Hot-Water Infusion as an Efficient and Sustainable Extraction Approach for Edible Flower Teas

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from EFTs by Hot-Water Infusion and Ethanol Extraction

2.2.1. Hot-Water Extraction

2.2.2. Ethanol Extraction

2.3. Comparative Evaluation of Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents in Hot-Water Infusion and Ethanol Extracts

2.3.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.3.2. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

2.4. Determination Antioxidant Activity

2.4.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity Assay

2.4.2. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity Assay

2.4.3. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

2.5. Identification of Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids by UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS

2.6. Identification of Volatile Organic Compounds by HS-SPME/GC-MS

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Extraction Efficiency Between Hot-Water Infusion and 80% Ethanol Extracts

3.2. Comparison of Antioxidant Activity Between Hot-Water Extracts and 80% Ethanol Extracts

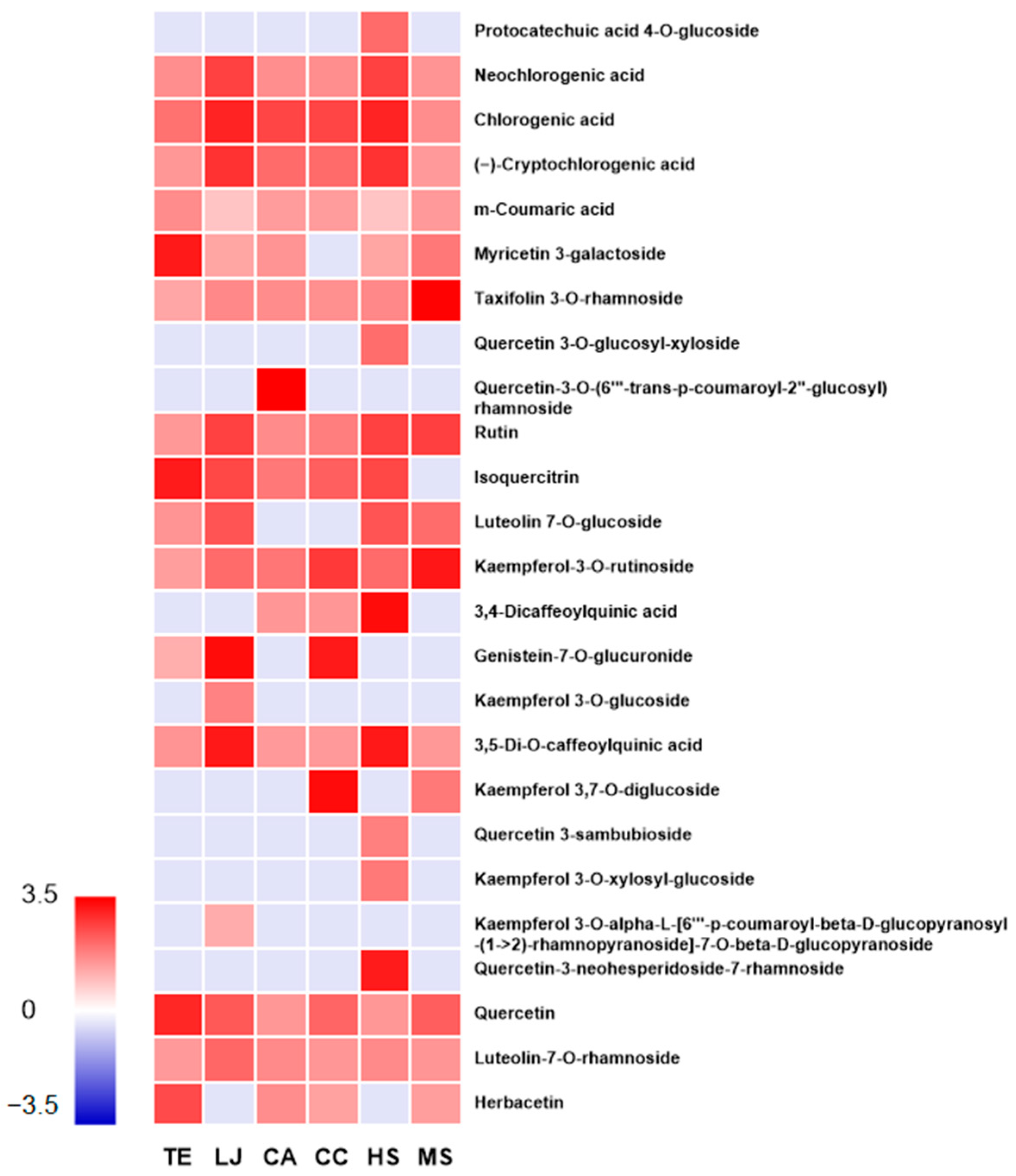

3.3. Identification of Phenolic Compounds in Hot-Water Extracts of EFTs

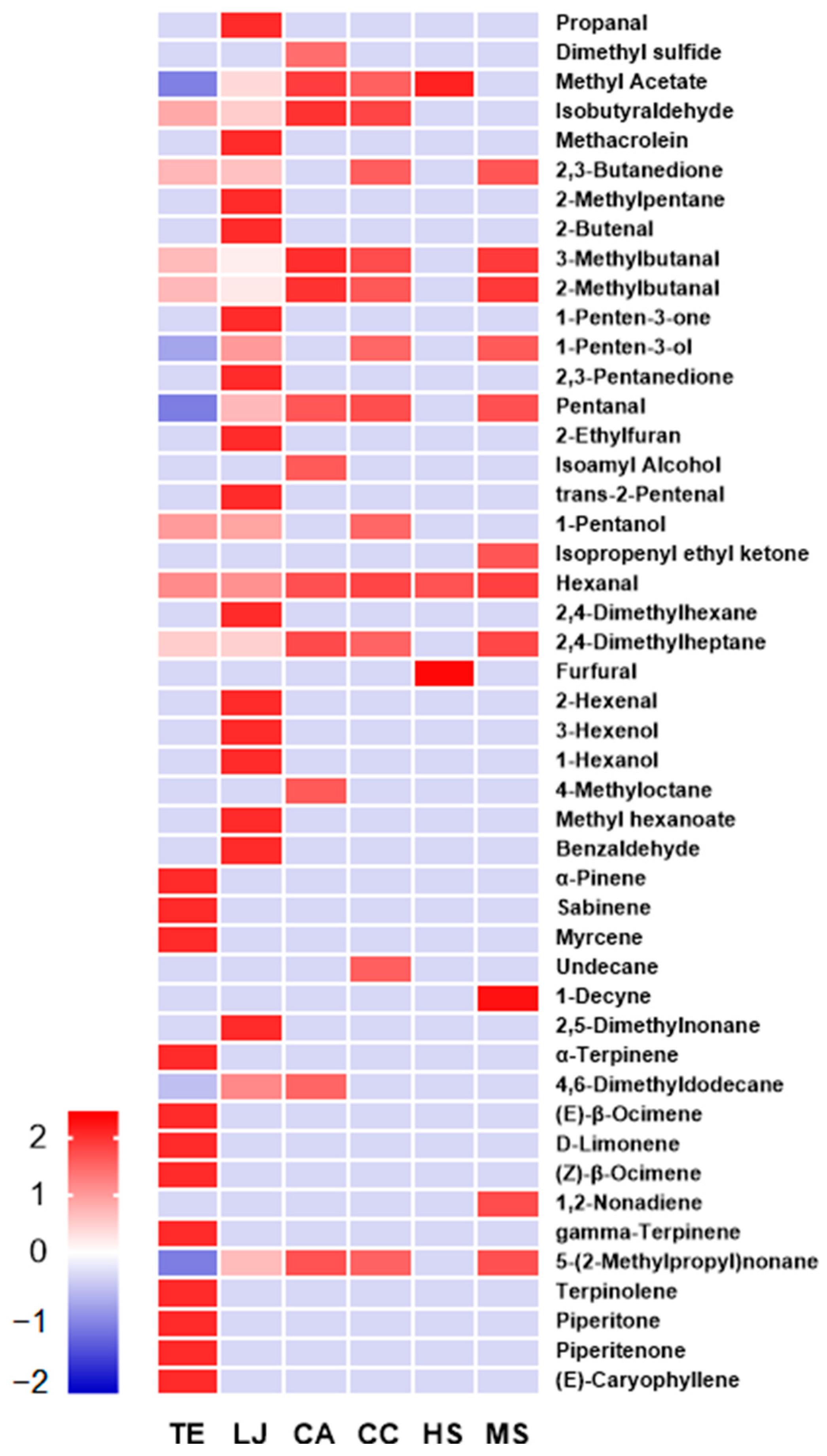

3.4. Identification of Volatile Organic Compounds in Hot-Water Extracts of EFTs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nhu-Trang, T.-T.; Nguyen, Q.-D.; Cong-Hau, N.; Anh-Dao, L.-T.; Behra, P. Characteristics and relationships between total polyphenol and flavonoid contents, antioxidant capacities, and the content of caffeine, gallic acid, and major catechins in wild/ancient and cultivated teas in Vietnam. Molecules 2023, 28, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N.; Mukhtar, H. Tea polyphenols for health promotion. Life Sci. 2007, 81, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Meenu, M.; Xu, B. A systematic investigation on free phenolic acids and flavonoids profiles of commonly consumed edible flowers in China. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 172, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.; Casal, S.; Pereira, J.A.; Saraiva, J.A.; Ramalhosa, E. An overview on the market of edible flowers. Food Rev. Int. 2020, 36, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.; Tao, W.; Fernandes, A.; Faria, A.; Ferreira, I.M.; He, J.; de Freitas, V.; Mateus, N.; Oliveira, H. Anthocyanin-rich edible flowers, current understanding of a potential new trend in dietary patterns. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Książkiewicz, M.; Karczewska, M.; Nawrot, F.; Korybalska, K.; Studzińska-Sroka, E. Traditionally Used Edible Flowers as a Source of Neuroactive, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Extracts and Bioactive Compounds: A Narrative Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoddami, A.; Wilkes, M.A.; Roberts, T.H. Techniques for analysis of plant phenolic compounds. Molecules 2013, 18, 2328–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caser, M.; Scariot, V. The contribution of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by petals and pollen to the scent of garden roses. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janarny, G.; Gunathilake, K.D.P.P.; Ranaweera, K.K.D.S. Nutraceutical potential of dietary phytochemicals in edible flowers—A review. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dujmović, M.; Radman, S.; Opačić, N.; Fabek Uher, S.; Mikuličin, V.; Voća, S.; Šic Žlabur, J. Edible flower species as a promising source of specialized metabolites. Plants 2022, 11, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, J.O.; De Souza, M.C.; Da Silva, L.C.; Lachos-Perez, D.; Torres-Mayanga, P.C.; Machado, A.P.d.F.; Forster-Carneiro, T.; Vázquez-Espinosa, M.; González-de-Peredo, A.V.; Barbero, G.F. Extraction of flavonoids from natural sources using modern techniques. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 507887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, K.; Shahbaz, H.M.; Kwon, J.H. Green extraction methods for polyphenols from plant matrices and their byproducts: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, R.; Barbosa, A.; Advinha, B.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J. Green extraction techniques of bioactive compounds: A state-of-the-art review. Processes 2023, 11, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lian, X.; Ye, C.; Wang, L. Analysis of flower color variations at different developmental stages in two honeysuckle (Lonicera Japonica Thunb.) cultivars. HortScience 2019, 54, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, W.; Neli, D.; Rita, Z.; Edi, S. Study of Morphology, Nutrition and Bioactive Compounds at Two Accessions Marigold (Tagetes Erecta) in Kepahiang Regency. Int. J. 2024, 3, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xin, H.-l.; Guo, M.-l. Review on research of the phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Celosia argentea. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haratym, W.; Weryszko-Chmielewska, E.; Konarska, A. Microstructural and histochemical analysis of aboveground organs of Centaurea cyanus used in herbal medicine. Protoplasma 2020, 257, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da-Costa-Rocha, I.; Bonnlaender, B.; Sievers, H.; Pischel, I.; Heinrich, M. Hibiscus sabdariffa L.–A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.-S.; Tene, S.T.; Teibo, J.O.; Shaheen, H.M.; Oluwatoba, O.S.; Teibo, T.K.A.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Garbee, A.I.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M. The phytochemical profiling, pharmacological activities, and safety of malva sylvestris: A review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2023, 396, 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Update on natural food pigments-A mini-review on carotenoids, anthocyanins, and betalains. Food Res. Int. 2019, 124, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaskova, A.; Mlcek, J. New insights of the application of water or ethanol-water plant extract rich in active compounds in food. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1118761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, S.H.; Cao, L.; Jeong, S.J.; Kim, H.-R.; Nam, T.J.; Lee, S.G. The Comparison of Total Phenolics, Total Antioxidant, and Anti-Tyrosinase Activities of Korean Sargassum Species. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 6640789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amensour, M.; Sendra, E.; Abrini, J.; Bouhdid, S.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. Total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of myrtle (Myrtus communis) extracts. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2009, 4, 1934578X0900400616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goli, A.H.; Barzegar, M.; Sahari, M.A. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic compounds of pistachio (Pistachia vera) hull extracts. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suksathan, R.; Rachkeeree, A.; Puangpradab, R.; Kantadoung, K.; Sommano, S.R. Phytochemical and nutritional compositions and antioxidants properties of wild edible flowers as sources of new tea formulations. NFS J. 2021, 24, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiogiannis, D.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Athanasiadis, V.; Bozinou, E.; Makris, D.P.; Lalas, S.I. Successive solvent extraction of polyphenols and flavonoids from Cistus creticus L. leaves. Oxygen 2023, 3, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Gu, X.; TaNG, J. Extraction, purification, and characterisation of the flavonoids from Opuntia milpa alta skin. Czech J. Food Sci 2010, 28, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Li, W.; Feng, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, S.; Tan, Y.; Wu, L. The Dynamic Remodeling of Plant Cell Wall in Response to Heat Stress. Genes 2025, 16, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y.; Yoon, N.; Lee, Y.J.; Woo, K.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Lee, J.; Jeong, H.S. Influence of thermal processing on free and bound forms of phenolics and antioxidant capacity of rice hull (Oryza sativa L.). Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 25, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slámová, K.; Kapešová, J.; Valentová, K. “Sweet flavonoids”: Glycosidase-catalyzed modifications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, M.; Feng, T.; Tong, Y.; Zhuang, H.; Lo, C.; Sun, H.; Chen, L.; Song, S. Characterization of key aroma compounds and construction of flavor base module of Chinese sweet oranges. Molecules 2019, 24, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers IV, E.; Koppel, K. Associations of volatile compounds with sensory aroma and flavor: The complex nature of flavor. Molecules 2013, 18, 4887–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Tang, L.; Gao, X.; Han, X.; Liu, C.; Song, H. Study of Aroma Characteristics and Establishment of Flavor Molecular Labels in Fermented Milks from Different Fermentation Strains. Foods 2025, 14, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.A. Odour-active compounds in pineapple (Ananas comosus [L.] Merril cv. Red Spanish). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, B.; Shen, C.; Yu, L.; Gong, C.; Xu, Y.; Tang, K. Identification, quantitation and organoleptic contributions of furan compounds in brandy. Food Chem. 2023, 412, 135543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongsoongnern, P.; CHAMBERS IV, E. A lexicon for green odor or flavor and characteristics of chemicals associated with green. J. Sens. Stud. 2008, 23, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Code 2 | TPC (mg GAE/g dw) | TFC (mg QE/g dw) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot-Water | 80% Ethanol | Hot-Water | 80% Ethanol | |

| TE | 64.72 ± 0.71 a*** | 49.66 ± 4.60 a | 21.37 ± 1.46 a*** | 25.72 ± 1.06 a |

| LJ | 59.13 ± 1.02 b*** | 40.37 ± 0.58 b | 3.51 ± 0.85 b** | 2.28 ± 0.27 c |

| CA | 18.84 ± 0.92 cd*** | 8.07 ± 0.22 c | 2.14 ± 0.16 c*** | 4.19 ± 0.15 b |

| CC | 16.05 ± 1.24 d*** | 3.98 ± 0.11 e | 2.57 ± 0.42 bc*** | 0.96 ± 0.04 e |

| HS | 17.28 ± 5.41 d*** | 7.95 ± 0.16 c | 2.42 ± 0.52 c* | 1.80 ± 0.11 cd |

| MS | 22.12 ± 2.09 c*** | 6.69 ± 0.19 d | 1.54 ± 0.19 c | 1.54 ± 0.06 de |

| Sample Code 2 | ABTS (mg VCE/g dw) | DPPH (mg VCE/g dw) | FRAP (μM FeSO4/g dw) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot-Water | 80% Ethanol | Hot-Water | 80% Ethanol | Hot-Water | 80% Ethanol | |

| TE | 101.41 ± 4.15 a* | 106.23 ± 3.48 a | 62.44 ± 4.73 b* | 57.08 ± 5.93 a | 1345.91 ± 118.43 a* | 1251.94 ± 54.01 a |

| LJ | 45.98 ± 2.13 b* | 49.11 ± 2.81 b | 66.56 ± 4.71 a*** | 22.80 ± 5.39 b | 812.91 ± 63.68 b*** | 553.17 ± 10.66 b |

| CA | 34.32 ± 5.30 c*** | 9.98 ± 0.43 c | 9.48 ± 0.42 c | 9.75 ± 1.04 cd | 174.72 ± 19.66 d | 176.70 ± 10.57 d |

| CC | 29.41 ± 4.67 c*** | 5.39 ± 0.14 d | 12.82 ± 1.18 c*** | 4.53 ± 0.51 e | 205.17 ± 44.86 d*** | 72.26 ± 6.20 e |

| HS | 32.17 ± 1.72 c*** | 10.51 ± 0.91 c | 12.97 ± 1.52 c | 12.95 ± 0.83 c | 396.81 ± 27.27 c*** | 265.27 ± 10.21 c |

| MS | 24.37 ± 1.25 d*** | 8.39 ± 0.44 c | 9.06 ± 0.79 c*** | 6.70 ± 0.32 de | 198.54 ± 29.20 d*** | 102.24 ± 5.14 e |

| TPC | TFC | ABTS | DPPH | FRAP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | 1 | 0.67 * | 0.86 * | 0.93 * | 0.91 * |

| TFC | - | 1 | 0.91 * | 0.72 * | 0.89 * |

| ABTS | - | - | 1 | 0.82 * | 0.95 * |

| DPPH | - | - | - | 1 | 0.92 * |

| FRAP | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Proposed Compounds | RT (min) | Mode | m/z | Major Fragments | Formula | Classification | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocatechuic acid 4-O-glucoside | 3.87 | [M-H]¯ | 315.07 | 141, 185 | C13H16O9 | Phenolic acid | HS |

| Neochlorogenic acid | 4.43 | [M-H]¯ | 353.09 | 191, 135, 179 | C16H18O9 | Phenolic acid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| Chlorogenic acid | 5.04 | [M-H]¯ | 353.09 | 191, 133, 215 | C16H18O9 | Phenolic acid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| (−)-Cryptochlorogenic acid | 5.21 | [M-H]¯ | 353.09 | 173, 135, 179 | C16H18O9 | Phenolic acid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| m-Coumaric acid | 5.26 | [M-H]¯ | 163.04 | 119, 145, 117 | C9H8O3 | Phenolic acid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| Myricetin 3-galactoside | 6.22 | [M-H]¯ | 479.08 | 317, 316, 315 | C21H20O13 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, CA, HS, and MS |

| Taxifolin 3-O-rhamnoside | 6.31 | [M-H]¯ | 449.11 | 259, 287, 121 | C21H22O11 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| Quercetin 3-O-glucosyl-xyloside | 6.34 | [M-H]¯ | 595.13 | 371, 597, 335 | C26H28O16 | Flavonoid | HS |

| Quercetin 3-O-(6′″-trans-p-coumaroyl-2″-glucosyl)rhamnoside | 6.35 | [M-H]¯ | 755.2 | 284, 300, 255 | C21H20O12 | Flavonoid | CA |

| Rutin | 6.64 | [M-H]¯ | 609.15 | 300, 271, 255 | C27H30O16 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| Isoquercitrin | 6.9 | [M-H]¯ | 463.09 | 301, 285, 271 | C21H20O12 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, and HS |

| Luteolin 7-O-glucoside | 6.97 | [M-H]¯ | 447.09 | 285, 113 | C21H20O11 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, HS, and MS |

| Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside | 7.16 | [M-H]¯ | 593.15 | 285, 284, 255 | C27H30O15 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| 3,4-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | 7.38 | [M-H]¯ | 515.12 | 353, 179, 135 | C25H24O12 | Phenolic acid | CA, CC, and HS |

| Genistein 7-O-glucuronide | 7.66 | [M-H]¯ | 445.09 | 269, 268, 431 | C21H18O11 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, and CC |

| Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | 7.4 | [M-H]¯ | 447.09 | 191, 255, 255 | C21H20O11 | Flavonoid | LJ |

| 3,5-Di-O-caffeoylquinic acid | 7.71 | [M-H]¯ | 515.12 | 353, 179, 135 | C25H24O12 | Phenolic acid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| Kaempferol 3,7-O-diglucoside | 4.23 | [M+H]+ | 611.16 | 287, 449, 137 | C57H110O16Si10 | Flavonoid | CC and MS |

| Quercetin 3-sambubioside | 4.56 | [M+H]+ | 597.14 | 303, 301 | C26H28O16 | Flavonoid | HS |

| Kaempferol 3-O-xylosyl-glucoside | 4.96 | [M+H]+ | 581.15 | 287, 549, 137 | C15H10O6 | Flavonoid | HS |

| Kaempferol 3-O-α-L-[6′″-p-coumaroyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-rhamnopyranoside]-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | 5.96 | [M+H]+ | 903 | 271, 287, 609 | C42H46O22 | Flavonoid | LJ |

| Quercetin 3-neohesperidoside-7-rhamnoside | 6.34 | [M+H]+ | 757.22 | 287, 303, 153 | C33H40O20 | Flavonoid | CA |

| Quercetin | 6.87 | [M+H]+ | 303.05 | 273, 153, 121 | C15H10O7 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| Luteolin 7-O-rhamnoside | 6.92 | [M+H]+ | 595.16 | 287, 449, 117 | C27H30O15 | Flavonoid | TE, LJ, CA, CC, HS, and MS |

| Herbacetin | 8.41 | [M+H]+ | 303.05 | 169, 121 | C15H10O7 | Flavonoid | TE, CA, CC, and MS |

| Sample Code 1 | RT (min) | m/z (Major Fragment Ion) | Formula | Classification | Proposed Compounds | Odor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE | 7.21 | 72, 40, 41 | C4H8O | Aldehyde | Isobutyraldehyde | pungent |

| 8.33 | 86, 43, 42 | C4H6O2 | Ketone | 2,3-Butanedione | butter | |

| 12.37 | 86, 44, 41 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | 3-Methylbutanal | fruity | |

| 12.99 | 96, 57, 41 | C5H12O | Aldehyde | 2-Methylbutanal | sweet | |

| 18.39 | 88, 42, 55 | C5H12O | Alcohol | 1-Pentanol | sweet | |

| 19.50 | 100, 44, 56 | C6H12O | Aldehyde | Hexanal | green grass | |

| 21.35 | 128, 43, 85 | C9H20 | Alkane | 2,4-Dimethylheptane | pungent | |

| 26.23 | 136, 93, 91 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | α-pinene | woody | |

| 28.00 | 136, 93, 77 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | Sabinene | citrus; woody | |

| 28.54 | 136, 93, 41 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | Myrcene | floral | |

| 30.55 | 136, 121, 93 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | α-terpinene | woody; mint | |

| 31.21 | 136, 93, 91 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | (E)-β-Ocimene | green grass | |

| 31.37 | 136, 68, 93 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | D-Limonene | citrus | |

| 31.93 | 136, 93, 91 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | (Z)-β-ocimene | green grass | |

| 32.80 | 136, 93, 121 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | gamma-Terpinene | woody | |

| 34.21 | 136, 93, 121 | C10H16 | Monoterpene | Terpinolene | woody | |

| 39.88 | 152, 82, 110 | C10H16O | Monoterpene ketone | Piperitone | mint | |

| 43.37 | 150, 107, 91 | C10H14O | Monoterpene ketone | Piperitenone | mint | |

| 47.07 | 204, 93, 91 | C15H24 | Sesquiterpene | (E)-Caryophyllene | spicy | |

| LJ | 5.35 | 58, 29, 28 | C3H6O | Aldehyde | Propanal | fruity |

| 6.41 | 74, 73, 42 | C3H6O2 | Ester | Methyl Acetate | fruity | |

| 7.22 | 72, 40, 41 | C4H8O | Aldehyde | Isobutyraldehyde | pungent | |

| 7.66 | 70, 41, 39 | C4H6O | Aldehyde | Methacrolein | pungent | |

| 8.35 | 86, 43, 42 | C4H6O2 | Ketone | 2,3-Butanedione | butter | |

| 8.47 | 86, 43, 42 | C6H14 | Alkane | 2-Methylpentane | gasoline | |

| 11.69 | 70, 41, 39 | C4H6O | Aldehyde | 2-Butenal | alcoholic | |

| 12.38 | 86, 44, 41 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | 3-Methylbutanal | fruity | |

| 12.99 | 96, 57, 41 | C5H12O | Aldehyde | 2-Methylbutanal | sweet | |

| 14.06 | 84, 56, 27 | C5H8O | Ketone | 1-Penten-3-one | spicy; pungent | |

| 14.32 | 86, 57, 29 | C5H10O | Alcohol | 1-Penten-3-ol | burnt; butter | |

| 14.55 | 100, 43, 29 | C5H8O2 | Ketone | 2,3-Pentanedione | butter | |

| 14.65 | 86, 44, 29 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | Pentanal | green grass; fruity; pungent | |

| 15.49 | 96, 81, 53 | C6H8O | Heterocyclic aromatic compound | 2-Ethylfuran | pungent; burnt | |

| 17.31 | 84, 55, 83 | C5H8O | Aldehyde | trans-2-Pentenal | fruity | |

| 18.41 | 88, 42, 55 | C5H12O | Alcohol | 1-Pentanol | sweet | |

| 19.50 | 100, 44, 56 | C6H12O | Aldehyde | Hexanal | green grass | |

| 20.43 | 184, 43, 85 | C13H28 | Alkane | 2,4-Dimethylhexane | citrus; green grass; woody | |

| 21.35 | 128, 43, 85 | C9H20 | Alkane | 2,4-Dimethylheptane | pungent | |

| 21.44 | 114, 41, 55 | C7H14O | Aldehyde | trans-2-Hexenal | almond | |

| 21.88 | 100, 67, 41 | C6H12O | Alcohol | 3-Hexenol | green grass | |

| 22.38 | 102, 56, 55 | C6H14O | Alcohol | 1-Hexanol | sweet; green grass | |

| 24.62 | 130, 74, 43 | C7H14O2 | Ester | Methyl hexanoate | fruity | |

| 26.05 | 106, 77, 105 | C7H6O | Aldehyde | Benzaldehyde | almond | |

| 30.56 | 204, 57, 43 | C12H25C | Alkane | 2,5-Dimethylnonane | citrus | |

| 31.09 | 184, 71, 43 | C13H28 | Alkane | 4,6-Dimethyldodecane | floral; sweet | |

| 33.11 | 184, 71, 57 | C13H28 | Alkane | 5-(2-Methylpropyl)nonane | gasoline | |

| CA | 6.23 | 94, 62, 47 | C2H6S | Sulfur compound | Dimethyl sulfide | sweet |

| 6.39 | 74, 73, 42 | C3H6O2 | Ester | Methyl Acetate | fruity | |

| 7.22 | 72, 40, 41 | C4H8O | Aldehyde | Isobutyraldehyde | pungent | |

| 12.38 | 86, 44, 41 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | 3-Methylbutanal | butter | |

| 13.00 | 96, 57, 41 | C5H12O | Aldehyde | 2-Methylbutanal | fruity | |

| 14.65 | 86, 44, 29 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | Pentanal | green grass; fruity; pungent | |

| 16.97 | 88, 55, 42 | C5H12O | Alcohol | Isoamyl Alcohol | alcoholic | |

| 19.50 | 100, 44, 56 | C6H12O | Aldehyde | Hexanal | green grass | |

| 21.36 | 128, 43, 85 | C9H20 | Alkane | 2,4-Dimethylheptane | pungent | |

| 22.95 | 128, 43, 85 | C9H20 | Alkane | 4-Methyloctane | pungent | |

| 31.09 | 142, 71, 57 | C10H22 | Alkane | 4,6-Dimethyldodecane | floral; sweet | |

| 33.12 | 184, 71, 57 | C13H28 | Alkane | 5-(2-Methylpropyl)nonane | gasoline | |

| CC | 6.40 | 74, 73, 42 | C3H6O2 | Ester | Methyl Acetate | fruity |

| 7.22 | 72, 40, 41 | C4H8O | Aldehyde | Isobutyraldehyde | pungent | |

| 8.34 | 86, 43, 42 | C4H6O2 | Ketone | 2,3-Butanedione | butter | |

| 12.38 | 86, 44, 41 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | 3-Methylbutanal | fruity | |

| 13.00 | 96, 57, 41 | C5H12O | Aldehyde | 2-Methylbutanal | sweet | |

| 14.33 | 86, 57, 29 | C5H10O | Alcohol | 1-Penten-3-ol | burnt; butter | |

| 14.65 | 86, 44, 29 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | Pentanal | green grass; fruity; pungent | |

| 18.41 | 88, 42, 55 | C5H12O | Alcohol | 1-Pentanol | sweet | |

| 19.50 | 100, 44, 56 | C6H12O | Aldehyde | Hexanal | green grass | |

| 21.36 | 128, 43, 85 | C9H20 | Alkane | 2,4-Dimethylheptane | pungent | |

| 29.50 | 156, 57, 43 | C11H24 | Alkane | Undecane | faint | |

| 33.12 | 184, 71, 57 | C13H28 | Alkane | 5-(2-Methylpropyl)nonane | gasoline | |

| HS | 6.38 | 74, 73, 42 | C3H6O2 | Ester | Methyl Acetate | fruity |

| 19.51 | 100, 44, 56 | C6H12O | Aldehyde | Hexanal | green grass | |

| 20.44 | 74, 73, 42 | C3H6O2 | Aldehyde | Furfural | sweet; almond | |

| MS | 8.35 | 86, 43, 42 | C4H6O2 | Ketone | 2,3-Butanedione | butter |

| 12.39 | 86, 44, 41 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | 3-Methylbutanal | fruity | |

| 13.00 | 96, 57, 41 | C5H12O | Aldehyde | 2-Methylbutanal | sweet | |

| 14.33 | 86, 57, 29 | C5H10O | Alcohol | 1-Penten-3-ol | burnt; butter | |

| 14.66 | 86, 44, 29 | C5H10O | Aldehyde | Pentanal | green grass; fruity; pungent | |

| 18.41 | 98, 69, 41 | C6H10O | Ketone | Isopropenyl ethyl ketone | pungent | |

| 19.51 | 100, 44, 56 | C6H12O | Aldehyde | Hexanal | green grass | |

| 21.36 | 128, 43, 85 | C9H20 | Alkane | 2,4-Dimethylheptane | pungent | |

| 30.23 | 138, 67, 81 | C10H18 | Alkyne | 1-Decyne | green grass; citrus | |

| 32.06 | 124, 54, 67 | C9H16 | Alkene | 1,2-Nonadiene | gasoline | |

| 33.13 | 184, 71, 57 | C13H28 | Alkane | 5-(2-Methylpropyl)nonane | gasoline |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, J.W.; Baek, S.; Zhang, L.; Bae, J.-E.; Lee, S.G. Hot-Water Infusion as an Efficient and Sustainable Extraction Approach for Edible Flower Teas. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12730. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312730

Choi JW, Baek S, Zhang L, Bae J-E, Lee SG. Hot-Water Infusion as an Efficient and Sustainable Extraction Approach for Edible Flower Teas. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12730. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312730

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Ji Won, Suhyeon Baek, Li Zhang, Ji-Eun Bae, and Sang Gil Lee. 2025. "Hot-Water Infusion as an Efficient and Sustainable Extraction Approach for Edible Flower Teas" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12730. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312730

APA StyleChoi, J. W., Baek, S., Zhang, L., Bae, J.-E., & Lee, S. G. (2025). Hot-Water Infusion as an Efficient and Sustainable Extraction Approach for Edible Flower Teas. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12730. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312730