2.1. Description of Multi-Component Systems

This study focuses on multi-component systems consisting of components with different failure types, i.e., some components experience discrete (hard) failures, while others undergo degradation (soft) failures. The failure probability or degradation process of these components may be affected by the external environment and operational loads. Moreover, due to factors such as functional dependence, load sharing, and environmental coupling, there may be underlying failure interaction relationships among components.

For components subject to discrete failures, the failure can be represented by a binary state variable, denoted as , where indicates that the component i is functioning normally, and indicates that hard failure has occurred. It is commonly assumed that the failure time follows a probability distribution such as the exponential or Weibull distribution.

For components exhibiting degradation failures, the degradation state is represented by a degradation index

, which can typically be modeled using a multi-state Markov process or stochastic process, such as the Wiener process or gamma process. When

, the component

j is considered to be in a new condition; when

reaches a predefined threshold, the component is regarded as having experienced a soft failure, meaning it can no longer meet functional or performance requirements. Taking the linear Wiener process as an example, the degradation process of component

j is expressed as:

where

is the drift parameter,

is the diffusion parameter, and

denotes standard Brownian motion. The probability density function of

is

2.2. Representation of Component Failure Interactions

In multi-component systems, three types of failure interaction can be derived based on the combination between different component failure types:

Interactions between discrete component failures;

Interaction between degradation-related failures;

Mixed failure interaction between discrete and degradation components.

Bayesian network uses nodes to represent individual components and directed edges to denote the static dependency among components. As a result, it can model the first two types of failure interactions, as well as the influence of discrete component failures on degrading components. Furthermore, DBN extends Bayesian networks to model temporal processes by discretizing the system’s operating timeline into slices and assuming that state transitions between consecutive slices are homogeneous and Markovian [

20]. Meanwhile, PHM is capable of capturing the effects of degrading components on discrete-component failures [

10]. It has also been shown that a PHM can be equivalently represented as a Bayesian network [

21]. Therefore, integrating PHM into the DBN enables the comprehensive characterization of all component failure types and their interactions, as well as the dynamic evolution of failures over time.

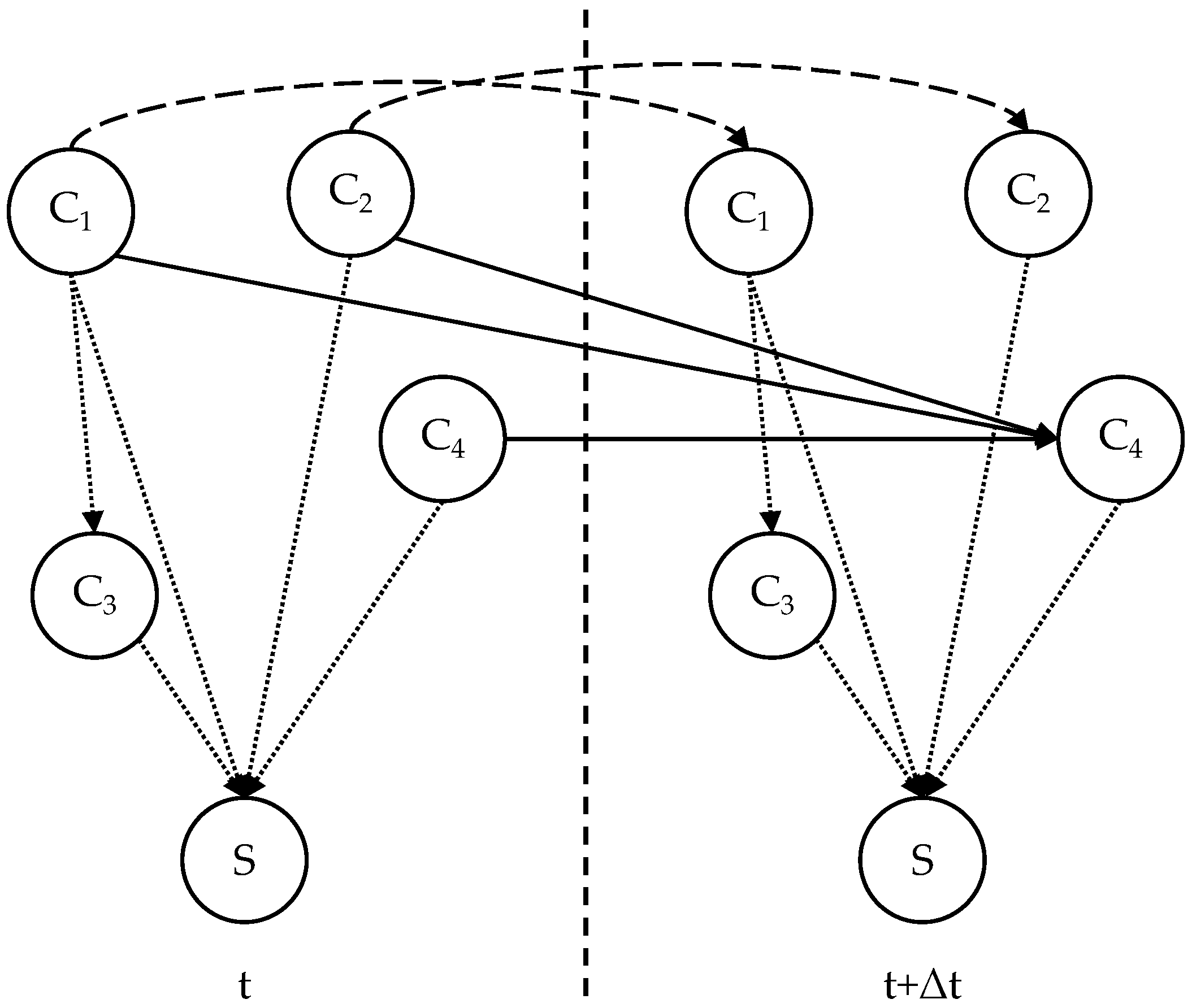

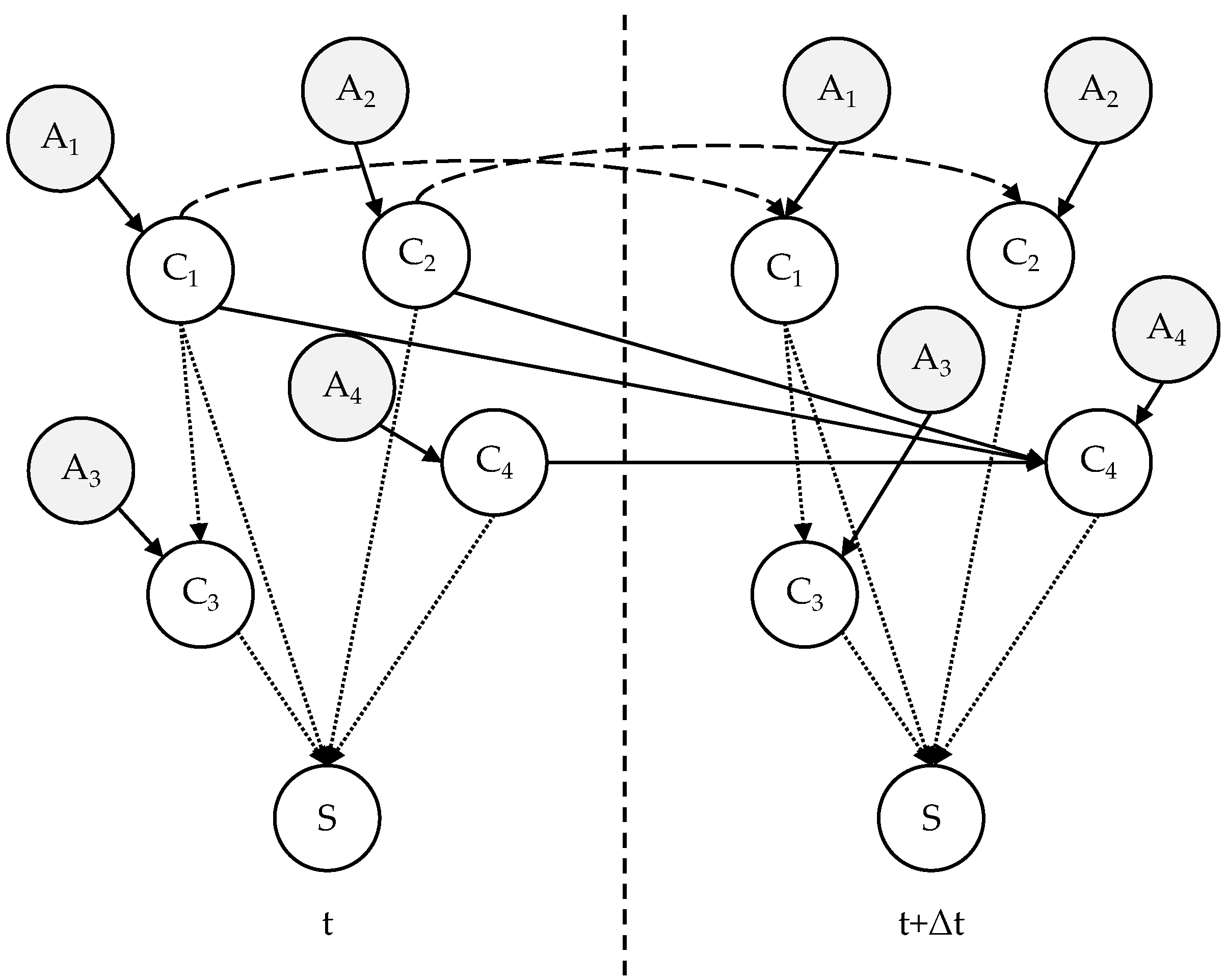

Without loss of generality, a PHM-DBN model is designed as shown in

Figure 1 to illustrate the aforementioned properties. The system includes four components, represented by nodes C

1 to C

4, and a system-level node S. The failure type and state space of each node are defined in

Table 2.

The DBN contains three types of directed edges, representing three different meanings, as detailed below.

Dotted edges between nodes within the same time slice represent static failure dependencies between components, which are quantified using conditional probability tables (CPTs). For example, the directed edge C

1 → C

3 is defined by the CPT in

Table 3, where

and

,

i = 0, 1.

As the failure of any component leads to system malfunction, the CPT of {C

1, C

2, C

3, C

4} → S is defined as follows:

- 2.

Dynamic evolution of single component failure process

Dashed edges connecting the same component across consecutive time slices represent the temporal evolution of its failure process. The time interval Δt is assumed sufficiently small such that no state transition occurs within it. For the discrete component C

1, the CPT of C

1(

t) → C

1(

t + Δ

t) is given in

Table 4, where

R1(·) is the reliability function of C

1.

For the degrading component C

2, its continuous stochastic degradation process is discretized into a multi-state Markov process [

22], and then the Markov transition probability can be represented using CPT. The steps are as follows: Assume that the state space of degradation component

i is divided into

, with a failure threshold is set as

Di. Let

denote the interval width for discretizing the degradation process. For

, if

, the component is considered to be in state

, whereas if

, the component is considered to be in state

, i.e., the failure state, which is the absorbing state of the Markov process. After discretization, the CPT of C

2(

t) → C

2(

t + Δ

t) is given in

Table 5, where

and

is defined in Equation (2).

- 3.

Dynamic failure interactions between components

Solid edges in

Figure 1 connect nodes C

1, C

2, and C

4 across time slices, representing dynamic and mixed failure interactions. These are modeled using a PHM:

where

is the baseline hazard rate of C

4, which depends on the failure distribution of C

4.

is the link function capturing the effect of covariates on the failure process of C

4,

γ is the coefficient and

Z(

t) represents the covariates based on the states of C

1 and C

2. Then, the conditional reliability function of C

4 is:

As the number of covariates and state increases, obtaining an analytical solution for Equation (6) becomes challenging. Therefore, an approximation method is adopted [

23] with the following assumptions:

- (1)

The component state deteriorates continuously over time; that is, the baseline hazard function is nondecreasing.

- (2)

The covariate process is nondecreasing, meaning Z(t + Δt) ≥ Z(t) for any Δt > 0. This is reasonable in most practical scenarios, as covariates in this context correspond to the states of other components. This implies that both the link function and the hazard rate function are also nondecreasing.

The above assumptions align with engineering practice, leading to:

Given the assumption that no state transitions occur within Δ

t when

is sufficiently small, Equations (7) and (8) are very close and build the upper and lower bound of Equation (6). Thus, Equation (6) can be approximated to:

Equation (10) allows the PHM to be converted into CPT. The CPT for the edge {C

1(

t), C

2(

t), C

4(

t)} → C

4(

t + Δ

t) is provided in

Table 6.

2.3. Parameter Learning of the PHM-DBN Model

Since all the above failure models and failure interactions have been transformed into the DBN representation, the parameter learning of the PHM-DBN model essentially involves parameter learning for the DBN model. This includes two aspects: (1) Parameter learning for the component nodes’ failure models; and (2) Parameter learning for the directed edges representing failure interactions, which can be performed independently.

The parameter learning method for each component node’s failure model depends on the component’s failure type and pre-defined failure model.

Table 7 summarizes the required data sources and applicable parameter learning methods. Among these methods, techniques such as Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) and Bayesian estimation are standardized processes in the reliability engineering field, and detailed implementations can be found in references [

24,

25].

As described in

Section 2.2, the three types of directed edges in the model are all converted into CPT. The first type of CPT represents the conditional probabilities of failure states between components. The second type denotes the state transition probabilities of the same node over time. The third type directly transforms the covariate-hazard rate relationship estimated by the PHM into a DBN-compatible CPT, which is the centerpiece of the PHM-DBN coupling and achieves mathematical compatibility between the two models. Thus, the CPT can be derived directly from the PHM parameter learning results without additional parameter estimation.

Table 8 lists the required data sources and available parameter learning methods for these CPTs, which follow standardized procedures in both DBN and PHM research. Since this study focuses on optimal maintenance decision-making, the detailed steps for CPT and PHM parameter learning are not elaborated further and can be referred to in [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].