1. Introduction

Physical activity (PA) during childhood plays a vital role in supporting healthy growth and development [

1,

2]. Regular participation contributes to cardiovascular and musculoskeletal fitness, enhances psychological well-being, and is linked with better cognitive performance and academic outcomes [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, global surveillance data indicate that approximately 81% of adolescents worldwide do not achieve the recommended 60 min of daily MVPA, with insufficient activity consistently observed across regions and income levels [

3]. In Croatia, only approximately 13% to 31% of children and adolescents meet this criterion, depending on age and sex, with boys being more likely than girls to reach the target [

4]. Moreover, PA levels also decline sharply with age, with the proportion of sufficiently active youth decreasing from approximately one-third at age 11 to less than one-fifth by age 15, reflecting trends observed internationally [

4].

In addition to insufficient levels of PA, the high prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity has become an important public health issue. Overweight in children is linked with cardiometabolic risk, impaired motor competence, musculoskeletal strain, and psychosocial difficulties [

5]. In Croatia, more than one-third of school-aged children are overweight or obese, placing the country among those with the highest prevalence rates in Europe [

6]. This is of particular concern because longitudinal evidence consistently shows that excess body weight acquired in youth strongly predicts adult obesity, cardiometabolic complications, and reduced overall health [

7,

8]. Low PA and excess weight often occur together, creating a cycle that limits motor development and reduces engagement in active lifestyles [

9].

The school environment, particularly physical education (PE), is crucial for promoting lifelong movement habits and overall health in children. Indeed, PE has been widely recognized as an important setting for increasing children’s PA levels and reducing the risk of being overweight and obese [

10,

11]. School-based PE offers structured opportunities for all pupils to engage in moderate-to-vigorous activities and can make a significant contribution to the achievement of daily activity recommendations [

12,

13]. Evidence from systematic reviews shows that high-quality PEs not only increase PA and fitness but can also have positive effects on body composition and health behaviors [

11,

14]. Not surprisingly, international bodies such as the World Health Organization identify PE as a cornerstone of comprehensive strategies to prevent childhood obesity and to support lifelong health [

15]. Although approaches differ across countries, research consistently highlights PE as one of the most effective school-based avenues for promoting healthy movement habits and counteracting global declines in PA among children [

16]. Increasing PE frequency provides additional structured opportunities to accumulate MVPA, which is associated with healthier weight trajectories in childhood [

13]. Moreover, regular participation in PE supports the development of motor competence, a factor that promotes higher PA engagement and reduces long-term obesity risk [

17,

18]. Together, these mechanisms explain how enhanced PE provision may influence both PA levels and body composition.

In Croatia, PE (specifically referred to as physical and health education) is a compulsory subject throughout primary school. Traditionally, grades 1–4 include three 45-min lessons per week delivered by generally educated teachers, whereas later students participate in two weekly lessons taught by specialized teachers (masters in PE/kinesiology). The Ministry of Science and Education of the Republic of Croatia, through its Action Plan 2024, set out guidelines for tackling obesity, with a particular focus on increasing PA [

19]. Among the proposed measures is the engagement of specialized PE teachers in grades 1–4. In line with this initiative, Croatia has introduced a national experimental schooling program, “Primary School as a Whole-Day School,” which commenced in the 2023–2024 school year in 64 selected Croatian primary schools as the first phase of a four-year pilot, with full-scale implementation planned upon completion and evaluation by 2027 [

20]. As a result of the problem of insufficient PA and alarming overweight in children, key changes include (i) increasing the frequency of PE in Grade 4 from two to three lessons per week (30% increase), (ii) appointing specialized PE teachers in Grade 1–4, (iii) introducing compulsory recreational breaks, and (iv) mandating that a significant proportion of extracurricular activities focus on physical activity, health, and sports domains [

20]. Collectively, these curricular reforms should provide a structured framework for increasing daily movement opportunities and supporting the development of PA and healthy body composition.

Extended school-day models and whole-school physical activity interventions implemented in several countries have shown that modifying the school schedule to include more structured and unstructured PA opportunities can increase children’s daily activity levels and improve selected health outcomes [

11,

21]. Programs such as the Finnish ‘Schools on the Move’ and UK active schools have demonstrated that integrating PA throughout the school day, through additional PE lessons, active recess, and extracurricular sport, can contribute to higher MVPA and may support healthy weight trajectories [

22,

23]. In Croatia, the “Primary School as a Whole-Day School” program follows a similar logic by extending instructional time and embedding more opportunities for movement, including increased PE frequency, specialist-led instruction, and daily recreational breaks. Despite the overall positive expectations, there is limited information on the effects of the experimental schooling program “Primary School as a Whole-Day School”. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has evaluated the effects of experimental schooling, showing promising effects of an experimental program on the acquisition of motor skills in early school-aged children [

24]. That study reported improvements in motor skill performance among children taught by specialist PE teachers; however, the study was short in duration (i.e., three months) and did not assess PA or body composition outcomes [

24]. Moreover, no study has examined the effects of experimental schooling programs on PA and body composition indices, which is particularly interesting given that targeting low PA and overweight/obesity are important objectives of the entire planned curricular reform. Therefore, the aim of this research was to evaluate the effects of the experimental program “Primary School as a Whole-Day School” on (i) PA and (ii) body composition indices in early school-aged children from southern Croatia over a period of one school year. To capture these outcomes comprehensively, PA was measured directly with accelerometers and evaluated subjectively via questionnaires. We hypothesized that the national experimental schooling program would result in (i) an increase in PA and (ii) favorable changes in body composition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

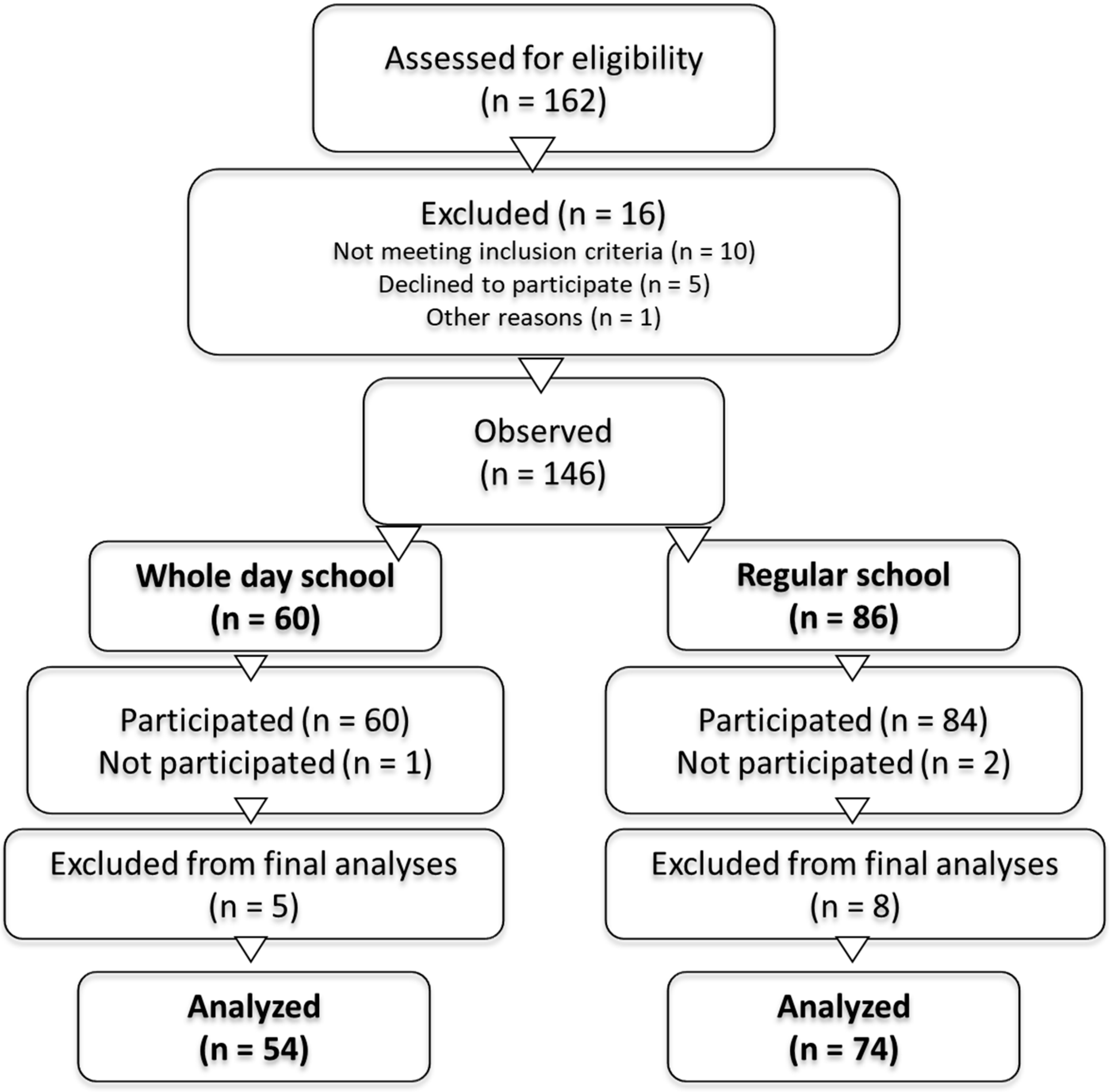

This study employed a natural experiment design with non-randomized group assignment to examine differences in outcomes between participants enrolled in two distinct types of schooling (whole-day schooling group and the regular schooling group), without any researcher-imposed intervention, as it evaluates the effects of a naturally occurring policy-driven exposure. The participants were 128 children aged 9–11 years (53 girls, 3rd-graders, and 4th-graders). The sample comprised 54 children (20 girls) who were involved in the whole-day-schooling program “Primary School as a Whole-Day School” and 74 same-age children who participated in the regular school program, 33 of whom were females. All 3rd- and 4th-graders from selected schools were invited to participate, and parental consent was obtained before the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Zagreb (approval number 93/2004, issued on 9 September 2024). The children involved in the study were healthy and regularly participated in the PE classes, while the great majority of them were involved in out-of-school sport programs during the course of this study (74% and 77% of the children in the experimental and control groups, respectively), with no significant difference between the study groups in out-of-school sport involvement. Inclusion criteria included: no health conditions that could prevent children from participating in PE classes, less than 20% absence from school over the study period, participation in the pre- and post-measurements, and parental consent for participation in the study. Exclusion criteria included health conditions that limited participation in PE, more than 20% school absences during the study period, and non-participation in pre- or post-testing. Initially, 140 children were tested at pre-testing, while post-testing involved 138 children. However, because of the non-meeting inclusion criteria and the necessity of pairing pre- and post-testing results, the final sample included 128 children (54 in the experimental and 74 in the control group). The flow diagram is presented in

Figure 1.

This study utilized a natural experiment design, as schools were assigned to the experimental program on the basis of governmental decisions rather than random allocation. Most specifically, the schools included in the experimental program were based on the results of the official call of the Croatian Government, particularly the Croatian Ministry of Science and Education, “Call for Expressions of Interest for Inclusion of Primary Schools in the Experimental Program “Primary School as a Whole-Day School”, beginning in August 2022 [

20]. The call was initiated under the Policy Framework as part of the national education reform under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, with the main objective of testing a whole-day school model before considering nationwide implementation. The planned duration was four years, starting from the 2023/2024 school year, with >60 primary schools selected across Croatia. Most importantly, the program features included (i) extended school hours until 5:00 p.m.; (ii) changes in daily scheduling; (iii) more time for practice, review, creative and extracurricular activities; and (iv) a focus on reading, STEM, sports, and arts. The teaching organization consisted of classes held in a single morning shift, with a minimum of 9 h of student presence in school, with morning blocks consisting of regular lessons, and afternoon blocks consisting of learning support, various activities (i.e., reading, STEM, sports, and arts), and leisure time. The target group was pupils from grades 1 through 8 in the selected schools. The selection criteria included geographic diversity, infrastructure readiness, motivation of school leaders and staff, and support from local communities. For the implementation of the program, the government provided various support for schools, including funding for additional staff (teachers, counselors), investments in equipment, space, and materials, and professional training for educators. The details about the most important differences between the standard school program and the National Experimental Program are presented in

Table 1.

It is also important to note that in regular school programs, PE classes for these age groups are generally taught by generally educated teachers (i.e., non-specialists). At the same time, the Whole Day School project provided salaries for specialized PE teachers who taught PE classes in the 1st to 4th grades, but some schools could not fulfill this requirement (please see later how it influenced the selection of schools in this study). In this study, we focused specifically on children who attended 3rd- and 4th-year primary schools in Split-Dalmatia County, the region of southern Croatia. Both the experimental and control groups consisted of children from schools with comparable environmental conditions, such as climates, available physical education resources, and socioeconomic contexts. This ensured that any observed effects could be attributed primarily to the experimental program rather than external differences. Since controlling for environmental effects on PA was highly important for the purpose of the study, we specifically selected one school for the experimental program and one similar school for the control program. Specifically, in the Split-Dalmatia county where the study was performed, only three schools were included in the Whole Day School project, of which one was located on the island with limited resources (no educated PE teacher, please see later for details on the program), and another one with <30 children involved in the program. Therefore, the observed experimental school was considered the most appropriate, both because of the geographical location and the number of participating children.

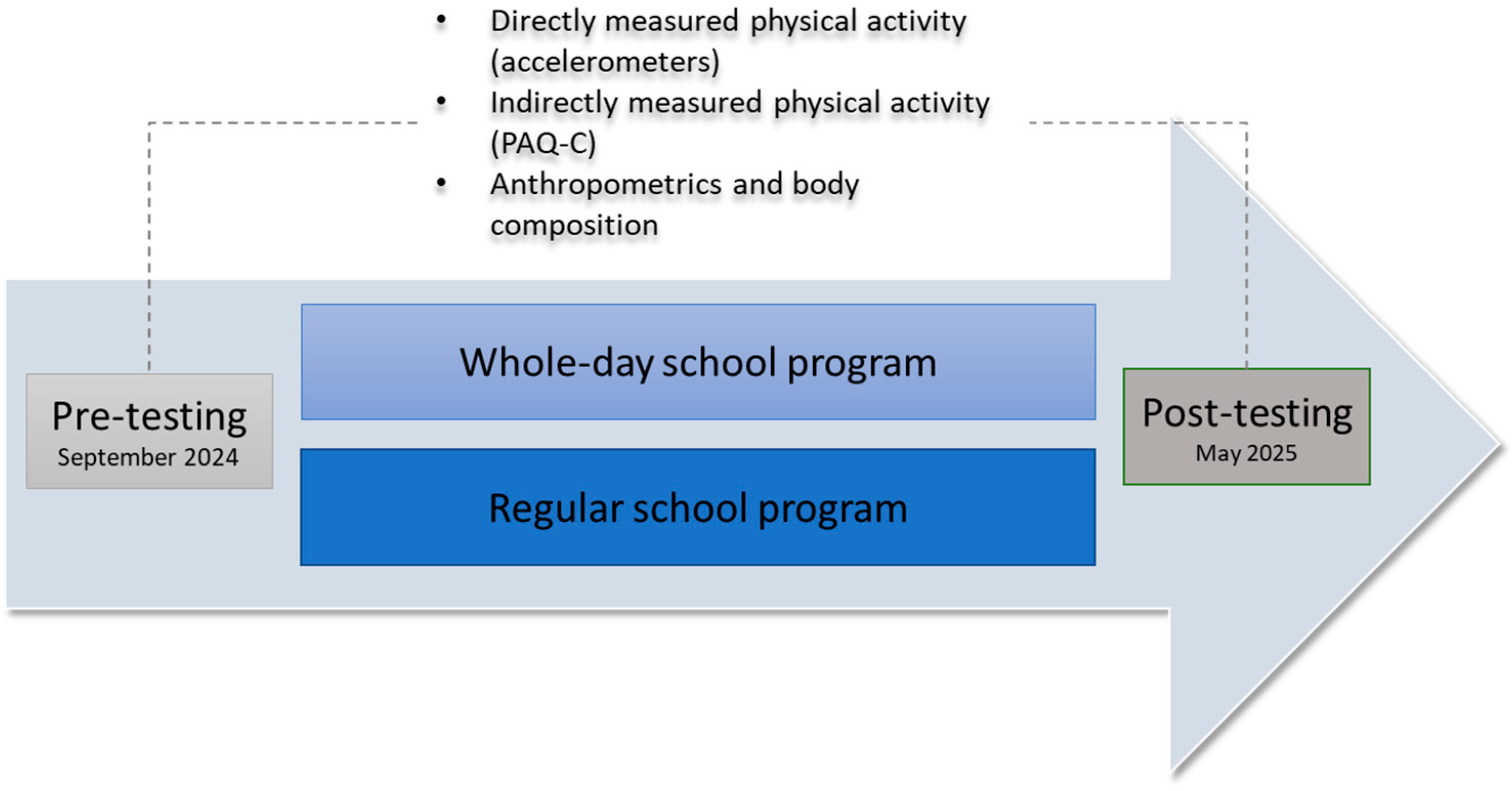

The design is presented in

Figure 2. The study was conducted over one school year, from September 2024 to May 2025, with pre-testing (pre-measurement) during the first three weeks of September and post-testing (post-measurement) during the last three weeks of May (for variables, please see the next subheading). Between the pre- and post-measurement, the whole-day schooling group participated in the experimental schooling program. In contrast, the second group participated in the regular schooling program (please see previously for differences in characteristics). In addition to those differences, children were not systematically monitored in their out-of-school activities, but since schools were from the same region and shared similar resources, the authors believe that eventual differences in out-of-school duties did not significantly influence the results of this investigation.

2.2. Intervention Description

The experimental ‘Primary School as a Whole-Day School’ program functioned as a whole-school intervention delivered continuously throughout one school year (September–May). Key PA-related components included:

(i) an increased frequency of PE lessons (three lessons per week in Grade 4),

(ii) delivery of all PE lessons by specialized PE teachers (kinesiologists) rather than generalist classroom teachers,

(iii) compulsory daily recreational breaks incorporating structured movement activities, and

(iv) mandatory participation in PA-oriented extracurricular sessions (sports, health-related activities).

Children in the whole-day schooling group were exposed to the program for the whole school year, with all activities embedded in the daily schedule. Although individual PE lesson attendance and fidelity of implementation were not monitored at the participant level, which represents a limitation of this study, all participating schools followed the officially mandated program requirements. The regular schooling group participated in the standard national curriculum, which included 2–3 PE lessons per week taught by generalist teachers and without compulsory recreational or extracurricular PA components.

2.3. Variables

In addition to grouping participants into whole-day schooling groups and the regular schooling groups, we observed sex (male vs. female; on the basis of school records), age (in years; on the basis of school records), PA (direct measurement and indirect evaluation), and anthropometric/body composition variables.

The PA was directly assessed via GENEActiv accelerometers (Activinsights Ltd., Cambridge, UK). This triaxial device, equipped with a seismic acceleration sensor, is small in size (36 × 30 × 12 mm), lightweight (16 g), waterproof, and additionally records body temperature, which supports the validation of energy expenditure and identification of nonwear time. GENEActiv is widely recognized for its use in monitoring physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep patterns [

25,

26]. The participants were instructed to wear the accelerometer continuously on their nondominant wrist for 24 h a day. The data collected by the devices were downloaded via GENEActiv PC software version 2.2 in raw format (.bin files) and subsequently processed via the R package GGIR version 1.2--0 [

27]. The analysis provided information on the duration of sedentary behavior, as well as time spent in light, moderate, and vigorous physical activity. The main variables of interest included the number of steps (STEPS), sedentary time (sedentary behavior—SB), light physical activity (LPA), moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), and vigorous physical activity (VPA). GENEActiv devices record raw triaxial acceleration continuously; therefore, no predefined epoch length was applied. Data were processed using the GGIR package, which automatically identifies non-wear periods and applies established.

GENEActiv-specific thresholds for classifying activity intensities. Participants with detected non-wear time were excluded from the analyses. A minimum of four valid days (≥2 weekdays and ≥2 weekend days) was required for inclusion, consistent with recommended procedures for assessing habitual PA in children. Intensity metrics (LPA, MVPA, VPA) were generated directly by the GGIR algorithm, which calculates activity categories from raw acceleration without requiring user-defined cut-points.

The Croatian version of the PAQ-C, a questionnaire designed to evaluate physical activity levels (PALs) in children aged 8–14, was used to indirectly measure PA [

28]. The PAQ-C includes 9 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, addressing different dimensions of activity participation. Example questions include “In the past 7 days, what did you usually do during a long break (excluding eating a snack)?” and “In the past 7 days, during your physical education (PE) classes, how often were you very active (e.g., playing intensely, running, jumping, throwing)?” The final PAQ-C score is calculated as the mean of all the responses, where a maximum score of 5 reflects a high level of physical activity, and a score of 1 reflects very low or no activity. The questionnaire is widely used in this region as a reliable and valid tool for the indirect evaluation of PA in school-aged children [

29]. The PAQ-C was included as a complementary measure to accelerometry in order to capture contextual and self-perceived aspects of children’s PA that are not fully reflected in device-based metrics. Additionally, its use allowed partial triangulation with accelerometer-derived outcomes, enabling us to examine whether subjective increases in PA corresponded with objectively measured changes in MVPA.

All participants underwent anthropometric/body composition assessment. Measurements were taken in the morning, at least three hours after waking up, and following food and fluid intake. Body height was measured with a Seca stadiometer (Seca, Birmingham, UK). Body mass and body composition were determined via a bioimpedance device (Tanita TBF-300, Tanita, Tokyo, Japan) following established guidelines for bioelectrical impedance analysis. The device was adjusted to correct for clothing weight (0.2 kg), after which the participants’ age, sex, and height were entered. During the assessment, the participants stood barefoot on the platform and placed their hands on the designated electrodes. The method estimates body composition on the basis of tissue conductivity, which varies owing to differences in water content. The variables obtained included body mass (kg), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), fat mass (FM, in % of body mass), and skeletal muscle mass (SMM, in % of body mass). All measurements for both groups were identical; they took place within school facilities and were conducted by trained kinesiologists. The same measurement protocols, staff, and devices were used at both time points to ensure measurement reliability.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All variables were examined for normality of distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Descriptive statistics were computed and are reported as means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (e.g., gender and grade).

Differences between pre- and post-measurement for the total sample were evidenced by a t-test for dependent samples. A 2 × 2 × 2 mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine the effects of time (pre- and post-measurement; within-subjects factor), group (experimental vs. control), and gender (male vs. female; both between-subjects factors) on each dependent variable. The assumption of homogeneity of covariance matrices was tested using Box’s M test, and equality of error variances was assessed via Levene’s test. Cell sizes were reviewed for approximate balance across conditions.

Effect sizes (ES) were reported using partial eta squared (η2) for ANOVA main and interaction effects, and interpreted as follows: η2 = 0.01–0.06 (small effect), η2 = 0.061–0.14 (medium effect), and η2 ≥ 0.141 (large effect). For significant effects, post hoc comparisons were conducted using Scheffé’s test, and Cohen’s d was reported to quantify the magnitude of pairwise differences.

Each dependent variable was analyzed separately using univariate ANOVAs. To control for potential inflation of Type I error due to multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was applied across tests.

All analyses were performed using Statistica v14.5 (TIBCO Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics for the total sample of participants at pre- and post-testing are presented in

Table 2.

The results of the multifactorial ANOVA are shown in

Table 3. Significant main effects for the factor “Group” (experimental vs. control) were found for BH (F test = 19.92,

p < 0.05). When “Gender” was observed as an ANOVA main effect, appropriate statistical significance was observed for SMM (F test = 12.11,

p < 0.05), PAQ-C score (F test = 14.51,

p < 0.05), STEPS (F test = 12.99,

p < 0.05), and VPA (F test = 35.58,

p < 0.05). For the main effect “Time” (pre- vs. post-measurement), statistically significant effects were found for BH (F test = 944,

p < 0.05), BM (F test = 22.80,

p < 0.05), BMI (F test = 5.15,

p < 0.05), and the PAQ-C score (F test = 8.57,

p < 0.05). The time × group interaction effects were significant for the PAQ-C (F test = 4.45,

p < 0.05) and MVPA (F test = 4.87,

p < 0.05) scores. When the time × gender interaction was analyzed, the effects were significant for BH (F test = 8.04,

p < 0.05). Finally, the time × group × gender effect was significant for STEPS (F test = 5.32,

p < 0.05) and MVPA (F test = 4.71,

p < 0.05). It has to be noted that although a significant Time × Group × Gender interaction was observed for STEPS, it did not reveal a clear intervention-related pattern and was therefore not further interpreted.

When the total sample of participants (not divided into boys and girls) was analyzed, post hoc differences were significant for body height and body mass, with an evident increase for both study groups. The PAQ-C increased significantly only in the experimental group. Notably, MVPA in the control group decreased, whereas it increased in the experimental group, with no significant post hoc differences within or between groups. With respect to between-group differences, the control group was taller and heavier than the experimental group in both measurements (

Table 4).

Among boys, significant between-group post hoc differences were found for BH and BM (with the control group being taller and heavier in both measurements). The among-group post hoc differences were significant for BH and BM (in both groups), as expected. The PAQ-C score significantly increased for the experimental boys only (

Table 5).

For girls, among the groups, post hoc differences were significant for body height in both study groups. Moreover, body mass and the PAQ-C score significantly increased only among the experimental girls. No significant between-group differences were found for girls (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

With respect to the study aims, several important findings exist. First, experimental schooling resulted in positive effects on directly measured PA, which was influenced mainly by changes that occurred among boys. Additionally, a significant effect of experimental schooling was found for indirectly measured PA. However, experimental schooling had no effect on body composition. Therefore, our first study hypothesis can be accepted, but the second study hypothesis should be rejected.

4.1. Positive Effects of the Experimental Schooling Program on Indices of Physical Activity

The main statistically significant finding of this study was that children involved in the experimental schooling program experienced positive changes in MVPA. Although the changes were not dramatic, it should be noted that the pre-measurement was performed at the beginning of the school year (September), when the weather conditions were far better than they were during the post-measurement (May). Together, these factors influence everyday behavior and, consequently, the PA of children [

30]. The first explanation for the positive effects of the experimental schooling program on PA is naturally related to the frequency of PE classes in the studied groups. The children involved in the experimental schooling program had a greater number of PE lessons than regular schooling, which could logically be transferred to their PAs. Similarly, earlier findings demonstrated that greater exposure to PE is associated with higher overall PA levels in school-aged children [

31,

32]. Second, it should be highlighted that PE lessons in the experimental program were taught by specialized PE teachers, whereas PE lessons in regular schooling were taught by generally educated teachers. Evidence from previous studies indicates that specialist-led PE tends to elicit higher activity levels and greater motor engagement than PE taught by generalist teachers, which may partly explain the observed differences [

24,

33]. Although we did not evaluate this problem specifically, and therefore, these considerations are to some extent hypothetical, it is well known that teacher instruction, lesson structure, and pedagogical approaches are important factors in promoting greater PA during PE classes [

10,

12]. While factors such as weather conditions and school workload toward the end of the academic year may influence habitual PA, these influences cannot be confirmed in our data and are therefore acknowledged as contextual limitations rather than explanatory mechanisms.

Irrespective of the discussed differences in PE lessons between study groups, another possible explanation also deserves attention. Specifically, the children in the experimental schools spent the entire day at school. Accordingly, they had extended opportunities for unstructured time outside of formal lessons (please see the main characteristics of the experimental program in the Methods section). The authors of the study reported that this time was often used for free play, which was both frequent and characterized by (at least) moderate intensity. Previous research has shown that unstructured play can contribute meaningfully to greater PA and serve as an important complement to structured PE [

34,

35]. Additionally, school-based intervention programs for promoting PA that emphasize an active lifestyle are particularly effective in fostering such environments [

36]. Taken together, the structured opportunities provided by additional PE lessons, specialized teachers, and the spontaneous opportunities afforded by free play during the school day may explain the greater MVPA observed in the experimental program. Our findings align with international evidence showing that whole-school and extended school-day models can positively influence children’s physical activity levels. Programs such as Finland’s Schools on the Move, the U.S. Comprehensive School Physical Activity Program (CSPAP), and Canadian whole-day activity initiatives have demonstrated that embedding structured and semi-structured PA opportunities throughout the school day can increase MVPA and attenuate typical declines in activity [

11,

17,

23].

In addition to the objectively measured increase in MVPA, a significant increase in the PAQ-C score among children participating in the experimental schooling program provides additional evidence of its positive impact on daily movement behavior. While self-reported measures such as the PAQ-C cannot capture activity intensity as precisely as accelerometers do, they offer valuable insights into how children perceive and experience their PA across different settings, including recess, organized sports, and informal play. The correspondence between higher PAQ-C scores and the observed increase in MVPA suggests that children involved in the experimental program not only accumulated more MVPA but also felt more active overall. This convergence of subjective and objective findings strengthens the conclusion that the whole-day school model meaningfully enhances both actual and perceived activity levels among participants [

10].

Interestingly, the PAQ-C score improved even though some objectively measured parameters, such as the STEPS, LPA, VPA, and SB, did not change significantly. This finding indicates that the PAQ-C may be more sensitive to shifts in motivation, engagement, and awareness of being active rather than capturing only the total quantity of movement. The experimental program, characterized by more frequent and specialist-led PE lessons, active breaks, and extended opportunities for unstructured play, likely fostered a more positive attitude toward PA and strengthened children’s self-perception as active individuals. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies, showing that interventions emphasizing supportive school environments and active learning contexts can increase self-reported PA even when objective measures show modest changes [

34,

35]. Therefore, the increase in PAQ-C scores observed in this study probably reflects not only behavioral engagement but also the psychosocial benefits of a school environment that values and promotes movement throughout the day.

The sex-specific analysis revealed that the changes in MVPA in boys actually led to overall greater MVPA in the experimental group. These findings are relatively understandable, mostly because of the gender specificity of the PE lessons. First, girls are often excluded or spared from physically demanding or energetically challenging exercises during PE lessons. Moreover, boys are more consistently exposed to these types of activities. Specifically, previous research has shown that PE lesson content and teacher expectations often differ by gender, which can influence the intensity of activity experienced in PE [

37,

38]. These gender-specific factors could naturally influence even the levels of MVPA achieved during PE classes in boys and girls in our study.

The second explanation relates to patterns of free activity during school hours in experimental schooling. As previously mentioned, the whole-day school model provided children with extended opportunities for unstructured play. However, being directly involved in the experiment, the authors witnessed that during free time, boys involved in the experimental program were more likely to engage in physically demanding activities such as running and competitive games. Moreover, girls tend to participate in less physically demanding forms of play, such as walking, discussing school duties, drawing, and doing homework, among others. Naturally, free play activities increase MVPA in boys but not in girls involved in experimental schooling. Although we are not able to definitively support our considerations via empirical evidence, we can support this by previous studies in which the authors highlighted that boys accumulate more intensive PA than girls do during recess and free play periods [

39,

40]. Together, these results suggest that both structured lesson content and unstructured play behaviors may have contributed to the observed differences between boys and girls in MVPA.

4.2. Lack of Effects of the Experimental Schooling Program on Body Composition Indices

Throughout the study period, no effects of experimental schooling on body composition were observed. There are two most likely explanations for these findings. The first one could be found in the relatively short study duration (e.g., one school year). In other words, it is likely that the greater MVPA achieved in the experimental program did not have an effect on body composition, since meaningful changes in body composition generally require sustained exposure to training stimuli over longer periods of time, often in combination with other lifestyle factors [

36]. The study period may therefore have been too brief to produce measurable changes. Importantly, the participants were in a phase of rapid growth and development, when maturational changes such as increases in height, body mass, and lean tissue occur at a pace that often masks or overrides the adaptations elicited by exercise stimuli [

41,

42]. This phenomenon makes it difficult to isolate the effects of PA interventions on body composition outcomes in this age group [

41].

Another explanation for the lack of differences in body composition between the study groups is related to the fact that experimental schooling did not include dietary interventions or nutritional strategies. Moreover, nutrition is a critical determinant of body composition, and even with higher levels of PA, unbalanced or inconsistent dietary intake can prevent measurable changes [

43]. The children observed herein most likely maintained their usual eating habits, which, together with other previously discussed factors, resulted in a lack of effect of experimental schooling on body composition. Although this study does not intend to question the quality and concept of experimental schooling, but rather aims to evaluate its effects on a preliminary basis, the general evidence from school-based interventions indicates that PA alone, although generally beneficial, may not be sufficient to alter body composition without nutritional support [

36]. For example, a six-month intervention providing 120 min of supervised physical exercise per week in addition to two hours of PE classes improved both anaerobic and aerobic fitness in lean and obese children, but no significant changes in body composition were observed [

44]. On the other hand, studies suggest that combined programs integrating PA and nutrition education are more effective in achieving improvements in body composition than activity-only approaches [

11,

45,

46].

A further consideration is the inherent limitation of bioimpedance analysis (BIA) in pediatric populations. BIA estimates are influenced by hydration status, recent food and fluid intake, and diurnal variation, all of which can alter conductivity and affect accuracy. These sources of variability may be amplified in growing children, potentially masking subtle changes in body composition despite standardized measurement procedures [

47]. Such measurement sensitivity should be considered when interpreting the absence of significant body composition effects.

4.3. Final Considerations

International frameworks emphasize the importance of schools as key settings for the promotion of PAs. The World Health Organization Global Action Plan on PA highlights whole-of-school approaches as effective strategies to increase PA levels among children and adolescents [

15,

48]. The experimental program evaluated in this research, designed as a whole-day school model, reflects these principles by creating multiple opportunities for movement across the school day, both during structured lessons and through unstructured free play. This approach is consistent with the recommendation that PA promotion should be integrated throughout the entire school day rather than restricted to PE classes alone [

49,

50]. However, although whole-of-school approaches are widely recommended, evidence on their implementation and effectiveness remains limited. Although our results do not provide a definitive conclusion on this topic, they contribute valuable preliminary evidence to the emerging body of literature.

From a practical perspective, these findings provide valuable insights for educational policy. The observed increases in MVPA suggest that school structures incorporating extended instructional time and specialist-led PE may enhance children’s daily activity levels within the existing curriculum. Such evidence supports policy initiatives aiming to expand the role of schools in promoting PA, particularly through increased PE provision and integrated movement opportunities throughout the school day. Implementing similar components more broadly may help address low PA levels in school-aged children at a population scale.

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

Several limitations should be considered before conclusions can be reached. First, and most importantly, the study followed a quasi-experimental design, and children were not randomly assigned to study groups but were instead placed in groups on the basis of external decisions (e.g., government policy). Second, the study was performed during a critical period of rapid growth and development, which may independently influence body composition and PA patterns, thereby confounding the intervention effects. Additionally, the study was conducted in a specific geographic region characterized by a mild Mediterranean climate and favorable weather conditions, which may facilitate higher outdoor activity levels. This fact naturally limits the generalizability of the findings to regions with different environmental contexts. Moreover, even though a correction for multiple comparisons was applied, the risk of Type I error was reduced but not fully eliminated, given the number of variables examined. Future studies with larger samples should consider adjustment procedures to minimize this statistical bias.

Despite these limitations, this study has several notable strengths that enhance its credibility. First, and probably most importantly, PA was assessed via a combination of objective and subjective methods (directly through accelerometers and indirectly via standardized questionnaires), allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of children’s PA patterns. Second, body composition was systematically measured via technologically advanced and validated equipment, providing accurate and reliable data on body composition parameters. Third, the inclusion of gender-specific analyses allowed for a more nuanced understanding of potential differences in response to the experimental schooling program, offering clear insights into how boys and girls may respond differently. We believe that these methodological strengths contribute to the robustness of the study and its relevance for informing the quality and effectiveness of the analyzed experimental schooling program.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that, compared with regular schooling, participation in an experimental whole-day school program positively influences PA among children, particularly boys. Given the differences between observed schooling programs, our results underscore the impact of both PE frequency and teacher qualifications on children’s activity levels. However, gender-specific patterns suggest that boys benefited more from the intervention, which may reflect differences in engagement during both structured and unstructured physical activities in the experimental program.

Despite positive changes in PA, we did not observe significant effects on body composition indices. This outcome could be explained by the relatively short study period (one school year) and the absence of accompanying dietary strategies. Additionally, it is probable that natural growth and maturation processes additionally altered the effects of increased PA on changes in body composition. Therefore, we suggest the use of integrated interventions that combine PA with dietary education to address body composition outcomes in this age group.

In addition to providing evidence of the specific effects of the studied national experimental schooling program applied in Croatia, this research highlights the potential value of whole-of-school approaches in promoting PA. While the results are promising, they also highlight the complexity of influencing health-related outcomes in children and the need for sustained, multifaceted interventions. Future research should explore long-term effects, incorporate nutritional components, and further investigate gender-responsive strategies in PA programming. Additionally, changes in fitness status in children involved in program of whole day schooling, should be investigated in future studies.