Vision Measurement of Twisting a Double-Bimorph Piezoelectric Actuator

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

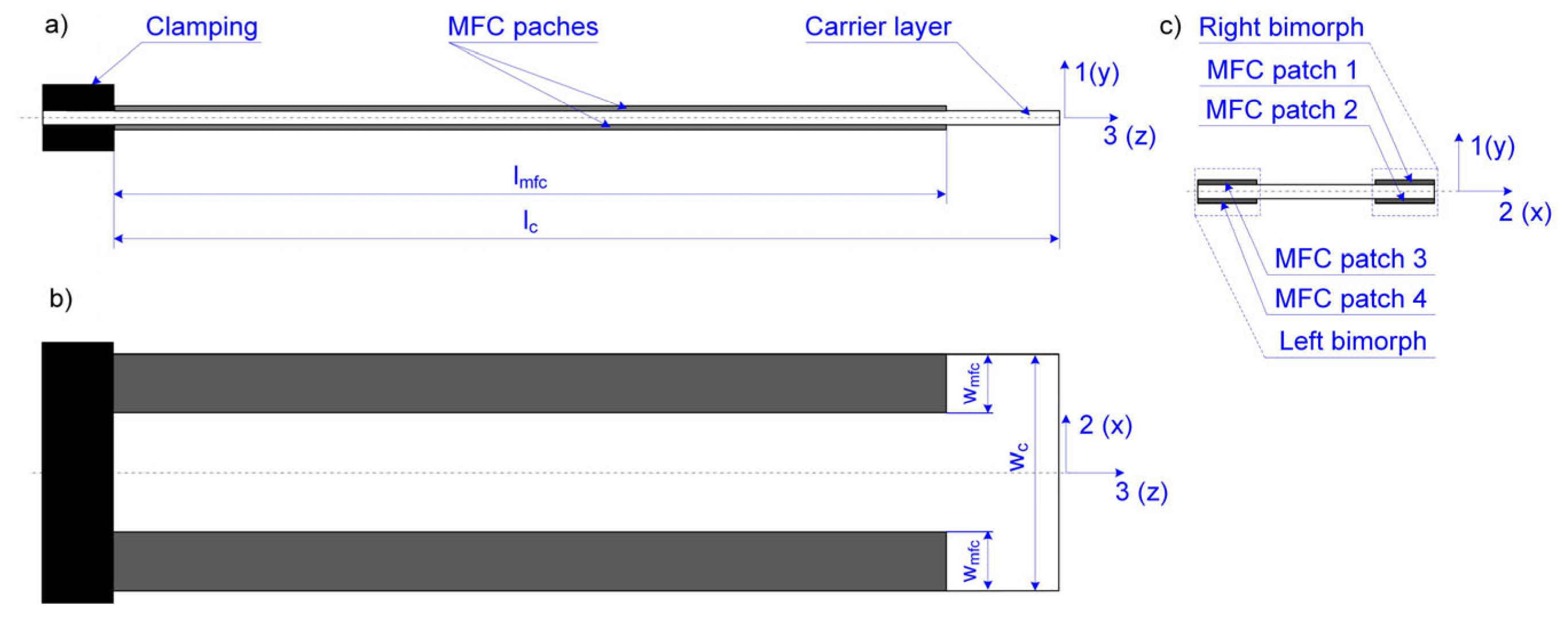

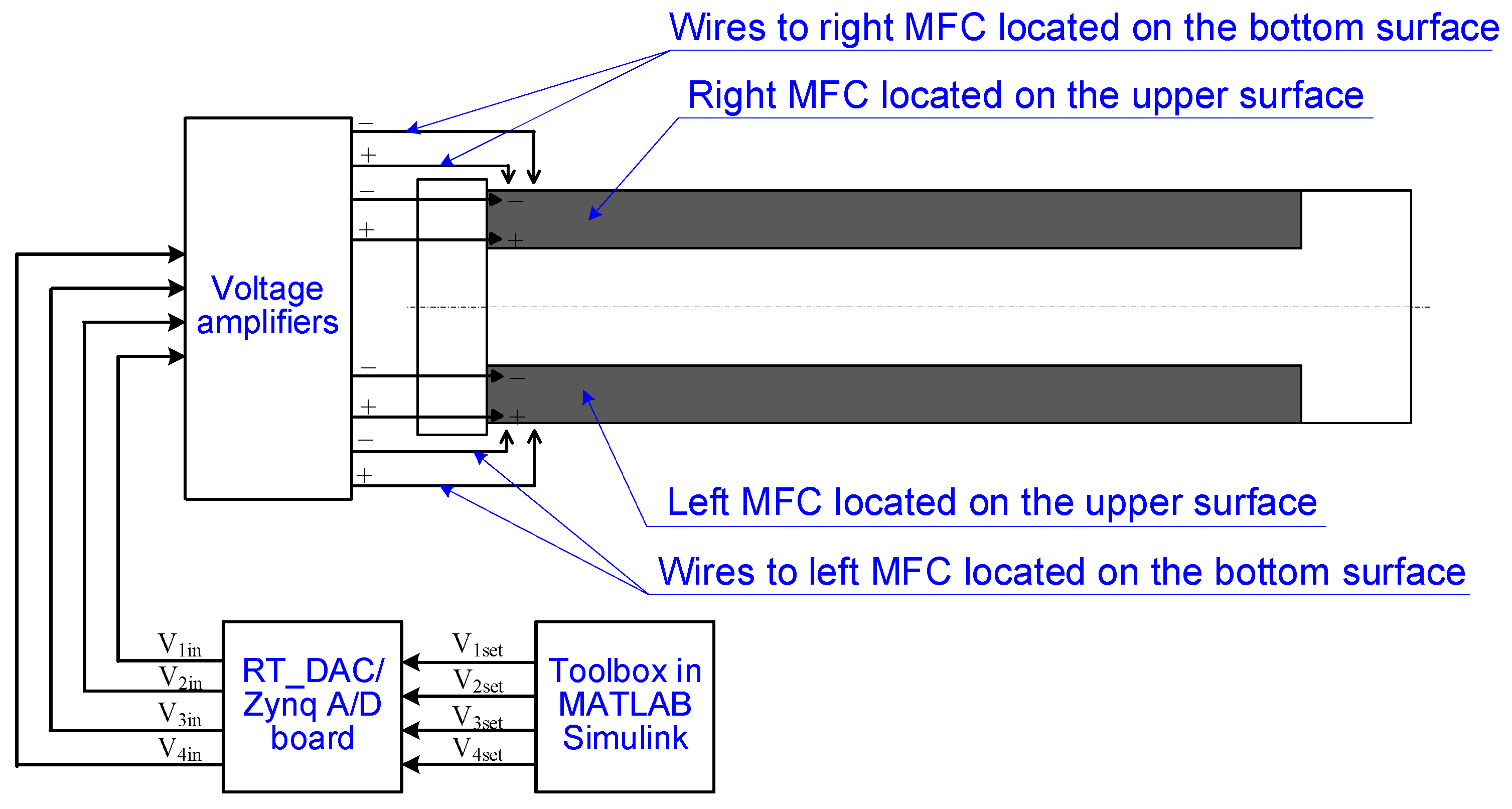

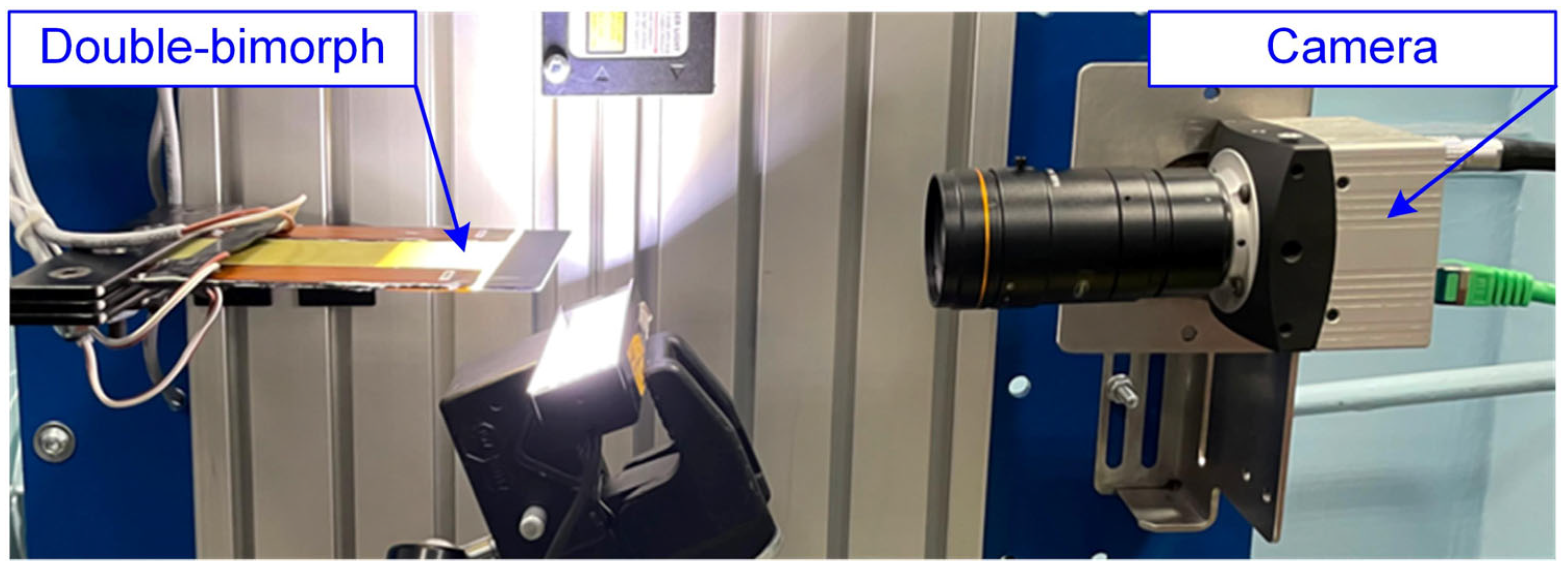

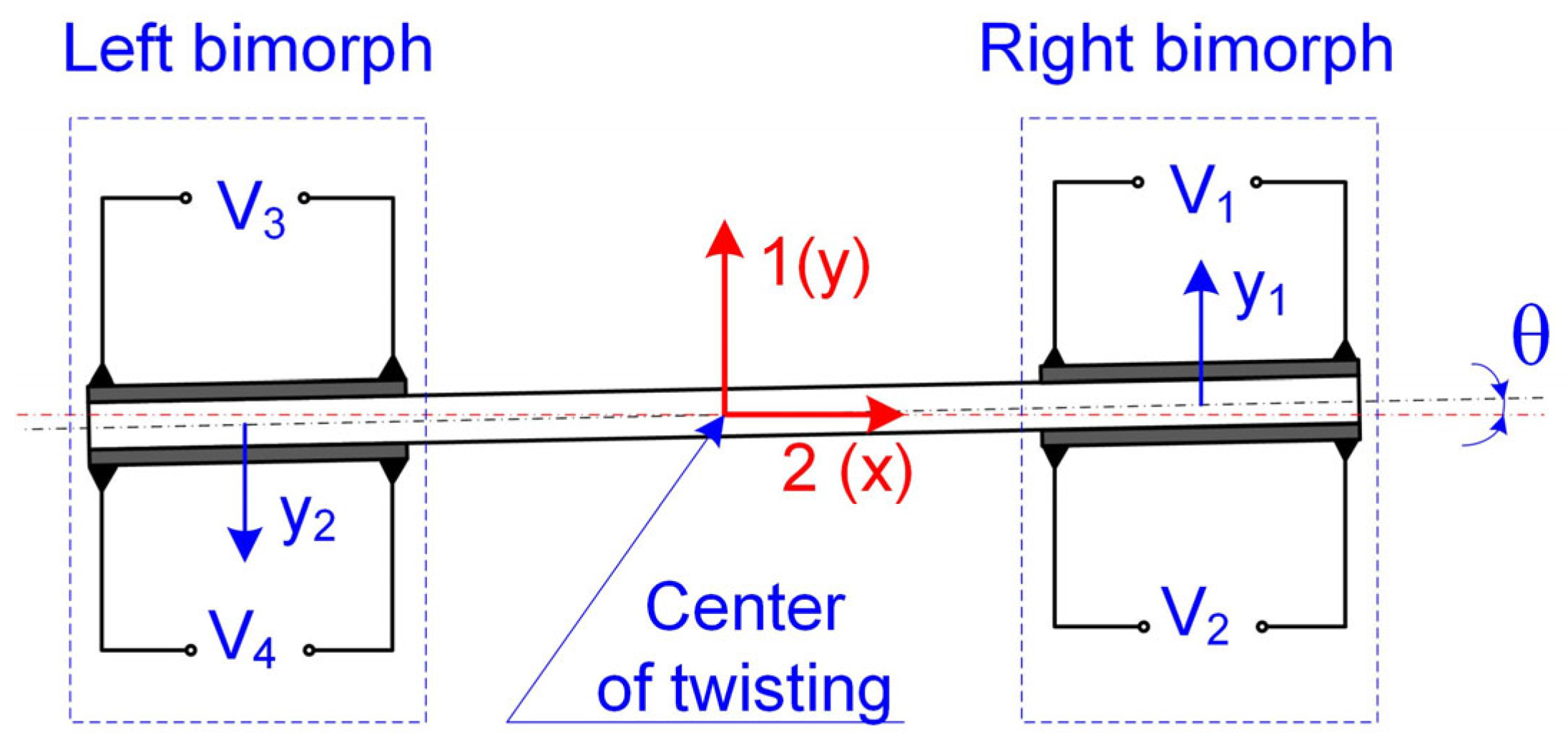

2. Materials and Methods

3. Mathematical Model of Double-Bimorph Actuator

4. Results

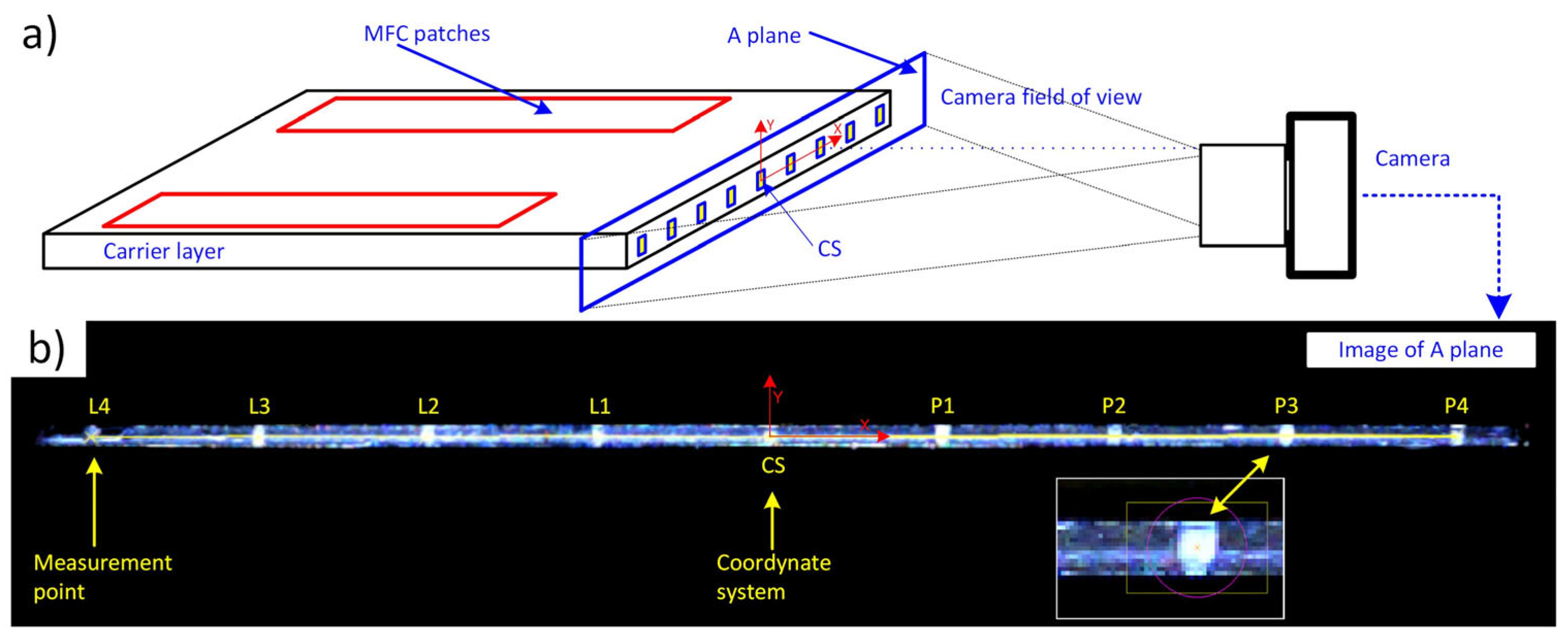

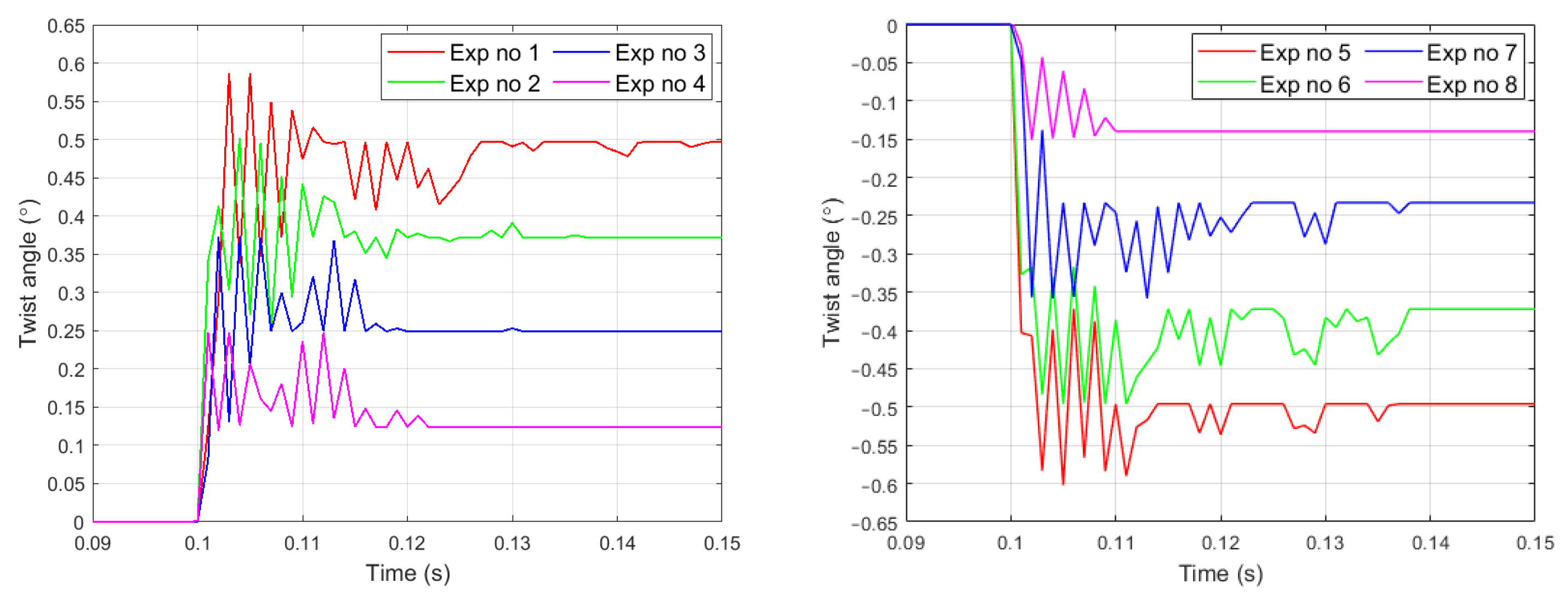

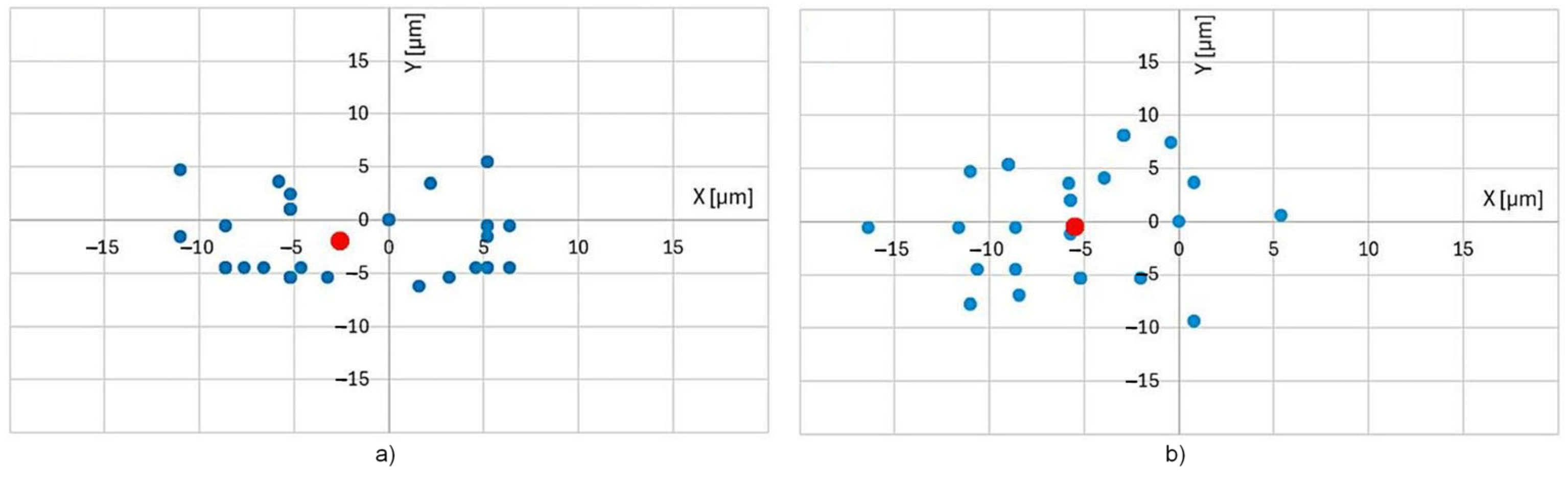

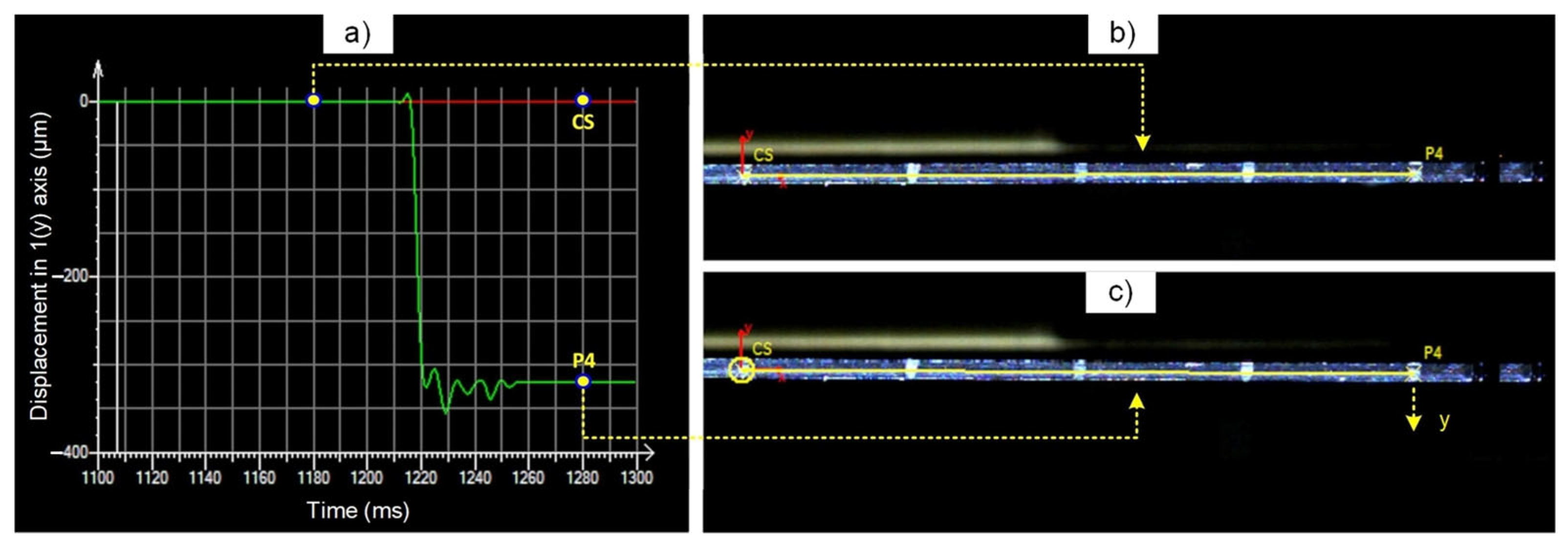

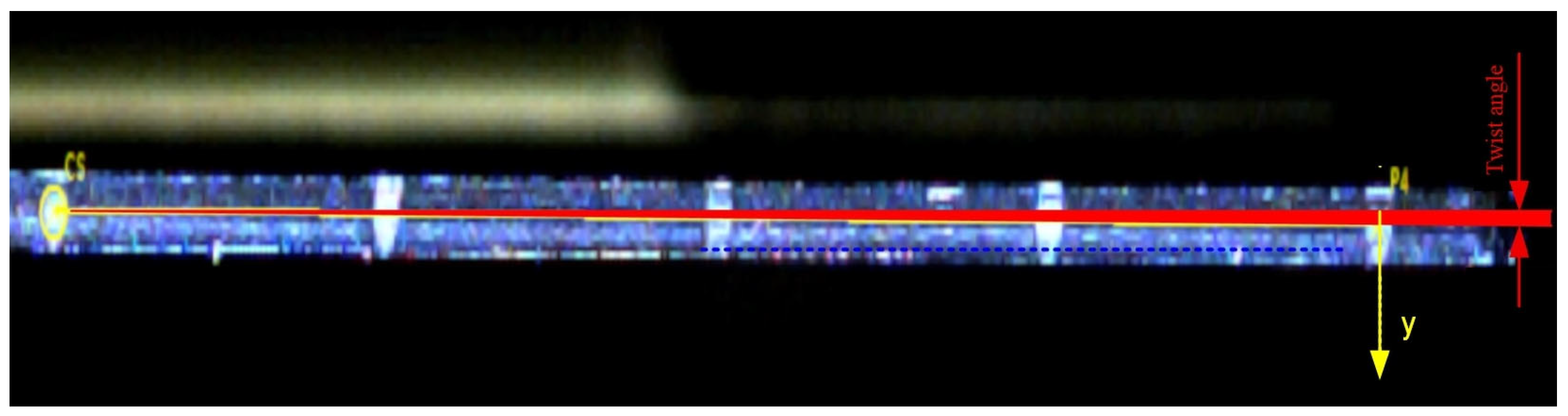

4.1. Measurement of a Twist Angle Using Vision Method

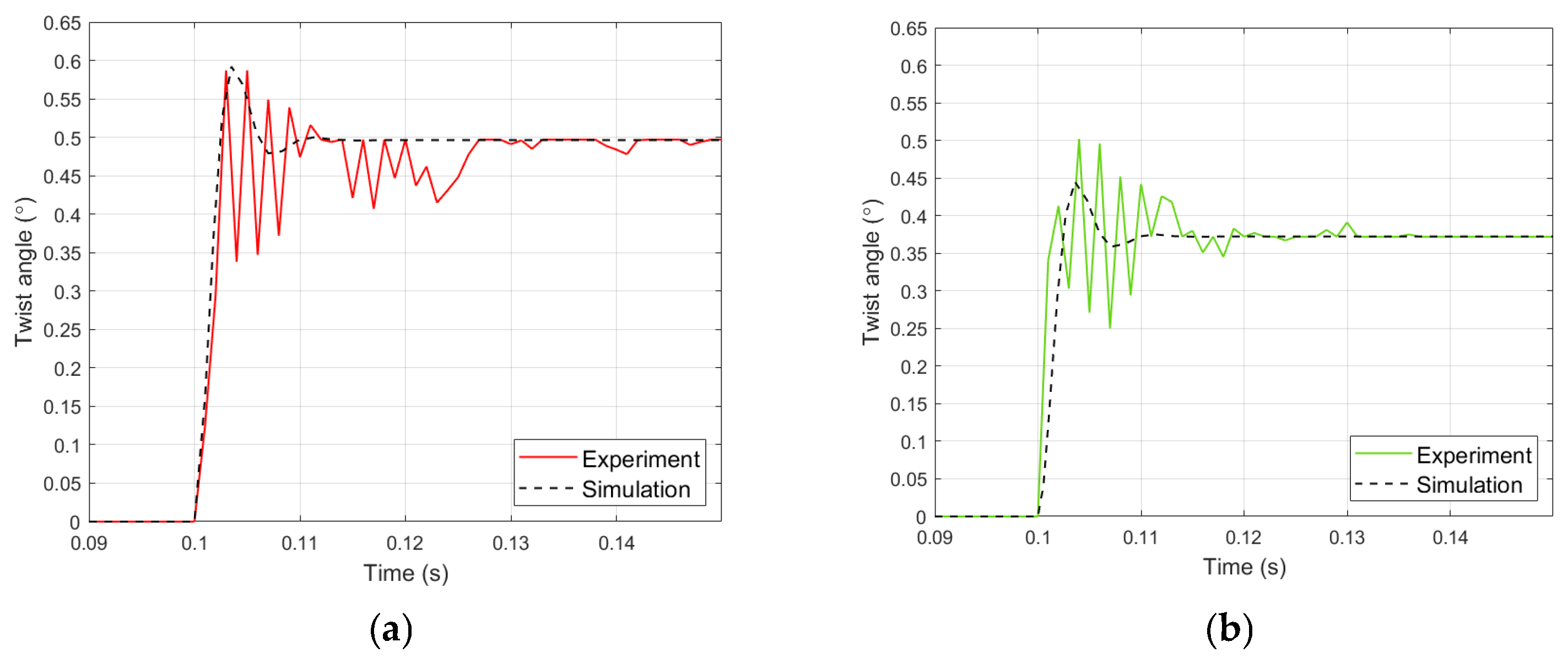

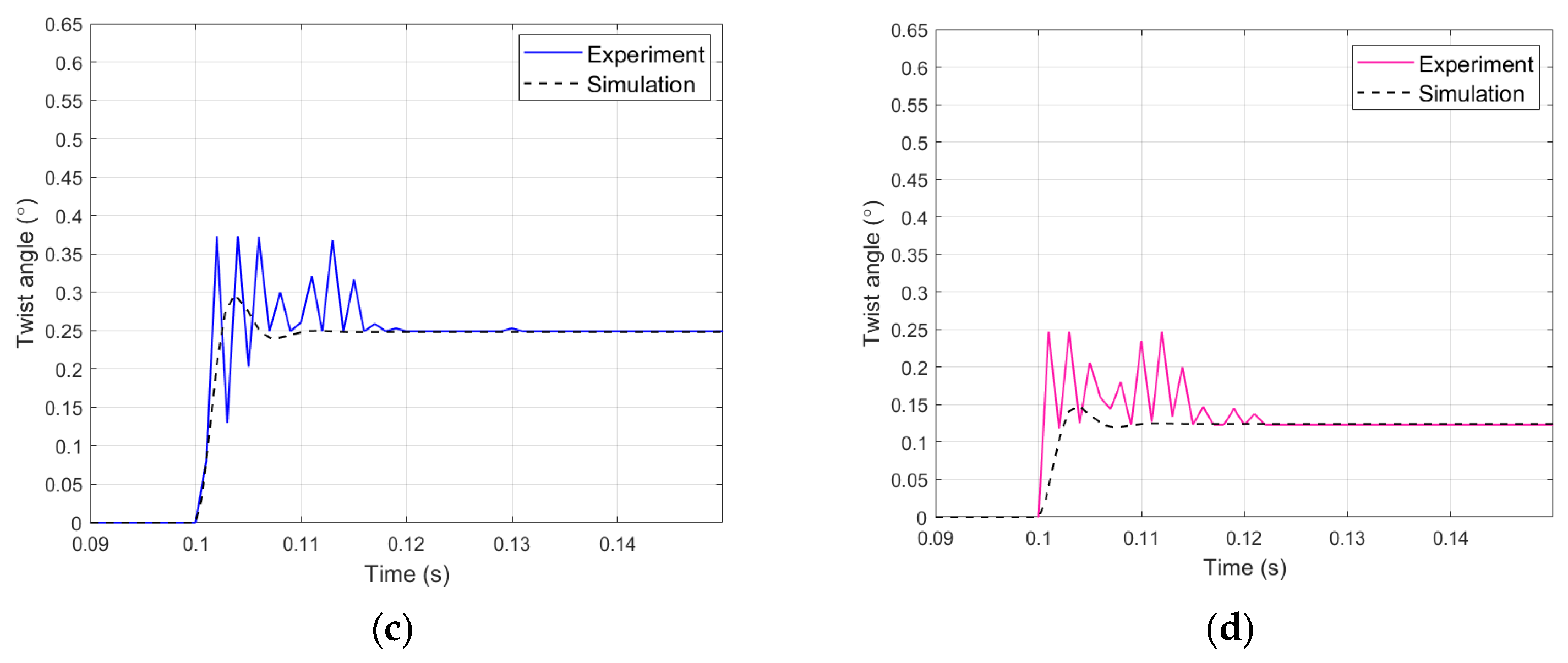

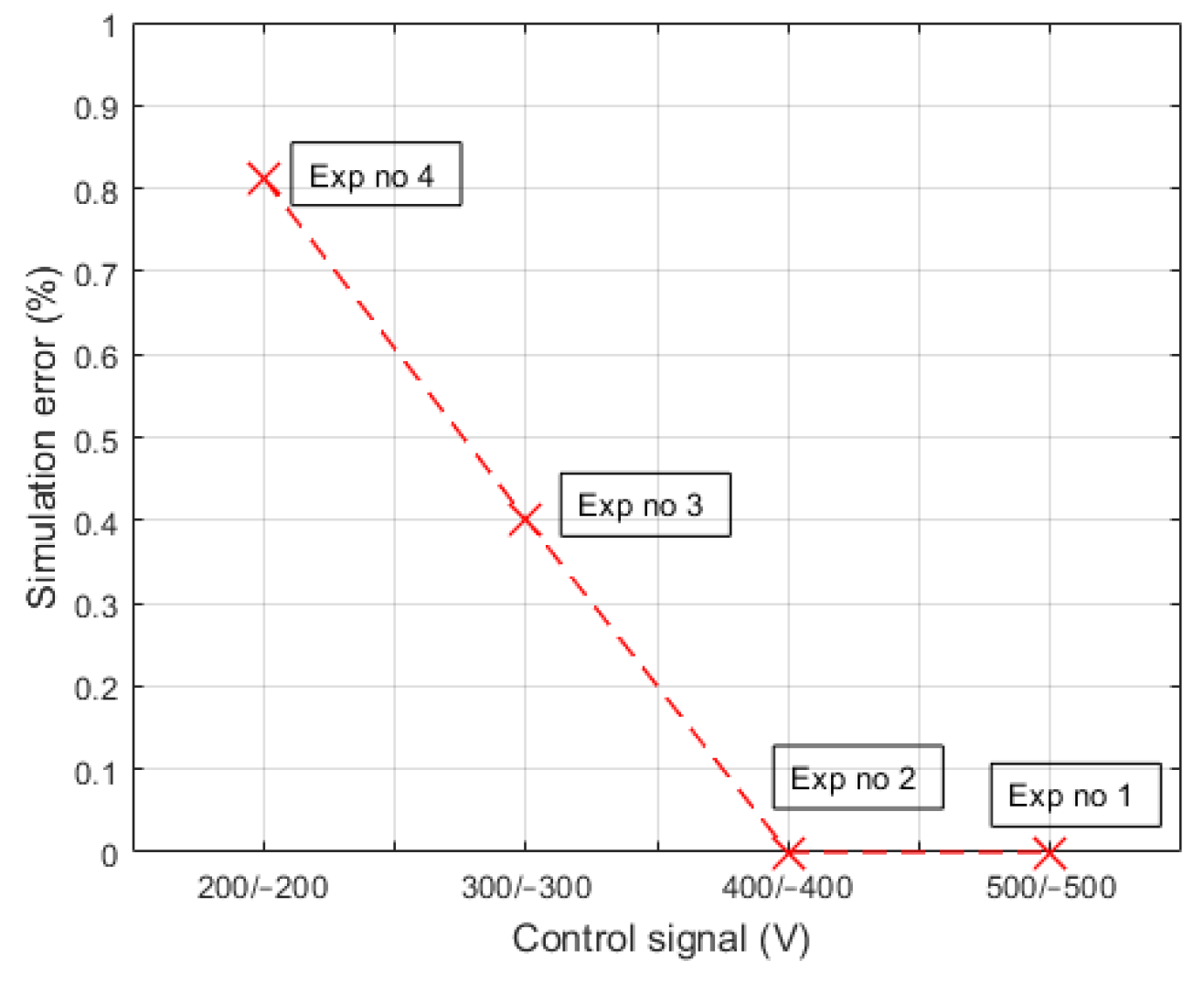

4.2. Simulation of a Twist Angle

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- Verification of the mathematical model, which is to be used in open-loop control of the twist angle of a double-bimorph actuator. In the measured actuator, it was found that the linear mathematical model correctly describes the conversion of electrical energy into the twist angle of this actuator because the effects of the creep phenomenon were not noticeable.

- Correction of the mathematical model of a double-bimorph actuator. In the measured actuator, it was found that the twist angle was smaller by a constant equal value regardless of the value of the applied symmetrical voltages, and such a correction was introduced into the linear mathematical model.

- Checking the correctness of the production of a double-bimorph actuator, e.g., gluing. In the measured actuator, a pure twisting was confirmed because the center of twisting was in the center of the actuator.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Mohith, S.; Upadhya, A.R.; Karanth, N.; Kulkarni, S.M.; Rao, M. Recent trends in piezoelectric actuators for precision motion and their applications: A review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 30, 013002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, A.M.; Ali, S.F.; Arockiarajan, A. Piezoelectric unimorph and bimorph cantilever configurations: Design guidelines and strain assessment. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramegowda, P.C.; Ishihara, D.; Takata, R.; Niho, T.; Horie, T. Finite element analysis of a thin piezoelectric bimorph with a metal shim using solid direct-piezoelectric and shell inverse-piezoelectric coupling with pseudo direct-piezoelectric evaluation. Compos. Struct. 2020, 245, 112284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Youcef-Toumi, K. Principle, implementation, and applications of charge control for piezo-actuated nanopositioners: A comprehensive review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 171, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Yavarow, P.; Erturk, A. Nonlinear elastodynamics of piezoelectric macro-fiber composites with interdigitated electrodes for resonant actuation. Compos. Struct. 2018, 187, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Hao, Z.W.; Yu, J.X.; Zhou, X.R.; Lee, P.S.; Sun, Y.; Mu, Z.C.; Zeng, F.L. A high-performance soft actuator based on a poly (vinylidene fluoride) piezoelectric bimorph. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 055011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.M.; Li, H.; Wen, L.H. Experimental study of axial-compressed macro-fiber composite bimorph with multi-layer parallel actuators for large deformation actuation. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2020, 31, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröck, J.; Meurer, T.; Kugi, A. Control of a flexible beam actuated by macro-fiber composite patches: II. Hysteresis and creep compensation, experimental results. Smart Mater. Struct. 2010, 20, 015016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Z.; Wu, W. Optimal unimorph and bimorph configurations of piezocomposite actuators for bending and twisting vibration control of plate structures. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2018, 29, 1685–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finio, B.M.; Wood, R.J. Optimal energy density piezoelectric twisting actuators. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 25–30 September 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 384–389. [Google Scholar]

- Gohari, S.; Sharifi, S.; Vrcelj, Z. A novel explicit solution for twisting control of smart laminated cantilever composite plates/beams using inclined piezoelectric actuators. Compos. Struct. 2017, 161, 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, I.H.; Maccabi, N.; Kassie, A.; Elata, D. A piezoelectric twisting beam actuator. J. Microelectromech. Syst. 2017, 26, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, W.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X. Integrated design of laminated composite structures with piezocomposite actuators for active shape control. Compos. Struct. 2019, 215, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zhang, Y.; Kraśny, M.J.; Rhead, A.; Bowen, C.; Arafa, M. Energy harvesting from coupled bending-twisting oscillations in carbon-fibre reinforced polymer laminates. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 107, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Dias, J.A.; de Sousa, V.C.; Erturk, A.; Junior, C.D.M. Nonlinear piezoelectric plate framework for aeroelastic energy harvesting and actuation applications. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Kohtanen, E.; Erturk, A. Characterization of a multifunctional bioinspired piezoelectric swimmer and energy harvester. In Proceedings of the ASME 2020 Conference on Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems, Virtual, 14–16 September 2020; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rakotondrabe, M.; Clévy, C.; Lutz, P. Complete open loop control of hysteretic, creeped, and oscillating piezoelectric cantilevers. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2009, 7, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Gravish, N. Piezoelectric actuators with on-board sensing for micro-robotic applications. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 115036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybek, D. Control System for Multi-Input and Simple-Output Piezoelectric Beam Actuator Based on Macro Fiber Composite. Energies 2022, 15, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deraemaeker, A.; Nasser, H.; Benjeddou, A.; Preumont, A. Mixing rules for the piezoelectric properties of macro fiber composites. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2009, 20, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, J.; Wu, Z. Theoretical and experimental investigations on modified LQ terminal control scheme of piezo-actuated compliant structures in finite time. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 491, 115762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macro Fiber Composite (MFC) Data Sheet. Available online: https://smart-material.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/MFC_V2.4-datasheet-web.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Azam, S.A.; Fragoso, A. Experimental and Numerical Simulation Study of the Vibration Properties of Thin Copper Films Bonded to FR4 Composite. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Arockiarajan, A. Actuation performance of macro-fiber composite (MFC): Modeling and experimental studies. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2016, 248, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuno, H.; Saigusa, S.; Aoshima, N. Stabilization of the parametric resonance of a cantilever beam by bifurcation control with a piezoelectric actuator. Nonlinear Dyn. 2001, 26, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayanthatta, N.; Clementi, G.; Ouhabaz, M.; Margueron, S.; Bartasyte, A.; Lallart, M.; Basrour, S.; La Rosa, R.; Bano, E.; Montes, L. Electro-Mechanical Characterization and Modeling of a Broadband Piezoelectric Microgenerator Based on Lithium Niobate. Sensors 2024, 24, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, B.; Zhu, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, M. A hybrid piezoelectric and electromagnetic broadband harvester with double cantilever beams. Micromachines 2023, 14, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, W.; Luo, H.; Zhang, R. Modeling and active control of geometrically nonlinear vibration of composite laminates with macro fiber composite. Compos. Struct. 2023, 321, 117292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarianand, D.V.; Karthikeyan, P.; Muthuramalingam, T. A review on control strategies for compensation of hysteresis and creep on piezoelectric actuators based micro systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 140, 106634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devies, E.R. Computer and Machine Vision: Theory, Algorithms, Practicalities; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dadhich, A. Practical Computer Vision: Extract Insightful Information from Images Using TensorFlow, Keras, and OpenCV; Packt Publishing: Birmingham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sioma, A. Vision system in product quality control systems. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioma, A.; Lenty, B. Focus estimation methods for use in industrial SFF imaging systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Shen, G.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J. Transverse Vibration Measurement of Beam Structure Using Based on Subpixel-Based Edge Detection and Point Tracking. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 2671–26811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, E.S. The cantilevered beam: An analytical solution for general deflections of linear-elastic materials. Eur. J. Phys. 2006, 27, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.M.; Cross, L.E. Determination of Young’s modulus of the reduced layer of a piezoelectric RAINBOW actuator. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 83, 5358–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, S.; Wright, P.K.; Rabaey, J.M. Energy Scavenging for Wireless Sensor Networks; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Su, C. Computation of Rayleigh damping coefficients for the seismic analysis of a hydro-powerhouse. Shock. Vib. 2017, 1, 2046345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirovitch, L. Fundamentals of Vibrations; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Zheng, C.; Ruan, X.; Zeng, J.; Zheng, L.; Chen, W.; Li, G. Elastic and electric damping effects on piezoelectric cantilever energy harvesting. Ferroelectrics 2014, 459, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Symbol | Value | Dimension | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall length of MFC patch | lmfc | 101 | Distance between centers of bimorphs | wd | 70 |

| Overall width of MFC patch | wmfc | 20 | Length of an active part in MFC patch | lmfca | 85 |

| Overall thickness of MFC patch | tmfc | 0.3 | Length of a passive part in MFC patch | lmfcp | 7.5 |

| Length of carrier layer | lc | 120 | Width of an active area in MFC patch | wmfca | 14 |

| Width of carrier layer | wc | 80 | Thickness of an active area in MFC patch | tmfca | 0.18 |

| Thickness of carrier layer | tc | 1 | Distance among electrodes in MFC patch | tmfce | 0.5 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compliance constant under constant electric field | 23.708 × 10−12 | m2/N | |

| Piezoelectric constant of fibers in MFC patch | d33 | 436 × 10−12 | C/N |

| Density of MFC patch | ρmfc | 5400 | kg/m3 |

| Young’s modulus of an MFC patch | Ymfc | 30.33 × 109 | N/m2 |

| Density of a carrier layer | ρc | 1850 | kg/m3 |

| Young’s modulus of a carrier layer | Yc | 18.6 × 109 | N/m2 |

| Exp 1 | Exp 2 | Exp 3 | Exp 4 | Exp 5 | Exp 6 | Exp 7 | Exp 8 | Exp 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 (V) | −500 | −400 | −300 | −200 | +500 | +400 | +300 | +200 | −500 |

| V2 (V) | +500 | +400 | +300 | +200 | −500 | −400 | −300 | −200 | +500 |

| V3 (V) | +500 | +400 | +300 | +200 | −500 | −400 | −300 | −200 | +500 |

| V4 (V) | −500 | −400 | −300 | −200 | +500 | +400 | +300 | +200 | −500 |

| Duration (s) | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 40 |

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stiffness coefficient | k11 | 573 | N/m |

| Stiffness coefficient | k22 | 573 | N/m |

| Stiffness coefficient | k12 | 800 | N/m |

| Stiffness coefficient | k21 | 718 | N/m |

| Rayleigh damping coefficient | α | 127.74 | - |

| Rayleigh damping coefficient | β | 4.25 × 10−5 | - |

| Actuator mass | ma | 0.0092 | kg |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grzybek, D.; Sioma, A. Vision Measurement of Twisting a Double-Bimorph Piezoelectric Actuator. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13109. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413109

Grzybek D, Sioma A. Vision Measurement of Twisting a Double-Bimorph Piezoelectric Actuator. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13109. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413109

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrzybek, Dariusz, and Andrzej Sioma. 2025. "Vision Measurement of Twisting a Double-Bimorph Piezoelectric Actuator" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13109. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413109

APA StyleGrzybek, D., & Sioma, A. (2025). Vision Measurement of Twisting a Double-Bimorph Piezoelectric Actuator. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13109. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413109