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- EU—Draft Commission Implementing Regulation Laying Down Rules, Procedures and Testing Methodologies for the Application of Regulation (EU) 2024/1257 as Regards Exhaust and Evaporative Emission Type-Approval of Vehicles of Categories M1 and N1. Available online: https://www.tuv.com/world/en/vehicle-emissions.html (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Mandatory Periodical Emission Test. Available online: https://www.dekra.com/en/mandatory-periodical-emission-test-b2c/ (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Green NCAP is Evolving: New rules in 2025 to Better Assess the Environmental Performance of Vehicles. Available online: https://www.utac.com/news/green-ncap-is-evolving-new-rules-in-2025-to-better-assess-the-environmental-performance-of-vehicles (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Benchmarking Advanced Low Emission Light-Duty Vehicle Technology. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/vehicle-and-fuel-emissions-testing/benchmarking-advanced-low-emission-light-duty-vehicle-technology (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- EPA-420 Series: Technical Reports on Portable Emission Measurement Systems. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/chapter-I/subchapter-U/part-1065/subpart-J (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- China Published New National Regulation for ICV Road Test. Available online: https://europe.catarctc.com/en/content?id=24 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Iwasa, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Haniu, T. Uncertainty evaluation of a portable emission measurement system (PEMS) during real driving tests. JARI Res. J. 2025, 6, 1–10. Available online: https://img.jari.or.jp/v=1749525241/files/user/pdf/JRJ/JRJ20250601_protection.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Korea Automotive Technology Institute—Leading a Future with Creativity & Innovation. Available online: https://www.katech.re.kr/eng (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- About the National Vehicle and Fuel Emissions Laboratory (NVFEL). Available online: https://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/about-national-vehicle-and-fuel-emissions-laboratory-nvfel (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- EPA Can’t Let “Off-Cycle” Credits Become an Off-Ramp for Automakers. Available online: https://blog.ucs.org/dave-cooke/epa-cant-let-off-cycle-credits-become-an-off-ramp-for-automakers (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Vehicle and Fuel Emissions Testing. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/vehicle-and-fuel-emissions-testing/technical-capabilities-national-vehicle-and-fuel-emissions (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Lee, S.; Fulper, C.; McDonald, J.; Olechiw, M. Real-World Emission Modeling and Validations Using PEMS and GPS Vehicle Data; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2019; 2019-01-0757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Fulper, C.; Cullen, D.; McDonald, J.; Fernandez, A.; Doorlag, M.H.; Sanchez, L.J.; Olechiw, M. On-road portable emission measurement systems test data analysis and light-duty vehicle in-use emissions development. SAE Int. J. Electrified Veh. 2020, 9, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cherry, J.; Safoutin, M.; Neam, A.; McDonald, J.; Newman, K. Modeling and Controls Development of 48 V Mild Hybrid Electric Vehicles; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018; 2018-01-0413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cherry, J.; Safoutin, M.; McDonald, J.; Olechiw, M. Modeling and validation of 48V mild hybrid lithium-ion battery pack. SAE Int. J. Altern. Powertrains 2018, 7, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittelson, D.; Khalek, I.; McDonald, J.; Stevens, J.; Giannelli, R. Particle emissions from mobile sources: Discussion of ultrafine particle emissions and definition. J. Aerosol Sci. 2022, 159, 105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What We Do. Available online: https://www.swri.org/what-we-do (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Southwest Research Institute® an Integral Part of San Antonio’s Aviation Heritage. Available online: https://www.deehoward.org/news/posts/item/southwest-research-institute-an-integral-part-of-san-antonio-s-aviation-heritage (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Light-Duty Cars & Trucks. Available online: https://www.swri.org/markets/automotive-transportation/automotive/emissions/light-duty-cars-trucks (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Chundru, V.; Adsule, K.; Sharp, C. Prediction and Control of Long-Term System Degradation for a Light-Off SCR in an Ultra-Low NOx Aftertreatment System; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2025; 2025-01-8488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chundru, V.; Sharp, C.; Rahman, M.; Balakrishnan, A. System Level Simulation of H2 ICE After Treatment System; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2024; 2024-01-2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.R.; Bhagdikar, P.; Gankov, S.; Sarlashkar, J.V.; Hotz, S. Real-time eco-driving algorithm for connected and automated vehicles using quadratic programming. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Chicago, IL, USA, 19–21 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagdikar, P.; Sarlashkar, J.; Gankov, S.; Rengarajan, S. Demonstration of ego vehicle and system level benefits of eco-driving on chassis dynamometer. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Pract. Mobil. 2024, 6, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Automobile Research Institute. Available online: https://www.jari.or.jp/en/about/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- The Shirosato Test Center. Available online: https://www.jari.or.jp/en/test-courses/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Environment. Available online: https://www.jari.or.jp/en/research-content/environment/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Tutuianu, M.; Bonnel, P.; Ciuffo, B.; Haniu, T.; Ichikawa, N.; Marotta, A.; Pavlovic, J.; Heinz, S. Development of the World-wide harmonized Light duty Test Cycle (WLTC) and a possible pathway for its introduction in the European legislation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2015, 40, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, M.; Ito, T.; Soma, S.; Haniu, T. Study of a real driving emission test using a random cycle generator on a chassis dynamometer. JARI Res. J. 2020, 10, JRJ20201002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniu, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Ito, T. Overview of the development of WLTC and application for the random cycle generator. JARI Res. J. 2022, 10, JRJ20221010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniu, T.; Ito, T.; Soma, S.; Matsuoka, M.; Iihara, K. Research Activities on Real Driving Emission (RDE) Tests in JARI. JARI Res. J. 2022, 12, JRJ20221202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 17507:2021; Road Vehicles—Portable Emission Measuring Systems (PEMS)—Performance Assessment. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/f79f0c51-bc57-40bd-b29d-71d193f9c71a/en-17507-2021 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- China Merchants Testing Vehicle Technology Research Institute. Available online: https://www.cmvr.com.cn/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Service Capabilities. Available online: https://www.cmvr.com.cn/html/fwnl/lgyjcsjd/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- National Quality Inspection Center. Available online: https://www.cmvr.com.cn/html/fwnl/gjzjzx/gjxnyqjz/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Yin, H.; Wang, J.; Hao, C.; Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Hao, L.; Tan, J.; Wang, X.; et al. China 6 moving average window method for real driving emission evaluation: Challenges, causes, and impacts. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, L.; Xu, X.; Qiu, J.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Ge, Y. Impact of shortening Real Driving Emission (RDE) test trips on CO, NOx, and PN10 emissions from different vehicles. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Feng, J.; Xu, X.; Ge, Z.; Lyu, L.; Wang, C.; Ge, Y. Ammonia emissions from series and series-parallel plug-in hybrid electric vehicles under real driving condition. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo. Available online: https://www.ricardo.com/en/who-we-are (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Vehicle Emissions Testing. Available online: https://www.ricardo.com/en/services/transport/emissions-testing (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Ricardo’s Real-World Vehicle Emission Database Reaches a Million Vehicle Measurements. Available online: https://www.ricardo.com/en/news-and-insights/industry-insights/ricardo-s-real-world-vehicle-emission-database-reaches-a-million-vehicle-measurements (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Carslaw, D.C.; Beevers, S.D. Estimations of road vehicle primary NO2 exhaust emission fractions using monitoring data in London. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, S.K.; Farren, N.J.; Vaughan, A.R.; Rose, R.A.; Carslaw, D.C. Strong temperature dependence for light-duty diesel vehicle NOx emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 6587–6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carslaw, D.C.; Farren, N.J.; Vaughan, A.R.; Drysdale, W.S.; Young, S.; Lee, J.D. The diminishing importance of nitrogen dioxide emissions from road vehicle exhaust. Atmos. Environ. X 2019, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovations for Quantum Technology. This is Our Time: Towards the Quantum Age. Available online: https://www.tno.nl/en/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Automotive Campus, Home Meetin. Helmond and Automotive. Available online: https://www.automotivecampus.com/en/about-the-campus/history (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Monitoring Actual Emissions: Report Summary. Real-World Emission Policy & Strategy—Sustainable Mobility. Available online: https://www.tno.nl/en/sustainable/mobility-logistics/monitoring-actual-emissions (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- van Gijlswijk, R.; Ligterink, N.; Bhorasar, A.; Smokers, R. Real-World Fuel Consumption and Electricity Consumption of Passenger Cars and Light Commercial Vehicles—2021. TNO Report 2022, R10409. Available online: https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34639300/erZOUs/TNO-2022-R10409.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Eijk, A.; van Mensch, P.; Elstgeest, M. Tailpipe Emissions of Mopeds in the Dutch fleet. TNO Report 2017, R11495. Available online: https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34625952/CKWYaj/TNO-2017-R11495.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Vermeulen, R.; van Gijlswijk, R.; van Goethem, S. Tail-pipe NOx Emissions of Euro VI Buses in Daily Operation in the Netherlands. TNO Report 2018, R11328. Available online: https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34627250/9C8rot/TNO-2018-R11328.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Vermeulen, R.J. Emissions Testing of a Euro VI LNG-Diesel Dual Fuel Truck in the Netherlands. TNO Report 2019, R10193. Available online: https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34633965/pl7KqC/TNO-2019-R10193.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Vermeulen, R.J.; Ligterink, N.E.; van der Mark, P.J. Real-World Emissions of Non-Road Mobile Machinery. TNO Report 2021, R946931. Available online: https://repository.tno.nl/SingleDoc?find=UID%20a1c81fc2-3ad6-4020-a405-bf8d99830fbe (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- JRC Mission Statement & Work Programme. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-mission-statement-work-programme_en?pk_source=website&pk_medium=link&pk_campaign=hp_mission (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Vehicle Emissions Laboratories. Available online: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/laboratories-z/vehicle-emissions-laboratories_en (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Publications Office of the European Union. Real Driving Emissions Regulation—European Methodology to Fine Tune the EU Real Driving Emissions Data Evaluation Method; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giechaskiel, B.; Valverde, V.; Melas, A.; Clairotte, M.; Bonnel, P.; Dilara, P. Comparison of the Real-Driving Emissions (RDE) of a Gasoline Direct Injection (GDI) vehicle at different routes in Europe. Energies 2024, 17, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publications Office of the European Union. Real Driving Emissions (RDE)—2020 Assessment of Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS) Measurement Uncertainty; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selleri, T.; Melas, A.; Bonnel, P.; Suarez-Bertoa, R. NH3 and CO emissions from fifteen Euro 6d and Euro 6d-TEMP gasoline-fuelled vehicles. Catalysts 2022, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.; Meng, X.; Weiwei, G. Vehicle Emission Solutions for China 6b and Euro 7; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020; 2020-01-0654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Xue, Y.; Thandra, S.; Qi, Q.; Thurston, S.W.; Croft, D.P.; Utel, M.J.; Hopke, P.K.; Rich, D.Q. Source specific fine particles and rates of asthma and COPD healthcare encounters pre-and post-implementation of the Tier 3 vehicle emissions control regulations. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 484, 136737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbier, A.; Salavert, J.M.; Palau, C.E.; Guardiola, C. Analysis of the Euro 7 on-board emissions monitoring concept with real-driving data. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 127, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, J.; Tansini, A.; Suarez, J.; Fontaras, G. Influence of vehicle and battery ageing and driving modes on emissions and efficiency in Plug-in hybrid vehicles. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 24, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornoff, J.; Rodríguez, F. Euro 7: The New Emission Standard for Light-and Heavy-Duty Vehicles in the European Union. International Council on Clean Transportation 2024. Available online: https://theicct.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/ID-116-%E2%80%93-Euro-7-standard_final.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Kozyra, J.; Łukasik, Z.; Kuśmińska-Fijałkowska, A.; Folęga, P.; Janota, A. Standards and requirements concerning reduction of CO2 emission for new passenger cars. Arch. Transp. 2025, 74, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, A.; Mądziel, M.; Kuszewski, H.; Lejda, K.; Balawender, K.; Jaremcio, M.; Jakubowski, M.; Wojewoda, P.; Lew, K.; Ustrzycki, A. Analysis of Cold Start Emission from Light Duty Vehicles Fueled with Gasoline and LPG for Selected Ambient Temperatures; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020; 2020-01-2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, A.; Mądziel, M.; Kuszewski, H.; Lejda, K.; Balawender, K.; Jaremcio, M.; Jakubowski, M.; Woś, P.; Lew, K. The Impact of Driving Resistances on the Emission of Exhaust Pollutants from Vehicles with the Spark Ignition Engine Fuelled by Petrol and LPG; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020; 2020-01-2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mądziel, M. Instantaneous CO2 emission modelling for a Euro 6 start-stop vehicle based on portable emission measurement system data and artificial intelligence methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 6944–6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mądziel, M. Modelling CO2 emissions from vehicles fuelled with compressed natural gas based on on-road and chassis dynamometer tests. Energies 2024, 17, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mądziel, M. Quantifying emissions in vehicles equipped with energy-saving start–stop technology: THC and NOx modeling Insights. Energies 2024, 17, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, A.; Mądziel, M.; Lew, K.; Campisi, T.; Woś, P.; Kuszewski, H.; Wojewoda, P.; Ustrzycki, A.; Balawender, K.; Jakubowski, M. Evaluation of the effect of chassis dynamometer load setting on CO2 emissions and energy demand of a full hybrid vehicle. Energies 2022, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mądziel, M. State of charge prediction for Li-Ion batteries in EVs for traffic microsimulation. Energies 2025, 18, 4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkisz, J.; Merkisz-Guranowska, A.; Pielecha, J.; Fuć, P.; Jacyna, M. On-road exhaust emissions of passenger cars using Portable Emission Measurement System (PEMS). In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on Architecture and Civil Engineering (ACE 2013), Singapore, 18–19 March 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkisz, J.; Pielecha, J.; Bielaczyc, P.; Woodburn, J. Analysis of Emission Factors in RDE Tests as Well as in NEDC and WLTC Chassis Dynamometer Tests; SAE Technical Papers; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2016; 2016-01-0980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkisz, J.; Pielecha, J. Real driving emissions—Vehicle tests in variable terrain. J. KONES—Powertrain Transp. 2015, 22, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

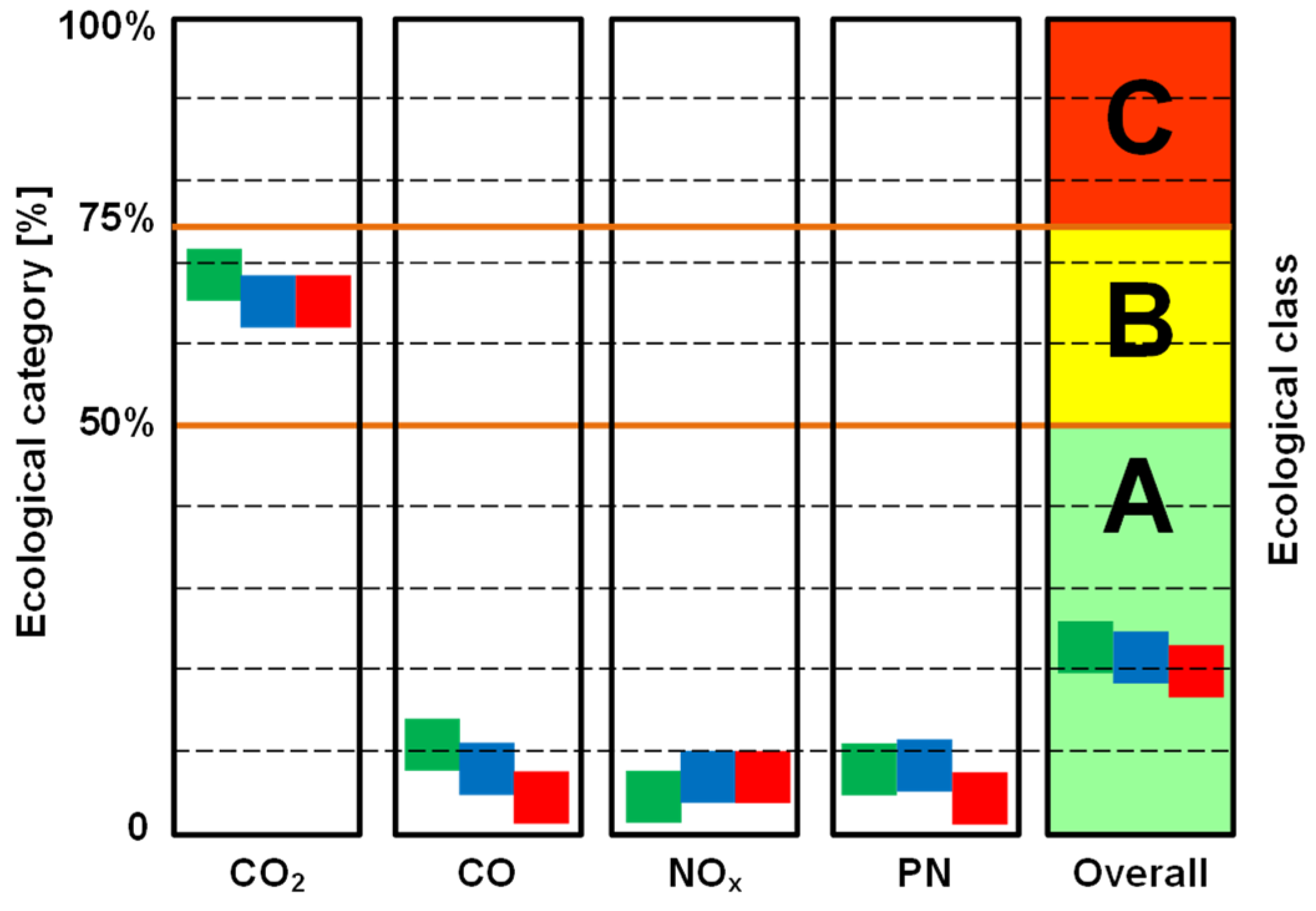

- Skobiej, K.; Pielecha, J. Plug-in hybrid ecological category in real driving emissions. Energies 2021, 14, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkisz, J.; Pielecha, J.; Gis, W. Gasoline and LPG Vehicle Emission Factors in a Road Test; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2009; 2009-01-0937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielecha, J.; Merkisz, J.; Markowski, J.; Gis, W. On-Board Emissions Measurement from Gasoline, Diesel and CNG Fuelled Vehicles; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2010; 2010-01-1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gis, W.; Merkisz, J. The development status of electric (BEV) and hydrogen (FCEV) passenger cars park in the world and new research possibilities of these cars in real traffic conditions. Combust. Engines 2019, 178, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gis, W.; Gis, M.; Wiśniowski, P.; Taubert, S. Initial assessment of the legitimacy of limiting the maximum permissible speed on highways and motorways based on tests in real traffic conditions. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 642, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielecha, J.; Skobiej, K.; Gis, M.; Gis, W. Particle number emission from vehicles of various drives in the RDE tests. Energies 2022, 15, 6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Standard | Region | Date | Test Type | NOx [g/km] | PM [g/km] | CO [g/km] | Fuel Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Euro 6d-Temp | Europe | 2020 | WLTC/RDE | 0.06/0.168 * | 0.005 | 1.0 | Gasoline | RDE with CF = 2.1 |

| Euro 6d-Temp | Europe | 2020 | WLTC/RDE | 0.08/0.168 * | 0.005 | 0.50 | Diesel | RDE with CF = 2.1 |

| Euro 7 | Europe | 2026 | WLTC/RDE | 0.06/0.086 ** | 0.0045 | 1.0 | Gasoline | PN limit reduced to 10 nm |

| Euro 7 | Europe | 2026 | WLTC/RDE | 0.08/0.114 ** | 0.0045 | 0.50 | Diesel | Non-exhaust emissions included |

| China 6b | China | 2023 | WLTP/RDE | 0.035/0.0735 * | 0.003 | 0.5 | Gasoline and Diesel | RDE with CF = 2.1 |

| EPA Tier 3 | North America | 2025 | FTP cycle | ~0.019 (fleet avg.) | ~0.0019 | 1.7 | Gasoline | NMOG + NOx combined; phased through 2025 |

| CARB LEV III | California | 2025 | FTP/SFTP | ~0.034 (ULEV) | 0.0019 | 0.6–4.2 | Gasoline | Stricter than federal EPA; technology driver |

| Japan (JC08) | Japan | 2015 | JC08 cycle | 0.08 | 0.005 | 1.15 | Gasoline | RDE procedures under development |

| Type of Engine | Exhaust Compounds | R2 | Possibility of Determining Emissions in the RDE Test Based on |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gasoline | CO2 | 0.855 | WLTCRDE |

| CO | 0.936 | WLTCRDE | |

| NOx | – | – | |

| PN | 0.480 | WLTCRDE | |

| Diesel | CO2 | 0.853 | WLTC1+2 |

| CO | 0.939 | WLTC1+2 | |

| NOx | 0.963 | WLTC1+2 | |

| PN | 0.982 | WLTCRDE | |

| Hybrid | CO2 | 0.923 | WLTCRDE |

| CO | 0.980 | WLTCRDE | |

| NOx | 0.767 | WLTC1+2 | |

| PN | 0.999 | WLTCRDE |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pielecha, J.; Woś, P.; Kuszewski, H.; Mądziel, M.; Krzemiński, A.; Kulasa, P.; Gis, W.; Piątkowski, P.; Sobczak, J. Real-Driving Emissions of Euro 2–Euro 6 Vehicles in Poland—17 Years of Experience. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010348

Pielecha J, Woś P, Kuszewski H, Mądziel M, Krzemiński A, Kulasa P, Gis W, Piątkowski P, Sobczak J. Real-Driving Emissions of Euro 2–Euro 6 Vehicles in Poland—17 Years of Experience. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010348

Chicago/Turabian StylePielecha, Jacek, Paweł Woś, Hubert Kuszewski, Maksymilian Mądziel, Artur Krzemiński, Paulina Kulasa, Wojciech Gis, Piotr Piątkowski, and Jakub Sobczak. 2026. "Real-Driving Emissions of Euro 2–Euro 6 Vehicles in Poland—17 Years of Experience" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010348

APA StylePielecha, J., Woś, P., Kuszewski, H., Mądziel, M., Krzemiński, A., Kulasa, P., Gis, W., Piątkowski, P., & Sobczak, J. (2026). Real-Driving Emissions of Euro 2–Euro 6 Vehicles in Poland—17 Years of Experience. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010348