Femoral Neck Fractures in Elderly Patients: Dual Mobility Cup Arthroplasty or Hemiarthroplasty? A Narrative Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

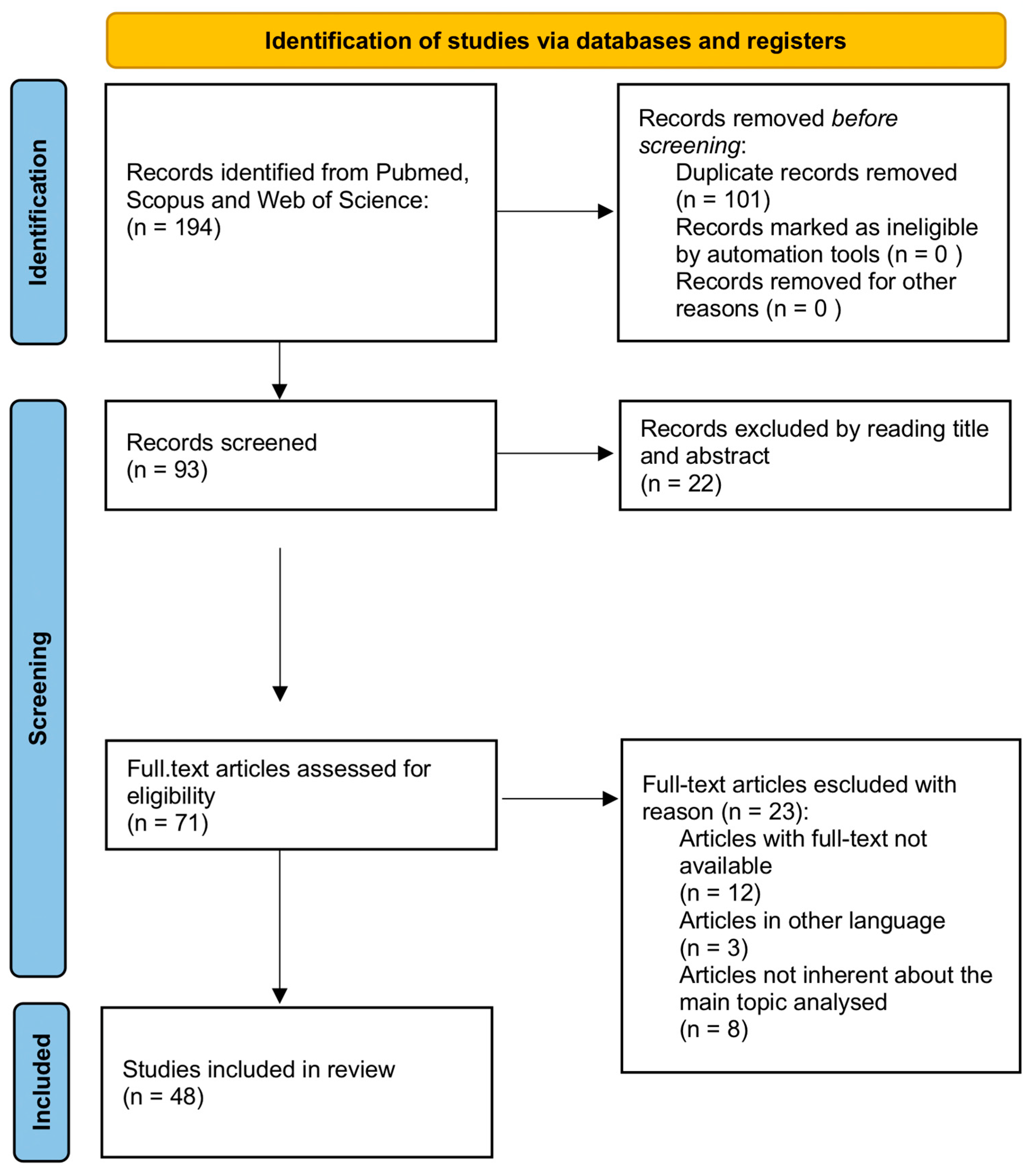

2. Methods

3. Anatomic Reference

4. Diagnosis

5. Classification

- Type 1: Incomplete and undisplaced fracture, where the bone is not fully fractured and remains in proper alignment;

- Type 2: Complete, undisplaced fracture, where the bone is fully fractured but maintains its original position without displacement (Figure 1);

- Type 3: Partial displacement with misalignment of the trabecular bone, where the fracture fragments begin to shift out of alignment but are not fully displaced;

- Type 4: Complete displacement, where the fracture results in significant separation and displacement of the bone fragments.

- Type 1: The fracture angle is less than 30°, typically representing a stable fracture;

- Type 2: The fracture angle ranges between 30° and 50°, indicating an intermediate level of stability;

- Type 3: The fracture angle is greater than 50°, which is associated with an unstable fracture and a higher risk of complications.

6. Treatment

6.1. Conservative Treatment

- Short life expectancy: In patients with a limited life expectancy, the risks associated with surgery may outweigh the potential benefits. In such cases, where the patient may not survive long enough to fully recover from surgery, conservative management might be preferred to avoid unnecessary complications.

- Chronic fractures with signs of consolidation: In cases where the fracture has occurred long ago (inveterate fractures), and there are signs of partial or complete consolidation (healing) of the fracture, non-surgical management may be considered. This could be appropriate when the bone is healing in a satisfactory position and there is no need for surgical realignment.

- Patients who are bedridden: For patients who are continuously bedridden and unable to bear weight, the need for surgical intervention might be reduced. In these cases, the focus would be on pain management and maintaining mobility to the extent possible, with surgery being deemed unnecessary due to the patient’s inability to benefit from functional recovery post-surgery.

- Patient refusal of surgical treatment: In some cases, patients may refuse surgery for personal, medical, or psychological reasons. When a patient makes an informed decision to decline surgical treatment, non-surgical management, including pain control and rehabilitation, may be pursued as an alternative, provided the patient understands the risks and limitations of this approach.

6.2. Hemiarthroplasty (HA)

6.3. Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA)

6.4. Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty (DM-THA)

7. Discussion

Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PFF | Proximal femur fracture |

| HA | Hemiarthroplasty |

| THA | Total hip arthroplasty |

| DM-THA | Dual mobility total hip arthroplasty |

| AO | Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen |

References

- Unim, B.; Minelli, G.; Da Cas, R.; Manno, V.; Trotta, F.; Palmieri, L.; Galluzzo, L.; Maggi, S.; Onder, G. Trends in Hip and Distal Femoral Fracture Rates in Italy from 2007 to 2017. Bone 2021, 142, 115752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscitelli, P.; Tarantino, U.; Chitano, G.; Argentiero, A.; Neglia, C.; Agnello, N.; Saturnino, L.; Feola, M.; Celi, M.; Raho, C.; et al. Updated incidence rates of fragility fractures in Italy: Extension study 2002–2008. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 2011, 8, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arakaki, H.; Owan, I.; Kudoh, H.; Horizono, H.; Arakaki, K.; Ikema, Y.; Shinjo, H.; Hayashi, K.; Kanaya, F. Epidemiology of hip fractures in Okinawa, Japan. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2011, 29, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullberg, B.; Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporos. Int. 1997, 7, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oulianski, M.; Rosinsky, P.J.; Fuhrmann, A.; Solokov, R.; Arriola, R.; Lubovsky, O. Decrease in incidence of proximal femur fractures in the elderly population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case-control study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, U.G.; Viganò, M.; de Girolamo, L.; Banfi, G.; Salvatore, G.; Denaro, V. Epidemiology and Management of Proximal Femoral Fractures in Italy between 2001 and 2016 in Older Adults: Analysis of the National Discharge Registry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viganò, M.; Pannestrì, F.; Listorti, E.; Banfi, G. Proximal hip fractures in 71,920 elderly patients: Incidence, epidemiology, mortality and costs from a retrospective observational study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.; Szymshi, D.; Kurtz, S.M.; Lowenberg, D.W.; Alt, W.; Lau, E.C.; Rupp, M. Epidemiology and treatment of proximal femoral fractures in the elderly U.S. population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M.L.; Hartog, D.D.; Panneman, M.J.M.; Polinder, S.; Verhofstad, M.H.J.; Van Lieshout, E.M.M. Trends in incidence, health care consumption, and costs for proximal femoral fractures in the Netherlands between 2000 and 2019: A nationwide study. Osteoporos. Int. 2023, 34, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K.C.; Timothy Brox, W.; Jevsevar, D.S.; Sevarino, K. Management of hip fractures in the elderly. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2015, 23, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zofka, P. Bipolar hip hemiarthroplasty. Acta Chir. Orthop. Traumatol. Cech. 2007, 74, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyen, O. Hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty in recent femoral neck fractures? Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2019, 105, S95–S101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingue, G.; Warren, D.; Koval, K.J.; Riehl, J.T. Complications of Hip Hemiarthroplasty. Orthopedics 2023, 46, e199–e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizkapan, T.B.; Misi, A.; Uzun, E.; Oguzkaya, S.; Ozcamdalli, M. Factors affecting dislocation after bipolar hemiarthroplasty in patients with femoral neck fracture. Injury 2020, 51, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graulich, T.; Graeff, P.; Jaiman, A.; Nicolaides, S.; Pacha, T.O.; Orgel, M.; Macke, C.; Omar, M.; Krettek, C.; Liodakis, E. Risk factors for dislocation after bipolar hemiarthroplasty: A retrospective case-control study of patients with CT data. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2021, 31, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, M.; Di Via, D.; Vaccalluzzo, M.S.; Costarella, L.; Pavone, V.; Testa, G. Comparative Analysis of Cemented and Cementless Straight-Stem Prostheses in Hip Replacement Surgery for Elderly Patients: A Mid-Term Follow-up Study. Prosthesis 2024, 6, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsetto, A.; Dobransky, J.; Kreviazuk, C.; Papp, S.; Beaulé, P.E.; Grammatopoulos, G. Instability after hip hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture: An unresolved problem. Can. J. Surg. 2022, 65, E128–E134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofa, S.A.; Lupica, G.M.; Lee, O.C.; Sherman, W.F. Complications following total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures in patients with a history of lumbar spinal fusion. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2023, 143, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheras, G.A.; Pallis, D.; Tsivelekas, K.; Ampadiotaki, M.M.; Lepetsos, P.; Tzefronis, D.; Kateros, K.; Papadakis, S.A. Acetabular erosion after bipolar hip hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture in elderly patients: A retrospective study. Hip Int. 2024, 34, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscevic, M.; Smrke, D. Structural differences between hip endoprostheses, and implications on a hip kinetics. Bosn. J. Basic. Med. Sci. 2005, 5, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavkovic, N.; Vukasinovic, Z.; Bascarevic, Z.; Vukmanovic, B. Total hip arthroplasty. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek. 2012, 140, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, T.; Philippot, R.; Klasan, A.; Putnis, S.; Leie, M.; Boyer, B.; Farizon, F. Dual mobility acetabular cups for total hip arthroplasty: Advantages and drawbacks. Expert. Rev. Med. Devices 2018, 15, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, D.P.; Waever, D.; Thorninger, R.; Donnelly, W.J. Hemiarthroplasty vs. Total Hip Arthroplasty for the Management of Displaced Neck of Femur Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, 1837–1843.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldestein, A.I.; Dillingham, T.R.; McGinley, E.L.; Pezzin, L.E. Hemiarthroplasty Versus Total Hip Arthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fracture in Elderly Patients: Twelve-Month Risk of Revision and Dislocation in an Instrumental Variable Analysis of Medicare Data. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2023, 105, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellova, P.; Goronzy, J.; Riedel, R.; Grothe, T.; Hartmann, A.; Gunther, K.P. Dual-Mobility Cups in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty. Z. Orthop. Unfallchirurgie 2023, 161, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.L.; Pallottino, A.d.B.; Franco, J.S.; Chami, S.M.; Scorza, B.J.; de Morais, B.B. Early Intraprosthetic Dislocation of Total Hip Arthroplasty with Double Mobility Implant: Case Report. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2022, 59, e475–e478. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, A.; Desai, M.; Somani, V.; Shahare, P.; Agarwal, R. Intraprosthetic Dislocation of Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2023, 13, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, A.J.; Buchalter, D.B.; Kugelman, D.N.; Deshmukh, A.J.; Aggarwal, V.K.; Rozell, J.C. Dual Mobility in Total Hip Arthroplasty. Bull. Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2022, 80, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed, R.A.; Abdalaziz, A.; Veivenn, V.Y.; Tetali, S.R.; Choudry, Q.A.; Sloan, A.G.; Helm, A. Is dual mobility cup total hip replacement associated with increased incidence of heterotopic ossification compared to conventional total hip replacements in fracture neck of femur patients? Injury 2020, 51, 2676–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Heumen, M.; Heesterbeek, P.J.C.; Swiestra, B.A.; Van Hellemondt, G.G.; Goosen, J.H.M. Dual mobility acetabular component in revision total hip arthroplasty for persistent dislocation: No dislocations in 50 hips after 1–5 years. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2015, 16, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Li, P.; Ning, N. The comparison between total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in patients with femoral neck fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on 25 randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukebous, B.; Boutroux, P.; Zahi, R.; Azmy, C.; Guillon, P. Comparison of dual mobility total hip arthroplasty and bipolar arthroplasty for femoral neck fractures: A retrospective case-control study of 199 hips. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2018, 104, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.T.; Yoo, J.H.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, S.; Hwang, J. Dual mobility hip arthroplasty provides better outcomes compared to hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: A retrospective comparative clinical study. Int. Orthop. 2018, 42, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahad, S.; Khan, M.Z.N.; Aqueel, T.; Hashmi, P. Comparison of bipolar hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty with dual mobility cup in the treatment of old active patients with displaced neck of femur fracture: A retrospective cohort study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2019, 45, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bensen, A.S.; Jakobsen, T.; Krarup, N. Dual mobility cup reduces dislocation and re-operation when used to treat displaced femoral neck fractures. Int. Orthop. 2014, 38, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotini, M.; Farinelli, L.; Natalini, L.; De Rosa, F.; Politano, R.; Cianforlini, M.; Pacetti, E.; Pasquinelli, F.M.; Gigante, A. Is Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty Surgery More Aggressive than Hemiarthroplasty when Treating Femoral Neck Fracture in the Elderly? A Multicentric Retrospective Study on 302 Hips. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2022, 13, 21514593221081375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukaj, S.; Zhuri, O.; Ukaj, F.; Podvorica, V.; Grezda, K.; Caton, J.; Prudhon, J.L.; Krasniqi, S. Dual Mobility Acetabular Cup Versus Hemiarthroplasty in Treatment of Displaced Femoral Neck Fractures in Elderly Patients: Comparative Study and Results at Minimum 3-Year Follow-up. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2019, 10, 2151459319848610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcaregni, J.; Martinov, S.; Chahidi, E.; Jennart, H.; Bui Quoc, E.; Dimanche, M.C.; Hupez, A.; Bhogal, H.; Hafez, K.; Callewier, A.; et al. Hip fractures re-operation compared with death at two year in elderly patients: Lowest risk of revision with dual mobility total hip arthroplasty than with bipolar hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation of Garden I and II. Int. Orthop. 2022, 46, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Albanese, K.M.; Deshmane, P.; Patil, N.; Larsen, D.A.; Ordway, N.R. Dual-Mobility Articulations in Femoral Neck Fractures: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-analysis of the Outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2021, 29, e618–e627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabori-Jensen, S.; Hansen, T.B.; Bovling, S.; Aalund, P.; Homilius, M.; Stilling, M. Good function and high patient satisfaction at mean 2.8 years after dual mobility THA following femoral neck fracture: A cross-sectional study of 124 patients. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canton, G.; Monghnie, A.; Ratti, C.; Murena, L. Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty in the Treatment of Emoral Neck Fracture: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Recent. Adv. Arthroplast. 2018, 2, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, P.; Philippe, R.; Ehlinger, M.; Roche, O.; Bonnomet, F.; Molé, D.; Fessy, M.-H. Dual mobility cups hip arthroplasty as a treatment for displaced fracture of the femoral neck in the elderly. A prospective, systematic, multicenter study with specific focus on postoperative dislocation. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2012, 98, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, I.; Moreta, J.; Jimenez, I.; Legarreta, M.J.; de Los Mozos, J.L.M. Dual-mobility cups in total hip arthroplasty after femoral neck fractures: A retrospective study comparing outcomes between cemented and cementless fixation. Injury 2021, 52, 1467–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashed, R.A.; Sevenoaks, H.; Shabaan, A.M.; Choudry, Q.A.; Hammad, A.S.; Kasem, M.S.; El Khadrawe, T.A.; El Dakhakhny, M.M. Functional outcome and health related quality of life after dual mobility cup total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures in middle aged Egyptian patients. Injury 2018, 49, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nich, C.; Vandenbussche, E.; Augereau, B.; Sadaka, J. Do Dual-Mobility Cups Reduce the Risk of Dislocation in Total Hip Arthroplasty for Fractured Neck of Femur in Patients Aged Older Than 75 Years? J. Arthroplasty 2016, 31, 1256–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, G.; Cao, L.; Sun, W.; Zang, X.; Xiong, N.; Wang, S.; Yu, W.; Liu, Q.; Lin, H. Dual-Mobility Cup Total Hip Arthroplasty for Displaced Femoral Neck Fractures: A Retrospective Study With a Median Follow-Up of 5 Years. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2021, 12, 21514593211013244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrith, B.; Courtney, P.M.; Della Valle, C.J. Outcomes of dual mobility components in total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review of the literature. Bone Jt J. 2018, 100, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinnai, Y.; Homma, Y.; Baba, T.; Zhuang, X.; Kaneko, K.; Ishijima, M. Use of Dual Mobility Acetabular Component and Anterior Approach in Patients with Displaced Femoral Neck Fracture. J. Arthroplasty 2021, 36, 2530–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, C.C.; Barakat, H.B.; Caton, J.H.; Najjar, E.N.; Samaha, C.T.; Yammine, K.F. Mortality Rate and Mid-Term Outcomes of Total Hip Arthroplasty Using Dual Mobility Cups for the Treatment of Femoral Neck Fractures in a Middle Eastern Population. J. Arthroplasty 2019, 34, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carulli, C.; Macera, A.; Matassi, F.; Civinini, R.; Innocenti, M. The use of a dual mobility cup in the management of recurrent dislocations of hip hemiarthroplasty. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2016, 17, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Deeb, M.A.; Said, M.M.; El-Rahman, T.M.A.; Attalah, A.H.A.A.; Abdelaziz, A.M.; Assan, Y.E. Dual Mobility Cup in Fractures of the Femoral Neck in Neuromuscular Disorders and Cognitive Dysfunction Patients above 60 years-old. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2023, 11, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, T.-F.; Huan, S.-W.; Luo, S.-M.; She, G.-R.; Wu, W.-R.; Chen, J.-Y.; Liu, N.; Zha, Z.-G. Outcomes of dual mobility articulation total hip arthroplasty in ipsilateral residual poliomyelitis. Int. Orthop. 2022, 46, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henawy, A.T.; Badie, A.A. Dual mobility total hip arthroplasty in hemiplegic patients. SICOT J. 2017, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, P.B.; Pawar, A.V.; Patel, G.B.; Rathod, P.P. Central Fracture-Dislocation of the Hip with Ipsilateral Femoral Neck Fracture in an Elderly Patient with Parkinsonism Managed with Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2024, 14, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, N.P.; Gagod, L.L.; Chandanwale, A.S.; Kumar, G.S.P.; Narvekar, M.; Kamble, M. The Neck of Femur Fracture in an Elderly Patient with Schizophrenia and Parkinsonism Managed with Dual Mobility Total Hip Replacement—A Rare Case Report. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2021, 11, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cnudde, P.H.J.; Natman, J.; Hailer, N.P.; Rogmark, C. Total, hemi, or dual-mobility arthroplasty for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in patients with neurological disease: Analysis of 9638 patients from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Bone Jt. J. 2022, 104, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Lin, C.C.; Anil, U.; Rivero, S.M. Arthroplasty treatment options for femoral neck fractures in the elderly: A network meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Injury 2024, 55, 111875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mufarrih, S.H.; Qureshi, N.Q.; Masri, B.; Noordin, S. Outcomes of total hip arthroplasty using dual-mobility cups for femoral neck fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hip Int. 2021, 31, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, R.L.; Vogl, W.; Mitchell, A.W.M. Gray’s Basic Anatomy, 3rd ed.; ELSEVIER: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 290, 292, 294. [Google Scholar]

- Mangano, G.R.A.; Avola, M.; Blatti, C.; Caldaci, A.; Sapienza, M.; Chiaramonte, R.; Vecchio, M.; Pavone, V.; Testa, G. Non-Adherence to Anti-Osteoporosis Medication: Factors Influencing and Strategies to Overcome It. A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Drake, R.L.; Vogl, A.W.; Mitchell, A.W.M.; Tibbits, R.; Richardson, P. Gray’s Atlas of Anatomy, 1st ed.; Churchill Livingston: London, UK, 2007; p. 279. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, L.; Warwick, D.; Nayagam, S. Apley’s System of Orthopaedics and Fractures, 9th ed.; Hachette UK Company: London, UK, 2010; p. 848. [Google Scholar]

- Hitesh Gopalan, U. Gopalan’s Evidence Based Orthopaedics Principles; International ed.; Sicot India Initiative; McMaster University: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2015; p. 347. [Google Scholar]

- Sluttilel, P.; Rossi, L.; Camino-Willhuber, G. Orthopaedics and Trauma, Current Conceps and Best Practices; Springer: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2024; p. 444. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, J.D.; Turner, S.P.; Buck, E. Hip Fractures: Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2022, 106, 675–683. [Google Scholar]

- Egol, K.A.; Koval, K.J.; Zuckerman, J. Handbook of Fractures, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; p. 382. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc, K.E.; Muncie, H.L., Jr.; LeBlanc, L.L. Hip fracture: Diagnosis, treatment, and secondary prevention. Am. Fam. Physician 2014, 89, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- White, T.O.; Mackenzie, S.P. McRae’s Orthopaedic Trauma and Emergency Fracture Management, 4th ed.; Elvesier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- Resnick, D.; Jacobson, J.A.; Chung, C.B.; Kransdorf, M.J.; Pathria, M.N. Bone and Joint Imaging, 4th ed.; Elvesier: St Louis, MO, USA, 2024; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, C.A. Fundamentals of Skeletal Radiology, 5th ed.; Elvesier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, R.; Banerjee, S. Proximal femoral fractures: Principles of management and review of literature. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2012, 3, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Uppal, H.S. Hip Fractures: Relevant Anatomy, Classification, and Biomechanics of Fracture and Fixation. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2019, 10, 2151459319859139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, P.G.; D’antoni, A.V.; Loukas, M.; Oskouian, R.J.; Tubbs, R.S. Hip fractures in the elderly-: A Clinical Anatomy. Clin. Anat. 2017, 30, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauwels, F.; Enke, F. Der Schenkelhalsbruch: Ein Mechanisches Problem; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Meinberg, E.G.; Agel, J.; Roberts, C.S.; Karam, M.D.; Kellam, J.F. Fracture and dislocation classification Compendium—2018. J. Orthop. Trauma 2018, 32, S1–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021 SIOT Guidelines, Proximal Femur Fractures in Elderly People. p. 39. Available online: https://www.sigot.org/allegato_docs/1600_LG_SIOT_fratturafemore2021.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2025).

| Author and Year | Title | Type of Study | N° of Patients | HA/THA/DM-THA/HA vs. DM-THA/HA vs. THA/HA vs. THA vs. DM THA | OUTCOMES | Follow-Up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zofka 2007 [11] | [Bipolar hip hemiarthroplasty] | Case series | 79 | HA | DM-THA offers less stress and strain on patients compared to THA. It provides greater stability and a lower risk of acetabular protrusion than THA. | 36 |

| Guyen 2019 [12] | Hemiarthroplasty or total hip arthroplasty in recent femoral neck fractures? | Review | HA vs. DM-THA | HA is recommended for patients who had limitations in physical activity, self-sufficiency, and walking ability prior to the fracture. | ||

| Domingue 2023 [13] | Complications of Hip Hemiarthroplasty | Review | HA | Common complications associated with HA treatment include dislocation, periprosthetic fractures, acetabular erosion, and leg-length discrepancy. Less frequent complications are neurovascular injury and capsular interposition. | ||

| Kizkapan 2020 [14] | Factors affecting dislocation after bipolar hemiarthroplasty in patients with femoral neck fracture | Retrospective case–control study | 208 | HA | Factors influencing dislocation in HA include pelvic morphological features and surgical factors. | 30.8 (12–48) |

| Graulich 2021 [15] | Risk factors for dislocation after bipolar hemiarthroplasty: a retrospective case–control study of patients with CT data | Retrospective case–control study | 39 | HA | All patients underwent pelvic computed tomography. Dementia and an insufficient posterior wall angle are associated with an increased risk of dislocation in HA. | 2 |

| Sapienza 2024 [16] | Comparative Analysis of Cemented and Cementless Straight-Stem Prostheses in Hip Replacement Surgery for Elderly Patients: A Mid-Term Follow-up Study. | Retrospective cohort study | 80 | The cemented group demonstrated better clinical outcomes, including higher Harris Hip Scores, WOMAC scores, and lower Visual Analog Scale, compared to the non-cemented group. | 42 (13–72) | |

| Falsetto 2022 [17] | Instability after hip hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture: an unresolved problem. | Retrospective case–control study | 18 | HA | Patient factors linked to an increased risk of dislocation following hip HA include dementia and a low preoperative lateral center-edge angle. | 24 |

| Ofa 2023 [18] | Complications following total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures in patients with a history of lumbar spinal fusion. | Case–control study | HA | Lumbar spine fusion is an independent risk factor for complications following hemiarthroplasty (HA) after a femoral neck fracture. | ||

| Macheras 2024 [19] | Acetabular erosion after bipolar hip hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture in elderly patients: a retrospective study | Retrospective study | 813 | HA | The authors assessed acetabular erosion through radiological examinations and evaluated functional deterioration using the modified Harris Hip Score (mHHS). | 12 |

| Biscevic 2005 [20] | Structural differences between hip endoprostheses, and implications on a hip kinetics | Comparative study | 90 | HA | Comparison of the kinetic characteristics of unipolar, bipolar, and total hip endoprostheses implanted following a dislocated femoral neck fracture | 3.6 years |

| Slavkovic 2012 [21] | [Total hip arthroplasty] | Review | THA tips and tricks | Surgical technique, biomaterials, design of the prosthesis, and fixation techniques in THA | ||

| Neri 2018 [22] | Dual mobility acetabular cups for total hip arthroplasty: advantages and drawbacks | review | DM THA | Discusses the advantages and disadvantages of dual mobility THA based on its 40-year history | ||

| Lewis 2019 [23] | Hemiarthroplasty vs. Total Hip Arthroplasty for the Management of Displaced Neck of Femur Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 1364 | HA vs. THA | Harris Hip Score and quality of life (Short Form 36), risk of dislocation | |

| Eldestein 2023 [24] | Hemiarthroplasty Versus Total Hip Arthroplasty for Femoral Neck Fracture in Elderly Patients: Twelve-Month Risk of Revision and Dislocation in an Instrumental Variable Analysis of Medicare Data. | Retrospective study | HA vs. THA | 12-month dislocation rate between HA and THA following femur neck fractures | 12 | |

| Bellova 2023 [25] | Dual Mobility Cups in Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty | Review | DM-THA | Advantages of DM-THA | ||

| Lima 2022 [26] | Early Intraprosthetic Dislocation of Total Hip Arthroplasty with Double Mobility Implant: Case Report | Case report | 1 | DM-THA | A complication after DM-THA: Intraprosthetic dislocation | |

| Shaikh 2023 [27] | Intraprosthetic Dislocation of Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Case Report and Review of Literature. | Case report + Literature review | 1 | DM THA | A complication after DM-THA: Intraprosthetic dislocation | |

| Clair 2022 [28] | Dual Mobility in Total Hip Arthroplasty | DM-THA | Advantages and complication of dual mobility cup | |||

| Rashed 2020 [29] | Is dual mobility cup total hip replacement associated with increased incidence of heterotopic ossification compared to conventional total hip replacements in fracture neck of femur patients? | Retrospective cohort study | 334 | DMTHA | Risk of heterotopic ossifications after DM THA | |

| Van Heumen 2015 [30] | Dual mobility acetabular component in revision total hip arthroplasty for persistent dislocation: no dislocations in 50 hips after 1–5 years | Retrospective cohort study | 49 | DM THA | Dislocation rate in revision total hip arthroplasty with dual mobility cup | 29 (12–66) |

| Tang 2020 [31] | The comparison between total hip arthroplasty and hemiarthroplasty in patients with femoral neck fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on 25 randomized controlled trials | Meta-analysis | 3223 | HA vs. THA | Harris Hip Score, Quality-of-Life EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) scores, rate of dislocation, acetabular erosion, blood loss, hospital length of stay | 24 |

| Boukebous 2018 [32] | Comparison of dual mobility total hip arthroplasty and bipolar arthroplasty for femoral neck fractures: A retrospective case–control study of 199 hips | Retrospective case–control study | 193 | HA vs. DM THA | Complication (dislocation, infection, medical complications, mortality) rate comparison | 24.2 |

| Kim 2018 [33] | Dual mobility hip arthroplasty provides better outcomes compared to hemiarthroplasty for displaced femoral neck fractures: a retrospective comparative clinical study | Retrospective cohort study | 168 | HA vs. DM THA | Intraoperative Blood loss, length of operation, one-year mortality. Harris Hip Score | 22 |

| Fahad 2019 [34] | Comparison of bipolar hemiarthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty with dual mobility cup in the treatment of old active patients with displaced neck of femur fracture: A retrospective cohort study. | Retrospective cohort study | 104 | HA vs. DM THA | Postoperative surgical complications, including dislocation, fracture, surgical site infection, and medical complications, as well as one-year mortality and functional outcomes, were analyzed using the Harris Hip Score. | 12 |

| Bensen 2014 [35] | Dual mobility cup reduces dislocation and reoperation when used to treat displaced femoral neck fractures | Retrospective cohort study | 346 | DM-THA vs. HA | Rate of dislocation, reoperation rate | 18 |

| Rotini 2022 [36] | Is Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty Surgery More Aggressive than Hemiarthroplasty when Treating Femoral Neck Fracture in the Elderly? | Multicentric retrospective study | 302 | HA vs. DM THA | Surgical time, blood loss and transfusion, dislocation rate, mortality, and thromboembolic events | 6 |

| Ukaj 2019 [37] | Dual Mobility Acetabular Cup Versus Hemiarthroplasty in Treatment of Displaced Femoral Neck Fractures in Elderly Patients: Comparative Study and Results at Minimum 3-Year Follow-up. | prospective, comparative interventional single-blinded study | 94 | HA vs. DM THA | Primary outcomes assessed were the rate of postoperative dislocation, Functional Independence Measure (FIM), and Harris Hip Score (HHS). Secondary outcomes included operative time, estimated intraoperative blood loss, time to achieve full weight-bearing post-surgery, time to ambulation with and without crutches, as well as rates of mortality and postoperative infection. | 36 |

| Valcaregni 2022 [38] | Hip fracture reoperation compared with death at two years in elderly patients: lowest risk of revision with dual mobility total hip arthroplasty than with bipolar hemiarthroplasty or internal fixation of Garden I and II. | Retrospective cohort study | 317 | HA vs. DM THA | Mortality rate and reoperation rate | 24 |

| Albanese 2021 [39] | Dual Mobility Articulations in Femoral Neck Fractures: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-analysis of the Outcomes | Meta-analysis | DM THA | postoperative dislocation, revision, and revision surgery rates. | ||

| Tabori Jensen 2018 [40] | Good function and high patient satisfaction at mean 2.8 years after dual mobility THA following femoral neck fracture: a cross-sectional study of 124 patients | Cross-sectional study | 124 | DM THA | Outcome measures included the Oxford Hip Score (OHS), Harris Hip Score (HHS), the EQ-5D for assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and two functional performance tests: the Timed Up and Go (TUG) and the Sit-to-Stand test (10 repetitions). | 2.8 years |

| Canton 2018 [41] | Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty in the Treatment of Femoral Neck Fracture: A Systematic Review of the Literature | Retrospective study | 53 | DM THA | Harris Hip Score (HHS) and the Oxford Hip Score (OHS), radiographic evaluation | 5, 67 years |

| Adam 2012 [42] | Dual mobility cups hip arthroplasty as a treatment for displaced fracture of the femoral neck in the elderly. A prospective, systematic, multicenter study with specific focus on postoperative dislocation | Multicenter prospective study | 214 | DM THA | Rate of dislocation | 9 |

| Uriarte 2021 [43] | Dual mobility cups in total hip arthroplasty after femoral neck fractures: A retrospective study comparing outcomes between cemented and cementless fixation | Retrospective cohort study | 105 | DM THA | Harris Hip Score (HHS) and Merlé D’Aubigné-Postel score (MDP) | 24 |

| Rashed 2018 [44] | Functional Outcome and Health-Related Quality of Life after Dual Mobility Cup total hip replacement for displaced femoral neck fractures in middle-aged Egyptian patients | Case series | 31 | DM THA | Functional evaluation was conducted using the Harris Hip Score (HHS) and the SF-36 questionnaire to assess health-related quality of life (HRQoL), with support from a physiotherapist. | |

| Nich 2016 [45] | Do Dual Mobility Cups Reduce the Risk of Dislocation in Total Hip Arthroplasty for Fractured Neck of Femur in Patients Aged Older Than 75 Years? | Retrospective review | 82 | DMTHA | Complications such as dislocation, intraprosthetic dislocation, reoperation rate, and radiographic evaluation were considered. | 12 |

| Zhang 2021 [46] | Dual Mobility Cup Total Hip Arthroplasty for Displaced Femoral Neck Fractures: A Retrospective Study With a Median Follow-Up of 5 Years | Retrospective review | 112 | DM THA | HHS and main orthopedic complication rate | 60 |

| Darrith 2018 [47] | Outcomes of dual mobility components in total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature | Systematic review | 10,783 | DM THA | The survivorship, along with the rates of aseptic loosening, intraprosthetic dislocation, and extra-articular dislocation in dual mobility THA, were assessed. | 5.4 YEARS |

| Jinnai 2021 [48] | Use of Dual Mobility Acetabular Component and Anterior Approach in Patients With Displaced Femoral Neck Fracture. | Case series | 106 | DM THA | Dislocation rates, perioperative complications, and mortality at 3, 6, and 12 months were evaluated, along with pre- and early postoperative walking ability. Ambulation was classified into four categories: (1) wheelchair-bound (no ambulation), (2) walking with assistance (including elder-specific walkers), (3) walking with a single cane, and (4) independent walking without aids. | 12 |

| Assi 2019 [49] | Mortality Rate and Mid-Term Outcomes of Total Hip Arthroplasty Using Dual Mobility Cups for the Treatment of Femoral Neck Fractures in a Middle Eastern Population | Review | 174 | DM THA | The mortality rate, as well as clinical and functional outcomes, were assessed in a population with specific rituals involving extreme hip positions as part of their daily activities, using the modified Harris Hip Score. | 39.6 ± 13.8 |

| Carulli 2016 [50] | The use of a dual mobility cup in the management of recurrent dislocations of hip hemiarthroplasty. | Retrospective study | 31 | DM THA vs. HA | The aim of this study was to assess the outcomes of revisions using dual mobility cups in unstable hemiarthroplasties. The evaluation was conducted using the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical function score, the Harris Hip Score (HHS), and various radiological criteria. | 3.8 YEARS |

| El-Deeb 2023 [51] | Dual Mobility Cup in Fractures of the Femoral Neck in Neuromuscular Disorders and Cognitive Dysfunction Patients above 60 years old. | Prospective cohort study | 20 | DM THA | Clinical and radiographic outcomes were assessed at the clinic using the Harris Hip Score (HHS) in skeletally mature patients over 60 years old with femoral neck fractures, neuromuscular disorders, and cognitive dysfunction who are candidates for THA. | 24 |

| Zhuang 2022 [52] | Outcomes of dual mobility articulation total hip arthroplasty in ipsilateral residual poliomyelitis. | Retrospective study | 17 | DM THA | Clinical outcomes were assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain score, the Oxford Hip Score, and the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) activity score. Radiographic outcomes were evaluated through radiographs. Complications and reoperations following THA were recorded in patients with residual poliomyelitis who underwent THA with a dual mobility cup. | 77 |

| Henawy 2017 [53] | Dual mobility total hip arthroplasty in hemiplegic patients. | Case series | 24 | DM THA | Clinical results and complication rate in hemiplegic patients treated with DM THA | 12 |

| Bhosale 2024 [54] | Central Fracture Dislocation of the Hip with Ipsilateral Femoral Neck Fracture in an Elderly Patient with Parkinsonism Managed with Dual Mobility Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Case Report and Review of Literature | Case report and review of the literature | 1 | DM THA | Clinical (HHS) and radiological outcomes were evaluated in a patient with a neurological disorder and a neglected post-traumatic central fracture dislocation of the right hip, along with an ipsilateral femoral neck fracture, treated with DM-THA. | 12 |

| Mahajan 2021 [55] | The Neck of Femur Fracture in an Elderly Patient with Schizophrenia and Parkinsonism Managed with Dual Mobility Total Hip Replacement: A Rare Case Report | Case report | 1 | DM THA | Functional outcomes (Harris Hip Score) were evaluated in patients with (1) schizophrenia and parkinsonism, and (2) femoral neck fractures with associated greater trochanter (GT) fractures, managed with total hip replacement using a dual mobility cup and tension band wiring for the GT fracture. | 18 |

| Cnudde 2022 [56] | Total, hemi, or dual mobility arthroplasty for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in patients with neurological disease: analysis of 9638 patients from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register | Longitudinal cohort study | 9638 | DM THA vs. HA vs. THA | The dislocation rate, as well as the revision, reoperation, and mortality rates at one and three years, were recorded. | 12 |

| Saleem 2024 [57] | Arthroplasty treatment options for femoral neck fractures in the elderly: A network meta-analysis of randomized control trials | Meta-analysis | 1490 | DM THA vs. HA vs. THA | Prosthetic dislocation, mortality, operating time, intraoperative blood loss, revision rate, and Harris Hip Score (HHS). | |

| Mufarrih 2021 [58] | Outcomes of total hip arthroplasty using dual mobility cups for femoral neck fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis | Systematic review and meta-analysis | DM THA | Dislocation and mortality rates in patients with femoral neck fractures treated with DM-THA. | 12 |

| Classification | Type/Description | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Garden’s Classification | Type 1: Incomplete and undisplaced | Fracture is incomplete and the femur remains in its original position. |

| Type 2: Complete, undisplaced | Full fracture but no displacement of the femoral head (Figure 1) | |

| Type 3: Partial displacement with misalignment | Partial displacement and misalignment of trabecular bone | |

| Type 4: Completely displaced | Complete displacement of the fracture | |

| Pauwels’ Classification | Type 1: Angle < 30° | Fracture with a stable fracture angle |

| Type 2: Angle between 30 and 50° | Intermediate stability of the fracture angle | |

| Type 3: Angle > 50° | Fracture with high instability due to the large fracture angle |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cicio, C.; Testa, G.; Salvo, G.; Liguori, B.; Vescio, A.; Pavone, V.; Sapienza, M. Femoral Neck Fractures in Elderly Patients: Dual Mobility Cup Arthroplasty or Hemiarthroplasty? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15094844

Cicio C, Testa G, Salvo G, Liguori B, Vescio A, Pavone V, Sapienza M. Femoral Neck Fractures in Elderly Patients: Dual Mobility Cup Arthroplasty or Hemiarthroplasty? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(9):4844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15094844

Chicago/Turabian StyleCicio, Calogero, Gianluca Testa, Giancarlo Salvo, Benedetta Liguori, Andrea Vescio, Vito Pavone, and Marco Sapienza. 2025. "Femoral Neck Fractures in Elderly Patients: Dual Mobility Cup Arthroplasty or Hemiarthroplasty? A Narrative Review of the Literature" Applied Sciences 15, no. 9: 4844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15094844

APA StyleCicio, C., Testa, G., Salvo, G., Liguori, B., Vescio, A., Pavone, V., & Sapienza, M. (2025). Femoral Neck Fractures in Elderly Patients: Dual Mobility Cup Arthroplasty or Hemiarthroplasty? A Narrative Review of the Literature. Applied Sciences, 15(9), 4844. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15094844