Applying Load–Velocity Profiling to Guide In-Water Resistance Training in an Olympic-Level Swimmer: A Case Study

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Resisted Swimming Intervention

- Velocity decrement of <10%: technical competency;

- Velocity decrement of 10–30%: speed-strength;

- Velocity decrement of 30–40%: power;

- Velocity decrement of 40–70%: strength-speed.

2.2.2. Load–Velocity Profiling

2.2.3. Competition Performance

2.2.4. Training Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

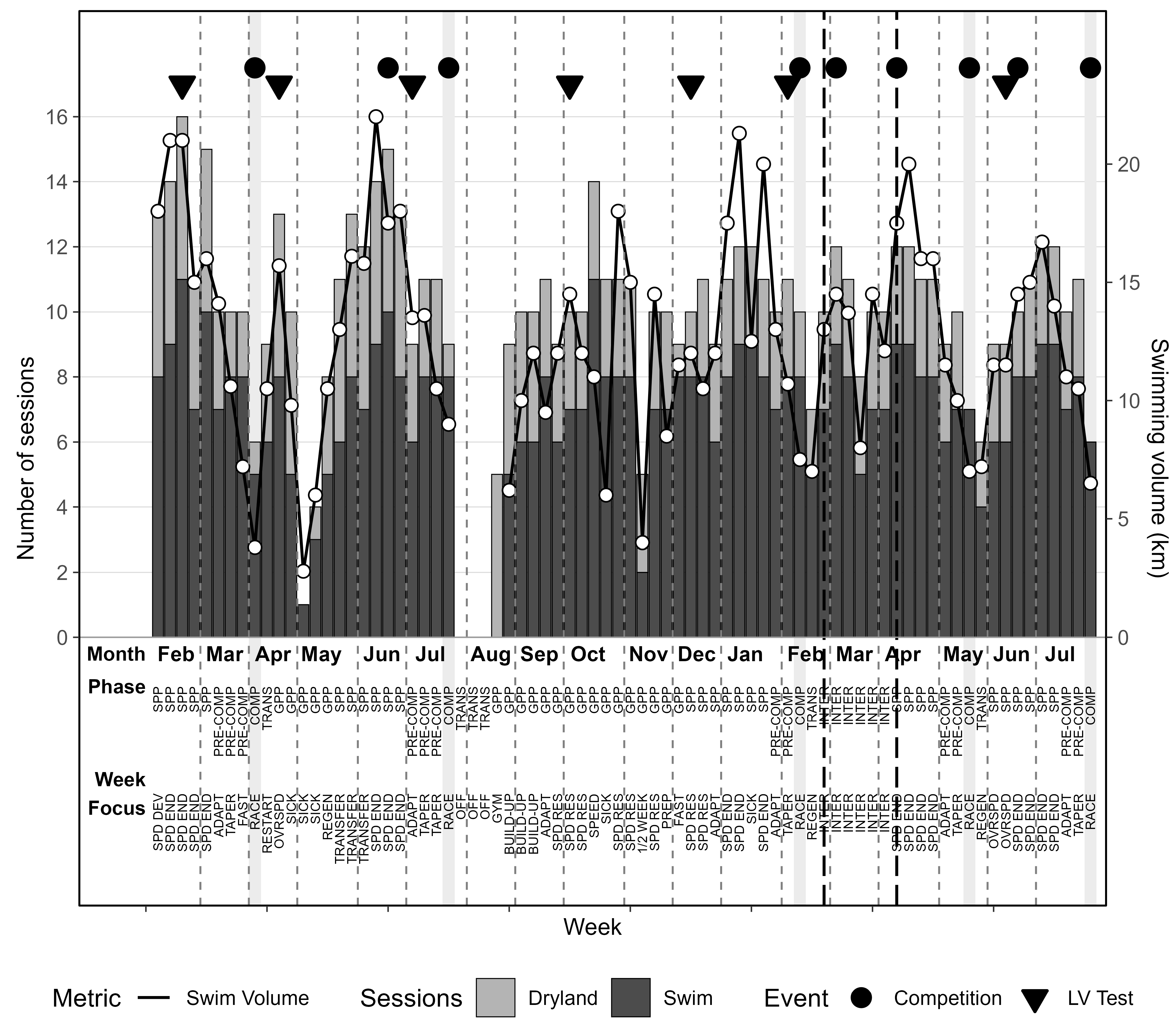

3.1. Resisted Swimming Intervention

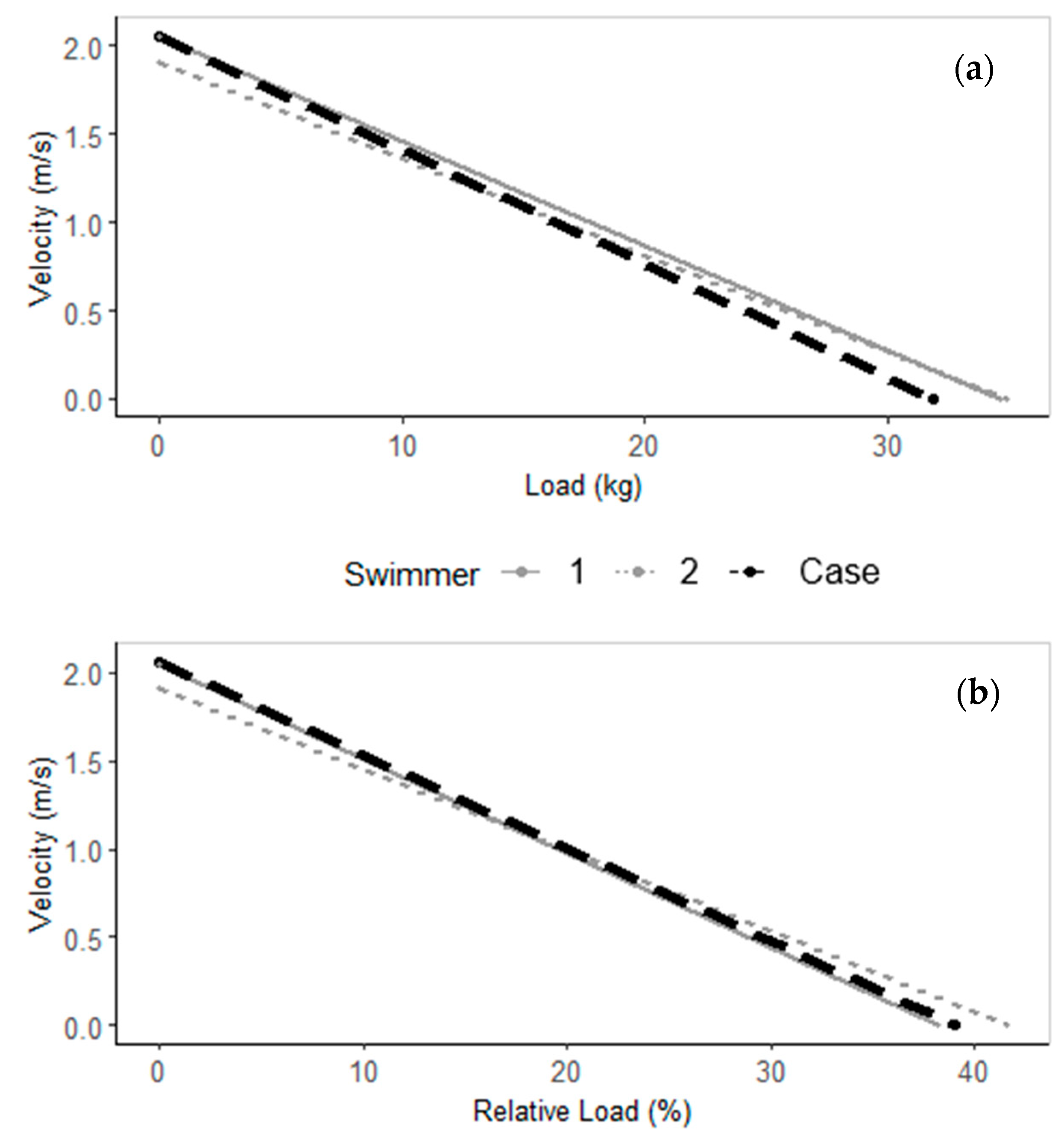

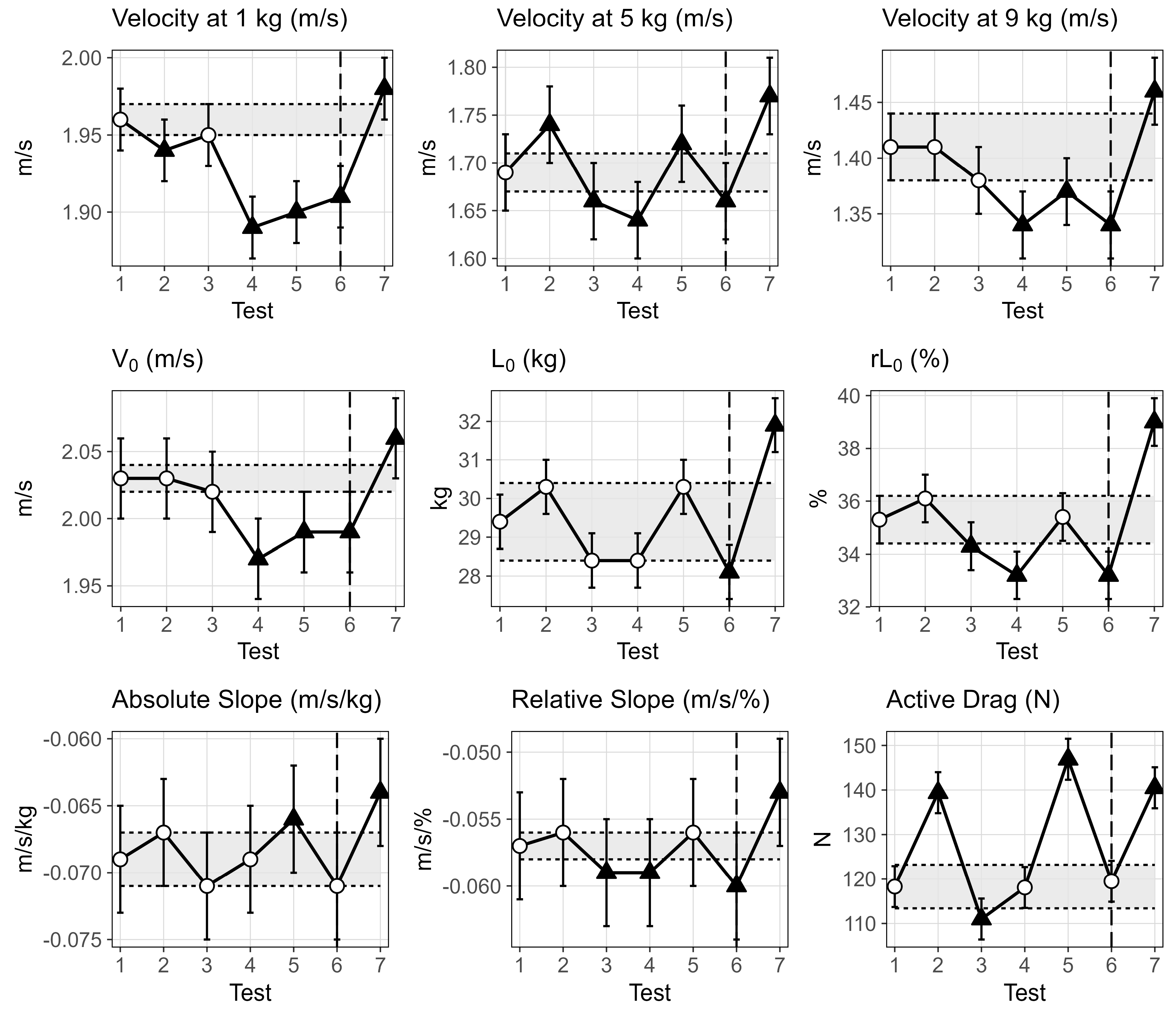

3.2. LV Profiling

- Velocity at 1 kg, 1.96 m/s;

- Velocity at 5 kg, 1.69 m/s;

- Velocity at 9 kg, 1.41 m/s;

- V0, 2.03 m/s;

- L0, 29.4 kg;

- rL0, 35.3%;

- Absolute slope, −0.069 m/s/kg;

- Relative slope, −0.057 m/s/%;

- Active drag, 118.3 N.

3.3. Competition Performance

3.4. Training Overview

4. Discussion

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- The speed of each repetition was monitored in real time to maximise athlete intent and allow adjustments of resistance to ensure the athlete is training within the defined adaptation zone. Resistance was prescribed in “bucket” increments to support real-world applicability while coach monitoring allowed for within-session adjustments based on fatigue or performance.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Active drag |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| GPP | General preparation phase |

| L0 | Maximal theoretical load |

| LV | Load–velocity |

| rL0 | Maximal theoretical load relative to body mass |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SDdiff | Standard deviation of change scores |

| SPP | Specific preparation phase |

| SWC | Smallest worthwhile change |

| TE | Typical error |

| V0 | Maximal swim velocity |

Appendix A

| Jump Variable | Start of Observation | End of Observation | Percentage Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentric Impulse (N.s) | 265 ± 3 | 257 ± 3 | −2.9 |

| Contraction Time (ms) | 683 ± 15 | 738 ± 3 | +8.1 |

| Countermovement Depth (cm) | 34.9 ± 0.7 | 47.3 ± 3.1 | +35.7 |

| Jump Height (cm) | 50.0 ± 1.1 | 50.7 ± 0.9 | +1.4 |

| Peak Velocity (m/s) | 3.25 ± 0.03 | 3.28 ± 0.04 | +0.9 |

| Relative Mean Force (N/kg) | 22.8 ± 0.1 | 21.8 ± 0.3 | −4.5 |

| Relative Peak Power (W/kg) | 67.4 ± 1.0 | 67.1 ± 1.7 | −0.4 |

| RSI-Modified | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.04 | −2.2 |

| Exercise | Start of Observation—1RM (kg) | End of Observation—1RM (kg) | Percentage Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Back Squat | 150 | 165 | +10.0 |

| Bench Press | 110 | 115 | +4.5 |

| Chin Up | 60 | 67 | +11.7 |

References

- Long-Course World Records. Available online: https://www.olympics.com/en/news/swimming-long-course-world-records (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Paris 2024 Men’s 50 m Freestyle Results. Available online: https://www.olympics.com/en/olympic-games/paris-2024/results/swimming/men-50m-freestyle (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Fastest Swims on the Biggest Stage: LA28 Welcomes New 50 m Events. Available online: https://www.worldaquatics.com/news/4246119/swimming-olympics-sports-programme-new-events-50m-backstroke-breaststroke-butterfly-los-angeles-2028-la28-ioc-executive-board (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Simbaña-Escobar, D.; Hellard, P.; Seifert, L. Modelling Stroking Parameters in Competitive Sprint Swimming: Understanding Inter- and Intra-Lap Variability to Assess Pacing Management. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2018, 61, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonjo, T.; Olstad, B.H. Race Analysis in Competitive Swimming: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, R.; Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; Barbosa, T.M.; López-Contreras, G.; Morales-Ortíz, E.; Gay, A.; López-Belmonte, Ó.; González-Ponce, Á.; Cuenca-Fernández, F. Are the 50 m Race Segments Changed From Heats to Finals at the 2021 European Swimming Championships? Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 797367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.E.; Barbosa, T.M.; Silva, A.J.; Veiga, S.; Marinho, D.A. Profiling of Elite Male Junior 50 m Freestyle Sprinters: Understanding the Speed-time Relationship. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2022, 32, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slawson, S.E.; Conway, P.P.; Cossor, J.; Chakravorti, N.; West, A.A. The Categorisation of Swimming Start Performance with Reference to Force Generation on the Main Block and Footrest Components of the Omega OSB11 Start Blocks. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tor, E.; Pease, D.L.; Ball, K.A. Characteristics of an Elite Swimming Start. In Proceedings of the Biomechanics and Medicine in Swimming, Canberra, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2014; pp. 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, D.; Born, D.-P.; Singh, N.B.; Oberhofer, K.; Carradori, S.; Sinistaj, S.; Lorenzetti, S. Key Performance Indicators and Leg Positioning for the Kick-Start in Competitive Swimmers. Sports Biomech. 2023, 22, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, J.E.; Marinho, D.A.; Arellano, R.; Barbosa, T.M. Start and Turn Performances of Elite Sprinters at the 2016 European Championships in Swimming. Sports Biomech. 2019, 18, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorontsov, A. Strength and Power Training in Swimming. In World Book of Swimming: From Science to Performance; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 313–343. [Google Scholar]

- Maglischo, E. Swimming Fastest; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Muniz-Pardos, B.; Gomez-Bruton, A.; Matute-Llorente, A.; Gonzalez-Aguero, A.; Gomez-Cabello, A.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Casajus, J.A.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G. Swim-Specific Resistance Training: A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2875–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, E.; Harrison, A.J.; Lyons, M. The Impact of Resistance Training on Swimming Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2285–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.B.; Pendergast, D.R. Relationships of Stroke Rate, Distance per Stroke, and Velocity in Competitive Swimming. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1979, 11, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, D.B.; Sharp, R.L. Physical and Energy Requirements of Competitive Swimming Events. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweetenham, B.; Atkinson, J.D. Championship Swim Training; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, F.J.; Comyns, T.M.; Warrington, G.D. Quality Versus Quantity Debate in Swimming: Perceptions and Training Practices of Expert Swimming Coaches. J. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 57, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nugent, F.J.; Comyns, T.M.; Burrows, E.; Warrington, G.D. Effects of Low-Volume, High-Intensity Training on Performance in Competitive Swimmers: A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushall, B.S. Swimming Energy Training in the 21st Century: The Justification for Radical Changes. Swim. Sci. Bull. 2011, 39, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Salo, D.; Riewald, S.A. Complete Conditioning for Swimming; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, S.; Gaoua, N.; Johnston, M.J.; Cooke, K.; Girard, O.; Mileva, K.N. Training Regimes and Recovery Monitoring Practices of Elite British Swimmers. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2019, 18, 577–585. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, T.M.; Costa, M.J.; Marinho, D.A. Proposal of a Deterministic Model to Explain Swimming Performance. Int. J. Swim. Kinet. 2013, 2, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, E.; Harrison, A.J.; Lyons, M. Dry-Land Resistance Training Practices of Elite Swimming Strength and Conditioning Coaches. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 2592–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz-Pardos, B.; Gomez-Bruton, A.; Matute-Llorente, A.; Gonzalez-Aguero, A.; Gomez-Cabello, A.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Casajus, J.A.; Vicente-Rodriguez, G. Nonspecific Resistance Training and Swimming Performance: Strength or Power? A Systematic Review. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 1162–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K.; Keiner, M.; Fuhrmann, S.; Nimmerichter, A.; Haff, G.G. Strength Training in Swimming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, R.U.; Jones, J.; Kraemer, W.J.; Wardle, H. Strength and Power Training of Australian Olympic Swimmers. Strength Cond. J. 2002, 24, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.; Cree, J.; Read, P.; Chavda, S.; Edwards, M.; Turner, A. Strength and Conditioning for Sprint Swimming. Strength Cond. J. 2013, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, F.J.; Comyns, T.M.; Warrington, G.D. Strength and Conditioning Considerations for Youth Swimmers. Strength Cond. J. 2018, 40, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.; Kerr, S.; Bowmaker, D.; Gomez, J.-F. A Swim-Specific Shoulder Strength and Conditioning Program for Front Crawl Swimmers. Strength Cond. J. 2019, 41, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fone, L.; van den Tillaar, R. Effect of Different Types of Strength Training on Swimming Performance in Competitive Swimmers: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telles, T.; Barbosa, A.C.; Campos, M.H.; Andries, O. Effect of Hand Paddles and Parachute on the Index of Coordination of Competitive Crawl-Strokers. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grznar, L.; Macejkova, Y.; Labudova, J.; Polakovicova, M.; Putala, M.; Henrich, K. Effect of Resistance Training with Parachutes on Power and Speed Development in a Group of Competitive Swimmers. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2018, 18, 787–791. [Google Scholar]

- Valkoumas, I.; Gourgoulis, V.; Aggeloussis, N.; Antoniou, P. The Influence of an 11-Week Resisted Swim Training Program on the Inter-Arm Coordination in Front Crawl Swimmers. Sports Biomech. 2020, 22, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourgoulis, V.; Valkoumas, I.; Boli, A.; Aggeloussis, N.; Antoniou, P. Effect of an 11-Week In-Water Training Program With Increased Resistance on the Swimming Performance and the Basic Kinematic Characteristics of the Front Crawl Stroke. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coloretti, V.; Fantozzi, S.; Gatta, G.; Bonifazi, M.; Zamparo, P.; Cortesi, M. Quantifying Added Drag in Swimming With Parachutes: Implications for Resisted Swimming Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2025, 39, e701–e705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragunas, A.J.; Dickey, J.P.; Nolte, V.W. The Effect of Drag Suit Training on 50 m Freestyle Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2012, 26, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girold, S.; Calmels, P.; Maurin, D.; Milhau, N.; Chatard, J.C. Assisted and Resisted Sprint Training in Swimming. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2006, 20, 547–554. [Google Scholar]

- Girold, S.; Maurin, D.; Dugué, B.; Chatard, J.C.; Millet, G. Effects of Dry-Land vs. Resisted- and Assisted-Sprint Exercises on Swimming Sprint Performances. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Papoti, M.; Da Silva, A.S.R.; Kalva-Filho, C.A.; Araujo, G.G.; Santiago, V.; Martins, L.E.B.; Cunha, S.A.; Gobatto, C.A. Tethered Swimming for the Evaluation and Prescription of Resistance Training in Young Swimmers. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shdoukhi, K.A.S.; Petersen, C.; Clarke, J. Three Weeks of Combined Resisted and Assisted in-Water Training for Adolescent Sprint Backstroke Swimmin g: A Case Study. Hum. Mov. 2022, 23, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourgoulis, V.; Aggeloussis, N.; Vezos, N.; Kasimatis, P.; Antoniou, P.; Mavromatis, G. Estimation of Hand Forces and Propelling Efficiency during Front Crawl Swimming with Hand Paddles. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gourgoulis, V.; Aggeloussis, N.; Kasimatis, P.; Vezos, N.; Antoniou, P.; Mavromatis, G. The Influence of Hand Paddles on the Arm Coordination in Female Front Crawl Swimmers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.C.; Ferreira, T.H.N.; Leis, L.V.; Gourgoulis, V.; Barroso, R. Does a 4-Week Training Period with Hand Paddles Affect Front-Crawl Swimming Performance? J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Plaza, D.; Alacid, F.; López-Miñarro, P.A.; Muyor, J.M. The Influence of Different Hand Paddle Size on 100-m Front Crawl Kinematics. J. Hum. Kinet. 2012, 34, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunokawa, T.; Tsuno, T.; Mankyu, H.; Takagi, H.; Ogita, F. The Effect of Paddles on Pressure and Force Generation at the Hand during Front Crawl. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2018, 57, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, A.C.; de Souza Castro, F.; Dopsaj, M.; Cunha, S.A.; Júnior, O.A. Acute Responses of Biomechanical Parameters to Different Sizes of Hand Paddles in Front-Crawl Stroke. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naczk, M.; Lopacinski, A.; Brzenczek-Owczarzak, W.; Arlet, J.; Naczk, A.; Adach, Z. Influence of Short-Term Inertial Training on Swimming Performance in Young Swimmers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2017, 17, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, K.; Brammer, C.L.; Sossong, T.D.; Abe, T.; Stager, J.M. In-Water Resisted Swim Training for Age-Group Swimmers: An Evaluation of Training Effects. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 30, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravé, J.M.G.; Lega-Rrese, A.; González-Mohíno, F.; Yustres, I.; Barragán, R.; De Asís Fernández, F.; Juárez, D.; Arroyo-Toledo, J.J. The Effects of Two Different Resisted Swim Training Load Protocols on Swimming Strength and Performance. J. Hum. Kinet. 2018, 64, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Fernández, F.; Gay, A.; Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; Arellano, R. The Effect of Different Loads on Semi-Tethered Swimming and Its Relationship with Dry-Land Performance Variables. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2020, 20, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Fernández, F.; Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; Arellano, R. Strength-Velocity Relationship of Resisted Swimming: A Regression Analysis. ISBS Proc. Arch. 2020, 38, 388. [Google Scholar]

- Odráška, L.; Krč, H.; Grznár, Ľ.; Čillík, I. Effect of Resistance Isokinetic Training on Power and Speed Development in a Group of Competitive Swimmers. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2020, 20, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, H.; Vervoorn, K. Effects of Specific High Resistance Training in the Water on Competitive Swimmers. Int. J. Sports Med. 1990, 11, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, R.; Kennedy, R.; McCabe, C. Sex-Specific Relationships between Sprint Swim Performance and Tethered Swimming in High-Performance Swimmers. Sports Biomech. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, R.; Kennedy, R.; Nevill, A.M.; McCabe, C. A Comparison of Three Methods of Semi-Tethered Profiling in Front Crawl Swimming: A Reliability Study. J. Sports Sci. 2025, 43, 1425–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonjo, T.; Njøs, N.; Eriksrud, O.; Olstad, B.H. The Relationship Between Selected Load-Velocity Profile Parameters and 50 m Front Crawl Swimming Performance. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 625411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonjo, T.; Eriksrud, O.; Papoutsis, F.; Olstad, B.H. Relationships between a Load-Velocity Profile and Sprint Performance in Butterfly Swimming. Int. J. Sports Med. 2020, 41, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstad, B.H.; Hunger, L.; Ljødal, I.; Ringhof, S.; Gonjo, T. The Relationship between Load-Velocity Profiles and 50 m Breaststroke Performance in National-Level Male Swimmers. J. Sports Sci. 2024, 42, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olstad, B.H.; Gonjo, T.; Njøs, N.; Abächerli, K.; Eriksrud, O. Reliability of Load-Velocity Profiling in Front Crawl Swimming. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 574306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; López-Belmonte, Ó.; Gay, A.; Cuenca-Fernández, F.; Arellano, R. A New Model of Performance Classification to Standardize the Research Results in Swimming. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2023, 23, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, R.; Kennedy, R.; McCabe, C. Longitudinal Monitoring of Load-Velocity Variables in Preferred-Stroke and Front-Crawl with National and International Swimmers. Front. Sports Act. Living 2025, 7, 1585319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonjo, T.; Olstad, B.H. Reliability of the Active Drag Assessment Using an Isotonic Resisted Sprint Protocol in Human Swimming. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power Tower. Available online: https://www.tpiswim.com/power-tower (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Dominguez-Castells, R.; Arellano, R. Effect of Different Loads on Stroke and Coordination Parameters during Freestyle Semi-Tethered Swimming. J. Hum. Kinet. 2012, 32, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahill, M.J.; Oliver, J.L.; Cronin, J.B.; Clark, K.P.; Cross, M.R.; Lloyd, R.S. Sled-Pull Load–Velocity Profiling and Implications for Sprint Training Prescription in Young Male Athletes. Sports 2019, 7, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareja-Blanco, F.; Rodríguez-Rosell, D.; Sánchez-Medina, L.; Sanchis-Moysi, J.; Dorado, C.; Mora-Custodio, R.; Yáñez-García, J.M.; Morales-Alamo, D.; Pérez-Suárez, I.; Calbet, J.A.L.; et al. Effects of Velocity Loss during Resistance Training on Athletic Performance, Strength Gains and Muscle Adaptations. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2017, 27, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weakley, J.; Mann, B.; Banyard, H.; McLaren, S.; Scott, T.; Garcia-Ramos, A. Velocity-Based Training: From Theory to Application. Strength Cond. J. 2021, 43, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, C.B.; Sanders, R.H.; Psycharakis, S.G. Upper Limb Kinematic Differences between Breathing and Non-Breathing Conditions in Front Crawl Sprint Swimming. J. Biomech. 2015, 48, 3995–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, S.V.; Duplishcheva, O.A. Active Drag, Useful Mechanical Power Output and Hydrodynamic Force Coefficient in Different Swimming Strokes at Maximal Velocity. J. Biomech. 1992, 25, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, C. Inter-Analyst Variability in Swimming Competition Analysis. Procedia Eng. 2014, 72, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tor, E.; Pease, D.L.; Ball, K.A.; Hopkins, W.G. Monitoring the Effect of Race-Analysis Parameters on Performance in Elite Swimmers. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2014, 9, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, W. How to Interpret Changes in an Athletic Test. Sportscience 2004, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.G. A Spreadsheet for Monitoring an Individual’s Changes and Trend. Sportscience 2017, 21, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sands, W.; Cardinale, M.; McNeal, J.; Murray, S.; Sole, C.; Reed, J.; Apostolopoulos, N.; Stone, M. Recommendations for Measurement and Management of an Elite Athlete. Sports 2019, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSCA. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning; Haff, G.G., Triplett, T., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantaki, M.; Winter, E.M. The Effectiveness of a Leg-Kicking Training Program on Performance and Physiological Measures of Competitive Swimmers. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2007, 2, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, H.M.; Beek, P.J. Biomechanics of Competitive Front Crawl Swimming. Sports Med. 1992, 13, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Duncan, N.D.; Volek, J.S. Resistance Training and Elite Athletes Adaptations and Program Considerations. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1998, 28, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T.; Seiler, S.; Sandbakk, Ø.; Tønnessen, E. The Training and Development of Elite Sprint Performance: An Integration of Scientific and Best Practice Literature. Sports Med. Open 2019, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, D.J.; Owen, N.J.; Cunningham, D.J.; Cook, C.J.; Kilduff, L.P. Strength and Power Predictors of Swimming Starts in International Sprint Swimmers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thng, S.; Pearson, S.; Rathbone, E.; Keogh, J.W.L. The Prediction of Swim Start Performance Based on Squat Jump Force-Time Characteristics. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderbank, J.A.; Comfort, P.; McMahon, J.J. Association of Jumping Ability and Maximum Strength with Dive Distance in Swimmers. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2021, 16, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keiner, M.; Wirth, K.; Fuhrmann, S.; Kunz, M.; Hartmann, H.; Haff, G.G. The Influence of Upper- and Lower-Body Maximum Strength on Swim Block Start, Turn, and Overall Swim Performance in Sprint Swimming. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 2839–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; Gay, A.; Cuenca-Fernández, F.; López-Belmonte, Ó.; Morales-Ortíz, E.; López-Contreras, G.; Arellano, R. The Relationship between Tethered Swimming, Anaerobic Critical Velocity, Dry-Land Strength, and Swimming Performance. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2022, 22, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.D.; Monteiro, A.S.; Fonseca, P.; Silva, A.J.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Pyne, D.B.; Fernandes, R.J. Swimming Sprint Performance Depends on Upper/Lower Limbs Strength and Swimmers Level. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilduff, L.P.; Cunningham, D.J.; Owen, N.J.; West, D.J.; Bracken, R.M.; Cook, C.J. Effect of Postactivation Potentiation on Swimming Starts in International Sprint Swimmers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 2418–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, A.P.; Sparks, K.E.; Kullman, E.L. Postactivation Potentiation Enhances Swim Performance in Collegiate Swimmers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkhoshansky, Y.; Siff, M. Supertraining. 2009. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Supertraining-Yuri-V-Verkhoshansky/dp/8890403810 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

| Swimmer | 50 m PB (s) | V0 (m/s) | L0 (kg) | rL0 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | 22.28 | 2.06 | 31.9 | 39.0 |

| 1 | 22.10 | 2.05 | 34.6 | 38.2 |

| 2 | 21.68 | 1.91 | 34.9 | 41.6 |

| Session Focus | Warm Up | Main Set—Round 1 | Main Set—Round 2 | Main Set—Round 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Competence | 300 m choice, 8 × 50 m choice skill progression | 3 × 1 bucket swim to 15 m 2 reps technical focus 1 rep speed focus (Time Target) 3 × 20 m fast swim with fins on 80 s 200 m recovery | Repeat Round 1 with 1/2 bucket of water added 3 × 20 m fast swim with fins and paddles on 80 s | Repeat Round 2 with 1/2 bucket of water added |

| Speed-Strength | 300 m choice, 8 × 50 m choice skill progression | 3 × 2 bucket swim to 15 m 2 reps technical focus 1 rep speed focus (Time Target) 3 × 20 m fast swim with fins on 90 s 200 m recovery | Repeat Round 1 with 1 bucket of water added 3 × 20 m fast swim with fins and paddles on 90 s | Repeat Round 2 with 1 bucket of water added |

| Power | 800 m choice | 1 × 3 bucket swim to 15 m on 2 min 3 × 20 m fast swim with fins and paddles (Time Target) 1 × 25 m distance per stroke focus 175 m recovery | 3 × 3 bucket swim to 15 m on 2 min 1 × 20 m fast swim with fins and paddles (Time Target) 1 × 25 m distance per stroke focus 175 m recovery | 2 × 3 bucket swim to 15 m on 2 min 2 × 20 m fast swim with fins and paddles (Time Target) 1 × 25 m distance per stroke focus 175 m recovery |

| Variable | Pre- | Post- | % Change | TE (%) | SWC (%) | % Chance That True Change Is Decrease/Trivial/Increase | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity at 1 kg (m/s) | 1.91 | 1.98 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 2/5/93 | Very Likely Increase |

| Velocity at 5 kg (m/s) | 1.66 | 1.77 | 6.4 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 6/6/88 | Possible Increase |

| Velocity at 9 kg (m/s) | 1.34 | 1.46 | 9.2 | 3.5 | 2.0 | 4/7/89 | Possible Increase |

| V0 (m/s) | 1.99 | 2.06 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 8/7/85 | Possible Increase |

| L0 (kg) | 28.1 | 31.9 | 13.6 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 1/5/94 | Very Likely Increase |

| rL0 (%) | 33.2 | 39.0 | 17.4 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 1/1/98 | Very Likely Increase |

| Absolute Slope (m/s/kg) | −0.071 | −0.064 | 9.0 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 86/11/3 | Possible Trivial Decrease |

| Relative Slope (m/s/%) | −0.060 | −0.053 | 11.9 | 5.1 | 2.3 | 89/7/4 | Possible Decrease |

| Active Drag (N) | 119.5 | 140.5 | 17.5 | 6.1 | 3.9 | 3/7/90 | Very Likely Increase |

| Date | 16 February 2024 | 9 March 2024 | 12 April 2024 | 25 May 2024 | 21 June 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage of Intervention | Pre- | Intra- | Post- | ||

| Official Time (s) | 22.23 | 22.34 | 22.39 | 21.94 | 21.94 |

| Race Segment—Start | |||||

| 0 to 15 m (s) | 5.52 | 5.62 | 5.60 | 5.48 | 5.58 |

| Race Segment—Free Swimming | |||||

| 15 to 45 m (s) | 14.46 | 14.02 | 14.34 | 14.02 | 13.96 |

| Race Segment—Finish | |||||

| 45 to 50 m (s) | 2.25 | 2.70 | 2.45 | 2.44 | 2.40 |

| First 25 m Analysis | |||||

| Stroke Length (m) | 2.01 | 2.04 | 2.07 | 2.07 | 2.14 |

| Stroke Rate (cycles/min) | 63.8 | 62.1 | 59.6 | 62.5 | 61.2 |

| Velocity (m/s) | 2.14 | 2.11 | 2.06 | 2.16 | 2.18 |

| Second 25 m Analysis | |||||

| Stroke Length (m) | 1.93 | 2.09 | 2.00 | 1.97 | 2.04 |

| Stroke Rate (cycles/min) | 62.9 | 62.1 | 62.5 | 64.3 | 62.1 |

| Velocity (m/s) | 2.02 | 2.16 | 2.08 | 2.11 | 2.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Keating, R.; Kennedy, R.; McCabe, C. Applying Load–Velocity Profiling to Guide In-Water Resistance Training in an Olympic-Level Swimmer: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12790. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312790

Keating R, Kennedy R, McCabe C. Applying Load–Velocity Profiling to Guide In-Water Resistance Training in an Olympic-Level Swimmer: A Case Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12790. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312790

Chicago/Turabian StyleKeating, Ryan, Rodney Kennedy, and Carla McCabe. 2025. "Applying Load–Velocity Profiling to Guide In-Water Resistance Training in an Olympic-Level Swimmer: A Case Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12790. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312790

APA StyleKeating, R., Kennedy, R., & McCabe, C. (2025). Applying Load–Velocity Profiling to Guide In-Water Resistance Training in an Olympic-Level Swimmer: A Case Study. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12790. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312790