Influence of Personality Traits on Pain Perception, Attitude, Satisfaction, Compliance, and Quality of Life in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration and Protocol

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Screening and Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis

2.7. Quality Assessment

2.8. Certainty of Evidence Assessment

3. Results

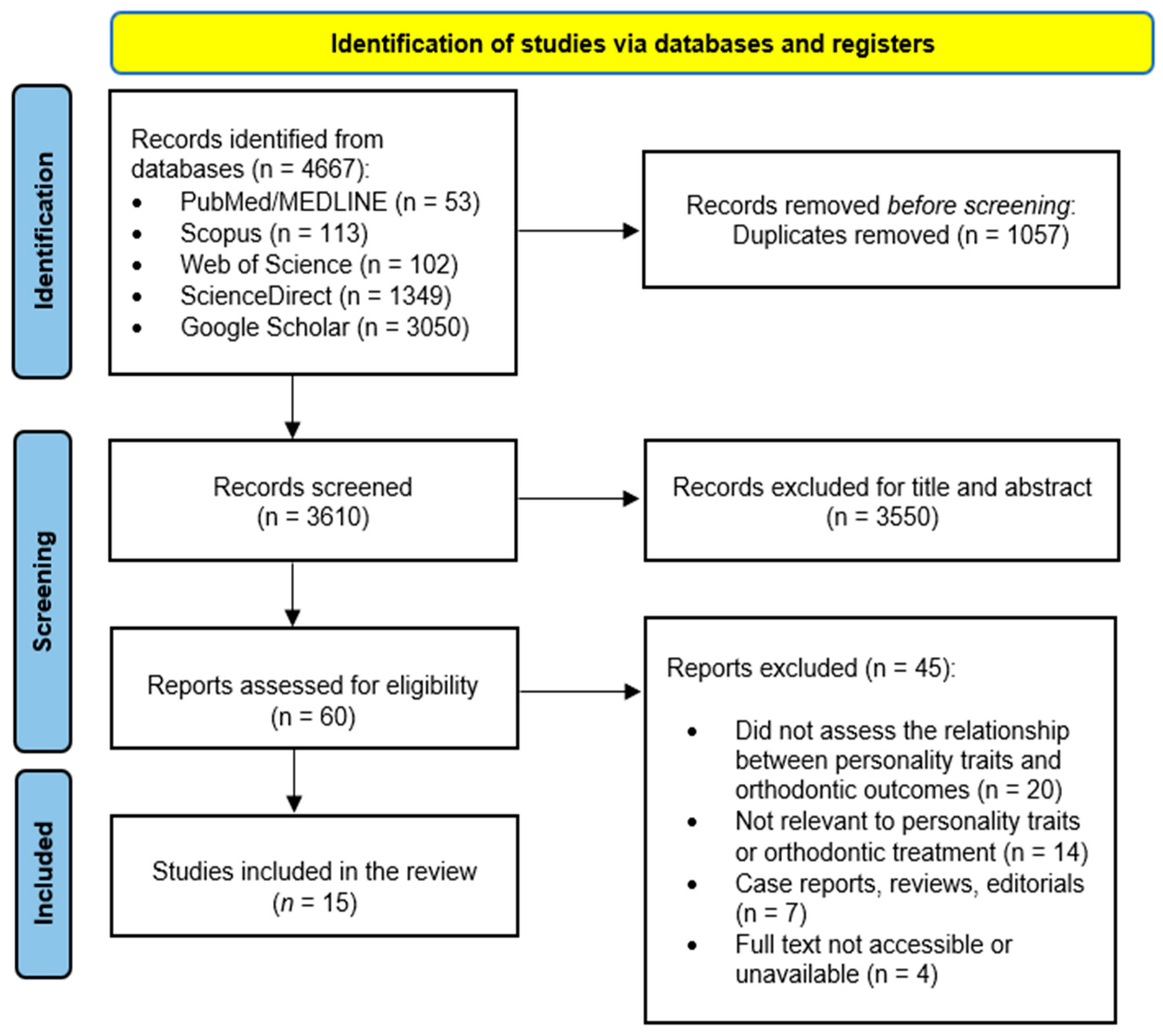

3.1. Articles Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics and Participant Details

3.3. Summary Findings

3.4. Studies Included

3.5. Quality Evaluation

3.6. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Personality and Attitudes Toward Orthodontic Treatment

4.2. Personality and Satisfaction

4.3. Personality and Compliance

4.4. Personality and Pain Perception

4.5. Personality and OHRQoL

4.6. Gender Effects

4.7. Clinical Implications

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nayak, U.A.; Winnier, J.; S, R. The Relationship of Dental Aesthetic Index with Dental Appearance, Smile and Desire for Orthodontic Correction. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2009, 2, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, C.F.; Drummond, A.F.; Lages, E.M.B.; Pretti, H.; Ferreira, E.F.; Abreu, M.H.N.G. The Dental Aesthetic Index and Dental Health Component of the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need as Tools in Epidemiological Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3277–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicita, F.; D’Amico, C.; Filardi, V.; Spadaro, D.; Aquilio, E.; Mancini, M.; Fiorillo, L. Chemical-Physical Characterization of PET-G-Based Material for Orthodontic Use: Preliminary Evaluation of Micro-Raman Analysis. Eur. J. Dent. 2024, 18, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicita, F.; Salmeri, F.; Runci Anastasi, M.; Aquilio, E.; Lipari, F.; Centofanti, A.; Favaloro, A. Morphological and Three-Dimensional Analysis for the Clinical Reproduction of Orthodontic Attachments: A Preliminary Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi Bayat, J.; Huggare, J.; Mohlin, B.; Akrami, N. Determinants of Orthodontic Treatment Need and Demand: A Cross-Sectional Path Model Study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2017, 39, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Berlin-Broner, Y.; Levin, L. Improving Patient Well-Being as a Broader Perspective in Dentistry. Int. Dent. J. 2023, 73, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felemban, O.M.; Alharabi, N.T.; A Alamoudi, R.A.; Alturki, G.A.; Helal, N.M. Factors Influencing the Desire for Orthodontic Treatment among Patients and Parents in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Orthod. Sci. 2022, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Abutayyem, H.; Kanwal, B.; AL Shayeb, M. Future of Orthodontics-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Emerging Trends in This Field. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicita, F.; D’Amico, C.; Minervini, G.; Cervino, G.; Fiorillo, L. Toothpaste Consumption: Implications for Health and Sustainability in Oral Care. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2023, 12, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicita, F.; Calapaj, M.; Alibrandi, S.; Donato, L.; Aquilio, E.; D’Angelo, R.; Sidoti, A. Efficacy of an Experimental Gaseous Ozone-Based Sterilization Method for Clear Aligners. Angle Orthod. 2024, 94, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sischo, L.; Broder, H.L. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life: What, Why, How, and Future Implications. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Närhi, L.; Mattila, M.; Tolvanen, M.; Pirttiniemi, P.; Silvola, A.-S. The Associations of Dental Aesthetics, Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Satisfaction with Aesthetics in an Adult Population. Eur. J. Orthod. 2023, 45, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feu, D.; de Oliveira, B.H.; de Oliveira Almeida, M.A.; Kiyak, H.A.; Miguel, J.A.M. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Orthodontic Treatment Seeking. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 138, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusanen, J.; Lahti, S.; Tolvanen, M.; Pirttiniemi, P. Quality of Life in Patients with Severe Malocclusion before Treatment. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvola, A.-S.; Rusanen, J.; Tolvanen, M.; Pirttiniemi, P.; Lahti, S. Occlusal Characteristics and Quality of Life before and after Treatment of Severe Malocclusion. Eur. J. Orthod. 2012, 34, 704–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; McGrath, C.; Hägg, U. The Impact of Malocclusion/Orthodontic Treatment Need on the Quality of Life. A Systematic Review. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicita, A.; Fumia, A.; Caparello, C.; Meduri, C.F.; Filippello, P.; Sorrenti, L. Goal Achievement and Academic Dropout Among Italian University Students: The Mediating Role of Academic Burnout. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Roige, S.; Gray, J.C.; MacKillop, J.; Chen, C.-H.; Palmer, A.A. The Genetics of Human Personality. Genes. Brain. Behav. 2018, 17, e12439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.W. Back to the Future: Personality and Assessment and Personality Development. J. Res. Pers. 2009, 43, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Volume 1—Personality Theories and Models; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fajkowska, M.; Kreitler, S. Status of the Trait Concept in Contemporary Personality Psychology: Are the Old Questions Still the Burning Questions? J. Pers. 2018, 86, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, A.; Vernon, P.A. Looking beyond the Big Five: A Selective Review of Alternatives to the Big Five Model of Personality. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 169, 110002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.M.; Caspi, A.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E.; Broadbent, J.M. Personality and Oral Health. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 119, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrukh, M.; Khan, A.A.; Shahid Khan, M.; Ravan Ramzani, S.; Soladoye, B.S.A. Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of Family Factors, Personality Traits and Self-Efficacy. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 13, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Othman, R.; El Othman, R.; Hallit, R.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Personality Traits, Emotional Intelligence and Decision-Making Styles in Lebanese Universities Medical Students. BMC Psychol. 2020, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üngür, G.; Karagözoğlu, C. Do Personality Traits Have an Impact on Anxiety Levels of Athletes during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Curr. Issues Personal. Psychol. 2021, 9, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Shi, M. Associations between Empathy and Big Five Personality Traits among Chinese Undergraduate Medical Students. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent-Lamarche, A.; Marchand, A.; Saade, S. A Multilevel Analysis of the Role Personality Play between Work Organization Conditions and Psychological Distress. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Huang, Y.; Yu, W.; Ming, W.-K.; Qi, F.; Wu, Y. A Moderated Mediation Model of the Relationship between Family Dynamics and Sleep Quality in College Students: The Role of Big Five Personality and Only-Child Status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmer, S.A.; Jacquin, K.M. When Perceived Physician Burnout Leads to Family Burnout: How Secondary Emotional Trauma Impacts Physician Spouses. Ment. Health Sci. 2023, 1, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, K.W.; Oddi, K.B.; Bridgett, D.J. Cognitive Correlates of Personality: Links between Executive Functioning and the Big Five Personality Traits. J. Individ. Differ. 2013, 34, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-J.; Chen, R.; Lu, H.-C. The Effect of Creators’ Personality Traits and Depression on Teamwork-Based Design Performance. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiman, N.; Fauzi, M.A.; Norizan, N.; Abdul Rashid, A.; Tan, C.N.-L.; Wider, W.; Ravesangar, K.; Selvam, G. Exploring Personality Traits in the Knowledge-Sharing Behavior: The Role of Agreeableness and Conscientiousness among Malaysian Tertiary Academics. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2024, 16, 1884–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengartner, M.P.; Kawohl, W.; Haker, H.; Rössler, W.; Ajdacic-Gross, V. Big Five Personality Traits May Inform Public Health Policy and Preventive Medicine: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional and a Prospective Longitudinal Epidemiologic Study in a Swiss Community. J. Psychosom. Res. 2016, 84, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blagov, P.S. Adaptive and Dark Personality in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Predicting Health-Behavior Endorsement and the Appeal of Public-Health Messages. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 12, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimstra, T.A.; Luyckx, K.; Germeijs, V.; Meeus, W.H.J.; Goossens, L. Personality Traits and Educational Identity Formation in Late Adolescents: Longitudinal Associations and Academic Progress. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, G.; Saraulli, D.; Perugini, M. Uncovering the Motivational Core of Traits: The Case of Conscientiousness. Eur. J. Pers. 2020, 34, 1073–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogg, T.; Roberts, B.W. Conscientiousness and Health-Related Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis of the Leading Behavioral Contributors to Mortality. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 130, 887–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokela, M.; Hakulinen, C.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Kivimäki, M. Personality Change Associated with Chronic Diseases: Pooled Analysis of Four Prospective Cohort Studies. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 2629–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, T.; Tsunekawa, Y.; Matsuoka, A.; Tanimura, D. Association between Big Five Personality Traits and Participation in Cardiac Rehabilitation in Japanese Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, X. V Football Scores on the Big Five Personality Factors across 50 States in the U.S. J. Sports Med. Doping Stud. 2012, 2012, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denburg, N.L.; Weller, J.A.; Yamada, T.H.; Shivapour, D.M.; Kaup, A.R.; LaLoggia, A.; Cole, C.A.; Tranel, D.; Bechara, A. Poor Decision Making among Older Adults Is Related to Elevated Levels of Neuroticism. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 37, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barlow, D.H.; Ellard, K.K.; Sauer-Zavala, S.; Bullis, J.R.; Carl, J.R. The Origins of Neuroticism. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 9, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasa, H.; Yoshida, Y. Personality and Health Literacy among Community-Dwelling Older Adults Living in Japan. Psychogeriatrics 2020, 20, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, S.J.; Jackson, J.J. The Role of Vigilance in the Relationship between Neuroticism and Health: A Registered Report. J. Res. Pers. 2018, 73, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269, W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetc, R.; Currie, M.; Lisy, K.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; et al. Chapter 7: Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozek, J.L.; Canelo-Aybar, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bowen, J.M.; Bucher, J.; Chiu, W.A.; Cronin, M.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falavigna, M.; Guyatt, G.H.; et al. GRADE Guidelines 30: The GRADE Approach to Assessing the Certainty of Modeled Evidence-An Overview in the Context of Health Decision-Making. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 129, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewidar, O.; Lotfi, T.; Langendam, M.W.; Parmelli, E.; Saz Parkinson, Z.; Solo, K.; Chu, D.K.; Mathew, J.L.; Akl, E.A.; Brignardello-Petersen, R.; et al. Good or Best Practice Statements: Proposal for the Operationalisation and Implementation of GRADE Guidance. BMJ Evid.-Based Med. 2023, 28, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Dixit, P.; Singh, P.; Kedia, N.; Tiwari, M.; Kumar, A. Pain Perception and Personality Trait toward Orthodontic Treatment. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2017, 7, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadu, A.; Chopra, S.; Jayan, B.; Kochar, G. Effect of the Personality Traits of the Patient on Pain Perception and Attitude toward Orthodontic Treatment. J. Indian Orthod. Soc. 2015, 49, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, V.; Liu, S.; Schrader, S.; Dean, J.A.; Stewart, K. Personality Traits as a Potential Predictor of Willingness to Undergo Various Orthodontic Treatments. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clijmans, M.; Lemiere, J.; Fieuws, S.; Willems, G. Impact of Self-Esteem and Personality Traits on the Association Betwee n Orthodontic Treatment Need and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life i n Adults Seeking Orthodontic Treatment. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydoğan, C. Extraversion and Openness to Experience Moderate the Relationship between Orthodontic Treatment Need and Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Adolescents: (A Cross-Sectional Study). Angle Orthod. 2018, 88, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Omiri, M.; Alhaija, E.A.A. Factors Affecting Patient Satisfaction after Orthodontic Treatment. Angle Orthod. 2006, 76, 422–431. [Google Scholar]

- Abu Alhaija, E.S.; Aldaikki, A.; Al-Omairi, M.K.; Al-Khateeb, S.N. The Relationship between Personality Traits, Pain Perception and Attitude toward Orthodontic Treatment. Angle Orthod. 2010, 80, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoneim, S.H.; Afif, K.S. The Effect of Personality Traits on Patient Compliance With Clear Aligners. Cureus 2024, 16, e74922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarul, M.; Lewandowska, B.; Kawala, B.; Kozanecka, A.; Antoszewska-Smith, J. Objectively Measured Patient Cooperation during Early Orthodontic Trea Tment: Does Psychology Have an Impact? Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017, 26, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper-Kazaz, R.; Ivgi, I.; Canetti, L.; Bachar, E.; Tsur, B.; Chaushu, S.; Shalish, M. The Impact of Personality on Adult Patients’ Adjustability to Orthodontic Appliances. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado, J.; Sierra, Á.; Gallón, A.; Álvarez, C.; Baccetti, T. Relationship between Personality Traits and Cooperation of Adolescent Orthodontic Patients. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nazeh, A.A.; Alshahrani, I.; Badran, S.A.; Almoammar, S.; Alshahrani, A.; Almomani, B.A.; Al-Omiri, M.K. Relationship between Oral Health Impacts and Personality Profiles among Orthodontic Patients Treated with Invisalign Clear Aligners. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Alhaija, E.S.; Abu Nabaa, M.A.; Al Maaitah, E.F.; Al-Omairi, M.K. Comparison of Personality Traits, Attitude toward Orthodontic Treatment, and Pain Perception and Experience before and after Orthodontic Treatment. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoal, S.; Gonçalves, M.; Salvador, P.; Azevedo, R.; Leite, M.; Pinho, T. The Relationship between Personality Profiles and the Esthetic Perception of Orthodontic Appliances. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 2024, 8827652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beļajevs, D.; Jākobsone, G. Relationship Between Personality Factors and Cooperation Level of Adult Patients During Invisalign Treatment: A Pilot Study. Balt. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modh, A.; Kubavat, A.; Desai, M.; Gor, J.; Vaghela, A. Pain Perception and Attitude towards Orthodontic Treatment of Treated and Untreated Subjects. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2019, 7, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E-Vien, M.; Rahman, U.S.B.A.; Misra, S.; Saxena, K. Pain Perception, Knowledge, Attitude, and Diet Diversity in Patients Undergoing Fixed Orthodontic Treatment: A Pilot Study. Turk. J. Orthod. 2024, 37, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, H.; Nissinen, J.; Lehtiniemi, H.; Salo, T.; Riipinen, P.; Miettunen, J. The Association Between Dental Anxiety And Psychiatric Disorders And Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2018, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, F.; Bos, A. Satisfaction with Orthodontic Treatment. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampraki, E.; Papaioannou, F.; Mylonopoulou, I.-M.; Pandis, N.; Sifakakis, I. Correlations among Satisfaction Parameters after Orthodontic Treatment. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2024, 29, e2424180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, E.; Shelton, A.; Hodge, T.; Morris, D.; Bekker, H.; Fletcher, S.; Barber, S. Patient-Reported Experience and Outcomes from Orthodontic Treatment. J. Orthod. 2020, 47, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwadei, S.H.; Almotiry, K.; AlMawash, A.; Alwadei, F.H.; Alwadei, A.H. Parental Satisfaction with Their Children’s Rapid Palatal Expansion Treatment Provided by Orthodontists and Pediatric Dentists. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2021, 15, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shammary, N.; Asimakopoulou, K.; McDonald, F.; Newton, J.T.; Scambler, S. How Is Adult Patient Adherence Recorded in Orthodontists’ Clinical Notes? A Mixed-Method Case-Note Study. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 1807–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, S.R.; Alsaggaf, D.H. Adherence to Dietary Advice and Oral Hygiene Practices Among Orthodontic Patients. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umaki, T.M.; Umaki, M.R.; Cobb, C.M. The Psychology of Patient Compliance: A Focused Review of the Literature. J. Periodontol. 2012, 83, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodi-Smith, J.; Jackson, J.; Bogg, T.; Walton, K.; Wood, D.; Harms, P.; Roberts, B.W. Mechanisms of Health: Education and Health-Related Behaviours Partially Mediate the Relationship between Conscientiousness and Self-Reported Physical Health. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, M.; Brink, E.; Lundgren, J.; Lötvall, J. The Influence of Personality Traits on Reported Adherence to Medication in Individuals with Chronic Disease: An Epidemiological Study in West Sweden. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdallah, M.; Hamdan, M.; Dar-Odeh, N. Traditional vs. Digital Communication Channels for Improving Compliance with Fixed Orthodontic Treatment. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, N.; Baherimoghadam, T.; Bassagh, N.; Hamedani, S.; Bassagh, E.; Hashemi, Z. The Impact of General Self-Efficacy and the Severity of Malocclusion on Acceptance of Removable Orthodontic Appliances in 10- to 12-Year-Old Patients. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, R.; Sathasivam, H.P.; Mohamednor, L.; Yugaraj, P. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Patients towards Orthodontic Treatment. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banozic, A.; Miljkovic, A.; Bras, M.; Puljak, L.; Kolcic, I.; Hayward, C.; Polasek, O. Neuroticism and Pain Catastrophizing Aggravate Response to Pain in Healthy Adults: An Experimental Study. Korean J. Pain 2018, 31, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorek, M.; Jarząbek, A.; Sycińska-Dziarnowska, M.; Gołąb, S.; Krawczyk, K.; Spagnuolo, G.; Woźniak, K.; Szyszka-Sommerfeld, L. The Association between Patients’ Personality Traits and Pain Perception during Orthodontic Treatment: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1469992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgaeva, E.E.; Williams, F.M.K.; Zaytseva, O.O.; Freidin, M.B.; Aulchenko, Y.S.; Suri, P.; Tsepilov, Y.A. Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study of Personality Traits Reveals a Positive Feedback Loop Between Neuroticism and Back Pain. J. Pain 2023, 24, 1875–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghaziarati, A.; Jun, H.; Dai, G.-S. Mind-Body Interactions in Chronic Pain Sufferers: A Qualitative Study on Personality Factors. J. Personal. Psychosom. Res. 2024, 1, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvers, K.; Hood, A. The Role of Positive Traits and Pain Catastrophizing in Pain Perception. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2013, 17, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grouper, H.; Eisenberg, E.; Pud, D. More Insight on the Role of Personality Traits and Sensitivity to Experimental Pain. J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 1837–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasnani, K.; Baguio, R.M.; Yap, R.J.C. Finding Strength in Time: Present-Fatalistic Time Perspective’s Mediating Role on Extraversion and Mental Pain Tolerance. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 2025, 44, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Studies involving adolescents and adults undergoing or having undergone orthodontic treatment | Studies involving patients with syndromes, cognitive impairments, or those undergoing treatments other than orthodontic appliances |

| Studies regarding the relationship between personality traits and patient-related outcomes (pain perception, OHRQoL, attitude toward orthodontic treatment, satisfaction, and compliance) | Studies that do not report the relationship between personality traits and patient-related outcomes |

| Studies using validated and standardized instruments to measure personality traits | Studies do not use validated tools for personality traits |

| Observational studies (cross-sectional, longitudinal, and cohort) | Case reports, case series, editorials, reviews, meta-analyses, and unpublished data |

| Database | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed/MEDLINE | ((orthodontic [Title/Abstract] OR orthodontics [Title/Abstract]) AND (personality [Title/Abstract] OR “personality traits” [Title/Abstract]) AND (attitude [Title/Abstract] OR satisfaction [Title/Abstract] OR pain [Title/Abstract] OR compliance [Title/Abstract] OR cooperation [Title/Abstract] OR “quality of life” [Title/Abstract] OR “treatment outcome” [Title/Abstract])) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (orthodontic OR orthodontics) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (personality OR “personality traits”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (attitude OR satisfaction OR pain OR compliance OR cooperation OR “quality of life” OR “treatment outcome”) |

| Web of Science | TS = (orthodontic OR orthodontics) AND TS = (personality OR “personality traits”) AND TS = (attitude OR satisfaction OR pain OR compliance OR cooperation OR “quality of life” OR “treatment outcome”) |

| ScienceDirect | (orthodontic OR orthodontics) AND (“personality traits” OR personality) AND (attitude OR pain OR satisfaction OR compliance OR “quality of life”) |

| Google Scholar | (orthodontic OR orthodontics) AND (personality OR “personality traits”) AND TS = (attitude OR satisfaction OR pain OR compliance OR cooperation OR “quality of life” OR “treatment outcome”) |

| Study (Authors, Year) | Population Characteristics | Instrument Used | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Omiri et al. (2006) [56] | 50 young adults aged 13–28 years. | Personality traits assessment by the NEO-FFI. Patient satisfaction measurement after orthodontic treatment with DIDL questionnaire. | Higher neuroticism scores were associated with lower satisfaction with dentition after orthodontic treatment. Extroversion and consciousness were positively correlated with satisfaction with appearance and with oral comfort. |

| Gender distribution: 20 males and 30 females. | Age, sex, and pretreatment orthodontic treatment need did not affect patient satisfaction. | ||

| Amado et al. (2008) [61] | 70 adolescents aged 12–15 years. | Personality assessment by 16PF-APQ. | No statistically significant relationships were found between cooperation and personality traits, gender, or age in adolescent orthodontic patients. |

| Gender distribution: 24 males and 46 females. | Cooperation assessment by OPCS. | Personality traits alone do not predict cooperation during orthodontic treatment in adolescents. | |

| Abu Alhaijaa et al. (2010) [57] | 400 participants divided into two groups: 200 untreated (mean age of 21.50 years) and 200 treated subjects (mean age of 20.92 years), equally divided by gender. | Personality traits evaluation with NEO-FFI. | Personality traits did not affect attitude toward orthodontic treatment or pain perception. |

| Equal number of males and females (100 each for the group). | Pain perception and attitude toward orthodontic treatment measurement using a VAS scale and VAS marked at 10 mm intervals, respectively. | Gender was the only variable affecting pain perception, with females reporting more pain than males. | |

| A more positive attitude was found in patients who experienced less pain during orthodontic treatment. | |||

| Hansen et al. (2013) [53] | 96 adolescents aged 12–16 years. | Personality traits evaluation with modified BFI-10. | Personality traits, particularly agreeableness, significantly predict willingness to undergo orthodontic treatments. |

| Gender distribution: 39 males and 57 females. | Willingness to undergo treatment measurement by weighted Kappa Statistics for Test-Retest Reliability Questionnaire Assessment. | Agreeableness was positively associated with five treatment modalities, while conscientiousness and neuroticism showed negative associations with specific treatments. | |

| Age and gender were not significant predictors of treatment willingness. | |||

| Cooper-Kazaz et al. (2013) [60] | 68 adult patients aged 19–60 years divided into three groups (buccal appliance, lingual appliance, and clear aligner). | Psychological traits evaluation using the BSI Inventory and the NVS Scale before treatment. | Somatization influenced the choice of lingual and clear aligner appliances, with anxious individuals preferring these options. |

| Gender distribution: 23 males and 45 females. | Patients’ perceptions of pain and dysfunction evaluation using an HRQOL questionnaire and VAS scale. | Reduced self-esteem regulation was associated with increased pain across all orthodontic appliances. | |

| Buccal appliances allow a more significant impact of personality traits on adjustability than lingual and clear aligner appliances. | |||

| Abu Alhaijaa et al. (2015) [63] | 100 adolescents and young adults aged approximately 17.5 to 19.15 years. | Personality traits assessment using the NEO-FFI. | Personality traits such as neuroticism, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness improved after orthodontic treatment. |

| Equal number of males and females (50 each). | Pain perception and attitudes toward orthodontic treatment measurement using VAS scale. | Attitude toward orthodontic treatment improved after orthodontic treatment. | |

| The pain experienced during orthodontic treatment was like expected pain before treatment. | |||

| Kadu et al. (2015) [52] | 200 adolescents aged 14–18 years divided into two groups (treated and untreated), each consisting of 100. | Personality traits evaluation with NEO-FFI. | Pain perception was similar for treated and untreated groups, indicating no effect of orthodontic treatment on pain perception. |

| Equal number of males and females (100 each). | Pain perception and attitude measurement using the VAS scale. | Personality traits, particularly neuroticism and conscientiousness, significantly influenced pain perception and attitude toward orthodontic treatment. | |

| Gender and treatment status did not affect pain perception or attitude towards orthodontic treatment. | |||

| Clijmans et al. (2015) [54] | 189 adults aged 17–64 years (mean age 31.3 years). | Personality traits evaluation with the Dutch adaptation of NEO-FFI. | There is a significant association between orthodontic treatment need and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), with higher treatment need correlating with worse OHRQoL. |

| Gender distribution: 55 males and 134 females. | Self-esteem assessment with the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSES). | Self-esteem is significantly associated with OHRQoL, where higher self-esteem correlates with better OHRQoL. | |

| OHRQoL measurement by OHIP-14. | Certain personality traits are associated with OHRQoL, but neither self-esteem nor personality traits moderate the relationship between treatment need and OHRQoL. | ||

| Orthodontic treatment need assessment by IOTN. | |||

| Sigh et al. (2017) [51] | 300 adolescents and young adults aged 15–20 years divided into untreated and treated groups (150 each). | Personality traits evaluation with NEO-FFI. | Attitude, personality traits, and pain perception significantly influence patient cooperation and the success of orthodontic treatment. |

| Equal number of males and females (75 males and 75 females in each group). | Pain perception and attitude assessment using a VAS scale. | No significant difference in pain perception was found between treated and untreated groups or between genders. | |

| Higher levels of neuroticism are associated with increased pain perception, while conscientiousness is directly proportional to pain perception. | |||

| Sarul et al. (2017) [59] | 38 adolescents aged 9–12 years. | Patient temperament and personality traits assessment by the EAS-C Temperament Questionnaire, Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES), NEO-FFI, and Parental Attitude Scale. | Psychological traits such as high self-efficacy, conscientiousness, and strict parental requirements positively correlate with better compliance in wearing removable orthodontic appliances. |

| Equal number of males and females (19 each). | Psychological assessments can predict patient compliance, suggesting their potential use in planning orthodontic treatments. | ||

| Aydoğan (2018) [55] | 230 adolescents aged 11–14 years (mean age 12.48 years). | Personality traits assessment by BPTI. | Personality traits such as extraversion and openness to experience moderate the relationship between orthodontic treatment need and oral health-related quality of life in adolescents. |

| Gender distribution: 105 males and 125 females. | Dispositional optimism evaluation with the Revised Life Orientation Test. | Adolescents with higher levels of extraversion and openness to experience are less negatively affected by their orthodontic treatment needs. | |

| Orthodontic treatment need measurement by ICON. | |||

| Al Nazeh et al. (2020) [62] | 50 adults aged 18–48 years (mean age 27.62 years). | Personality assessment by NEO-FFI. | Females experienced a significant reduction in negative oral health impacts after Invisalign treatment. |

| Gender distribution: 24 males and 26 females. | OHRQoL measurement by OHIP. | Among males, personality traits such as openness, extraversion, and conscientiousness predicted oral health impacts after treatment. | |

| Personality traits did not predict oral health impacts for females. | |||

| Pascoal et al. (2024) [64] | 461 adults aged 18–70 years. Gender distribution: 93 males and 368 females. | Personality traits assessment using the NEO-FFI inventory. Questionnaire with sociodemographic variables and aesthetic perception of orthodontic appliances. | Personality traits such as agreeableness and openness are associated with a preference for aligners, while neuroticism is linked to a preference for fixed appliances. Personality traits significantly influence aesthetic perception and decisions regarding orthodontic treatment, impacting patient satisfaction. |

| Ghoneim and Afif (2024) [58] | 67 participants aged 12–60 years. Gender distribution: 18 males and 49 females. | BFI-10 tool for personality traits evaluation. Questionnaire on compliance behavior (measured by adherence to follow-up visits and aligner wear time). | No significant correlation was found between personality traits and compliance with clear aligner therapy. Compliance was higher among younger patients (aged 12–34) and males. Patients undergoing treatment for one year or less showed better adherence. |

| Belajevs and Jākobsone (2024) [65] | 22 participants aged ≥18 years Gender distribution: 3 males and 19 females. | Personality traits assessment with Latvian version NEO-FFI. Cooperation measurement by orthodontists and premolar expansion measurements. | Higher neuroticism scores are associated with noncompliance treatment, including missed appointments and discrepancies in aligner use. Extraversion correlates with complaints about the treatment process and poor hygiene, while conscientiousness is linked to better financial control and parental involvement. |

| Criteria | Al-Omiri et al. (2006) [56] | Amado et al. (2008) [61] | Abu Alhaijaa et al. (2010) [57] | Hansen et al. (2013) [53] | Cooper-Kazaz et al. (2013) [60] | Abu Alhaijaa et al. (2015) [63] | Kadu et al. (2015) [52] | Clijmans et al. (2015) [54] | Sigh et al. (2017) [51] | Sarul et al. (2017) [59] | Aydoğan (2018) [55] | Al Nazeh et al. (2020) [62] | Pascoal et al. (2024) [64] | Ghoneim and Afif (2024) [58] | Beļajevs and Jākobsone (2024) [65] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q5 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Q6 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear |

| Q7 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Q8 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| RISK OF BIAS | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate |

| Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain Perception | Attitude | Compliance | Satisfaction | OHRQoL | |

| Number of studies (participants) | 5 studies [51,52,57,60,63] (1068 patients) | 5 studies [51,52,53,57,63] (1096 patients) | 4 studies [58,59,61,65] (197 patients) | 2 studies [56,64] (511 patients) | 4 studies [54,55,56,62] (519 patients) |

| Study design | Observational studies (mainly cross-sectional and one study including a short-term prospective observation) | Observational studies (cross-sectional) | Observational studies (mostly cross-sectional and one longitudinal observational study) | Observational studies (cross-sectional) | Observational studies (cross-sectional) |

| Risk of Bias | Not serious | Not serious | Serious a | Not serious | Not serious |

| Inconsistency | Not serious | Not serious | Serious b | Serious b | Serious b |

| Indirectness | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Serious c | Not serious |

| Imprecision | Serious d | Serious d | Serious d | Serious d | Serious d |

| Other considerations | None e | None e | None e | None e | None e |

| Effect of direction | Higher neuroticism and maladaptive traits are associated with increased pain perception. | Extraversion, openness, and conscientiousness are associated with more positive treatment attitudes. | Higher conscientiousness and self-efficacy are associated with better compliance, but some studies show mixed results. | Higher neuroticism is associated with lower satisfaction; extraversion and openness are linked to better aesthetic perceptions. | Higher neuroticism is associated with poorer OHRQoL, while extraversion and openness buffer negative impacts. |

| Overall GRADE certainty | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low | ⨁◯◯◯ Very low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicita, F.; Nicita, A.; Nicita, F. Influence of Personality Traits on Pain Perception, Attitude, Satisfaction, Compliance, and Quality of Life in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15095075

Nicita F, Nicita A, Nicita F. Influence of Personality Traits on Pain Perception, Attitude, Satisfaction, Compliance, and Quality of Life in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(9):5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15095075

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicita, Fabiana, Arianna Nicita, and Francesco Nicita. 2025. "Influence of Personality Traits on Pain Perception, Attitude, Satisfaction, Compliance, and Quality of Life in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 9: 5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15095075

APA StyleNicita, F., Nicita, A., & Nicita, F. (2025). Influence of Personality Traits on Pain Perception, Attitude, Satisfaction, Compliance, and Quality of Life in Orthodontics: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 15(9), 5075. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15095075