1. Introduction

The interoperability of heterogeneous industrial devices, constrained by a multitude of proprietary communication protocols, remains a fundamental challenge in realizing the vision of Industry 4.0. Existing research indicates that protocol fragmentation leads to data silos and significantly increases industrial system integration costs. Wang et al. [

1] showed that heterogeneous protocol stacks in manufacturing systems impede the integration of large-scale industrial cyber-physical systems. Afrin et al. [

2] highlighted that insufficient device compatibility exacerbates system integration complexity, particularly in multi-protocol IIoT environments. This lack of compatibility imposes additional burdens on practical deployment. Hazra et al. [

3] further emphasized that the widespread use of proprietary protocols and interfaces by heterogeneous devices in industrial settings results in inconsistent communication semantics, thereby complicating interoperability. For system integrators and plant engineers, configuring and maintaining communication networks and device drivers for numerous Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs), sensors, and actuators requires substantial engineering effort. Dürkop et al. [

4] analyzed the engineering efforts involved in commissioning industrial automation systems. They noted that software-related engineering activities account for 50–60% of the total engineering time, with communication network configuration and process data assignment alone constituting approximately 25% of the total workload. These tasks involve significant complexity, such as the need to use multiple vendor-specific tools and ensure precise matching between device description files and physical components. This “integration tax” directly impedes the agile deployment of advanced applications, from cloud-based control strategies to large-scale sensing networks. While our prior work established a software-defined gateway paradigm [

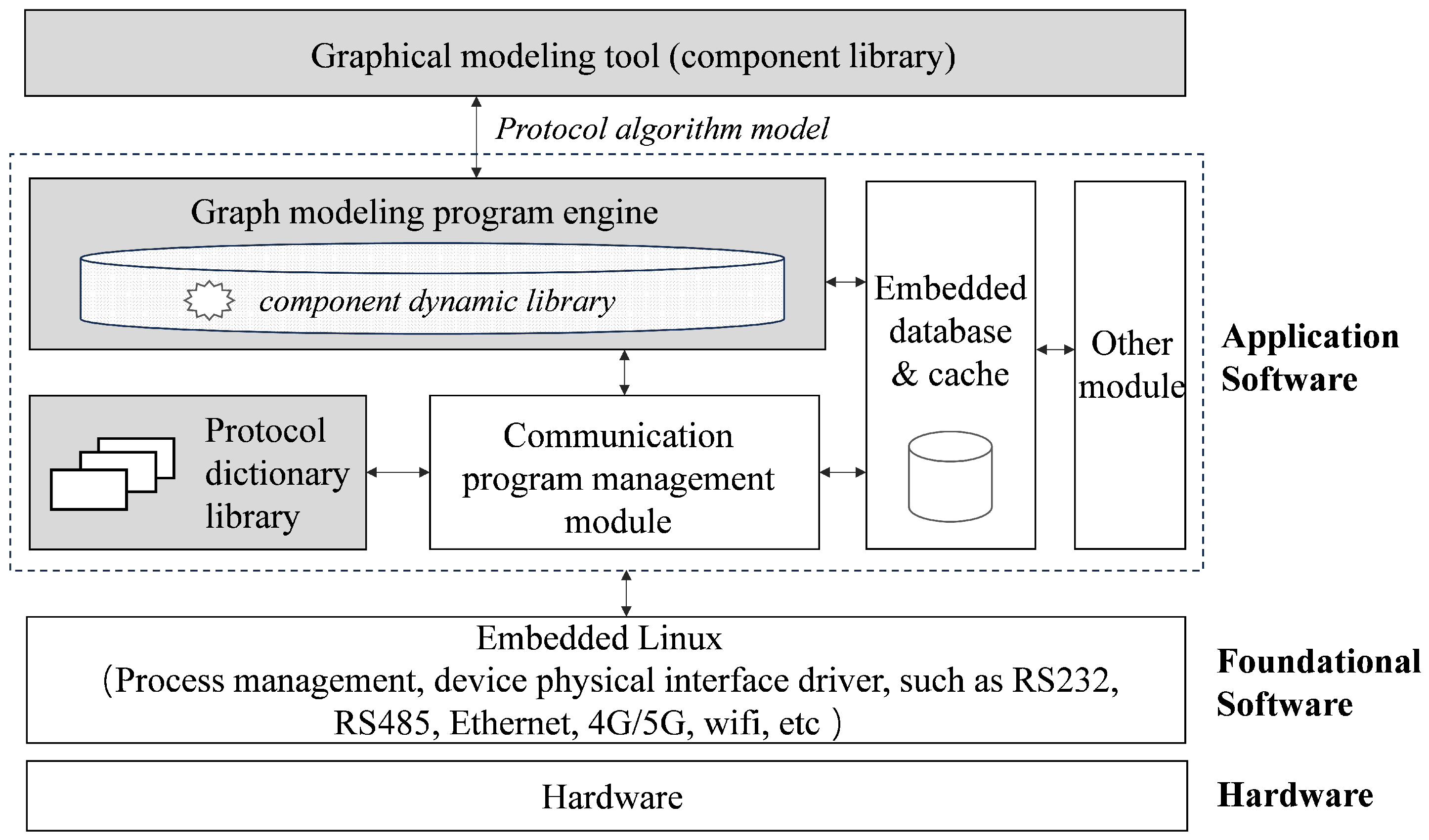

5] that decouples protocol logic from hardware through graphical modeling, the practical realization of this paradigm hinges on a robust and universal core engine. This engine must efficiently translate high-level graphical configurations into reliable, real-time protocol communication capabilities.

Current industrial protocol adaptation methods primarily follow two technical pathways: text-based configuration approaches and modeling approaches based on graphical tools. Text-based methods, represented by structured descriptions, such as eXtensible Markup Language (XML) [

6] and JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) [

7], have been widely adopted in industrial platforms like PI System [

8] and KEPServerEX [

9]. Although offering a degree of flexibility, these methods generally lack deep abstraction of protocol semantics and effective validation mechanisms during the design phase. Issues such as offset deviations and field inconsistencies that arise during configuration often only manifest at runtime, significantly increasing debugging and maintenance costs. Graphical tool-based methods encompass general-purpose visual environments like Node-RED [

10], as well as some modeling techniques inspired by Model-Driven Engineering (MDE) [

11]. While these methods have reduced the usage barrier, their original design focus is primarily on data-flow processing or task logic orchestration. As a result, they struggle to accurately express domain-specific concepts inherent to industrial protocols, such as protocol frame structures, register semantics, and state behaviors. The relevant parsing logic still has to be implemented programmatically via independent nodes, which makes it difficult to meet stringent industrial requirements for determinism, maintainability, and extensibility. Furthermore, the logic constructed by existing tools is mostly static and generally lacks support for runtime modification, flexible adaptation to protocol variants, and online debugging. These limitations become critical in industrial environments characterized by heterogeneous devices and parallel multi-protocol operations.

The above analysis reveals a critical gap in current research; there is an urgent need for an industrial protocol adaptation mechanism that provides unified semantic abstraction, supports intuitive graphical representation, and enables runtime dynamic reconfiguration and debugging. Neither text-based configuration methods nor general-purpose graphical tools can satisfactorily balance the dimensions of protocol semantic modeling, debugging support, runtime reconfigurability, and industrial-grade reliability. To bridge this gap, this paper proposes GMGbox, a graphical modeling-based industrial protocol adaptation engine. By integrating a protocol dictionary, a domain-specific graphical component library, and a cyclically scheduled executor, this engine establishes a unified protocol adaptation mechanism. It thereby achieves protocol semantic abstraction, visual modeling, online debugging, and cycle-driven scan-based execution.

As the core runtime component of the previously proposed gateway architecture, GMGbox is specifically designed to operationalize the software-defined paradigm for industrial communication systems. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

Firstly, a unified protocol dictionary is proposed to provide semantic abstraction and consistent modeling for heterogeneous industrial protocols.

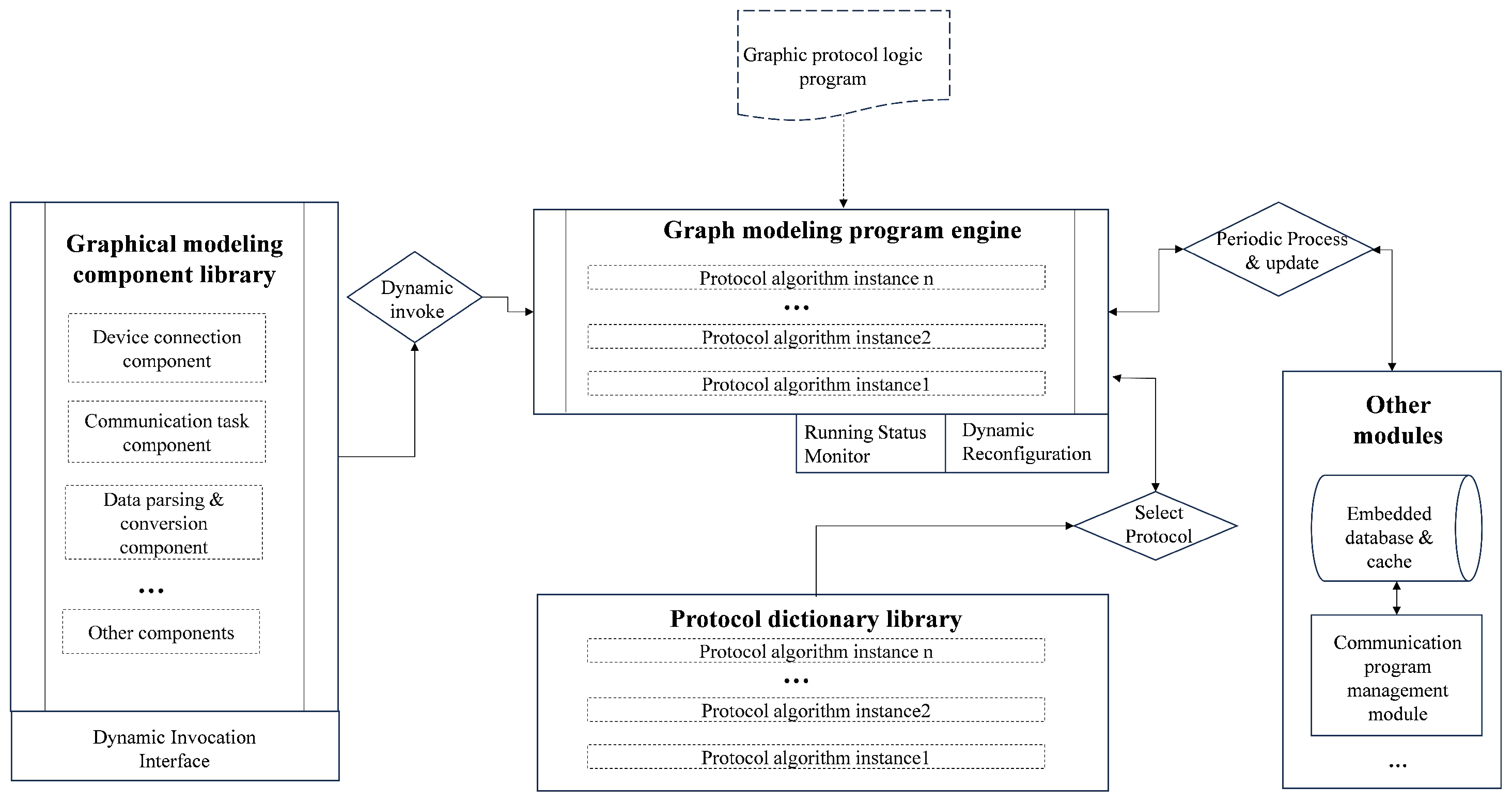

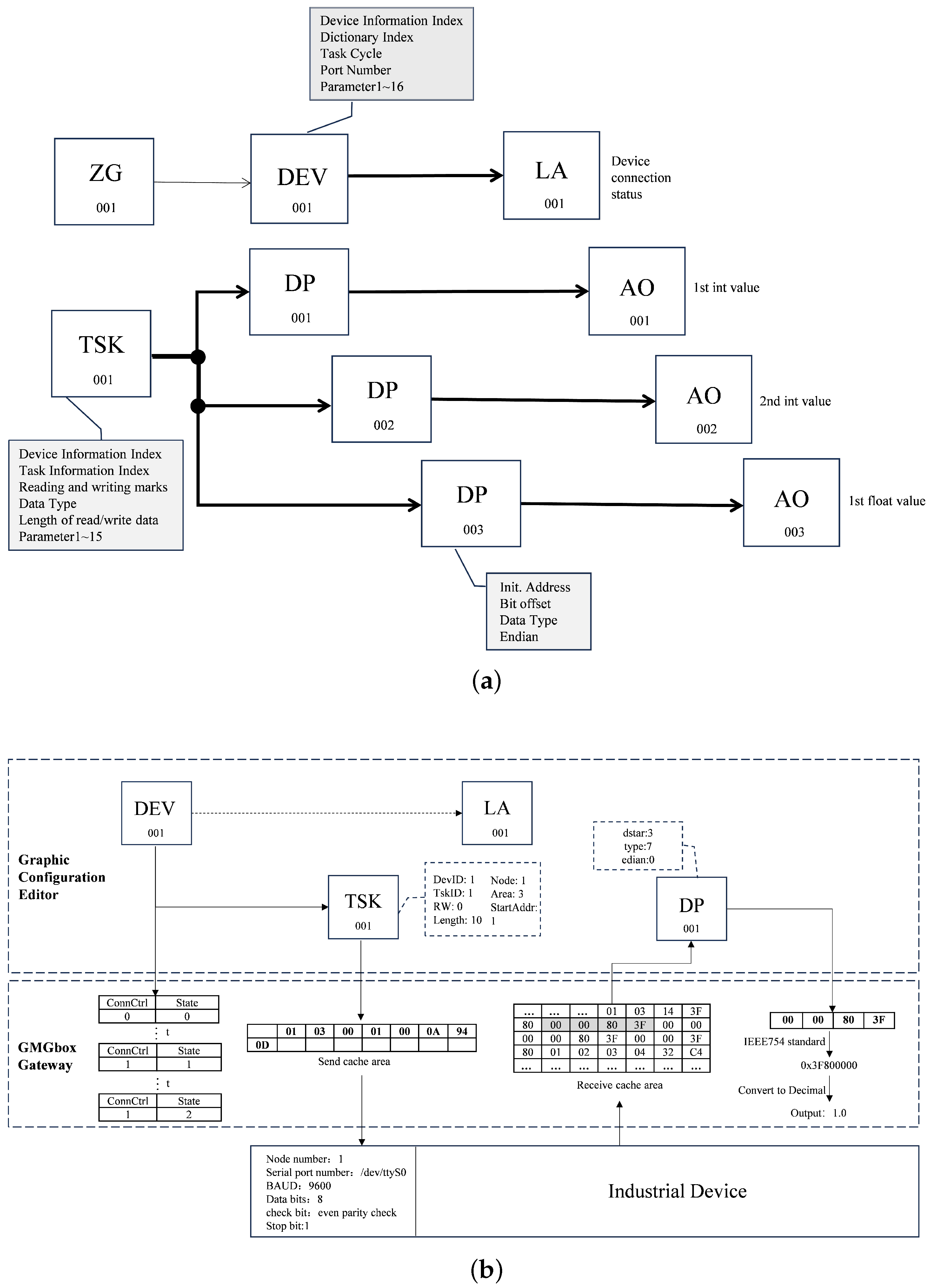

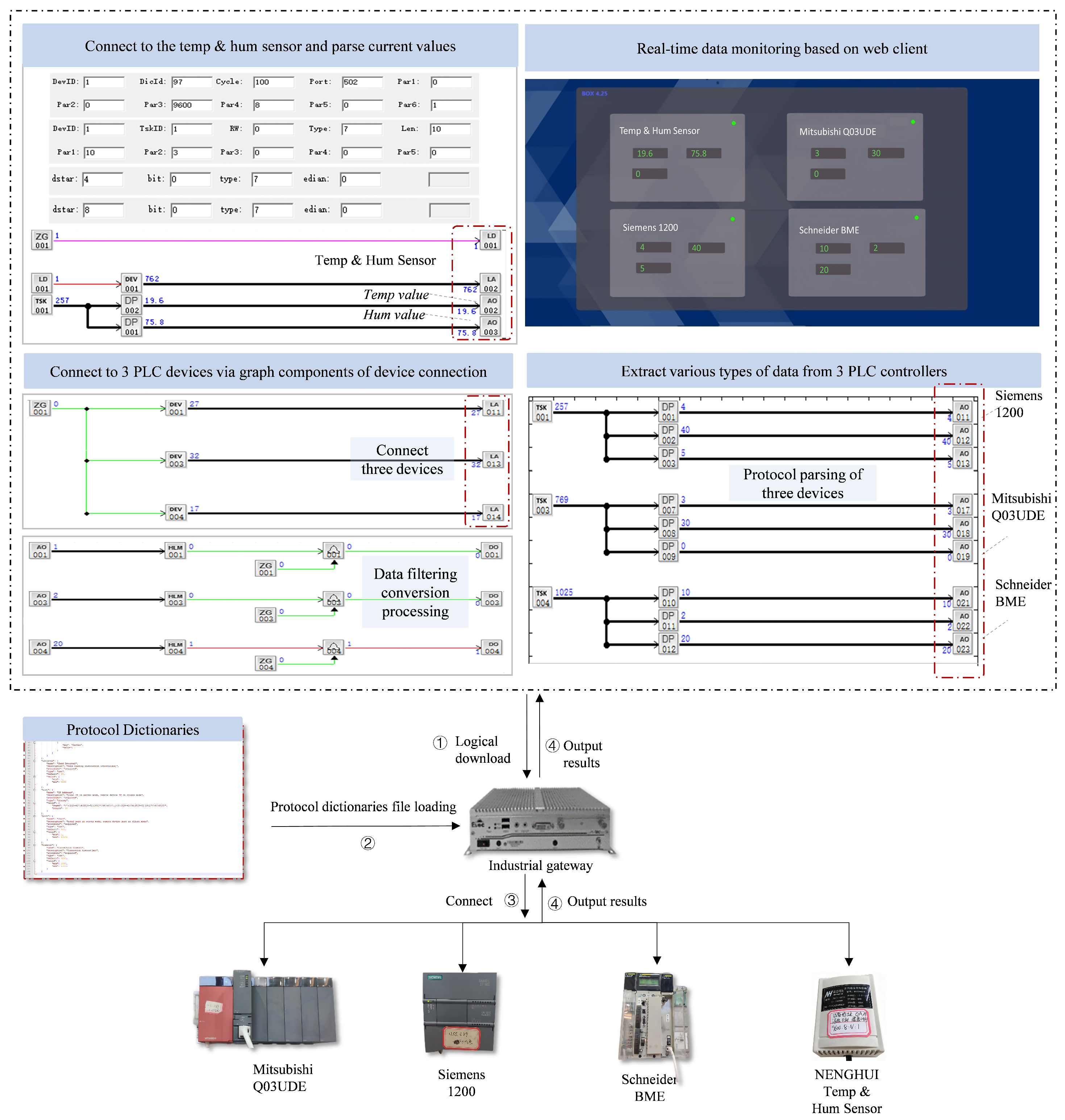

Secondly, a domain-oriented graphical modeling component library is designed, enabling the expression of communication tasks and parsing logic through codeless programming.

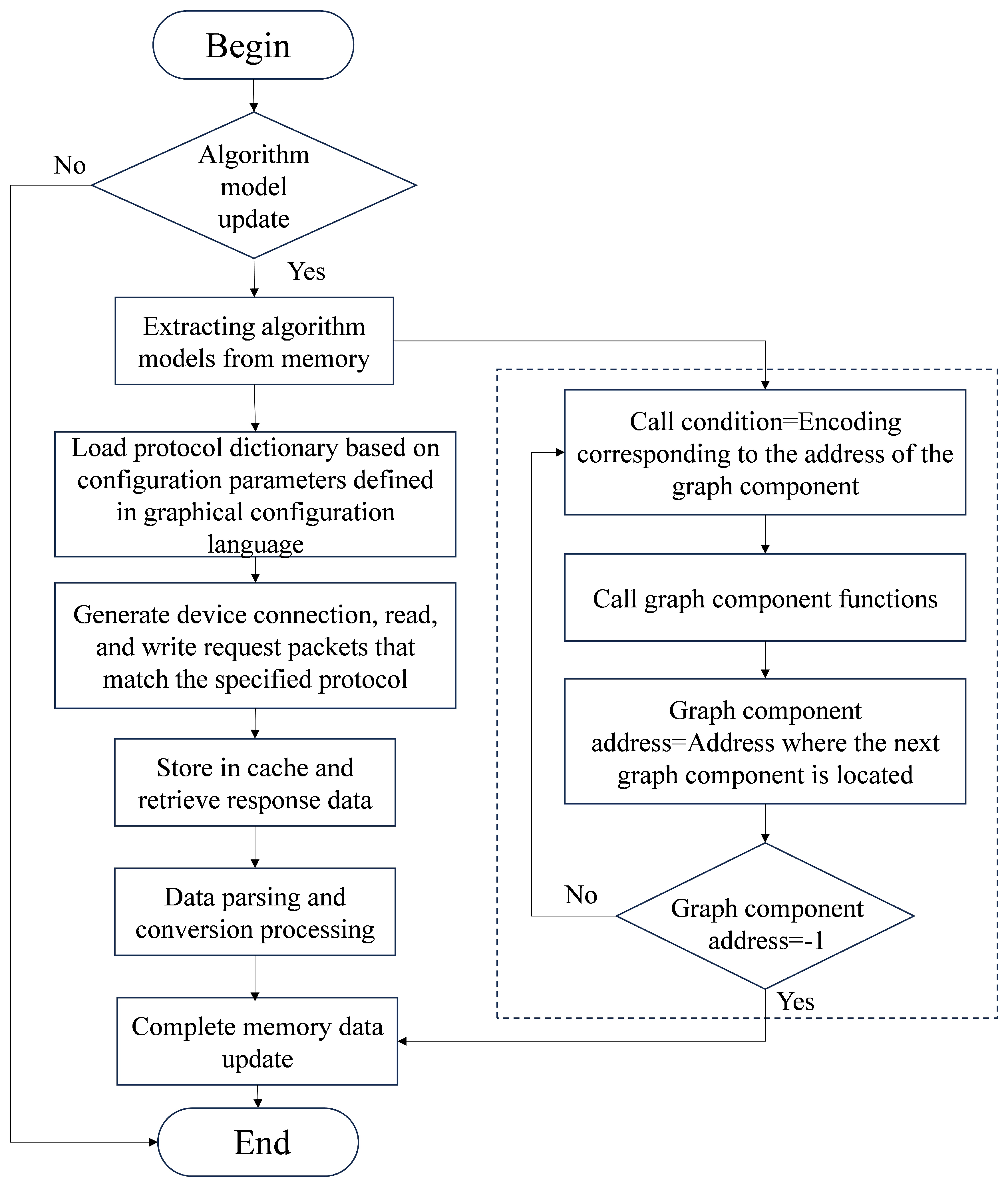

Thirdly, a runtime engine is implemented, which maps graphical models into memory, cyclically executes them, and supports online modification and debugging.

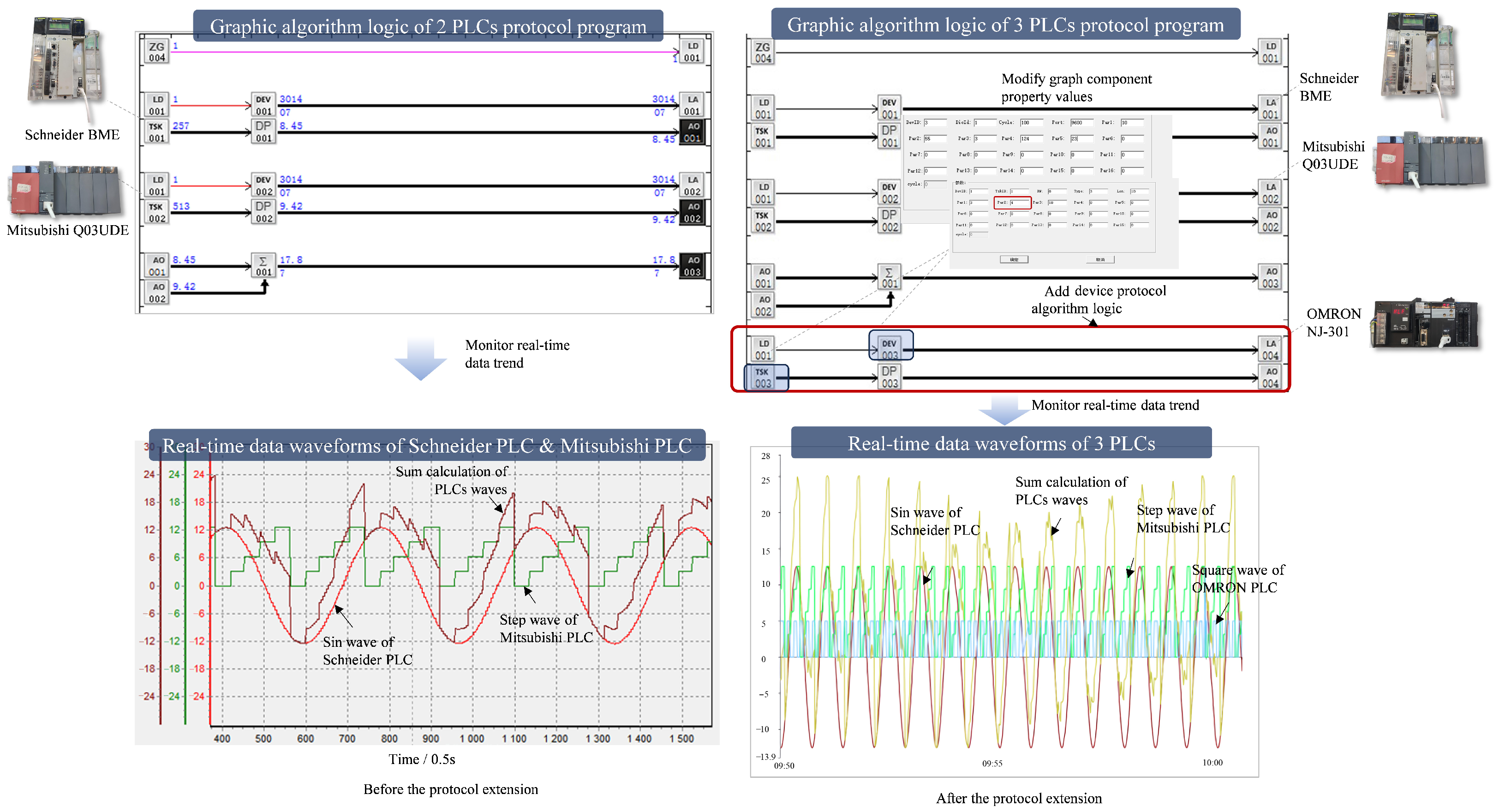

Finally, comprehensive experiments validate that the proposed solution achieves improvements in configurability, maintainability, and extensibility.

Collectively, the GMGbox engine presented in this work addresses these challenges. It fills the critical gap left by existing methods by providing a novel technical pathway that integrates protocol semantic modeling, visual construction, and runtime dynamic extension.

Table 1 summarizes the limitations of existing methods and the corresponding contributions of this work.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the overall architecture of the GMGbox protocol adaptation engine.

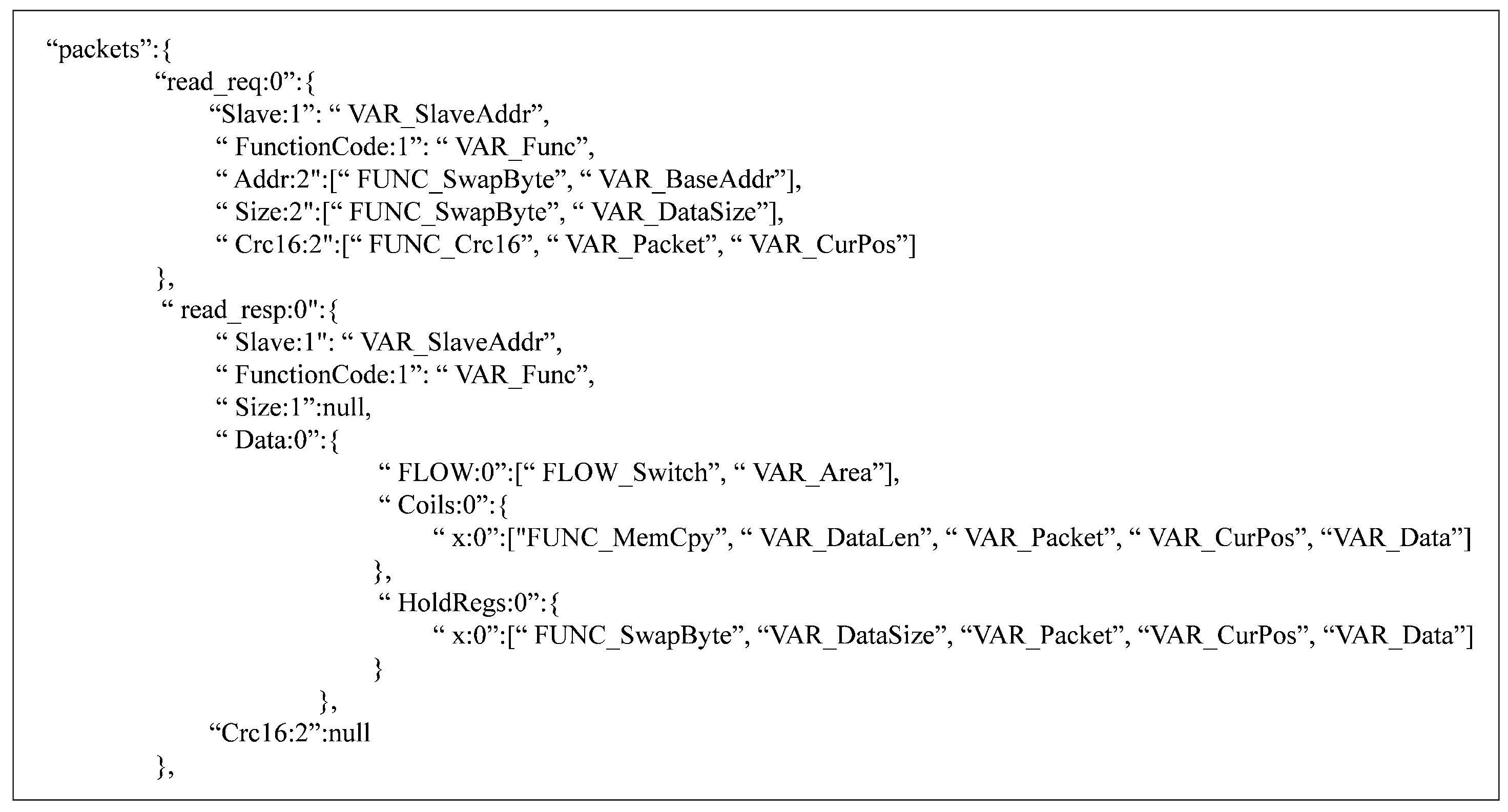

Section 3 provides an in-depth analysis of the engine’s key technologies, including the protocol dictionary model, the graphical component system, and the program execution engine, and demonstrates the complete protocol adaptation process through a concrete configuration example.

Section 4 validates the engine’s multi-protocol processing capability and scalability through experiments.

Section 5 evaluates and discusses the proposed method. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Analysis with General-Purpose Graphical Tools

The architectural advantages of the proposed GMGbox engine can be more clearly understood by contrasting it with the general-purpose graphical tool Node-RED (

Table 7). While Node-RED excels in IoT-oriented integration tasks, its flow-based programming paradigm is not inherently designed for industrial protocol semantics. Protocol details are typically embedded in JavaScript-based function nodes or community-developed custom nodes, making protocol extension dependent on code-level modification.

GMGbox adopts a fundamentally different approach. A unified JSON-based protocol dictionary externalizes protocol semantics, while a domain-specific component library encapsulates key industrial concepts such as device connection, communication tasks, and data parsing. Engineers therefore configure behavior through industrial abstractions (e.g., register access) rather than constructing state machines or byte-level parsing logic inside generic nodes. This reduces configuration complexity and lowers the likelihood of errors.

The execution mechanisms of the two systems also differ. Node-RED relies on an event-driven kernel, with periodic tasks simulated by timer events. GMGbox employs a cycle-driven kernel that performs a scan-based cyclic, execution of graphical models. This aligns is well-suited for implementing periodic device polling and data acquisition.

Dynamic debugging and updating further highlight the contrast. Although Node-RED supports flow-level debugging and hot reloading, the internal logic of protocol-processing nodes cannot be modified at runtime. GMGbox, in contrast, provides component-level monitoring and online parameter adjustment. Updates are written to an in-memory data model, enabling new protocol logic to take effect within a single scan cycle. This capability is essential for industrial environments where interruptions are not acceptable.

Overall, GMGbox shifts protocol adaptation from code-based implementation to a model-driven workflow. As reported in [

5], the unified dictionary, reusable component library, and online-debugging support significantly reduce development and maintenance effort for Modbus RTU/TCP variants. The results demonstrate why domain-specific architectures fundamentally outperform general-purpose graphical tools for industrial protocol/data integration.

5.2. Robustness Comparison with Traditional Extension Methods

GMGbox’s unified extension mechanism can overcome the robustness issues inherent in traditional driver-extension workflows. As summarized in

Table 8, methods based on XML/JSON configuration or schema files still depend on manually written parsing code, making them relatively sensitive to offset errors, boundary mismatches, and incomplete field definitions. Because such tools lack semantic validation and runtime feedback, configuration problems often remain invisible until execution, leading to unreliable behavior. In addition, their extension paths are inconsistent; introducing a new protocol variant typically requires modifying multiple code and schema components, increasing both maintenance effort and the probability of inconsistent behavior across devices.

Flow-based tools also face robustness challenges. Their extensibility relies on custom nodes whose internal parsing logic and timing behavior are not standardized. Under mixed-protocol workloads, this event-driven execution model makes it difficult to guarantee strict fixed intervals or end-to-end latencies, which can increase the risk of timing deviations and inconsistent parsing outcomes. Because node-level behavior is typically implemented as JavaScript functions and depends on the specific runtime environment, debugging and verifying that behavior remains consistent across different deployment environments becomes more challenging.

GMGbox narrows these robustness gaps through a unified and controlled extension workflow. Protocol semantics are externalized into a structured dictionary with consistent field definitions, reducing misalignment errors. Parsing behavior is composed from domain-specific components whose execution semantics are governed by the cycle-driven runtime engine, ensuring timing regardless of protocol variation. Finally, extensions are applied via hot deployment, with updated dictionary entries and component parameters taking effect within one scan cycle. This provides predictable runtime evolution without system interruption.

Collectively, these architectural properties deliver a more reliable, repeatable and extension process compared with traditional configuration-driven or code-based approaches.

5.3. Cross-Industry Transferability Analysis

Although the experimental evaluation in this study focuses on representative industrial communication scenarios, the architectural properties of GMGbox exhibit strong cross-industry transferability. Industrial protocols in sectors such as process control, discrete manufacturing, energy systems, and building automation commonly have similar structural features including register addressing, data frames, cyclic acquisition patterns, and vendor-specific semantic constraints.

GMGbox abstracts these features through its protocol dictionary and encapsulates communication behavior into reusable graphical components. New protocols or device variants can therefore be integrated by updating dictionary templates and component parameters, without modifying the engine kernel. The cycle-driven runtime and memory-resident execution model ensure stable behavior under varying loads, while the separation of semantics, component logic, and scheduling minimizes system dependencies. These characteristics provide effective evidence of the system’s robustness and scalability across heterogeneous industrial environments.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its flexibility and practicality, GMGbox still has several limitations. First, the protocol dictionary requires engineers to manually construct JSON templates based on vendor documentation, and proprietary or insufficiently documented protocols may need additional verification. Second, although GMGbox is compatible with mainstream PLC, DCS, and SCADA architectures, systems with closed communication stacks or vendor-specific transmission mechanisms may require additional adaptation modules. Third, GMGbox does not provide automatic handling of entirely unknown protocols.

Future work will focus on three directions: (1) using machine learning and large language models to automatically extract protocol semantics from vendor documents; (2) further optimizing the transmission-adaptation layer to accommodate specific proprietary communication stacks; and (3) exploring pattern-based semi-automatic modeling techniques to infer field boundaries, length patterns, and encoding rules from sample messages, enhancing adaptability to undocumented or newly introduced protocols.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a systematic description of the design and implementation of the GMGbox protocol adaptation engine based on graphical modeling. As the core implementation of the software-defined interoperability gateway paradigm [

5], GMGbox successfully translates the theoretical advantages of graphical modeling into a practical industrial tool for protocol parsing and conversion.

The main technical innovations of this research include three aspects. Firstly, we propose a unified protocol dictionary model based on JSON templates, which provides structured abstraction of heterogeneous protocol details and significantly reduces the complexity of protocol extension. Secondly, we develop a SAMA-style graphical component system that covers core functions such as device connection, communication tasks, and data parsing, thereby enabling a complete codeless development mechanism for protocol algorithms. Thirdly, we design a universal graphical program-execution engine that supports dynamic loading, real-time processing, and online debugging of protocol algorithms, while maintaining industrial-grade operational reliability.

Experimental evaluations demonstrated that GMGbox can concurrently parse diverse protocols such as MELSEC-QNA, S7-TCP, Modbus TCP/RTU, and FINS/UDP while supporting hot deployment, online debugging, and real-time reconfiguration. These capabilities substantially improve the flexibility and maintainability of industrial data-integration workflows. Overall, GMGbox provides a practical and reusable model-driven solution for industrial interoperability, reducing engineering effort and enabling rapid adaptation to evolving field communication requirements. The architecture demonstrates vast application potential in industrial control scenarios that demand scalable and maintainable protocol integration.