Finite-Element Simulations of the Static Behavior and Explosive-Rupture Dynamics of 500 kV SF6 Porcelain Hollow Bushings

Abstract

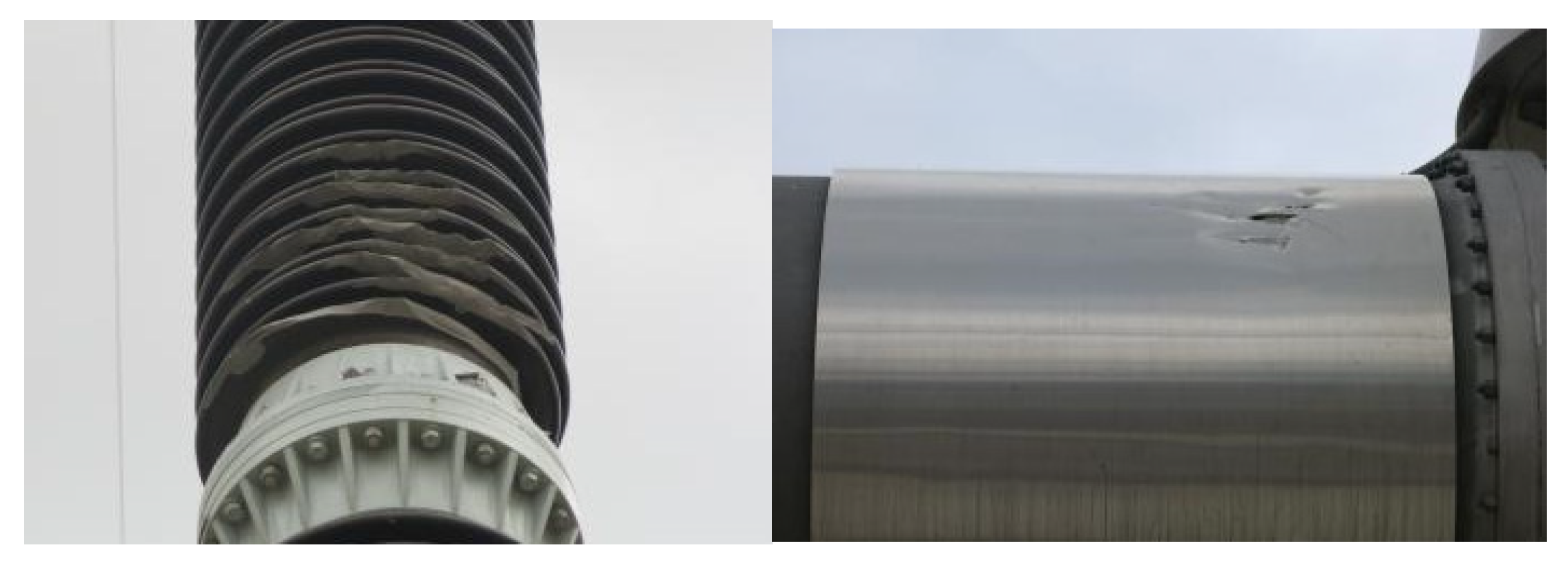

1. Introduction

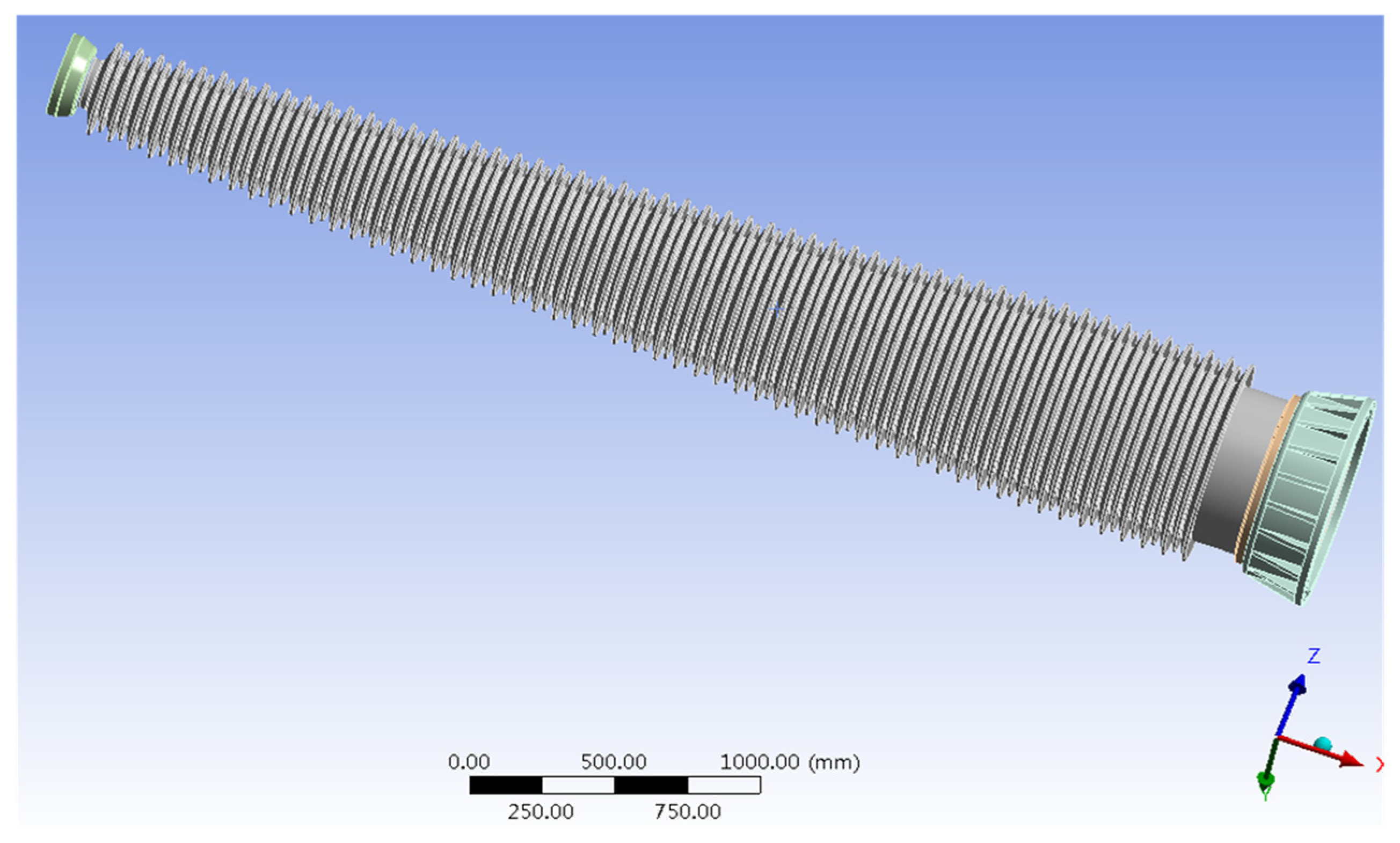

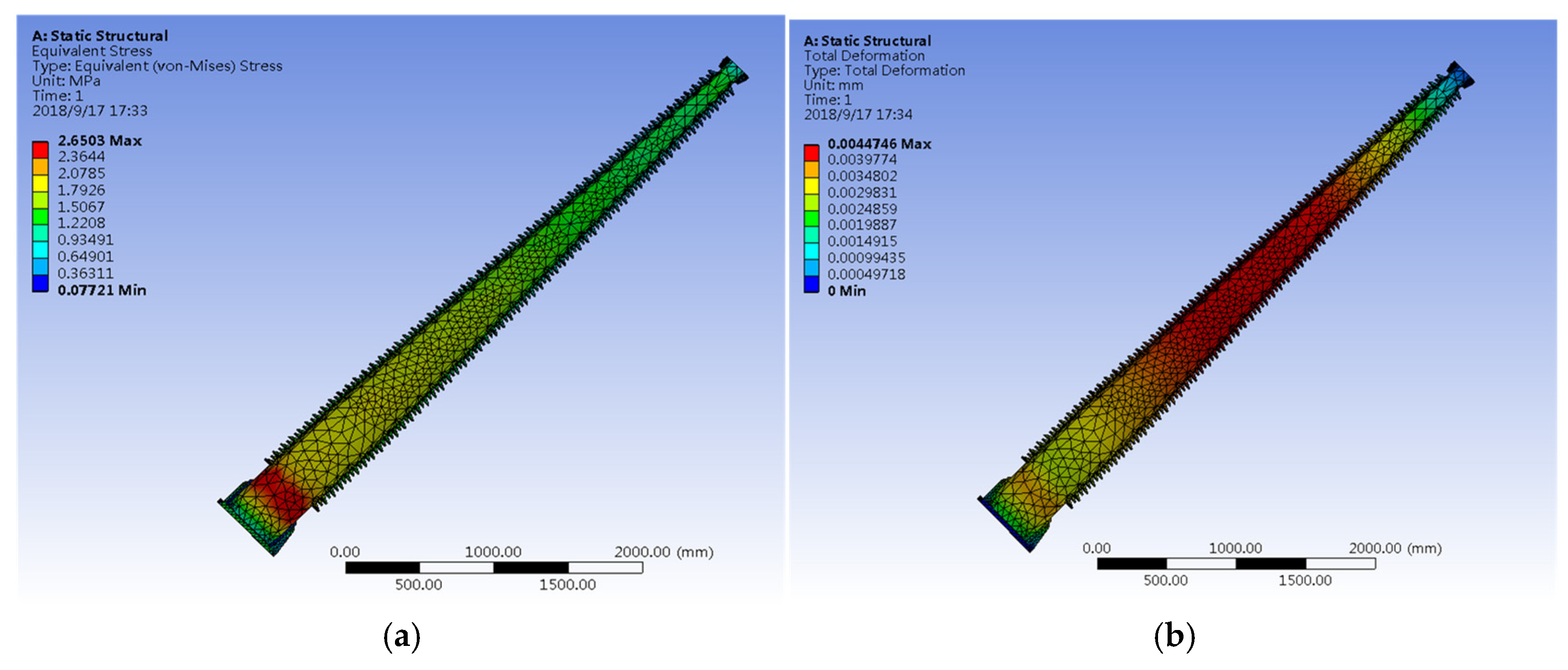

2. Stress Analysis of the Bushing

3. Dynamic Simulation of the Bushing Rupture Process

3.1. Mechanism of Bushing Rupture

3.1.1. Energy of Rupture Due to Crack Growth and Gas Expansion

3.1.2. Energy Associated with Internal Discharge

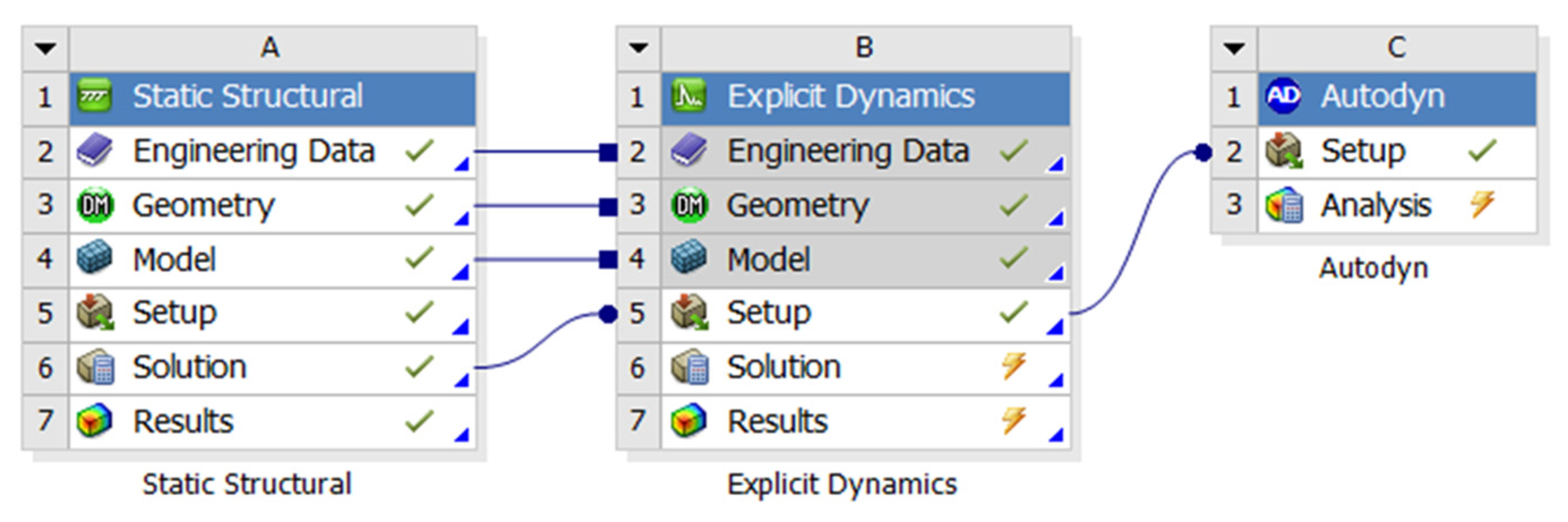

3.2. Principle of Dynamic Simulation for the Bushing Rupture Process

3.3. Dynamic Simulation of the Rupture Process

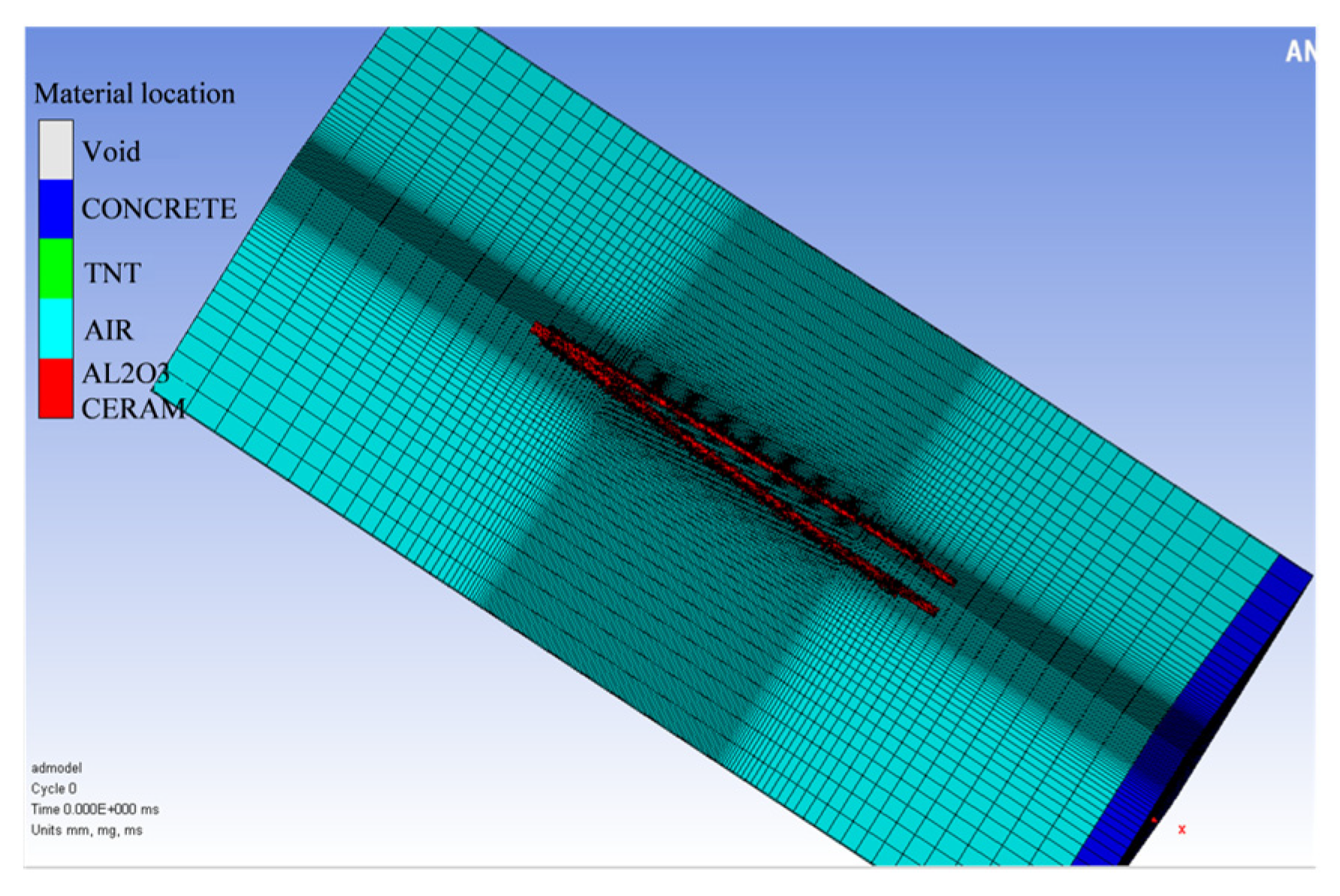

3.3.1. Construction of the Simulation Model

3.3.2. AUTODYN Parameter Settings

3.3.3. Executing the AUTODYN Solution

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Static finite-element analysis indicates that the porcelain–flange transition experiences the maximum equivalent (von Mises) stress. When the potting length at the flange is insufficient or assembly interference is present, the local strength margin diminishes and cracking/rupture is more likely. Waterproofing of the potted region is required to suppress moisture uptake and freeze–thaw-induced constraint and degradation.

- (2)

- Under internal SF6 pressure, strain concentrates near the mid-span of the bushing. For multi-section (segmented) designs, the material quality and process consistency of the adhesive joint directly govern resistance to debonding. Improving adhesive formulation and bonding procedures is therefore critical to preventing joint separation and subsequent burst of segmented bushings.

- (3)

- Using azimuth–distance–mass data from 14 field fragments and the Gurney formula for hollow-cylindrical charges, the back-estimated equivalent TNT is 55–75 g (≈250.8–342 kJ), while the SF6 gas burst energy computed via an adiabatic-expansion approximation is 292.833 kJ. The comparable magnitudes and overlapping ranges support the consistency of the energy setting and mechanism assessment, and indirectly suggest the plausibility of a failure sequence in which gas-driven rupture precedes secondary discharge.

- (4)

- After explicitly seeding multiple microcracks in the model, the simulated fragment mass spectrum and spatial dispersion agree with field observations, indicating that pores and microcracks exert a decisive influence on fracture strength and fragmentation mode. Brittle failure driven by internal crack extension is likely one of the principal causes of explosive-rupture. Process improvements—raw-material control and optimization of firing temperature/soak—can reduce internal defects and enhance in-service reliability.

- (5)

- The results provide quantitative guidance for manufacturing and O&M, helping to reduce explosive-rupture incidents and safeguard power-transmission safety. Future work should refine long-term reliability assessment under coupled environmental loads, develop higher-sensitivity methods for detecting and quantitatively inferring internal microcracks, and explore materials and process routes that improve anti-burst capability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arias Velásquez, R.M.; Mejía Lara, J.V. Bushing failure in power transformers and the influence of moisture with the spectroscopy test. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2018, 94, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, L.; Wang, W.; Han, Y.; Pu, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, H. Intelligent monitoring of EHV transformer bushing based on multi-parameter composite sensing technology. IET Sci. Meas. Technol. 2023, 17, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knock, C.; Horsfall, I.; Champion, S.M. Development of a computer model to predict risks from an electrical bushing failure. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2013, 103, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knock, C.; Horsfall, I.; Champion, S.M. Effect of core size and ground surface on debris fields of failed electric bushings. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2013, 104, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluss, J.; Chalaki, M.R.; Whittington, W.; Rhee, H.; Whittington, S.; Yadollahi, A. Porcelain insulation—defining the underlying mechanism of failure. High Volt. 2019, 4, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wu, M.e.; Xie, Q. Comparison of engineering failures and seismic responses of 500 kV transformer-bushing systems in the 2022 Luding earthquake. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Vib. 2024, 23, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Du, J.; Lei, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, W.; Yi, X.; Yin, J.; Yu, P. Effect of pores on dielectric breakdown strength of alumina ceramics via surface and volume effects. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 3019–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, B.; Tiwari, D.; Kundu, D.; Prasad, R. Is Weibull distribution the most appropriate statistical strength distribution for brittle materials? Ceram. Int. 2009, 35, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.B.; Quinn, G.D. A practical and systematic review of Weibull statistics for reporting strengths of dental materials. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damião, L.; Guimarães, J.; Ferraz, G.; Bortoni, E.; Rossi, R.; Capelini, R.; Salustiano, R.; Tavares, E. Online Monitoring of Partial Discharges in Power Transformers Using Capacitive Coupling in the Tap of Condenser Bushings. Energies 2020, 13, 4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.; Kim, T.; Yi, J.; Koo, J.-B.; Son, J.-A.; Choi, I.-H. Failure Trends of High-Voltage Porcelain Insulators Depending on the Constituents of the Porcelain. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Accio, F.; Di Tommaso, F.; Guessab, A.; Nudo, F. A General Class of Enriched Methods for the Simplicial Linear Finite Elements. Appl. Math. Comput. 2023, 456, 128149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tobias Gudmestad, O.; Igland, R. Numerical Simulation of a Subsea Pipeline Subjected to Underwater Explosion Loads With the Coupled Eulerian–Lagrangian Method. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 2022, 144, 061901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, Z.; Cao, P.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Jiang, X.; Tian, L.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, H. Study on the Ultimate Load Failure Mechanism and Structural Optimization Design of Insulators. Materials 2024, 17, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortigón, B.; Rodríguez-Mayorga, E.; Santiago-Espinal, J.A.; Ancio, F.; Gallardo, J.M. Influence of Materials of Moulds and Geometry of Specimens on Mechanical Properties of Grouts Based on Ultrafine Hydraulic Binder. Materials 2024, 17, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, D.; Wahlbom, D.; Malm, R.; Fridh, K. Hygro-thermo-mechanical modeling of partially saturated air-entrained concrete containing dissolved salt and exposed to freeze-thaw cycles. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 141, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Liu, H.; He, F.; Wang, W.; Miao, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, J.; Shi, C. Freeze–Thaw Damage Characteristics of Concrete Based on Compressive Mechanical Properties and Acoustic Parameters. Materials 2024, 17, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Z. Study on the Bending Stiffness of Joints Connecting Porcelain Bushings and Flanges in Ultra-High Voltage Electrical Equipment. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, M.; Iqbal, T.; Hussain, M.A.; Tabish, A.N.; Haq, E.U.; Siddiqi, M.H.; Yasin, S.; Mahmood, H. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of high strength porcelain insulators for power transmission and distribution applications. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 1603–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, K.; He, R.; Qu, Z. A review of thermal shock behavior of ceramics: Fundamental theory, experimental methods, and outlooks. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2024, 21, 3789–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradkhani, A.; Panahizadeh, V.; Hoseinpour, M. Indentation fracture resistance of brittle materials using irregular cracks: A review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, C.; Hu, K.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, P.; Lu, Z. Effect of sintering aids on mechanical properties and microstructure of alumina ceramic via stereolithography. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 17506–17523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.-S.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Qian, G. Standardized Weibull statistics of ceramic strength. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 4972–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuchukwu, O.A.; Salihi, A.; Ibrahim, A.; Audu, A.A.; Makoyo, M.; Mohammed, S.A.; Lawal, M.Y.; Etinosa, P.O.; Isaac, I.O.; Oni, P.G.; et al. Weibull analysis of ceramics and related materials: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, M.Y.; Alharthi, H.; Alfattani, R.; Suker, D.K.; Abu El-Ainin, H.M.; Mohamed, A.F.; Hassan, M.K.; Backar, A.H. Mechanical Properties and Fracture Toughness Prediction of Ductile Cast Iron under Thermomechanical Treatment. Metals 2024, 14, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, J. Study on the Partial Surface Discharge Process of Oil-Paper Insulated Transformer Bushing with Defective Condenser Layer. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, C.; Suo, T.; Wen, Y. Maximum fragment velocity of hollow charges with different aspect ratios. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 178, 104622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Feng, S.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Q. Fragment characteristics of cylinder with discontinuous charge. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2023, 173, 104479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitpas, G.; Aceves, S.M. The isentropic expansion energy of compressed and cryogenic hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 20319–20323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wu, C.; An, F.; Liao, S.; Yuan, X.; Xue, D.; Liu, J. Acceleration Characteristics of Discrete Fragments Generated from Explosively-Driven Cylindrical Metal Shells. Materials 2020, 13, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koli, S.; Chellapandi, P.; Bhaskara Rao, L.; Sawant, A. Study on JWL equation of state for the numerical simulation of near-field and far-field effects in underwater explosion scenario. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2020, 23, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Børvik, T.; Hanssen, A.G.; Langseth, M.; Olovsson, L. Response of structures to planar blast loads—A finite element engineering approach. Comput. Struct. 2009, 87, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganić, H.; Varevac, D. Analysis of Blast Wave Parameters Depending on Air Mesh Size. Shock Vib. 2018, 2018, 3157457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, E.C.; Weerheijm, J.; Toussaint, G.; Sluys, L.J. An experimental and numerical investigation of sphere impact on alumina ceramic. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2020, 145, 103670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candaş, A.; Oterkus, E.; İmrak, C.E. Dynamic Crack Propagation and Its Interaction With Micro-Cracks in an Impact Problem. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 2020, 143, 011003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Lin, C.K.; Bian, Y.L.; Xie, H.L.; Chai, H.W.; Ding, Y.Y.; Luo, S.N. Strain rate effects on fragment morphology of ceramic alumina: A synchrotron-based study. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 280, 109506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, N.F. Fragmentation of shell cases. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1997, 189, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Liu, Z. Study on the mesh size determination method of blast wave numerical simulation with strong applicability. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Guo, C.; Deng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Nie, X. Numerical Simulation Study of Expanding Fracture of 45 Steel Cylinders under Explosive Load. Materials 2022, 15, 3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Elastic Modulus, E (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio, ν | Density, ρ (kg·m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Porcelain | 110 | 0.35 | 2800 |

| Cement (grout) | 35 | 0.33 | 2600 |

| Cast iron | 200 | 0.30 | 7800 |

| Fragment ID | Azimuth (°) | Distance (m) | Mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 | 18.0 | 8.0 |

| 2 | 20 | 17.8 | 27.0 |

| 3 | 45 | 18.0 | 5.5 |

| 4 | 60 | 17.9 | 1.0 |

| 5 | 90 | 28.2 | 48.9 |

| 6 | 140 | 29.4 | 8.5 |

| 7 | 170 | 57.9 | 3.3 |

| 8 | 195 | 35.7 | 7.5 |

| 9 | 200 | 32.7 | 3.0 |

| 10 | 225 | 42.0 | 6.0 |

| 11 | 250 | 19.5 | 9.8 |

| 12 | 270 | 28.2 | 23.6 |

| 13 | 300 | 21.3 | 16.0 |

| 14 | 315 | 18.5 | 35.3 |

| Quantity | Field Data (14 Major Fragments, Table 2) | Numerical Simulation (10 Main Fragments, Figure 10b) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of fragments considered, N | 14 | 10 |

| Minimum fragment mass/kg | 1.0 | 5.4 |

| Maximum fragment mass/kg | 48.9 | 77.6 |

| Mean fragment mass/kg | 14.5 | 18.6 |

| Standard deviation of mass/kg | 14.1 | 22.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yue, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, L.; Lu, Z. Finite-Element Simulations of the Static Behavior and Explosive-Rupture Dynamics of 500 kV SF6 Porcelain Hollow Bushings. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12896. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412896

Yue Y, Zhao J, Yang L, Lu Z. Finite-Element Simulations of the Static Behavior and Explosive-Rupture Dynamics of 500 kV SF6 Porcelain Hollow Bushings. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12896. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412896

Chicago/Turabian StyleYue, Yonggang, Jianli Zhao, Lanjun Yang, and Zhijian Lu. 2025. "Finite-Element Simulations of the Static Behavior and Explosive-Rupture Dynamics of 500 kV SF6 Porcelain Hollow Bushings" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12896. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412896

APA StyleYue, Y., Zhao, J., Yang, L., & Lu, Z. (2025). Finite-Element Simulations of the Static Behavior and Explosive-Rupture Dynamics of 500 kV SF6 Porcelain Hollow Bushings. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12896. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412896