Experimental Study of Micro/Macro Damage and Failure Mechanism of Granite Subjected to Different Impact Velocities and Numbers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Description of Rock Specimens

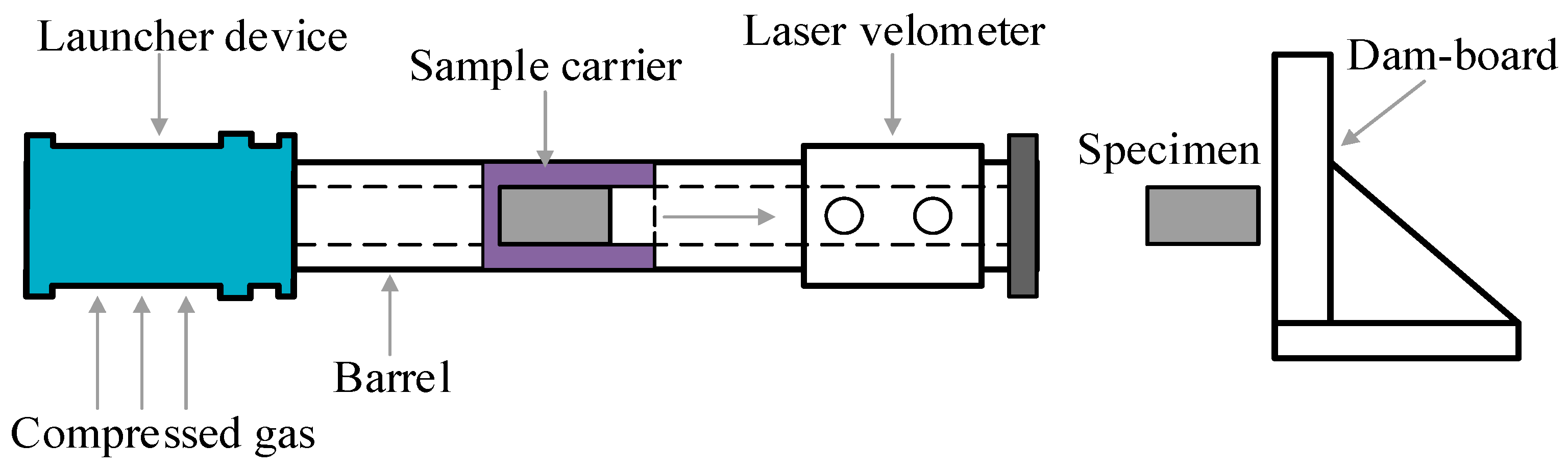

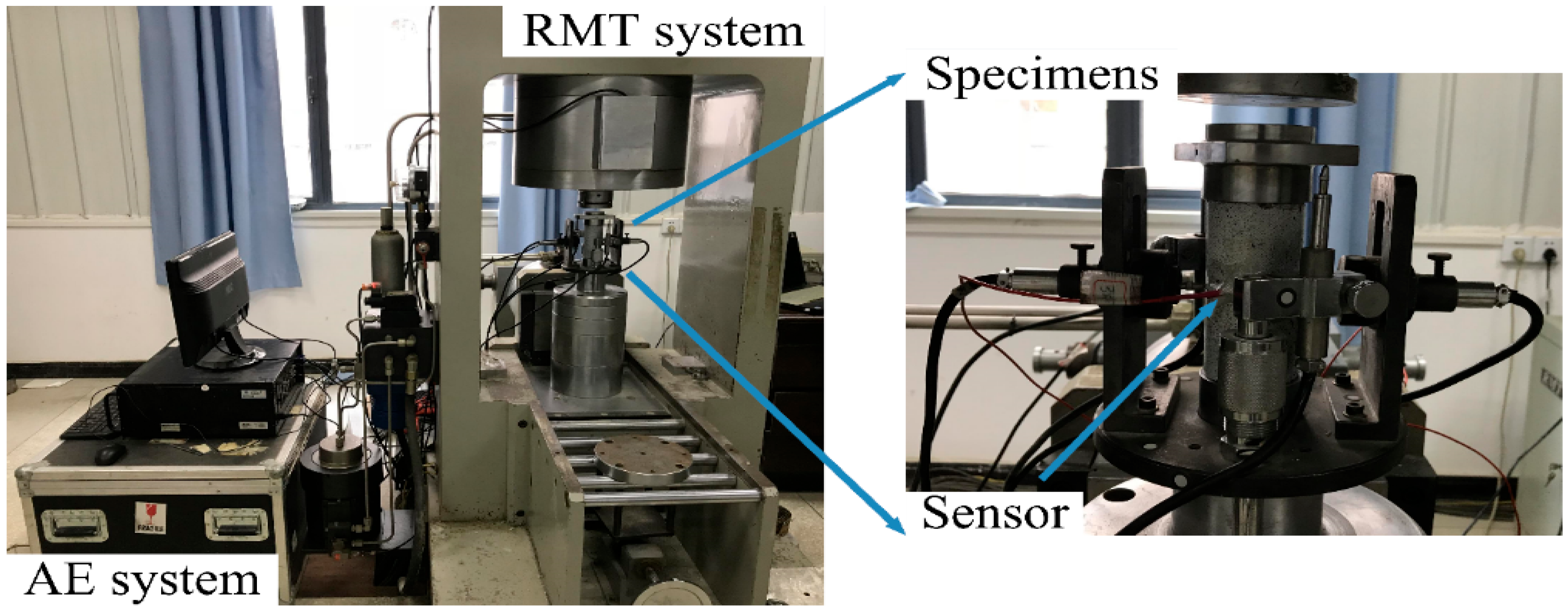

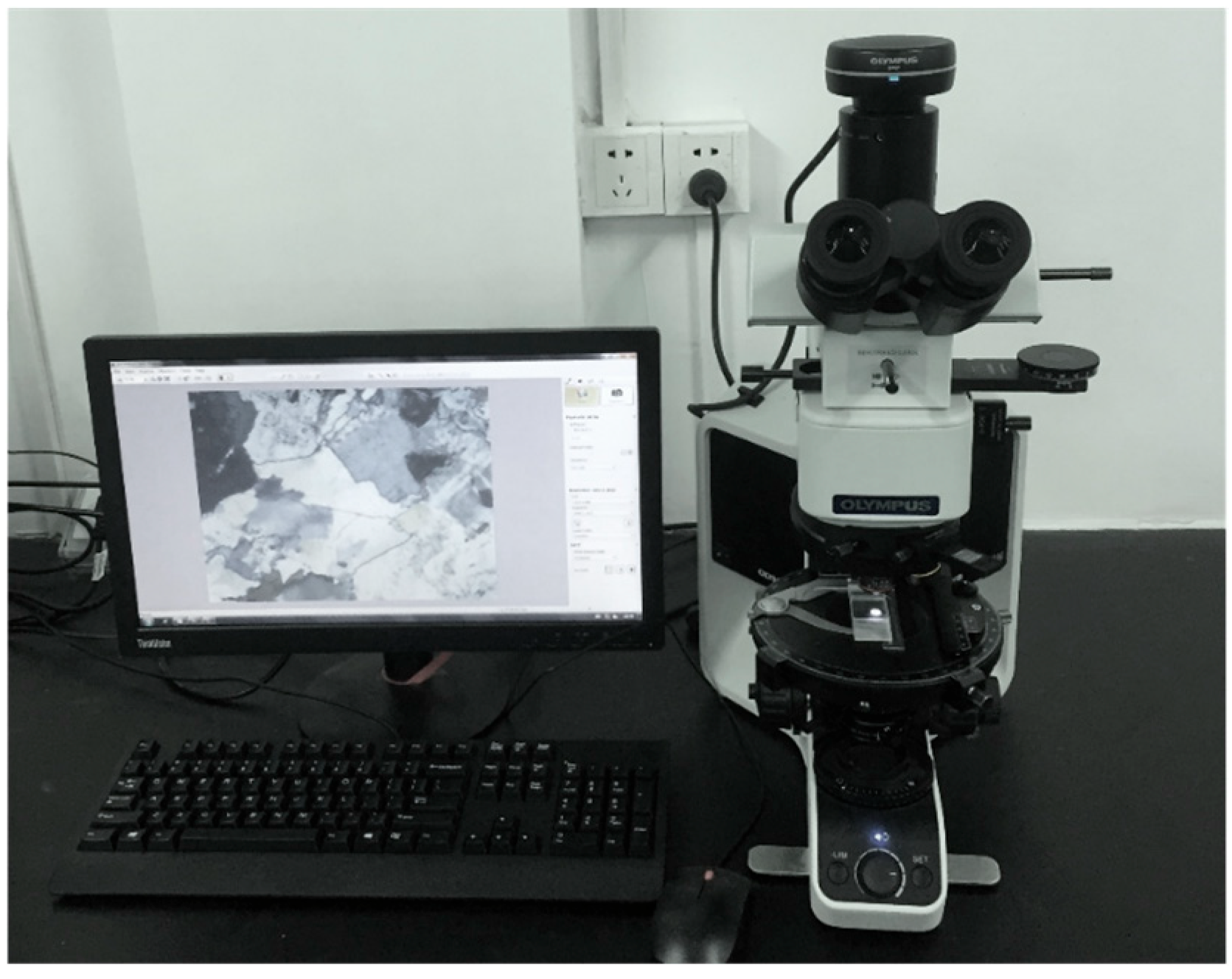

2.2. Test Equipment

2.3. Test Procedure

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Internal Damage Level

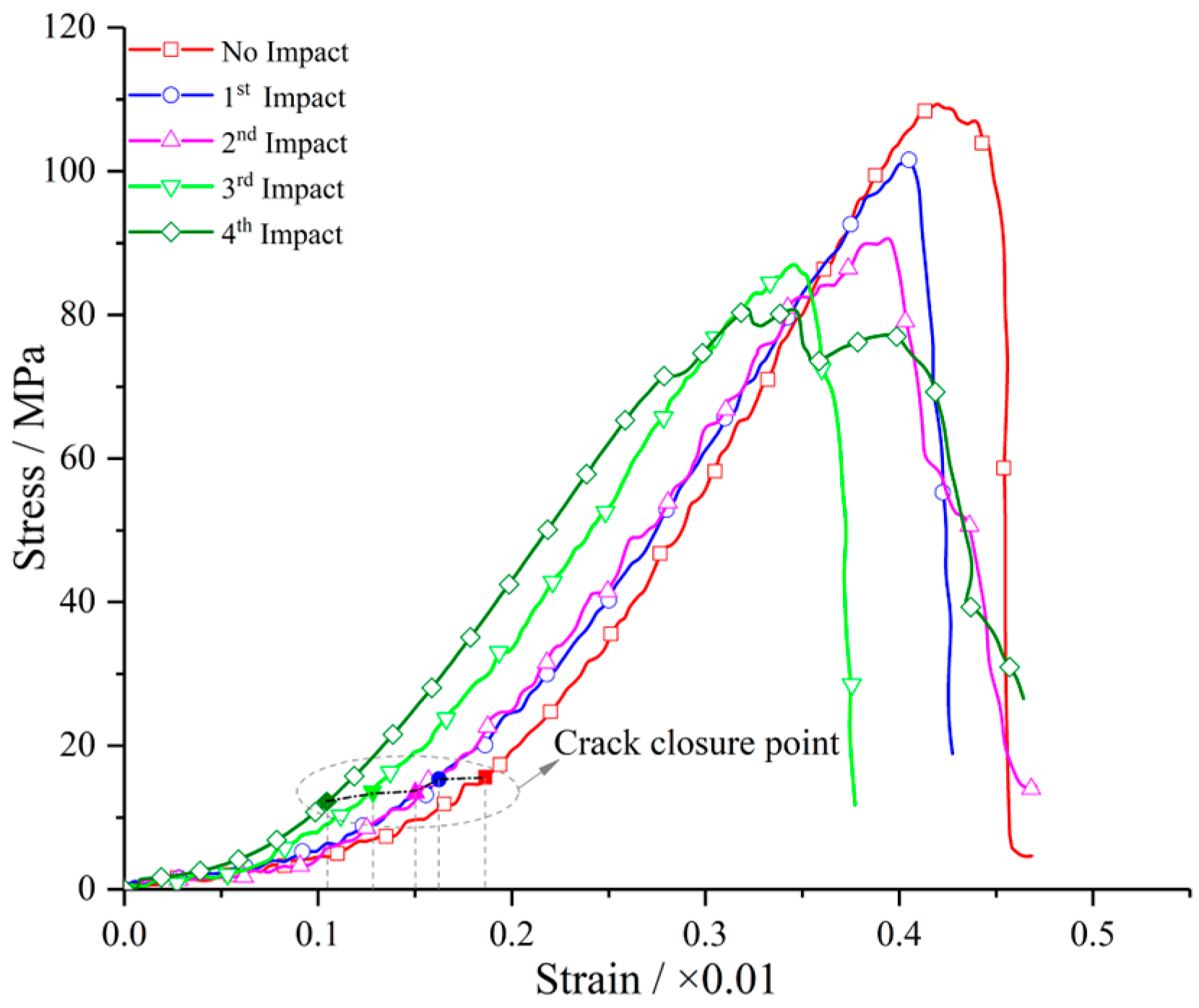

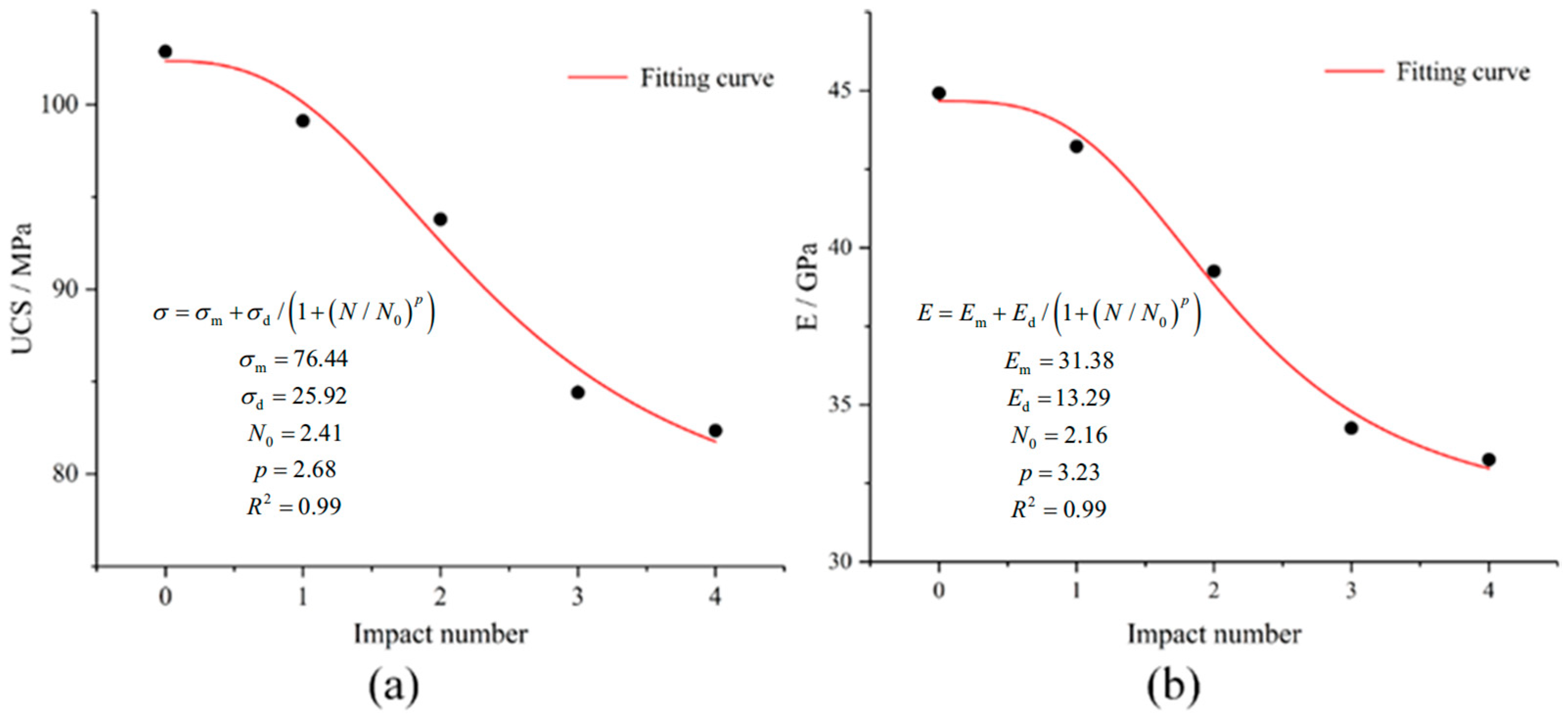

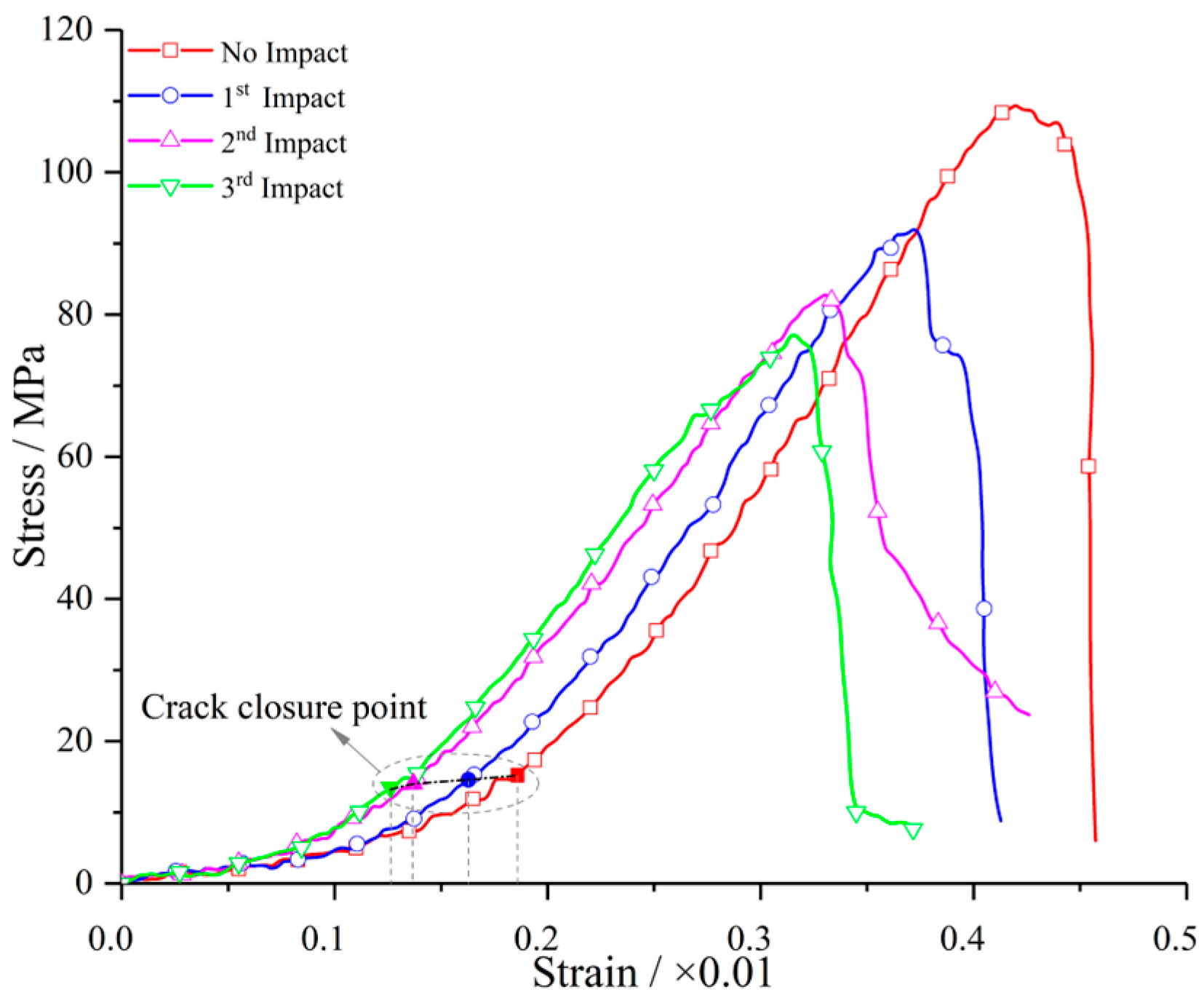

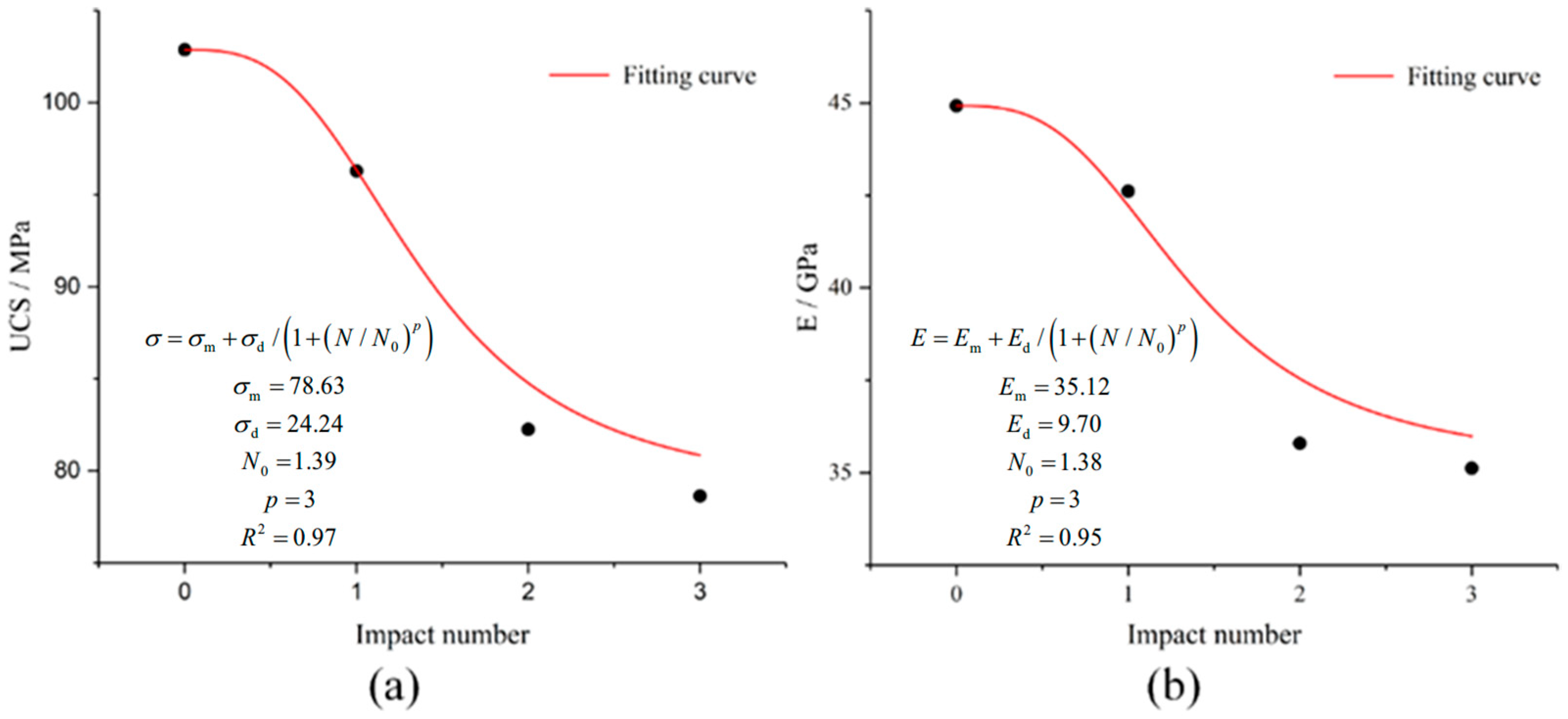

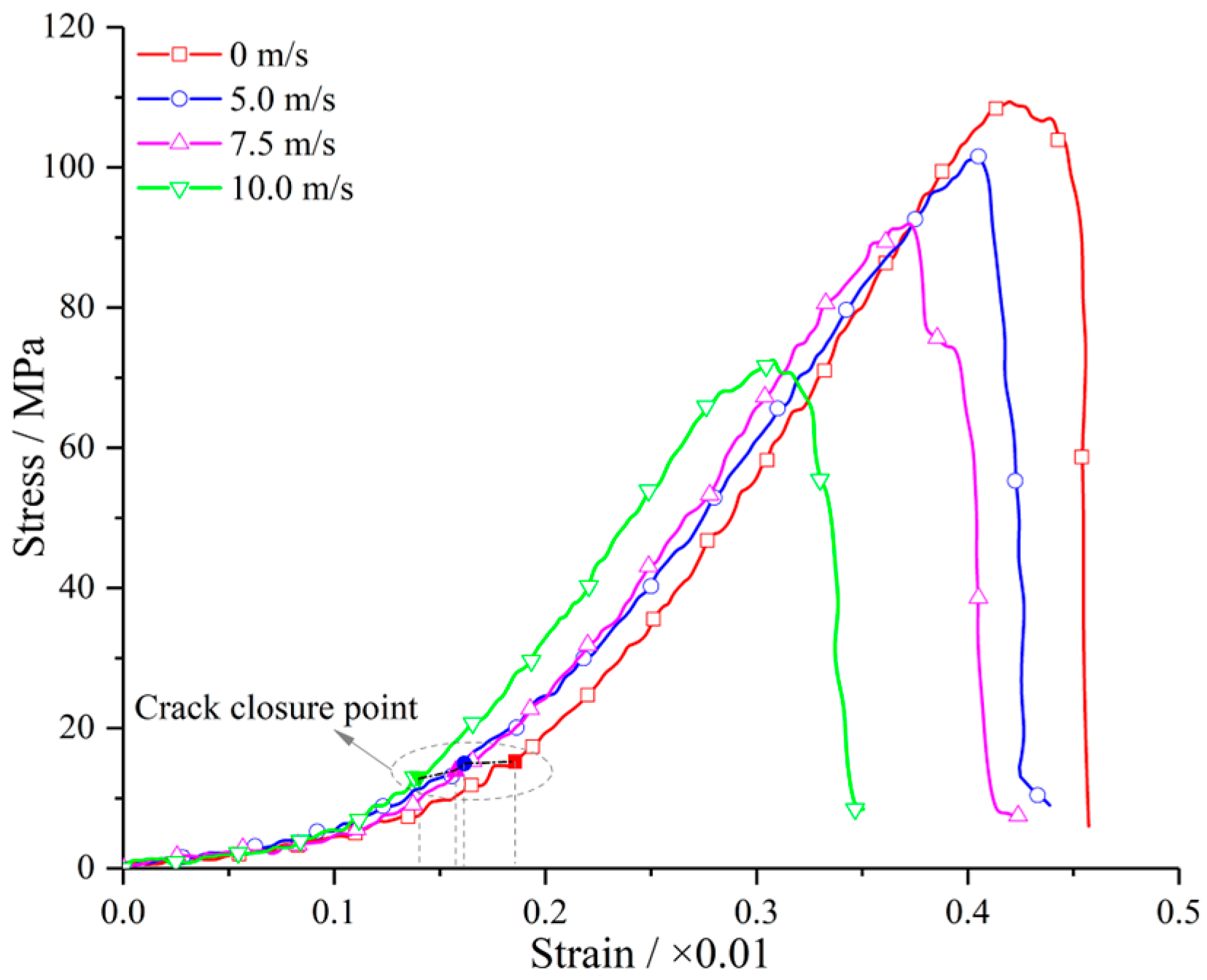

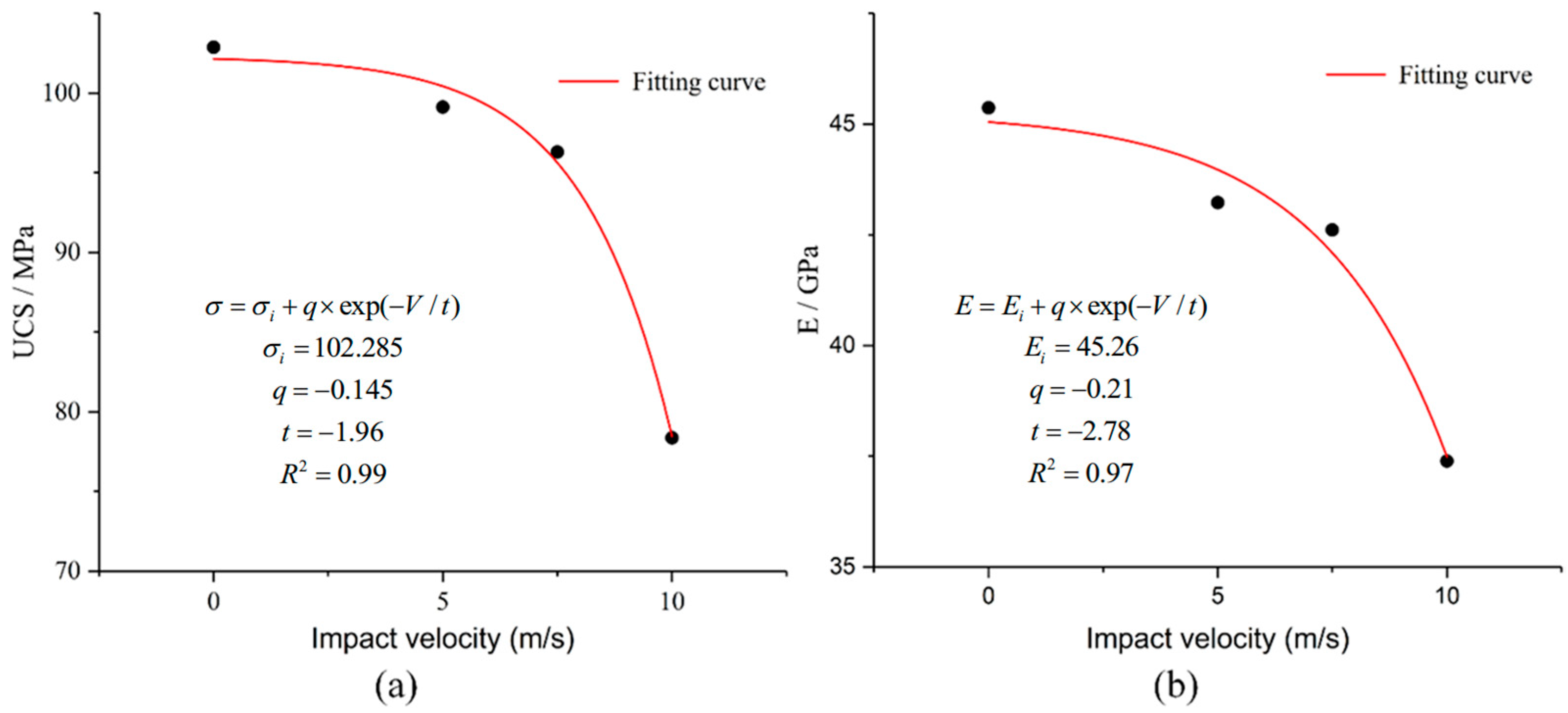

3.1.1. Mechanical Properties Under Different Impact Velocities and Repeated Impact Numbers

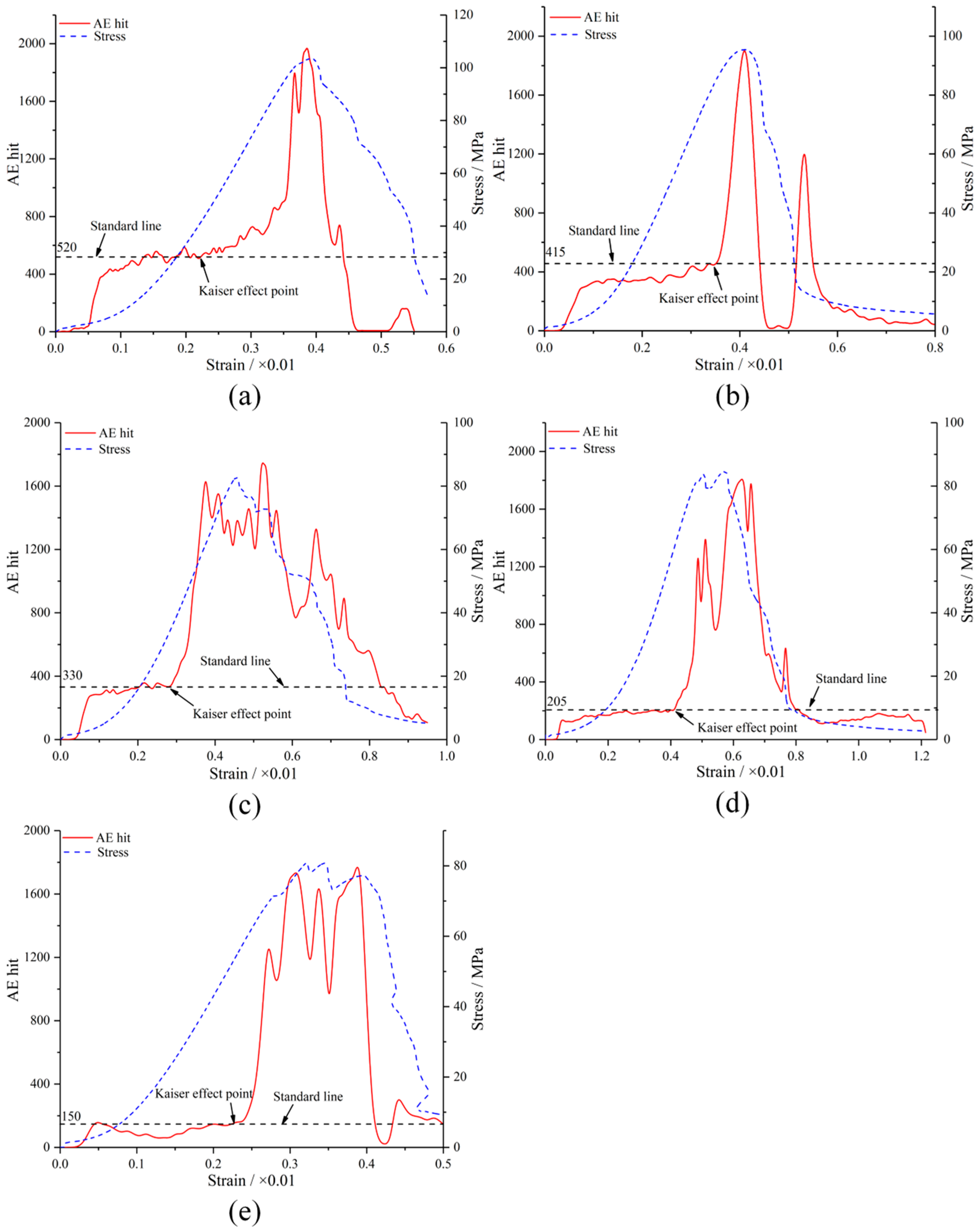

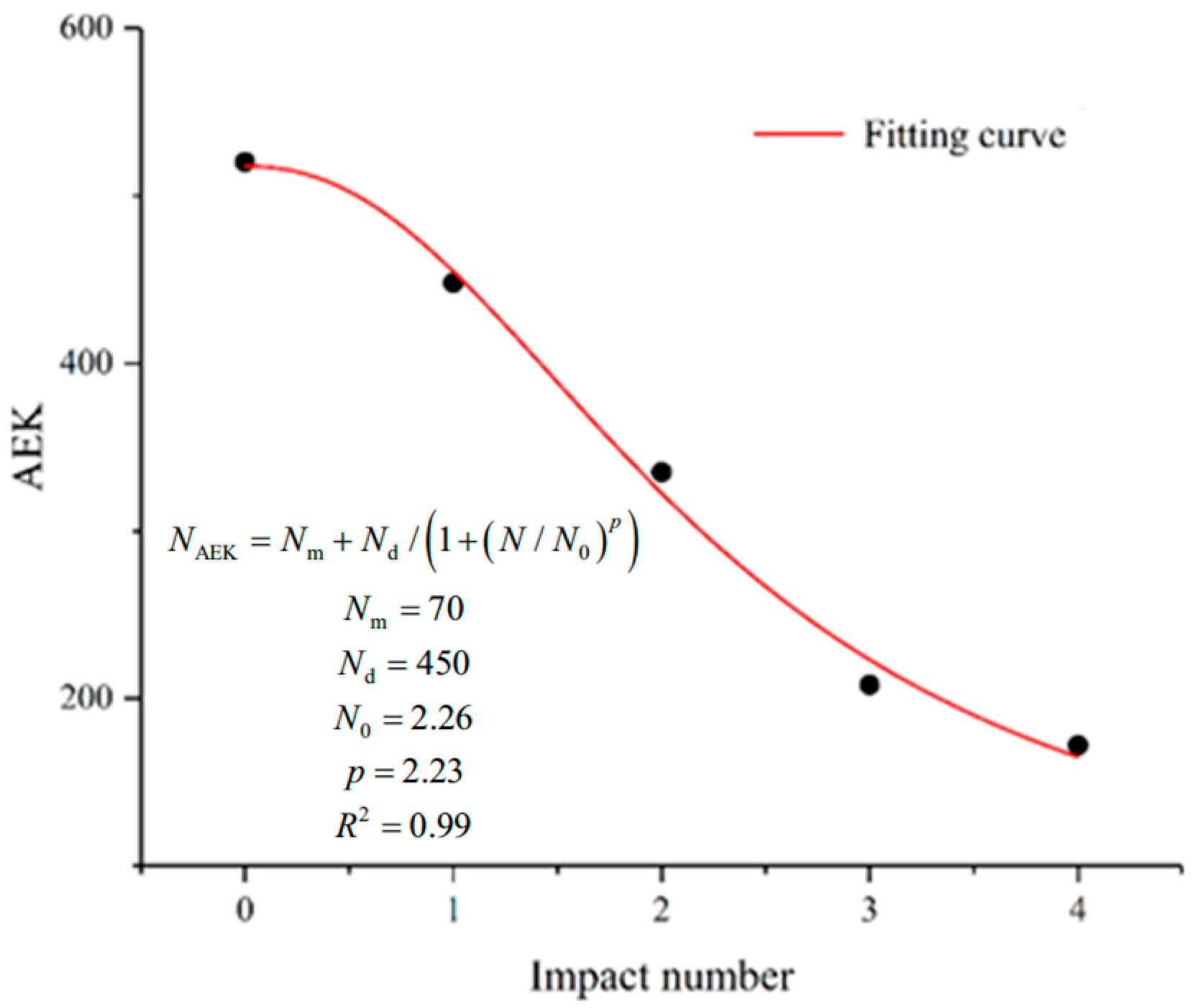

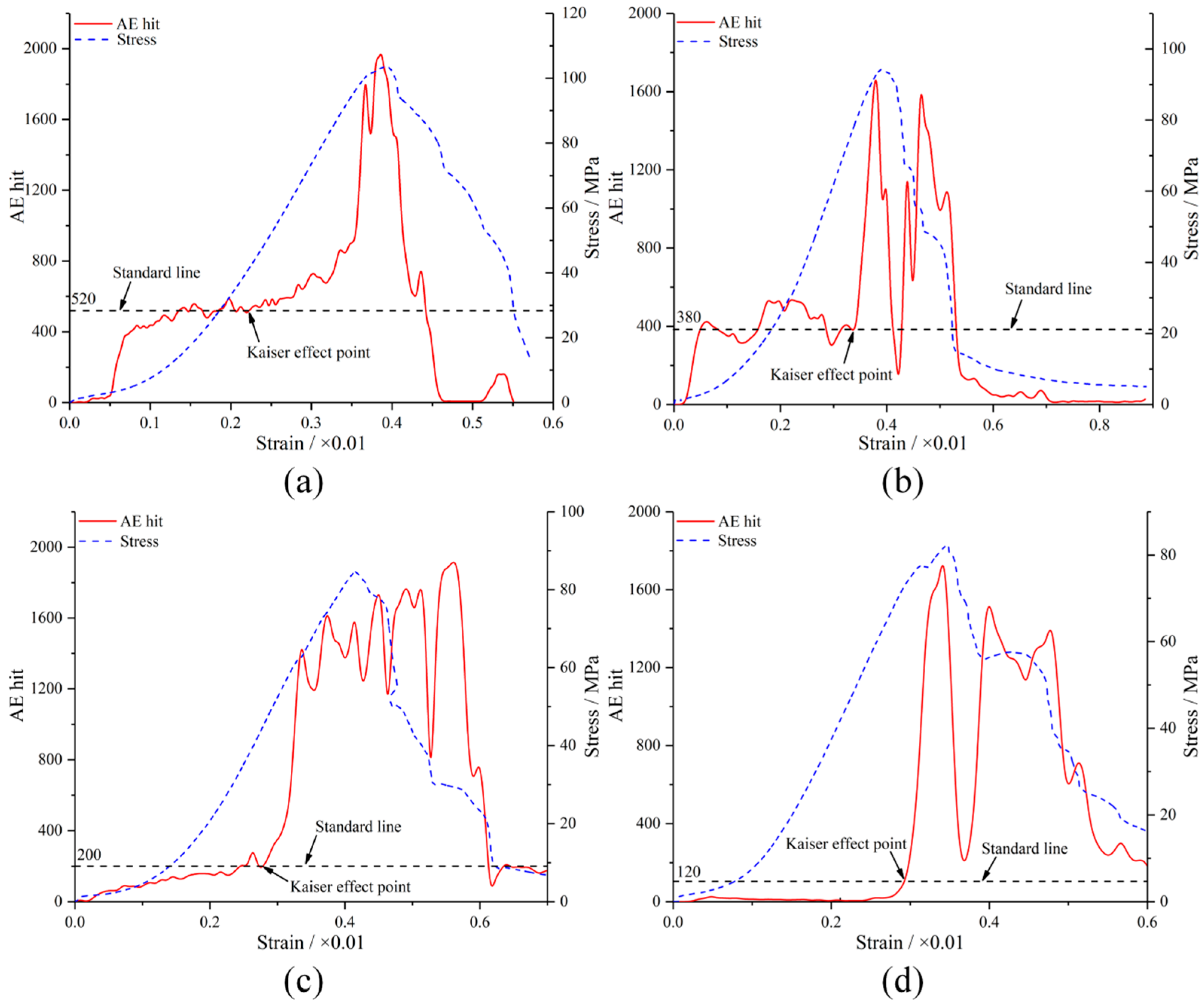

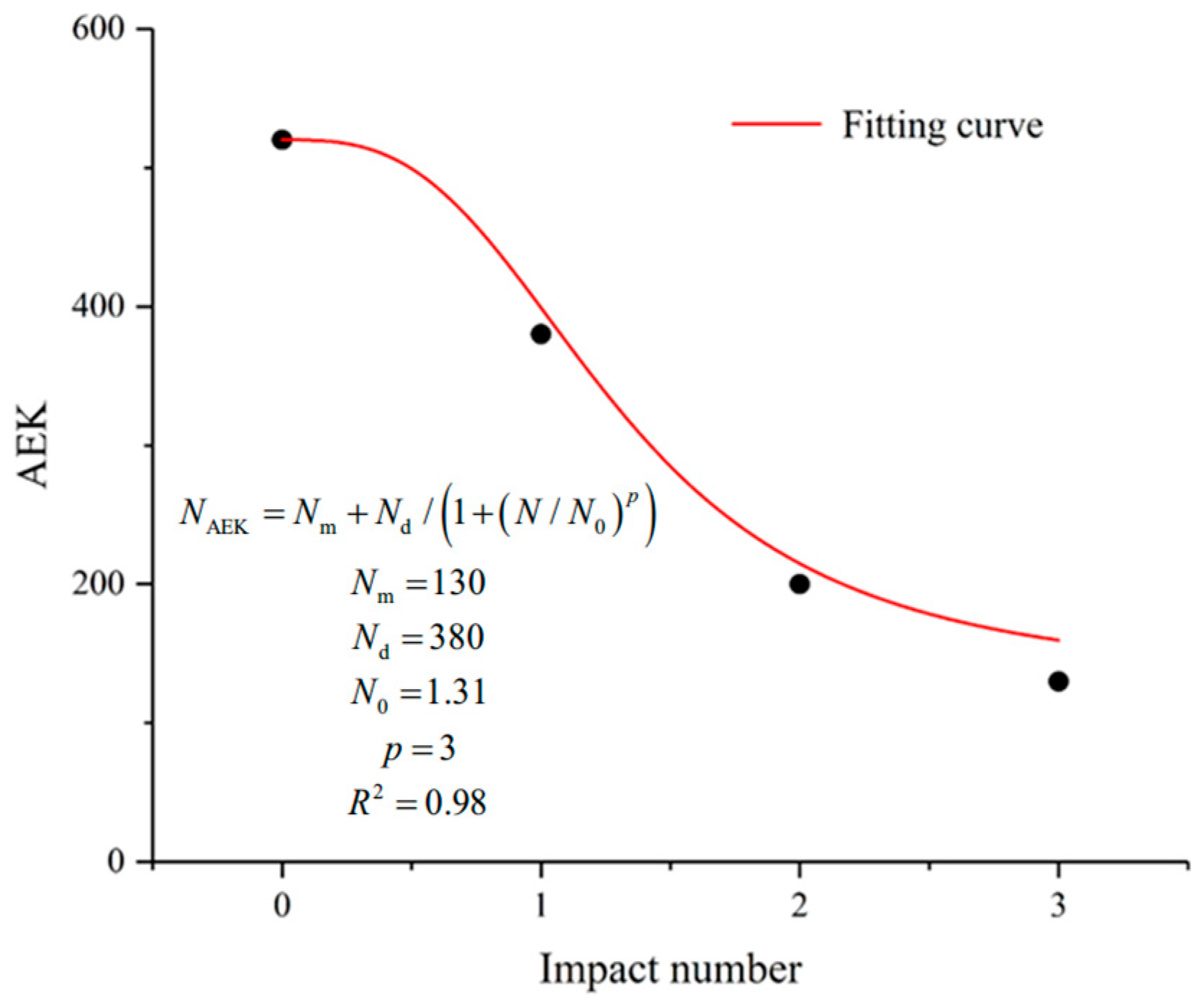

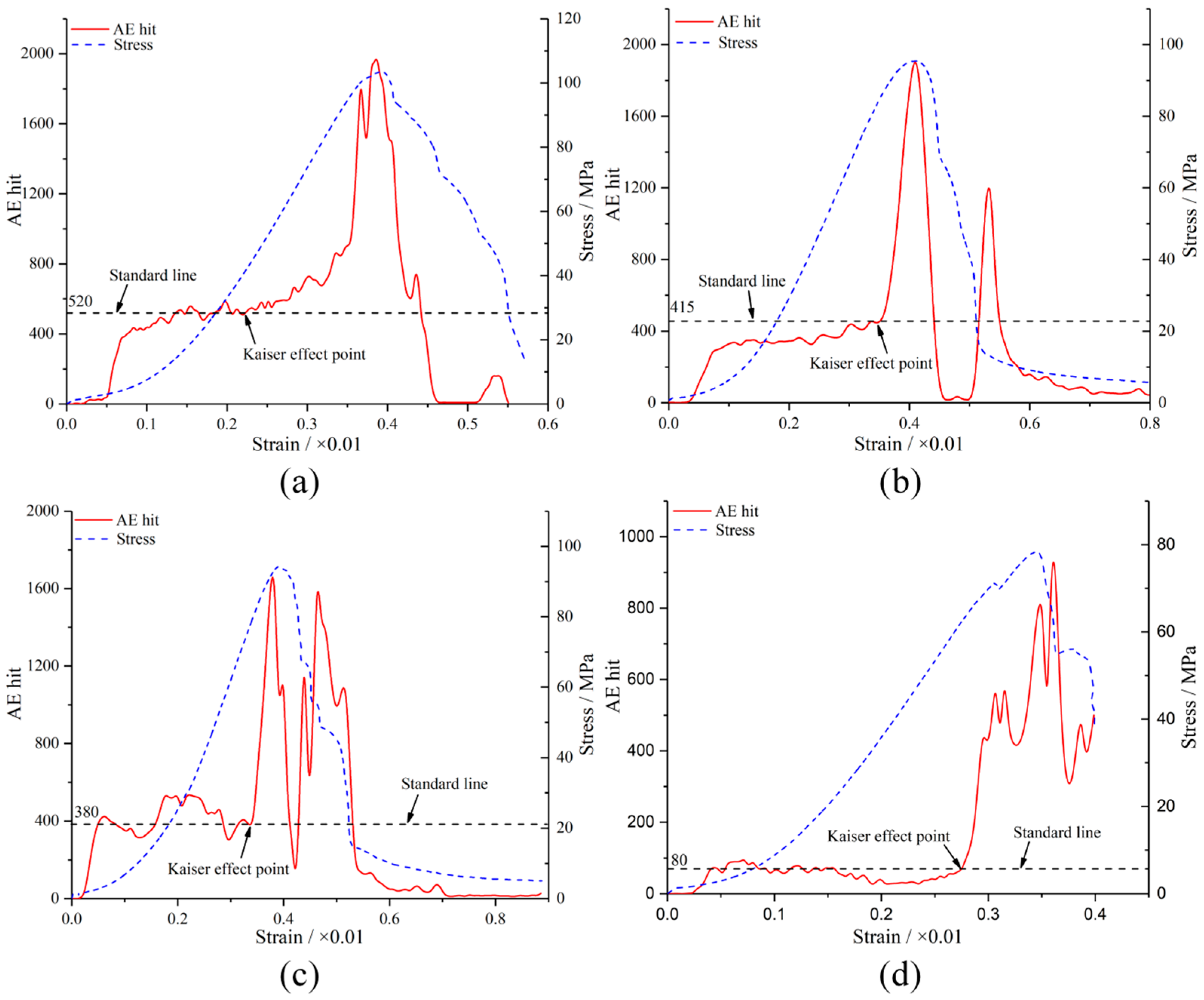

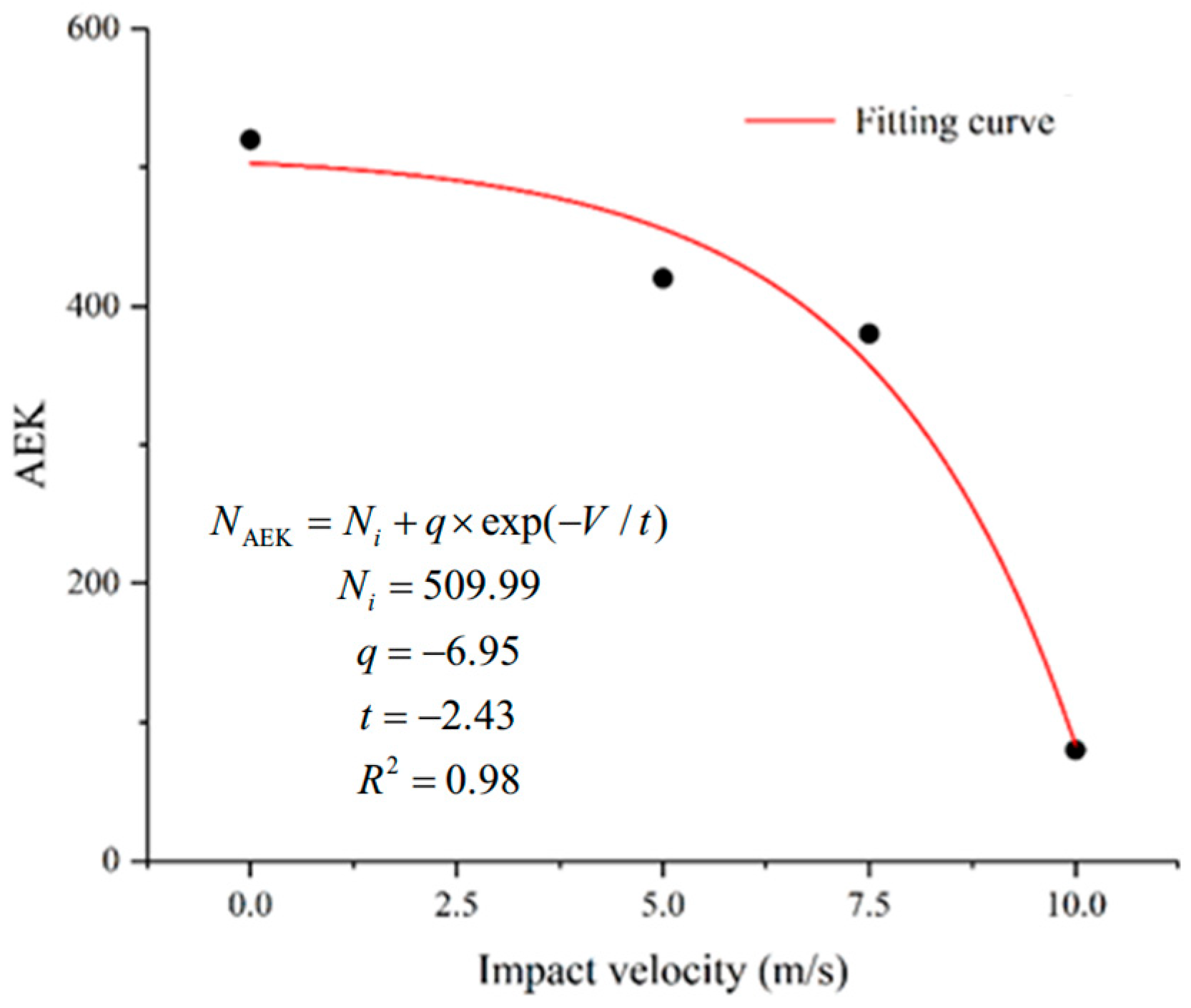

3.1.2. Micro-Failure Process Under Different Impact Velocities and Repeated Impact Numbers

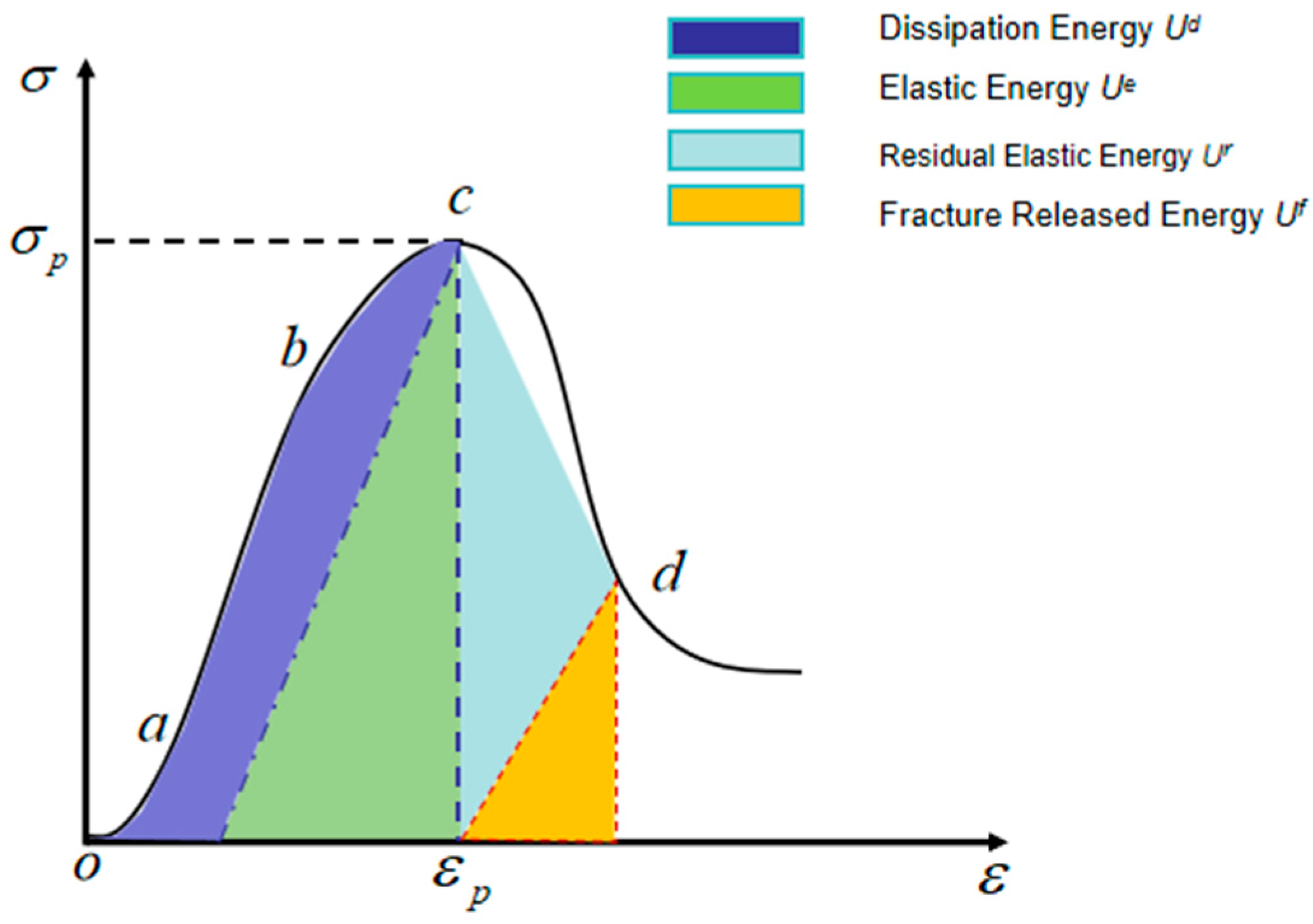

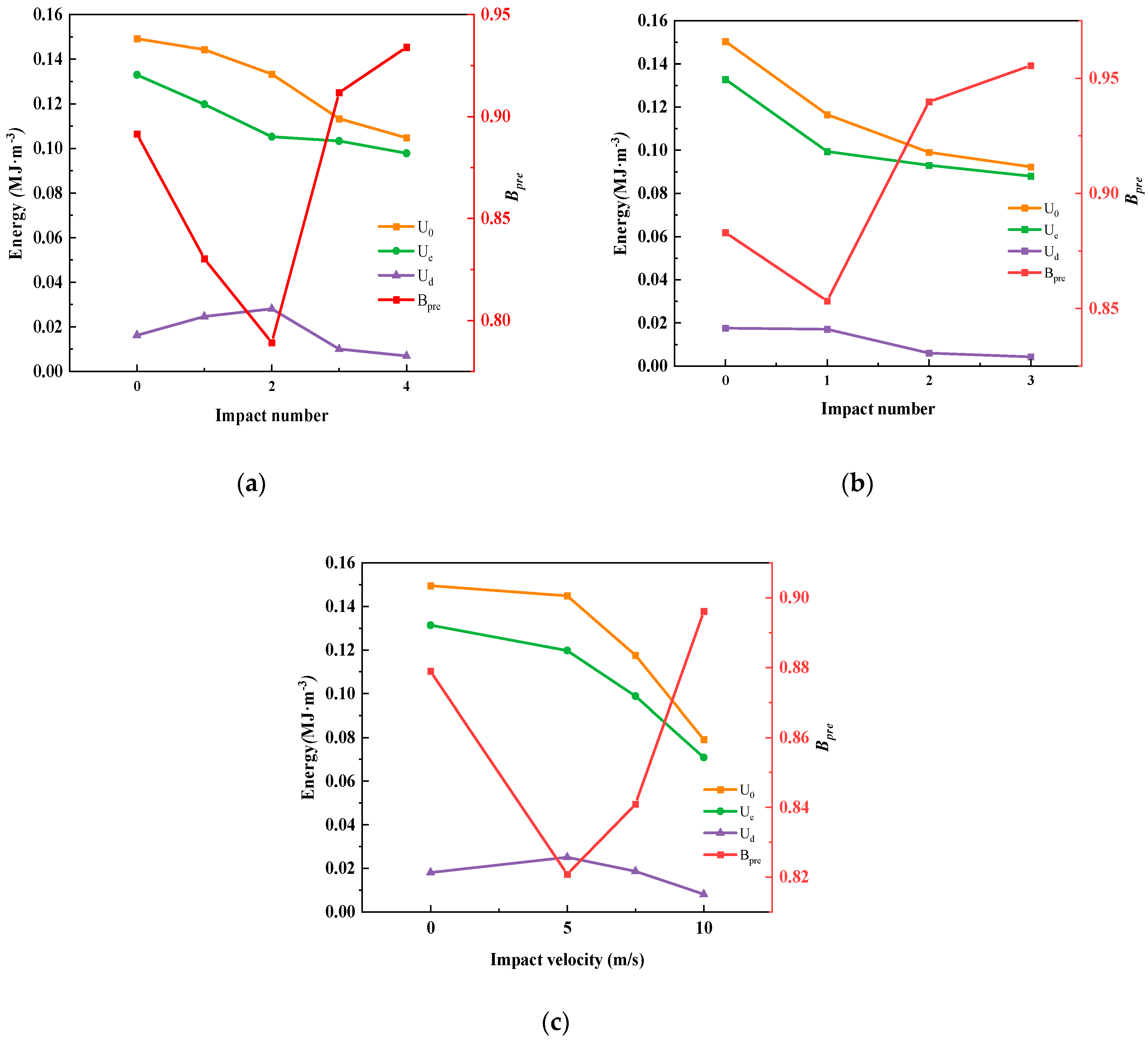

3.1.3. Energy Evolution

3.2. Local Failure Level

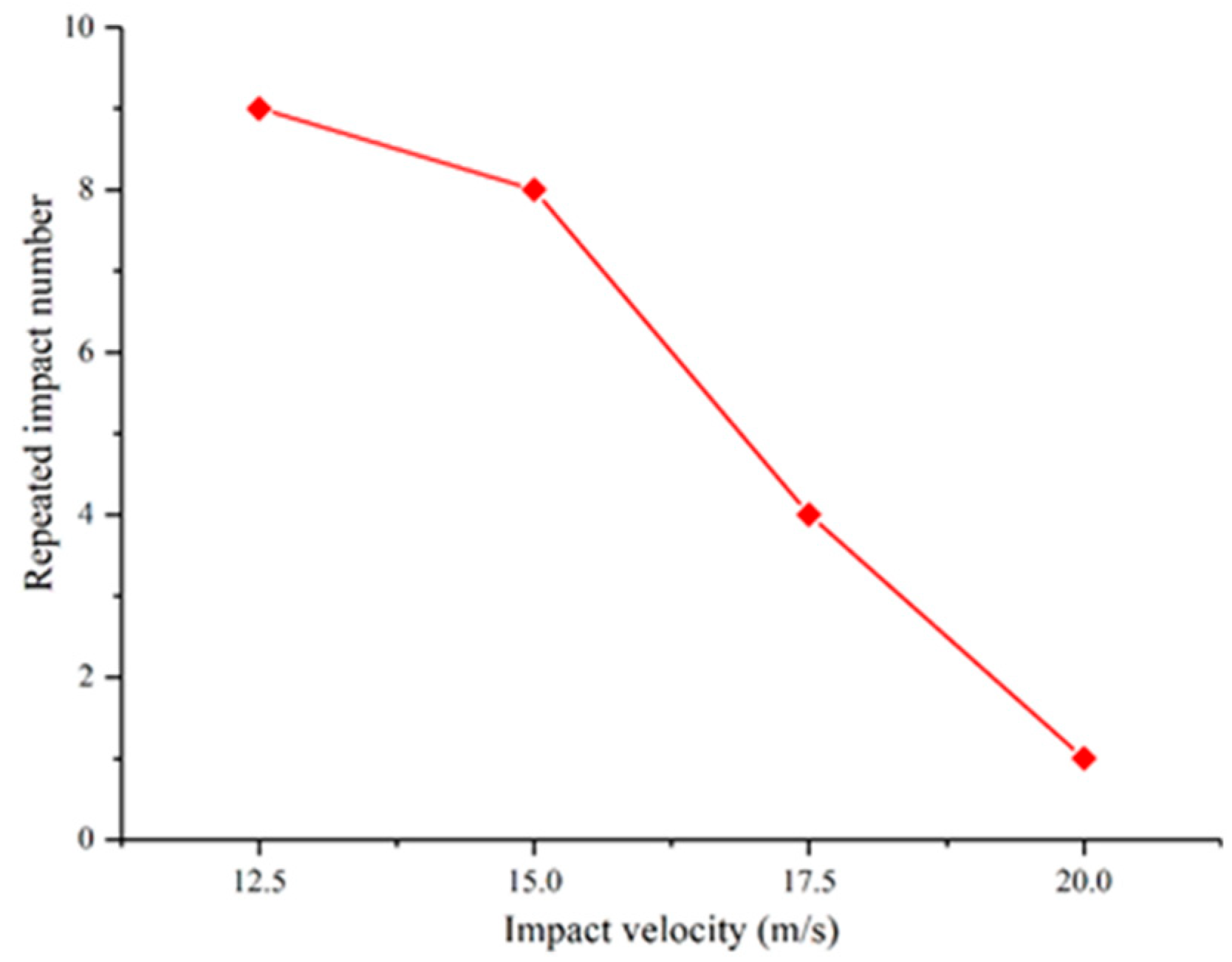

3.2.1. Repeated Impact Number That Causes the Specimen to Break Completely

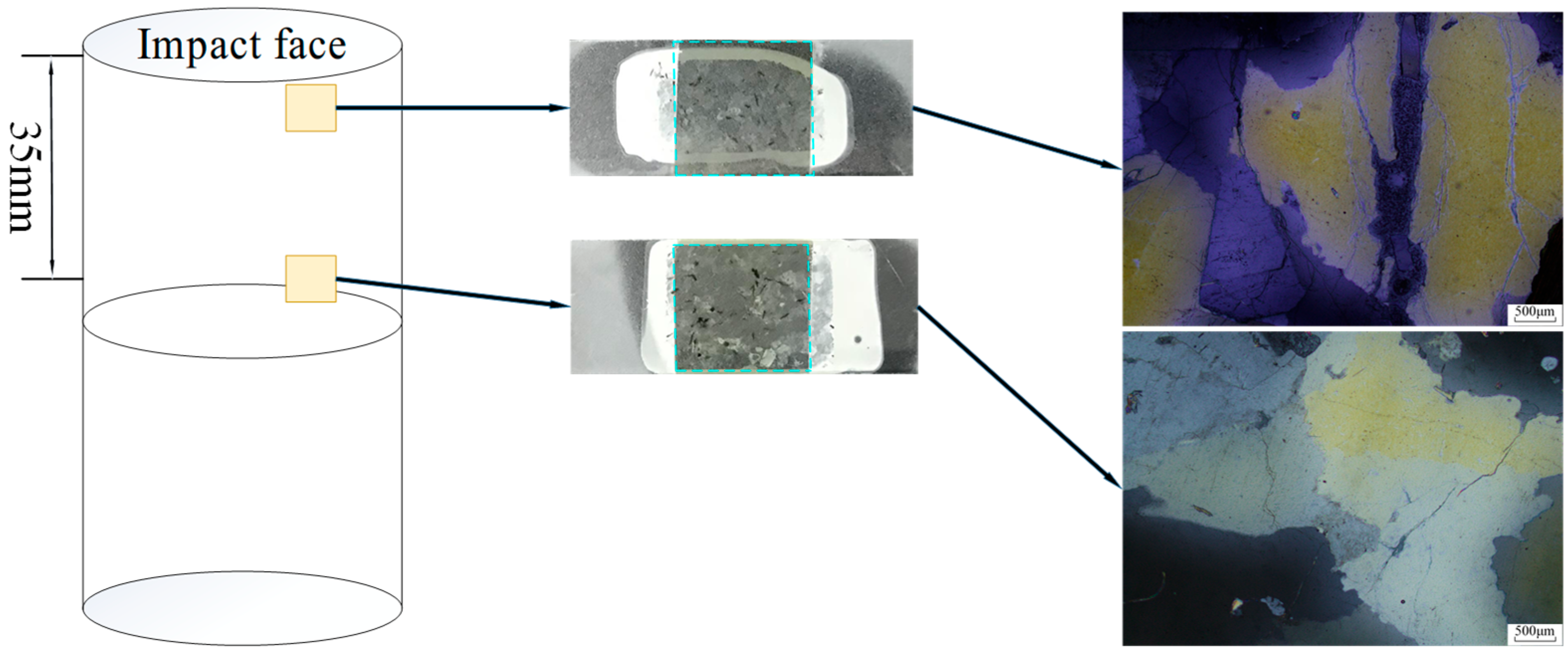

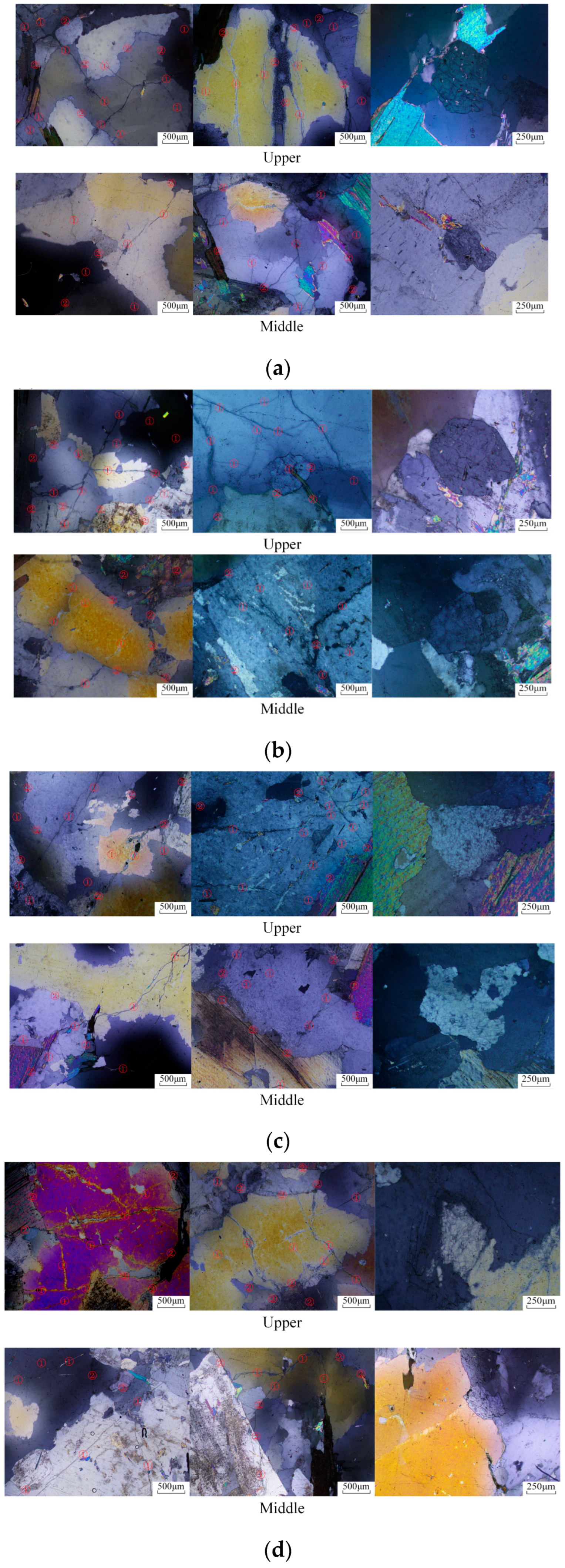

3.2.2. Microscopic Observations

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- At the internal damage level, when the impact velocity increases from 5.0 to 10.0 m/s, the repeated impact number that changes a granite specimen from internal damage to local failure decreases from 4 to 1. The UCS and Young’s modulus monotonously decrease with an increasing number of repeated impacts, and the decrease is significantly weakened for the last impact (impact only induces internal damage).

- (2)

- At the internal damage level, regarding the behavior of a granite specimen after a single impact, the proposed negative exponential models can well capture the variation in UCS and Young’s modulus with the impact velocity. When the impact velocity increases from 5.0 to 10.0 m/s, both the UCS and Young’s modulus of the granite specimen gradually decrease, experiencing a more obvious reduction when the impact velocity exceeds 7.5 m/s.

- (3)

- At the local failure level, when the impact velocity increases from 12.5 to 20.0 m/s, the repeated impact number that changes a granite specimen from local failure to a completely broken state decreases from 9 to 1. As the impact velocity increases from 12.5 to 15.0 m/s, the micro-crack density of the broken granite specimen increases slightly, while the complete breakage of small grains increases significantly. When the impact velocity further increases to 17.5 m/s, the micro-crack density of the broken granite specimen decreases as the complete breakage of small grains obviously increases. When the impact velocity continues to increase to 20.0 m/s, the granite specimen is completely broken under a single impact.

- (4)

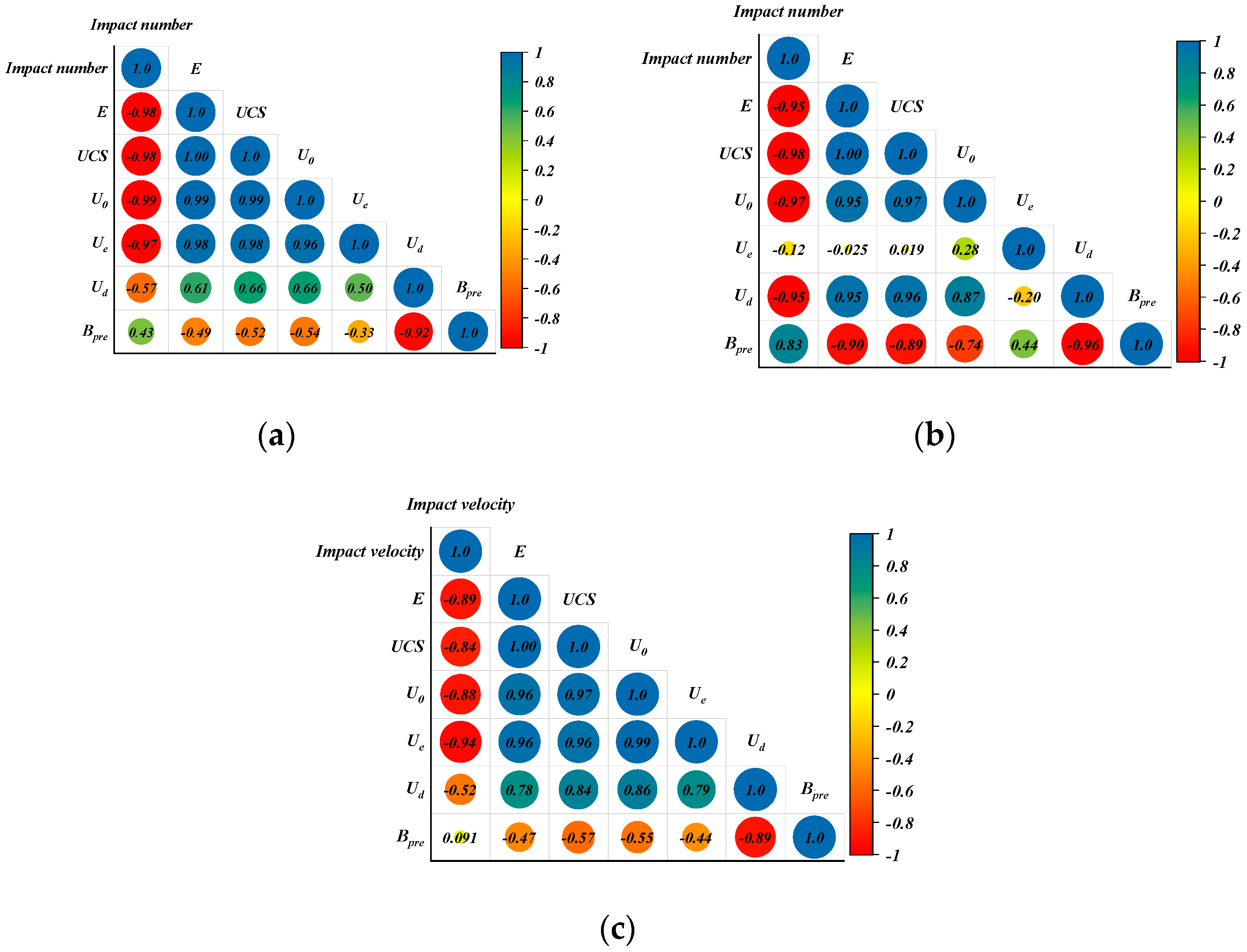

- Different repeated impact numbers and velocities have significant effects on the brittle failure of granite, and there is an obvious negative correlation with granite’s mechanical property parameters (E and UCS) and the total energy absorbed before the peak (U0). This indicates that the more often and the faster the granite is impacted, the more likely it is to fail in a brittle manner. Additionally, the higher the impact velocity and frequency, the greater the negative impact on the mechanical properties and the total energy it can absorb before peak stress is reached.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bunce, C.M.; Cruden, D.M.; Morgenstern, N.R. Assessment of the hazard from rock fall on a highway. Can. Geotech. J. 1997, 34, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.T.; Wong, R.H.C.; Liu, J.; Lee, C.F. Rockfall Hazard Analysis for Hong Kong Based on Rockfall Inventory. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2003, 36, 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoopes, G.R.; Sheridan, M.F. Giant debris avalanches from the Colima Volcanic Complex, Mexico: Implications for long-runout landslides (>100 km) and hazard assessment. Geology 1992, 20, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.; Giacomini, A.; Thoeni, K. Qualitative Rockfall Hazard Assessment: A Comprehensive Review of Current Practices. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 2865–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Yu, Z.; Lv, Y.; Peng, J.; Song, S.; Yao, Z. Rockfall hazard assessment in the Taihang grand canyon scenic area integrating regional-scale identification of potential rockfall sources. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labiouse, V.; Heidenreich, B. Half-scale experimental study of rockfall impacts on sandy slopes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009, 9, 1981–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, N.; Pandit, K.; Sarkar, S.; Pain, A. Various aspects of rockfall hazards along the mountain roads in India: A systematic review. Indian Geotech. J. 2025, 55, 2007–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Xiao, A.Y. Non-Circular Rock-Fall Motion Behavior Modeling by the Eccentric Circle Model. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2010, 44, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Dai, F.; Liu, Y.; Xu, N.W.; Zhao, T. Effects of strain rate on the mechanical and fracturing behaviors of rock-like specimens containing two unparallel fissures under uniaxial compression. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 110, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, K.T.; Hogan, J.D.; Kimberley, J.; Stickle, A. A review of mechanisms and models for dynamic failure, strength, and fragmentation. Planet. Space Sci. 2015, 107, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.B.; Zhao, J. A Review of Dynamic Experimental Techniques and Mechanical Behaviour of Rock Materials. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2013, 47, 1411–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.X.; Yang, S.Q.; Gu, J.C.; Zhang, Q.B.; Lu, W.B.; Jing, H.W.; Wang, Z.L. JHR constitutive model for rock under dynamic loads. Comput. Geotech. 2019, 108, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.H.; Wang, H.; Qiu, X.; Wang, C.; Lin, H.; Qiao, Q. Damage characteristics and fracture behaviour of marble after cycle impact loading. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2023, 125, 103903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Liu, J.L.; Li, P.F. Dynamic behaviour and nonlinear ultrasonic characteristic of sandstone under intermittent cyclic impact loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 325, 111346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigopoulos, I.; Tsikouras, B.; Pomonis, P.; Hatzipanagiotou, K. Petrographic Investigation of Microcrack Initiation in Mafic Ophiolitic Rocks Under Uniaxial Compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2012, 46, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, T.; Li, D. Dynamic Strength and Fracturing Behavior of Single-Flawed Prismatic Marble Specimens Under Impact Loading with a Split-Hopkinson Pressure Bar. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 50, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shao, Z. Investigation of Macroscopic Brittle Creep Failure Caused by Microcrack Growth Under Step Loading and Unloading in Rocks. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2016, 49, 2581–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, Z.; Huang, K.; Li, Y.; Peng, H.; Liang, Q.; Ma, K. Study on the evolution law and quantitative characterization of micro-crack propagation in the compressive failure process of rocks. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 155, 107743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Nemat-Nasser, S. Dynamic damage evolution in brittle solids. Mech. Mater. 1992, 14, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.L.; Jiang, Y.H.; Zou, Y.; Wong, L. Degradation mechanism of rock under impact loadings by integrated investigation on crack and damage development. J. Cent. South Univ. 2014, 21, 4646–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yin, T.; Guo, W.; Men, J.; Ma, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, D. Dynamic response and constitutive model of damaged sandstone after triaxial impact. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 163, 108450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xue, Y.; Ren, X.; Kong, F.; Liao, X. Dynamic response characteristics and damage calculation method of fractured rock mass under blasting disturbance. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2024, 192, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, L.; Fu, S.; Liu, B.; Li, X. Rate-dependent strength and crack damage thresholds of rocks at intermediate strain rate. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2023, 171, 105590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sheng, Q.; Li, N.; Fu, X. The influence of strain rate on the energy characteristics and damage evolution of rock materials under dynamic uniaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 3823–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dai, F. Dynamic Response and Failure Mechanism of Brittle Rocks Under Combined Compression-Shear Loading Experiments. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 747–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Cheng, S.; Sun, H.; Chen, X. Numerical investigation of rock sphere breakage upon oblique impact: Effect of the contact friction coefficient and impact angle. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 136, 104207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Cheng, S.; Song, P.; Mao, C. Effects of the impact angle on the coefficient of restitution in rockfall analysis based on a medium-scale laboratory test. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 3045–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Ma, H.; Weng, L.; Liu, Y.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Jin, G.; Chang, W. Fragmentation analyses of rocks under high-velocity impacts using the combined finite-discrete element simulation. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 998521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Weng, L.; Chu, Z.F. Numerical investigation of rock dynamic fragmentation during rockslides using a coupled 3D FEM-DEM method. J. Mt. Sci. 2022, 19, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tonon, F. Discrete Element Modeling of Rock Fragmentation upon Impact in Rock Fall Analysis. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2010, 44, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tonon, F. Dynamic validation of a discrete element code in modeling rock fragmentation. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2011, 48, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, E.; Liu, Y.; Chen, D. The disaster mechanism of stress waves and the damage constitutive model of deep tight sandstone under shock and impact loads. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 046623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, Q.; Tao, Z.; Hu, T. Insights into natural tuff as a building material: Effects of natural joints on fracture fractal characteristics and energy evolution of rocks under impact load. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 163, 108584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Gao, X.; Li, P.; Dong, B. Dynamic characteristics and fracture process of marble under repeated impact loading. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 276, 108926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.G.; Zhao, T.; Crosta, G.B.; Dai, F. Analysis of impact-induced rock fragmentation using a discrete element approach. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2017, 98, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Su, L.; Wang, B.; Miao, S.; Tian, H. Dynamic fragmentation of intact rock blocks and its influence on mobility: Insights from discrete element analysis. Landslides 2024, 21, 3103–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Du, X.; Huang, H. Progressive fragmentation of granular assemblies within rockslides: Insights from discrete-continuous numerical modeling. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 1174–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Dai, F.; Li, A.; Jiang, R. Dynamic Responses and Failure Behaviors of Saturated Rocks Subjected to Repetitive Compression–Shear Impacting. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 4697–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.F.; Li, H.; Xi, Y.; Wang, M. Effect of Cyclic Impact on the Dynamic Behavior of Thermally Shocked Granite. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 4473–4491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.H.; Zhu, W.C.; Niu, L.L.; Yu, M.; Chen, C.F. Dynamic Characteristics of Green Sandstone Subjected to Repetitive Impact Loading: Phenomena and Mechanisms. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2018, 51, 1921–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhu, J.; Qu, H.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, C. An experimental investigation on fatigue characteristics of granite under repeated dynamic tensions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2022, 158, 105185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Gao, X.; Li, P.; Dong, B. Dynamic characteristics and energy evolution of granite subjected to coupled static–cyclic impact loading. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2023, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bu, J.; Wang, T.; Song, H. Dynamic features and cracking process of limestone exposed to repetitive impact loading. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Huang, J.; Gong, H.; Wang, J. Progressive damage and fracture behavior of brittle rock under multi-axial prestress constraint and cyclic impact load coupling. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, E.; Liu, Y.; Yue, W.; Chen, D. Research on the Energy Dissipation Characteristics and Stress Wave Spectrum Analysis of Red Sandstone Subjected to Progressive Load Cyclic Impact. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 10849–10876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuschlé, T.; Haore, S.G.; Darot, M. The effect of heating on the microstructural evolution of La Peyratte granite deduced from acoustic velocity measurements. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2006, 243, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Q.; Huang, Y.H.; Tian, W.L.; Zhu, J.B. Erratum to: An experimental investigation on strength, deformation and crack evolution behavior of sandstone containing two oval flaws under uniaxial compression. Eng. Geol. 2017, 217, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockner, D. The Role of Acoustic-Emission in the Study of Rock Fracture. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1993, 30, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpalaskas, A.C.; Matikas, T.E.; Hemelrijck, D.V.; Papakitsos, G.S.; Aggelis, D.G. Acoustic emission monitoring of granite under bending and shear loading. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2016, 16, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, R.V.; Prasad, B.; Singh, R.K. Kaiser effect observation in reinforced concrete structures and its use for damage as-sessment-ScienceDirect. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2015, 15, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Nordlund, E. assessment of damage in rock using the kaiser effect of acoustic-emission. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1993, 30, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Zhang, R.; Xiong, H.; Zhao, D. Dynamic analysis of rockfall impact on a protective structure via FEM-DEM coupling. Nat. Hazards 2023, 119, 1771–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, H.; Moriguchi, S.; Tsuda, Y.; Yoshida, I.; Iwanaga, S.; Terada, K. A method for rockfall risk quantification and optimal arrangement of protection structures along a road. Eng. Geol. 2023, 314, 107004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Han, W.; Bao, H. A comprehensive approach for bridge performance evaluation under rockfall impact integrated with geological hazard analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 141, 106668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, J. Research on the penetration coefficient during the rock drilling process by cyclic impact. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 2175–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Weng, L.; Hou, P.; Chu, Z.; Yin, X.; Liang, Y.; Liu, Q. Revealing the impacts of fracture morphology and grouting parameter on the slurry diffusion behavior in rough rock fracture with flowing water: Insights from numerical modeling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2025, 195, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yue, Z.; Xu, S.; Gao, D.; Li, A.; Ren, M. Meso–macro-theoretical Analysis and Experimental Verification of Microwave-Assisted Breaking Rock Under Double-Indenter Impact. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 12069–12090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Density (g/cm3) | P-Wave Velocity (m/s) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Uniaxial Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 2.63 | 4957 | 45.37 | 102.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; He, C.; Fu, Z.; Zeng, J. Experimental Study of Micro/Macro Damage and Failure Mechanism of Granite Subjected to Different Impact Velocities and Numbers. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12758. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312758

Zhang P, Liu Y, Zhou Y, He C, Fu Z, Zeng J. Experimental Study of Micro/Macro Damage and Failure Mechanism of Granite Subjected to Different Impact Velocities and Numbers. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12758. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312758

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Penglin, Yang Liu, Yuan Zhou, Chunhui He, Zhiqian Fu, and Jianjun Zeng. 2025. "Experimental Study of Micro/Macro Damage and Failure Mechanism of Granite Subjected to Different Impact Velocities and Numbers" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12758. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312758

APA StyleZhang, P., Liu, Y., Zhou, Y., He, C., Fu, Z., & Zeng, J. (2025). Experimental Study of Micro/Macro Damage and Failure Mechanism of Granite Subjected to Different Impact Velocities and Numbers. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12758. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312758