MVL-Loc: Leveraging Vision-Language Model for Generalizable Multi-Scene Camera Relocalization

Abstract

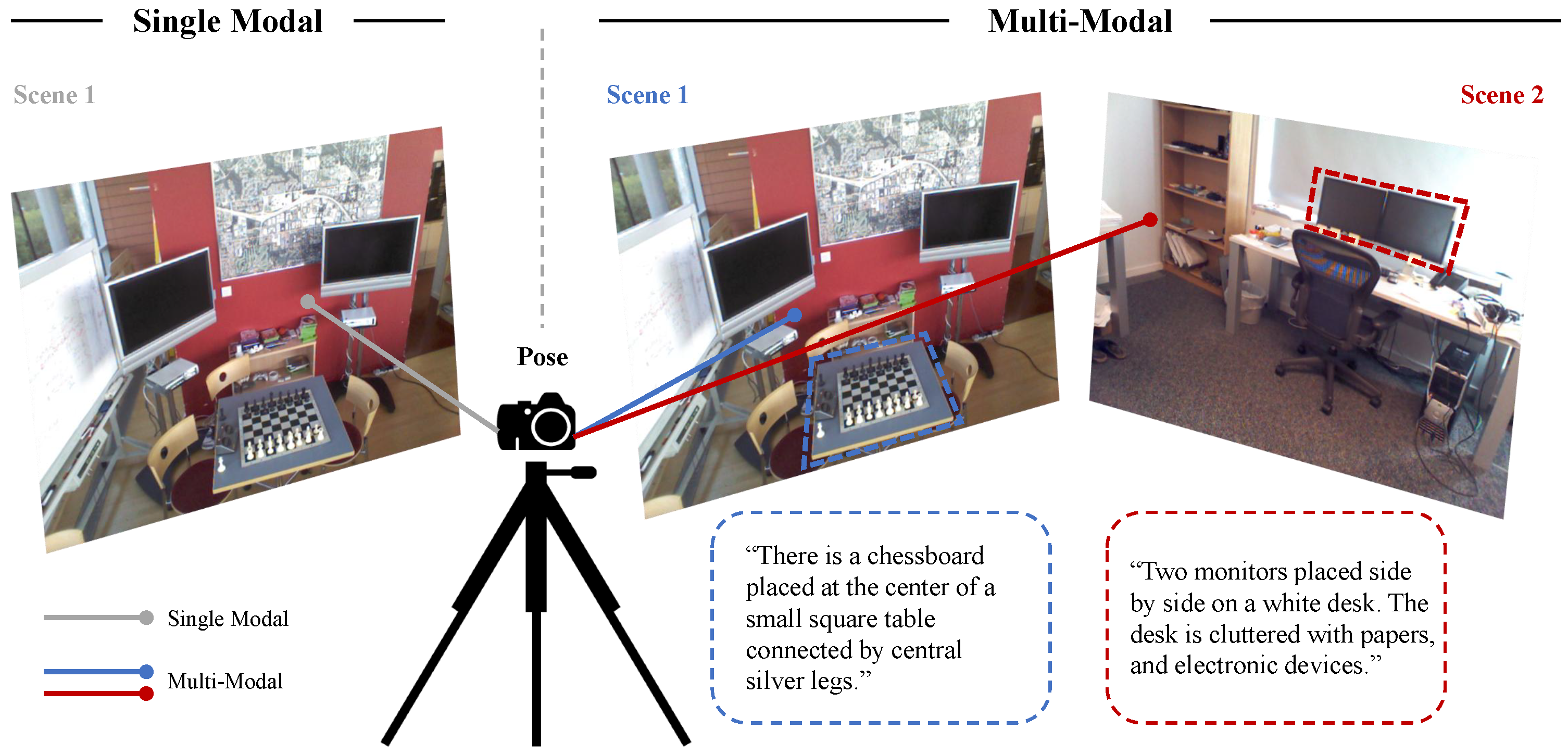

1. Introduction

- We propose MVL-Loc, a novel multi-scene camera relocalization framework that harnesses pretrained world knowledge from vision-language models (VLMs), effectively generalizing to both indoor and outdoor environments.

- We leverage natural language as a guiding tool for the multi-scene learning process of VLMs, enabling a deep semantic understanding of complex scenes and capturing the spatial relationships between objects and scenes.

- Through extensive experiments on common benchmarks, i.e., 7-Scenes and Cambridge Landmarks datasets, we demonstrate that our MVL-Loc framework achieves state-of-the-art performance in the task of end-to-end multi-scene camera relocalization.

2. Related Work

2.1. Deep Learning for Camera Relocalization

2.2. Vision-Language Models for Geospatial Reasoning

3. Multi-Scene Visual Language Localization

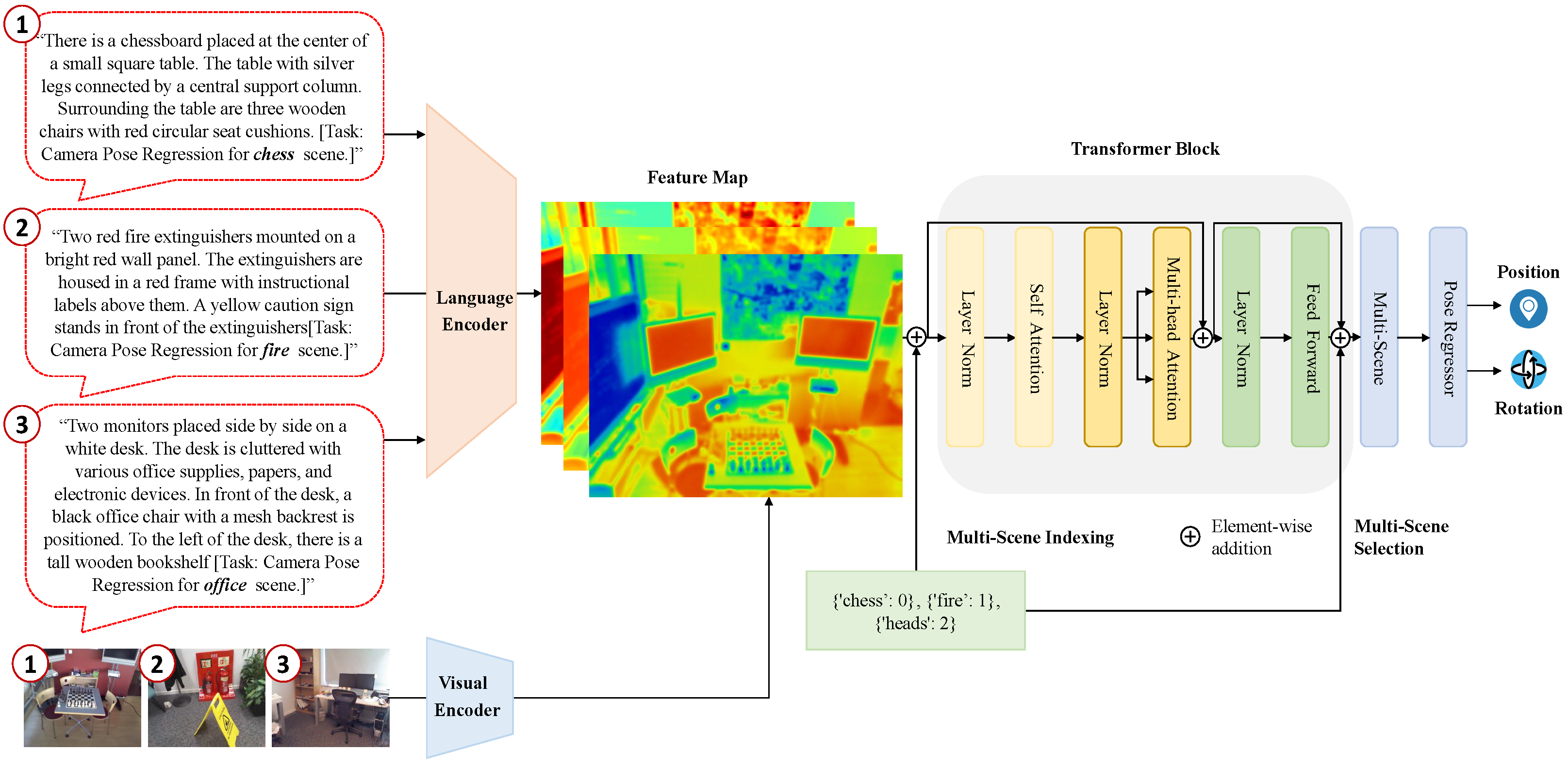

3.1. MVL-Loc Framework

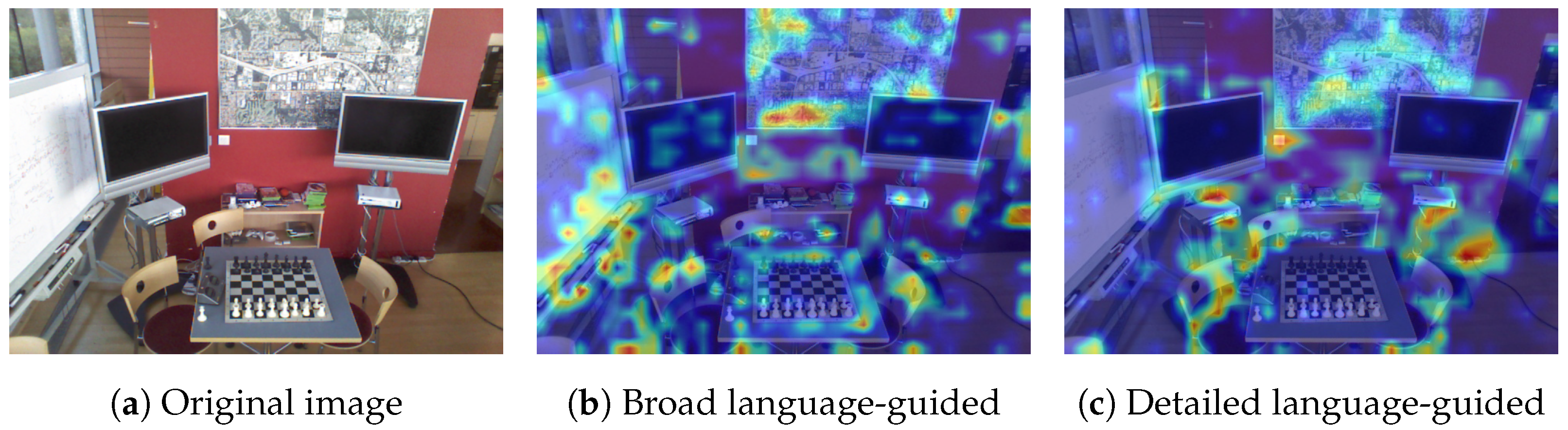

3.2. Language-Guided Camera Relocalization

3.3. Multi-Scene Camera Pose Regression

4. Experiments

4.1. Implementation Details

4.2. Datasets

4.3. Baselines

4.4. Quantitative Results Analysis

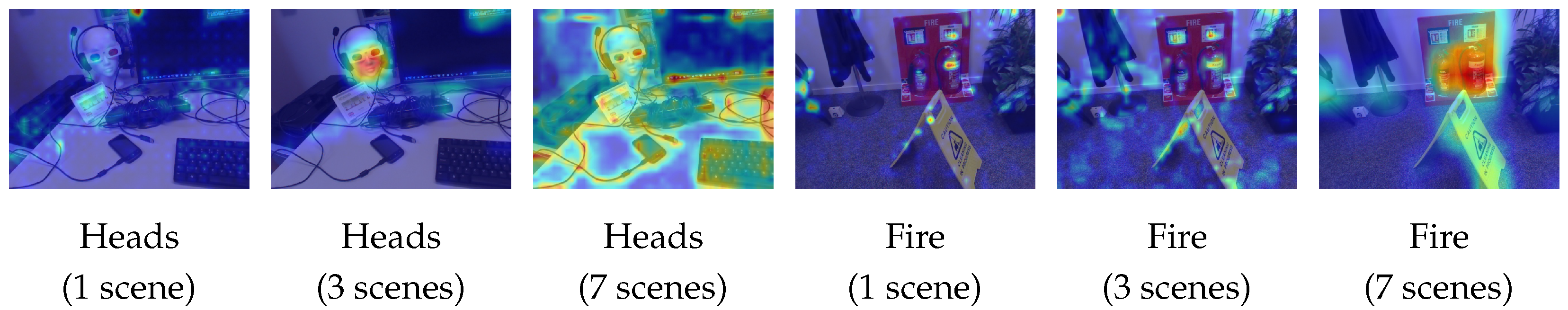

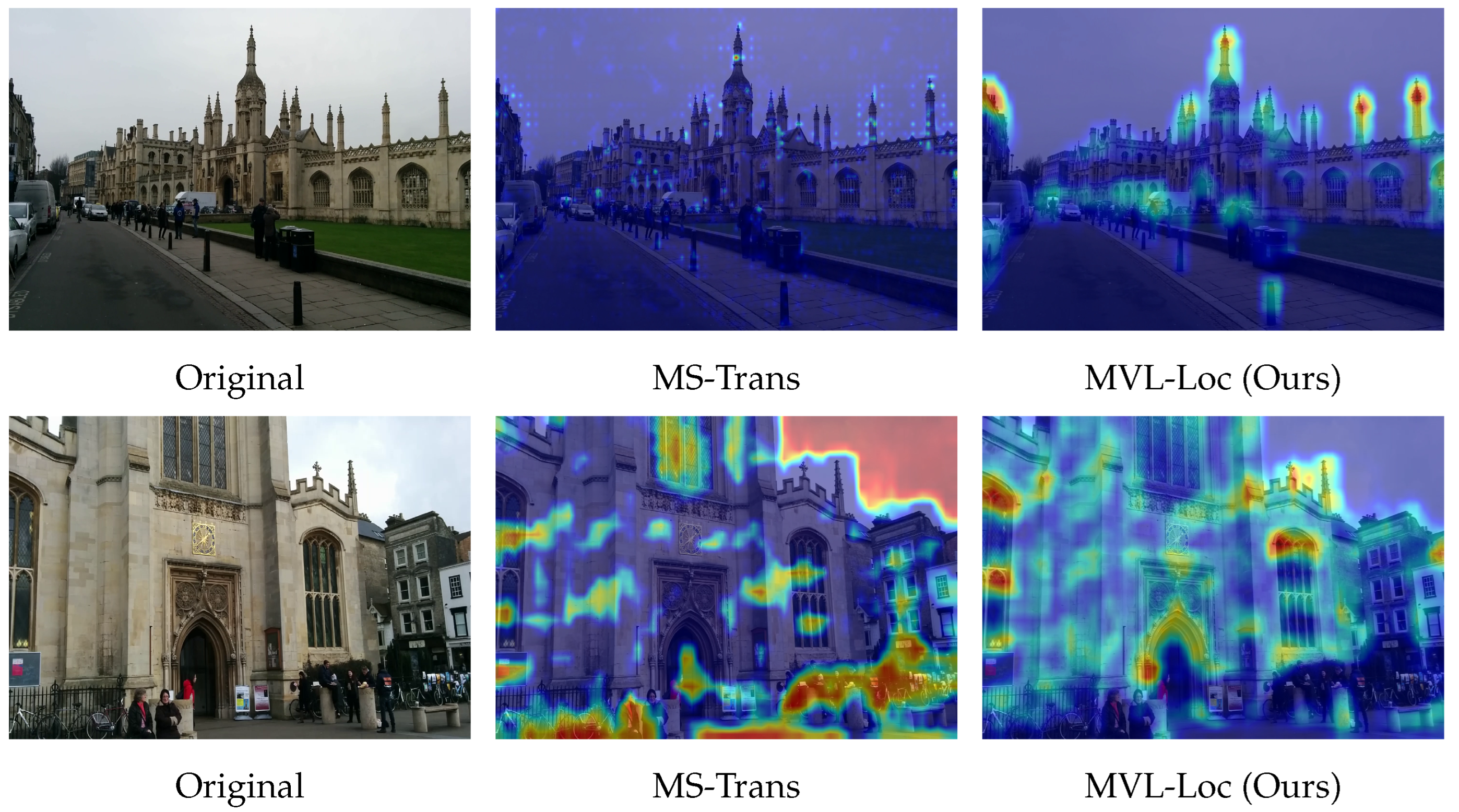

4.5. Visualization of Multi-Scene Fusion

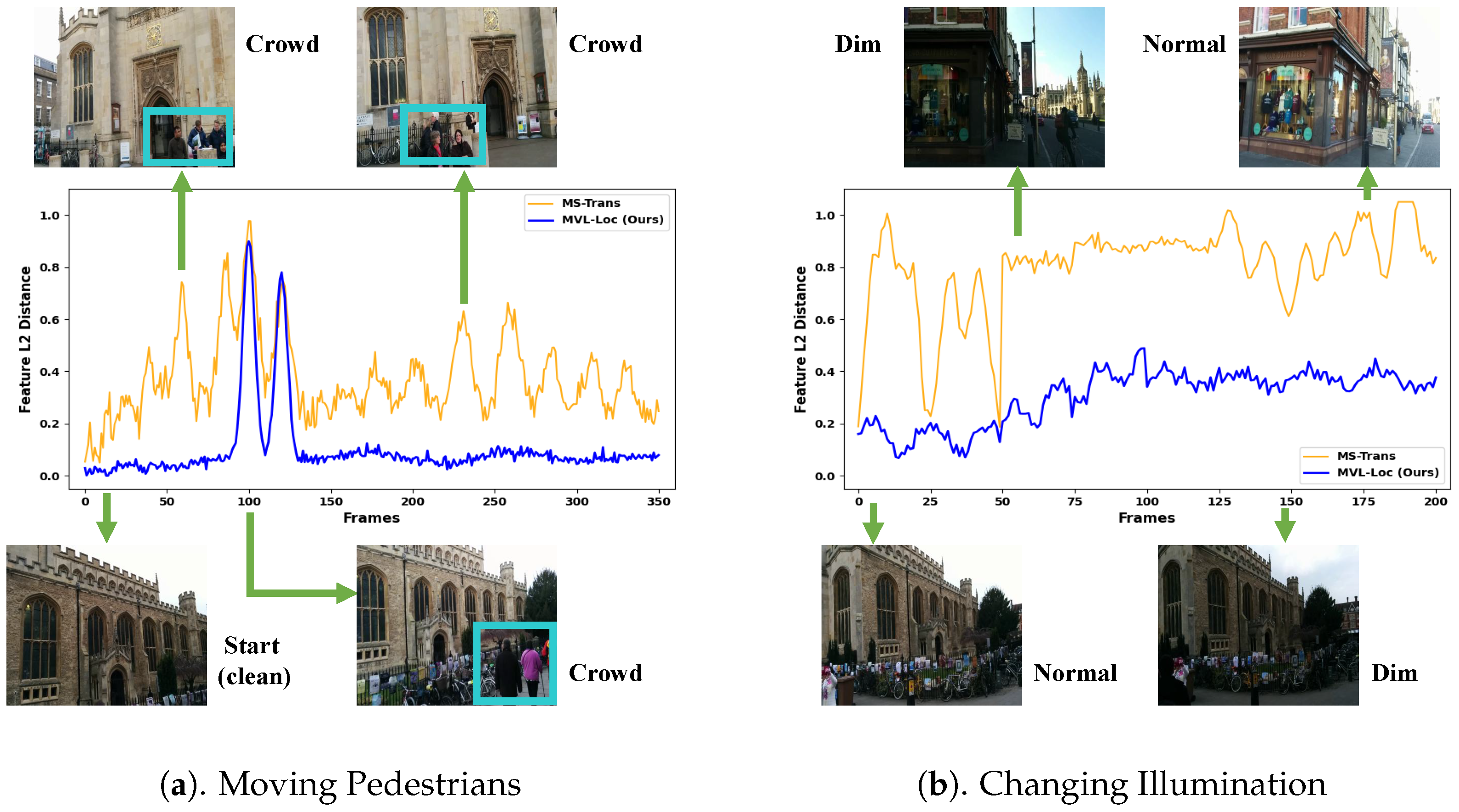

4.6. Feature Stability Under Dynamic Conditions

5. Ablation Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random Sample Consensus: A Paradigm for Model Fitting with Applications to Image Analysis and Automated Cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, A.; Grimes, M.; Cipolla, R. Posenet: A convolutional network for real-time 6-dof camera relocalization. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Geometric loss functions for camera pose regression with deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R.; Wang, S.; Markham, A.; Trigoni, N.; Wen, H. Vidloc: A deep spatio-temporal model for 6-dof video-clip relocalization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Chen, C.; Lu, C.X.; Zhao, P.; Trigoni, N.; Markham, A. Atloc: Attention guided camera localization. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 10393–10401. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Chen, C.; Yang, S.; Wei, W. EffLoc: Lightweight Vision Transformer for Efficient 6-DOF Camera Relocalization. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 8529–8536. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Hong, Y.; Wu, Q. NavGPT: Explicit Reasoning in Vision-and-Language Navigation with Large Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.16986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Carbajal, J.; Chebotar, Y.; Chen, X. RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.15818. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton, H.; Greenwell, C.; Workman, S.; Jacobs, N. Extending Absolute Pose Regression to Multiple Scenes. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Shavit, Y.; Ferens, R.; Keller, Y. Coarse-to-Fine Multi-Scene Pose Regression with Transformers. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 14222–14233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.M.; Baatz, G.; Köser, K.; Tsai, S.S.; Vedantham, R.; Pylvänäinen, T.; Roimela, K.; Chen, X.; Bach, J.; Pollefeys, M.; et al. City-scale landmark identification on mobile devices. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 20–25 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shavit, Y.; Ferens, R.; Keller, Y. Learning Multi-Scene Absolute Pose Regression with Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2713–2722. [Google Scholar]

- Brahmbhatt, S.; Gu, J.; Kim, K.; Hays, J.; Kautz, J. Geometry-aware learning of maps for camera localization. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Oh, J. FusionLoc: Camera-2D LiDAR Fusion Using Multi-Head Self-Attention for End-to-End Serving Robot Relocalization. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 75121–75133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July 2021; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Tan, H.; Bansal, M. Envedit: Environment Editing for Vision-and-Language Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 15386–15396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, R.; Krawez, M.; Burgard, W. FM-Loc: Using Foundation Models for Improved Vision-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; pp. 1381–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Sugino, T.; Tanaka, K.; Sha, Z.; Nakaoka, S.; Yoshizawa, S.; Shintani, K. CLIP-Loc: Multi-modal Landmark Association for Global Localization in Object-based Maps. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 13673–13679. [Google Scholar]

- Manvi, R.; Khanna, S.; Mai, G.; Burke, M.; Lobell, D.B.; Ermon, S. GeoLLM: Extracting Geospatial Knowledge from Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zeng, W. GeoReasoner: Geo-localization with Reasoning in Street Views using a Large Vision-Language Model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Albin, D.; Mauceri, C.; Woods, D.; Heckman, C. Spatial-LLaVA: Enhancing Large Language Models with Spatial Referring Expressions for Visual Understanding. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.12194. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Müller, T.; Park, Y. UniSceneVL: A Unified Vision-Language Model for 3D Scene Understanding and Spatial Correspondence Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 5521–5532. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.; Ye, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Han, X.; Yang, W. Advancing pose-guided image synthesis with progressive conditional diffusion models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06313. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, F.; Ye, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Han, X.; Wei, Y. Boosting consistency in story visualization with rich-contextual conditional diffusion models. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 6785–6794. [Google Scholar]

- Criminisi, A.; Shotton, J.; Glocker, B.; Izadi, S.; Fitzgibbon, A. 7-Scenes RGB-D Dataset. In Proceedings of the Microsoft Research Cambridge Vision and Graphics Group Dataset Release, Cambridge, UK, 1 January 2013; Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/project/rgb-d-dataset-7-scenes/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Modelling uncertainty in deep learning for camera relocalization. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, 16–21 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Walch, F.; Hazirbas, C.; Leal-Taixe, L.; Sattler, T.; Hilsenbeck, S.; Cremers, D. Image-based localization using lstms for structured feature correlation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shavit, Y.; Ferens, R. Do We Really Need Scene-specific Pose Encoders? In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 3186–3192. [Google Scholar]

- Melekhov, I.; Ylioinas, J.; Kannala, J.; Rahtu, E. Image-Based Localization Using Hourglass Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 870–877. [Google Scholar]

| King’s College | Old Hospital | Shop Façade | St Mary’s Church | Average | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Scene | PoseNet [2] | 1.94 m, 5.43° | 0.61 m, 2.92° | 1.16 m, 3.92° | 2.67 m, 8.52° | 1.60 m, 5.20° |

| BayesianPoseNet [26] | 1.76 m, 4.08° | 2.59 m, 5.18° | 1.27 m, 7.58° | 2.13 m, 8.42° | 1.94 m, 6.32° | |

| MapNet [13] | 1.08 m, 1.91° | 1.96 m, 3.95° | 1.51 m, 4.26° | 2.02 m, 4.57° | 1.64 m, 3.67° | |

| PoseNet17 [3] | 1.62 m, 2.31° | 2.64 m, 3.93° | 1.16 m, 5.77° | 2.95 m, 6.50° | 2.09 m, 4.63° | |

| IRPNet [28] | 1.21 m, 2.19° | 1.89 m, 3.42° | 0.74 m, 3.51° | 1.89 m, 4.98° | 1.43 m, 3.53° | |

| PoseNet-Lstm [27] | 0.99 m, 3.74° | 1.53 m, 4.33° | 1.20 m, 7.48° | 1.54 m, 6.72° | 1.32 m, 5.57° | |

| Multi-Scene | MSPN [9] | 1.77 m, 3.76° | 2.55 m, 4.05° | 2.92 m, 7.49° | 2.67 m, 6.18° | 2.48 m, 5.37° |

| MS-Trans [12] | 0.85 m, 1.63° | 1.83 m, 2.43° | 0.88 m, 3.11° | 1.64 m, 4.03° | 1.30 m, 2.80° | |

| c2f-MsTrans [10] | 0.71 m, 2.71° | 1.50 m, 2.98° | 0.61 m, 2.92° | 1.16 m, 3.92° | 0.99 m, 3.13° | |

| MVL-Loc (ours) | 0.62 m, 1.69° | 1.38 m, 2.41° | 0.59 m, 3.21° | 1.09 m, 3.82° | 0.92 m, 2.79° |

| Chess | Fire | Heads | Office | Pumpkin | Kitchen | Stairs | Average | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Scene | PoseNet [2] | 0.32 m, 7.60° | 0.48 m, 14.6° | 0.31 m, 12.2° | 0.48 m, 7.68° | 0.47 m, 8.42° | 0.59 m, 8.64° | 0.47 m, 13.81° | 0.45 m, 10.42° |

| Bayesian [26] | 0.38 m, 7.24° | 0.43 m, 13.8° | 0.30 m, 12.3° | 0.49 m, 8.09° | 0.63 m, 7.18° | 0.59 m, 7.59° | 0.48 m, 13.22° | 0.47 m, 9.91° | |

| PN-Lstm [27] | 0.24 m, 5.79° | 0.34 m, 12.0° | 0.22 m, 13.8° | 0.31 m, 8.11° | 0.34 m, 7.03° | 0.37 m, 8.83° | 0.41 m, 13.21° | 0.32 m, 9.82° | |

| PoseNet17 [3] | 0.14 m, 4.53° | 0.29 m, 11.5° | 0.19 m, 13.1° | 0.20 m, 5.62° | 0.27 m, 4.77° | 0.24 m, 5.37° | 0.36 m, 12.53° | 0.24 m, 8.20° | |

| IRPNet [28] | 0.13 m, 5.78° | 0.27 m, 9.83° | 0.17 m, 13.2° | 0.25 m, 6.41° | 0.23 m, 5.83° | 0.31 m, 7.32° | 0.35 m, 11.91° | 0.24 m, 8.61° | |

| Hourglass [29] | 0.15 m, 6.18° | 0.27 m, 10.83° | 0.20 m, 11.6° | 0.26 m, 8.59° | 0.26 m, 7.32° | 0.29 m, 10.7° | 0.30 m, 12.75° | 0.25 m, 9.71° | |

| AtLoc [5] | 0.11 m, 4.37° | 0.27 m, 11.7° | 0.16 m, 11.9° | 0.19 m, 5.61° | 0.22 m, 4.54 | 0.25 m, 5.62° | 0.28 m, 10.9° | 0.21 m, 7.81° | |

| MultiScene | MSPN [9] | 0.10 m, 4.76° | 0.29 m, 11.5° | 0.17 m, 13.2° | 0.17 m, 6.87° | 0.21 m, 5.53° | 0.23 m, 6.81° | 0.31 m, 11.81° | 0.21 m, 8.64° |

| MS-Trans [12] | 0.11 m, 4.67° | 0.26 m, 9.78° | 0.16 m, 12.8° | 0.17 m, 5.66° | 0.18 m, 4.44° | 0.21 m, 5.99° | 0.29 m, 8.45° | 0.20 m, 7.40° | |

| c2f-MsTrans [10] | 0.10 m, 4.63° | 0.25 m, 9.89° | 0.14 m, 12.5° | 0.16 m, 5.65° | 0.16 m, 4.42° | 0.18 m, 6.29° | 0.27 m, 7.86° | 0.18 m, 7.32° | |

| MVL-Loc | 0.09 m, 3.95° | 0.22 m, 9.45° | 0.11 m, 11.6° | 0.14 m, 5.60° | 0.16 m, 3.82° | 0.14 m, 6.11° | 0.23 m, 8.11° | 0.16 m, 6.95° |

| Pre-Trained | WK | LD | MT | 7 Scenes | Cambridge Landmarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImageNet | × | × | × | 0.28 m, 7.97° | 1.63 m, 4.76° |

| CLIP | ✓ | × | × | 0.22 m, 7.38° | 1.33 m, 3.57° |

| CLIP | ✓ | ✓ | × | 0.18 m, 7.10° | 1.01 m, 3.05° |

| CLIP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.16 m, 6.98° | 0.93 m, 2.90° |

| Method | Dataset | Avg. Position Error (m) | Avg. Rotation Error (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MVL-Loc (Ours) | 7Scenes | 0.16 | 6.98 |

| FM-Loc | 7Scenes | 0.19 | 7.60 |

| Glo-Loc | 7Scenes | 0.22 | 8.50 |

| MVL-Loc (Ours) | Cambridge | 0.93 | 2.90 |

| FM-Loc | Cambridge | 1.05 | 3.20 |

| Glo-Loc | Cambridge | 1.10 | 3.50 |

| Vision-Language Encoder | 7Scenes | Cambridge Land. |

|---|---|---|

| BLIP-2 | 0.18 m, 7.13° | 0.98 m, 3.16° |

| OpenFlamingo | 0.19 m, 7.21° | 1.03 m, 3.19° |

| Clip | 0.16 m, 6.98° | 0.93 m, 2.90° |

| Decoder Layers | 7Scenes | Cambridge Landmarks |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.54 m, 8.15° | 1.71 m, 3.93° |

| 4 | 0.16 m, 6.98° | 0.93 m, 2.90 |

| 6 | 0.17 m, 7.02° | 0.97 m, 2.99° |

| 8 | 0.17 m, 7.16° | 0.98 m, 3.01° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, Z.; Yang, S.; Ji, S.; Yin, J.; Wen, Z.; Wei, W. MVL-Loc: Leveraging Vision-Language Model for Generalizable Multi-Scene Camera Relocalization. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12642. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312642

Xiao Z, Yang S, Ji S, Yin J, Wen Z, Wei W. MVL-Loc: Leveraging Vision-Language Model for Generalizable Multi-Scene Camera Relocalization. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12642. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312642

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Zhendong, Shan Yang, Shujie Ji, Jun Yin, Ziling Wen, and Wu Wei. 2025. "MVL-Loc: Leveraging Vision-Language Model for Generalizable Multi-Scene Camera Relocalization" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12642. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312642

APA StyleXiao, Z., Yang, S., Ji, S., Yin, J., Wen, Z., & Wei, W. (2025). MVL-Loc: Leveraging Vision-Language Model for Generalizable Multi-Scene Camera Relocalization. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12642. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312642