Analysis of Pore Structure Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Shale Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Qing-1 Member in Gulong Sag, Songliao Basin, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

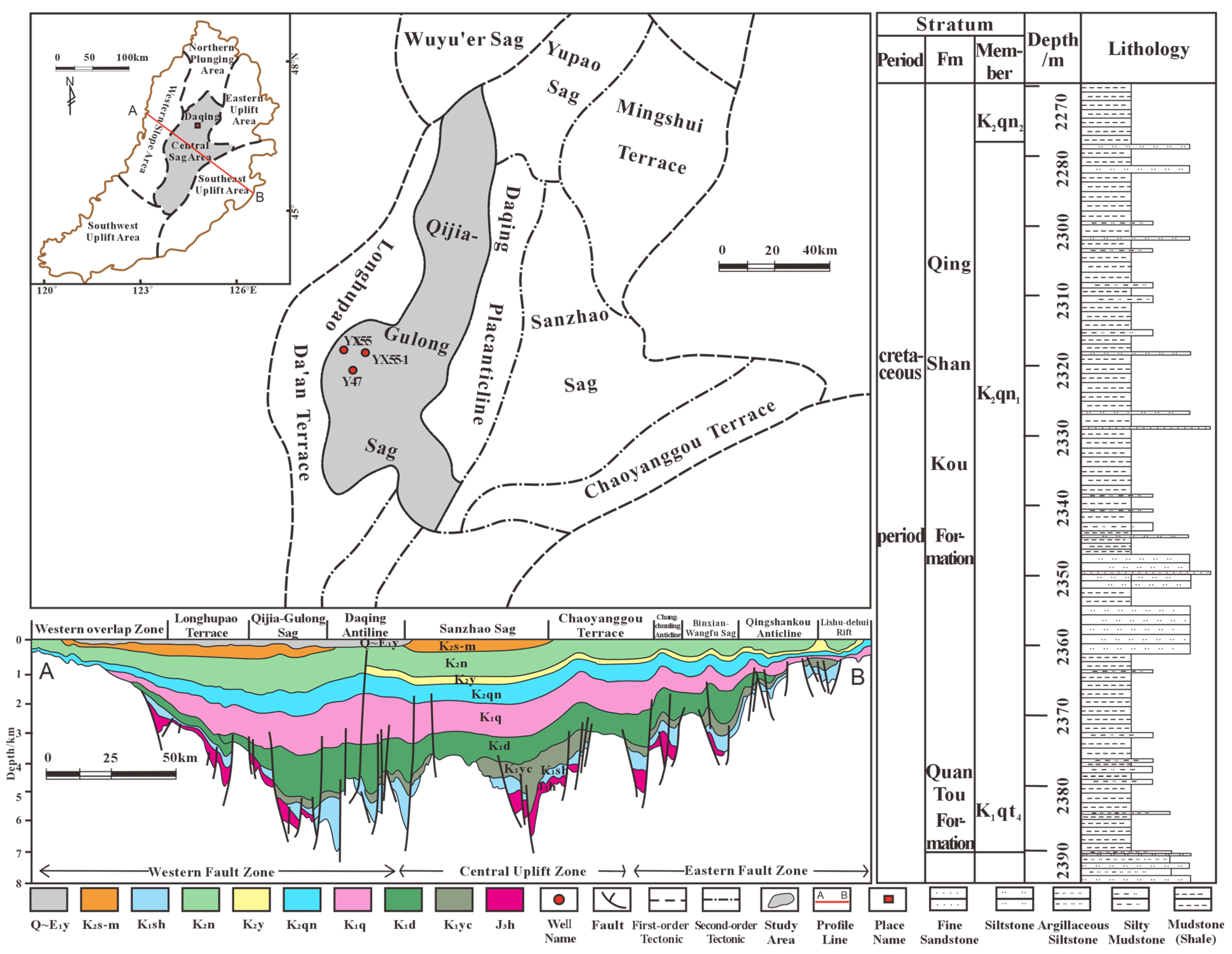

2. Regional Geological Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Samples

3.2. Experimental Methods

4. Results

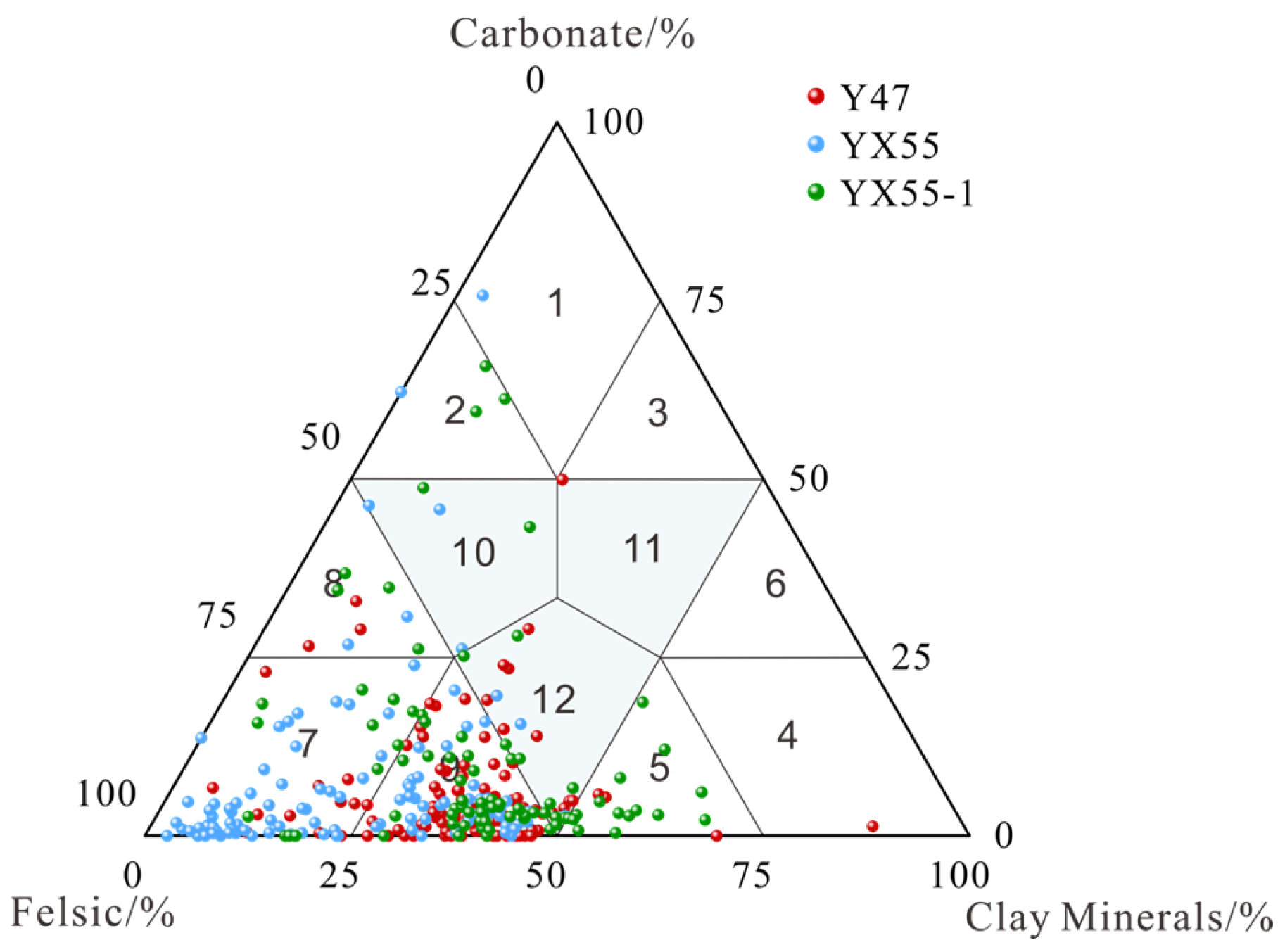

4.1. Lithofacies Classification

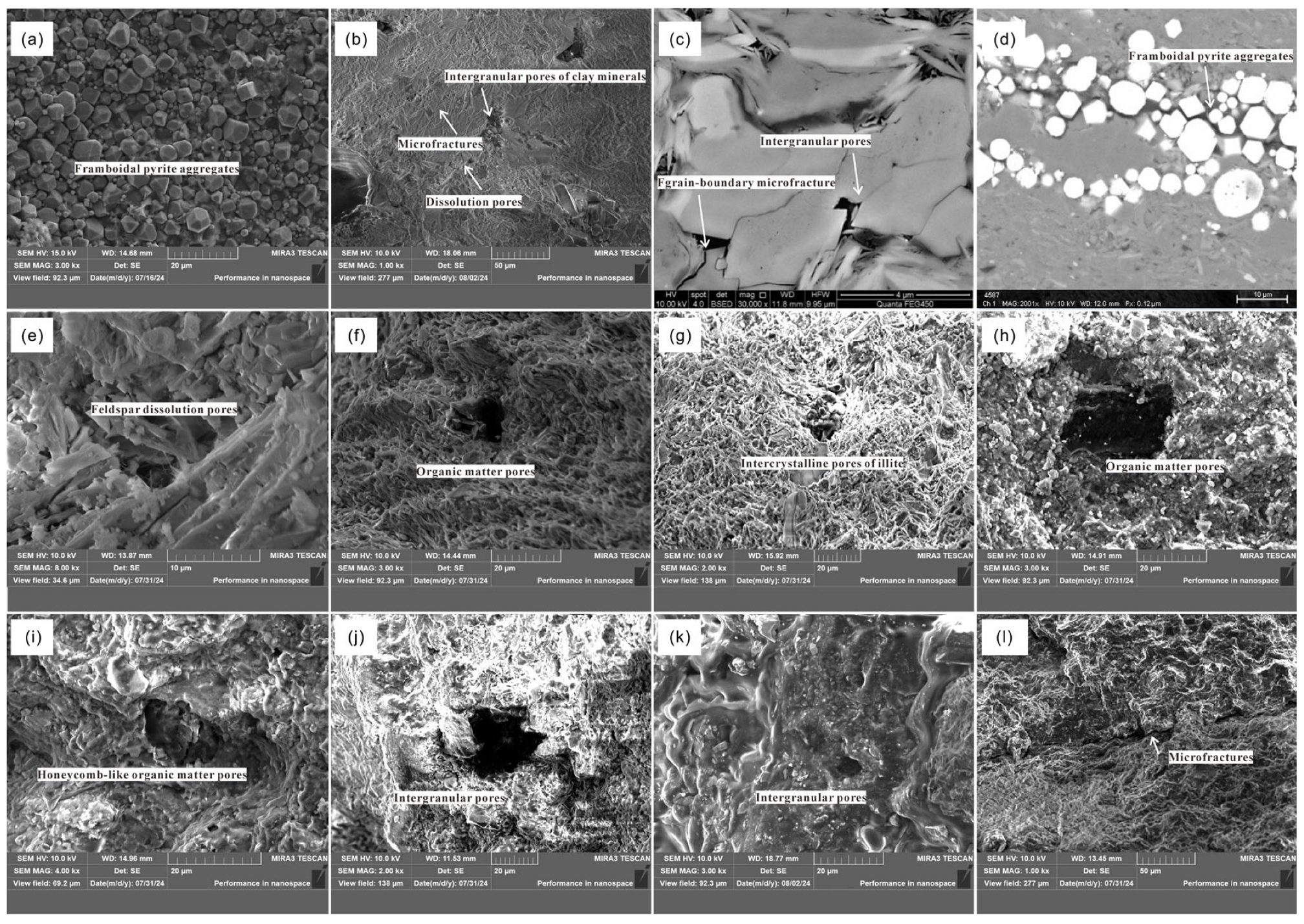

4.2. Reservoir Space Types

4.3. Multi-Scale Characteristics of Pore Structure

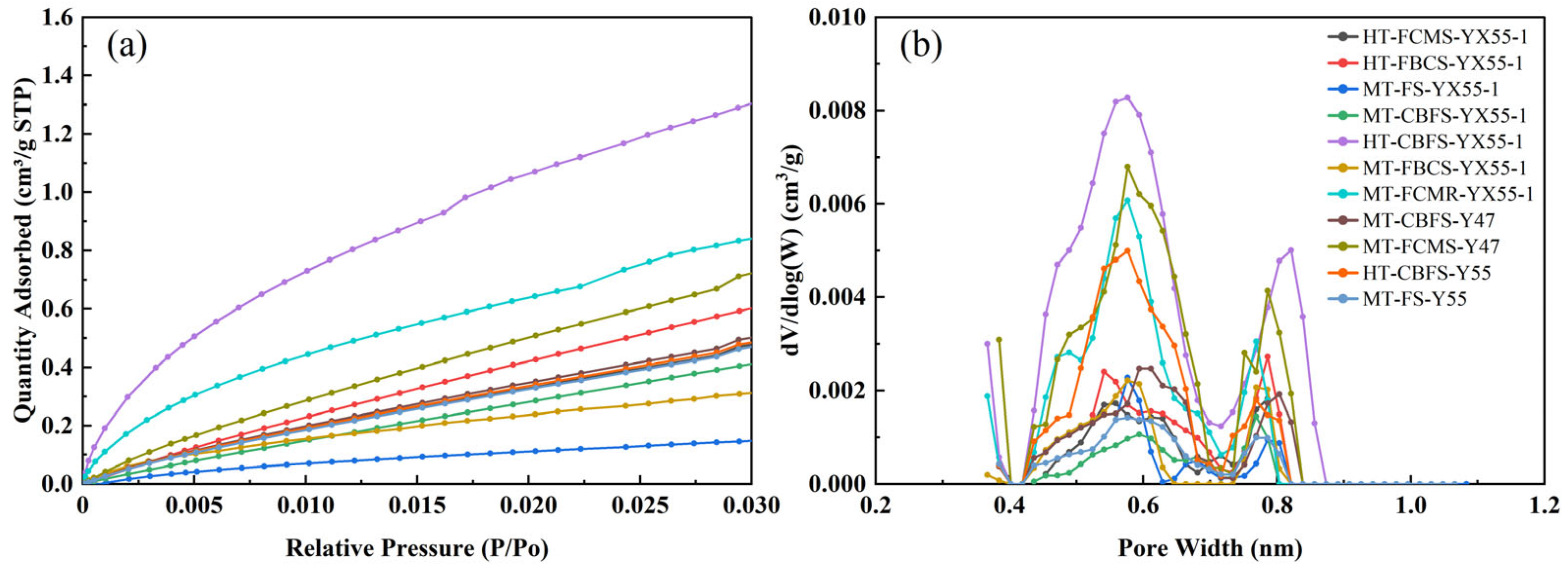

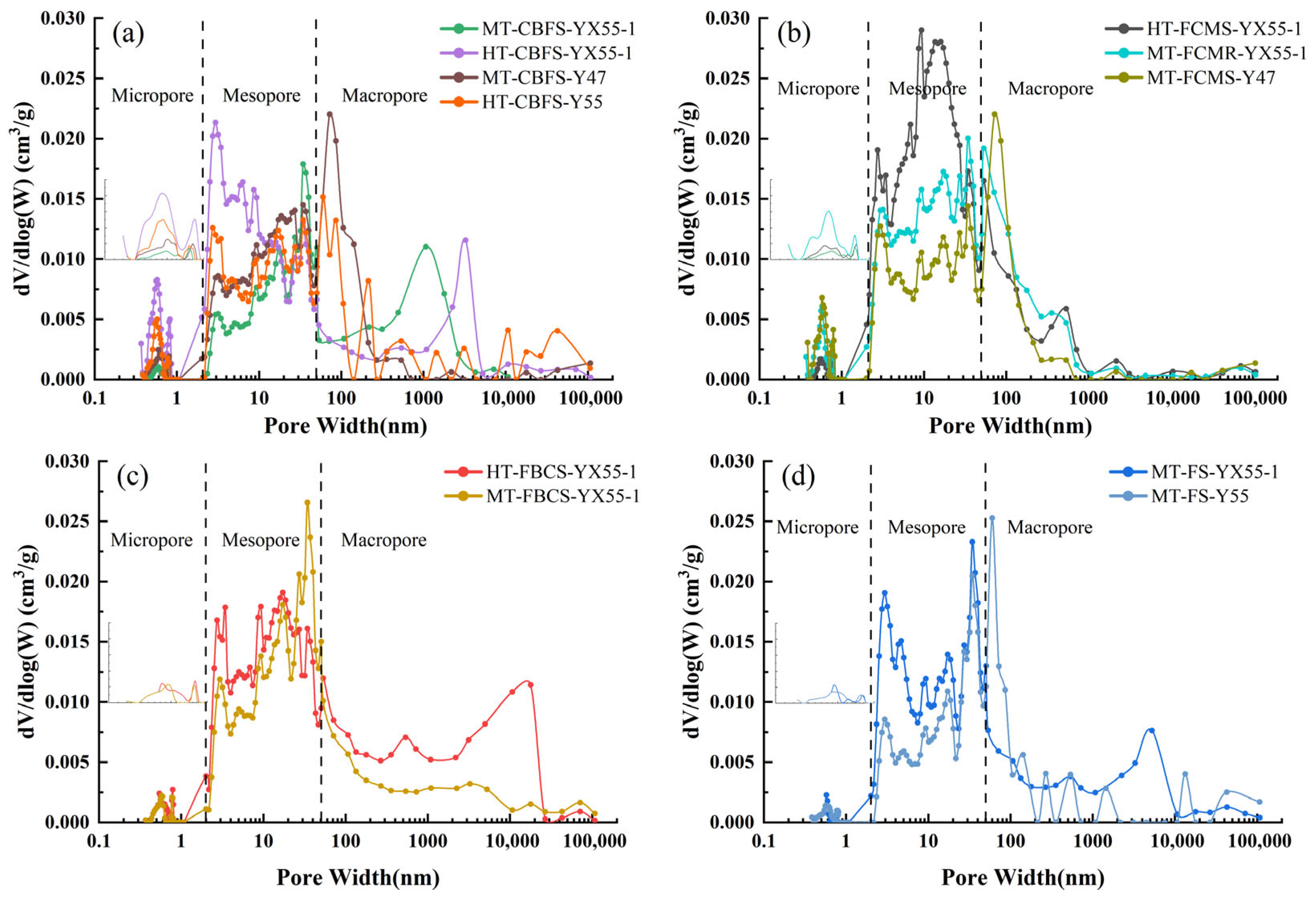

4.3.1. Gas Adsorption

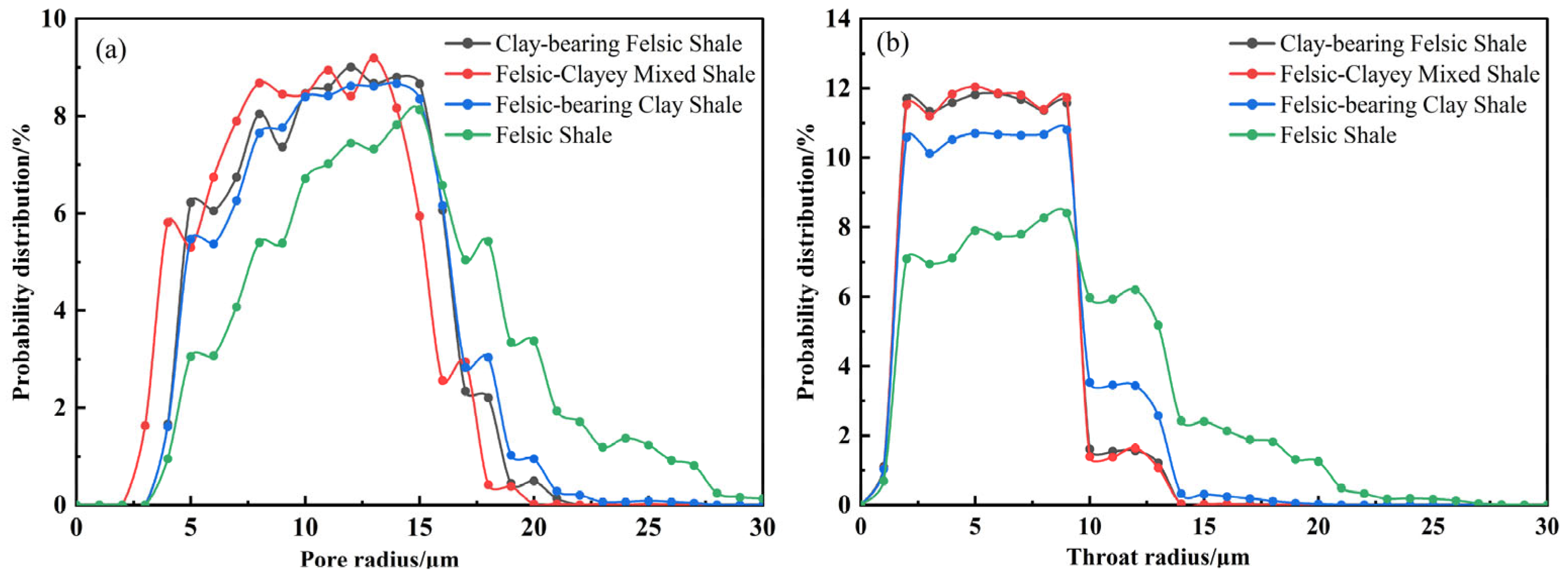

4.3.2. High-Pressure Mercury Intrusion

4.3.3. 3D Connectivity Characteristics by CT Scanning

4.3.4. Joint Characterization of Pore Size Distribution

5. Discussion on Experimental Results

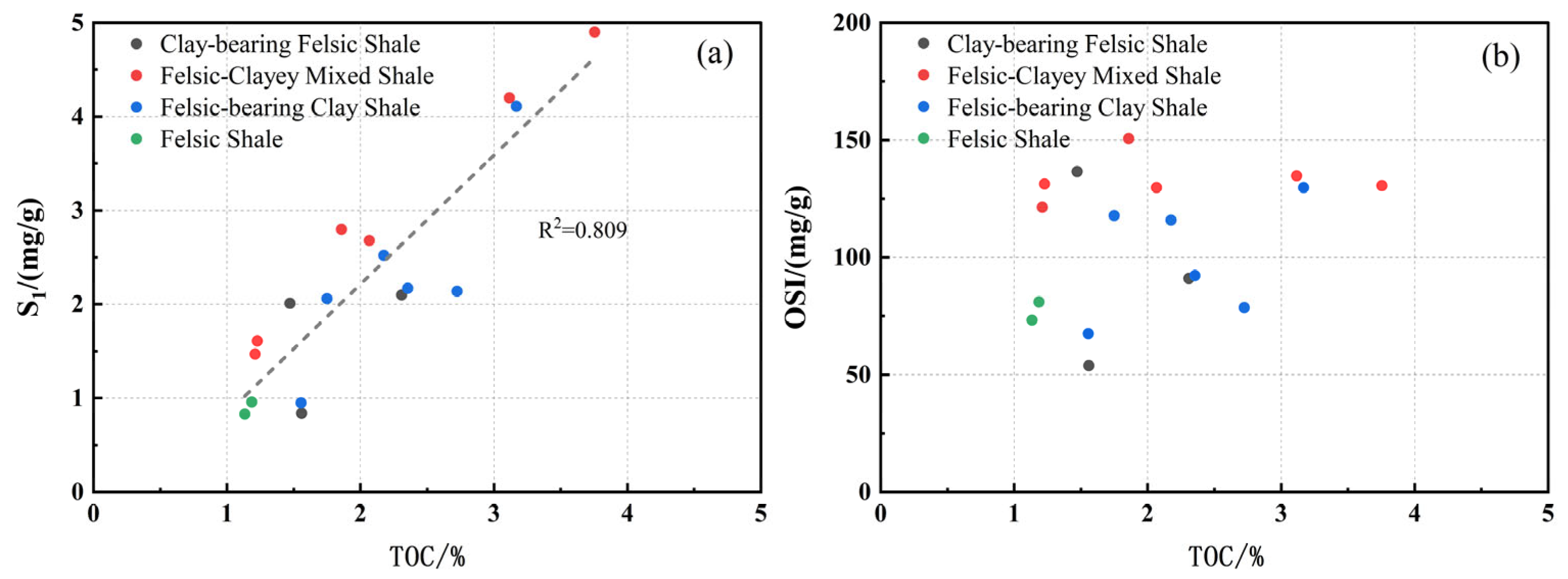

5.1. Oil-Bearing Property and Identification of Dominant Lithofacies

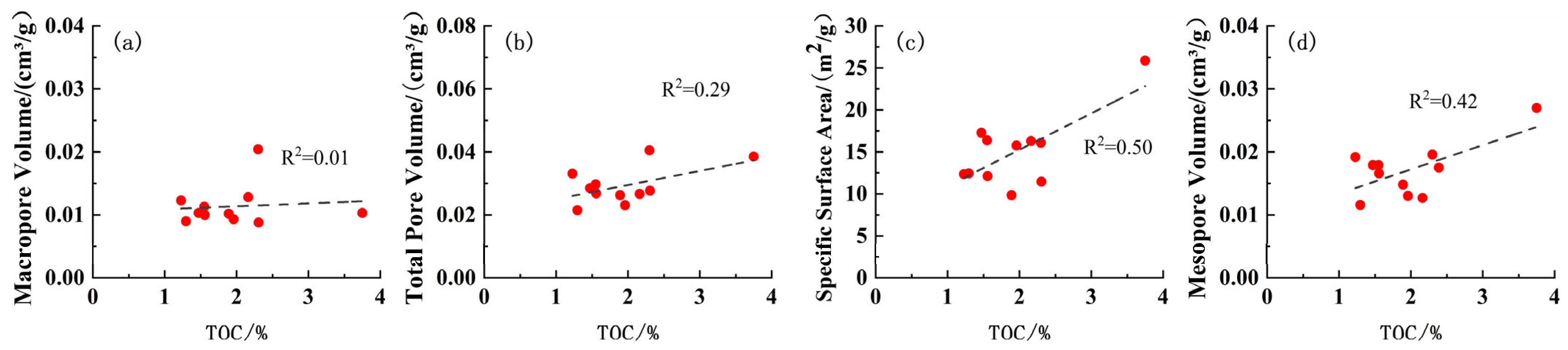

5.2. Influence of TOC on Pore Development

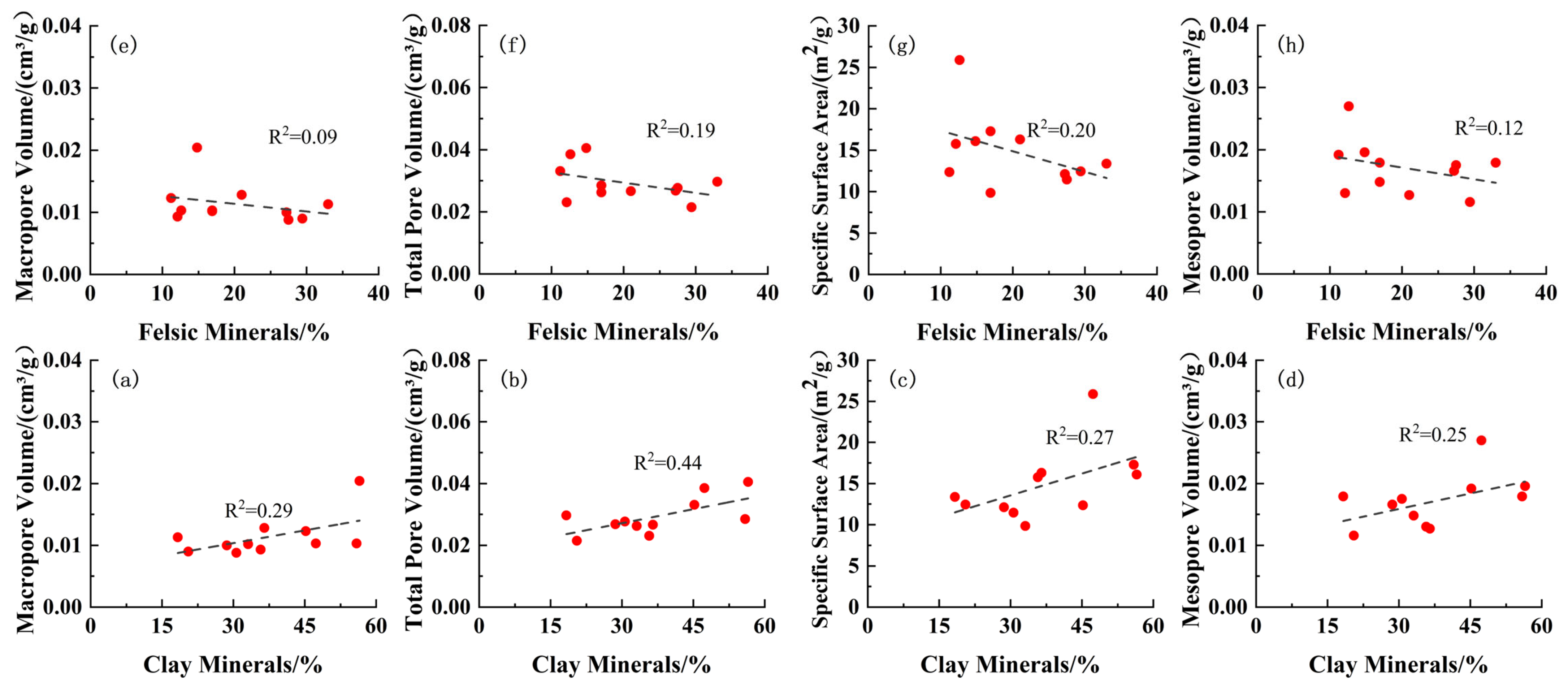

5.3. Influence of Mineral Composition on Pore Development

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zou, C.N.; Yang, Z.; Cui, J.W.; Zhu, R.K.; Hou, L.H.; Tao, S.Z.; Yuan, X.J.; Wu, S.T.; Lin, H.S..; Wang, L.; et al. Formation Mechanism, Geological Characteristics and Development Strategy of Nonmarine Shale Oil in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2013, 40, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Luo, Q.; Liu, D.; Gao, Z. Progress and development trend of unconventional oil and gas geological research. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2017, 44, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangzheng, J. Re-recognition of “unconventional” in unconventional oil and gas. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Fei, L.; Wei, C.; Yang, Y.; Tang, W.; Xiao, D.; Qian, Y. Microscopic occurrence and self-containment mechanism of continental shale oil: Case study of Lucaogou Formation in Jimusaer sag, Junggar Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2025, 46, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.F.; Lu, J.M.L. Hydrocarbon accumulation patterns and exploration potential of whole petroleum systems in northern Songliao Basin. Pet. Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing 2024, 43, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Baowen, C.U.I.; Zihui, F.; Hongmei, S.H.A.O.; Qiuli, H.U.O.; Bo, G.A.O.; Huasen, Z.E.N.G. In-situ hydrocarbon formation and accumulation mechanisms of micro-and nano-scale pore-fracture in Gulong shale, Songliao Basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, Y. Enrichment conditions and favorable zones for exploration and development of continental shale oil in Songliao Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2023, 44, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, M.; Liu, S.; Hao, Y. Pore characteristics and influencing factors of different types of shales. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 102, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S.; Wirth, R.; Schreiber, A.; Schulz, H.M.; Horsfield, B. Formation of nanoporous pyrobitumen residues during maturation of the Barnett shale (Fort Worth Basin). Int. J. Coal Geol. 2012, 103, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, F.; Bai, T.A.; Han, B.; Lu, Y.; Gao, H. Shale oil occurrence mechanisms: A comprehensive review of the occurrence state, occurrence space, and movability of shale oil. Energies 2022, 15, 9485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, C.; Mei, X.; Qiao, L.J.Y. Status and prospect of research on microscopic shale gas reservoir space. Oil Gas Geol. 2015, 36, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, G.; Wu, H.; Feng, Z.; Tian, H.; Xie, Y.; Wu, H. Lithofacies Characteristics of Gulong Shale and Its Influence on Reservoir Physical Properties. Energies 2024, 17, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Oyediran, I.A.; Huang, R.; Hu, F.; Du, T.; Hu, R.; Li, X. Study on pore structure characteristics of marine and continental shale in China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Feng, Z.; Shao, H.; Zeng, H.; Gao, B.; Jiang, H. Formation mechanisms of nano-scale pores/fissures and shale oil enrichment characteristics for Gulong shale, Songliao Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2023, 44, 1350–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Meng, Q.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, L.; et al. Millimeter-scale fine evaluation and significance of shale reservoir performance and oil-bearing property: A case study of Member 1 of Qingshankou Formation in Songliao Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2024, 45, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmann, A.; Mastalerz, M.; Schimmelmann, A.; Pedersen, P.K.; Bish, D. Relationships between porosity, organic matter, and mineral matter in mature organic-rich marine mudstones of the Belle Fourche and Second White Specks formations in Alberta, Canada. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2014, 54, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Shi, J.; Fu, X.; Lü, Y.; Sun, X.; Gong, L.; Bai, Y. Petrological characteristics and shale oil enrichment of lacustrine fine-grained sedimentary system: A case study of organic-rich shale in first member of Cretaceous Qingshankou Formation in Gulong Sag, Songliao Basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.J.K.; Bustin, R.M. The importance of shale composition and pore structure upon gas storage potential of shale gas reservoirs. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2009, 26, 916–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, J.F.; Laubach, S.E.; Olson, J.E.; Eichhubl, P.; Fall, A. Natural Fractures in shale: A review and new observations. AAPG Bull. 2014, 98, 2165–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Shengxin, L.I.U.; Yinsheng, M.A.; Chengming, Y.I.N.; Chenglin, L.I.U.; Zongxing, L.I.; Yong, L.I. Macro-fracture mode and micro-fracture mechanism of shale. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2015, 42, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, T.; Cai, Y.; Feng, Z.; Bai, B.; Jiang, H.; Wang, B. Advances and trends of non-marine shale sedimentology: A case study from Gulong Shale of Daqing Oilfield, Songliao Basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1183–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Jia, C.; Zhang, J.; Cui, B.; Bai, J.; Huo, Q.; Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Zeng, H.; Liu, W. Resource potential of Gulong shale oil in the key areas of Songliao Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2024, 45, 1699–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fu, L. Impact of pore structure on imbibition characteristics in Qingshankou Formation shale oil reservoirs, Songliao Basin. Spec. Oil Gas Reserv. 2025, 32, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xiao, F.; Li, S.; Yang, J.; Huang, Y.; Ye, C. Enrichment model of tight shale oil in the first Member of Cretaceous Qingshankou Formation in the southern Qijia sag, Songliao Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2024, 98, 3393–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Lin, T.; Li, J.; Fu, X.; Cui, K.; Gao, B.; Bai, Y.; Fu, X. Coupling mechanism of Gulong shale oil enrichment in Songliao Basin. Pet. Geol. Oilfield Dev. Daqing 2024, 43, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Meng, Q.; Fu, X.; Lin, T.; Bai, Y.; Tian, S.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Z. Composition of generated and expelled hydrocarbons and phase evolution of shale oil in the 1st member of Qingshankou Formation, Songliao Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2024, 45, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Jiang, Z. Shale lithofacies and reservoir space of the Wufeng–Longmaxi formation, Sichuan Basin, China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2012, 39, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiong, J.; Liang, L. Investigation of pore structure and fractal characteristics of organic-rich Yanchang formation shale in central China by nitrogen adsorption/desorption analysis. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 22, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Abid, A.; Lü, M. Quantitative analysis of nitrogen adsorption hysteresis loop and its indicative significance to pore structure characterization: A case study on the Upper Triassic Chang 7 Member, Ordos Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2023, 44, 495–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shen, Y.; He, S. Quantitative pore characterization and the relationship between pore distributions and organic matter in shale based on Nano-CT image analysis: A case study for a lacustrine shale reservoir in the Triassic Chang 7 member, Ordos Basin, China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 27, 1630–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Hu, W.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Lu, D.; Liu, G. Pore throat structure characteristics of tight sandstone reservoirs and their influence on movable fluid occurrence: Taking the Chang-7 Member of Qingcheng area of Ordos Basin as an example. Bull. Geol. Sci. Technol. 2024, 43, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Niu, D.; Luan, Z.; Dang, H.; Pan, X.; Sun, P. Kinetic characteristics of secondary hydrocarbon generation from oil shale and coal at different maturation stages: Insights from open-system pyrolysis. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2025, 308, 104845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Yu, Z.; Huang, W. Reservoir space and controlling factors of lacustrine laminated shale oil reservoir: A case study of Cretaceous Qingshankou Formation in the Changling Sag, southern Songliao Basin, NE China. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2024, 35, 1671–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Fan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Z. Differential impact of clay minerals and organic matter on pore structure and its fractal characteristics of marine and continental shales in China. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 216, 106334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Well Name | Abbrevia tion | Well Depth | TOC /% | Felsic /% | Clay /% | Cabon-ate/% | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Pore Volume Proportion (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mp | Ms | Mc | Total | Mp | Ms | Mc | |||||||

| YX55-1 | HT-CBFS | 2378.91 m | 2.3074 | 61.5 | 30.6 | 2.9 | 0.0014 | 0.0175 | 0.0088 | 0.0277 | 5.05 | 63.18 | 31.77 |

| YX55-1 | MT-CBFS | 2368.10 m | 1.5582 | 67.3 | 28.6 | 2.7 | 0.0001 | 0.0166 | 0.01 | 0.0268 | 0.37 | 62.17 | 37.45 |

| YX55-1 | HT-FCMS | 2357.40 m | 3.75 | 48.2 | 47.3 | 1.8 | 0.0012 | 0.027 | 0.0103 | 0.0385 | 3.12 | 70.13 | 26.75 |

| YX55-1 | MT-FCMS | 2382.06 m | 1.2265 | 47.2 | 45.2 | 3.6 | 0.0015 | 0.0192 | 0.0123 | 0.0331 | 4.55 | 58.18 | 37.27 |

| YX55-1 | HT-FBCS | 2359.47 m | 2.3 | 37.7 | 56.5 | 3.4 | 0.0004 | 0.0196 | 0.0204 | 0.0405 | 0.99 | 48.51 | 50.50 |

| YX55-1 | MT-FBCS | 2312.46 m | 1.55 | 38.62 | 55.88 | 3.48 | 0.0006 | 0.0179 | 0.0103 | 0.0285 | 2.08 | 62.15 | 35.76 |

| YX55-1 | MT-FS | 2328.42 m | 1.4716 | 81.7 | 18.3 | 0 | 0.0006 | 0.0179 | 0.0113 | 0.0297 | 2.01 | 60.07 | 37.92 |

| Y47 | MT-CBFS | 2351.67 m | 1.89 | 55.1 | 33.1 | 9.4 | 0.0013 | 0.0148 | 0.0102 | 0.0263 | 4.80 | 56.36 | 38.84 |

| Y47 | MT-FCMS | 2374.06 m | 1.96 | 48.5 | 35.7 | 14.6 | 0.0008 | 0.013 | 0.0093 | 0.0231 | 3.38 | 56.33 | 40.29 |

| Y55 | HT-CBFS | 2388.28 m | 2.16 | 53.3 | 36.5 | 4.6 | 0.0012 | 0.0127 | 0.0128 | 0.0267 | 4.46 | 47.58 | 47.96 |

| Y55 | MT-FS | 2376.32 m | 1.2963 | 60.3 | 20.5 | 16.7 | 0.0009 | 0.0116 | 0.009 | 0.0215 | 4.19 | 53.95 | 41.86 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Lei, Z.; Hu, W.; Shi, H.; Wu, W. Analysis of Pore Structure Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Shale Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Qing-1 Member in Gulong Sag, Songliao Basin, China. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010343

Li S, Lei Z, Hu W, Shi H, Wu W. Analysis of Pore Structure Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Shale Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Qing-1 Member in Gulong Sag, Songliao Basin, China. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010343

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shanshan, Zhongying Lei, Wangshui Hu, Huanshan Shi, and Wangfa Wu. 2026. "Analysis of Pore Structure Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Shale Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Qing-1 Member in Gulong Sag, Songliao Basin, China" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010343

APA StyleLi, S., Lei, Z., Hu, W., Shi, H., & Wu, W. (2026). Analysis of Pore Structure Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Shale Reservoirs: A Case Study of the Qing-1 Member in Gulong Sag, Songliao Basin, China. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010343