3.2. Task Performance

3.2.1. Button Operation Efficiency

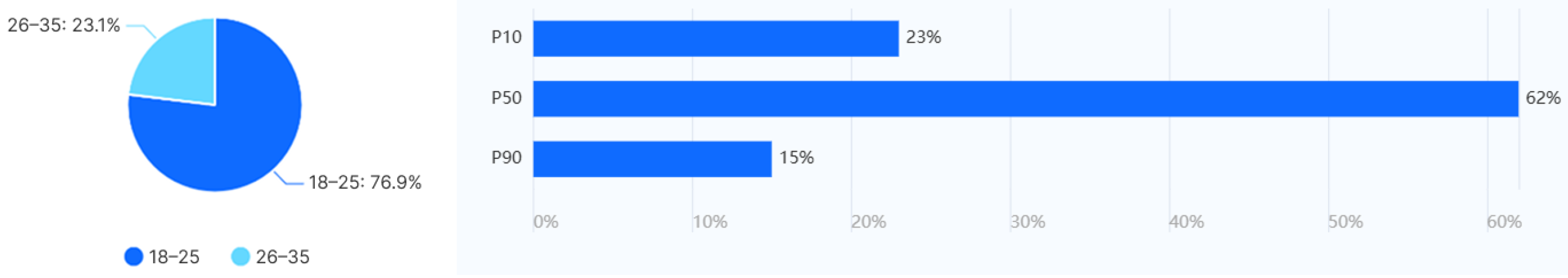

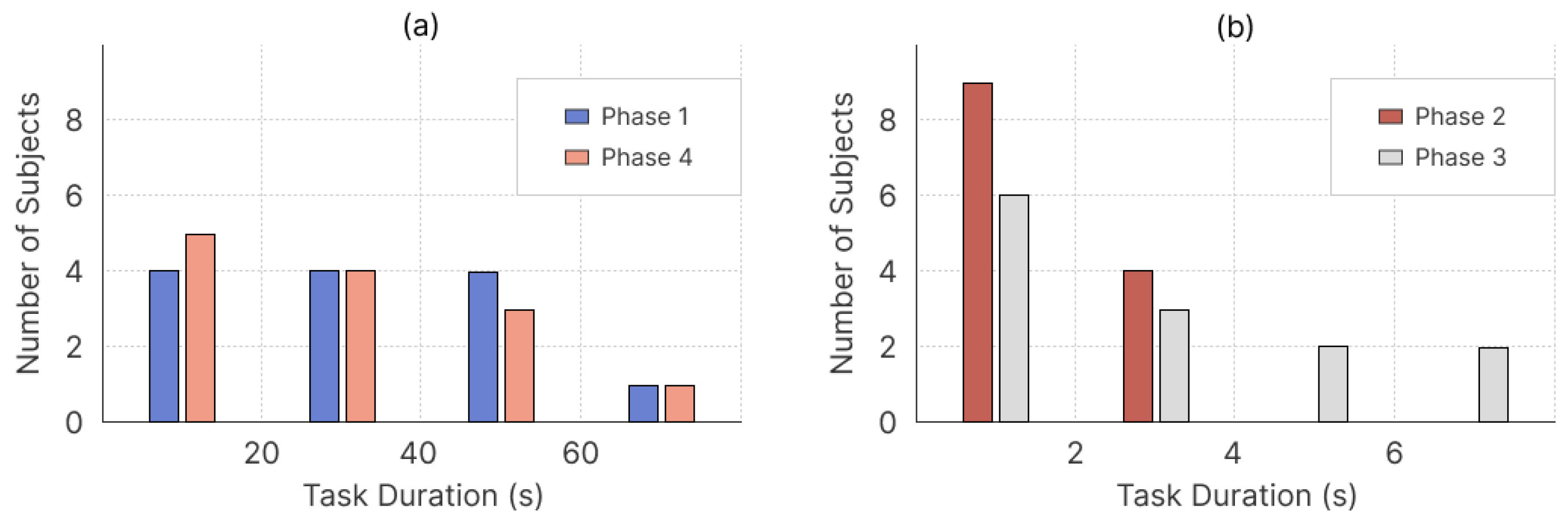

Button operation efficiency was checked by observing how long the task took in total (

Figure 7) and the gap between clicks on buttons (

Figure 8).

At the task level, the total operating time showed overall efficiency and complexity. The phases, including a simple single action, like Weapon and Trigger, had the quickest task lengths, as most participants took less than 2.5–4 s on these. In stark contrast, the TMS and CMS period phases that demanded bidirectional input were the ones that tended to have very long durations, with typical ranges between 20 and 60 s.

To further verify the significance of differences in total durations among various phases, statistical tests were performed on the data. First, the Shapiro–Wilk test for residuals showed p > 0.05, confirming the normality assumption was satisfied and thus the repeated-measures ANOVA results were credible. The sphericity test result indicated that the data did not meet the sphericity assumption ( = 39.405, df = 5, p < 0.001). Therefore, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was adopted ( = 0.552), and the corrected result showed that there were significant differences in the total durations among the 4 phases (F = 18.306, p < 0.001, = 0.604). The Bonferroni post hoc test results further revealed that Phase 1 had significant differences from both Phase 2 and Phase 3 (both p < 0.001) but no significant difference from Phase 4 (p = 1.000); Phase 4 also had significant differences from both Phase 2 and Phase 3 (both p ≤ 0.003) but no significant difference from Phase 1 (p = 1.000); there was no significant difference between Phase 2 and Phase 3 (p = 1.000), which was consistent with the characteristic in the descriptive statistics that phases with the same level of complexity exhibited similar time consumption.

At an act level, inter button operations check how locally efficient and motor skilled they are. The Weapon and Trigger buttons had a smaller and more compressed interval length, as their medians were 1.72 s and 1.86 s for both buttons. On the contrary, the directional commands such as CMS Up and TMS Down showed longer intervals, e.g., CMS Up: Median = 12.96 s, Mean = 19.05 s, skewed right, and reflected delayed hand re-positioning and spatial uncertainty.

To verify the validity of the statistical analysis, the Shapiro–Wilk test was first performed on residuals, and the result (p > 0.05) confirmed that the normality assumption was satisfied. A sphericity test was conducted to verify the validity of the statistical analysis, and the result indicated that the data met the sphericity assumption ( = 9.743, df = 5, p = 0.084 > 0.05). Bonferroni post hoc test results further revealed that Phase 1 had significant differences from both Phase 2 and Phase 3 (p = 0.009, p = 0.004, respectively) but no significant difference from Phase 4 (p = 1.000); Phase 4 also had significant differences from both Phase 2 and Phase 3 (p = 0.043, p = 0.049, respectively) but no significant difference from Phase 1 (p = 1.000); and there was no significant difference between Phase 2 and Phase 3 (p = 1.000).

3.2.2. Button Operation Accuracy

The accuracy and error rate per button task, as well as total number of attempts, are displayed in

Table 1. From the results, we can see that Weapon and Trigger operations attained very good accuracy rates of 92.9% and 86.7%, respectively, which also means having small error rates. Regarding the average number of attempts, the mean number of tries on these two tasks was just slightly over 1 (1.08 ± 0.27 and 1.15 ± 0.35).

On the contrary, for directional tasks with TMS and CMS buttons, accuracy was very low (56.5–72.2%), the error rate was very high, and they also needed somewhat more than the average number for these tasks. CMS Up had the lowest accuracy of all (56.5%), the most errors (43.5%), and also had the highest mean number of attempts (1.77 ± 0.58).

When performing the task of a single-button press (Weapon and Trigger), there was a high degree of consistency, but for the task involving multi-directionals (TMS and CMS), there was more variation and deviation in performance. It should be noted that statistical tests show that the accuracy rates at each stage do not vary significantly, and the results should be interpreted with caution.

3.4. Correlation Analysis

Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated on all operational phases of kinematic parameters (X variables) in relation to task-related parameters (Y variables). The following is the summary of the results and is illustrated in

Figure 13a–d. Given the potential inflation of Type I error risk caused by multiple pairwise correlation comparisons, the Benjamini–Hochberg (FDR) method was applied to adjust the statistical results, with the target false discovery rate set to

= 0.05. Detailed statistical inspection data can be found in

Appendix A,

Table A3. Correlation intensity classification criteria are as follows: weak correlation (0.1 ≤ r < 0.3), moderate correlation (0.3 ≤ r < 0.7), strong correlation (r ≥ 0.7). This study is exploratory. The correlation results are only used for descriptive analysis to preliminarily observe the association characteristics among variables. Given the methodological nature of exploratory research, this result does not constitute a definite conclusion and should be carefully interpreted and reasonably applied in combination with more empirical data.

- (1)

Phase 1—TMS Operation

In Phase 1, no statistically significant results were observed after correction, but there was an overall consistent and interpretable correlation trend.

The total task duration showed a moderate positive correlation with the movement distances of the hand, thumb, and index finger (r = 0.484–0.516), indicating that larger movement amplitudes are generally accompanied by longer task completion times. The interval between operations in the downward direction also showed a moderate positive correlation with movement distance (r = 0.440–0.478), suggesting that this direction may require more repositioning or fingertip adjustments. The variance in the thumb–index finger and thumb–middle finger distances showed a moderate positive correlation with total duration (r = 0.368–0.434), reflecting that when spatial control is less stable, participants are more likely to need additional fine-tuning movements, thereby prolonging the operation time. Speed-related variables showed a weak to moderate negative correlation with time indicators (r = −0.187 to −0.467), while the minimum distance from the thumb to TMS showed a moderate negative correlation (r = −0.478 to −0.549), indicating that faster movement speeds or closer finger positions may reduce completion time. In terms of accuracy, thumb speed showed a moderate positive correlation with accuracy (r = 0.411), while larger movement amplitudes and distance fluctuations showed a weak negative correlation (r = −0.160 to −0.271), indicating that stable finger spatial control may be associated with higher pressing reliability.

- (2)

Phase 2—Weapon Operation

Following Spearman correlation analysis and multiple comparison correction, Phase 2 showed a stable and partially significant correlation pattern.

The total task duration showed a moderate positive correlation (significant), with the movement distances of the hand and index finger (r = 0.681–0.687, p < 0.05), and a moderate positive correlation trend with the thumb movement distance (r = 0.659). The operation interval showed an almost consistent moderate positive correlation pattern with these three movement distance indicators, among which the relationships with the hand and index finger also reached a significant level (r = 0.692–0.698, p < 0.05). The variance in the thumb–index finger and thumb–middle finger distances both showed a moderate positive correlation with time indicators (r = 0.577–0.599), indicating that less stable control of finger distances may increase the need for compensatory fine-tuning movements. Among speed variables, the thumb approach speed showed a strong negative correlation (significant) with total duration and operation interval (r = −0.764 to −0.780, p < 0.05), indicating that a higher thumb approach speed can effectively shorten the operation execution time. In terms of accuracy, movement distance and distance variance both showed a moderate negative correlation trend (r = −0.401 to −0.445) but did not reach significance, and speed-related variables had almost no correlation with accuracy (r = 0.045–0.134).

- (3)

Phase 3—Trigger Operation

Following Spearman correlation analysis and multiple comparison correction, Phase 3 showed strong and consistent significant correlation characteristics.

The index finger approach speed showed an extremely strong positive correlation (significant) with total duration and operation interval (r = 0.967, p < 0.001), indicating that when participants approach the button at a faster speed, they are more likely to need additional correction movements after reaching it, resulting in a significant prolongation of the overall task time. The movement distances of the hand and thumb both showed a strong positive correlation (significant) with time indicators (r = 0.764–0.791, p < 0.05), while the index finger movement distance showed a moderate positive correlation trend (r = 0.462). In terms of accuracy, the index finger approach speed showed a moderate negative correlation (significant) with accuracy (r = −0.742, p < 0.05), indicating that a high-speed approach reduces pressing stability; the movement amplitudes of the thumb and hand showed a moderate negative correlation trend with accuracy (r = −0.536 to −0.577), and other spatial variables showed a weak correlation with accuracy (r = −0.124 to −0.289). These characteristics highlight that the efficiency of the Trigger button is highly related to dynamic approach control, especially emphasizing the importance of avoiding excessively fast approaches.

- (4)

Phase 4—CMS Operation

Phase 4 showed no statistically significant relationships but presented a stable trend similar to Phase 1.

The total task duration showed a moderate positive correlation trend with hand movement distance (r = 0.659), and a moderate negative correlation trend with thumb speed and the minimum thumb–button distance (r = −0.637 to −0.643), indicating that faster movements or closer initial hand positions may shorten the completion time. The right direction interval showed a moderate positive correlation trend with hand movement distance (r = 0.566) and a moderate negative correlation trend with thumb speed (r = −0.549). Several weak to moderate negative correlation trends were also observed for intervals in other directions (r = −0.407 to −0.593), reflecting differences in spatial adjustment requirements for different directions. Accuracy showed a moderate positive correlation trend with thumb speed and acceleration (r = 0.400–0.686), indicating that CMS operation may be more positively affected by rapid dynamic control, while overall spatial variables had a weak correlation with accuracy (r = −0.183 to 0.309).

3.5. Subjective Questionnaire Results

The survey questionnaires of 13 people were analyzed, and reliability and validity tests were carried out. Regarding Cronbach’s

coefficients, the overall Cronbach’s

coefficient was 0.810, showing that the scale had good internal reliability, meaning that the scales were effectively reflecting users’ perception of usability, experience, and workload (

Table 2).

3.5.1. System Usability and User Experience Evaluation

The data met normal distribution assumptions, and Mauchly’s test of sphericity was satisfied ( = 49.305, df = 44, p = 0.371). A repeated-measures ANOVA further revealed differences across evaluation dimensions (F = 3.963, p < 0.001). Bonferroni-adjusted comparisons indicated that design innovation was rated significantly higher than natural interaction (p = 0.04) and operation satisfaction (p = 0.01), while other dimension pairs showed no significant differences. These results suggest that the evaluative structure is consistent overall, but users perceived design innovativeness as a particularly strong aspect.

Ease of use (Q4): The operational intuitiveness had a mean of 4.1, with 77% giving positive ratings. The average score for the timeliness of the system’s feedback was similarly high, at 4.1, with 92.3% agreeing on it being effective. The virtual HOTAS system showed great usability;

Efficiency and performance (Q5): The mean score on the measure of button localization efficiency was 3.5 (moderate to high) with room for improvement. System response speed got an average score of 3.8, with 61.6% of people saying good things about it;

Comfort and operational experience (Q6): Both sub-items were rated the same way, with an average score of 3.7. Most people were okay with being able to use it comfortably, but a few noticed they got tired from using their hands, so there could be more work on making it less tiring to hold and use over a long time;

Stimulation and novelty (Q7): The system’s excitement dimension earned a mean result of 4.2 points, whereas design innovativeness attained its highest score of 4.6 points. These data imply that users hold rather positive views regarding the excitement and novelty the system can create;

Overall satisfaction and recommendation (Q8): The overall satisfaction score was 3.9, and the willingness to recommend score was 4.2. This suggests that there is a consistent positive rating, indicating that users can accept and disseminate it (

Table 3).

3.5.2. Task Load and Performance Evaluation

The task load questionnaire showed good data characteristics, with normality satisfied and sphericity upheld ( = 11.858, df = 9, p = 0.004). A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed differences across the load dimensions (F = 4.474, p = 0.004). Bonferroni-adjusted comparisons indicated that mental demands were rated significantly higher than physical demands (p = 0.008), while other pairs showed no significant differences. This suggests that the virtual HOTAS task imposed a relatively higher cognitive load than physical load, which is typical of spatially guided fine-motor tasks.

Task demands (Q9–Q11): Attention demands were given a mean score of 3.2, which is of a rather higher order. Physical demand obtained 2.4 points, which means the effort was pretty low. Time pressure scored 2.8, which is an average low sense of urgency. The system kept a good balance between mental and physical workload. Overall, the system maintained a reasonable balance between mental and physical workload, consistent with the ANOVA findings.

Task performance and emotional feedback (Q12–Q13): When evaluating self-rated task completion, on average, 3.7 was reported, most participants indicated their performance met their expectations. The frustration level was scored at 2.5, which shows a low negative feeling (

Table 4).