Recreation of Gap Test with Damaged Plasticity Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The Drucker-Prager model returns no weakening phase in the diagram of evolution of the fracture energy Gf vs. T-stress;

- The CDPM2 model, described by Grassl et al. [6], shows some significant discrepancies in the Gf–T-stress diagram compared with experimental results;

- The Mohr–Coulomb model produces an artificial stiffening effect at the crack tip;

- The cohesive crack model (CCM) is a line crack model; so it cannot capture any effect of the T-stress.

2. Research Significance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP) Model

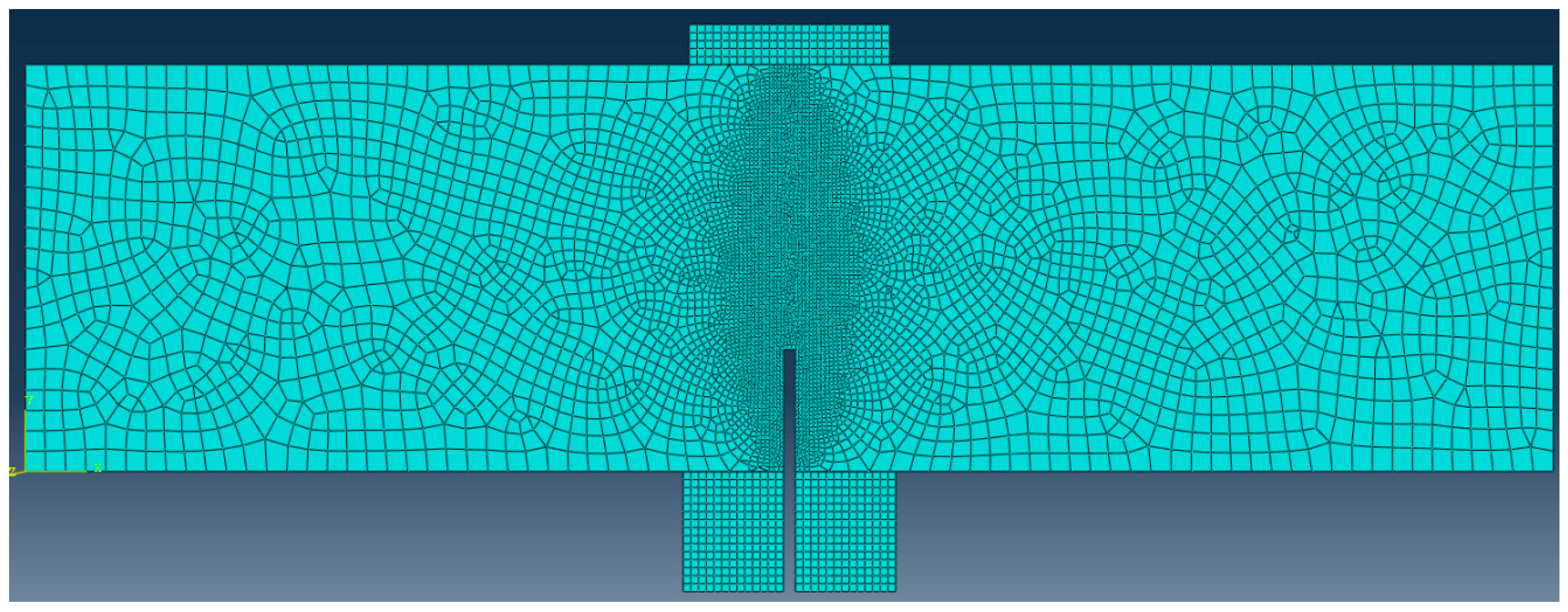

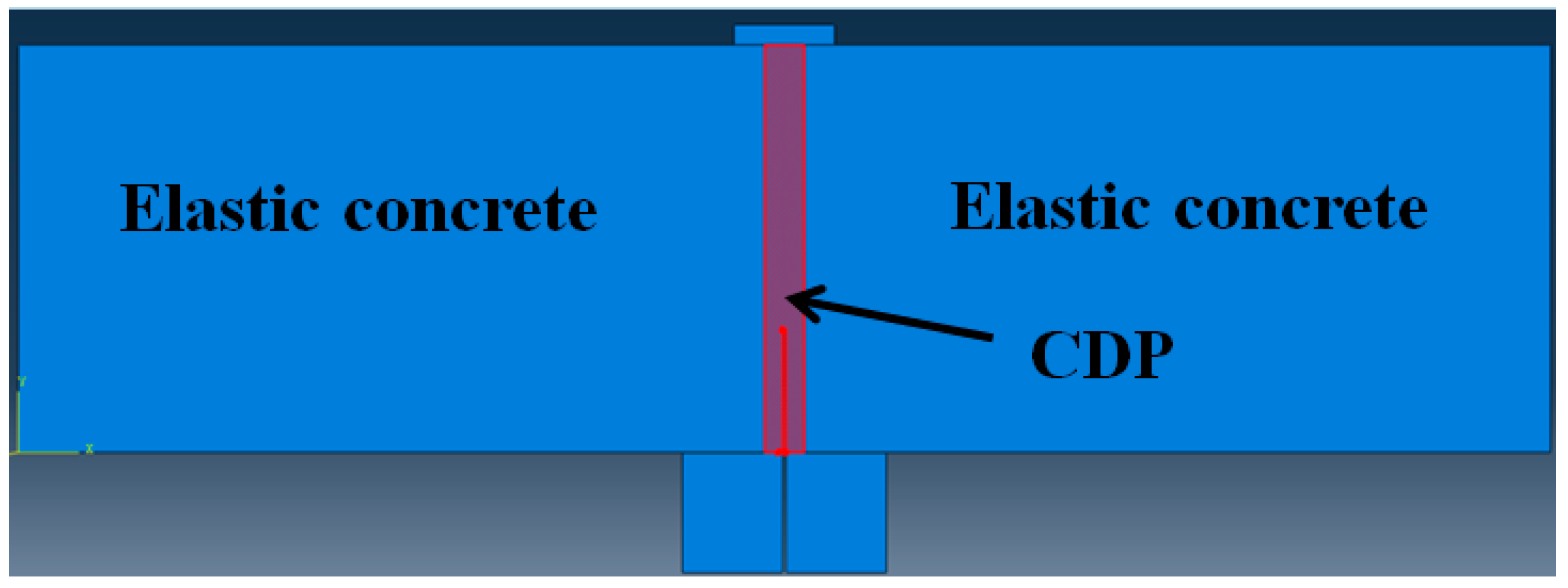

3.3. Setup of the Numerical Model

4. Results

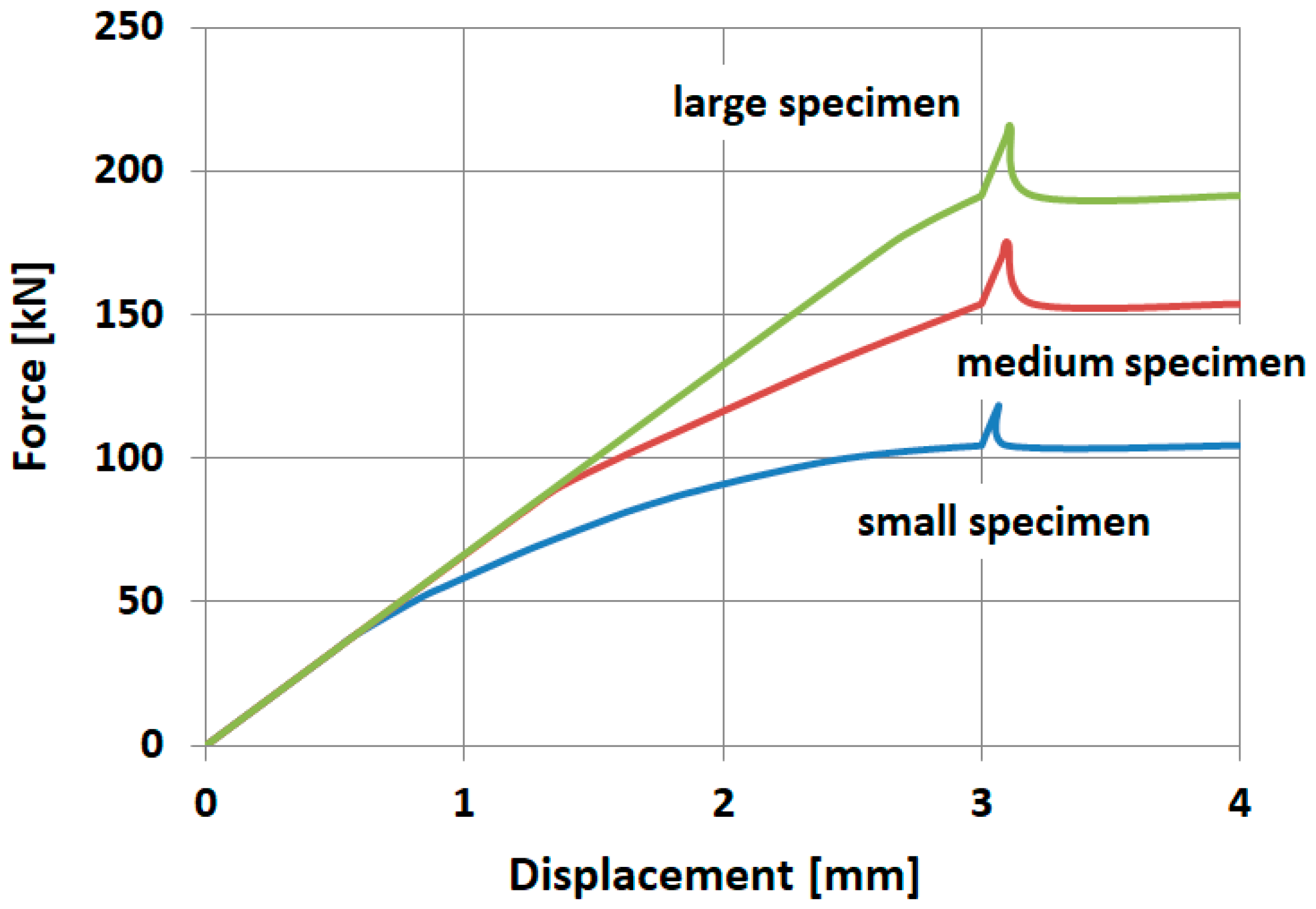

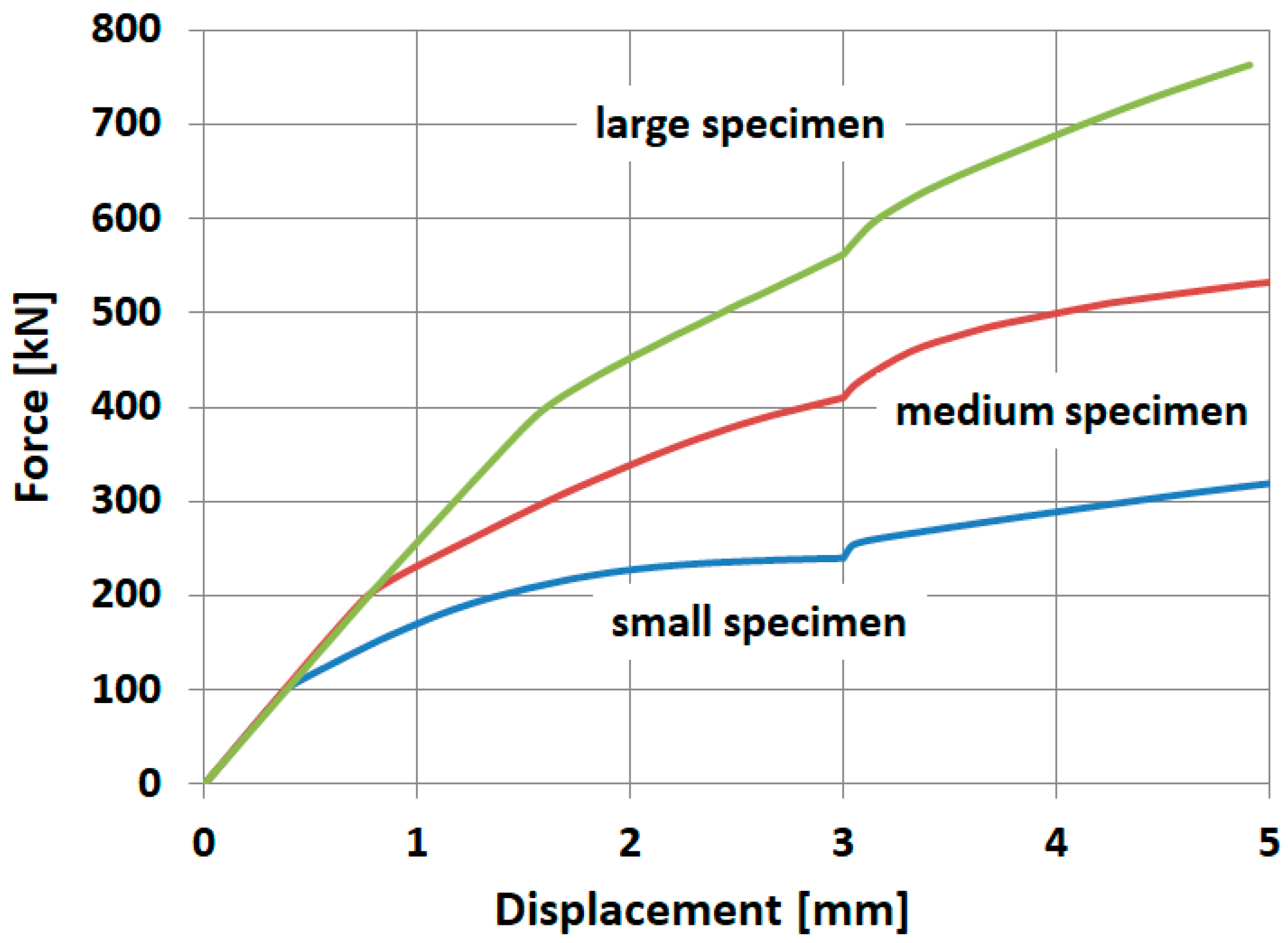

- A force vs. displacement diagram and an extracted peak force; the force means vertical reaction in the steel pad, where the displacement was imposed;

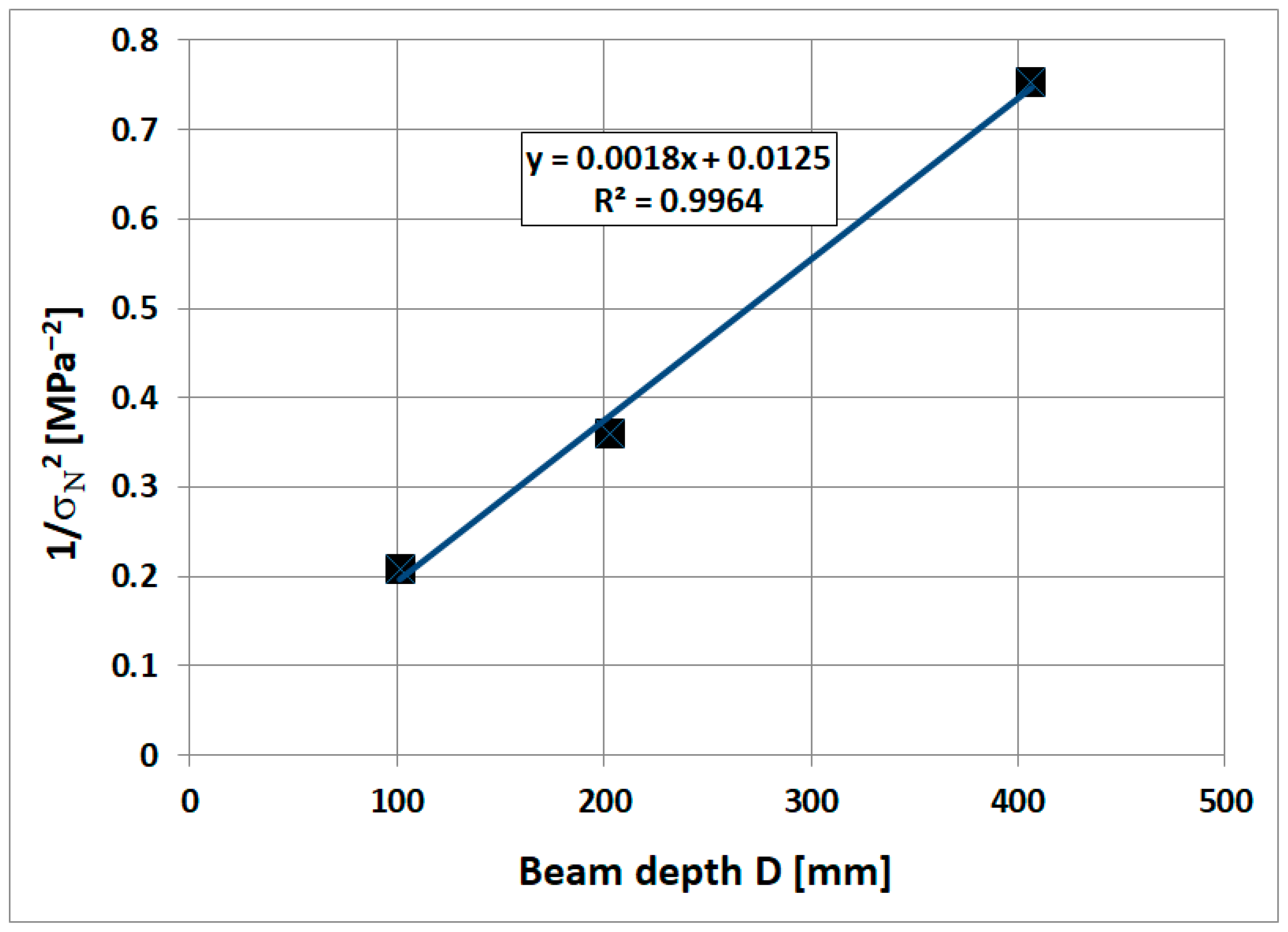

- A nominal stress σN vs. beam depth diagram with a linear regression line and calculations of the initial fracture energy Gf.

- Gf = 255.5 Nm−1 in the case of the T-stress equal to 0.4fc;

- Gf = 76.6 Nm−1 in the case of the T-stress equal to 0.9fc;

- Gf = 139.3 Nm−1 in the case of the T-stress equal to 0.

- cf = 2.01 cm if the normal stress is equal to 0;

- cf = 1.01 cm if the normal stress is equal to 0.4fc;

- cf = 1.67 cm if the normal stress is equal to 0.9fc.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The CDP model can recreate the gap test correctly, but only when the damage conditions in tension are specified;

- The initial fracture energy changes with the changing normal stress (the T-stress) in the same way as in the research of Nguyen et al. [1], and the gap test revealed this fact;

- A clear plateau before the initiation of the cracking process in the force–displacement diagram has not previously been obtained in the case of the medium and the large specimen, but this fact did not disturb the extraction of the peak force.

- The authors of this paper intend to continue their work on the gap test, especially in terms of the following:

- Using different material models and different software;

- Calculating the total fracture energy from the force vs. CMOD (crack mouth opening displacement) diagram;

- Performing the gap test for other materials, for instance ceramics or fiber-reinforced concrete.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDP | Concrete damaged plasticity |

| LEFM | Linear elastic fracture mechanics |

| CCM | Cohesive crack model |

| PF | Phase field |

| PD | Peridynamics |

| CBM | Crack band model |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| CDPM2 | Concrete damaged plasticity “model 2” |

| CMOD | Crack mouth opening distance |

| FPZ | Fracture processing zone |

References

- Nguyen, H.T.; Pathirage, M.; Rezaei, M.; Issa, M.; Cusatis, G.; Bažant, Z.P. New perspective of fracture mechanics inspired by gap test with crack-parallel compression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14015–14020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Qiang, Y.; Cusatis, G.; Cedolin, L.; Jirásek, M. Misconceptions on Variability of Fracture Energy, Its Uniaxial Definition by Work of Fracture, and Its Presumed Dependence on Crack Length and Specimen Size. In Fracture Mechanics of Concrete and Concrete Structures—Recent Advances in Fracture Mechanics of Concrete; Oh, B.H., Choi, O.C., Chung, L., Eds.; Korea Concrete Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010; pp. 29–37. Available online: https://framcos.org/FraMCoS-7/01-05.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Nguyen, H.T.; Pathirage, M.; Cusatis, G.; Bažant, Z.P. Gap Test of Crack-Parallel Stress Effect on Quasibrittle Fracture and Its Consequences. J. App. Mech. 2020, 87, 071012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Dönmez, A.A. Reappraisal of phase-field, peridynamics and other fracture models in light of classical fracture tests and new gap test. In Computational Modelling of Concrete and Concrete Structures, 1st ed.; Meschke, G., Pichler, B., Rots, J., Eds.; CRC Press/Balkema: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Nguyen, H.T.; Dönmez, A.A. Critical Comparison of Phase-Field, Peridynamics, and Crack Band Model M7 in Light of Gap Test and Classical Fracture Tests. J. App. Mech. 2022, 89, 061008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassl, P.; Xenos, D.; Nyström, U.; Rempling, R.; Gylltoft, K. A damage-plasticity approach to modelling the failure of concrete. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2013, 50, 3805–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Dönmez, A.A.; Nguyen, H.T. Précis of gap test results requiring reappraisal of line crack and phase-field models of fracture mechanics. Eng. Struct. 2022, 250, 113285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Pathirage, M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Bažant, Z.P.; Cusatis, G. Dissipation mechanisms of crack-parallel stress effects on fracture process zone in concrete. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2023, 181, 105439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, J.; Salviato, M. The Gap Test–Effects of Crack Parallel Compression on Fracture in Carbon Fiber Composites. Compos. Part A 2023, 164, 107252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, H.; Nguyen, H.T.; Bažant, Z.P.; Hubler, M.H. Crack-Parallel Stress Effect on Fracture of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Revealed by Gap Tests. J. Eng. Mech. 2024, 150, 04024011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P. Scaling of Structural Strength, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Gopalaratnam, V.S.; Buyukozturk, O.; Cedolin, L.; Elices, M.; Darwin, D.; Li, V.C.; Lin, F.B.; Mau, S.T.; Naaman, A.E.; et al. Fracture Mechanics of Concrete: Concepts, Models and Determination of Material Properties; Reported by ACI Committee 446, Fracture Mechanics; ACI Committee: Evanston, IL, USA, 1989; Available online: https://framcos.org/FraMCoS-1/State-of-Art-1992.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Bažant, Z.P. Scaling theories for quasibrittle fracture: Recent advances and new directions. In Fracture Mechanics of Concrete Structures, Proceedings FRAMCOS-2; Wittman, F.H., Ed.; AEDIFICATIO Publishers: Freiburg, Germany, 1995; pp. 515–534. Available online: https://framcos.org/FraMCoS-2/1-6-1.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- van Vliet, M.R.A.; van Mier, J.G.M. Experimental investigation of size effect in concrete under uniaxial tension. In Fracture Mechanics of Concrete Structures, Proceedings FRAMCOS-3; AEDIFICATIO Publishers: Freiburg, Germany, 1995; pp. 1923–1936. Available online: https://framcos.org/FraMCoS-3/3-15-2.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Cedolin, L.; Cusatis, G. Cohesive fracture and size effect in concrete. In New Trends in Fracture Mechanics of Concrete, Volume 1 of the Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Fracture Mechanics of Concrete and Concrete Structures FraMCoS-6, Catania, Italy, 17 June 2017; Carpintieri, A., Gambarova, P., Ferro, G., Plizzari, G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; Available online: https://framcos.org/FraMCoS-6/284.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Saouma, V.E.; Barton, C.C. Fractals, fractures, and size effects in concrete. J. Eng. Mech. 1994, 120, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saouma, V.E.; Fava, G. On fractals and size effect. Int. J. Frac 2006, 137, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Kazemi, M.T. Size Effect in Fracture of Ceramics and Its Use To Determine Fracture Energy and Effective Process Zone Length. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1990, 73, 1841–1853. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00047063 (accessed on 25 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Abaqus/CAE. User’s Guide, Version 2017; Dassault Systemes Simulia Corp: Johnston, RI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lubliner, J.; Oliver, J.; Oller, S.; Oñate, E. A plastic-damage model for concrete. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1989, 25, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Fenves, G.L. Plastic-damage model for cyclic loading of concrete structures. ASCE J. Eng. Mech. 1998, 124, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvaut, G.; Lions, I.J. Les Inequations en Mechanique et en Physique; Dunod: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicki, A.; Wosatko, A.; Szczecina, M. Deterministic size effect in concrete simulated with two viscoplatic models. In 6th. European Conference on Computational Mechanics (Solids, Structures and Coupled Problems) ECCM 6, 7th. European Conference on Computational Fluid Dynamics ECFD 7, Glasgow, UK, 11–15 June 2018, 1st ed.; Owen, R., de Borst, R., Reese, J., Pearce, C., Eds.; International Centre for Numerical Methods in Engineering: Barcelona, Spain, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Shao, X.; Han, J.; Liu, Y. Development and Numerical Implementation of Plastic Damage Constitutive Model for Concrete Under Freeze–Thaw Cycling. Buildings 2025, 15, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, K.A.; Mahamid, M.; Hariri-Ardebili, M.A.; Tort, C.; Ford, T. Parameter Selection for Concrete Constitutive Models in Finite Element Analysis of Composite Columns. Buildings 2023, 13, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainone, L.S.; Tateo, V.; Casolo, S.; Uva, G. About the Use of Concrete Damage Plasticity for Modeling Masonry Post-Elastic Behavior. Buildings 2023, 13, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1992-1-1; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- International Federation for Structural Concrete (FIB) (Ed.) Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures 2010; Ernst & Sohn: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rots, J. Computational Modeling of Concrete Fracture. Ph.D. Dissertation, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 1988. Available online: https://repository.tudelft.nl/file/File_9a079a94-7b9f-4ecc-8124-ba12ed4a4345?preview=1 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Szczecina, M.; Winnicki, A. Calibration of the CDP model parameters in Abaqus. In Proceedings of the 2015 World Congress on Advances in Structural Engineering and Mechanics (ASEM15), Incheon, Republic of Korea, 25–29 August 2015; Available online: http://www.i-asem.org/publication_conf/asem15/3.CTCS15/1w/W1D.1.AWinnicki.CAC.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Wosatko, A.; Szczecina, M.; Winnicki, A. Selected Concrete Models Studied Using Willam’s Test. Materials 2020, 13, 4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczecina, M.; Winnicki, A. Rational Choice of Reinforcement of Reinforced Concrete Frame Corners Subjected to Opening Bending Moment. Materials 2021, 14, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willam, K.; Pramono, E.; Sture, S. Fundamental issues of smeared crack models. In Proceedings of the SEM-RILEM International Conference on Fracture of Concrete and Rock, Houston, TX, USA, 17–19 June 1987; pp. 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Elastic modulus | 35 GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.167 |

| Compressive strength of concrete | 40.5 MPa |

| Dilatancy angle | 15 degrees |

| Tensile strength | 3.5 MPa |

| Fracture energy | 142 Nm−1 |

| Relaxation time | 10−4 s |

| fb0/fc0 | 1.16 |

| Yield Stress [MPa] | Inelastic Strain |

|---|---|

| 16.2 | 0 |

| 40.5 | 0.001837 |

| 32.4 | 0.003037 |

| Damage Parameter | Cracking Strain |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 0.99 | 0.0733 |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Elastic modulus of steel | 210 GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio of steel | 0.30 |

| Elastic modulus of poly-propylene | 1.8 GPa |

| Poisson’s ratio of poly-propylene | 0.38 |

| Yield Stress [MPa] | Inelastic Strain |

|---|---|

| 20.0 | 0 |

| 30.0 | 0.0085 |

| 36.3 | 0.0159 |

| 40.0 | 0.0233 |

| 45.0 | 0.0392 |

| 47.0 | 0.0631 |

| 48.0 | 0.1392 |

| D [mm] | Peak Load [kN] | Nominal Stress σN [MPa] | 1/σN2 [MPa−2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 101.6 | 22.6 | 2.19 | 0.21 |

| 203.2 | 34.4 | 1.67 | 0.36 |

| 406.4 | 47.6 | 1.15 | 0.75 |

| D [mm] | Peak Load [kN] | Nominal Stress σN [MPa] | 1/σN2 [MPa−2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 101.6 | 12.0 | 1.16 | 0.74 |

| 203.2 | 19.0 | 0.92 | 1.18 |

| 406.4 | 26.0 | 0.63 | 2.52 |

| D [mm] | Peak Load [kN] | Nominal Stress σN [MPa] | 1/σN2 [MPa−2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 101.6 | 17.7 | 1.71 | 0.34 |

| 203.2 | 23.5 | 1.14 | 0.77 |

| 406.4 | 35.4 | 0.86 | 1.36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szczecina, M.; Winnicki, A. Recreation of Gap Test with Damaged Plasticity Model. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312606

Szczecina M, Winnicki A. Recreation of Gap Test with Damaged Plasticity Model. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312606

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzczecina, Michał, and Andrzej Winnicki. 2025. "Recreation of Gap Test with Damaged Plasticity Model" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312606

APA StyleSzczecina, M., & Winnicki, A. (2025). Recreation of Gap Test with Damaged Plasticity Model. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12606. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312606