Coupled Water–Nitrogen Transport and Multivariate Prediction Models for Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

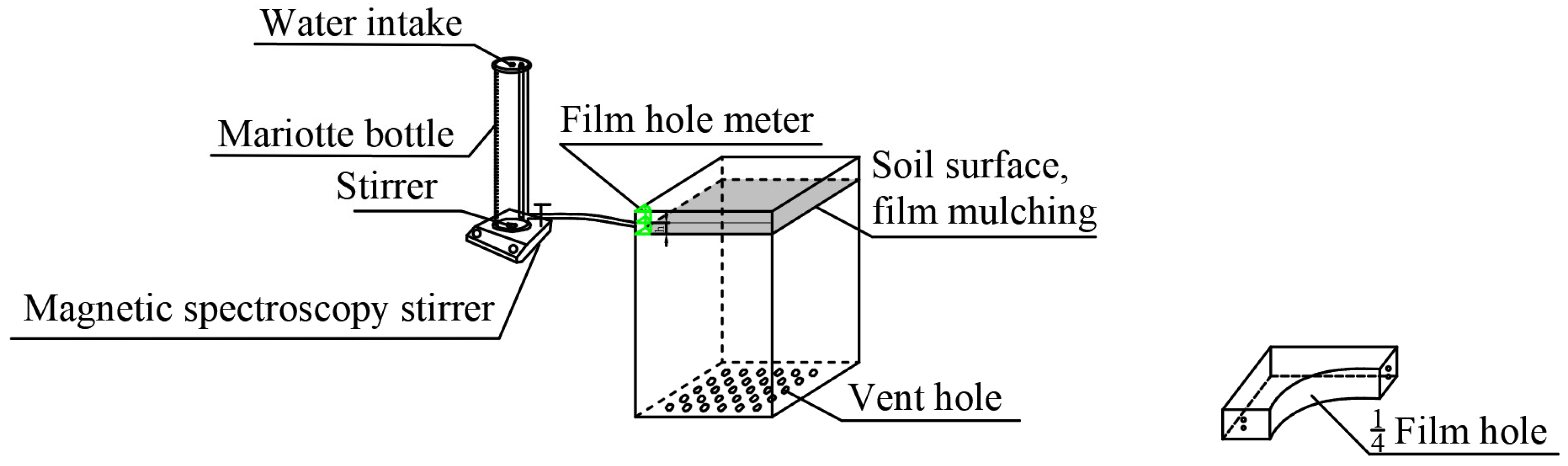

2.2. Experimental Methods and Apparatuses

2.3. Experimental Design and Measured Parameters

2.3.1. Experimental Design

2.3.2. Measured Parameters and Methods

- (1)

- Wetting front migration distance and cumulative infiltration volume: To accurately capture the initial rapid infiltration phase while minimizing disturbance in later stages, measurements were taken at progressively longer intervals. Specifically, the wetting front migration distance and readings from the Mariotte bottle were recorded at the following frequencies: every 2 min from 0 to 9 min; every 5 min from 10 to 30 min; every 15 min from 31 to 60 min; and every 30 min from 61 to 600 min.

- (2)

- Soil Water Content: Upon completion of each infiltration experiment, the wetted soil volume was immediately sampled by layer using a soil auger. To ensure representative sampling, samples were collected at 3 cm intervals in both horizontal and vertical directions. The samples were promptly sealed to prevent moisture loss and subsequently analyzed for water content using the oven-drying method.

- (3)

- Soil Ammonium Nitrogen: The soil samples collected from each grid point were divided into two portions. One portion was used for water content determination, while the other was immediately extracted for nitrogen analysis. Fresh soil samples (5.00 g) were extracted with 50 mL of 2 mol/L KCl solution. After shaking for 1 h and filtering, the concentration of ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) in the extracts was measured using a fully automated discrete chemical analyzer (SMARTCHEM 450, AMSGroup, Bergamo, Italy), following the standard protocol (HJ 535-2009/ISO 11732 [20,21]).

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

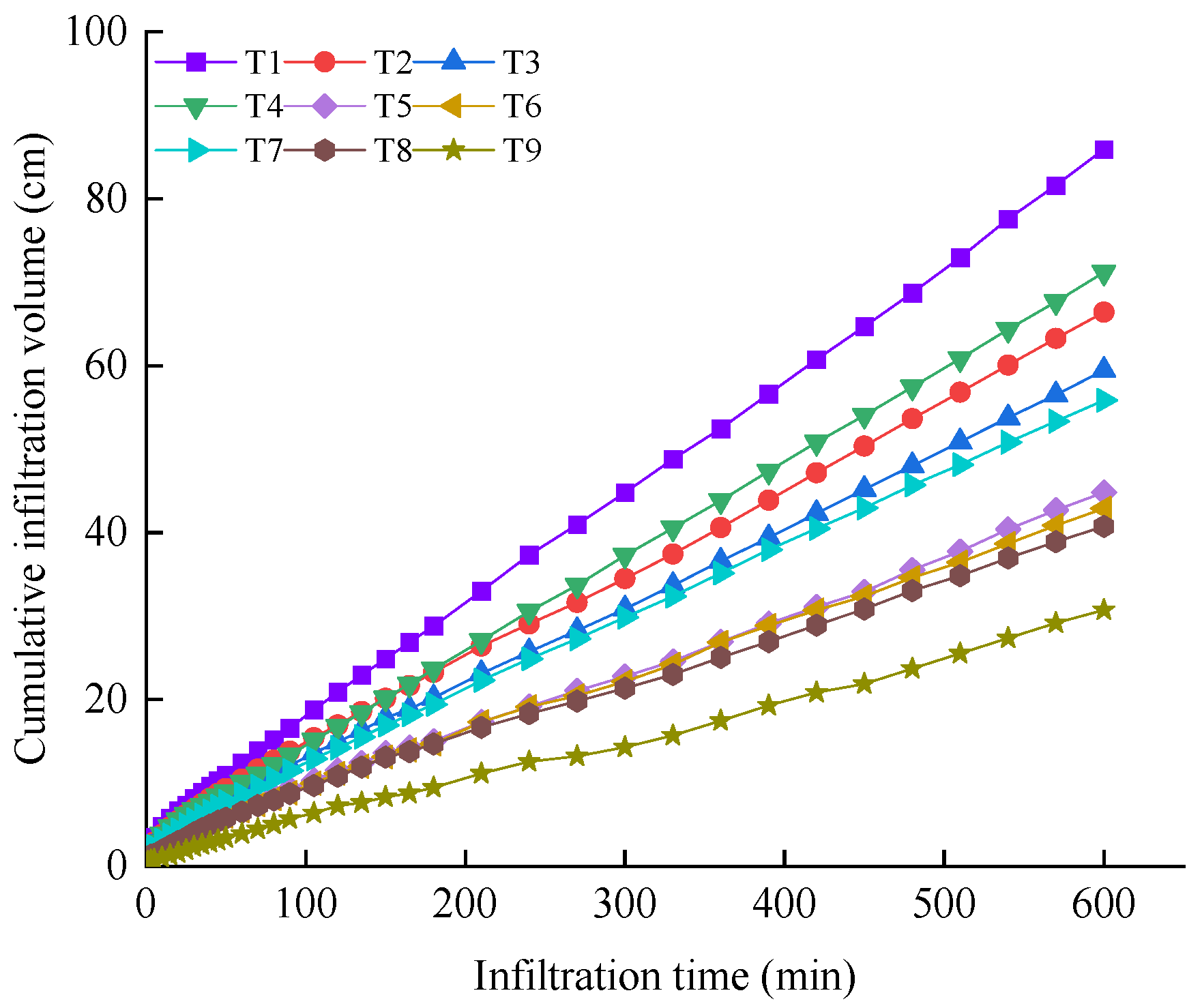

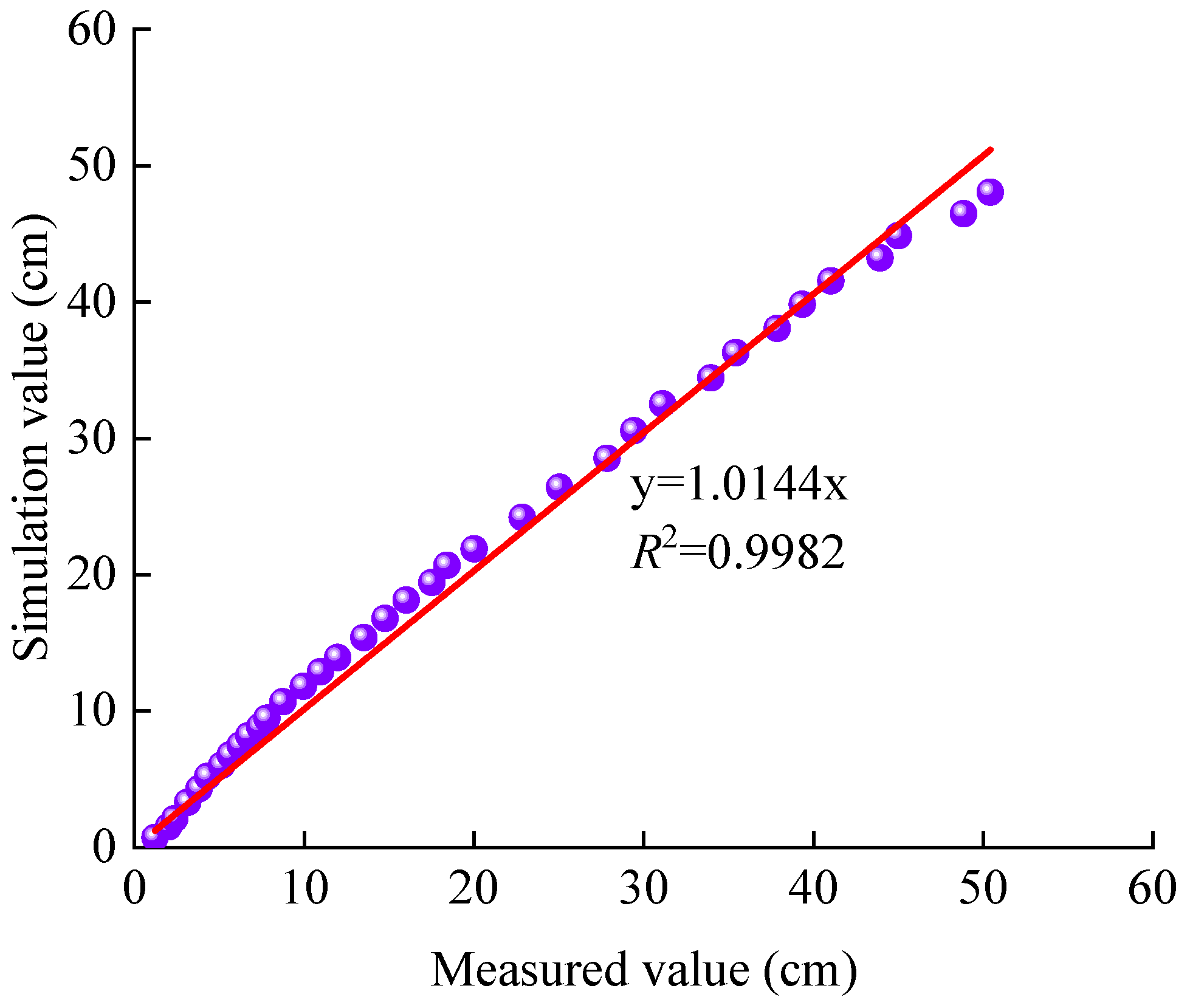

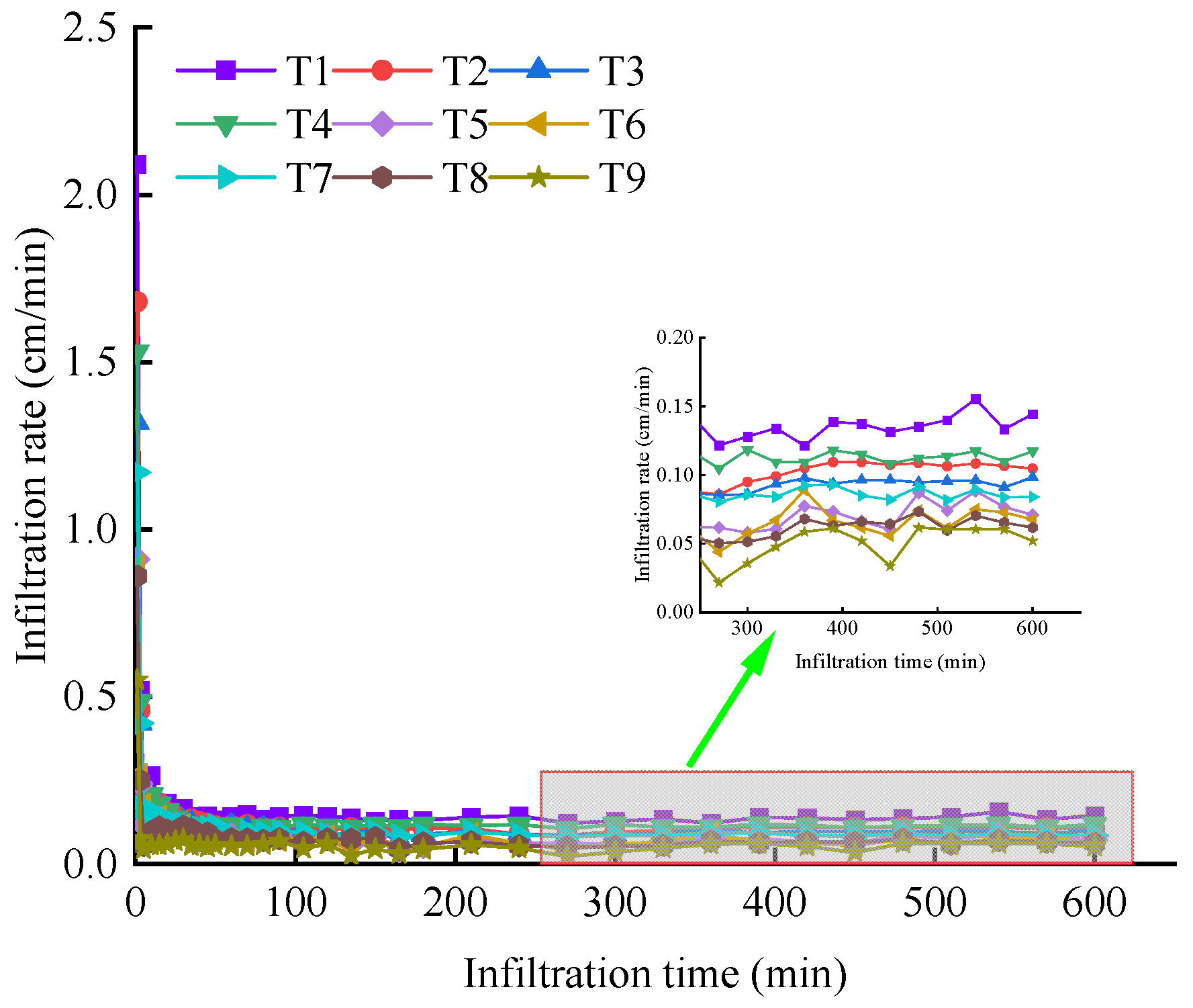

3.1. Cumulative Infiltration Volume and Infiltration Rate

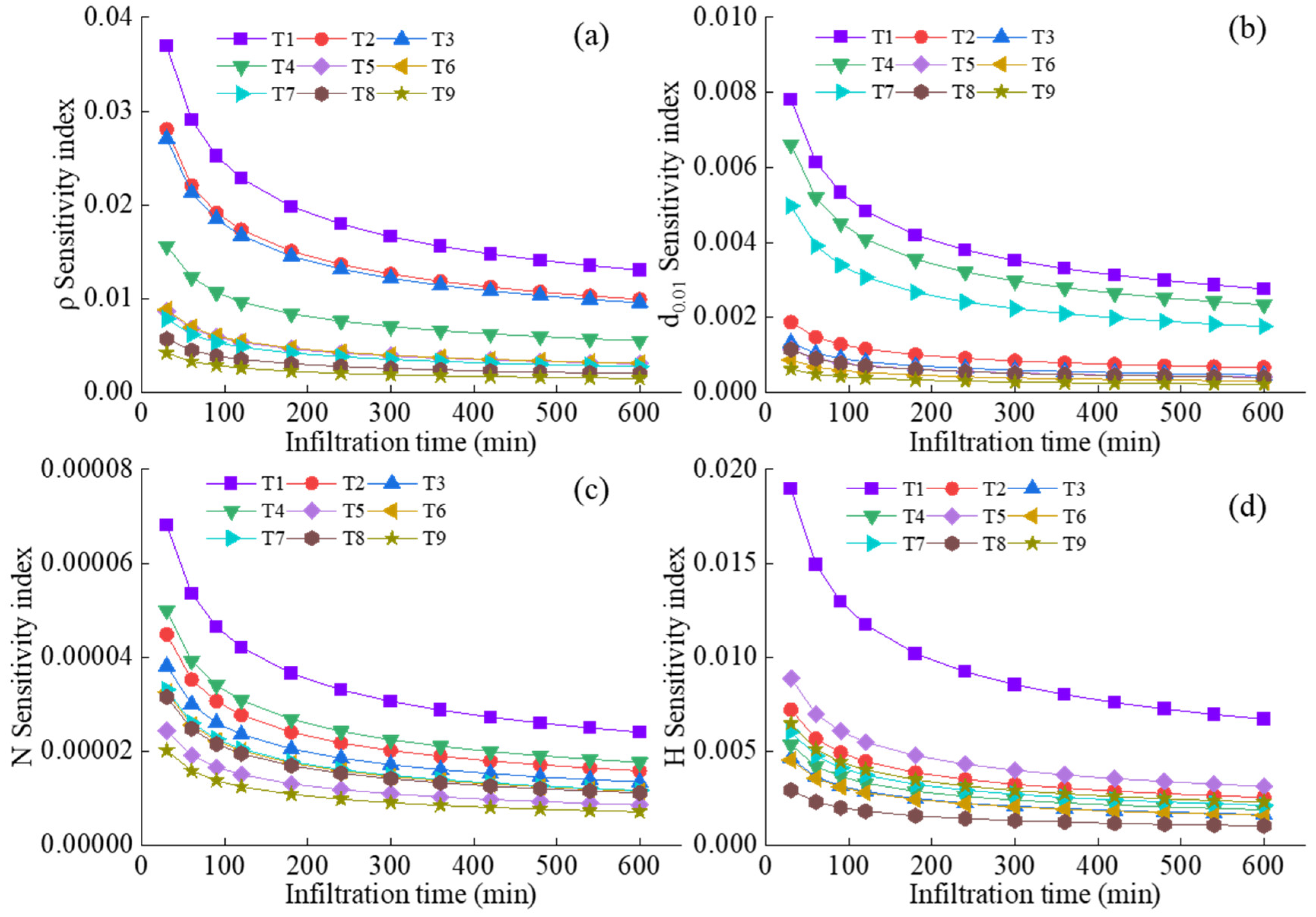

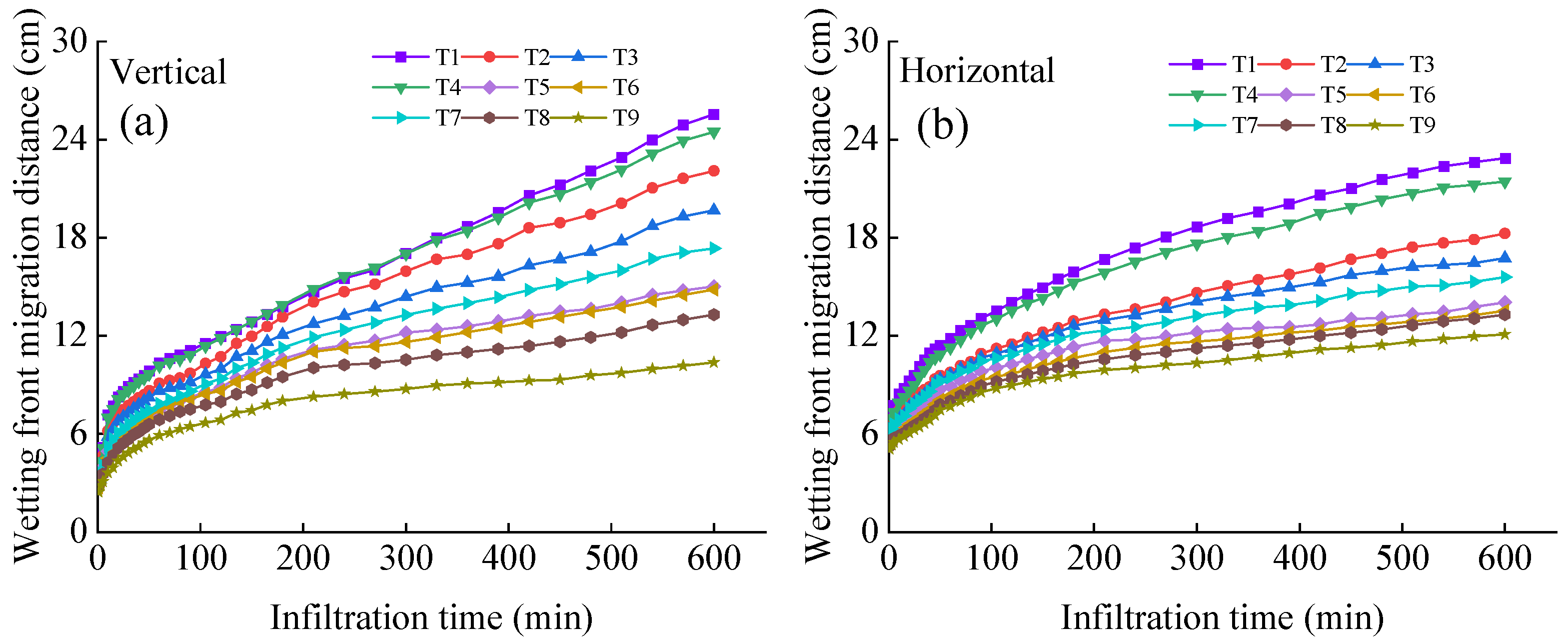

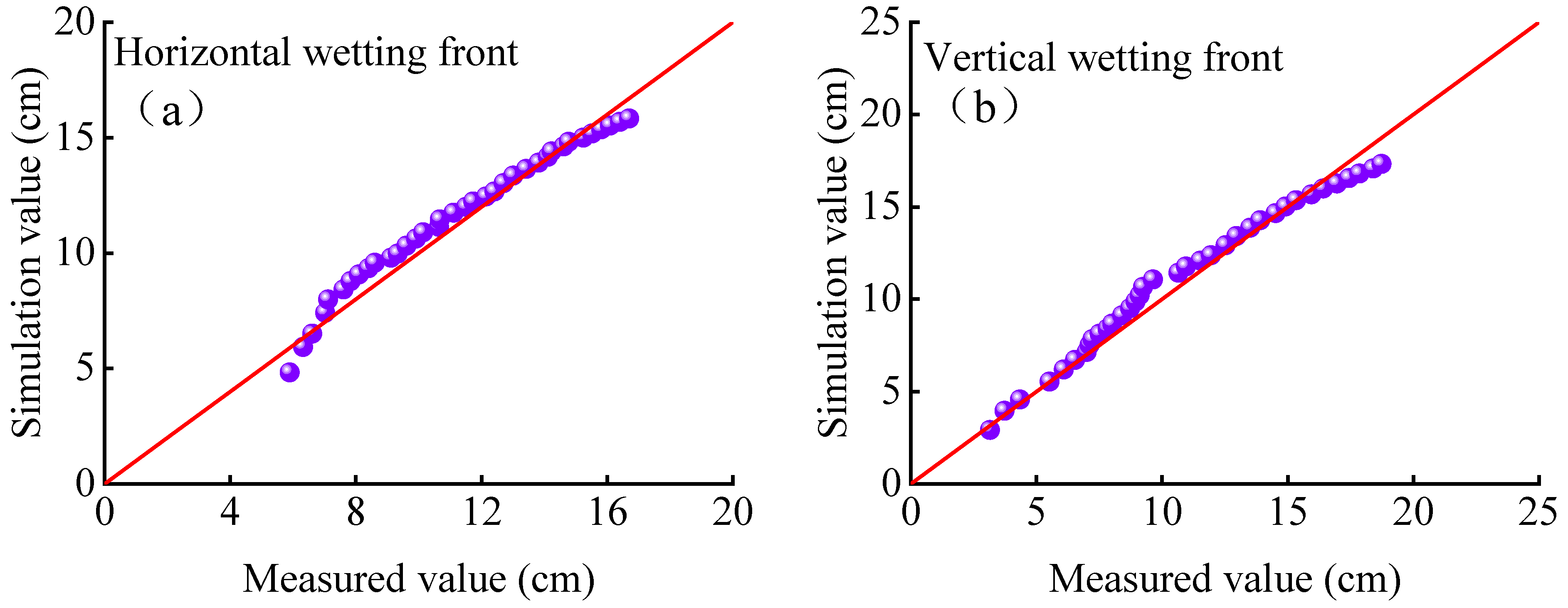

3.2. Wetting Front Migration Characteristics and Model Establishment

3.3. Water and Nitrogen Distribution in the Wetted Volume

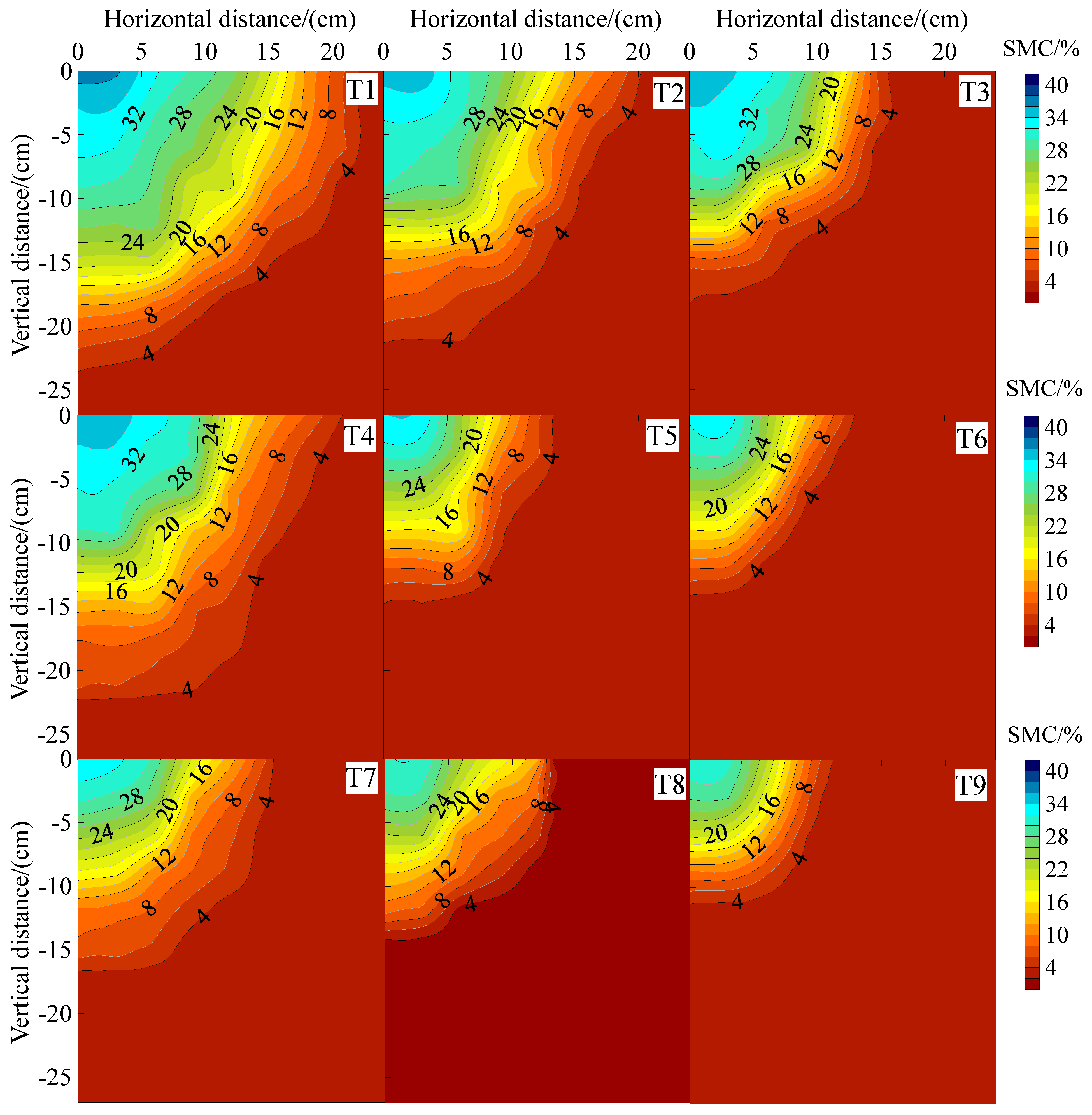

3.3.1. Soil Water Content Distribution

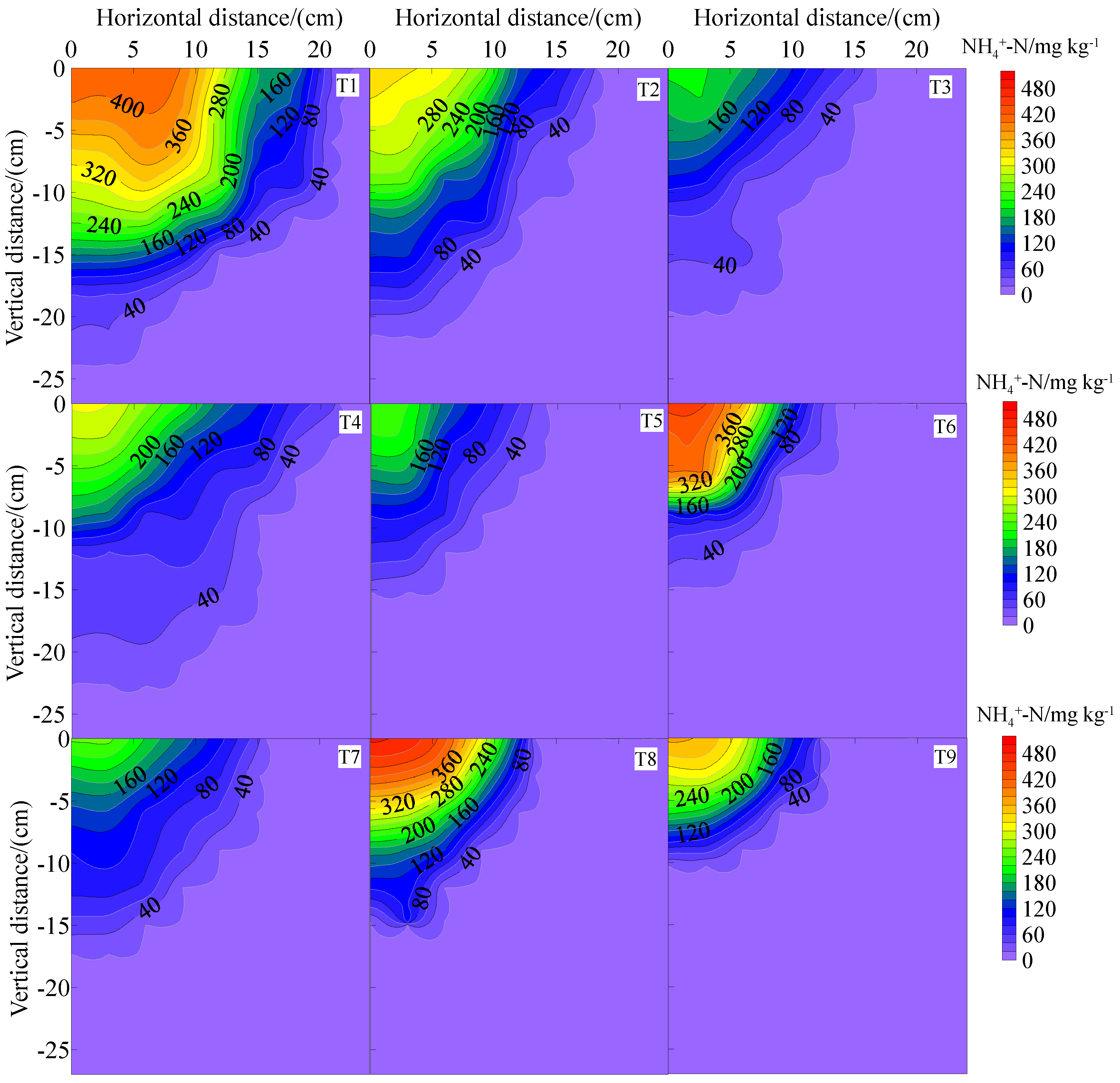

3.3.2. Ammonium Nitrogen Distribution

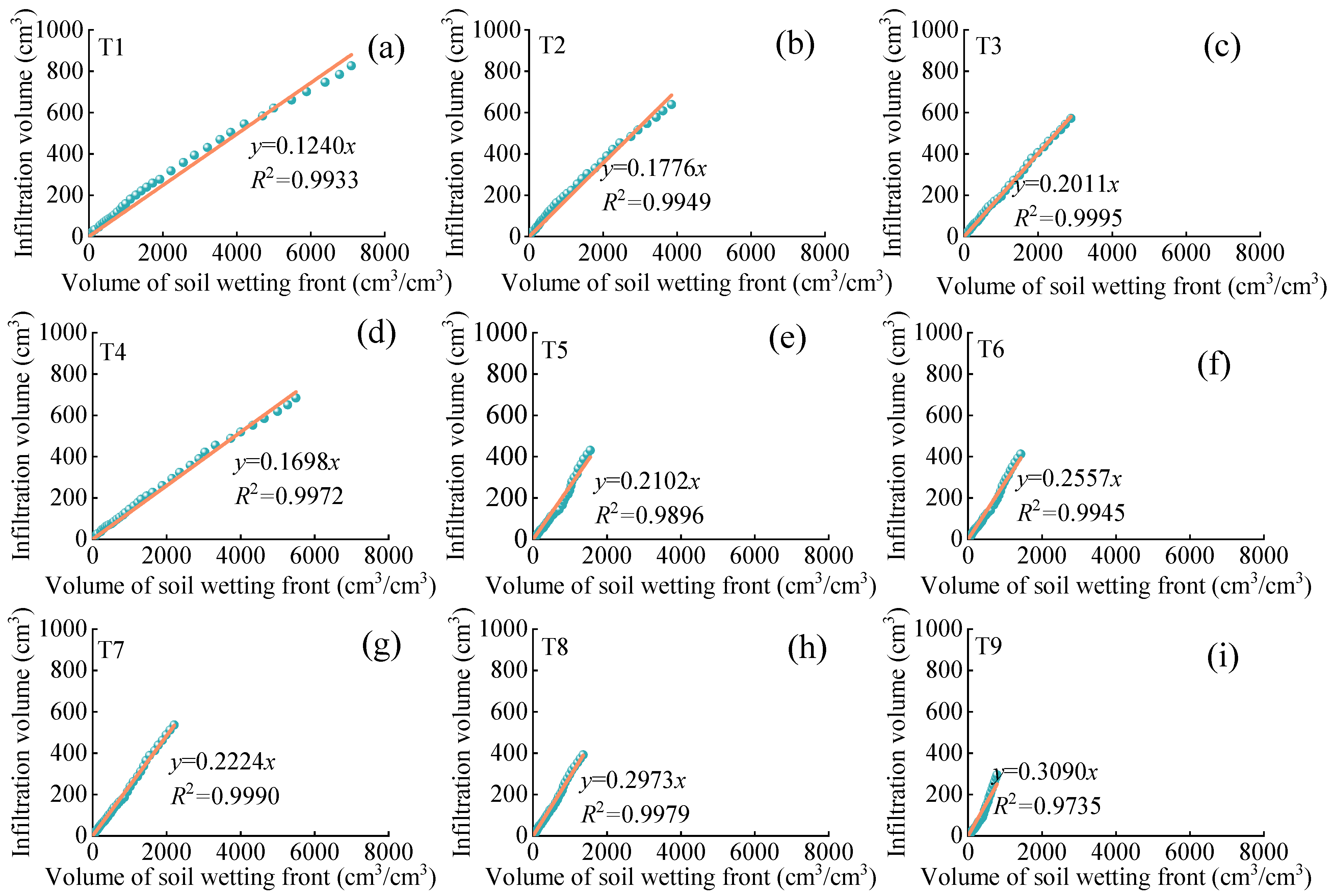

3.4. Dynamic Changes in the Average Volumetric Water Content Increment of the Wetted Soil

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Multiple Factors on the Infiltration Characteristics of Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation

4.2. Effects of Multiple Factors on Water and Nitrogen Distribution in Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation

4.3. Influence of Multiple Factors on the Increase in Soil Water Content Within the Wetted Volume

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, L.N.; Zhao, Z.L.; Li, J.; Wang, H.M.; Guo, G.M.; Wu, W.B. Effects of muddy water irrigation with different sediment particle sizes and sediment concentrations on soil microbial communities in the Yellow River Basin of China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 270, 107750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Fei, L.J.; Peng, Y.L.; Wang, A.X.; Liu, W.B.; Xu, Z.; Fan, Q.W. Influences of biochar addition on soil water and salt transport of infiltration with muddy water in saline-alkali soil. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2025, 41, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.L.; Fei, L.J.; Xue, R.M.; Shen, F.Y.; Zhen, R.Q.; Wang, Q. Effect of Muddy Water Characteristics on Infiltration Laws and Stratum Compactum Soil Particle Composition under Film Hole Irrigation. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.J.; Peng, Y.L.; Yang, Z.; Shen, F.Y.; Zheng, R.Q.; Wang, Q. Characteristics of Soil Water and Nitrogen Transport in Fertilized Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation with Variable Environmental Temperature. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24, 7980–7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, H.R.; Bi, Z.Z.; Xu, Z.H. Characteristics of Vegetation Resistance Variation in Muddy Water Flows. Water 2023, 15, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.N.; Zhao, Z.L.; Guo, G.M.; Li, J.; Wu, W.B.; Zhang, F.X.; Zhang, X. Effects of muddy water irrigation with different sediment gradations on nitrogen transformation in agricultural soil of Yellow River Basin. Water Sci. Eng. 2023, 15, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Zhang, X.P.; Li, R.; Chen, L.L.; Lin, P.F. Did streamflow or suspended sediment concentration changes reduce sediment load in the middle reaches of the Yellow River? J. Hydrol. 2017, 546, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.R.; Fei, L.J.; Jin, S.J.; Fu, Y.L.; Zhong, Y. Effects of Silt Content and Clay and Sand Grade on Freedom Infiltration Characteristics of Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2018, 32, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.H.; Fei, L.J.; Chen, L.; Hao, K. Effects of sediment concentration of muddy water on water and nitrogen transport characteristics under film hole irrigation with fertilizer infiltration. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L.J.; Wang, J.H. Effect of Clay and Sand Grades on Single-line Interference Infiltration Characteristics of Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2016, 47, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.H.; Fei, L.J.; Liu, D.Y. Distribution of water and nitrogen in soil infiltration by fertilizer film hole irrigation under formation of soil dense layer. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2023, 41, 709–715. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.X.; Fei, L.J.; Jiang, R.R.; Zhong, Y. Effect of Fertilizer Concentration on Water and Nitrogen Migration in Multi-point Source Infiltration of Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2019, 33, 156–161. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, Y.F.; Wang, K.Q.; Zhang, L.J.; Fei, L.J. Influence of fertilizer solution concentration on transfer and transform of soil moisture and nitrogen under intersection film hole irrigation. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2014, 32, 541–546. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 19077-2016; Particle Size Analysis—Laser Diffraction Methods. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Zhong, Y.; Fei, L.J.; Zhu, S.J.; He, J.; Kang, S.X. Effects of muddy water characteristics on soil particle composition and fractal characteristics under film hole irrigation. Soil Fertil. Sci. China 2023, 1, 184–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.X.; Fei, L.J.; Zhong, Y.; Zhao, P.H.; Yang, Z.; Fan, Q.W. Effects of muddy water infiltration on the hydraulic conductivity of soils by multiple factors. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2023, 39, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.X.; Fei, L.J.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, P.H.; Wang, Q.; Fan, Q.W.; Liu, L.H. Effects of Muddy Water Infiltration on the Hydraulic Conductivity of Soils. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.H.; Fei, L.J.; Chen, L.; Hao, K.; Zhang, Q.J. Effects of initial soil moisture content on soil water and nitrogen transport under muddy water film hole infiltration. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 11901-1989; Water Quality—Determination of Suspended Substance—Gravimetric Method. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1989.

- HJ 535-2009; Water Quality—Determination of Ammonia Nitrogen—Nessler Reagent Spectrophotometry. Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- ISO 11732; Water Quality—Determination of Ammonium Nitrogen—Method by flow Analysis (CFA and FIA) and Spectrometric Detection. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Zhong, Y.; Fei, L.G.; Zhu, S.G.; Kang, S.X.; Liu, L.H.; Hao, K.; Jie, F.L. Infiltration Characteristics of Muddy Water Film-Hole Irrigation and Formation Characteristics of Dense Layers. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 36, 238–246+254. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.X.; Fei, L.J.; Xue, R.M.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, P.H.; Fan, Q.W. Multifactor analysis of the infiltration characteristics of film hole irrigation under muddy water conditions. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.L.; Fei, L.J.; Jie, F.L.; Hao, K.; Liu, L.H.; Shen, F.; Fan, Q.W. Effects of Bio-Organic Fertilizer on Soil Infiltration, Water Distribution, and Leaching Loss under Muddy Water Irrigation Conditions. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.T.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, G.C.; He, T.; Gu, Y. Experimental study on influences of seepage of muddy water on porosity and permeability of coarse-grained soil columns. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 47, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Zai, S.M.; Nie, M.M.; Wu, F.; Huang, J.; Gao, X.J.; Liu, W.Y. Impact of Different Water Supply Modes on the Hydraulic Reliability of Large-Scale Irrigation Pipeline Network. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, W.N.; Hu, X.T.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, F.L. Effect of fertilizer solution concentrations on filter clogging in drip fertigation systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 250, 106829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.S.; Yang, X.Q. Determining injection strategies of phosphorus-coupled nitrogen fertigation based on clogging control of drip emitters with saline water application. Irrig. Drain. 2021, 70, 1010–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.J.; Nie, W.B.; Ma, Y.P.; Li, Y.C.; Ma, X.Y.; Zhu, H.Y. Effects of urea solution concentration on soil hydraulic properties and water infiltration capacity. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 898, 165471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostiakov, A.N. On the dynamics of the coefficient of water-percolation in soils and on the necessity of studying it from a dynamic point of view for purposes of amelioration. In Transactions of the 6th Commission of International Society of Soil Science; International Society of Soil Science: Vienna, Austria, 1932; pp. 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.D.; Nie, W.B.; Feng, Z.J.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.Y. Effects of Fertilization Timing on Soil Water and Nitrogen Transport and Transformation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 36, 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Y.Y. Effect of integration of water and fertilizer on soil water-nitrogen transport characteristics in Bubbled-root Irrigation. Irrig. Sci. 2023, 41, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Chen, X.F.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Guo, X. Evaluating soil water and nitrogen transport, nitrate leaching and soil nitrogen concentration uniformity under sprinkler irrigation and fertigation using numerical simulation. J. Hydrol. 2025, 647, 132345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Real, R.; Muñoz, I.; Gutierrez-Cánovas, C.; Granados, V.; Lopez-Laseras, P.; Menéndez, M. Subsurface zones in intermittent streams are hotspots of microbial decomposition during the non-flow period. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 135485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.J.; Wu, F.S.; Li, L.; Shang, R.H.; Li, D.D.; Xu, L.N.; Cui, J.; Zhao, X.Y. Biocrusts Alter the Pore Structure and Water Infiltration in the Top Layer of Rammed Soils at Weiyuan Section of the Great Wall in China. Coatings 2025, 15, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagna, V.; Bagarello, V.; Di Prima, S.; Guaitoli, F.; Iovino, M.; Keesstra, S.; Cerdà, A. Using Beerkan experiments to estimate hydraulic conductivity of a crusted loamy soil in a Mediterranean vineyard. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 2019, 67, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedunkova, O.; Kuznietsov, P.; Mandryk, O. Study of the dominant modes of formation and variability of potentially toxic element concentrations and their impact on environmental quality. Chemosphere 2025, 388, 144688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.J.; Fei, L.J.; Liu, L.H.; Chen, N.S.; Hao, K.; Li, Z.J. Soil Water Movement Characteristics in Muddy and Fertilizer Water Solution Infiltration Under Film Hole Irrigation Affected by Multiple Factors. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2021, 35, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Fei, L.J.; Li, Y.B. Infiltration characteristics of film hole irrigation under the influence of multiple factors. Irrig. Drain. 2020, 69, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Depth (cm) | Particle Size Distribution % | Physical Clay Content d0.01/% | Soil Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay (d < 0.002 mm) | Silt (0.002 mm < d < 0.02 mm) | Sandy(d > 0.02 mm) | |||

| 0~30 | 7.26 | 30.59 | 62.15 | 24.60 | Sandy Loam |

| Soil Density (g/cm3) | Initial Moisture Content (%) | Saturation Moisture Content (%) | Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity (cm/min) | Initial Ammonium Nitrogen Content (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.35 | 2.65 | 41.23 | 0.03514 | 19.35 |

| Treatment | Muddy Water Sediment Concentration/% | Physical Clay Content/% | Applied Nitrogen Concentration/mg/L | Pressure Head/cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 1 (3) | 1 (9.35) | 1 (900) | 1 (1) |

| T2 | 1 (3) | 2 (29.63) | 2 (600) | 2 (3) |

| T3 | 1 (3) | 3 (40.42) | 3 (300) | 3 (5) |

| T4 | 2 (6) | 1 (9.35) | 2 (600) | 3 (5) |

| T5 | 2 (6) | 2 (29.63) | 3 (300) | 1 (1) |

| T6 | 2 (6) | 3 (40.42) | 1 (900) | 2 (3) |

| T7 | 3 (9) | 1 (9.35) | 3 (300) | 2 (3) |

| T8 | 3 (9) | 2 (29.63) | 1 (900) | 3 (5) |

| T9 | 3 (9) | 3 (40.42) | 2 (600) | 1 (1) |

| T10 (verification experiment) | 4 | 20.25 | 450 | 4 |

| Parameter | 60 min | 300 min | 600 min | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | d0.01 | N | H | ρ | d0.01 | N | H | ρ | d0.01 | N | H | |

| k1 | 10.63 | 10.36 | 8.53 | 7.72 | 36.71 | 37.31 | 29.44 | 27.29 | 70.60 | 70.99 | 56.53 | 53.83 |

| k2 | 7.87 | 7.96 | 8.17 | 8.59 | 27.40 | 26.20 | 28.67 | 28.84 | 52.97 | 50.67 | 56.11 | 55.06 |

| k3 | 6.37 | 6.56 | 8.17 | 8.56 | 21.83 | 22.44 | 27.83 | 29.82 | 42.44 | 44.36 | 53.38 | 57.13 |

| Range | 4.26 | 3.80 | 0.36 | 0.88 | 14.88 | 14.87 | 1.61 | 2.54 | 28.16 | 26.63 | 3.15 | 3.30 |

| Degree of primary and secondary | ρ > d0.01 > H > N | ρ > d0.01 > H > N | ρ > d0.01 > H > N | |||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t value | 3.29 (p < 0.05) | 22.79 (p < 0.05) | 20.87 (p < 0.05) | 2.22 (p < 0.05) | 7.81 (p < 0.05) | 99.14 (p < 0.05) |

| Parameter | Initial Infiltration Rate i0 | Stable Infiltration Rate if | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | d0.01 | N | H | ρ | d0.01 | N | H | |

| k1 | 1.6967 | 1.6167 | 1.2800 | 1.1833 | 0.1121 | 0.1121 | 0.0907 | 0.0871 |

| k2 | 1.1300 | 1.1500 | 1.2733 | 1.2467 | 0.0846 | 0.0803 | 0.0893 | 0.0867 |

| k3 | 0.8600 | 0.9200 | 1.1333 | 1.2567 | 0.0677 | 0.0718 | 0.0844 | 0.0905 |

| Range | 0.8367 | 0.6967 | 0.1467 | 0.0733 | 0.0444 | 0.0403 | 0.0063 | 0.0038 |

| Degree of primary and secondary | ρ > d0.01 > N > H | ρ > d0.01 > N > H | ||||||

| Experimental Treatments | Experimental Factors | Δθ | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | d0.01 | N | H | |||

| T1 | 3 | 9.35 | 300 | 2 | 0.1240 | 0.9933 |

| T2 | 3 | 29.63 | 600 | 4 | 0.1776 | 0.9949 |

| T3 | 3 | 40.42 | 900 | 6 | 0.2011 | 0.9995 |

| T4 | 6 | 9.35 | 600 | 6 | 0.1698 | 0.9972 |

| T5 | 6 | 29.63 | 900 | 2 | 0.2102 | 0.9896 |

| T6 | 6 | 40.42 | 300 | 4 | 0.2557 | 0.9945 |

| T7 | 9 | 9.35 | 900 | 4 | 0.2224 | 0.9990 |

| T8 | 9 | 29.63 | 300 | 6 | 0.2973 | 0.9979 |

| T9 | 9 | 40.42 | 600 | 2 | 0.3090 | 0.9735 |

| k1 | 0.1676 | 0.1721 | 0.2112 | 0.2144 | ||

| k2 | 0.2119 | 0.2285 | 0.2188 | 0.2186 | ||

| k3 | 0.2764 | 0.2553 | 0.2258 | 0.2229 | ||

| Range | 0.1088 | 0.0832 | 0.0146 | 0.0085 | ||

| Degree of primary and secondary | ρ > d0.01 > N > H | |||||

| Experimental Treatments | Measured Value | Calculation Value | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| T10 | 0.2025 | 0.2204 | 8.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jie, F.; Peng, Y. Coupled Water–Nitrogen Transport and Multivariate Prediction Models for Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12765. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312765

Jie F, Peng Y. Coupled Water–Nitrogen Transport and Multivariate Prediction Models for Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12765. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312765

Chicago/Turabian StyleJie, Feilong, and Youliang Peng. 2025. "Coupled Water–Nitrogen Transport and Multivariate Prediction Models for Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12765. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312765

APA StyleJie, F., & Peng, Y. (2025). Coupled Water–Nitrogen Transport and Multivariate Prediction Models for Muddy Water Film Hole Irrigation. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12765. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312765