1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted traditional education worldwide. Online learning has experienced unprecedented growth, with students increasingly relying on platforms such as MOOCs [

1], Coursera, and Khan Academy to continue their studies. These platforms generate massive amounts of student interaction data daily, including exercise attempts, quiz results, and other learning activities. Although these data reflect students’ learning behaviors, their underlying knowledge states remain unobservable, making it challenging to provide personalized learning strategies for students with different learning states [

2]. Knowledge tracing [

3,

4] addresses this challenge by predicting students’ future performance on new exercises based on their past responses, thereby indirectly estimating their mastery of different knowledge concepts. By accurately capturing these latent knowledge states, educational systems can adapt learning paths, recommend targeted resources, and provide data-driven support for personalized learning and intelligent tutoring interventions [

5,

6,

7].

Existing approaches can be broadly divided into traditional methods and deep learning–based methods. Traditional methods, such as Bayesian knowledge tracing [

7], model student knowledge with simplified states, limiting their ability to capture complex learning behaviors. With the advancement of deep learning, sequence-based models use recurrent architectures to capture sequential dynamics in students’ knowledge [

8,

9,

10]. These studies continue to serve as foundational frameworks in knowledge tracing, providing a baseline for dynamically modeling knowledge evolution. Memory-augmented models enhance knowledge representations with key–value structures for finer-grained mastery tracking [

11,

12,

13]. This design explicitly maintains concept-level knowledge states, which enables dynamic updates of concept representations after each student interaction. Therefore, complex relationships between concepts can be further modeled. Attention-based approaches, inspired by the transformer architecture, capture relationships among questions and their relevance to student knowledge [

14,

15]. Graph-based methods leverage structural information via graph neural networks to model dependencies among concepts and questions [

16,

17,

18,

19]. This provides a structured view of students’ knowledge evolution. Inspired by these ideas, DyGAS integrates graph-based modeling with dynamic and static knowledge representations to achieve more robust and fine-grained knowledge tracing. Compared to traditional methods, these methods can capture more complex interaction patterns and knowledge structures.

Despite these advances, existing methods still face challenges in accurately modeling students’ knowledge states. The evolution of a student’s knowledge state depends both on their historical learning trajectory and on the latent relationships among knowledge concepts. The former reflects the accumulation and forgetting of knowledge, while the latter captures dependencies and transfer across concepts. Existing methods often overemphasize either the sequential evolution of knowledge or the static structural dependencies among concepts. This limitation reduces their ability to dynamically capture the update and transfer of knowledge during learning. In knowledge tracing, dynamic knowledge modeling mainly relies on students’ response interactions to update concept representations. However, due to the sparsity and potential noise in students’ response records, concept representations updated solely through interaction data are often insufficiently learned. As a result, the dynamic modeling process becomes unstable since it fails to capture the intrinsic semantic characteristics of the knowledge concepts. Based on these analyses, knowledge tracing currently faces two main challenges: First, how to jointly model the evolution of student knowledge and the structural dependencies among concepts to dynamically capture knowledge updates and transfer. Second, how to construct stable and reliable knowledge representations under sparse interaction data.

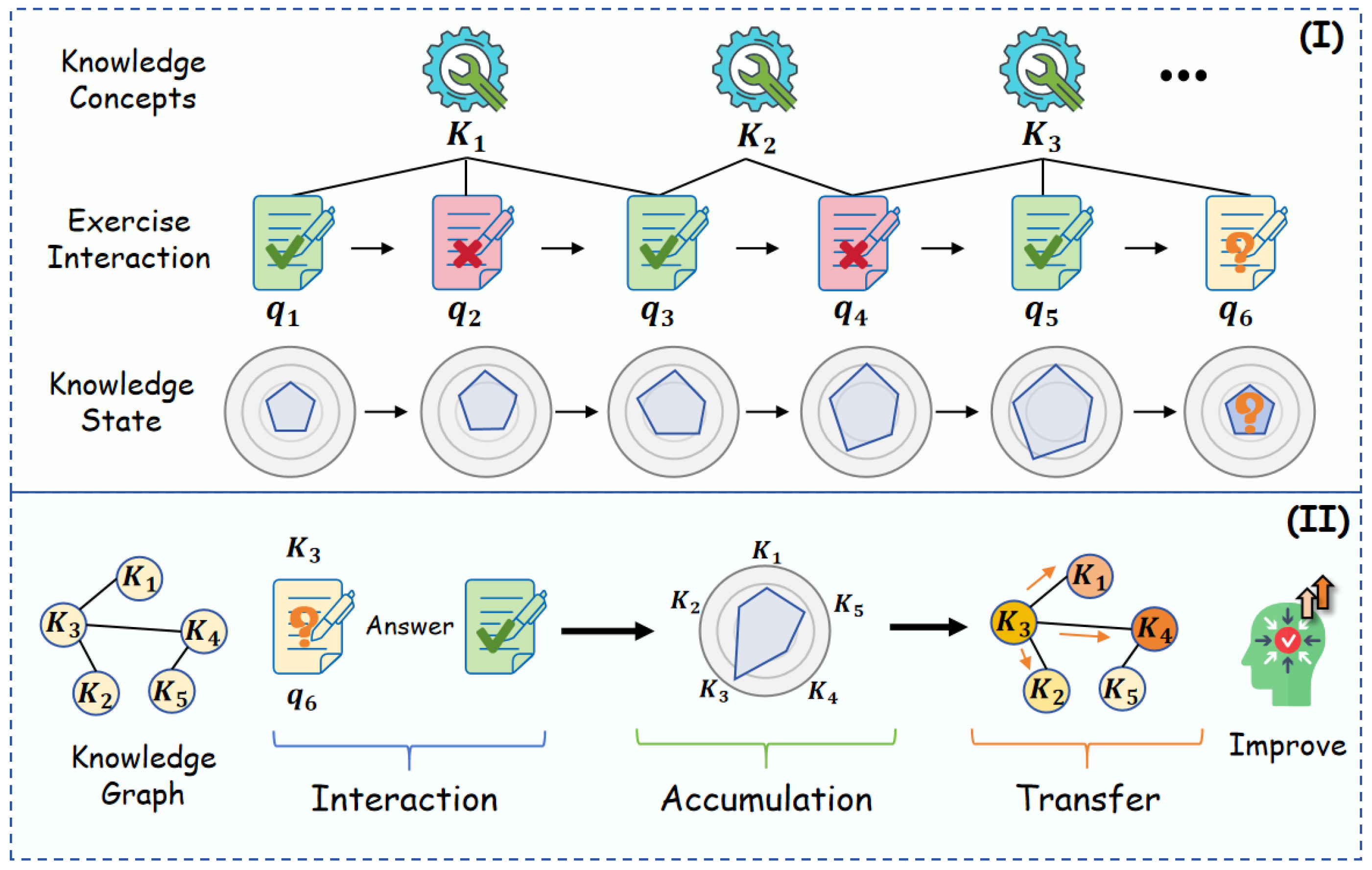

To address these challenges, we propose a novel knowledge tracing model DyGAS, which dynamically integrates sequential knowledge modeling with graph-based structural modeling to simulate students’ knowledge evolution through an interaction–knowledge accumulation–knowledge transfer process (illustrated in

Figure 1). Here, interaction refers to students’ problem-solving behaviors, knowledge accumulation refers to the acquisition of knowledge gains from exercises, and transfer refers to the students’ ability to transfer and extend the learned knowledge. The sequential module models the process of acquiring knowledge gains from each interaction and dynamically integrates short-term learning gains with long-term knowledge accumulation, thereby mitigating knowledge forgetting. The structural module employs graph convolutional networks to capture dependencies among concepts, thereby modeling the process of knowledge transfer. To alleviate instability caused by sparse interactions, DyGAS additionally incorporates a static knowledge module, which constructs static embeddings by aggregating features from all exercises associated with each concept. This process captures the inherent semantic information of each concept, independent of students’ interaction patterns. The static embeddings thus act as semantic priors, stabilizing concept representations under conditions of sparse interactions. Finally, DyGAS adaptively fuses multiple knowledge representations to model students’ knowledge states more comprehensively.

Our contributions are as follows:

We propose a novel knowledge tracing model DyGAS. It integrates sequential and graph-based modeling. The sequential module captures knowledge acquisition and forgetting, while the structural module captures dependencies and knowledge transfer across concepts, together effectively simulating students’ knowledge evolution.

To mitigate instability caused by sparse interactions, DyGAS incorporates static knowledge modeling within the structural module, providing semantic priors for knowledge concepts. This complementary perspective ensures stable representations for concepts and strengthens the structural modeling of inter-concept dependencies.

DyGAS significantly improves predictive accuracy. Extensive experiments on three benchmark datasets demonstrate its superiority over state-of-the-art methods.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related work.

Section 3 introduces the preliminaries.

Section 4 presents the proposed method, DyGAs, in detail.

Section 5 describes the algorithm implementation and provides the computational complexity analysis.

Section 6 reports the experimental results. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Knowledge tracing (KT) aims to capture how students’ knowledge evolves throughout the learning process and to predict their performance on subsequent concept-related tasks. Early studies in this field can be traced back to Bayesian knowledge tracing [

7] and factor analysis approaches [

20,

21,

22]. With the emergence of deep learning, KT has enabled more fine-grained and dynamic modeling of students’ knowledge states. Deep learning-based KT approaches can be grouped into four categories based on their modeling strategies: sequential, memory, attention, and graph.

Sequential-based methods leverage recurrent neural networks to effectively capture the temporal dependencies and evolving dynamics in students’ learning processes. DKT [

8] is the first to introduce recurrent neural networks into knowledge tracing, modeling students’ evolving knowledge states through sequential dependencies. Building on this foundation, DKT+ [

23] incorporates reconstruction errors to stabilize knowledge states, while DKT+forgetting [

24] accounts for knowledge decay during the learning process. ATKT [

25] leverages adversarial training to improve generalization. LPKT [

9] further emphasizes consistency between students’ knowledge states and their learning process. DIMKT [

10] incorporates question difficulty into KT, enabling adaptive updates according to problem difficulty. LBKT [

26] extends KT by modeling multiple learning behavior features.

Memory-based methods introduce an external memory component, which enables the model to store and update concept-level knowledge states explicitly. DKVMN [

11] introduces a dynamic key-value memory network to model the relationships between concepts and track each student’s evolving mastery over them. SKVMN [

12] extends DKVMN by integrating sequential modeling to better capture dependencies in students’ exercise histories. DGMN [

13] introduces a forget-gated attention memory network to model students’ forgetting behaviors and dynamically capture relationships among latent concepts. MAN [

27] combines memory-augmented and attention-based networks with a context-aware attention mechanism to model both long-term and short-term knowledge.

Attention-based methods leverage self-attention mechanisms to alleviate the long-term dependency problem, enabling more flexible modeling of historical interactions and their varying importance. SAKT [

28] was the first model to utilize a self-attention mechanism to assess the influence of past interactions on students’ concept mastery when constructing their knowledge states. SAINT [

14] employs an encoder-decoder transformer to model exercises and responses separately. AKT [

15] introduces a context-aware monotonic attention mechanism to model the influence of past responses. ELAKT [

29] extends AKT by incorporating causal convolutions and a prediction correction module to better capture local knowledge dynamics and handle stochastic student behaviors. SparseKT [

30] introduces a sparsification mechanism to focus on the most relevant student interactions.

Graph-based methods utilize graph neural networks [

31,

32,

33] to capture complex structural relationships among concepts and exercises, thereby modeling inter-concept dependencies beyond sequential information. GKT [

16] represents exercises and concepts in a graph and applies graph neural networks to propagate knowledge states, thereby capturing inter-concept dependencies more effectively. SKT [

34] models concept influence propagation, considering both directed and undirected relations. HGKT [

35] builds a hierarchical exercise graph to capture complex dependencies and models both knowledge and problem schema for improved tracing and interpretability. GIKT [

17] leverages a graph convolutional network to model high-order question-skill interactions and captures long-term dependencies in students’ exercise histories. DGEKT [

18] models heterogeneous exercise–knowledge relationships using a dual graph structure and combines them via knowledge distillation. DyGKT [

19] employs dynamic graph learning with a dual time encoder to model evolving student–question–concept relationships in continuous time. L-SKSKT [

36] integrates long- and short-term knowledge state representations via graph embeddings to enhance knowledge tracing and capture learning preferences.

Our method lies at the intersection of sequential and graph-based approaches, combining sequential modeling of student interactions with structural modeling over knowledge concepts. Unlike prior works that emphasize either sequential dynamics or structural dependencies, our framework explicitly integrates both perspectives. Specifically, it simulates knowledge evolution through an interaction–knowledge accumulation–knowledge transfer process. The sequential module captures short- and long-term learning dynamics, while the graph module models inter-concept dependencies and transfer. This hybrid design provides a comprehensive representation of students’ knowledge states. Through this unified perspective, our approach improves knowledge tracing by effectively bridging sequential and structural paradigms and providing an effective framework for modeling students’ dynamic learning processes.

3. Preliminary and Notation

Let

denote the set of students in an online learning system, where

I is the total number of students. Each student

has a sequence of interaction records

where

T denotes the maximum length of the interaction sequence,

represents an exercise,

denotes the associated knowledge concepts, and

is the student’s response outcome (one for correct and zero for incorrect). Exercises and knowledge concepts follow a many-to-many relationship, one exercise may involve multiple knowledge concepts, and one concept may correspond to multiple exercises. Let the relations between exercises and knowledge concepts be represented by a binary association matrix

, where

if exercise

involves knowledge concept

, and

otherwise. Typical symbols are summarized in

Table 1.

Given a student’s learning history up to time t, the task of knowledge tracing is to predict the probability that student will correctly answer the next exercise .

4. Proposed Method: DyGAS

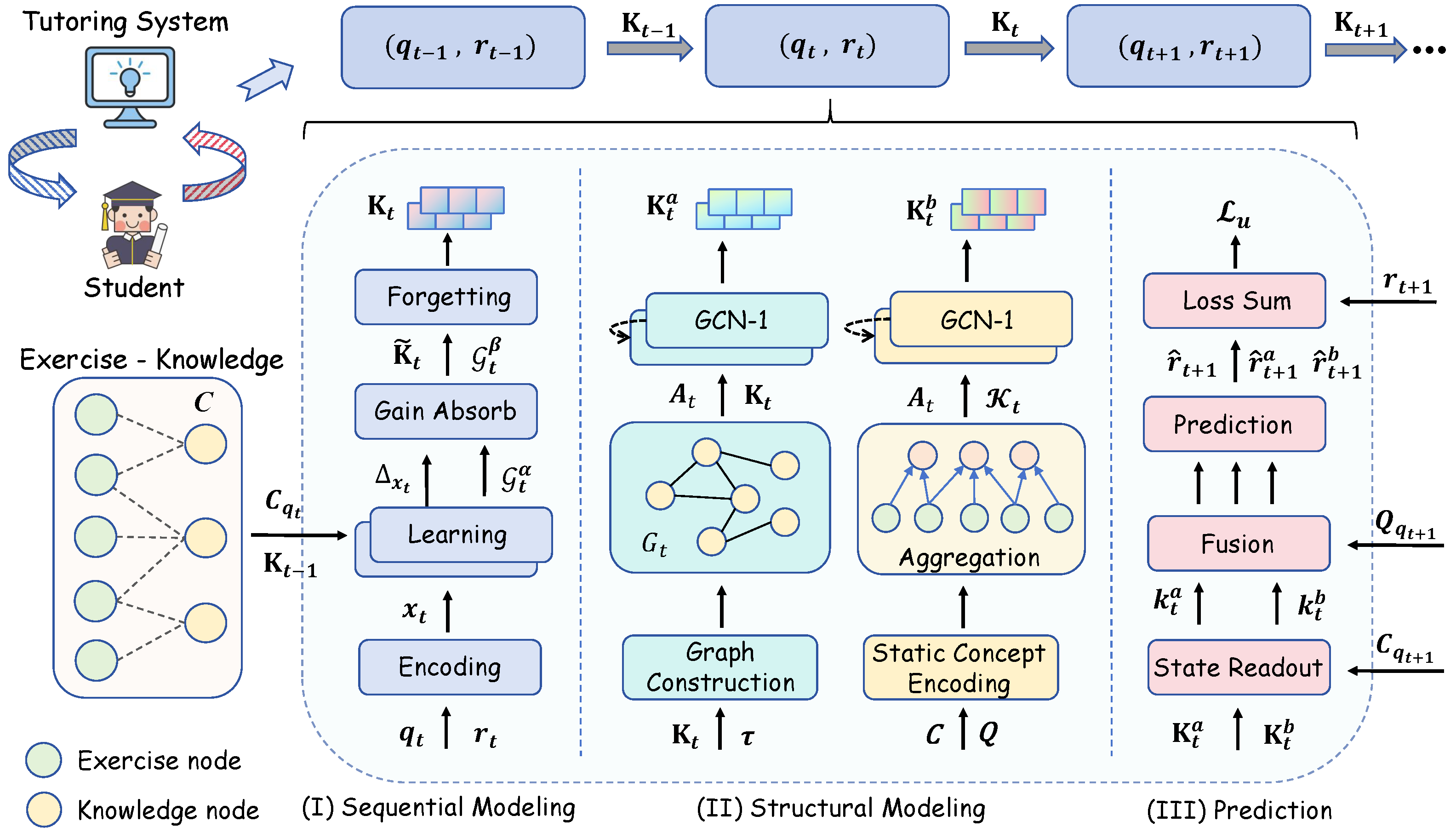

In this section, we provide a detailed overview of the DyGAS model, for which overall architecture is illustrated in

Figure 2. DyGAS combines sequential modeling with graph-based structural reasoning to capture both the evolution of students’ knowledge states and the dependencies among concepts. We first describe sequence modeling of student interactions to capture knowledge gains from exercise responses. Next, we use graph convolutional networks to model students’ current knowledge states from both dynamic and static perspectives. Finally, we explain how DyGAS predicts student responses based on these knowledge representations.

4.1. Embedding

Let

denote the exercise embedding matrix,

the knowledge embedding matrix,

N is the total number of questions,

M is the total number of concepts, and

d is the embedding dimension. At time step

t, a student’s interaction is denoted as

, where

is the attempted exercise and

indicates whether the response is correct. To explicitly distinguish between correct and incorrect responses, we construct the interaction embedding as

where

denotes vector concatenation. A linear layer is then applied to fuse the exercise and correctness information:

where

and

. The resulting embedding

constitutes the input representation for the model.

4.2. Sequential Knowledge Modeling

In knowledge tracing tasks, a student’s knowledge state is not static but evolves dynamically with each interaction. To capture this evolution, we model the sequence of student responses, which allows the model to account for both short-term performance fluctuations and long-term knowledge accumulation. At each time step, the model integrates the current exercise response with the previous knowledge state, thereby updating the representation of the student’s knowledge in a context-aware manner. Specifically, to derive the knowledge state

associated with the current exercise

, we retrieve the corresponding concept embedding from the previous embedding matrix

:

where

is the row of

corresponding to exercise

, representing the set of associated knowledge concepts. We then compute the interaction gain

by combining the previous interaction embedding

, the current interaction embedding

, and the retrieved knowledge state

:

where

are learnable parameters, and

denotes the hyperbolic tangent activation function. To control the extent to which the student absorbs

, we also introduce a absorption gate

:

where

are learnable parameters, and

denotes the sigmoid activation function. The knowledge gain is then obtained by modulating the interaction gain with the gate:

To update the knowledge state, we further design a forgetting gate

that determines how much of the previous knowledge should be retained for each knowledge concept:

where

denotes the knowledge embedding matrix before the update, and

are learnable parameters. The updated knowledge embedding is then given by:

This module ensures that the model not only injects gated learning gains into the embeddings of relevant concepts, but also dynamically regulates the balance between long-term knowledge accumulation and short-term learning gains through the forgetting gate mechanism.

4.3. Structural Knowledge Modeling

Although sequence modeling can capture the sequential evolution of a student’s knowledge, it neglects the complex dependencies among knowledge concepts. In fact, certain concepts are often interrelated. Mastering one concept may facilitate understanding of related concepts, reflecting a natural knowledge transfer process in students’ learning. To capture the structural dependencies among knowledge concepts, we adopt a graph-based approach to model students’ knowledge states. Specifically, knowledge concepts are represented as nodes and their relationships as edges, allowing the model to propagate information across related concepts. This approach not only integrates the learning gains obtained from prior interactions but also generates a richer and more structured representation of the knowledge state.

4.3.1. Knowledge Graph Construction

To capture the structural dependencies among knowledge concepts, we construct a dynamic knowledge graph representing the current structural relationships of the student’s knowledge. Formally, we define the graph as the following:

where

denotes the set of

M knowledge concepts, and each node

corresponds to the embedding

of the concept.

represents the set of edges, capturing pairwise dependencies among concepts. Specifically, the edge weight between concepts

and

is defined using the cosine similarity of their embeddings:

The adjacency matrix

is then obtained by a threshold of similarity scores:

where

is a predefined similarity threshold. This procedure ensures that edges are established only between sufficiently related concepts, allowing information to propagate selectively during graph convolution.

4.3.2. Dynamic Knowledge Modeling

Given the constructed dynamic knowledge graph

, we adopt a graph convolutional network to model the structural dependencies among concepts. In this network, each concept node updates its representation by aggregating information from its neighbors along the graph edges, which implements a standard message-passing operation. Specifically, the knowledge embeddings

serve as the initial node features

. At the

-th graph convolution layer, the concept representations are updated by aggregating information from their neighbors:

where

also is the adjacency matrix with self-connections,

is its degree matrix,

is a learnable weight matrix, and

denotes a nonlinear activation function. The resulting

encodes the dynamically updated knowledge representations, reflecting the structural dependencies among concepts.

4.3.3. Static Knowledge Modeling

Dynamic knowledge modeling is highly dependent on students’ interaction sequences, making the derived concept embeddings susceptible to sparsity and instability, especially for concepts with few interactions. Moreover, such modeling primarily reflects students’ learning dynamics but overlooks the intrinsic semantic information carried by the concepts themselves. To address this limitation, we construct static knowledge embeddings by aggregating the features of all exercises associated with each knowledge concept. Specifically, for concept , we compute the fused embedding of all corresponding exercises to obtain a stable and semantically enriched feature. Static knowledge embeddings serve as stable semantic priors that preserve each concept’s intrinsic meaning. This design enhances concept representations under sparse interactions and improves the robustness of knowledge transfer. Formally, building upon the defined association matrix and exercise embedding matrix , we derive static knowledge embeddings by aggregating exercise features for each concept . Finally, each row of is normalized by the number of exercises associated with the corresponding concept to ensure a consistent scale across concepts.

While the node features are derived from the static knowledge embeddings

, we still use the dynamically constructed adjacency matrix

to capture the structural relationships among concepts. This design allows the model to combine stable, semantically enriched node features with the time-varying relational patterns observed in students’ interactions. Each concept node updates its representation by aggregating information from its neighbors according to

:

where

denotes the adjacency matrix with self-loops,

is the corresponding degree matrix, and

is a learnable weight matrix.

4.4. Prediction and Training

Given the obtained dynamic knowledge embeddings

and static knowledge embeddings

, we first identify the set of concepts associated with the next exercise

. For each perspective, the corresponding exercise-specific knowledge state is derived as the following:

where

is the exercise-concept association vector. To generate the prediction, we concatenate the dynamic state

, the static state

, and the embedding of the target exercise

. The combined representation is then projected through a linear transformation followed by the sigmoid function:

where

and

are learnable parameters, and

denotes the sigmoid function. Here,

represents the predicted probability that the student answers

correctly.

To encourage each knowledge perspective to learn discriminative representations independently, we also perform auxiliary predictions based on the dynamic and static knowledge states. Specifically, these knowledge states are separately mapped to the probability of correctly answering

:

where

and

are learnable parameters. For each prediction, the binary cross-entropy loss is computed with respect to the ground-truth labels

:

where

T is the number of valid time steps. The model is trained by minimizing the joint loss

:

where

,

control the relative contribution of the auxiliary losses to the total objective, enabling a flexible trade-off between the main and auxiliary objectives.

5. Algorithm Implementation and Computational Complexity Analysis

To provide a clear overview of the training procedure of DyGAS, we summarize it in Algorithm 1. We further analyze the computational complexity of the proposed model DyGAS. In the Sequential Knowledge Modeling, the student’s knowledge state is updated at each time step by integrating the previous interaction embedding, the current exercise embedding, and the retrieved knowledge state of associated concepts. This process involves linear transformations applied to concatenated vectors for computing the interaction gain and absorption gate, as well as the forgetting gate , which modulates the retention of the previous knowledge state. Each of these transformations contributes complexity per operation, and since the forgetting gate is applied across M knowledge concepts, it incurs an additional . Multiplication with the exercise–concept association vector of size M to update the embeddings of the associated concepts contributes . Consequently, the complexity of this sequential module is .

The Structural Knowledge Modeling captures dependencies among knowledge concepts through graph-based aggregation, considering both dynamic and static perspectives. In the dynamic perspective, at each time step, the adjacency matrix is constructed by computing pairwise cosine similarities among M knowledge concept embeddings, incurring complexity. This adjacency matrix is then normalized using degree-based scaling, contributing an additional complexity, and is subsequently used in a graph convolution that first maps the node features via a weight matrix () and then aggregates neighbor information (), resulting in a total complexity of . Consequently, the per-step complexity of the dynamic modeling is . In the static perspective, knowledge embeddings are precomputed by aggregating the features of all associated exercises, with a cost of , where N is the total number of exercises, while the graph convolution still needs to be applied per time step, resulting in the same per-step complexity . The total computational cost of the Structural Knowledge Modeling module is , where the first term accounts for per-step graph convolution computations and adjacency construction, and the second term corresponds to the static feature aggregation.

In the Prediction and Training module, the model first derives exercise-specific knowledge states by multiplying the exercise–concept association vector with the dynamic and static knowledge embeddings, respectively. This projection operation contributes complexity. The obtained representations, together with the embedding of the target exercise, are concatenated and passed through a linear transformation to produce the main prediction, which incurs complexity. In addition, auxiliary predictions are computed by concatenating the exercise embedding with either the dynamic or the static knowledge state, each followed by a linear transformation, which incurs complexity. Consequently, the overall complexity of this prediction module is .

Considering all components of the DyGAS model, the overall computational complexity is dominated by the structural knowledge modeling. Specifically, the sequential knowledge updates contribute a lower-order term of

per time step, and the prediction module contributes

per step, both of which are negligible compared to the graph-based computations. The structural knowledge modeling requires

operations per step for adjacency construction and graph convolution, and the static knowledge aggregation contributes

. Therefore, the total computational cost of the model over a sequence of length

T can be expressed as

, where the first term accounts for the per-step graph convolution, and the second term corresponds to the static feature aggregation.

| Algorithm 1 Training process of DyGAS. |

- Require:

Student interaction history , exercise–knowledge matrix , embedding dimension d, training steps T, loss weights . - 1:

Initialize model parameters . - 2:

for not convergence do - 3:

for , … , do - 4:

Encode interaction into embedding (Equation ( 1)). - 5:

The sequential model updates knowledge state via gated evolution (Equations ( 2)–( 7)). - 6:

Construct dynamic knowledge graph with threshold (Equations ( 8) and ( 9)). - 7:

The structural model applies GCN to obtain dynamic embeddings (Equation ( 10)). - 8:

Aggregate exercise–knowledge relations and apply GCN to learn static embeddings (Equation ( 11)). - 9:

Fuse dynamic and static embeddings to predict (Equations ( 12) and ( 13)). - 10:

Compute auxiliary predictions (Equation ( 14)). - 11:

end for - 12:

Calculate losses (Equations ( 15)–( 17)). - 13:

Update parameters by minimizing (Equation ( 18)). - 14:

end for - 15:

return trained parameters

|

6. Experiments

In this section, we conduct a series of experiments to address the following questions:

RQ1: How does DyGAS perform compared with baseline methods based on different knowledge modeling strategies?

RQ2: What is the impact of each component of DyGAS on the overall performance?

RQ3: Can DyGAS effectively track the evolution of students’ knowledge?

RQ4: How sensitive is DyGAS to the choice of hyperparameters?

RQ5: What is the time complexity of DyGAS?

RQ6: Can DyGAS learn discriminative representations of exercises?

6.1. Datasets

We assess the effectiveness of the proposed model on three real-world public datasets. The overall statistics are reported in

Table 2, and their details are summarized as follows:

ASSIST2009 (

https://sites.google.com/site/assistmentsdata/home/2009-2010-assistment-data, accessed on 1 November 2025). A widely used benchmark dataset collected from U.S. high school students’ online learning activities. It contains students’ response logs, exercise content, and personal information, enabling the analysis of learning patterns, knowledge hierarchies, and performance prediction.

Junyi (

https://pslcdatashop.web.cmu.edu/DatasetInfo?datasetId=1198, accessed on 1 November 2025). Collected from the Junyi Academy, a large-scale online learning platform, this dataset provides detailed student interaction logs. It records not only practice behaviors but also rich exercise-related information, including names, availability, prerequisite relations, knowledge map positions, and creation dates.

Table 2.

Statistics of the datasets.

Table 2.

Statistics of the datasets.

| Statistics | Datasets |

|---|

| |

ASSIST2009

|

ASSIST2017

|

Junyi

|

|---|

| Records | 297,343 | 942,816 | 4,316,340 |

| Learners | 3006 | 1709 | 1000 |

| Exercises | 9798 | 3162 | 701 |

| Concepts | 107 | 102 | 39 |

6.2. Baselines

We conduct comparisons against several representative state-of-the-art baselines, which can be categorized into five groups: traditional, sequential, memory, attention, and graph methods.

BKT (Traditional) models students’ mastery of knowledge concepts via hidden Markov models [

7].

DKT (Sequential-based) leverages recurrent neural networks to model students’ knowledge dynamics over time [

8].

DKVMN (Memory-based) uses a key-value memory architecture to model and update a student’s mastery level for each knowledge concept [

11].

SAKT (Attention-based) employs a self-attention mechanism to selectively model the influence of relevant past exercises [

28].

AKT (Attention-based) leverages a monotonic attention mechanism to capture students’ knowledge evolution [

15].

HiTSKT (Attention-based) uses a hierarchical transformer with session- and interaction-level encoders to capture students’ knowledge dynamics [

37].

GKT (Graph-based) leverages graph neural networks to model the latent relationships among knowledge concepts [

16].

GIKT (Graph-based) employs graph convolutional networks to model high-order exercise–knowledge correlations and student–exercise interactions, effectively capturing long-term dependencies [

17].

DGEKT (Graph-based) constructs a dual graph structure to capture heterogeneous exercise-concept relations and interaction transitions [

18].

L-SKSKT (Graph-based) models both long- and short-term student knowledge states using graph-based embeddings [

36].

6.3. Experiments Setup and Evaluation Metrics

The DyGAS model was implemented in PyTorch 1.1 [

38] with a learning rate set to 0.001 and a batch size of 64. To mitigate overfitting, we applied L2 weight decay of 1 × 10

−5 and a dropout rate of

. All sequences were standardized to a fixed length of 100 time steps (

) by truncation or padding. In each dataset, 80% of sequences were allocated for training and the remaining 20% for testing [

39,

40]. The embedding dimension

d was selected from {16, 32, 64, 128, 256}, the similarity threshold

, used for constructing the knowledge graph, was varied from zero to one in steps of 0.1, and the auxiliary loss balancing parameters

and

were varied from zero to one in increments of 0.2. The influence of these hyperparameters on model performance is discussed in hyperparameter sensitivity analysis.

We evaluated the performance of our model using three commonly adopted metrics in knowledge tracing tasks [

41,

42,

43,

44]: area under the curve (AUC), accuracy (ACC), and root mean square error (RMSE). Both AUC and ACC range between zero and one, where larger values indicate better predictive performance. RMSE also falls within the 0–1 range, with smaller values reflecting lower prediction error and thus more accurate predictions.

6.4. Overall Comparision (RQ1)

Table 3 reports the performance comparison between DyGAS and all baselines, where the best and second-best results are marked in bold and underline, respectively. Overall, DyGAS achieves the strongest performance on all three datasets, substantially surpassing baselines from traditional, sequential, memory, attention, and graph neural network paradigms. Compared with the strongest competitor L-SKSKT, DyGAS obtains remarkable improvements: on ASSIST2009, it boosts AUC by 4.61% and reduces RMSE by 8.45%; on ASSIST2017, it raises ACC by 1.19% and lowers RMSE by 2.02%; and on the large-scale Junyi dataset, it still secures consistent gains across all metrics, including a 0.86% reduction in RMSE.

Specifically, BKT relies on an overly simplistic Markov assumption, making it difficult to capture the dynamic evolution of students’ knowledge. Although DKT, as a sequential model, can track knowledge changes over time, it depends solely on a single sequential state representation. In contrast, DyGAS’s sequential modeling leverages memory gating to dynamically integrate short-term knowledge gains with long-term accumulation, resulting in superior performance compared to these methods. DKVMN’s memory mechanism maintains the mastery state of students’ knowledge, but for concepts with few associated interactions, the knowledge state is updated infrequently, limiting the model’s ability to track learning progress. DyGAS addresses this by incorporating static knowledge modeling, providing stable semantic information to compensate for infrequent knowledge updates from sparse interactions. SAKT and AKT highlights relevant past responses through self-attention, and HiTSKT employs a hierarchical transformer to capture session- and interaction-level dynamics. However, these attention-based methods often overlook the inherent structural relationships among knowledge concepts. In contrast, DyGAS leverages graph-based modeling to capture such complex dependencies, resulting in more accurate and comprehensive modeling of knowledge structures. GKT excels at capturing static dependencies between knowledge concepts, GIKT models higher order exercise–knowledge relations, DGEKT constructs graphs and hypergraphs to capture exercise–knowledge associations, and L-SKSKT employs graph neural networks to represent both long- and short-term knowledge states. However, these methods generally emphasize global or static structures and lack dynamic modeling of students’ knowledge evolution over time. By integrating sequential and graph-based modeling, DyGAS captures knowledge dependencies and dynamically tracks students’ knowledge evolution, achieving state-of-the-art performance on all three datasets.

6.5. Ablation Study (RQ2)

Table 4 presents the ablation study of DyGAS across three datasets. Five model variants are evaluated to examine the contribution of different components. (1) Auxiliary loss (AU): Omitting the auxiliary loss leads to a slight decline in AUC and ACC across all datasets, accompanied by a minor increase in RMSE. This suggests that the auxiliary objectives contribute to more discriminative representation learning for each knowledge aspect independently, which in turn helps capture informative features that enhance predictive performance. (2) Dynamic knowledge modeling (DM): Removing this component results in a noticeable decline in performance. This indicates that integrating a dynamic knowledge graph over knowledge concepts facilitates the transfer of knowledge between related concepts, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to capture evolving knowledge states. (3) Static knowledge modeling (SM): Removing the static knowledge component consistently degrades performance. Static embeddings serve as stable semantic priors that complement sparse interaction data, particularly for knowledge concepts with limited associated exercises. In the absence of static modeling, the concept representations learned solely from dynamic sequences become more susceptible to sparsity and instability, reducing the model’s overall predictive reliability. (4) Entire structural knowledge modeling (AL): Removing all structure-related components, including dynamic and static knowledge modeling as well as auxiliary supervision, leads to the largest performance drop. This highlights the critical role of graph-based structural modeling in capturing inter-concept dependencies, propagating knowledge gains. Without this component, the model relies solely on sequential knowledge modeling, losing the ability to represent the relational structure of knowledge and thereby weakening its capacity to model students’ knowledge states. (5) Forgetting gate (FG): Removing the forgetting gate results in a notable decrease in performance. This mechanism enables the model to selectively retain or decay historical knowledge when integrating it with the current interactions, thereby facilitating the adaptive fusion of long-term and short-term knowledge states. Overall, the findings confirm that all components are effective and contribute to the model’s ability to capture evolving knowledge states and inter-concept dependencies.

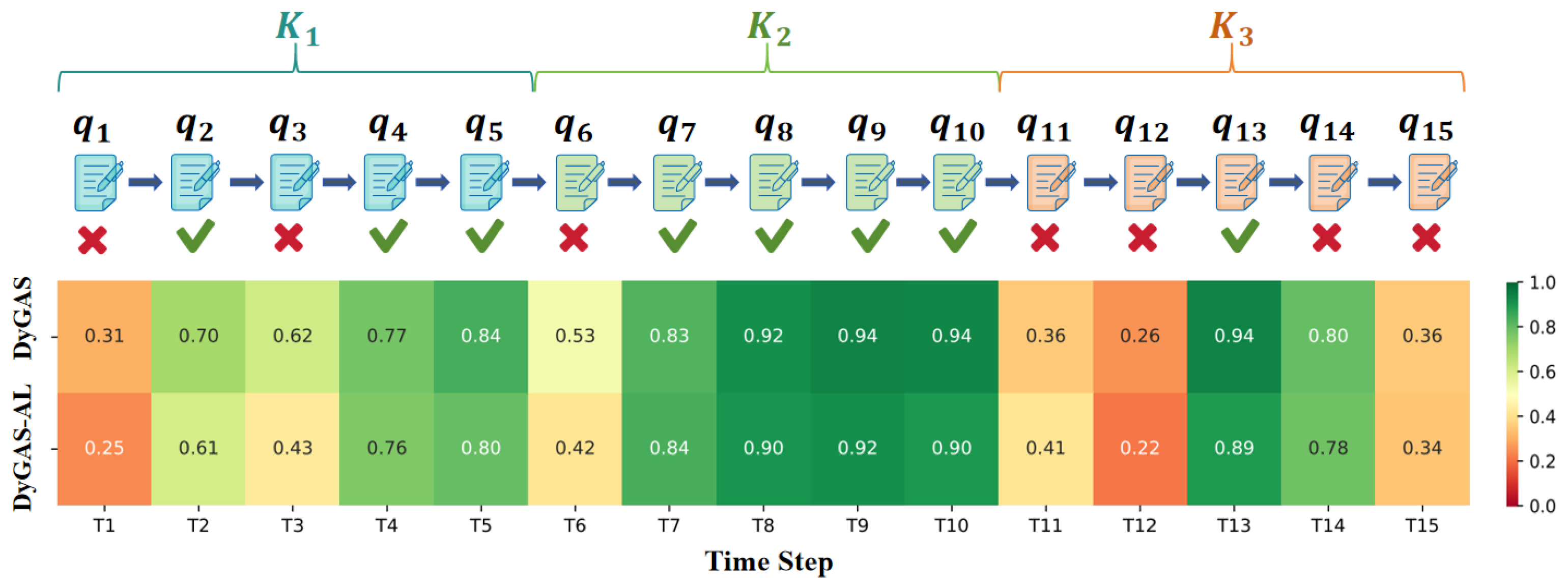

6.6. Visualization of Knowledge Evolution (RQ3)

We further analyze an instance to understand how our model captures a student’s evolving knowledge state over a sequence of 15 exercises, as shown in

Figure 3. For example, consider the evolution of knowledge concept

across exercises T1–T5. At T1, the student answers incorrectly, and the corresponding prediction probability is 0.31, indicating a limited initial understanding. Following a correct response on T2, the probability sharply rises to 0.70, reflecting knowledge acquisition. At T3, despite an incorrect response, the probability remains relatively high (0.62) compared to T1, suggesting that the student preserves previously accumulated knowledge. Subsequent correct responses at T4 and T5 lead to further increases in prediction probabilities (0.77 and 0.84), demonstrating continued knowledge consolidation. For knowledge concept

, the student initially shows weak mastery, with low prediction probabilities at

and

. After correctly answering

, the probability sharply rises to 0.94, reflecting a strong positive update from this success. Although the student answers incorrectly at

, the probability remains relatively high (0.80), suggesting that the model retains the influence of the accumulated knowledge from the prior correct response. However, the subsequent error at

reduces the probability back to 0.36, indicating a decline in the student’s estimated mastery level after consecutive mistakes. Comparing DyGAS with the DyGAS-AL variant predictions, we observe that DyGAS consistently produces slightly higher prediction probabilities. For instance, at T2 and T10, where the student answers correctly, DyGAS predicts probabilities of 0.70 and 0.94, respectively, whereas DyGAS-AL predicts 0.61 and 0.90. This difference arises because DyGAS leverages the structural relationships among knowledge concepts: knowledge gains in one concept can positively influence related concepts. In contrast, DyGAS-AL relies solely on sequential interactions, which captures sequential patterns but may underestimate the accumulated knowledge due to the lack of structural context. Therefore, DyGAS can reflect the probability of correct responses, especially for knowledge concepts that benefit from related prior learning.

This analysis demonstrates that our model effectively tracks the dynamic evolution of a student’s knowledge state. By capturing structural relationships among knowledge concepts, DyGAS not only reflects accumulated knowledge states but also enhances the modeling of concepts influenced by related knowledge, highlighting the important role of structural knowledge modeling in knowledge tracing.

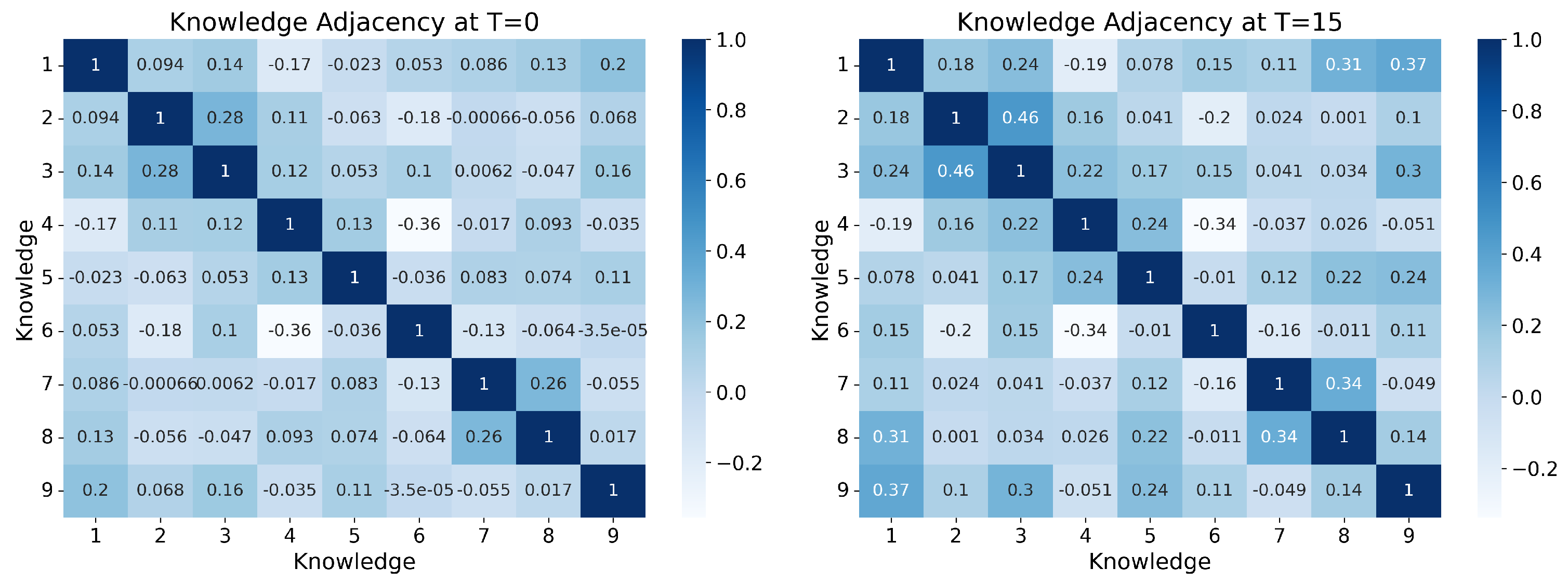

Figure 4 further illustrates how mastery of certain concepts positively influences related concepts as the student progresses through the exercises.

6.7. Hyperparameter Sensitivity Analysis (RQ 4)

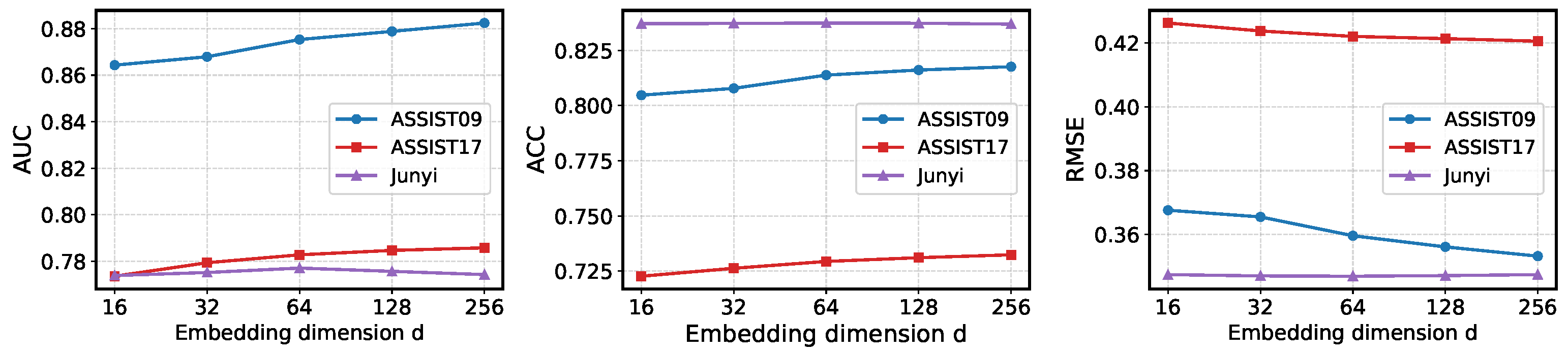

In this section, we investigate the impact of key hyperparameters on the performance of DyGAS, including the feature embedding dimension d, the association threshold for constructing the dynamic knowledge graph, and the balance coefficients of the auxiliary losses, and .

Impact of

d. The effect of feature embedding dimension on DyGAS is shown in

Figure 5. For ASSIST2009 and ASSIST2017, increasing

d generally leads to improvements in AUC and ACC, while RMSE decreases, indicating more accurate predictions. However, the performance gains gradually diminish as

d becomes larger, suggesting that extremely high-dimensional embeddings provide limited additional benefit and may increase computational cost during training. On the Junyi dataset, the impact of

d is less pronounced. Both ACC and RMSE remain relatively stable across different embedding dimensions, while AUC exhibits a slight increase at moderate dimensions and a minor decrease when

d becomes very large. This decline may be attributed to overfitting and the redundancy introduced by excessively high-dimensional embeddings. Overall, these observations suggest that moderate embedding dimensions (e.g.,

or 128) offer a good trade-off between representational capacity and computational efficiency. They are sufficient to capture interactions among exercises and concepts without introducing excessive redundancy or training overhead.

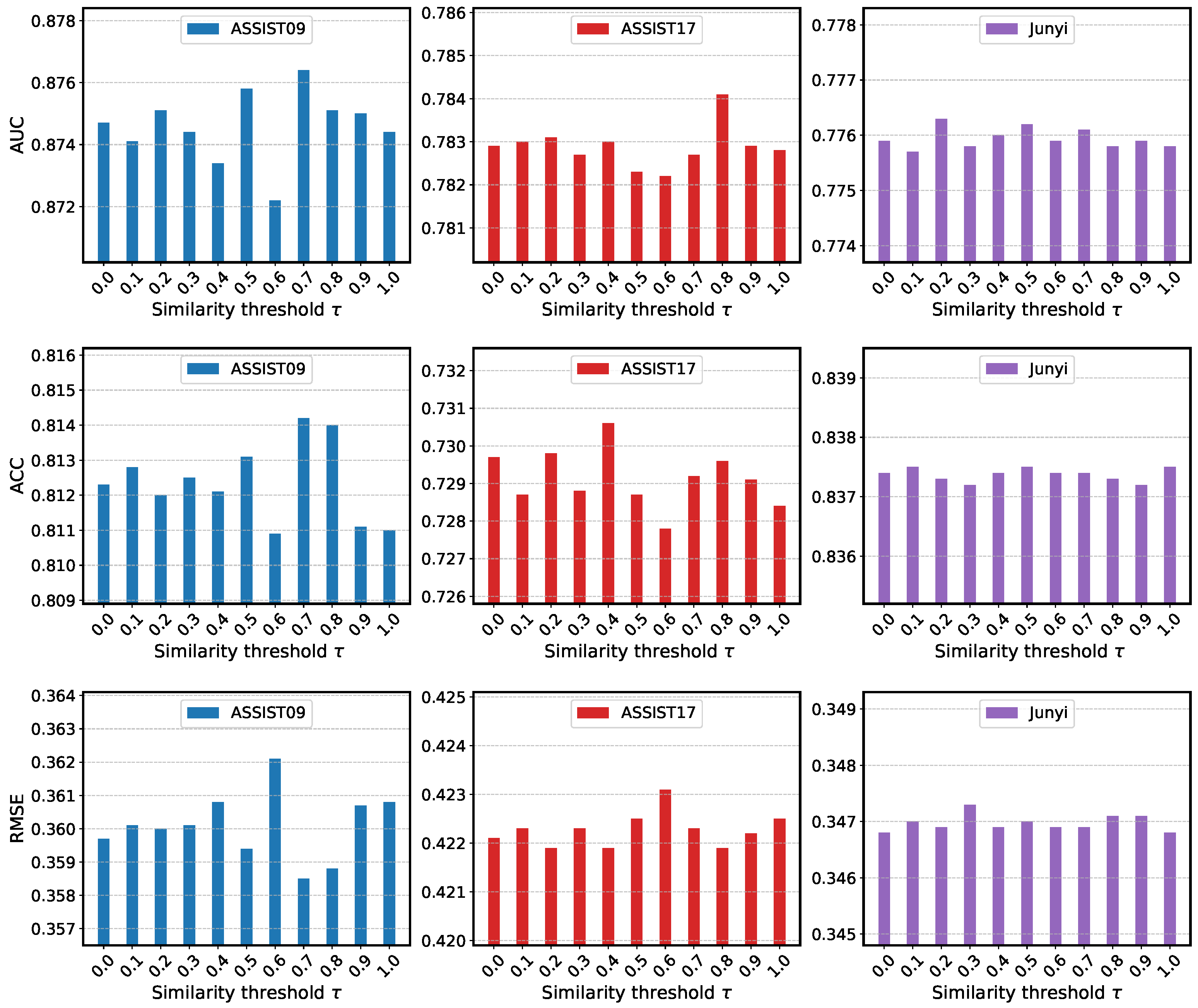

Impact of

. The impact of the similarity threshold

on dynamic knowledge graph construction is reported in

Figure 6. The overall performance is relatively stable when

varies between zero and one. Specifically, on ASSIST2009, higher thresholds (e.g.,

) slightly improve both AUC and ACC while reducing RMSE, suggesting that filtering weaker edges helps the model focus on stronger concept dependencies and yields better structural representations. The results on ASSIST2017 exhibit modest variations, with AUC and ACC fluctuating within a narrow range across thresholds, indicating that the dataset’s relational structure is not highly sensitive to changes in graph sparsity. For Junyi, the metrics remain stable across different thresholds, indicating that its concept relations are relatively independent, so removing weaker edges has little impact on the overall structure. Overall, these results suggest that moderate thresholds (e.g.,

–

) tend to provide a good balance between filtering out noisy edges and preserving meaningful structural relations. While the overall performance remains relatively stable across datasets, ASSIST2009 shows a slight preference for higher thresholds, whereas ASSIST2017 and Junyi exhibit only marginal changes. This indicates that the effectiveness of thresholding is dataset-dependent rather than universally consistent.

Impact of

. To investigate the influence of auxiliary loss weights on DyGAS, we vary

and

over

and report the results in

Table 5. The hyperparameter

controls the contribution of the auxiliary loss associated with the dynamic knowledge state, whereas

regulates the auxiliary loss from the static knowledge state. The results demonstrate a discernible contrast in the impact of the coefficients

and

. The influence of

on predictive performance is relatively subtle. For instance, on ASSIST2009, the optimal AUC and RMSE were achieved at

, with only marginal gains in ACC observed at higher values. Performance on ASSIST2017 and Junyi remained largely stable, with peak metrics occurring at

. This suggests that enhancing the dynamic knowledge contribution through

provides, a limited performance benefit. In contrast,

exhibited a more pronounced and generally positive association with model performance across datasets, highlighting the critical role of the static knowledge perspective. Performance on ASSIST2009 improved monotonically with

, peaking at

. Similarly, on ASSIST2017, optimal results were attained at

, while on Junyi, the highest performance was achieved at

. These observations indicate that the auxiliary loss

effectively strengthens the static concept embeddings, leading to more stable representations and consequently, enhanced predictive accuracy and robustness. Overall, the auxiliary loss parameters provide independent supervision for the dynamic and static knowledge perspectives, helping the model better capture dynamic knowledge evolution and stabilize concept representations.

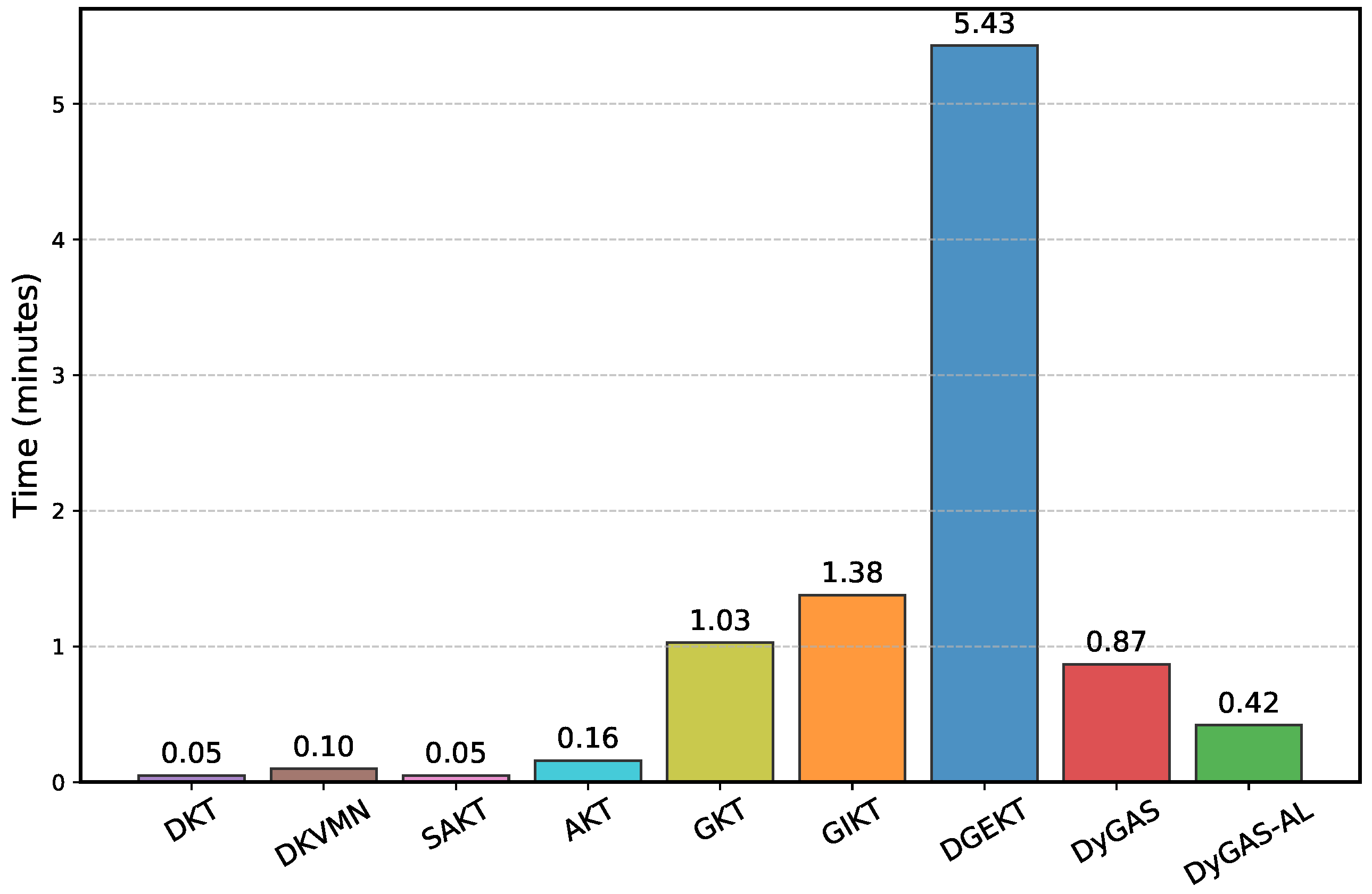

6.8. Comparison on Time Cost (RQ5)

To evaluate the computational efficiency of DyGAS, we report the training time of different knowledge tracing models on the ASSIST2009 dataset (

Figure 7). Runtime is a critical factor for educational applications, where models need to process long interaction sequences quickly. All experiments were conducted on a single NVIDIA RTX 3060 (12GB) GPU with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2673 v4 and 16GB RAM, and the reported runtime reflects the actual wall-clock training time per epoch.

As shown in the results, our proposed model DyGAS is more costly than baselines such as DKT (0.05), DKVMN (0.10), and attention-based models SAKT (0.05), AKT (0.16). However, they are substantially more efficient than graph-based baselines including GKT (1.03), GIKT (1.38), and particularly DGEKT (5.43). This demonstrates that our method achieves a favorable trade-off between incorporating graph relational information and maintaining acceptable runtime. The key reason for this efficiency is that, unlike prior models that explicitly construct and update large-scale exercise graphs or exercise-knowledge graphs, our method restricts graph structural modeling to the knowledge concept level, where the graph is significantly smaller. Modeling dependencies between knowledge concepts is not only computationally lighter but also pedagogically meaningful, as concepts capture the underlying cognitive structures shared across multiple exercises and naturally reflect the knowledge transfer process in student learning. Consequently, the model avoids expensive message passing over thousands of exercise nodes while still preserving the essential relational information for effective prediction. Finally, comparing DyGAS with its variant DyGAS-AL demonstrates the cost of graph-based structural modeling. While DyGAS requires slightly more time, the overhead remains modest and acceptable considering the performance improvements. This confirms that our concept-level graph component introduces only limited additional complexity while significantly enhancing knowledge tracking capability.

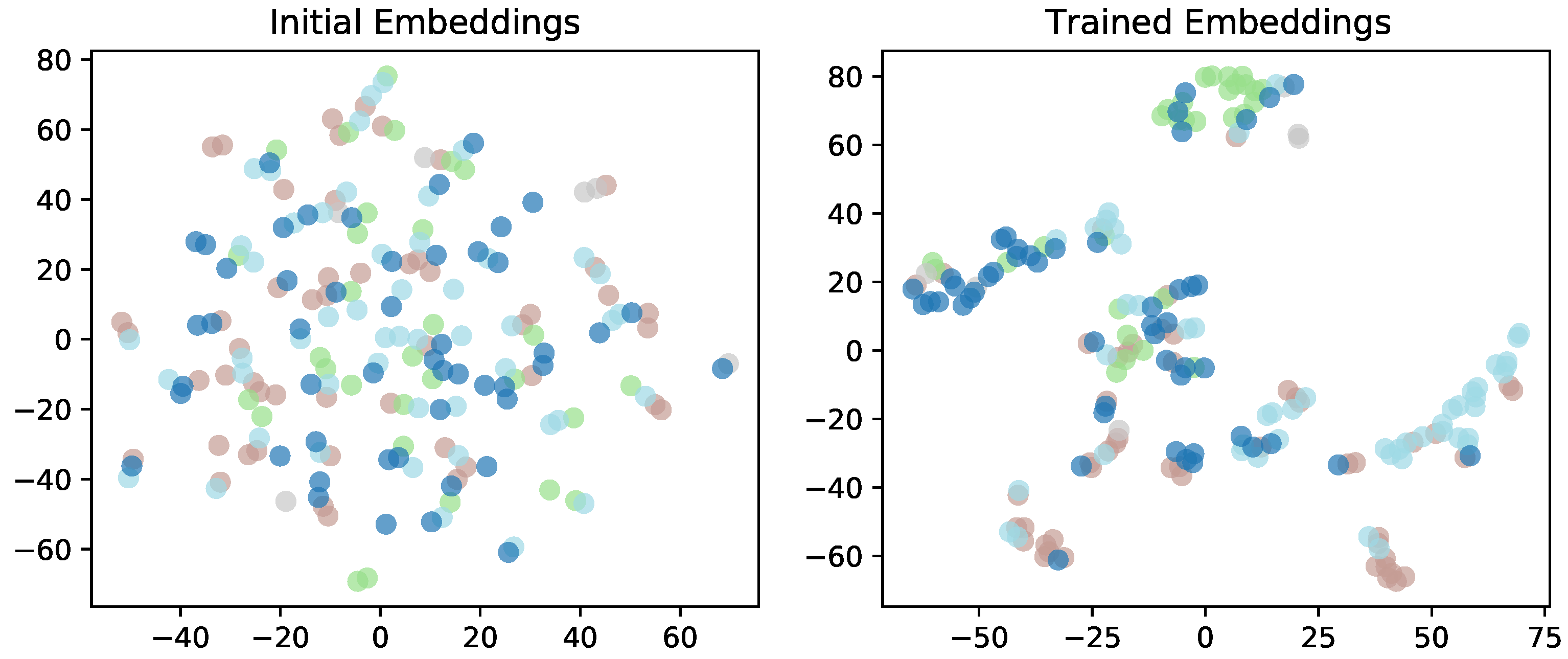

6.9. Exercises Clustering (RQ6)

To investigate whether training can organize question features meaningfully, we conducted the visual experiment on the ASSIST2009 dataset. Specifically, five knowledge concepts are randomly selected and used the corresponding question embeddings as samples. We visualized both the initial and trained question embeddings using the t-SNE method. As shown in the

Figure 8, the initial embeddings are scattered with no obvious clustering, whereas the trained embeddings form more distinct clusters that largely correspond to the labeled knowledge concepts. The questions belonging to the same concept tend to be grouped together, although some clusters are slightly close to each other, which may reflect semantic similarities between concepts or similar question types. These results indicate that, after training, the model has learned more discriminative question embeddings, with questions from the same knowledge concept forming tighter clusters. The proximity between some clusters may reflect potential relationships among knowledge concepts, which may help identify patterns specific to knowledge concepts.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed DyGAS, a novel knowledge tracing model that dynamically integrates sequential modeling with graph-based methods. DyGAS frames the learning process through interaction–knowledge accumulation–knowledge transfer. The sequential module captures knowledge gains from interactions, supporting accumulation, while the structural module leverages graph convolutional networks to model concept dependencies, facilitating knowledge transfer. To mitigate instability caused by data sparsity, we further introduce a static knowledge module into the structural modeling, providing stable semantic priors for knowledge concepts. Experiments on three benchmark datasets demonstrate that DyGAS consistently outperforms state-of-the-art baselines in prediction accuracy. Additional analyses validate the contribution of each module, the robustness of the model under different hyperparameter settings, and its ability to provide interpretable insights into knowledge evolution. Overall, these results suggest that combining sequential dynamics with structural dependencies enables a more comprehensive simulation of students’ knowledge evolution and offers a new perspective for designing knowledge tracing models.

In future work, we plan to explore the adaptability of DyGAS in cold-start or sparse-learning scenarios through meta- or transfer-learning strategies, and further explore its applicability beyond knowledge tracing to broader educational tasks such as personalized content recommendation and adaptive question generation, which could enhance its potential in intelligent learning environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L., Z.Y., Y.G. and S.Y.; methodology, X.L., Z.Y., Y.G. and S.Y.; software, S.Z.; validation, X.L., Z.Y., Y.G., S.Z. and S.Y.; formal analysis, X.L., S.Z. and S.Y.; investigation, S.Y.; resources, X.L.; data curation, X.L.; writing—original draft, X.L., Z.Y., Y.G., S.Z. and S.Y.; writing—review & editing, X.L., Z.Y., Y.G., S.Z. and S.Y.; visualization, X.L., Z.Y., Y.G., S.Z. and S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Siwei Zhou acknowledged the Zhejiang Provincial College Student Science and Technology Innovation Program (Xinmiao Talent Program, No. 2025R404AB061).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vardi, M.Y. Will MOOCs destroy academia? Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wei, M.; Feng, J.; Yu, F.; Li, Q.; Zou, R. Progressive knowledge tracing: Modeling learning process from abstract to concrete. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, J.; Cai, T.; Yang, S.; Yang, T.; Liu, C. A survey on deep learning based knowledge tracing. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 258, 110036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, G.; Wang, Q.; Nunes, B. Knowledge tracing: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Boyle, C.F.; Corbett, A.T.; Lewis, M.W. Cognitive modeling and intelligent tutoring. Artif. Intell. 1990, 42, 7–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, M. Probabilistic student models: Bayesian belief networks and knowledge space theory. In International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 491–498. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, A.T.; Anderson, J.R. Knowledge tracing: Modeling the acquisition of procedural knowledge. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 1994, 4, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piech, C.; Bassen, J.; Huang, J.; Ganguli, S.; Sahami, M.; Guibas, L.J.; Sohl-Dickstein, J. Deep knowledge tracing. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, E.; Huang, Z.; Huang, W.; Yin, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, S. Learning process-consistent knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Virtual Event, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 1452–1460. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Su, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, E. Assessing student’s dynamic knowledge state by exploring the question difficulty effect. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, X.; King, I.; Yeung, D.Y. Dynamic key-value memory networks for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 765–774. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrahman, G.; Wang, Q. Knowledge tracing with sequential key-value memory networks. In Proceedings of the 42nd International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Paris, France, 21–25 July 2019; pp. 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrahman, G.; Wang, Q. Deep graph memory networks for forgetting-robust knowledge tracing. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 7844–7855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, Y.; Cho, J.; Baek, J.; Kim, B.; Cha, Y.; Shin, D.; Bae, C.; Heo, J. Towards an appropriate query, key, and value computation for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, Virtual Event, USA, 12–14 August 2020; pp. 341–344. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Heffernan, N.; Lan, A.S. Context-aware attentive knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Virtual Event, CA, USA, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 2330–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, H.; Iwasawa, Y.; Matsuo, Y. Graph-based knowledge tracing: Modeling student proficiency using graph neural network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence, Thessaloniki, Greece, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Shen, J.; Qu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Y. GIKT: A graph-based interaction model for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Virtual, 14–18 September 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ma, H.; Ma, Y.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, C.; Ko, J. DGEKT: A dual graph ensemble learning method for knowledge tracing. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2024, 42, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Peng, L.; Wang, P.; Ye, J.; Sun, L.; Du, B. DyGKT: Dynamic graph learning for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 409–420. [Google Scholar]

- Cen, H.; Koedinger, K.; Junker, B. Learning factors analysis—A general method for cognitive model evaluation and improvement. In International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 164–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlik, P.I., Jr.; Cen, H.; Koedinger, K.R. Performance Factors Analysis—A New Alternative to Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the 2009 Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education: Building Learning Systems That Care: From Knowledge Representation to Affective Modelling, Brighton, UK, 6–10 July 2009; pp. 531–538. [Google Scholar]

- Vie, J.J.; Kashima, H. Knowledge tracing machines: Factorization machines for knowledge tracing. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2019, 33, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, C.K.; Yeung, D.Y. Addressing two problems in deep knowledge tracing via prediction-consistent regularization. In Proceedings of the 5th Annual ACM Conference on Learning at Scale, London, UK, 26–28 June 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nagatani, K.; Zhang, Q.; Sato, M.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, F.; Ohkuma, T. Augmenting knowledge tracing by considering forgetting behavior. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on World Wide Web, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 3101–3107. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Huang, Z.; Gao, J.; Shang, M.; Shu, M.; Sun, J. Enhancing knowledge tracing via adversarial training. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Virtual Event, China, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 367–375. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Shen, S.; Liu, Q.; Chen, E.; Wu, J.; Wang, S. Learning behavior-oriented knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Long Beach, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 2789–2800. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Tang, J.; Wang, T. MAN: Memory-augmented Attentive Networks for Deep Learning-based Knowledge Tracing. ACM Trans. Inf. Systems. 2023, 42, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Karypis, G. A self-attentive model for knowledge tracing. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, Montréal, QC, Canada, 2–5 July 2019; pp. 384–389. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Y.; Liu, F.; Shi, R.; Yuan, H.; Chen, R.; Peng, T.; Wu, W. ELAKT: Enhancing Locality for Attentive Knowledge Tracing. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2024, 42, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Luo, W.; Weng, J. Towards robust knowledge tracing models via k-sparse attention. In Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–27 July 2023; pp. 2441–2445. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Jia, J.; Wen, C.; Li, D.; Li, M. Multi-topology contrastive graph representation learning. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2026, 69, 122102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chang, Y.; Li, M.; Qin, A.; Zhang, X. AutoSGRL: Automated framework construction for self-supervised graph representation learning. Neural Netw. 2025, 194, 108119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Li, M.; Feng, H.; Zhuang, X. Deeper insights into deep graph convolutional networks: Stability and generalization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.; Liu, Q.; Huang, W.; Hunag, Z.; Chen, E.; Liu, C.; Ma, H.; Wang, S. Structure-based knowledge tracing: An influence propagation view. In Proceedings of the 20th IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Sorrento, Italy, 17–20 November 2020; pp. 541–550. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Tong, S.; Han, W.; Liu, Q. Introducing Problem Schema with Hierarchical Exercise Graph for Knowledge Tracing. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022; pp. 405–415. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, J.X. Exploring long-and short-term knowledge state graph representations with adaptive fusion for knowledge tracing. Inf. Process. Manag. 2025, 62, 104074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Wang, W.; Tan, W.; Du, L.; Jin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yin, H. HiTSKT: A hierarchical transformer model for session-aware knowledge tracing. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 284, 111300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Yu, F.; Liu, Y.; Liang, R.; Wan, Q.; Yang, T.; Shi, M.; Sun, J. Enhancing knowledge tracing with question-based contrastive learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 325, 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Dai, L.; Huang, Z.; Shen, S.; Wang, F.; Liu, Q.; Chen, E.; Li, X. Tracing knowledge instead of patterns: Stable knowledge tracing with diagnostic transformer. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM Web Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 855–864. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Guan, Q.; He, Y.; He, Z.; Fang, L.; Luo, W. Knowledge tracing model with learning and forgetting behavior. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–21 October 2022; pp. 3863–3867. [Google Scholar]

- Long, T.; Qin, J.; Shen, J.; Zhang, W.; Xia, W.; Tang, R.; He, X.; Yu, Y. Improving knowledge tracing with collaborative information. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Virtual Event, AZ, USA, 21–25 February 2022; pp. 599–607. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Li, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Y.; Guan, Z. Jkt: A joint graph convolutional network based deep knowledge tracing. Inf. Sci. 2021, 580, 510–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, C.; Pan, F.; Qian, W.; Zhao, H. No length left behind: Enhancing knowledge tracing for modeling sequences of excessive or insufficient lengths. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Birmingham, UK, 21–25 October 2023; pp. 3226–3235. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Subplot (I) shows a sequence of six interaction records (–) associated with three knowledge concepts (–). Knowledge tracing predicts the student’s responses and models the evolution of concept-level knowledge states, visualized as a series of radar charts. Subplot (II) illustrates the learning process, where interaction denotes the answering and feedback, accumulation represents knowledge gain after each interaction, and transfer propagates the gained knowledge to related concepts according to inter-concept relationships.

Figure 1.

Subplot (I) shows a sequence of six interaction records (–) associated with three knowledge concepts (–). Knowledge tracing predicts the student’s responses and models the evolution of concept-level knowledge states, visualized as a series of radar charts. Subplot (II) illustrates the learning process, where interaction denotes the answering and feedback, accumulation represents knowledge gain after each interaction, and transfer propagates the gained knowledge to related concepts according to inter-concept relationships.

Figure 2.

The overall architecture of the proposed DyGAS model, consisting of (I) a sequential knowledge modeling module, (II) a structural knowledge modeling module (including dynamic and static knowledge modeling), and (III) a prediction and training module.

Figure 2.

The overall architecture of the proposed DyGAS model, consisting of (I) a sequential knowledge modeling module, (II) a structural knowledge modeling module (including dynamic and static knowledge modeling), and (III) a prediction and training module.

Figure 3.

Visualization of a student’s knowledge state evolution over a sequence of 15 exercises – across three knowledge concepts – on the ASSIST2009. Each cell represents the predicted probability of an exercise. The DyGAS jointly leverages sequential and structural knowledge modeling, while the DyGAS-AL variant uses only sequential modeling.

Figure 3.

Visualization of a student’s knowledge state evolution over a sequence of 15 exercises – across three knowledge concepts – on the ASSIST2009. Each cell represents the predicted probability of an exercise. The DyGAS jointly leverages sequential and structural knowledge modeling, while the DyGAS-AL variant uses only sequential modeling.

Figure 4.

The evolution of knowledge adjacency (T = 0 and T = 15). As learning progresses, the similarity among , and increases.

Figure 4.

The evolution of knowledge adjacency (T = 0 and T = 15). As learning progresses, the similarity among , and increases.

Figure 5.

Impact of d on performance.

Figure 5.

Impact of d on performance.

Figure 6.

Impact of on performance.

Figure 6.

Impact of on performance.

Figure 7.

Training time per epoch in minutes for various knowledge tracing models on ASSIST2009. DKT represents a sequential model, and DKVMN is memory-based. SAKT and AKT are attention-based. GKT, GIKT, and DGEKT are graph-based. DyGAS corresponds to the proposed model, and DyGAS-AL is the variant without the graph-based structural modeling module.

Figure 7.

Training time per epoch in minutes for various knowledge tracing models on ASSIST2009. DKT represents a sequential model, and DKVMN is memory-based. SAKT and AKT are attention-based. GKT, GIKT, and DGEKT are graph-based. DyGAS corresponds to the proposed model, and DyGAS-AL is the variant without the graph-based structural modeling module.

Figure 8.

t-SNE visualization of exercise embeddings before and after training on ASSIST2009. Nodes of different colors represent exercises associated with different knowledge concepts.

Figure 8.

t-SNE visualization of exercise embeddings before and after training on ASSIST2009. Nodes of different colors represent exercises associated with different knowledge concepts.

Table 1.

Summary of key notations and description.

Table 1.

Summary of key notations and description.

| Symbol | Description |

|---|

| N | Total number of exercises |

| M | Total number of knowledge concepts |

| The knowledge set related to the t-th exercise |

| The t-th exercise attempted by a student |

| Correctness of the response to (1=correct, 0=incorrect) |

| Interaction embedding of the t-th exercise |

| d | Embedding dimension |

| Exercise embedding matrix of size |

| Dynamic knowledge embedding matrix at time t of size |

| Static knowledge embedding matrix of size |

| Exercise–concept association matrix of size |

| Interaction gain vector at time t |

| Absorption gate controlling knowledge gain incorporation |

| Gate controlling retention of previous knowledge |

| Dynamic knowledge graph at time t |

| Adjacency matrix of the knowledge graph, shape |

| Edge weight between concepts i and j at time t |

| Dynamic exercise-specific knowledge state vector |

| Static exercise-specific knowledge state vector |

| Predicted probability that the student answers correctly |

| Binary cross-entropy losses for main and auxiliary predictions |

| Weighting coefficients for auxiliary losses |

Table 3.

Performance comparison between DyGAS and baselines. “-’’ denotes unavailable results. Each model is run five times and the mean metrics are reported (variance < 0.001). ↑ means higher is better; ↓ means lower is better. The best result is in bold and the second-best is underlined.

Table 3.

Performance comparison between DyGAS and baselines. “-’’ denotes unavailable results. Each model is run five times and the mean metrics are reported (variance < 0.001). ↑ means higher is better; ↓ means lower is better. The best result is in bold and the second-best is underlined.

| Method | ASSIST2009 | ASSIST2017 | Junyi |

|---|

| |

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RSME ↓

|

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RSME ↓

|

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RSME ↓

|

|---|

| BKT [7] | 0.6571 | 0.6209 | 0.4897 | 0.6365 | 0.5983 | 0.4993 | 0.7100 | 0.6819 | 0.4683 |

| DKT [8] | 0.7431 | 0.7127 | 0.4372 | 0.7295 | 0.6940 | 0.4454 | 0.7586 | 0.8326 | 0.3536 |

| DKVMN [11] | 0.7401 | 0.7038 | 0.4416 | 0.7511 | 0.7043 | 0.4379 | 0.7565 | 0.8324 | 0.3544 |

| SAKT [28] | 0.7111 | 0.6885 | 0.4545 | 0.6605 | 0.6694 | 0.4626 | 0.7590 | 0.8323 | 0.3544 |

| AKT [15] | 0.7766 | 0.7289 | 0.4273 | 0.7548 | 0.7108 | 0.4308 | 0.7593 | 0.8325 | 0.3538 |

| HiTSKT [37] | 0.7766 | 0.7539 | 0.4112 | 0.7566 | 0.7011 | 0.4453 | - | - | - |

| GKT [16] | 0.7231 | 0.7091 | 0.4575 | 0.7566 | 0.7132 | 0.4324 | 0.7589 | 0.8331 | 0.3535 |

| GIKT [17] | 0.7896 | 0.7315 | 0.4221 | 0.7623 | 0.6985 | 0.4325 | - | - | - |

| DGEKT [18] | 0.7656 | 0.7599 | 0.4198 | 0.7755 | 0.7208 | 0.5283 | - | - | - |

| L-SKSKT [36] | 0.8448 | 0.8159 | 0.3846 | - | - | - | 0.7769 | 0.8291 | 0.3499 |

| DyGAS | 0.8837 | 0.8186 | 0.3521 | 0.7828 | 0.7294 | 0.4221 | 0.7771 | 0.8374 | 0.3469 |

| % Improve | 4.61% | 0.33% | −8.45% | 0.94% | 1.19% | −2.02% | 0.03% | 0.52% | −0.86% |

Table 4.

Ablation Study of different variants. Variants include: AU, removing the auxiliary loss used to supervise dynamic and static knowledge modeling; DM, removing dynamic knowledge modeling; SM, removing static knowledge modeling that provides stable embeddings for each concept; AL, removing all structure-related components, including dynamic and static knowledge modeling and auxiliary supervision; and FG, removing the forgetting gate that selectively retains or discards historical knowledge. ↑ means higher is better; ↓ means lower is better. The best result is in bold.

Table 4.

Ablation Study of different variants. Variants include: AU, removing the auxiliary loss used to supervise dynamic and static knowledge modeling; DM, removing dynamic knowledge modeling; SM, removing static knowledge modeling that provides stable embeddings for each concept; AL, removing all structure-related components, including dynamic and static knowledge modeling and auxiliary supervision; and FG, removing the forgetting gate that selectively retains or discards historical knowledge. ↑ means higher is better; ↓ means lower is better. The best result is in bold.

| Variants | ASSIST2009 | ASSIST2017 | Junyi |

|---|

| |

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RSME ↓

|

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RSME ↓

|

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RSME ↓

|

|---|

| AU | 0.8802 | 0.8166 | 0.3547 | 0.7825 | 0.7291 | 0.4423 | 0.7745 | 0.8369 | 0.3473 |

| DM | 0.8820 | 0.8165 | 0.3541 | 0.7809 | 0.7281 | 0.4233 | 0.7740 | 0.8365 | 0.3476 |

| SM | 0.8797 | 0.8146 | 0.3553 | 0.7816 | 0.7286 | 0.4226 | 0.7748 | 0.8367 | 0.3474 |

| AL | 0.8767 | 0.8135 | 0.3556 | 0.7806 | 0.7281 | 0.4234 | 0.7727 | 0.8361 | 0.3481 |

| FG | 0.8659 | 0.8049 | 0.3667 | 0.7648 | 0.7164 | 0.4302 | 0.7603 | 0.8341 | 0.3513 |

| DyGAS | 0.8837 | 0.8186 | 0.3521 | 0.7828 | 0.7294 | 0.4221 | 0.7771 | 0.8374 | 0.3469 |

Table 5.

Impact of and on Performance. ↑ means higher is better; ↓ means lower is better. The best result is in bold.

Table 5.

Impact of and on Performance. ↑ means higher is better; ↓ means lower is better. The best result is in bold.

| Param | Value | ASSIST2009 | ASSIST2017 | Junyi |

|---|

| | |

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RMSE ↓

|

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RMSE ↓

|

AUC ↑

|

ACC ↑

|

RMSE ↓

|

|---|

| 0.0 | 0.8764 | 0.8132 | 0.3590 | 0.7826 | 0.7288 | 0.4223 | 0.7748 | 0.8370 | 0.3473 |

| 0.2 | 0.8744 | 0.8114 | 0.3606 | 0.7824 | 0.7290 | 0.4222 | 0.7750 | 0.8371 | 0.3471 |

| 0.4 | 0.8742 | 0.8120 | 0.3604 | 0.7822 | 0.7282 | 0.4227 | 0.7752 | 0.8371 | 0.3473 |

| 0.6 | 0.8748 | 0.8121 | 0.3602 | 0.7823 | 0.7290 | 0.4225 | 0.7753 | 0.8370 | 0.3472 |

| 0.8 | 0.8740 | 0.8126 | 0.3601 | 0.7823 | 0.7286 | 0.4223 | 0.7757 | 0.8374 | 0.3469 |

| 1.0 | 0.8753 | 0.8138 | 0.3596 | 0.7828 | 0.7294 | 0.4221 | 0.7771 | 0.8374 | 0.3469 |

| 0.0 | 0.8703 | 0.8095 | 0.3632 | 0.7823 | 0.7288 | 0.4226 | 0.7762 | 0.8373 | 0.3469 |

| 0.2 | 0.8711 | 0.8104 | 0.3627 | 0.7826 | 0.7296 | 0.4223 | 0.7763 | 0.8374 | 0.3468 |

| 0.4 | 0.8728 | 0.8116 | 0.3612 | 0.7828 | 0.7292 | 0.4222 | 0.7761 | 0.8374 | 0.3468 |

| 0.6 | 0.8754 | 0.8134 | 0.3591 | 0.7831 | 0.7296 | 0.4220 | 0.7759 | 0.8373 | 0.3469 |

| 0.8 | 0.8746 | 0.8121 | 0.3605 | 0.7835 | 0.7301 | 0.4218 | 0.7756 | 0.8372 | 0.347 |

| 1.0 | 0.8753 | 0.8138 | 0.3596 | 0.7828 | 0.7294 | 0.4221 | 0.7771 | 0.8374 | 0.3469 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).