1. Introduction

Materials are central to both human perception and artistic expression, yet their influence is often explored primarily from scientific or technical perspectives [

1,

2,

3]. This research seeks to investigate how various materials, whether traditional or contemporary, shape artistic creation and audience reception. By examining how materials are transformed within artistic contexts, we aim to reveal how artists manipulate media to evoke meaning and emotional responses. Furthermore, this study explores how these material transformations open up new creative possibilities for artists, offering opportunities for the continued innovation of artistic practices.

While discussions of materiality in art are abundant, there remains a gap in understanding the intersection between materials and artistic expression from a cross-disciplinary perspective. Traditional forms such as painting and calligraphy are often perceived as distinct from contemporary artistic practices that incorporate a broader range of media. This disconnection prompts a key question: how can these established forms be integrated with everyday art practices to reflect evolving cultural narratives? This study aims to explore this gap by examining how the fusion of traditional and modern materials creates novel avenues for artistic exploration, fostering a deeper connection between art and daily life.

Art represents a confluence of subjectivity and objectivity, where the artist’s personal emotions and thoughts interact with the external world. As Liu’s

Carving Thoughts on the Literary Mind [

4] suggests, the artist “flows with the object and lingers with the mind”. In the process of immersing themself in the world, the artist navigates the myriad phenomena around them, forging connections and contemplating deeply. This engagement results in a synthesis of the artist’s thoughts and emotions, culminating in a creation that reflects the inner significance of their experiences. Through this lens, art becomes not only a product of the artist’s self-awareness but also a conduit for reflecting broader cultural and emotional narratives.

This study contributes to the broader discourse on materiality in art by examining how the transformation of materials can reshape both the creative process and audience engagement. It is crucial to understand that while tangible objects often serve as the primary means through which people engage with the world, the materials underlying these objects are often overlooked. Art, however, invites viewers to engage not only with the visual aspects but also with the materiality itself, offering a deeper understanding of the artwork’s cultural and emotional context [

5,

6,

7].

The preservation and sustainable development of culture are essential for the progress of society, and the role of the arts is as significant as that of science and technology [

8,

9,

10]. Artistic forms serve as powerful tools for cultural exchange, reflection, and innovation. They not only provide opportunities for self-expression but also foster a deeper connection between individuals and the values, experiences, and aspirations of their communities. Art plays a critical role in enhancing aesthetic sensibilities, encouraging viewers to engage with the cultural narratives embedded within works of art.

Contemporary art is increasingly characterized by the integration of diverse materials and media [

11,

12]. This trend promotes greater autonomy and creativity in both form and content, offering artists the freedom to explore new possibilities and break free from traditional constraints. By experimenting with the fusion of various materials and techniques, contemporary artists continue to push the boundaries of innovation, resulting in a rich array of unique and transformative works.

In this context, the research aims to illuminate how material transformations within art influence both the artistic creation process and the viewer’s experience, offering new insights into the evolving role of materials in shaping artistic expression.

This study examines an artist’s pioneering effort to bridge the worlds of ink painting and ceramics, focusing on her process of translating the abstract, spiritual essence of ink painting into the tangible, three-dimensional forms of ceramic art. Ink painting, with its delicate interplay of ink, brushwork, and subtle imagery, reflects deep conceptual and spiritual dimensions that often elude immediate perception, emphasizing fluidity, spontaneity, and an exploration of the unseen. In contrast, ceramic art is grounded in the physical, offering a tactile, 360-degree experience of form and texture, which is inherently more concrete and functional in nature. The artist’s challenge lies in navigating the contrasting technical and aesthetic realms of these two distinct media—ink painting’s emphasis on conceptual expression and ceramics’ focusses on visual and tactile aesthetics—while seeking to create a cohesive and innovative artistic style. This transformation involves not only the technical integration of these mediums but also the conceptual bridging of abstract ideas into physical, sculptural representations. The study delves into the complexities of this artistic journey, analyzing how the artist merges the intangible, spiritual qualities of ink painting with the solid, tactile attributes of ceramics. It examines the nuanced process through which personal painting and calligraphy are reinterpreted and transposed into ceramic forms, revealing both the similarities and tensions between these forms. By exploring the interplay between the two, the study highlights the challenges of harmonizing their divergent characteristics, such as ink painting’s ethereal qualities and ceramic art’s functional emphasis. Ultimately, the study aims to provide a deeper understanding of how these two artistic practices can be integrated, offering insights into the broader implications of combining distinct artistic traditions and media in the pursuit of creative expression.

Specifically, the study addresses the following two key issues:

Expanding artistic boundaries: In the realm of painting and calligraphy, which is confined to two-dimensional space, there is a drive to transcend visual effects and creative media. This study aims to bridge painting and calligraphy with everyday art, aspiring to infuse daily life with pure aesthetics and to make art a pervasive element in everyday experiences.

Exploring medium-specific aesthetics: The study investigates how the distinct characteristics of painting and calligraphy—such as form, materials, pigments, spatial structures, and presentation methods—contrast with those of ceramic craftsmanship. It seeks to uncover how these differences can be harmonized and mutually enhanced, fostering a synthesis between the two artistic traditions.

2. Transformation and Integration of Painting and Calligraphy with Ceramic Art: Creative Ideas and Cognitive Patterns

2.1. The Artist’s Personal Creative Ideas

In the realm of artistic creation, the quest to establish a novel style, distinct from traditional ink painting, requires an exploration of new media and techniques while remaining grounded in the core principles of brush and ink artistry. This pursuit unveils a broad array of possibilities for expressing diverse materials and methods, enabling artists to push the boundaries of conventional practices. The process of redefining artistic style involves a critical engagement with contemporary painting, emphasizing self-awareness and innovation, while striving to cultivate a fresh, globally informed perspective. By integrating conceptual thinking and expressive techniques, the artist’s individuality and artistic vision come to the forefront, allowing the unique synthesis of ideas, mediums, and forms. Artistic style, therefore, emerges through the interaction of conceptual expression, technique, and subject matter, with its true essence realized through the relationship between the mind and the chosen medium [

13,

14,

15,

16]. This dynamic interplay fosters a deeper harmony between perception and cognition, allowing the artist to transcend the limits of mere technical proficiency. In this way, the artist achieves a fluid, intuitive response between the eyes, mind, and spirit, moving beyond the constraints of rational thought to capture the profound essence of their creative vision [

17].

Creation in art is no longer confined to the mere imitation of nature. The objective world is not merely a backdrop for subjective consciousness but a domain to be transcended, where the essence of humanizing nature is sought. Artistic creation represents the synthesis of subjective consciousness and the objective world, awakening latent consciousness and transforming tangible objects into symbols of personal interpretation and emotion. The driving force of aesthetics lies in this internalized integration, where an image evolves into a profound feeling that connects the inner self with the external world. Zhang Yanyuan’s concept of “leaving form and discarding intellect” and Gu Kaizhi’s idea of “wonderful imagination” resonate with this notion [

18,

19]. Here, intellect refers to cognitive functions such as memory, imagination, and judgment, which are pivotal in creation. The focus shifts from a detailed depiction to reflecting on the image’s memory and imagination, emphasizing intuitive understanding and immersive experience. This pursuit aims to uncover the essence behind phenomena, achieving a process of concentration and abstraction. Thus, painting becomes an external manifestation of the artist’s inner spiritual realm, conveying authentic emotions. All experiences and expressions in painting are rooted in the mind and emotions, with spiritual resonance evident throughout the creative process.

This research case study centers on natural landscapes, using these as a basis to refine artistic sentiment. By abstracting the characteristics of brush and ink, the study aims to align artistic expression with spiritual depth. This approach seeks to elevate the work to a transcendent level in terms of composition, structure, expression, and intention. The creative principles distilled from this study are as follows:

2.1.1. Embracing the Essence of Creation

The creator underscores the interconnectedness between subjective aesthetic experience and introspective concepts, prioritizing essence over form and spirituality over materiality. The pursuit of aesthetic balance involves finding a delicate equilibrium between resemblance and abstraction. The goal is to achieve harmony between humanity and nature, embodying both natural and personal essence through a language that fuses concreteness with abstraction. This synthesis creates an artistic conception that straddles the line between resemblance and non-resemblance.

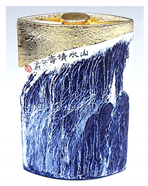

The purpose of artistic creation is to remain true to the personal understanding of one’s own nature, and the creation seeks to express subjective and inner feelings, portraying all natural elements through inner emotions. It is the result of the generation and regeneration of the soul. Observing the waterfall by the riverside, listening to the sound of waves beneath the pine trees, sitting and watching the clouds rise, the artist pours their passion into the mountains and rivers, depicting the vitality of all things and unifying creation with the source of the heart. Although it may appear as sketching from life, it is not a strict representation of reality. What is more, while it may seem like painting scenery, it is not a mere portrayal of the external landscape. It is the embodiment of the principle that the mind gives birth to infinite phenomena and the spirit breathes life into all things. The heart and the object, form and spirit, emptiness and substance, and resemblance and non-resemblance are intertwined. Painting is not about depicting the exact likeness of reality or capturing the specific scene. It is about capturing the resemblance of the spirit and the naturalness of the sentiment. It is precisely through the brushwork that the spirit is subtly conveyed, transcending the literal form. Abandoning the pursuit of strict resemblance, it strives for the resemblance within non-resemblance, reaching a state of transformation. As the saying goes, when inspiration arises, the spirit transcends rationality, and when inspiration subsides, the achieved intention surpasses the image. This can be seen in

Figure 1.

2.1.2. Emphasizing Harmony and Rhythm

The Vitality of Qi has been the highest guiding principle pursued by artists in China for thousands of years. Qi is the essence of life. If a painting lacks vitality, it is like observing a lifeless specimen. How can it move people? Rhythm represents harmony. A harmonious composition delights and uplifts the spirit. The rhythm of ink and wash captures the essence of the intangible, portraying the vastness of mountains, rivers, and the earth. Through painting, true emotions are revealed. The focus is on a clear, ethereal, and distant orientation, where all things are perceived through enlightenment and observed to understand the essence of mountains, rivers, and objects. The artist transforms the objects into mental images on the canvas, reflecting the inner spiritual realm. Through perception and the pursuit of essence, the artist translates their thoughts into form, allowing the creative process to become a declaration of spiritual freedom. This integration of self and self-contentment leads to a return to the true essence in the structure of the artwork, encompassing the ultimate care for life (see

Figure 2). German philosopher Kant proposed the following: When the mind reflects on the beauty of nature, it cannot help but find itself interested in nature as well, and through symbols, nature, in its beautiful forms, symbolically communicates with us [

20].

The creation of landscape painting involves the artist immersing themself in the exploration of various places, accumulating impressions and insights from nature. The artist refines and purifies the impressions and feelings in their mind, extracting the true essence from the false, transforming this process into one of devotion and understanding. When the artistic imagery becomes deeply ingrained, the artist takes up the brush, allowing their emotions to guide their hand and mind, striving to create lively artistic images that are natural yet surpass reality (also see

Figure 2).

2.1.3. Inspired by the Journey of the Mind

Form follows function, and function follows the Way. The artistic realm is born from the journey of the mind, transcending beyond mere representation. Thus, in painting, simplicity and ease are sought, not for exact likeness but for a profound sense of rhythm. Every blade of grass, every hill and valley, all originate from the unique realm of imagination, something beyond the earthly realm, evoking a dreamlike feeling that symbolizes different states of mind. The formation of the artistic composition stems from the intangible, and the recognition of form does not adhere to physicality. It encompasses the interplay of dynamics and stillness, showing the connection between the visible and the invisible. This characteristic embodies the essence of tranquility within etherealness, and the essence of etherealness within tranquility. Etherealness arises from emptiness, and tranquility arises from stillness, harmoniously merging with all phenomena in nature. Although the wind in the natural world varies, it arises naturally, without intention. On the other hand, human language is a product of the mind. In this series of work, the artist creates a unique and extraordinary realm beyond the confines of heaven and earth, expressing a personal ideal earthly paradise. It emphasizes the pure beauty that transcends ordinary life, not solely relying on the play of imagination with brush and ink. It allows the interest in landscapes to return to the natural and innocent, expressing personal aesthetic tastes, thoughts, and emotions (see

Figure 3). Hegel proposed the following: In terms of its spatial existence, the subjectivity of painting is just a manifestation of the inner spirit. Art expresses it for the spiritual community. In painting, its content is subjectivity and, at the same time, the inner life itself that has undergone specific concretization.

2.2. Differences and Similarities Between Painting and Ceramics: Artists’ Physical, Material, and Spiritual Dimensions

Building upon the previous section, the research team further analyzed, through communication and discussions with the artist, the changes and differences in the artist’s physical, material, and spiritual aspects when facing the transformation from painting to ceramics. It should be noted that these contents may be subjective, but from another perspective, they depict the artist’s truest concepts, which may also inspire other artists to some extent.

In terms of physical differences, in the field of painting, due to the use of complex materials, large acrylic boards are required as a base, necessitating a spacious and independent working space. The process of painting involves constantly tilting and adjusting the acrylic board from various angles, requiring prolonged standing and physical adjustments. On the other hand, in the field of ceramic art, due to the use of different materials and the complex production process, large clay bodies are used as a base, also requiring a spacious and independent working space. Artists often find themselves in a high-temperature environment of around 40 degrees Celsius. The process of ceramic art creation involves tilting and adjusting the clay bodies from various angles, requiring prolonged standing and specific postures, thus consuming a significant amount of physical energy.

In the realm of pure artistry in painting, due to the limitations of two-dimensional space, artists strive to break through the visual effects and explore the connection between painting and the art of everyday life. They aim to bring pure aesthetics into daily life while making art omnipresent in life.

The core of painting lies in the artist’s ability to transcend the visual realm and express their inner thoughts and emotions through brushwork. It represents a sublime state of freely following one’s heart that allows thoughts to wander without constraint, leading to the recreation of a certain artistic conception. Ceramic art, on the other hand, is rooted in the choice of materials and emphasizes the transformation of artistic spirit. It not only pursues exquisite craftsmanship but also embodies the artist’s absolute control and mastery of materials and creative thinking. It integrates artistic elements into ceramics, transforming them into works of art.

The claim that material transformation enhances the artistic experience can be supported through real-world applications in various art forms, where altering the materials enriches both the sensory and intellectual engagement of the viewer, as seen in the following, specifically:

Sculpture and installation art: Artists like Picasso (1881–1973) and Duchamp (1887–1968) demonstrate that transforming everyday objects or materials into art challenges traditional concepts and invites deeper intellectual engagement. Picasso’s assemblages and Duchamp’s readymades force viewers to reconsider the relationship between object, meaning, and context.

Textile arts and fashion: Designers such as Issey Miyake (1938–2022) use material manipulation—like pleating—to explore the relationship between fabric and the human body, creating an immersive, interactive experience that extends beyond visual aesthetics. Similarly, artists like Anni Albers (1899–1994) manipulate textile materials to produce intricate, tactile works that invite both sensory and intellectual contemplation.

Digital and generative art: In digital art, the transformation of code and data creates dynamic, interactive works that respond to the viewer in real-time, adding layers of motion and interactivity that enhance the experience. The constant transformation of digital materials in AI-generated art, for example, deepens viewer engagement by emphasizing process alongside form.

Architecture and environmental art: Architects like Frank Gehry (1929–) use material transformation to create visually striking structures that engage viewers on both an emotional and intellectual level. Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao exemplifies how the manipulation of materials such as titanium can evoke a sense of movement and fluidity, enhancing the viewer’s experience. Environmental artists like Andy Goldsworthy (1956-) use the transformation of natural materials to engage viewers in contemplation about nature, time, and impermanence.

In short, material transformation elevates the artistic experience by altering the way the viewer engages with the work, whether through intellectual stimulation, sensory immersion, or emotional resonance. This transformation is not merely cosmetic; it deepens the viewer’s connection to the art.

2.3. From Creation to Appreciation: Cognitive Model of Artwork Transformation

From the perspective of communication theory, the artistic creation process of expressing artistic conception and emotional context can be seen as encoding, while the audience’s understanding and interpretation of artwork can be seen as decoding. The artist is the sender, and the audience is the receiver [

1,

21,

22,

23]. The cognitive process of artwork transformation involves three levels: the technical level (Did you see that?), the semantic level (Did you understand?), and the affective level (Are you Touched?). Firstly, the audience perceives the visual representation at the technical level, followed by understanding the meaning and connotation at the semantic level, and finally achieving emotional resonance at the affective level [

24,

25]. These three levels correspond to the artist’s artistic creation process, which is encoded through the creative concepts of (1) creation into your heart, (2) rhythm as the essence, and (3) inspired by the mind.

The decoding process for the audience involves the following: (1) whether the audience can perceive and form sensory impressions of the artwork’s visual form; (2) whether the audience can comprehend and engage in the cognitive process of extracting meaning from the artwork; and (3) whether the audience can be deeply moved and experience internal emotions triggered by the artwork [

24].

In other words, for the audience, the process of appreciating and understanding the artwork unfolds through three stages: capturing attention (identification), achieving accurate cognition (understanding), and experiencing profound emotions (reflection). The cognitive model of transformation for artworks, as depicted in

Figure 4 [

24,

25,

26], involves identification as situational perception, indicating whether the artwork can attract the audience; understanding as aesthetic cognition, indicating whether the audience can comprehend the informational meaning; and reflection as a psychological response, indicating whether the audience can be deeply moved by the artwork.

From the perspective of cognitive ergonomics,

Figure 4 also aligns with Norman’s three-level model of design concepts: the design level [

27], the user level, and the system level, representing the artist’s mode of thinking, the audience’s cognitive mode, and the artwork itself, respectively. Norman [

28] further pointed out the three levels of the design process: the visceral level, the behavioral level, and the reflective level, which correspond to the audience’s aesthetic experience, meaning experience, and emotional experience. This explains the change in the audience’s cognitive mode during the communication process depicted in

Figure 4. It also delves into the audience’s cognitive process, explaining how they perceive the external form and emotional implications of the artwork, in order to help artists create artworks that possess shared experiential mental models using familiar symbols understood by the audience [

24,

25,

26].

To create an effective cognitive model of artwork transformation, it is necessary to address the three levels of cognition depicted in

Figure 4: technical, semantic, and affective. A successful communication process ensures that the audience completes the decoding process, with two dimensions: horizontal and vertical. The horizontal dimension involves the progression from situational perception to experiential meaning, while the vertical dimension represents the deepening process from external to internal, collectively constructing the cognitive model of artwork transformation.

3. Materials and Methods

The artist whose works we selected for this study is a painter who also teaches at a university. We met her while she was pursuing her doctoral degree. We were immediately intrigued by her work, and when we learned that she not only paints Chinese ink paintings but also creates ceramics, we became curious about her ability to navigate these two different fields. We were particularly interested in how the use of materials with different physical properties in artistic creation can yield vastly different results, and how the artist manages to excel in both domains. While answers to these questions may not be fully realized right away, they could potentially offer the artist more diverse creative avenues. Regarding the use of polarized adjectives, we invited several university professors engaged in aesthetic research and art creation, as well as students currently pursuing master’s and doctoral degrees in art and design, to engage in a collective discussion. We found that using polarized adjectives to construct an evaluation system might be a novel approach. If material science is based on rationality, then the emotional aspect of art creation can be assessed and analyzed in ways different from traditional methods.

3.1. Construction of Evaluation Attributes for the Transformation of Painting to Ceramic Art

Using the cognitive model of artwork transformation and experience depicted in

Figure 4 as the research framework, this study explores how artists transform their paintings into ceramic artworks and investigates how the general audience understands and perceives the artists’ creative concepts, aiming to comprehend the essence of artwork transformation [

24,

25,

26]. By integrating concepts from communication theory, cognitive theory, and aesthetic experience through literature review, and combining the differences between painting and ceramic art presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, this study further constructs a set of polarized adjective attributes as evaluation criteria. Specifically, these attributes consist of 9 groups: A1 (Two-dimensional Composition ↔ Three-dimensional Form); A2 (Subjective Introspection ↔ Objective Intuition); A3 (Rendering Expansion ↔ Internal Absorption); A4 (Free Expression ↔ Symbolic Transformation); A5 (Discernible Brushstrokes ↔ Indistinct Shades); A6 (Profound Epiphany ↔ Superficial Observation); A7 (Personal Techniques ↔ Creative Transformation); A8 (Single Perspective ↔ Multiple Perspectives); and A9 (Spiritual Conception ↔ Pure Aesthetic Sense). Based on existing research [

29,

30,

31], the proposed cognitive model of artwork transformation and experience in this paper can serve as cognitive and evaluative criteria for assessing the transformation of painting artworks into ceramic art.

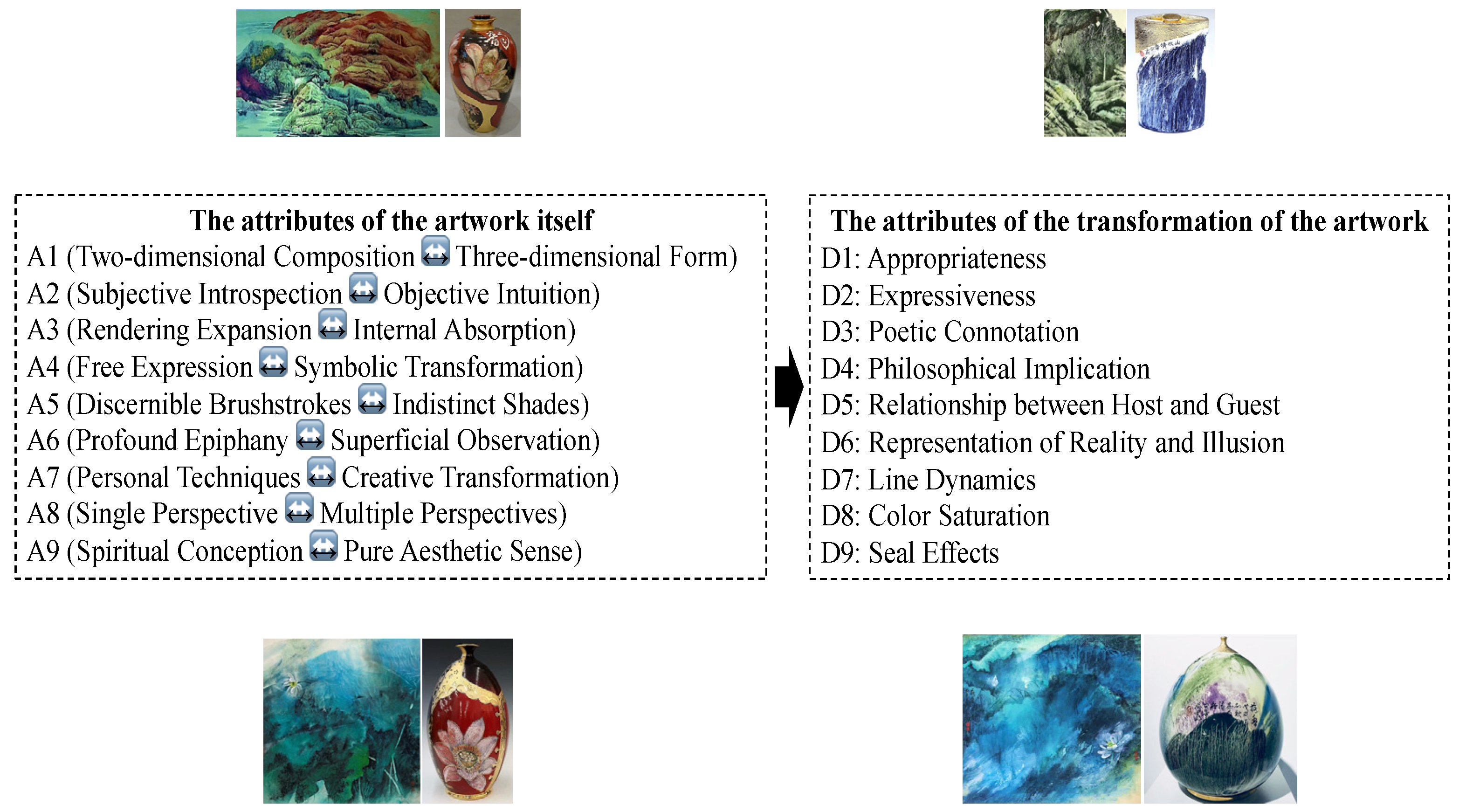

To better grasp the audience’s perspectives, this study proposes a two-stage evaluation approach (see

Figure 5): the first stage involves the individual evaluation of each artwork using polarized adjective attributes to explore the creative attributes of individual artworks. The second stage involves the evaluation of paired artworks, where paintings are transformed into ceramic art, assessing the appropriateness of the transformation. This evaluation includes criteria such as Appropriateness (D1), Expressiveness (D2), Poetic Connotation (D3), Philosophical Implication (D4), Relationship between Host and Guest (D5), Representation of Reality and Illusion (D6), Line Dynamics (D7), Color Saturation (D8), and Seal Effects (D9). The transformation relationships are depicted in

Figure 5, while the polarized adjective attributes for individual artwork evaluation are presented in

Table 1, and the evaluation attributes for the appropriateness of transformation are shown in

Table 2.

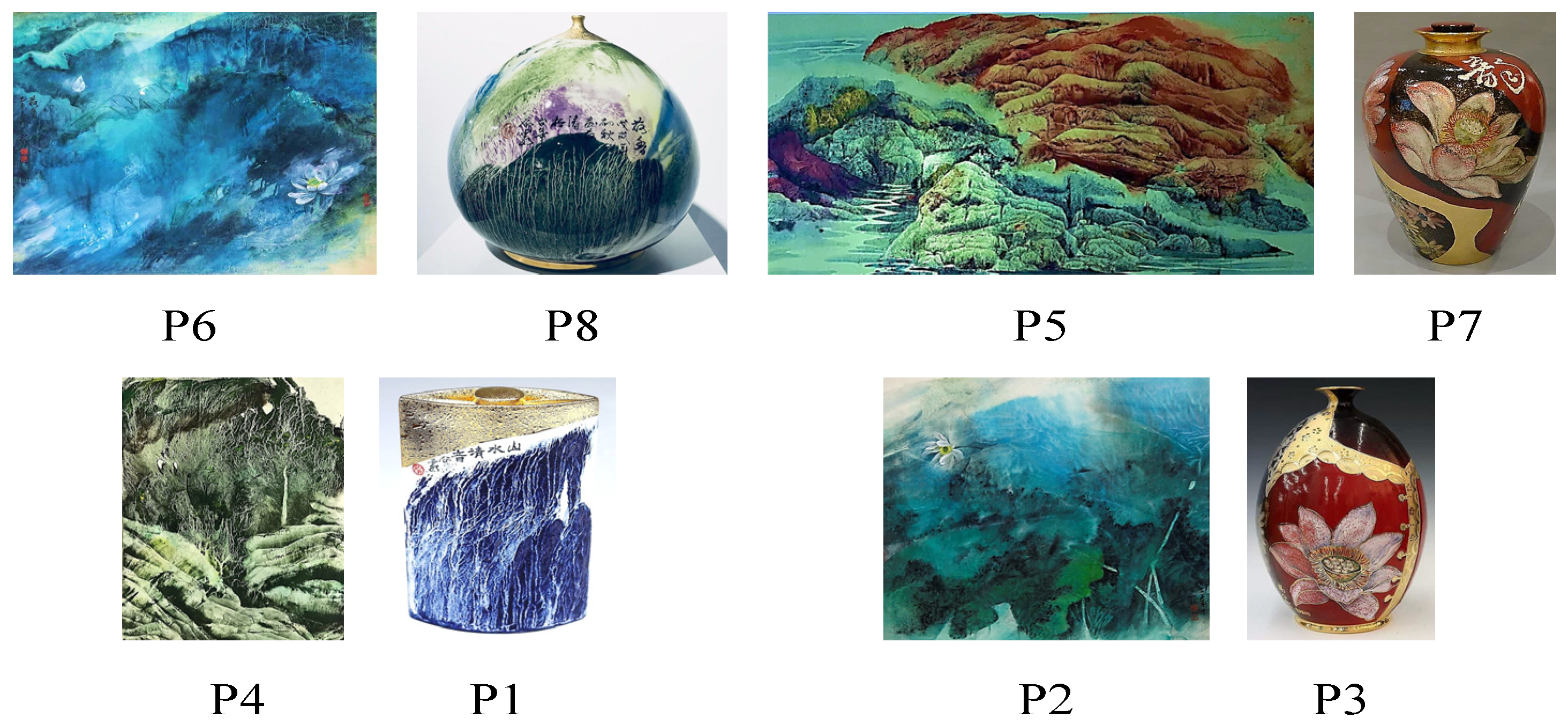

3.2. Samples

The research samples consist of 4 pairs of artworks (8 pieces in total) created by artists based on the concepts of nature within, rhythm as the essence, and inspired by the mind to transform painting art into ceramic art, as shown in

Figure 6. The selection of painting artworks considers different styles of creation, such as expressiveness, poetic connotation, philosophical implication, the relationship between host and guest, the representation of reality and illusion, line dynamics, color saturation, and seal effects. The selection of ceramic art considers elements of three-dimensional form, objective intuition, internal absorption, symbolic transformation, superficial observation, creative transformation, multiple perspectives, and pure aesthetic sense.

3.3. Participants and Evaluation Procedure

This study employed an online questionnaire survey, collecting a total of 403 responses, with 389 valid questionnaires. Among the participants, there were 107 males (27.5%) and 282 females (72.5%). The age groups were divided as follows: 17 participants were under 20 years old (4.4%), 38 participants were aged 21–40 (9.8%), 225 participants were aged 41–60 (57.8%), and 109 participants were aged over 61 (28%). In terms of education, there were 127 participants with graduate degrees (32.6%), 176 participants with undergraduate degrees (45.3%), and 86 participants with other educational backgrounds (22.1%). Regarding academic disciplines, 213 participants were from art-related fields (54.8%), 38 participants were from design-related fields (9.8%), and 138 participants were from other fields (35.4%).

Firstly, participants were asked to subjectively assess their understanding of the creative concepts for the 8 artworks based on the polarized adjective attributes in

Table 1. These attributes were derived from the differences between painting and ceramic art presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 and transformed into evaluation criteria, as depicted in the middle section of

Figure 4. Next, participants evaluated the appropriateness of the transformation for the 4 pairs of paintings transformed into ceramic art, using the questionnaire format shown in

Table 2 above. After completing the evaluation, participants were then asked to indicate their favorite pair of artworks.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of Polarized Adjective Attributes for Individual Artworks

Table 3 presents the mean and standard deviation of the 9 polarized attribute evaluations for the 8 artworks by all participants. For example, the average score for attribute A1 two-dimensional composition and its standard deviation for artwork P1 are 3.681 and 1.307, respectively. Similarly, for attribute A9 and its standard deviation, the values are 2.692 and 1.348, respectively, for artwork P8. The reliability coefficient is 0.947, which is higher than 0.9, indicating a high level of data reliability.

The analysis of item-to-total correlation coefficients reveals that all CITC values are higher than 0.1, indicating good interrelatedness and reliability among the items. In summary, the high reliability coefficient of the research data, exceeding 0.9, indicates high data reliability for further analysis and discussion.

Regarding the differences in the polarized adjective attribute evaluations between male and female participants,

Table 4 provides a comparison. Specifically, the following was discovered:

For artwork 3, in terms of attribute A3 (Rendering expansion ↔ Inward absorption), there is a significant difference at a significant level (t = −2.77, p < 0.01), indicating that the average score of female participants (3.79) is significantly higher than that of male participants (3.60). Similarly, for artwork 8, in terms of attribute A3 (Rendering expansion ↔ Inward absorption), there is a significant difference at a significant level (t = −2.01, p < 0.05), with the average score of female participants (2.89) being significantly higher than that of male participants (2.56).

For artwork 8, in terms of attribute A4 (Freedom of expression ↔ Symbol transformation), there is a significant difference at a significant level (t = −2.24, p < 0.05), with the average score of female participants (2.87) being significantly higher than that of male participants (2.51). However, there were no significant differences observed between male and female participants in the other artworks and attributes.

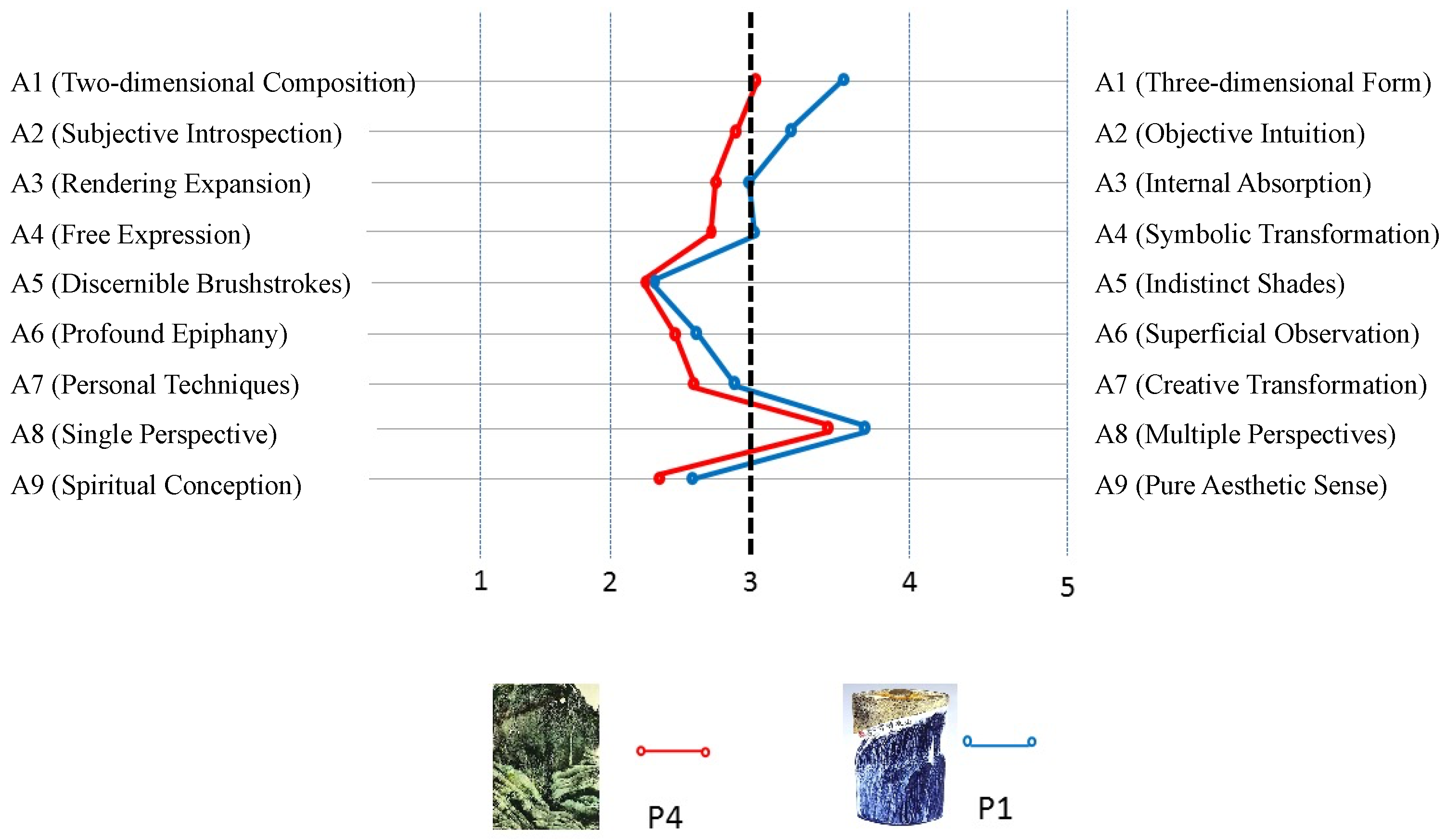

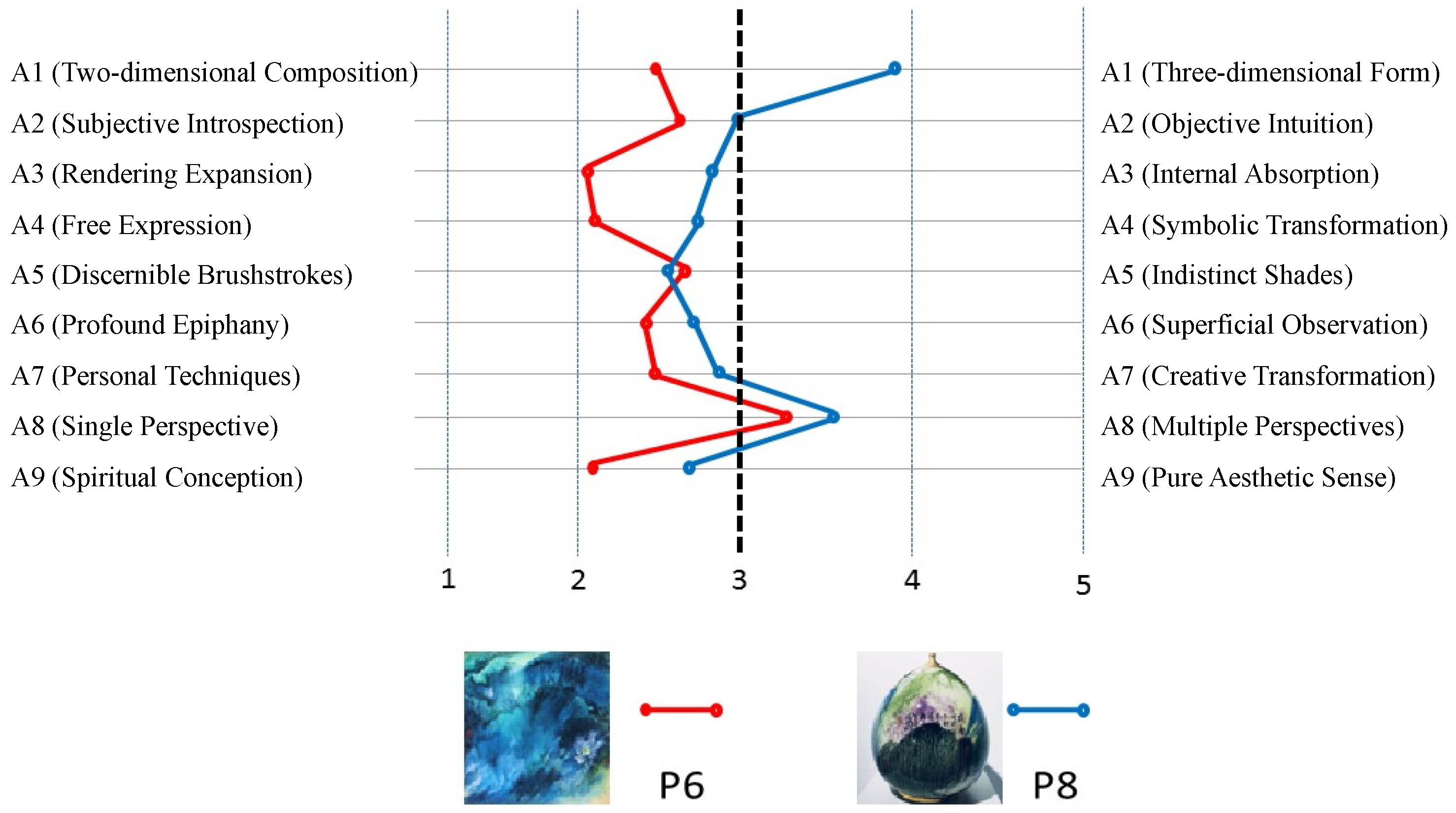

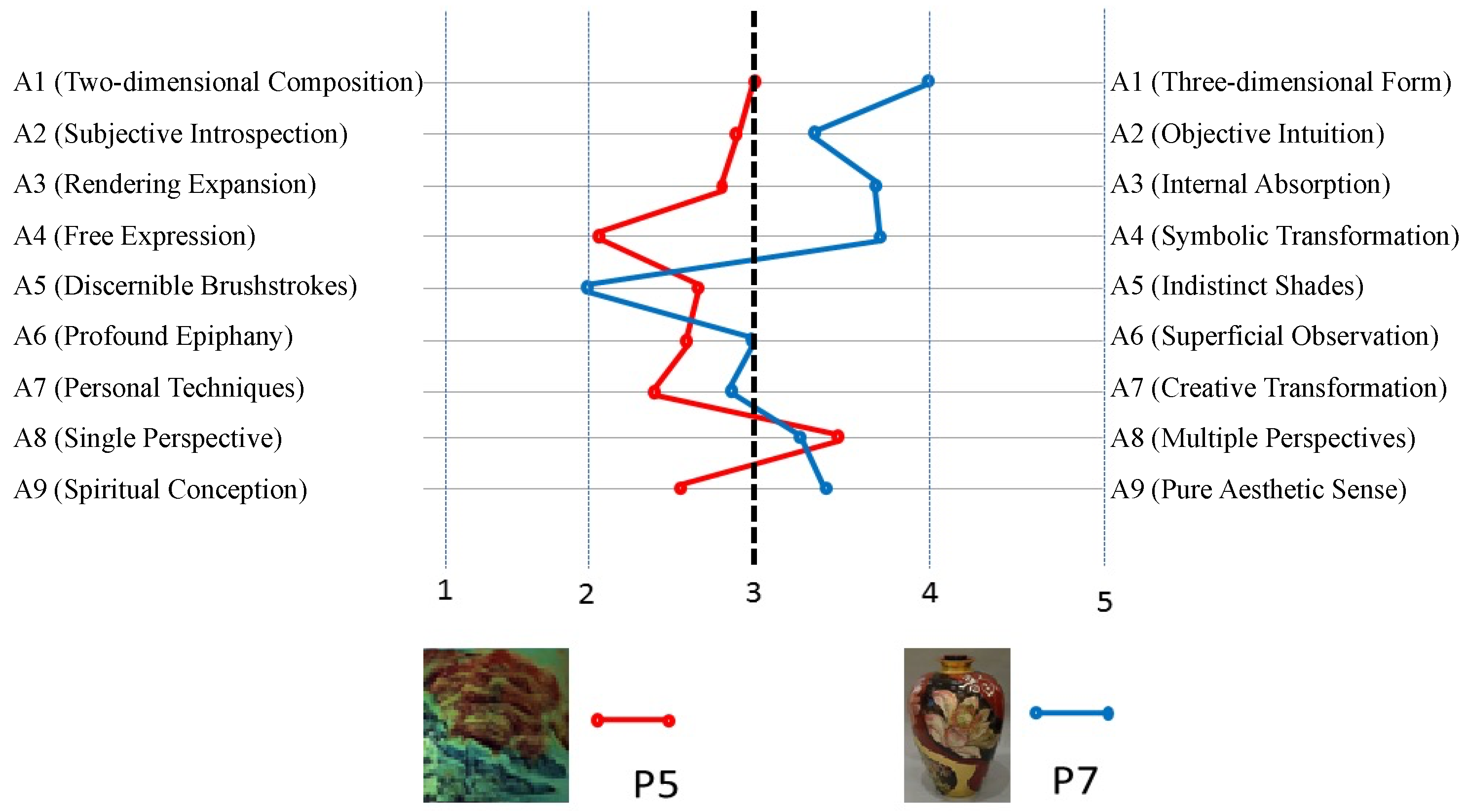

Based on the evaluation of the polarized adjective attributes for the 8 artworks in this case study, participants were able to discern the differences between painting and ceramic art. In the comparison between the paired painting artwork (P4) and ceramic art (P1), apart from the attribute A8 (Single perspective ↔ Multiple perspectives) showing significant differences, there were no significant differences observed for the other attributes. The comparison of polarized adjective attribute evaluations in

Figure 7 indicates no trend towards polarization, suggesting that except for the attribute (A8), there were no differences in the evaluation of other attributes in the process of transforming from painting artwork (P4) to ceramic art (P1).

4.2. Comparison of Attribute Evaluations for Artwork Transformation Pairings

Table 5 shows the average scores and standard deviations of the 9 evaluation attributes for the 4 pairs of artwork transformations by all viewers. For example, for pairing C1, which involves the transformation of painting artwork P5 into ceramic art P7, the average score for attribute D1 is 3.551, with a standard deviation of 1.216. Similarly, for pairing C4, which involves the transformation of painting artwork P6 into ceramic art P8, the average score for attribute D3 is 4.008, with a standard deviation of 0.999, while the average score for attribute D8 is 4.11, with a standard deviation of 0.894.

Regarding the participants’ age, the analysis of differences in the independent variable of painting and ceramic pairing characteristics by age is presented in

Table 6. Specifically, the following was found:

For pairing C3, there are significant differences among different age groups in the evaluation of attributes such as D1, D2, D7, and D8. At a significant level (p < 0.05), the evaluation of attribute D1, D7, and D8 for pairing C3 shows significant differences among the following age groups: 61 years and above > 41–60 years > 21–40 years > 20 years and below.

For pairing C3, there is also a significant difference in the evaluation of attribute D2 at a significant level (

p < 0.01). Detailed information can be found in

Table 6.

Table 6.

Analysis of differences in painting and ceramic pairing characteristics by age.

Table 6.

Analysis of differences in painting and ceramic pairing characteristics by age.

| Artworks | Evaluation Criteria | Source of Variation | SS | DF | MS | F | Post-Hoc Tests |

|---|

![Applsci 15 04175 i003]()

C3 | D1 | Between Groups

Within Groups

Total | 13.361

468.586

481.946 | 3

350

353 | 4.454

1.339 | 3.327 * | 4 > 3 > 1 > 2 |

| D2 | Between Groups

Within Groups

Total | 14.354

440.349

454.703 | 3

350

353 | 4.785

1.258 | 3.803 ** | 4 > 3 > 1 > 2 |

| D7 | Between Groups

Within Groups

Total | 9.362

406.559

415.921 | 3

350

353 | 3.121

1.162 | 2.686 * | 4 > 3 > 1 > 2 |

| D8 | Between Groups

Within Groups

Total | 7.425

281.278

288.703 | 3

350

353 | 2.475

0.804 | 3.080 * | 4 > 3 > 1 > 2 |

![Applsci 15 04175 i004]()

C4 | D8 | Between Groups

Within Groups

Total | 6.290

276.414

282.703 | 3

350

353 | 2.097

0.790 | 2.655 * | 4 > 3 > 1 > 2 |

Apart from these findings, there were no significant differences observed among participants of different ages in relation to the other artworks and attributes. The results of this study indicate that as age increases, participants are better able to perceive the differences in the transformation of painting artworks into ceramic art.

Regarding the participants’ education level, the analysis of differences in the independent variable of painting and ceramic pairing characteristics by education level is presented in

Table 7. Specifically, the following was found:

For pairing C1, there are significant differences among different education levels in the evaluation of attributes such as D1 and D7; for pairing C3, there are significant differences in the evaluation of attributes D1 and D3; and for pairing C4, there is a significant difference in the evaluation of attribute D9. At a significant level (p < 0.05), for pairings C1 and C3, significant differences in the evaluation of attributes D1, D3, and D7 were observed among participants with different education levels: Other education > Graduate level.

For pairing C4, there is a significant difference in the evaluation of attribute D9 at a significant level (p < 0.05): College level > Graduate level.

Table 7.

Analysis of differences in painting and ceramic pairing characteristics by education level (ANOVA).

Apart from these findings, there were no significant differences observed among participants of different education levels in relation to the other artworks and attributes. The results of this study indicate that education level is not a major factor in perceiving the differences in the transformation of painting artworks into ceramic art.

Regarding the participants’ professional background, the analysis of differences among viewers with different professional backgrounds is presented in

Table 8, as follows:

For pairings C1–C4, there are significant differences in various evaluation attributes. For example, pairing C1 shows significant differences in attributes such as D2, D3, and D5; pairing C2 shows significant differences in attributes such as D1, D2, and D8; pairing C3 shows significant differences in attributes such as D1, D2, D4, D5, and D8; and pairing C4 shows a significant difference in attribute D1 at a significant level (p < 0.05) among participants with different professional backgrounds.

The degree of differences varied among the attributes. For example, pairing C1 shows significant differences at a significant level (p < 0.01) in the evaluation of attribute D2 based on professional background: Art-related > Design-related. At a significant level (p < 0.05), in the evaluation of attribute D3, the results show differences in professional background: Art-related > Other > Design-related. Similarly, in the evaluation of attribute D5, the results show differences in professional background: Art-related > Design-related > Other.

Table 8.

Analysis of differences in painting and ceramic pairing characteristics by professional background.

Apart from these findings, there were no significant differences observed among participants with different professional backgrounds in relation to the other pairings and attributes. The results of this study indicate that viewers with an art-related background outperform those with a design-related or other disciplinary background in perceiving the differences in the transformation of painting artworks into ceramic art. Among the other disciplines, performance is superior to that of the design-related background, which may be attributed to the stronger engineering background of design-related disciplines, which tend to have a more rational evaluation. The actual reasons behind these differences between sensibility and rationality warrant further investigation.

4.3. Discussion

Regarding the preference of all participants for the question “Which of the following artwork transformations do you like the most?”, the results are shown in

Figure 8.

Pairing C2 received the highest number of votes (209 people/53.7%), followed by pairing C3 with 92 people (23.7%) in agreement. Pairing C1 was chosen by 78 people (20.1%), while pairing C4 received the lowest preference, with only 49 people (12.6%) liking it. Referring to the data in

Table 5, the average scores of C2 for all evaluation attributes were significantly higher than the other three pairings based on paired

t-tests (

t = 3.17,

p < 0.01). Pairings C1 and C3 showed no significant difference based on paired

t-tests but were both significantly better than the fourth pairing (t = 3.09,

p < 0.01).

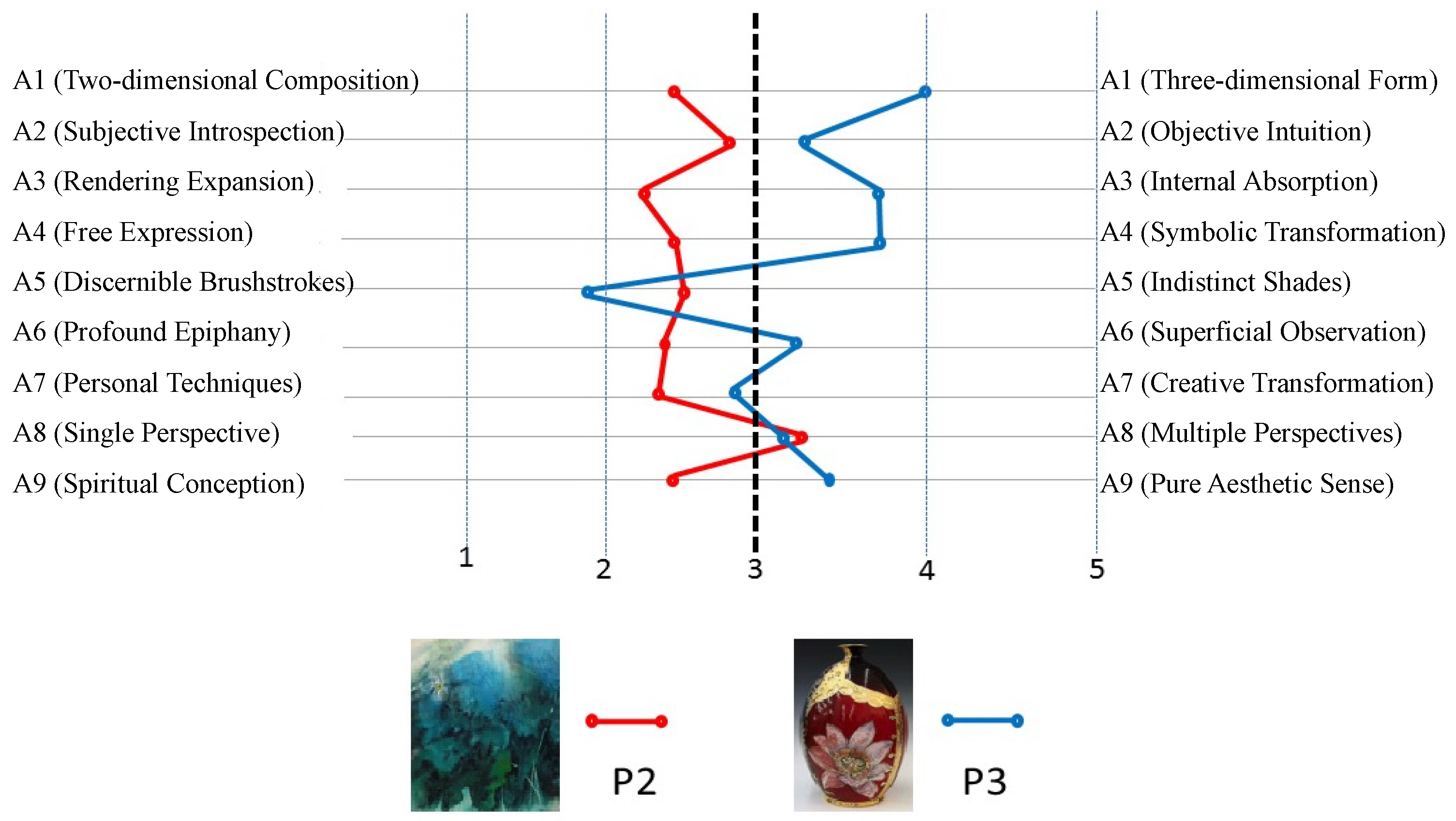

By examining the scores of individual artworks in the polarized adjective attributes in

Table 3, as well as

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, it can be seen that the proposed two-stage polarized adjective evaluation effectively distinguishes the cognitive process of transforming painting artworks into ceramic art.

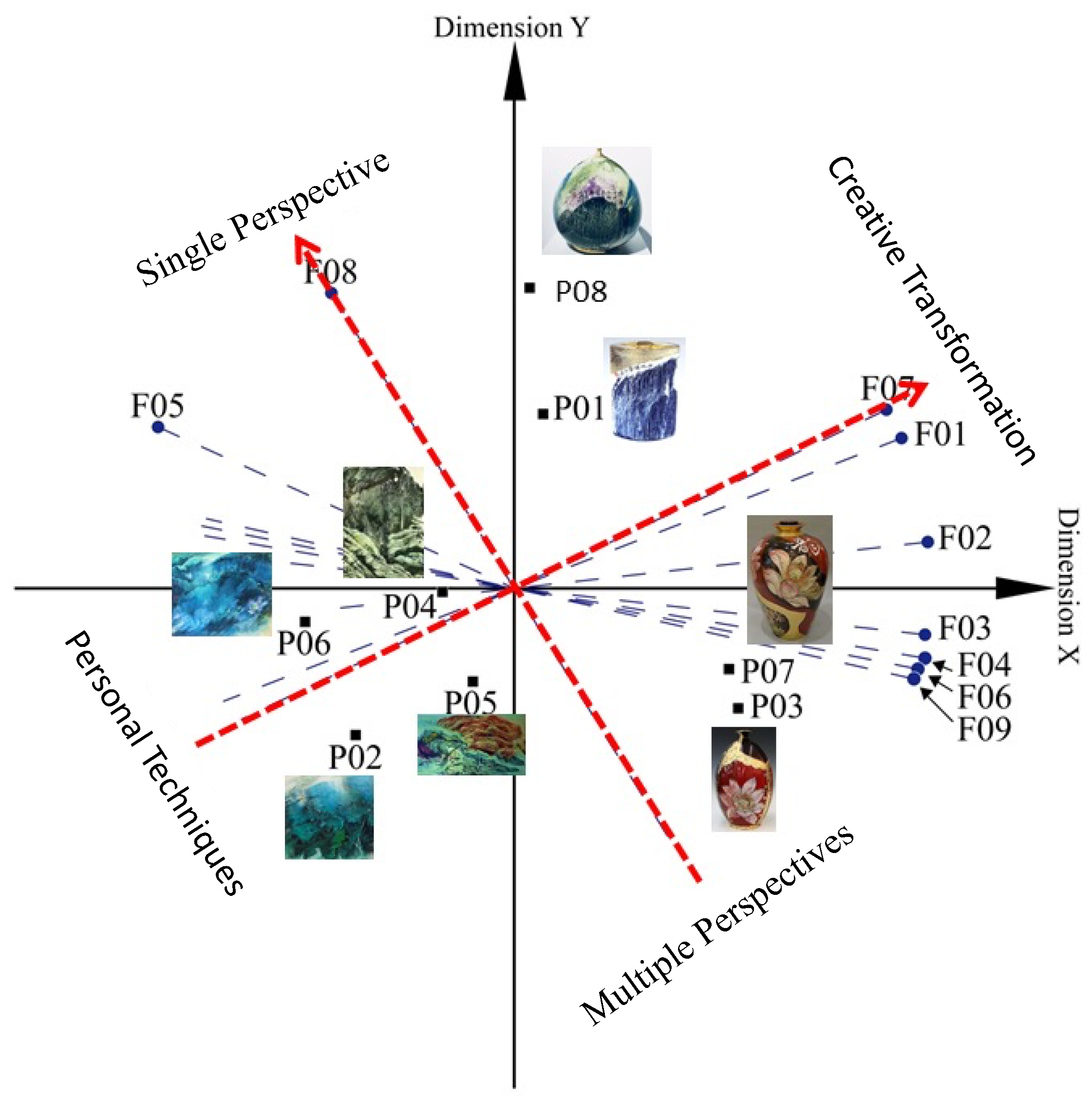

Furthermore, using the data from

Table 3, the study employed the Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) method to construct a two-dimensional cognitive space relationship map. The two dimensions are Dimension 1: A7 (depiction of nature ↔ dynamic transformation) and Dimension 2: A8 (single perspective ↔ multiple perspectives), as shown in

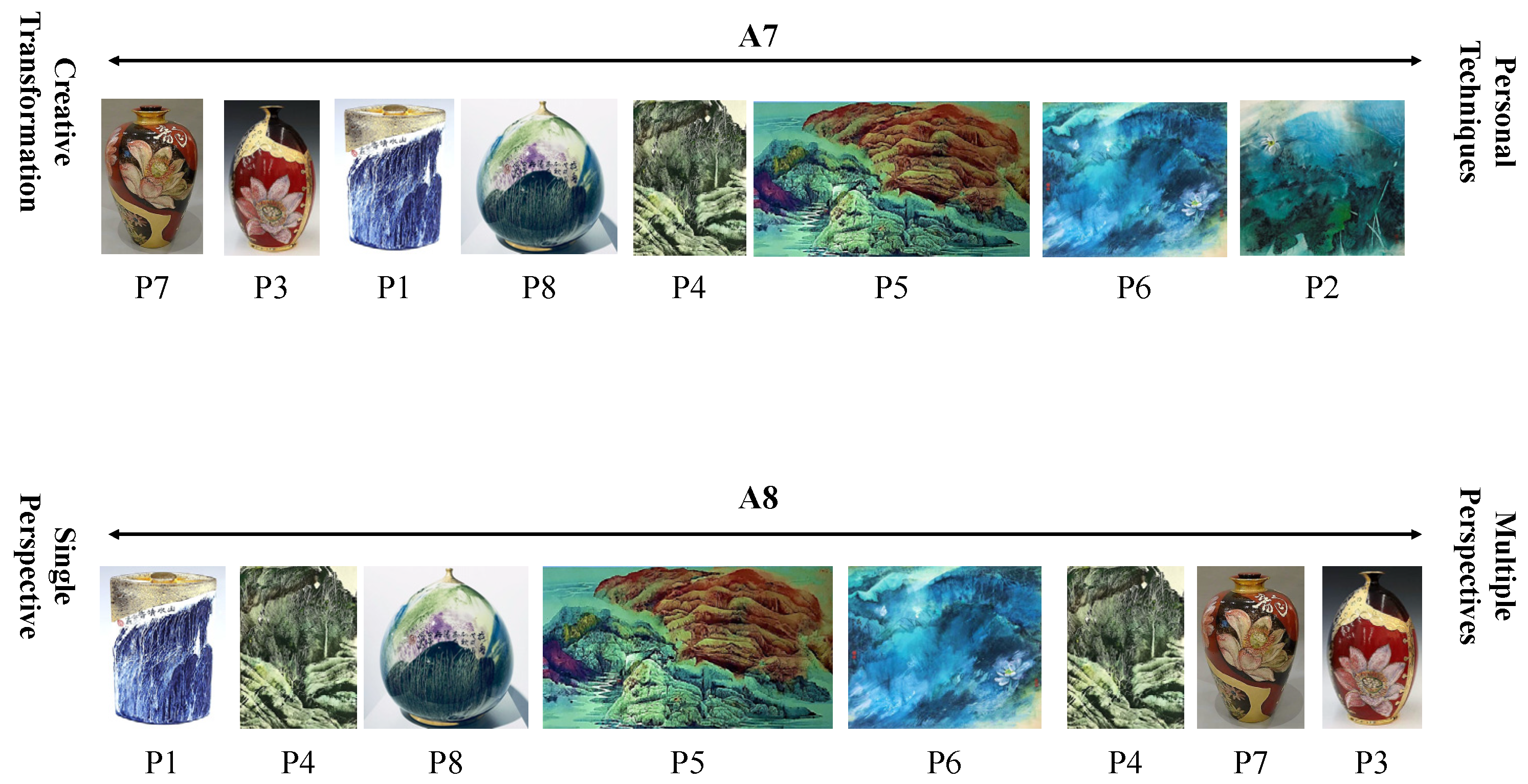

Figure 12. Dimension 1 explains 89.33% of the variance, while Dimension 2 explains 7.69% of the variance, resulting in a total explained variance of 97.02%.

From

Figure 12, it can be observed that the painting artworks and ceramic art are distributed on opposite sides of Dimension 1: A7 (Depiction of Nature ↔ Dynamic Transformation), as depicted in the sorting graph shown in

Figure 13. This indicates that participants were able to distinguish the cognitive differences between painting creation and ceramic art in this study. Examining the sorting graph for Dimension 2: A8 (Single Perspective ↔ Multiple Perspectives), it can be seen that participants had a polarized view of the single perspective and multiple perspectives in ceramic art, as well as a polarized trend in painting artworks. One possible reason could be that compared to P1 and P7 as well as P3, which are all cylindrical in shape, the continuous patterns in P7 and P3 can trigger participants’ imagination. The underlying reasons behind this phenomenon warrant further investigation.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

In the realm of traditional painting and calligraphy art, artists have long sought to break free from the constraints of two-dimensional space and connect painting creation with the art of daily life. They aim to bring pure aesthetics into life, making art ubiquitous in our daily routines. Artistic aesthetics showcase personal taste and style, manifesting in various forms of aesthetic expression in our food, clothing, housing, transportation, and leisure activities. Without the need for profound philosophical theories, as long as we wholeheartedly appreciate and experience, aesthetics naturally reveals itself in our lives. Therefore, this study aims to explore how artists express and convey their emotions through their artworks, and through the transformation of these painting artworks into ceramic art, enrich people’s enjoyment of life. It also seeks to understand how people appreciate and interpret the transformed artworks and the kind of life experiences these artworks evoke. Furthermore, the study delves into the possibilities of applying the “transformation of painting into ceramic” in art creation to provide references for artists when applying transformative approaches. The conclusions drawn from this study are as follows:

The evaluation of the polarized adjective attributes listed in this study for the eight artworks generally allows participants to distinguish between painting artworks and ceramic art. This is naturally influenced by the attributes of these two art forms. However, there still exist significant cognitive differences among different audience perspectives, which will be explored in future research.

The two-stage attribute model proposed in this study is feasible for audiences to understand the transformation process of different art creations. Such an approach also helps artists consider the feasibility of different creative modes and identify elements that capture the audience’s interest.

Regarding the two main issues explored in this study, the transformation model adopted by the artist has certain reference value. It assists creators in breaking free from existing creative thinking patterns and unleashing the infinite possibilities of different media and modes of expression.

In summary, the transformation of artworks is not merely a change in form, but an embodiment of the artist’s creative concepts and vision. These transformations represent a dialogue between the artist and the materials they manipulate, reflecting a deeper understanding of the world and the artist’s place within it. When these transformations resonate with the public, they serve as a powerful affirmation of the artist’s work. Public reception thus becomes a critical feedback mechanism, encouraging the artist to continue exploring and refining their approach. It also provides them with references for future artistic endeavors, as they can build upon the responses and interpretations of their audience.

However, the relationship between the artist’s creative process and its reception is not linear. While artistic creation is inherently subjective and personal, the artist’s engagement with the broader cultural and social context cannot be ignored. As such, the focus of future research should shift towards identifying replicable experiences or patterns from the artist’s creative thinking process. By extracting these patterns, we can gain insights into how individual creativity can align with universal themes or trends in the broader art world. This approach would enable future generations of artists to refine their creative processes based on a more structured understanding of artistic innovation. The intersection of subjective vision and the shared cultural space in which artists work remains a fertile area for further academic exploration.

Art functions as more than just a vehicle for individual expression; it is an essential conduit for cultural transmission and the preservation of collective memory. Through their work, artists engage with the cultural content that has shaped their identity and the society they inhabit. As they navigate the creative process, their understanding of these cultural narratives deepens, often leading to new interpretations or reconnections with historical traditions. Artists not only seek inspiration across different mediums and forms but also bear the responsibility of cultural heritage—this dual role allows for the continuous evolution of cultural narratives through the arts. Their works, whether rooted in traditional techniques or innovative reinterpretations, provide a means for cultural continuity, bridging the gap between the past and present.

For audiences, a single artistic expression can become predictable or monotonous, limiting the potential for deeper engagement. It is through the diversity of art forms that an audience is truly invited to explore the richness of human experience, engaging with the layers of meaning embedded in each piece. The encounter with art becomes more than just a sensory experience; it is a catalyst for intellectual and emotional exploration, prompting reflection on cultural, historical, and personal contexts. Thus, the diversification of artistic expression serves to stimulate curiosity, leading viewers to uncover the multifaceted cultural meanings behind the artwork.

Although this study focuses on a selected range of works by a single artist, its implications extend beyond individual pieces. By drawing attention to innovative creative approaches, it encourages other artists to consider similar transformative techniques in their own practice. It highlights the potential for the cross-pollination of ideas and methods, fostering a broader understanding of how materials, techniques, and cultural narratives can be interwoven to create impactful works. In this context, cultural transmission and sustainability are not static or one-dimensional; they must be considered from a multiplicity of perspectives. The immediacy and accessibility of art to diverse audiences play a crucial role in ensuring that art remains a dynamic force for cultural exchange and continuity. As society continues to evolve, the role of art in fostering cultural sustainability and continuity becomes increasingly important, emphasizing the need for ongoing dialogue between artists, audiences, and cultural institutions.

In conclusion, the transformation of art is a dynamic process that extends beyond aesthetic change to touch upon broader themes of cultural exchange, continuity, and the evolution of creative expression. Future research should not only explore the technical and conceptual aspects of artistic transformation but also examine the deeper cultural implications of these transformations. By doing so, we can gain a more profound understanding of art’s role in shaping both individual and collective identity, as well as its potential to foster sustainable cultural practices in an increasingly globalized world.

Moreover, as this study marks the beginning of a series of investigations, it has certain limitations. For instance, the artworks analyzed come from a single artist, and future research could involve multiple artists to provide a broader perspective. Additionally, inviting more participants, especially those without an artistic background, would be beneficial in better understanding the general public’s perceptions of artworks created with different materials as media. This would also offer valuable insights into how the concept of material transformation enhances the appeal of artworks. Of course, we also consider that future studies could involve team members with backgrounds in material science, potentially enabling a deeper exploration of the properties of materials and the advantages and potential of various materials as artistic media.