Research Advances in the Distribution, Migration, Transformation, and Removal of Antibiotics in Aquatic Ecosystems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Antibiotics in Aquatic Environment

| Antibiotic Classes | Abbreviation | Representative Drugs | Main Sources | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Lactam | penicillin (PEN), amoxicillin (AMX), ampicillin (AMP), cefuroxime, cefquinolone (CPM) | chemical pharmaceuticals, microbial fermentation | [20] | |

| Aminoglycosides | AGs | streptomycin (SM), gentamicin (GM), neomycin (NM), ampicillin, spectinomycin | microbial fermentation and semi-synthetic modification | [21] |

| Tetracyclines | TCs | tetramycin (OXY), chlortetracycline (CTE), doxycycline (DOX) (doxycycline) | natural extraction and semi-synthesis | [22,23] |

| Amphenicols | CMP | fluorfenicol, methyldisulfonate | natural extraction and chemical synthesis of microorganisms | [24] |

| Lincosamide | LCM | lincomycin (LCM), clindamycin (CLM) (CLM), clindamycin phosphate | microbial fermentation and semi-synthetic modification | [23] |

| Quinolones | QNs | nalidixic acid, pipemidic acid, norfloxacin (NOR), ciprofloxacin (CIP), ofloxacin (OFX), levofloxacin (LVX) | chemical synthesis | [25] |

| Antimicrobial Peptides | AMPs | vancomycin (VAN), nvancosin, daptomycin, polymyxin B (PB), polymyxin E (CT) | microbial fermentation | [26] |

| Sulfonamides | SAs | sulfadiazine (SD), sulfamethoxazole (SMZ, sulfamethoxazole), sulfasalazine (SASP), sulfaguanidine (SG) | chemical synthesis | [27] |

| Macrolides | MA | erythromycin (ERY), azithromycin (AZM), clarithromycin (CLR), acetylspiramycin (SPI) | microbial fermentation | [15] |

3. Distribution of Antibiotics in Global Aquatic Environment

4. Antibiotic Pollution in Aquatic Environments

4.1. Sources of Antibiotics in Aquatic Environments

4.1.1. WWTPs

4.1.2. Pharmaceutical Industry Wastewater

4.1.3. Livestock and Aquaculture Farming Industry

4.1.4. Soil Percolation and Filtration

4.2. Migration and Transformation of Antibiotics in Aquatic Environments

4.3. The Impact of Antibiotics on the Ecological Environment

4.4. Spread of Resistance Genes and Ecological Risks

4.4.1. Mechanism and Driving Factors of Resistance Gene Spread

4.4.2. Detection Strategy and Risk Assessment

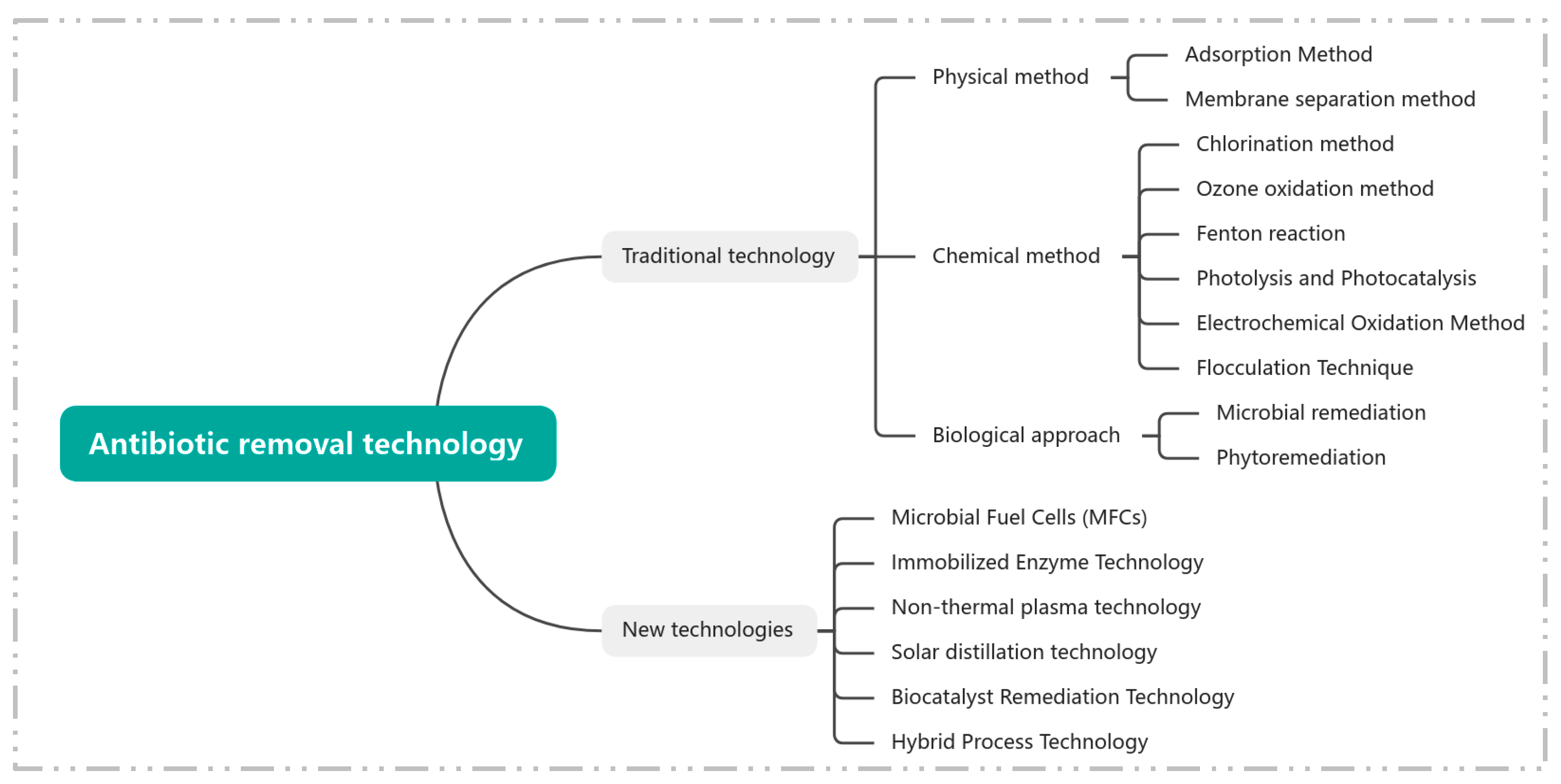

5. Artificial Removal Technologies for Antibiotics in Aquatic Environments

5.1. Factors Influencing the Efficiency of Antibiotic Removal

5.2. Traditional Antibiotic Removal Technologies

5.2.1. Physical Methods

- (1)

- Adsorption method

- (2)

- Membrane separation

5.2.2. Chemical Methods

- (1)

- Chlorination method

- (2)

- Ozone oxidation

- (3)

- Fenton reaction

- (4)

- Photolysis and photocatalysis

- (5)

- Electrochemical oxidation process

- (6)

- Flocculation process

5.2.3. Biological Methods

- (1)

- Microbial remediation

- (2)

- Phytoremediation

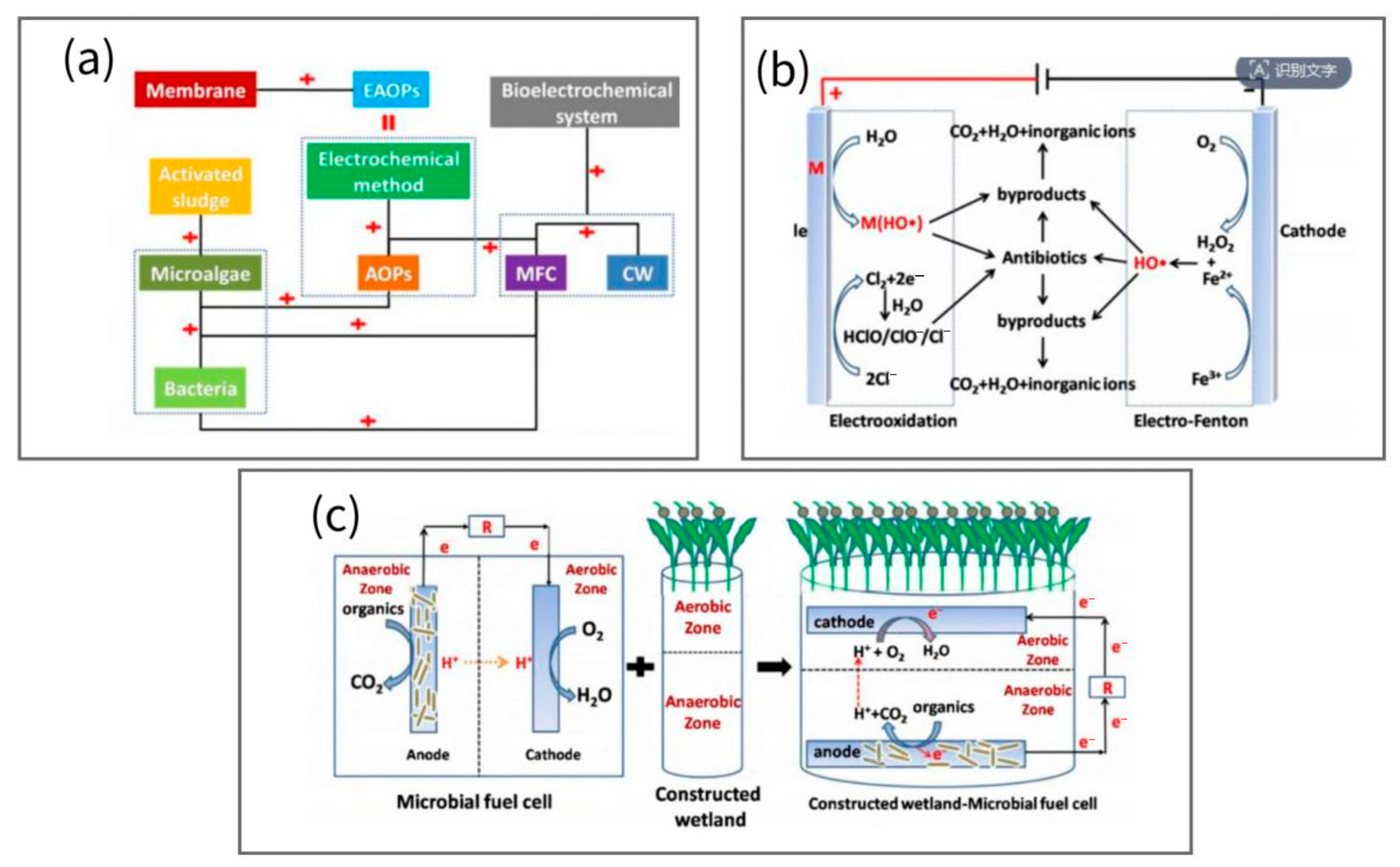

5.3. Novel Antibiotic Removal Technologies

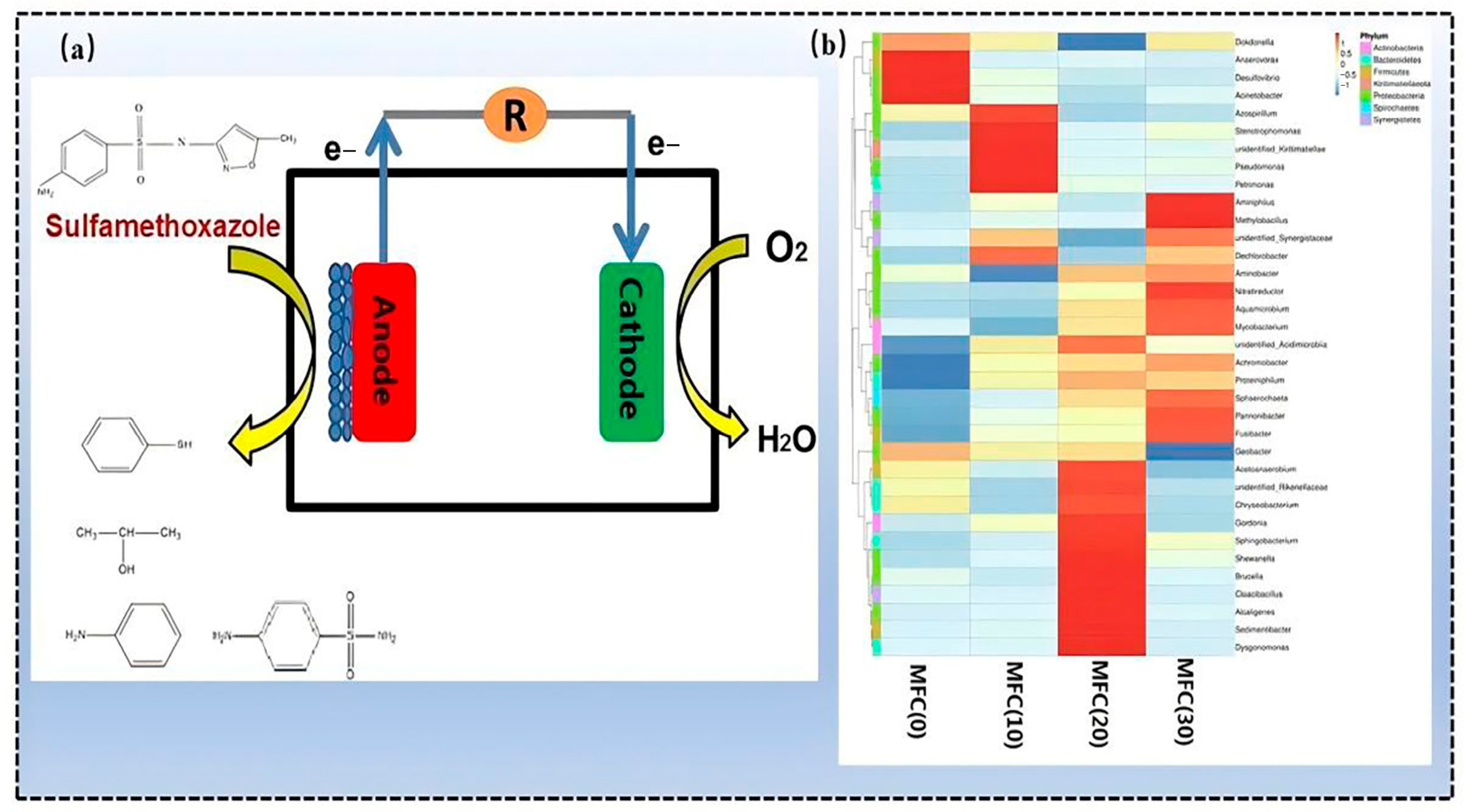

5.3.1. MFCs

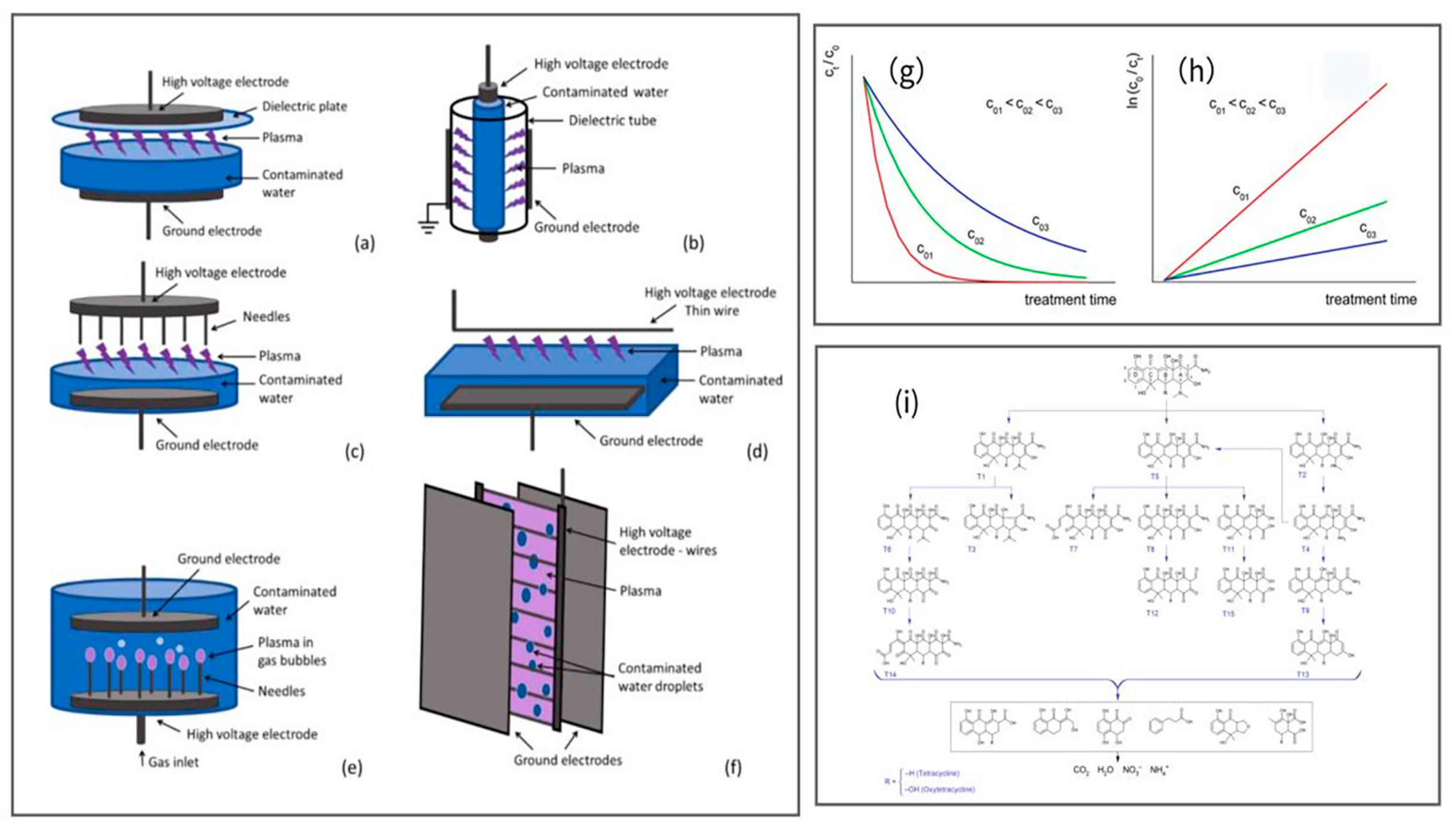

5.3.2. Non-Thermal Plasma Technique

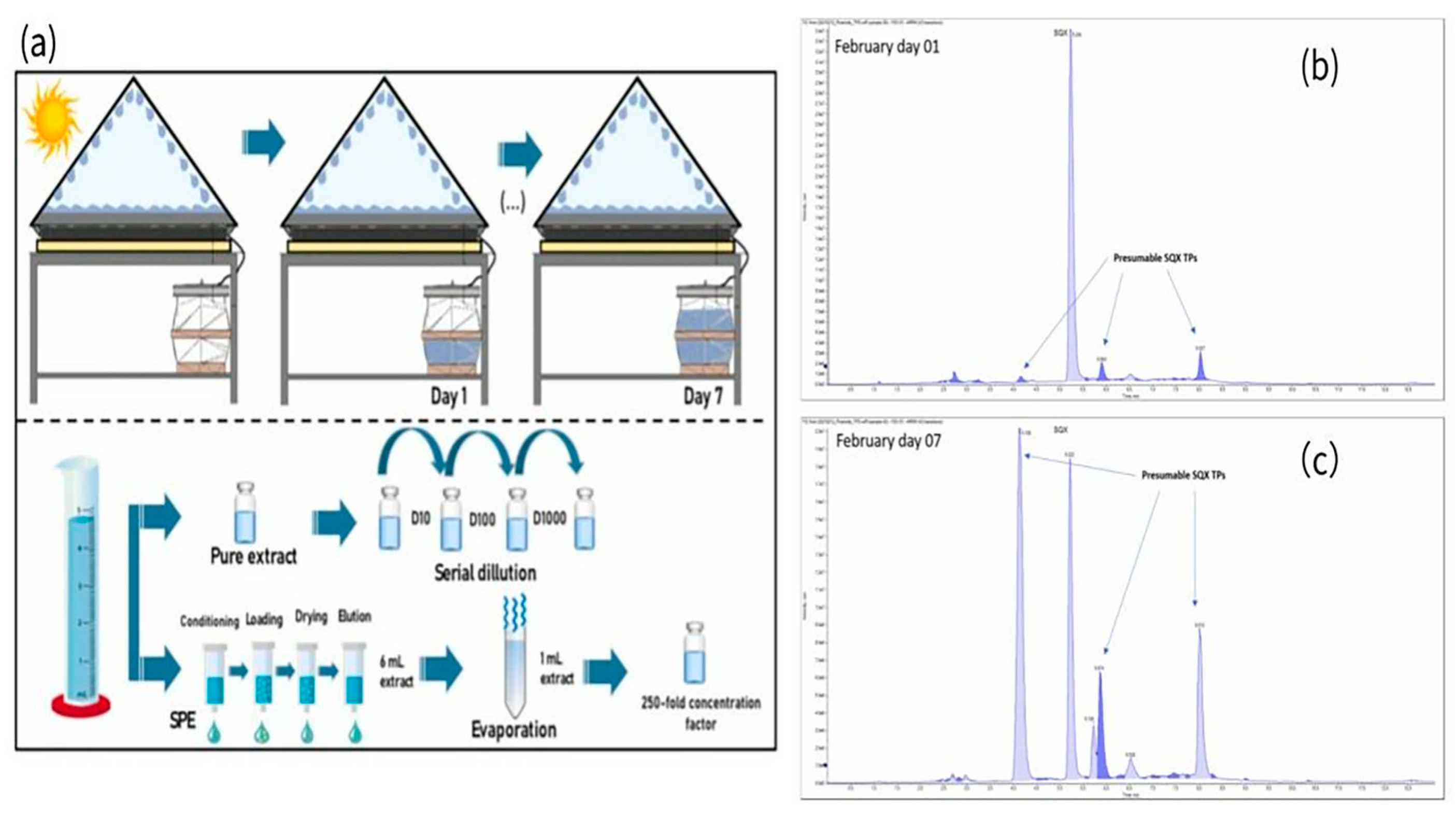

5.3.3. Solar Distillation Technology

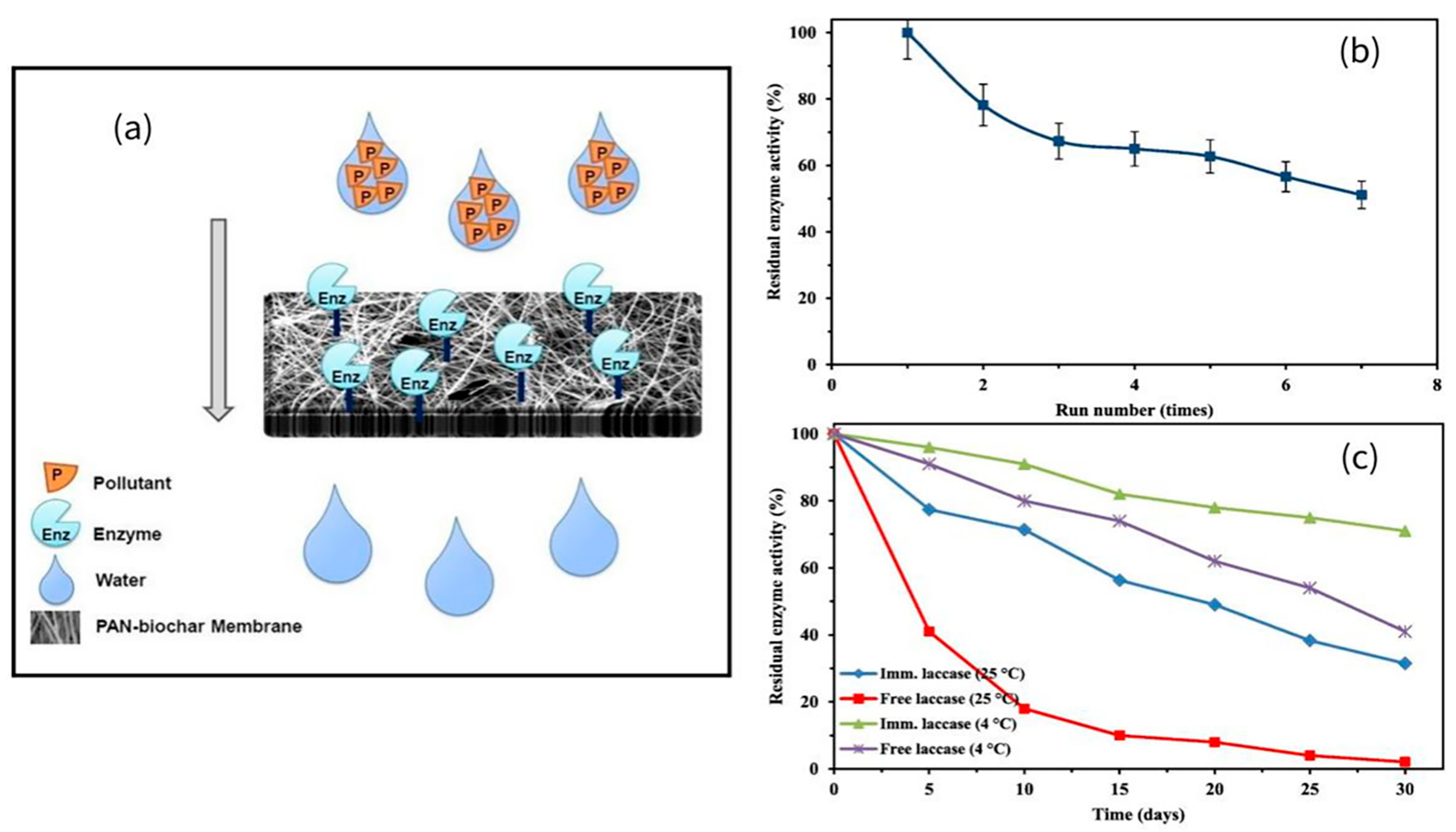

5.3.4. Biocatalyst Remediation Technology

5.3.5. Combined Process Technology

5.4. Challenges in Practical Application of Antibiotic Removal Technologies

- (1)

- Inadequate treatment efficiency and stability: Most technologies have limited degradation efficiency for recalcitrant antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones, TCs) and are strongly influenced by water quality parameters (e.g., DOM, heavy metal ions, pH).

- (2)

- Elevated byproduct and ARG risks: Chemical methods (e.g., chlorination, specific AOPs) easily generate toxic byproducts (e.g., trihalomethanes, haloaromatics), some of which are more toxic than parent antibiotics. Biological methods (e.g., activated sludge processes, microbial remediation) may promote the generation and horizontal transfer of ARGs, which spread through water bodies and pose potential threats to human health.

- (3)

- Cost and large-scale application barriers: While novel technologies (e.g., MFCs, biocatalyst remediation) have notable advantages, high initial equipment investment or raw material costs (e.g., MFC electrode materials) hinder their widespread adoption. Combined processes also involve complex operations and higher operational costs.

- (4)

- Poor adaptability to complex water bodies: In real aquatic environments, antibiotics often coexist with other pollutants (e.g., heavy metals, pesticides, endocrine disruptors). Synergistic effects of multiple pollutants may reduce removal efficiency and even create new ecological risks, increasing treatment difficulty.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paumelle, M.; Donnadieu, F.; Joly, M.; Besse-Hoggan, P.; Artigas, J. Effects of sulfonamide antibiotics on aquatic microbial community composition and functions. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Yu, W.; Mo, J.; Rehman, F.; Kasahara, T.; Guo, J. Does exposure timing of macrolide antibiotics affect the development of river periphyton? Insights into the structure and function. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 275, 107070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jampani, M.; Gothwal, R.; Mateo-Sagasta, J.; Langan, S. Water quality modelling framework for evaluating antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments. J. Hazard. Mater. Lett. 2022, 3, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, W.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Ke, Y.; Sun, W.; Ni, J. A duodecennial national synthesis of antibiotics in China's major rivers and seas (2005–2016). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danner, M.C.; Robertson, A.; Behrends, V.; Reiss, J. Antibiotic pollution in surface fresh waters: Occurrence and effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 664, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, H.; Cao, W. How far do we still need to go with antibiotics in aquatic environments? Antibiotic occurrence, chemical-free or chemical-limited strategies, key challenges, and future perspectives. Water Res. 2025, 275, 123179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, L.; Xue, H.; Yang, Z.; Meng, F. Sources, dissemination, and risk assessment of antibiotic resistance in surface waters: A review. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalugendo, E.; Kachhawaha, A.S.; Silajiya, D.; Agarwal, R. Antibiotic residues in Sabarmati River, Gujarat (India): Insight into occurrence, seasonal dynamics and risk to aquatic ecosystems. Clean. Water 2025, 4, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, A.; Rui, G.; Yaqing, L.; Ran, D.; Liu, C.; Jing, D.; Anis, M.; Liu, M.; Wang, S.; Jiang, X.; et al. A mega study of antibiotics contamination in Eastern aquatic ecosystems of China: Occurrence, interphase transfer processes, ecotoxicological risks, and source modeling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, N.; Dercon, G.; Cisneros, P.; Lopez, F.A.; Wellstein, C. Adding another dimension: Temporal development of the spatial distribution of soil and crop properties in slow-forming terrace systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 283, 106543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, P.; Giri, B.S.; Shukla, P.; Gupta, P. Recent advancement in remediation of synthetic organic antibiotics from environmental matrices: Challenges and perspective. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 319, 124161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Jia, L.; Liu, J. Distribution and Migration of β-lactam Antibiotics in Urban Sewage Treatment Plants. J. Hebei Univ. Eng. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 31, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, D.; Ternes, T.A. Analytical method for the determination of the aminoglycoside gentamicin in hospital wastewater via liquid chromatography–electrospray-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2003, 1000, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cai, T.; Zhang, S.; Hou, J.; Cheng, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Q. Contamination distribution and non-biological removal pathways of typical tetracycline antibiotics in the environment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditto, V.J.; Feola, D.J. Delivering macrolide antibiotics to heal a broken heart–And other inflammatory conditions. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 184, 114252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Du, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Pan, Y.; Xue, X.; Mu, X.; Qiu, J.; Qian, Y. Mitochondrial mechanism of florfenicol-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in zebrafish using multi-omics technology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 486, 136958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Song, Y.; Ling, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhan, X.; Xing, B. Fate of emerging antibiotics in soil-plant systems: A case on fluoroquinolones. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Bai, D.; Sun, Z.; Song, J.; Dai, L. Research Progress on bioactive peptides from animal sources: A comprehensive review. Food Chem. 2025, 490, 145006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Bou, L.; Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J.; Correa-Galeote, D. Promising bioprocesses for the efficient removal of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistance genes from urban and hospital wastewaters: Potentialities of aerobic granular systems. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 123115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, N.; Gupta, D.; Ali, A.; Kumar, Y.; Akhtar, F.; Kulanthaivel, S.; Mishra, P.; Khan, F.; Khan, A.U. Broad-Spectrum Inhibitors against Class A, B, and C Type β-Lactamases to Block the Hydrolysis against Antibiotics: Kinetics and Structural Characterization. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0045022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deja, E.N. Aminoglycoside antibiotics: Trying to find a place in this world. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 2024, 46, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z. Tetracycline antibiotics: Potential anticancer drugs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 956, 175949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, Q.T.; Munoz, G.; Duy, S.V.; Do, D.T.; Bayen, S.; Sauvé, S. Analysis of sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines, triphenylmethane dyes and other veterinary drug residues in cultured and wild seafood sold in Montreal, Canada. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 94, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Qin, J.-Y.; Ru, S.; Xiong, J.-Q. Functional characterization of a novel Chlamydomonas reinhardtii hydrolase involved in biotransformation of chloramphenicol. Water Res. 2024, 265, 122285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, F.; Shao, L.; Zheng, F.; Wang, L.; Chen, F.; Yang, L. Occurrence of quinolones in cultured fish from Shandong Province, China and their health risk assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 180, 113777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnezary, F.S.; Almutairi, M.S.; Alhifany, A.A.; Almangour, T.A. Assessing Galleria mellonella as a preliminary model for systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection: Evaluating the efficacy and impact of vancomycin and Nigella sativa oil on gut microbiota. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 101824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Tambe, G.; Shard, A. Sulfonamides as tyrosine kinase modulators—A promising class of anticancer agents. Results Chem. 2023, 5, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, R.; Bashir, S.; Nabi, D.; Arshad, M. Occurrence and quantification of prevalent antibiotics in wastewater samples from Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 764, 142596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; He, X.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.; Gong, M.; Liu, D.; Clarke, J.L.; van Eerde, A. Pollution by Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in LiveStock and Poultry Manure in China, and Countermeasures. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Sun, W.; Geng, J.; Liu, X.; Jia, D.; et al. Antibiotics in global rivers. Natl. Sci. Open 2022, 1, 20220029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuferen, L.O.; Maseko, B.; Olowoyo, J.O. Occurrence of antibiotics in wastewater from hospital and convectional wastewater treatment plants and their impact on the effluent receiving rivers: Current knowledge between 2010 and 2019. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Bueno, I.; Kim, T.; Wammer, K.H.; LaPara, T.M.; Singer, R.S.; Beaudoin, A.; Arnold, W.A. Determination of the Antibiotic and Antibiotic Resistance Footprint in Surface Water Environments of a Metropolitan Area: Effects of Anthropogenic Activities. ACS ES&T Water 2023, 3, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, R.; Ternes, T.; Haberer, K.; Kratz, K.-L. Occurrence of antibiotics in the aquatic environment. Sci. Total Environ. 1999, 225, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Li, B. Occurrence, transformation, and fate of antibiotics in municipal wastewater treatment plants. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 41, 951–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymańska, U.; Wiergowski, M.; Sołtyszewski, I.; Kuzemko, J.; Wiergowska, G.; Woźniak, M.K. Presence of antibiotics in the aquatic environment in Europe and their analytical monitoring: Recent trends and perspectives. Microchem. J. 2019, 147, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Ma, L.; Yu, Q.; Yang, J.; Su, W.; Hilal, M.G.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, H. The source, fate and prospect of antibiotic resistance genes in soil: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 976657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanusi, I.O.; Olutona, G.O.; Wawata, I.G.; Onohuean, H. Occurrence, environmental impact and fate of pharmaceuticals in groundwater and surface water: A critical review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 90595–90614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, W.; Long, M.; Zhang, R.; Pan, D.; Wei, C.; Ding, M. Temporal and spatial distribution, status and progress of treatment technologies for antibiotic-bearing groundwater. Geol. China 2025, 52, 1352–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga-Gómez, M.; Nebot, C.; Falqué, E.; Pérez, B.; Franco, C.M.; Cepeda, A. Determination of pharmaceuticals and heavy metals in groundwater for human and animal consumption and crop irrigation in Galicia. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2021, 38, 2055–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBolujoko, N.B.; Olorunnisola, D.; Poudel, S.; Omorogie, M.O.; Ogunlaja, O.O.; Olorunnisola, C.G.; Adesina, M.; Deguenon, E.; Dougnon, V.; Alfred, M.O.; et al. Occurrence profiling, risk assessment, and correlations of antimicrobials in surface water and groundwater systems in Southwest Nigeria. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2024, 26, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekizuka, T.; Itokawa, K.; Tanaka, R.; Hashino, M.; Yatsu, K.; Kuroda, M. Metagenomic Analysis of Urban Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluents in Tokyo. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 4763–4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, X.; Yin, D.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Z. Occurrence, distribution and seasonal variation of antibiotics in the Huangpu River, Shanghai, China. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.J.; de Pedro, C.; Paxeus, N. Effluent from drug manufactures contains extremely high levels of pharmaceuticals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 148, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, J.; Söderström, H.; Lindberg, R.H.; Phan, C.; Tysklind, M.; Larsson, D.G.J. Contamination of surface, ground, and drinking water from pharmaceutical production. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2009, 28, 2522–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Vellanki, B.P. Occurrence of emerging contaminants in highly anthropogenically influenced river Yamuna in India. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 146741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, P.; Zang, Y.; Liu, X. Antibiotics in aquatic environments of China: A review and meta-analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 199, 110668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-L.; Wang, X.-M.; Wang, W.-H.; Hu, X.-Y.; Gao, L.-W.; Sun, X.-B. Distribution and Ecological Risk Assessment of Antibiotics in the Songhua River Basin of the Harbin Section and Ashe River. Huan Jing Ke Xue 2021, 42, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Xing, L.; Yu, M.; Deng, X. Review on the pollution situation and behavior of antibiotics in the karst groundwater system. Ground Water 2021, 43, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jin, K.; Wu, L. The status of antibiotic contamination in multiple media of China. Appl. Chem. Eng. 2024, 53, 1635–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Shao, M.; Liang, M.; Tang, J.; Wang, R. Occurrence and distribution of antibiotics in the surface water of a typical urban river in the Yangtze River Delta. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2018, 37, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Wang, N.; Guo, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Lei, L.; Luo, Y. Antibiotic and Resistance Gene Presence and Risk in Watersheds of China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, B.; Liang, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, L. Occurrence, spatial distribution, source apportionment, and risk assessment of antibiotics in Yangtze river surface water. Emerg. Contam. 2025, 11, 100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajulo, S.; Awosile, B. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS 2022): Investigating the relationship between antimicrobial resistance and antimicrobial consumption data across the participating countries. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A.J.; Chipeta, M.G.; Haines-Woodhouse, G.; Kumaran, E.P.A.; Hamadani, B.H.K.; Zaraa, S.; Henry, N.J.; Deshpande, A.; Reiner, R.C.; Day, N.P.J.; et al. Global antibiotic consumption and usage in humans, 2000–18: A spatial modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e893–e904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Rodas-Zuluaga, L.I.; López-Pacheco, I.Y.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Aghalari, Z.; Limón, D.S.; Iqbal, H.M.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Sources of antibiotics pollutants in the aquatic environment under SARS-CoV-2 pandemic situation. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Galan, M.J.; Diaz-Cruz, M.S.; Barcelo, D. Occurrence of sulfonamide residues along the Ebro river basinRemoval in wastewater treatment plants and environmental impact assessment. Environ. Int. 2011, 37, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Zambello, E. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in urban wastewater: Removal, mass load and environmental risk after a secondary treatment—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Yan, L.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Chen, S. MOF-derived DGT for selective monitoring of quinolones and tetracyclines: Tracking antibiotics risks in urban wastewater treatment plant. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lu, Y.; Song, S.; Yang, S.; Wu, Y.; Cui, H. Industrial source discharge estimation for pharmaceutical and personal care products in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 381, 135129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, J.; Qu, Q.; Lu, T.; Du, B.; Ke, M.; Zhang, M.; Qian, H. Changes in bacterial community structure and antibiotic resistance genes in soil in the vicinity of a pharmaceutical factory. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 158, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayan, R.A. Pharmaceutical effluent evokes superbugs in the environment: A call to action. Biosaf. Health 2023, 5, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielen, A.; Šimatović, A.; Kosić-Vukšić, J.; Senta, I.; Ahel, M.; Babić, S.; Jurina, T.; Plaza, J.J.G.; Milaković, M.; Udiković-Kolić, N. Negative environmental impacts of antibiotic-contaminated effluents from pharmaceutical industries. Water Res. 2017, 126, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shi, W.; Li, H.; Xu, N.; Zhang, R.; Chen, X.; Sun, W.; Wen, D.; He, S.; Pan, J.; et al. Antibiotics in water and sediments of rivers and coastal area of Zhuhai City, Pearl River estuary, south China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-Q.; Ying, G.-G.; Pan, C.-G.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zhao, J.-L. Comprehensive Evaluation of Antibiotics Emission and Fate in the River Basins of China: Source Analysis, Multimedia Modeling, and Linkage to Bacterial Resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 6772–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepi, M.; Focardi, S. Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in Aquaculture and Climate Change: A Challenge for Health in the Mediterranean Area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luby, E.M.; Moorman, T.B.; Soupir, M.L. Fate and transport of tylosin-resistant bacteria and macrolide resistance genes in artificially drained agricultural fields receiving swine manure. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 1126–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiang, L.; Mo, C.H.; Li, Y.; Cai, Q.; Huang, X.; Wu, X.; Li, H. Migration behavior of quinolone antibiotics in soil and its influencing factors. J. Agro-Environ. Sci. 2014, 33, 1345–1350. Available online: https://www.aed.org.cn/nyhjkxxben/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=2014-7013 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kodešová, R.; Grabic, R.; Kočárek, M.; Klement, A.; Golovko, O.; Fér, M.; Nikodem, A.; Jakšík, O. Pharmaceuticals’ sorptions relative to properties of thirteen different soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 511, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gothwal, R.; Shashidhar, T. Antibiotic Pollution in the Environment: A Review. CLEAN–Soil Air Water 2015, 43, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, L.; Santás-Miguel, V.; Cela-Dablanca, R.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E.; Rodríguez-Seijo, A.; Arias-Estévez, M. Clarithromycin as soil and environmental pollutant: Adsorption-desorption processes and influence of pH. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, R.; Ke, D.; Suo, H.; Wang, S.; Ma, E.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C. Intraparticle sorption and desorption of antibiotics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Sui, M.; Qin, C.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhao, J. Migration, transformation and removal of macrolide antibiotics in the environment: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 26045–26062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Junaid, M.; Chen, G.; Wang, J. Interactions and associated resistance development mechanisms between microplastics, antibiotics and heavy metals in the aquaculture environment. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 1028–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, C.; Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Kristiansson, E.; Larsson, D.G.J. Co-occurrence of resistance genes to antibiotics, biocides and metals reveals novel insights into their co-selection potential. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doretto, K.M.; Rath, S. Sorption of sulfadiazine on Brazilian soils. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Xie, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Xie, C.; Wang, Z. Adsorption behavior of three fluoroquinolone antibiotics on sediments of the Yellow River. J. Lanzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2016, 52, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, B.; Yao, Z.W. Research progress on the occurrence and environmental behavior of antibiotics in the marine environment. Environ. Chem. 2023, 42, 779–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, I.; He, H.; Kinsley, A.C.; Ziemann, S.J.; Degn, L.R.; Nault, A.J.; Beaudoin, A.L.; Singer, R.S.; Wammer, K.H.; Arnold, W.A. Biodegradation, photolysis, and sorption of antibiotics in aquatic environments: A scoping review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 897, 165301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timm, A.; Borowska, E.; Majewsky, M.; Merel, S.; Zwiener, C.; Bräse, S.; Horn, H. Photolysis of four β-lactam antibiotics under simulated environmental conditions: Degradation, transformation products and antibacterial activity. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651 Pt 1, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Lv, K.; Deng, C.; Yu, Z.; Shi, J.; Johnson, A.C. Persistence and migration of tetracycline, sulfonamide, fluoroquinolone, and macrolide antibiotics in streams using a simulated hydrodynamic system. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1532–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Liu, L.M.; Zou, S.C. Photodegradation of erythromycin and roxithromycin antibiotics in aquatic environment. Guangzhou Chem. 2008, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Cai, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C. Photodegradation of fluoroquinolone antibiotic gatifloxacin in aqueous solutions. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.M.; Ullman, J.L.; Teel, A.L.; Watts, R.J. pH and temperature effects on the hydrolysis of three β-lactam antibiotics: Ampicillin, cefalotin and cefoxitin. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 466, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Kück, U. Cephalosporins as key lead generation beta-lactam antibiotics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 8007–8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftin, K.A.; Adams, C.D.; Meyer, M.T.; Surampalli, R. Effects of Ionic Strength, Temperature, and pH on Degradation of Selected Antibiotics. J. Environ. Qual. 2008, 37, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ke, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, M.; Chen, C.; Xie, S. Enrichment of tetracycline-degrading bacterial consortia: Microbial community succession and degradation characteristics and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 448, 130984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čvančarová, M.; Moeder, M.; Filipová, A.; Cajthaml, T. Biotransformation of fluoroquinolone antibiotics by ligninolytic fungi–metabolites, enzymes and residual antibacterial activity. Chemosphere 2015, 136, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Q.; Sun, W.; Zhang, G.D.; Cao, L.; Gu, W.; Xiao, W.; Yu, Q. Isolation, screening, and efficacy evaluation of bacterial strains for typical antibiotic wastewater purification. J. China Agric. Univ. 2008, 13, 97–101. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTExNzE2MDExNxIRemdueWR4eGIyMDA4MDQwMTgaCHRiMWt5a3Fm (accessed on 1 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.-J.; Han, P.; Yu, Y.; Wang, B.; Men, Y.; Wagner, M.; Wu, Q.L. Cometabolic biotransformation and microbial-mediated abiotic transformation of sulfonamides by three ammonia oxidizers. Water Res. 2019, 159, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, X.; Xie, J. Effects of antibiotics stress on root development, seedling growth, antioxidant status and abscisic acid level in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 252, 114621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Ying, T.; Ying, Z. Characteristics of removal of waste-water marking pharmaceuticals with typical hydrophytes in the urban rivers. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.B.; Jiang, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, Z. Toxic effects of sulfamethoxazole on zebrafish embryos/larvae. Environ. Pollut. Control 2020, 42, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhang, C.-M.; Jiang, H.-Y. Lipid-lowering drug clofibric acid promotes conjugative transfer of RP4 plasmid carrying antibiotic resistance genes by multiple mechanisms. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben, Y.; Fu, C.; Hu, M.; Liu, L.; Wong, M.H.; Zheng, C. Human health risk assessment of antibiotic resistance associated with antibiotic residues in the environment: A review. Environ. Res. 2019, 169, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Yan, Y.; Pu, Y.; Lin, S.; Qiu, J.-G.; Jiang, B.-H.; Keller, M.I.; Wang, M.; Bork, P.; Chen, W.-H.; et al. Enterotypes of the human gut mycobiome. Microbiome 2023, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarean, M.; Dave, S.H.; Brar, S.K.; Kwong, R.W.M. Environmental drivers of antibiotic resistance: Synergistic effects of climate change, co-pollutants, and microplastics. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chang, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, T. Environmentally relevant concentrations of representative aquatic compounds promote the conjugative transfer of antibiotic resistance genes. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 79, 108936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, B.; Wang, T.; Li, J.; Qi, J.; Luo, J.; Zhang, T.; Xu, X.; Hou, L. A review of antibiotic resistance genes in major river basins in China: Distribution, drivers, and risk. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 371, 125920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Guo, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Deng, L.; Yang, H.; He, T.; Wu, P.; Zhang, Y. Distribution and driving mechanisms of antibiotic resistance genes in urbanized watersheds. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Chen, S.-Y.; Zhang, J.-X.; He, X.-X.; Xiong, W.-G.; Sun, Y.-X. Variations of antibiotic resistance profiles in chickens during administration of amoxicillin, chlortetracycline and florfenicol. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panja, S.; Sarkar, D.; Datta, R. Removal of tetracycline and ciprofloxacin from wastewater by vetiver grass (Chrysopogon zizanioides (L.) Roberty) as a function of nutrient concentrations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 34951–34965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homem, V.; Santos, L. Degradation and removal methods of antibiotics from aqueous matrices—A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2304–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W. Adsorptive removal of antibiotics from water and wastewater: Progress and challenges. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 532, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Tang, A.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y. Microbial community evolution and fate of antibiotic resistance genes along six different full-scale municipal wastewater treatment processes. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 272, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimabuku, K.K.; Kearns, J.P.; Martinez, J.E.; Mahoney, R.B.; Moreno-Vasquez, L.; Summers, R.S. Biochar sorbents for sulfamethoxazole removal from surface water, stormwater, and wastewater effluent. Water Res. 2016, 96, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.-P.; Liu, X.; Niu, Z.-S.; Lu, D.-P.; Zhao, S.; Sun, X.-L.; Wu, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-R.; Tou, F.-Y.; Hou, L.; et al. Seasonal and spatial distribution of antibiotic resistance genes in the sediments along the Yangtze Estuary, China. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 242, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, T.; He, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, T.; Zhu, L. Efficient degradation of antibiotics by non-thermal discharge plasma: Highlight the impacts of molecular structures and degradation pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395, 125091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Pu, M.; Xie, X. Combined coagulation and membrane treatment for anaerobically digested manure centrate: Contaminant residuals and membrane fouling. Environ. Res. 2023, 218, 115010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangi, A.K.; Sharma, B.; Hill, R.T.; Shukla, P. Bioremediation through microbes: Systems biology and metabolic engineering approach. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2019, 39, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Díaz, J.; Sánchez-Polo, M.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Canonica, S.; von Gunten, U. Advanced oxidation of the surfactant SDBS by means of hydroxyl and sulphate radicals. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 163, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.Z.; Sun, X.-F.; Liu, J.; Song, C.; Wang, S.-G.; Javed, A. Enhancement of ciprofloxacin sorption on chitosan/biochar hydrogel beads. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Chen, H.; Reinhard, M.; Mao, F.; Gin, K.Y.-H. Occurrence and removal of multiple classes of antibiotics and antimicrobial agents in biological wastewater treatment processes. Water Res. 2016, 104, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Quan, X.; Huang, X.; Cheng, C.; Yang, L.; Cheng, Z. Enhancement of micro-filtration performance for biologically-treated leachate from municipal solid waste by ozonation in a micro bubble reactor. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 207, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, J.L.; Benitez, F.J.; Leal, A.I.; Real, F.J.; Teva, F. Membrane filtration technologies applied to municipal secondary effluents for potential reuse. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P.; Kulkarni, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Chakrapani, H. Visible-Light Controlled Release of a Fluoroquinolone Antibiotic for Antimicrobial Photopharmacology. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 2155–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Galvis, E.A.; Giraldo-Aguirre, A.L.; Silva-Agredo, J.; Flórez-Acosta, O.A.; Torres-Palma, R.A. Removal of antibiotic cloxacillin by means of electrochemical oxidation, TiO2 photocatalysis, and photo-Fenton processes: Analysis of degradation pathways and effect of the water matrix on the elimination of antimicrobial activity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 6339–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, Q.; Lei, X.; Gong, S. Fabrication of Ag/AgBr/Ag3VO4 composites with high visible light photocatalytic performance. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 5100–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, X.; Liu, B.; Huang, T.; Liu, R.; Liu, X. Metagenome sequencing reveals shifts in phage-associated antibiotic resistance genes from influent to effluent in wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 2024, 253, 121289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.E.; Dolan, M.E.; Bottomley, P.J.; Semprini, L. Utilization of Fluoroethene as a Surrogate for Aerobic Vinyl Chloride Transformation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 6378–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Shen, Y. Degradation of antibiotics and inactivation of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in Cephalosporin C fermentation residues using ionizing radiation, ozonation and thermal treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 382, 121058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, C.; Han, W.; Gu, P.; Jing, R.; Yang, Q. Antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors in the plastisphere in wastewater treatment plant effluent: Health risk quantification and driving mechanism interpretation. Water Res. 2025, 271, 122896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.H.; Zhang, G.; Wai, O.W.H.; Zou, S.C.; Li, X.D. Transport and adsorption of antibiotics by marine sediments in a dynamic environment. J. Soils Sediments 2009, 9, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Pu, C.; Yu, X.; Sun, Y.; Chen, J. Removal of tetracyclines, sulfonamides, and quinolones by industrial-scale composting and anaerobic digestion processes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 35835–35844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Garg, A. Degradation of ciprofloxacin using Fenton's oxidation: Effect of operating parameters, identification of oxidized by-products and toxicity assessment. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, B.; Singh, A.K.; Kim, H.; Lichtfouse, E.; Sharma, V.K. Treatment of organic pollutants by homogeneous and heterogeneous Fenton reaction processes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofrano, G.; Pedrazzani, R.; Libralato, G.; Carotenuto, M. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Antibiotics Removal: A Review. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 1054–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.; Li, X.; Xia, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, Z. Adsorptive and photocatalytic removal of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in water by metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 337, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.K.; Saha, A.K.; Sinha, A. Removal of ciprofloxacin using modified advanced oxidation processes: Kinetics, pathways and process optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siri, Y.; Sresung, M.; Paisantham, P.; Mongkolsuk, S.; Sirikanchana, K.; Honda, R.; Precha, N.; Makkaew, P. Antibiotic resistance genes and crAssphage in hospital wastewater and a canal receiving the treatment effluent. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 361, 124771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiańska, A.; Białk-Bielińska, A.; Stepnowski, P.; Stolte, S.; Siedlecka, E.M. Electrochemical degradation of sulfonamides at BDD electrode: Kinetics, reaction pathway and eco-toxicity evaluation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 280, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Dai, Q. Electrochemical degradation of antibiotic levofloxacin by PbO2 electrode: Kinetics, energy demands and reaction pathways. Chemosphere 2018, 205, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Xiao, Y.; Yan, W.; Ding, R.; Wang, S.; Zhao, F. The effect of bioelectrochemical systems on antibiotics removal and antibiotic resistance genes: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Sharma, V.K.; Li, H. Environmental Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance: From Problems to Solutions. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2019, 13, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ji, M.; Zhai, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in WWTP effluent-receiving water bodies and reclaimed wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrino, D.A.; Mucha, A.P.; Almeida, C.M.R.; Gao, W.; Jia, Z.; Carvalho, M.F. Biodegradation of the veterinary antibiotics enrofloxacin and ceftiofur and associated microbial community dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 581–582, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasfi, R.; Chiron, S.; Montemurro, N.; Perez, S.; Brienza, M. Biodegradation of fluoroquinolone antibiotics and the climbazole fungicide by Trichoderma species. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 23331–23341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.T.T.; Tu, L.T.C.; Le, N.P.; Dao, Q.P. A Preliminary Study on the Phytoremediation of Antibiotic Contaminated Sediment. Int. J. Phytoremediation 2013, 15, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Jaén-Gil, A.; Karavaeva, A.; Gomiero, A.; Ásmundsdóttir, Á.M.; Silva, M.J.; Salmivirta, E.; Tran, T.T.; Sarekoski, A.; Cook, J.; et al. Antibiotic resistance genes, antibiotic residues, and microplastics in influent and effluent wastewater from treatment plants in Norway, Iceland, and Finland. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; You, S.; Zhang, J.; Qi, W.; Su, R.; He, Z. An effective in-situ method for laccase immobilization: Excellent activity, effective antibiotic removal rate and low potential ecological risk for degradation products. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 308, 123271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Li, F.; Zhou, Q. Degradation mechanisms of sulfamethoxazole and its induction of bacterial community changes and antibiotic resistance genes in a microbial fuel cell. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 289, 121632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, Y. Occurrence and fate of antibiotic residues and antibiotic resistance genes in a reservoir with ecological purification facilities for drinking water sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catal, T.; Yavaser, S.; Enisoglu-Atalay, V.; Bermek, H.; Ozilhan, S. Monitoring of neomycin sulfate antibiotic in microbial fuel cells. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 268, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magureanu, M.; Bilea, F.; Bradu, C.; Hong, D. A review on non-thermal plasma treatment of water contaminated with antibiotics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 125481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, B.; Shi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Identification of antibiotic resistance genes and associated mobile genetic elements in permafrost. Sci. China Life Sci. 2021, 64, 2210–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Jiang, N.; Wang, H.; Lu, N.; Shang, K.; Li, J.; Wu, Y. Pulsed discharge plasma assisted with graphene-WO3 nanocomposites for synergistic degradation of antibiotic enrofloxacin in water. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, T. Removal of antibiotic resistance genes and pathogenicity in effluent from municipal wastewater treatment plant by plasma oxidation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, R.; Vogelmann, E.S.; de Melo, A.P.Z.; Deolindo, C.T.P.; Medeiros, B.M.d.S.; Daguer, H. Reacqua: A low-cost solar still system for the removal of antibiotics from contaminated effluents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, V.; Bansal, A.; Jha, M.K. Investigation of activated sludge characteristics and their influence on simultaneous sludge minimization and nitrogen removal from an advanced biological treatment for tannery wastewater. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 24, 102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheran, M.; Naghdi, M.; Brar, S.K.; Knystautas, E.; Verma, M.; Surampalli, R.Y. Degradation of chlortetracycline using immobilized laccase on Polyacrylonitrile-biochar composite nanofibrous membrane. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.J.; Fan, X.J.; Chen, X.P.; Ge, Z.Q. Immobilized β-lactamase on Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles for degradation of β-lactam antibiotics in wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 2203–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Wen, H.; Li, C. Occurrence, fate and health risk assessment of 10 common antibiotics in two drinking water plants with different treatment processes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 674, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, A.M.; Gómez, G.; González-Rocha, G.; Piña, B.; Vidal, G. Performance of full-scale rural wastewater treatment plants in the reduction of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes from small-city effluents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Geng, Q.; Chen, G.; Ding, Y.; Yang, F. Current Progress in Natural Degradation and Enhanced Removal Techniques of Antibiotics in the Environment: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czekalski, N.; Imminger, S.; Salhi, E.; Veljkovic, M.; Kleffel, K.; Drissner, D.; Hammes, F.; Bürgmann, H.; von Gunten, U. Inactivation of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria and Resistance Genes by Ozone: From Laboratory Experiments to Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11862–11871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Country/Region | Memory Storage Medium | Detection Concentration (ng/L) | Sampling Time | Detection Method | Limit of Detection (LOD) (ng/L) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed countries | Barcelona, Spain | Groundwater | Up to 2980 (cephalosporins, SAs, fluoroquinolones) | 2022 | LC-MS | <1 | [38] |

| Germany | Groundwater | 1173 (SAs, TCs) | 2020 | HPLC-MS | <0.5 | [39] | |

| River Tyne, northern England, UK | river | 42,370 (7 antibiotics detected) | 2021 | GC-MS | <2 | [40] | |

| Rivers in South Wales, UK | river | (SAs, fluoroquinolones; trimethoprim frequently detected) | - | - | - | [40] | |

| Parts of California, USA | Groundwater | 500–1500 (TCs) | 2019 | ELISA | <5 | [41] | |

| Tokyo Bay, Japan | Surface water | 10–50 (SAs, fluoroquinolones) | 2021 | LC-MS/MS | <0.1 | [41] | |

| Developing Countries | Southeastern & southern African countries | Surface water | (SMX): median 286, max 3,320,000; (TMP): median 122 | 2018–2022 | LC-MS | 1–5 | [30] |

| Yamuna Basin, India | river | CIP: 286 (global upper limit for rivers) | 2020 | HPLC | <0.5 | [45] | |

| Ganges Basin & coastal waters, India | Surface water, coastal water | (fluoroquinolones, SAs, MA) | - | - | - | [30] | |

| Mexico Valley Basin & Pacific coastal agricultural areas | Surface water (basin, agricultural area | >50 at some sites (SAs; detection rate 100%) | 2021 | GC-MS | <2 | [30] | |

| Northeast China (Harbin section of Songhua River) | Surface water | (SAs; minor LCM) | 2019 | LC-MS/MS | =1 | [47] | |

| North China | Aquatic environment | (fluoroquinolones) | 2010–2020 | LC-MS/MS | =0.5 | [30] | |

| Southwest China (karst areas) | Groundwater, Aquatic environment | (fluoroquinolones, TCs; high NOR detection rate in karst groundwater) | 2018–2021 | LC-MS/MS | =0.5 | [38,48] | |

| Bohai Bay of China | Aquatic environment | (SAs, MA) | 2020 | LC-MS/MS | =0.2 | [49] | |

| Lujiang Basin, Ningbo, Yangtze River Delta of China | Aquatic environment | (TCs, chloramphenicols) | 2016–2017 | LC-MS/MS | =1 | [50] | |

| Haihe Basin of China | Aquatic environment | (large concentration variation; concentrated in urban industrial zones) | 2020–2023 | LC-MS/MS | =0.5 | [51] | |

| Yangtze River Basin of China | Aquatic environment | (fluoroquinolones, MA) | 2022–2024 | LC-MS/MS | =0.1 | [52] |

| Characteristics | Parent Compounds | Transformation Products | Key Conclusion on Differences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persistence | Short half-life | Some products exhibit significantly increased persistence; for example, the half-life of photodegradation products of ciprofloxacin (CIP) (e.g., erythromycinone analogs) extends to 5–7 days, and devinylated products of norfloxacin (NOR) are more prone to accumulate in sediments | Due to their more stable structures (e.g., quinoline carboxylic acid derivatives formed after piperazine ring opening), transformation products generally have higher persistence than parent compounds, increasing the risk of environmental residues |

| Bioaccumulation | No significant bioaccumulation | Most products retain antibacterial activity: e.g., CIP-derived desethylene-N-ciprofloxacin inhibits Bacillus subtilis at 60–80% of the parent’s efficiency; a few have reduced activity but other risks (e.g., N-nitrosonorfloxacin’s antibacterial activity decreases by 30–50% but is potentially carcinogenic); only Irpex lacteus can fully eliminate OF- and NOR-derived product activity. | The bioaccumulation of products exhibits a “partially enhanced” trend, and attention should be paid to the food chain transfer risk of products with increased hydrophobicity |

| Antimicrobial Resistance Selection Pressure | Strong; can significantly inhibit the growth of Gram-positive/negative bacteria (e.g., the inhibition rate of 30 μg/mL ciprofloxacin (CIP) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa exceeds 20%) | Most products retain antibacterial activity: e.g., CIP-derived desethylene-N-ciprofloxacin inhibits Bacillus subtilis at 60–80% of the parent’s efficiency; a few have reduced activity but other risks (e.g., N-nitrosonorfloxacin’s antibacterial activity decreases by 30–50% but is potentially carcinogenic); only Irpex lacteus can fully eliminate OF- and NOR-derived product activity. | Fungal degradation cannot completely eliminate antimicrobial resistance selection pressure; most products remain “weak selection pressure sources,” and only specific fungi (e.g., Irpex lacteus) can block this risk, requiring targeted selection of degrading microorganisms |

| Technical Category | Removal Efficiency (ng–μg/L) | Key Advantages | Main Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption method | medium | low cost, simple operation, no secondary pollution | The adsorbent regeneration would cause secondary pollution and decrease the efficiency | [102,103,105,110,112] |

| Membrane separation | high | high separation efficiency and continuous operation | High cost of use; membrane pollution will cause environmental pollution | [102,108,113] |

| Chlorination method | high (for specific types) | technology mature, low cost, fast response | It produces carcinogenic disinfection byproducts; has limited effect on stable structure antibiotics; and its efficiency is affected by pH | [114,117] |

| Ozone oxidation | high | strong oxidation ability, fast reaction, no chemical residue | High energy consumption, low gas–liquid mass transfer efficiency, and potential toxic by-products | [117,119,120] |

| Fenton reaction | high | effective against hard-to-degrade antibiotics | It needs an acidic environment; produces iron-containing sludge; H2O2 is unstable | [122,125] |

| photocatalysis | medium | risks of secondary pollution are low with solar energy | dependent on light conditions; may produce toxic intermediates | [126,127,128] |

| electrochemical oxidation | high | high controllability, no chemicals added | high cost of electrodes; electrodes are easily contaminated; Low conductivity water requires electrolyte addition | [130,132] |

| flocculation | low to medium | simple to operate and low cost | the yield of sludge is high; it is sensitive to pH; it has poor effect on hydrophilic antibiotics | [106,125,133] |

| microbial remediation | low to medium | low cost, environmentally friendly | slow reaction kinetics; environmental sensitivity; may promote proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes | [100,109,135,136] |

| phytoremediation | low to medium | low cost and environmental beautification | very slow; climate-dependent; antibiotics may accumulate in the food chain | [101,109,137] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, R.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Ge, Y.; Xia, M.; Gao, X.; Ma, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; et al. Research Advances in the Distribution, Migration, Transformation, and Removal of Antibiotics in Aquatic Ecosystems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12777. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312777

Lv R, Li S, Wang X, Jia Y, Ge Y, Xia M, Gao X, Ma J, Liu B, Zhang L, et al. Research Advances in the Distribution, Migration, Transformation, and Removal of Antibiotics in Aquatic Ecosystems. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12777. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312777

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Rensheng, Sheng Li, Xiao Wang, Yinggang Jia, Yanyan Ge, Man Xia, Xing Gao, Jiahao Ma, Bengang Liu, Lingyun Zhang, and et al. 2025. "Research Advances in the Distribution, Migration, Transformation, and Removal of Antibiotics in Aquatic Ecosystems" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12777. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312777

APA StyleLv, R., Li, S., Wang, X., Jia, Y., Ge, Y., Xia, M., Gao, X., Ma, J., Liu, B., Zhang, L., Qi, T., Meng, J., Zhao, B., Jie, F., & Chen, F. (2025). Research Advances in the Distribution, Migration, Transformation, and Removal of Antibiotics in Aquatic Ecosystems. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12777. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312777