GNSS Vector Networks in a Local Conventional Reference Frame

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Traditional Procedure for GNSS Vector Conversion into Local Reference Frames

- Adjust GNSS vectors in the geocentric reference frame based on the WGS84 ellipsoid

- 2.

- Calculate adjusted Cartesian coordinates XYZ

- 3.

- Project the points onto the surface of the WGS84 reference ellipsoid (convert Cartesian coordinates XYZ to ellipsoidal coordinates BLh)

- 4.

- Project the BL ellipsoidal coordinates onto the plane of a local reference frame (such as xy2000)

- (4.1). Transform the ellipsoid into a sphere (Lagrange projection):

- (4.2). Apply transverse cylindrical Mercator projection:

- (4.3). Project the Mercator plane onto the Gauss-Krüger (G-K) plane:

- (4.4). Convert G-K coordinates into a local projection system (such as PL-2000):

- 5.

- Create a set of 2D vectors (for each vector ij)

- 6.

- Convert ellipsoidal heights (h) (7) into orthometric heights (Hn)

- 7.

- Create differences (increments) in normal heights (for each vector ij)

2.2. Procedure for Transforming GNSS Vectors into a Local Conventional Reference Frame

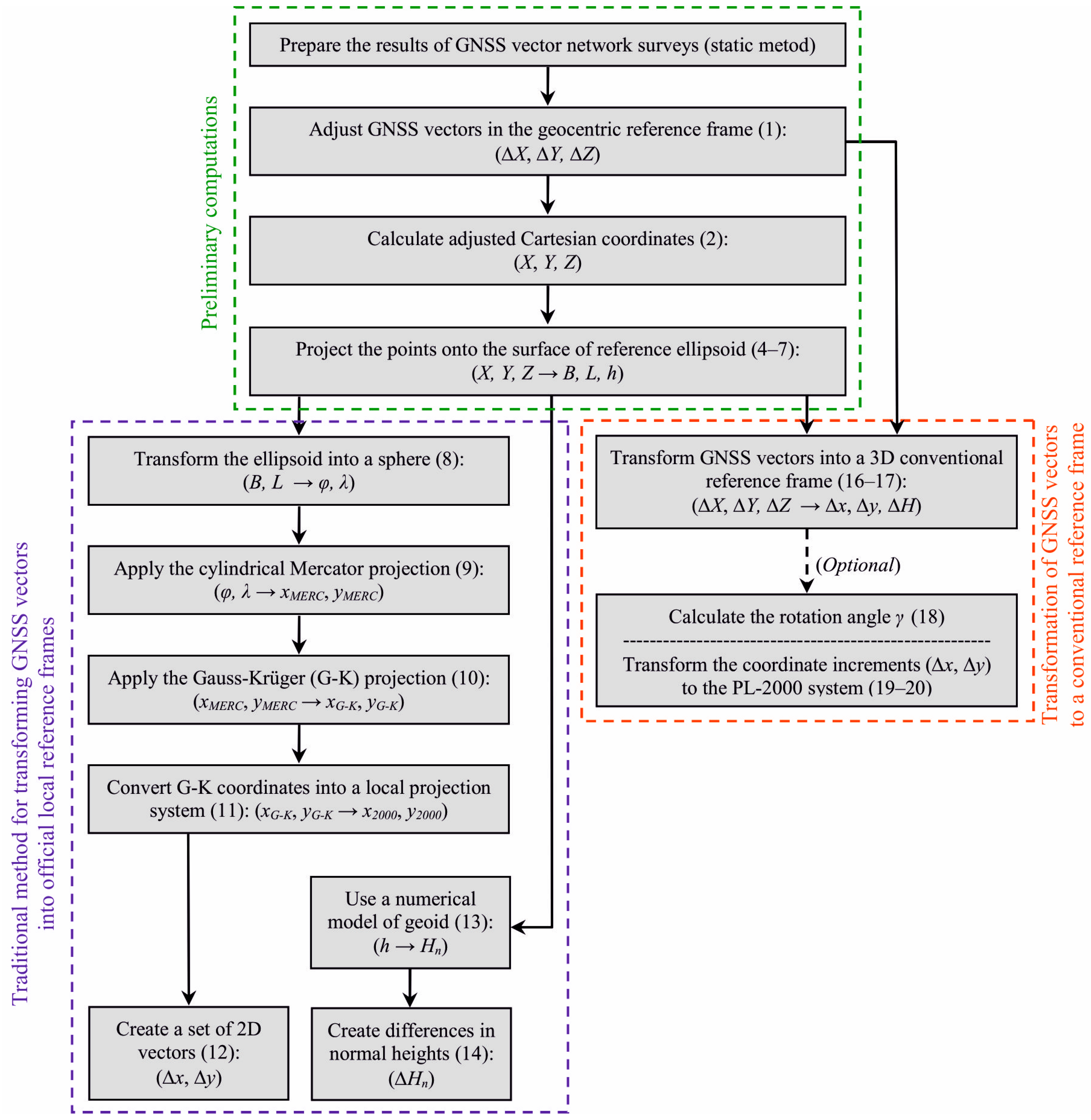

2.3. Diagram of the Computational Procedures

- -

- Preliminary computations (common to both methods);

- -

- Traditional procedure for converting GNSS vectors into official local reference frames;

- -

- Transforming GNSS vectors into the conventional reference frame (the method proposed in this paper).

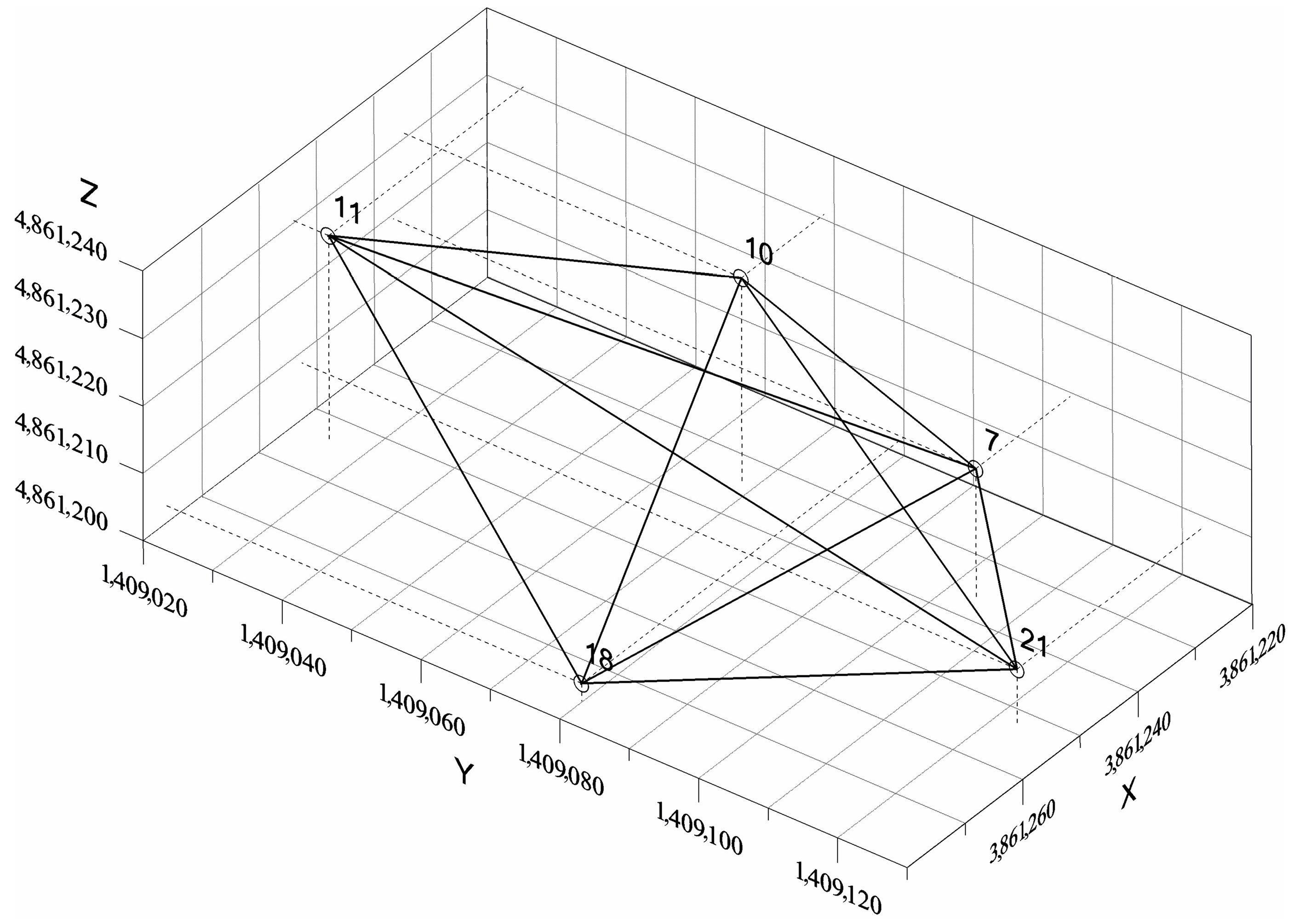

3. Numerical Example (Results and Discussion)

4. Summary and Conclusions

- Simple computation (no need to convert the ellipsoidal height into the orthometric height system using the geoid model or use map projection onto the plane of the official local reference frame);

- The local height difference (ΔH) is free from the impact of the geoid numerical model’s uncertainty;

- Increments of 2D coordinates (Δx, Δy) are free from map projection errors.

- Survey (control network) area limited to about 300 m;

- The calculated height difference (ΔH) does not account for Earth’s curvature (still, for a vector magnitude up to about 300 m, the impact is below the local geoid model error).

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kudrys, J.; Krzyżek, R. Analysis of Coordinates Time Series Obtained Using the NAWGEO Service of the ASG-EUPOS System. Geomat. Environ. Eng. 2011, 5, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Krzyżek, R. Routing corners of building structures—By the method of vector addition—Surveyed with RTN GNSS technology using indirect methods of measurement. Artif. Satel. J. Planet. Geod. 2015, 50, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mszanik, M.; Gargula, T. Satellite leveling as an alternative to classic height measurements for typical engineering problems. Geomat. Landmanag. Landsc. 2024, 4, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusz, J.; Kłos, A.; Grzempowski, P.; Kontny, B. Modelling the Velocity Field in a Regular Grid in the Area of Poland on the Basis of the Velocities of European Permanent Stations. Pure Appl. Geoph. 2014, 171, 809–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudas, D.; Wnek, A. Operation of ASG-EUPOS POZGEO sub-service in the event of failure of reference stations used in the standard solution—Case study. Geomat. Landmanag. Landsc. 2019, 4, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland. Technical Guidelines G-1.12. Satellite Measurements Based on the ASGEUPOS Precise Positioning System—Draft Dated March 1, 2008, with Amendments; Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. (In Polish)

- Acosta, L.E.; De Lacy, M.C.; Ramos, M.I.; Cano, J.P.; Herrera, A.M.; Avilés, M.; Gil, A.J. Displacements study of an earth fill dam based on high precision geodetic monitoring and numerical modeling. Sensors 2018, 18, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryła, R.; Oszczak, S.; Koczot, B.; Szczechowski, B. A concept of using static GPS measurements for determination of vertical and horizontal land deformations in the Main and Old City of Gdansk. Rep. Geod. 2007, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gargula, T. A kinematic model of a modular network as applied for the determination of displacements. Geod. Cartogr. 2009, 58, 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gargula, T. Integrated Modular Networks in the Application for Determination of the Displacements; Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Rolniczego: Krakow, Poland, 2011; p. 473. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kadaj, R. Models, Methods and Computing Algorithms of Kinematic Networks in Geodetic Measurements of Movements and Deformation of Objects; Publishing House of Agricultural University of Krakow: Krakow, Poland, 1998. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Preweda, E. Estymacja Parametrów Kinematycznego Modelu Przemieszczeń (Estimation of Parameters of the Kinematic Displacement Model); Wydawnictwo Naukowe i Dydaktyczne AGH: Kraków, Poland, 2002; p. 110. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Prószyński, W.; Kwaśniak, M. Basics of the Geodetic Assignation of Movements. Concepts and Elements of the Methodology; Publishing House of Warsaw University of Technology: Warszawa, Poland, 2006. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, B.; Al-Bayari, O. Geodetic monitoring of a landslide using conventional surveys and GPS techniques. Surv. Rev. 2007, 39, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, Z.; Kamiński, W. Estimation and Prediction of Vertical Deformations of Random Surfaces, Applying the Total Least Squares Collocation Method. Sensors 2020, 20, 3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadaj, R.; Świętoń, T. GPS postprocessing module in GEONET system. Bull. Milit. Univ. Technol. 2010, 59, 153–161. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kudas, D.; Wnek, A. Validation of the number of tie vectors in post-processing using the method of frequency in a centric cube. Open Geosci. 2020, 12, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecki, K. Contemporary Geodesy; Gall: Katowice, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Leick, A. GPS Satellite Surveying; John Wiley & Sons. Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Seeber, G. Satellite Geodesy; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Wellenhof, B.; Lichtenegger, H.; Collins, J. Global Positioning System: Theory and Practice; Springer: Wien, Austria, 2001; Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-7091-6199-9 (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland. Technical Guidelines G-1.10. Cartographic Projection Formulas and Coordinate System Parameters; Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2001. (In Polish)

- Łyszkowicz, A. Geodetic Systems and Reference Frames; Military Aviation Academy: Dęblin, Poland, 2024. (In Polish)

- Kutoglu, H.S. Direct determination of local coordinates from GPS without transformation. Surv. Rev. 2009, 41, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargula, T. GPS Vector Network Adjustment in a Local System of Coordinates Based on Linear-Angular Spatial Pseudo-Observations. J. Surv. Eng. 2011, 137, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosy, J. Global, Regional and National Geodetic Reference Frames for Geodesy and Geodynamics. Pure Appl. Geoph. 2014, 171, 783–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlibowicki, R.; Krzywicka-Blum, E.; Galas, R.; Borkowski, A.; Osada, E.; Cacoń, S. Advanced Geodesy and Geodetic Astronomy; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1988. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kadaj, R. Transformations between the height reference frames: Kronsztadt’60, PL-KRON86-NH, PL-EVRF2007-NH. J. Civ. Eng. Environ. Archit. 2018, 65, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Krynski, J.; Łyszkowicz, A. Study on choice of global geopotential model for quasi-geoid determination in Poland. Geod. Cartogr. 2005, 54, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Łyszkowicz, A. Geoid in the area of Poland in the author’s investigations. Tech. Sci. Univ. Warm. Mazury Olszt. 2012, 15, 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland. Model of the Valid Quasi-Geoid PL-Geoid2021 in the PL-EVRF2007-NH System; Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/gugik/modele-danych (accessed on 7 October 2025). (In Polish)

- Beluch, J. Detailed Situational and Height Geodetic Networks Determined in a Conventional Spatial System; Zeszyty Naukowe Akademii Górniczo-Hutniczej: Krakow, Poland, 1981; p. 850. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarini, T.; Hermanowski, A.; Gaździcki, J.; Dobrzycka, M.; Laudyn, I. Geodesy—Detailed Geodetic Control Network; PPWK: Warszawa, Poland, 1990. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Regulation of the Council of Ministers in Poland of 15 October 2012 on the National Spatial Reference System; Prime Minister of Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/ (accessed on 7 October 2025). (In Polish)

- Wiśniewski, Z. Adjustment Calculus in Geodesy; Publications of University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn: Olsztyn, Poland, 2005. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ghilani, C.D. Adjustment Computations: Spatial Data Analysis; John Wiley & Sons. Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gargula, T. Adjustment of an Integrated Geodetic Network Composed of GNSS Vectors and Classical Terrestrial Linear Pseudo-Observations. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargula, T. Point position accuracy in a vector GNSS Network and the way it is linked to reference stations. Geomat. Landmanag. Landsc. 2021, 2, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeoNet Geodetic System. AlgoRes-Soft. Available online: https://www.geonet.net.pl/oferta/ (accessed on 7 October 2025). (In Polish).

- Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland. Transpol v.20.6, A Computer Program for Transforming Coordinates and Heights in the National Spatial Reference System; Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography in Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/6ed73b13-f1cd-426c-8e06-4e92014c4dcf (accessed on 7 October 2025). (In Polish)

- Gargula, T.; Gawronek, P. The Helmert transformation: A proposal for the problem of post-transformation corrections. Adv. Geod. Geoinf. 2023, 72, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsakaki, C.; Agatza-Balodimou, A.; Papazissi, K. Geodetic reference frames transformations. Surv. Rev. 2006, 38, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beluch, J. A generalized method for determination of point displacements in control networks, based on the modified method of observation differences. Geod. Cartogr. 1997, 46, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

| Vector Index | Observations (Components of GNSS Vectors) [m] | Mean Errors of Measurement [m] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| from | to | ΔX | ΔY | ΔZ | mΔX | mΔY | mΔZ |

| 1 | 3 | 18.8574 | −46.1353 | −2.5065 | 0.0062 | 0.0052 | 0.0061 |

| 1 | 4 | 26.0581 | −69.9464 | −1.6011 | 0.0068 | 0.0056 | 0.0066 |

| 2 | 1 | −9.1227 | 23.2029 | 0.8991 | 0.0062 | 0.0051 | 0.0061 |

| 2 | 3 | 9.7354 | −22.9314 | −1.6057 | 0.0037 | 0.0032 | 0.0039 |

| 2 | 4 | 16.9362 | −46.7425 | −0.6996 | 0.0036 | 0.0031 | 0.0038 |

| 3 | 4 | 7.2020 | −23.8102 | 0.9088 | 0.0041 | 0.0032 | 0.0032 |

| 5 | 3 | −8.7924 | 47.6362 | −6.0945 | 0.0075 | 0.0058 | 0.0056 |

| 5 | 4 | −1.5898 | 23.8237 | −5.1855 | 0.0066 | 0.0051 | 0.0052 |

| 5 | 7 | −29.2102 | −26.7750 | 29.6711 | 0.0056 | 0.0049 | 0.0059 |

| 5 | 8 | −43.3054 | −40.9754 | 44.7031 | 0.0056 | 0.0049 | 0.0058 |

| 6 | 3 | 5.3467 | 61.6613 | −20.5954 | 0.0047 | 0.0036 | 0.0036 |

| 6 | 4 | 12.5497 | 37.8504 | −19.6865 | 0.0048 | 0.0037 | 0.0038 |

| 6 | 5 | 14.1397 | 14.0259 | −14.5022 | 0.0058 | 0.0051 | 0.0061 |

| 6 | 7 | −15.0700 | −12.7488 | 15.1701 | 0.0043 | 0.0038 | 0.0047 |

| 6 | 8 | −29.1668 | −26.9499 | 30.2007 | 0.0037 | 0.0032 | 0.0040 |

| 7 | 8 | −14.0972 | −14.2010 | 15.0301 | 0.0039 | 0.0034 | 0.0042 |

| Vector Index | Adjusted GNSS Vectors [m] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| from | to | ΔX | ΔY | ΔZ |

| 1 | 2 | 9.1255 | −23.1996 | −0.9019 |

| 2 | 3 | 9.7368 | −22.9292 | −1.6060 |

| 3 | 4 | 7.2019 | −23.8099 | 0.9069 |

| 4 | 5 | 1.5923 | −23.8212 | 5.1854 |

| 5 | 6 | −14.1382 | −14.0270 | 14.5021 |

| 6 | 7 | −15.0709 | −12.7482 | 15.1687 |

| 7 | 8 | −14.0965 | −14.2012 | 15.0313 |

| Point | X [m] | Y [m] | Z [m] | mX [m] | mY [m] | mZ [m] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3,871,848.0173 | 1,345,998.1564 | 4,870,464.0874 | 0.0073 | 0.0062 | 0.0073 |

| 2 | 3,871,857.1428 | 1,345,974.9568 | 4,870,463.1855 | 0.0054 | 0.0047 | 0.0054 |

| 3 | 3,871,866.8796 | 1,345,952.0276 | 4,870,461.5795 | 0.0050 | 0.0042 | 0.0046 |

| 4 | 3,871,874.0815 | 1,345,928.2177 | 4,870,462.4864 | 0.0051 | 0.0043 | 0.0046 |

| 5 | 3,871,875.6738 | 1,345,904.3965 | 4,870,467.6718 | 0.0072 | 0.0058 | 0.0062 |

| 6 | 3,871,861.5356 | 1,345,890.3695 | 4,870,482.1739 | 0.0062 | 0.0051 | 0.0054 |

| 7 | 3,871,846.4647 | 1,345,877.6213 | 4,870,497.3426 | 0.0088 | 0.0076 | 0.0085 |

| 8 | 3,871,832.3682 | 1,345,863.4201 | 4,870,512.3739 | 0.0088 | 0.0076 | 0.0085 |

| KATO | 3,862,992.3806 | 1,332,822.6741 | 4,881,105.4573 | - | - | - |

| KRAW | 3,856,936.1743 | 1,397,750.4815 | 4,867,719.4488 | - | - | - |

| WODZ | 3,896,698.7807 | 1,300,673.7066 | 4,863,029.3737 | - | - | - |

| ZYWI | 3,904,633.3207 | 1,360,191.8920 | 4,840,630.7894 | - | - | - |

| Point No. | Geographic Ellipsoidal Coordinates (WGS84) | Ellipsoidal Height h [m] | Orthometric Height (PL-EVRF2007-NH) Hn [m] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude B [º] | Longitude L [º] | |||

| 1 | 50.1044577593 | 19.1693493783 | 279.8002 | 238.7604 |

| 2 | 50.1044456499 | 19.1690012024 | 279.7508 | 238.7105 |

| 3 | 50.1044248848 | 19.1686537911 | 279.5885 | 238.5477 |

| 4 | 50.1044371169 | 19.1683063863 | 279.6331 | 238.5918 |

| 5 | 50.1045105889 | 19.1679845766 | 279.5595 | 238.5179 |

| 6 | 50.1047180819 | 19.1678642683 | 279.1664 | 238.1252 |

| 7 | 50.1049325987 | 19.1677651230 | 278.9891 | 237.9482 |

| 8 | 50.1051432656 | 19.1676423213 | 278.9908 | 237.9503 |

| Mean | 50.1046337433 | 19.1683208809 | - | - |

| Point No. | 2D Coordinates (PL-2000) | |

|---|---|---|

| x [m] | y [m] | |

| 1 | 5,552,693.2722 | 6,583,648.1303 |

| 2 | 5,552,691.5354 | 6,583,623.2456 |

| 3 | 5,552,688.8370 | 6,583,598.4307 |

| 4 | 5,552,689.8085 | 6,583,573.5587 |

| 5 | 5,552,697.6198 | 6,583,550.4112 |

| 6 | 5,552,720.5623 | 6,583,541.4443 |

| 7 | 5,552,744.3096 | 6,583,533.9792 |

| 8 | 5,552,767.6023 | 6,583,524.8286 |

| Vector Index | Coordinate Differences [m] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| from | to | Δx | Δy | ΔHn |

| 1 | 2 | −1.7368 | −24.8847 | −0.0499 |

| 2 | 3 | −2.6984 | −24.8149 | −0.1628 |

| 3 | 4 | 0.9715 | −24.8720 | 0.0441 |

| 4 | 5 | 7.8113 | −23.1475 | −0.0739 |

| 5 | 6 | 22.9425 | −8.9669 | −0.3927 |

| 6 | 7 | 23.7473 | −7.4651 | −0.1770 |

| 7 | 8 | 23.2927 | −9.1506 | 0.0021 |

| Vector Index | B, L–Point 1 | B, L–Point 4 | B, L–Point 8 | B, L–Mean | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| from | to | Δx | Δy | ΔH | Δx | Δy | ΔH | Δx | Δy | ΔH | Δx | Δy | ΔH |

| 1 | 2 | −1.347 | −24.910 | −0.049 | −1.347 | −24.910 | −0.049 | −1.348 | −24.910 | −0.049 | −1.347 | −24.910 | −0.049 |

| 2 | 3 | −2.310 | −24.855 | −0.162 | −2.310 | −24.855 | −0.162 | −2.310 | −24.855 | −0.162 | −2.310 | −24.855 | −0.162 |

| 3 | 4 | 1.361 | −24.855 | 0.044 | 1.361 | −24.855 | 0.045 | 1.360 | −24.855 | 0.045 | 1.361 | −24.855 | 0.045 |

| 4 | 5 | 8.173 | −23.023 | −0.074 | 8.173 | −23.023 | −0.074 | 8.173 | −23.023 | −0.073 | 8.173 | −23.023 | −0.074 |

| 5 | 6 | 23.081 | −8.607 | −0.393 | 23.081 | −8.607 | −0.393 | 23.081 | −8.607 | −0.393 | 23.081 | −8.607 | −0.393 |

| 6 | 7 | 23.862 | −7.093 | −0.178 | 23.862 | −7.093 | −0.177 | 23.862 | −7.093 | −0.177 | 23.862 | −7.093 | −0.177 |

| 7 | 8 | 23.434 | −8.785 | 0.001 | 23.434 | −8.785 | 0.001 | 23.434 | −8.786 | 0.002 | 23.434 | −8.785 | 0.002 |

| 8 | 1 | −76.254 | 122.127 | 0.811 | −76.253 | 122.128 | 0.810 | −76.251 | 122.129 | 0.808 | −76.253 | 122.128 | 0.809 |

| Azimuth of Direction 8 → 1 Angle of Rotation (19) [gon] | Vector Index | Conventional Reference Frame, Corrected [m] | Deviations from PL-2000 and PL-EVRF2007-NH [m] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| from | to | Δx | Δy | ΔH | δ(Δx) | δ(Δy) | δ(ΔH) | ||

| 1 | 2 | −1.737 | −24.886 | −0.049 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||

| A(U) = 135.5325 | 2 | 3 | −2.699 | −24.816 | −0.162 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | |

| 3 | 4 | 0.972 | −24.873 | 0.045 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | ||

| A(K) = 134.5365 | 4 | 5 | 7.812 | −23.148 | −0.074 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | 6 | 22.943 | −8.967 | −0.393 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| γ = 0.9960 | 6 | 7 | 23.748 | −7.465 | −0.177 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| 7 | 8 | 23.293 | −9.151 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 | ||

| 8 | 1 | −74.333 | 123.306 | 0.809 | 0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 | ||

| Vector Index | Actual (Spatial) Distances [m] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial GNSS Vectors | PL-2000; EVRF2007 | Conventional System | ||

| from | to | |||

| 1 | 2 | 24.946 | 24.945 | 24.946 |

| 2 | 3 | 24.963 | 24.962 | 24.963 |

| 3 | 4 | 24.892 | 24.891 | 24.892 |

| 4 | 5 | 24.431 | 24.430 | 24.431 |

| 5 | 6 | 24.636 | 24.636 | 24.636 |

| 6 | 7 | 24.895 | 24.894 | 24.895 |

| 7 | 8 | 25.026 | 25.026 | 25.026 |

| 8 | 1 | 143.980 | 143.975 | 143.980 |

| Vector Index | Horizontal Distance [m] | Height Difference [m] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement on Site | Map Coordinate System PL-2000 | Conventional Reference Frame | Geometric Levelling | Height Deviation (See Table 6 and Table 8) | |||||

| from | to | d(T) | d(K) | d(K) − d(T) | d(U) | d(U)− d(T) | ΔH(G) | ΔH(EVRF)− ΔH(G) | ΔH(U)− ΔH(G) |

| 1 | 2 | 24.958 | 24.945 | −0.013 | 24.946 | −0.012 | −0.058 | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| 2 | 3 | 24.964 | 24.961 | −0.003 | 24.962 | −0.002 | −0.163 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| 3 | 4 | 24.892 | 24.891 | −0.001 | 24.892 | 0.000 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| 4 | 5 | 24.442 | 24.430 | −0.012 | 24.431 | −0.011 | −0.072 | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| 5 | 6 | 24.637 | 24.633 | −0.004 | 24.633 | −0.004 | −0.399 | 0.006 | 0.006 |

| 6 | 7 | 24.898 | 24.893 | −0.005 | 24.894 | −0.004 | −0.173 | −0.004 | −0.004 |

| 7 | 8 | 25.019 | 25.026 | 0.007 | 25.026 | 0.007 | −0.002 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| 8 | 1 | 143.992 | 143.973 | −0.019 | 143.978 | −0.014 | 0.825 | −0.015 | −0.016 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gargula, T. GNSS Vector Networks in a Local Conventional Reference Frame. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12867. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412867

Gargula T. GNSS Vector Networks in a Local Conventional Reference Frame. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12867. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412867

Chicago/Turabian StyleGargula, Tadeusz. 2025. "GNSS Vector Networks in a Local Conventional Reference Frame" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12867. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412867

APA StyleGargula, T. (2025). GNSS Vector Networks in a Local Conventional Reference Frame. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12867. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412867