5.1. Dataset

The dataset used in this study is based on the SliceSecure Dataset proposed by Khan et al. [

47]. This is an experimental traffic dataset directly constructed to reproduce DoS and DDoS attacks in a 5G network slicing environment. Unlike existing general-purpose network attack datasets such as CI-CIDS2017, CSE-CICIDS2018, and CIC-DDoS2019, it reflects the actual traffic characteristics collected from a 5G network slicing structure.

The SliceSecure Dataset was collected from a 5G slice testbed built using Free5GC (v3.0.5) and UERANSIM (v3.1.0). The test environment consisted of a total of 12 Virtual Machines (VMs), each using the Ubuntu 20.04 LTS operating system, 2 GB of RAM, and 2 vCPUs. The 5G core network includes key network functions such as AMF, SMF, NRF, and UPF. Slices 1 and 2 were configured through two user planes, UPF1 and UPF2, respectively. Each UE1–UE6 ran in separate VMs, with UE1–UE5 connected to Slice1 (UPF1) and UE6 connected to Slice2 (UPF2). In the attack scenario, UE2–UE5 sent attack traffic, while UE1 maintained normal traffic, and performance degradation was measured.

The attack traffic generated various DoS/DDoS modification attacks using the hping3 tool. The collected packets were captured using Wireshark and saved in pcap format. A total of 84 traffic features were extracted using the CICFlowMeter tool, and the converted data in CSV format was organized into a dataset. The dataset consists of approximately 5,000,000 traffic flow records, with each sample including benign and various attack types (tcp_syn, tcp_push, tcp_fin, tcp_xmas, tcp_ack, etc.).

In this study, approximately 191,000 balanced samples were extracted using a hierarchical balanced sampling method that considers both slices and labels simultaneously to ensure the representativeness of the dataset and efficient learning.

Table 4 presents the domain-based grouping of the 84 traffic features and shows which specific features are included in each group.

5.3. Experimental Setting

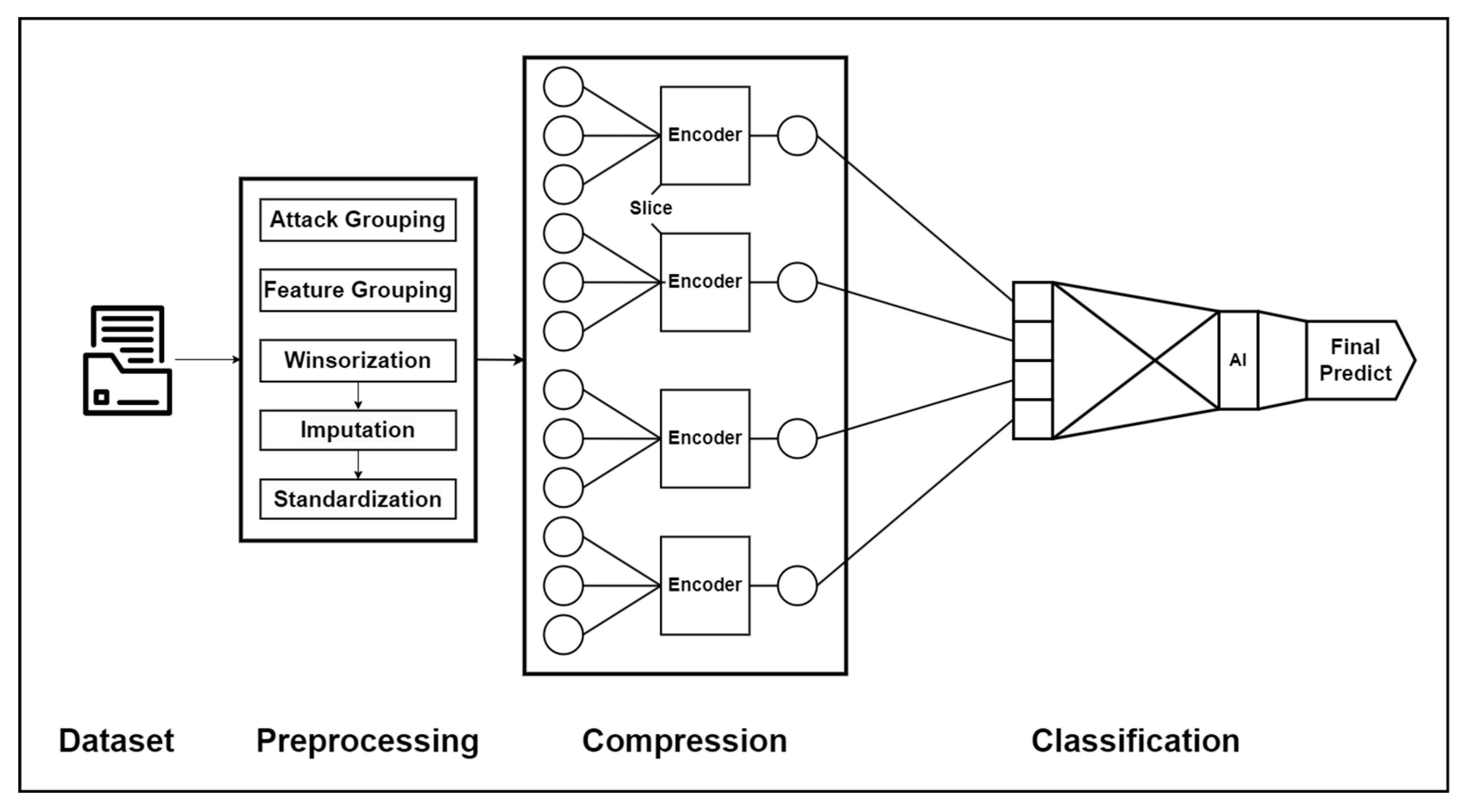

This section describes the experiments conducted to train and evaluate the proposed Autoencoder-SVM-based multi-class malicious traffic detection model. The same preprocessing pipeline (Winsorization, Imputation, Group-wise Standardization) and data split (Train 70%, Validation 15%, Test 15%) were applied, and reproducibility was ensured by fixing the random seed and class weights (class_weight = ‘balanced’). The model’s computational resource usage was measured in real-time using Resource Sampler and a timer, and each experiment was designed to be evaluated not only for accuracy but also for efficiency and reliability in a balanced manner.

For the classification stage, all experiments employed an SVM classifier and the complete parameter configuration is summarized in

Table 5. The same SVM settings were applied consistently across Experiment Set 1–4 to ensure a fair comparison. As shown in

Table 5, the SVM was configured using an RBF kernel (C = 1.0, gamma = scale), balanced class weight, probability estimation enabled and isotonic calibration with 3-fold cross-validation, with the random state varied from 41 to 45 in accordance with the overall experimental protocol.

The entire experiment consists of a total of four sets (Set 1–4), each designed to analyze the performance and efficiency of the proposed model from different objectives and perspectives.

The first set of experiments (Set 1) for comparing SVM performance by autoencoder structure is conducted to analyze the impact of changes in autoencoder structure on the detection performance of the SVM classifier. This experimental setting compares the following four model configurations.

- (1)

B1 (Raw + SVM): A base model trained by directly inputting the preprocessed original features.

- (2)

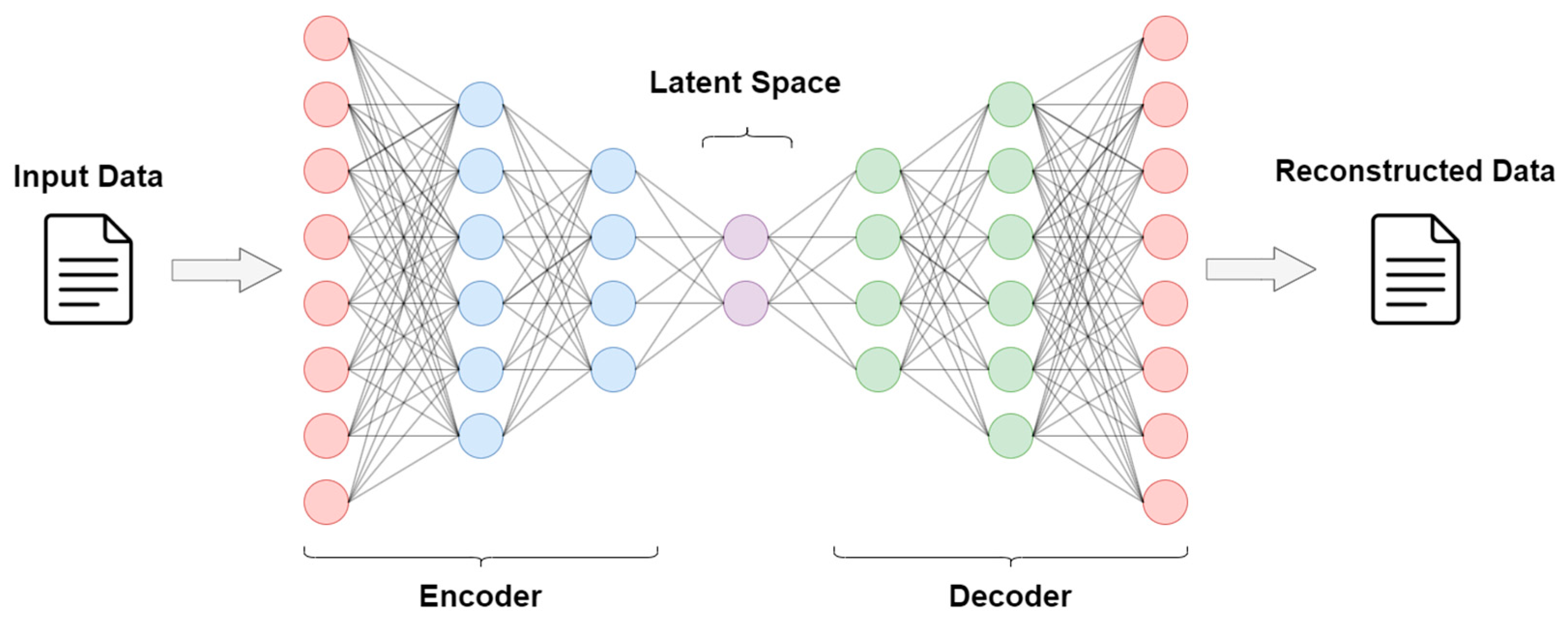

B2 (Single-AE + SVM): The latent representation obtained by compressing all features with a single autoencoder is used as input for the SVM. The encoder structure of the Single-AE model compresses 55 input features into a 13-dimensional latent representation for SVM classification, as shown in

Table 6.

- (3)

B3 (Multi-AE + SVM): Independent autoencoders for each feature group (Volume, Size, Timing, Session, Subflow, and Active) separated by domain are trained, and then the latent representations from each group are merged to be used as input for the SVM. The encoder structure of the Multi-AE model independently encodes nine feature groups and concatenates them into a 28-dimensional latent vector, as shown in

Table 7.

- (4)

B4 (MultiSingle-AE + SVM): A structure that removes redundant representations and maximizes efficiency by further compressing the latent representation generated by the Multi-AE into a single autoencoder for secondary compression. The two-stage encoder structure of the Multi→Single-AE model further compresses the 28-dimensional multi-AE latent representation into 7 dimensions to improve efficiency, as shown in

Table 8.

Table 9 provides a comparative summary of how each model compresses the original 55-dimensional input features. All models determine their latent dimensions using the same rule-based scheme, where the latent size is set to one-fourth of the input dimension (e.g., 55/4 ≈ 13) and constrained within a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 64 units. Following this rule, the single-AE model B2 produces a 13-dimensional latent vector. The multi-AE model B3 also applies the same compression rule but divides the input features into six groups, applies a separate 1/4-scaled encoder to each group, and then concatenates the six latent outputs. As a result, the final latent dimension becomes 28. Thus, both B2 and B3 follow an identical per-encoder compression principle, and the difference in latent size arises from architectural design rather than differences in compression policy. In contrast, B4 employs the most aggressive two-stage encoding process, ultimately reducing more than 87% of the original input dimension.

For each model, the training results and inference time were measured by separating the encoding and classification stages, and memory usage and throughput were also recorded. The main purpose of this experiment is to reveal the correlation between the structural complexity and performance of autoencoders and to determine a balance between computational efficiency and detection accuracy.

The second set of experiments (Set 2) for comparing resource usage and encoding efficiency analysis by model structure is conducted to quantitatively analyze the computational resource consumption characteristics of each model structure. For the four models (B1–B4) used in Set 1, the hardware resource utilization is measured separately for the encoding and classification stages. The metrics are measured based on a total of three criteria: CPU memory usage (RSS mean/max), GPU utilization (GPU utilization mean/max), and GPU memory usage (GPU VRAM mean/max). This experiment aims to analyze the impact of extending the autoencoder structure on system resource consumption and to evaluate the practical cost of increased structural complexity on computational efficiency.

The third set of experiments (Set 3) for comparing classifiers based on Multi-AE representation is conducted to compare the detection performance among various classifier models using the latent representation generated through the Multi-AE preprocessing step in the proposed B3 model as a fixed input. In this experiment, several machine learning-based classifiers, including SVM, are compared under the same input conditions. The models used are shown in

Table 10. This experiment aims to show that the proposed autoencoder-based latent representation is not dependent on a specific classifier structure and exhibits consistent detection performance across various learning algorithms.

The fourth set of experiments (Set 4) is conducted to verify whether the proposed model can meet Service Level Agreement (SLA) constraints in a 5G slicing environment. Measurements on an actual 5G network are not performed, but instead our inference results are compared by setting the SLA limit values from public literature as a reference. For the finally selected model (SVM-based Multi-AE structure), the mean/95% latency and throughput are measured while varying the inference batch size to 1, 8, 32, 128, and 512. Additionally, per-class latency is calculated to analyze real-time detection deviations based on attack types. The SLA baseline is as a reference, and whether the model meets the ultra-low latency and high throughput requirements is verified. This experiment aims to verify the inference efficiency and real-time responsiveness of the proposed model and to derive the optimal processing configuration based on batch size.

These four sets of experiments were designed to evaluate performance comparisons based on the structural differences in the autoencoder, the efficiency of computational resource consumption, the generalization performance related to latent representation, and the possibility of real-time detection under SLA constraints. Through this phased experimental design, the proposed model is structured to enable a comprehensive performance analysis that goes beyond simple accuracy evaluation, considering efficiency, reliability, and real-time performance in an actual 5G slicing environment.

5.4. Experimental Results

5.4.1. (Set 1) Comparison of SVM Performance by Autoencoder Structure

The detailed detection characteristics of each model were analyzed through the class-wise F1-score results in

Table 11. which represent the average values calculated over random states 41–45 for generalized performance evaluation. In the case of Benign, the F1-score remained above 0.99 for all models, showing very high stability. This data indicates that normal traffic has a structurally consistent pattern and is relatively less sensitive to changes in the autoencoder structure. For the Scan Attack class, all models showed consistently high precision in the range of 0.99–0.98, while recall remained around 0.76 across the board. Within this narrow performance band, the B3 model achieved a balanced score with a precision of 0.99, recall of 0.76, and F1-score of 0.86, demonstrating the most stable and consistent behavior among the models. Although scan traffic is structurally simple B3 maintains robustness by preserving essential features without excessive compression, resulting in highly reliable detection.

The TCP PUSH class exhibited the largest performance variation across models, and this is where the advantages of the B3 structure became most evident. B3 achieved a precision of 0.98, recall of 0.91, and an F1-score of 0.98, nearly matching the best performance of B1 while significantly outperforming both B2 and B4. In contrast, B2 dropped to an F1-score of 0.87 due to a sharp decrease in recall, and B4 degraded drastically to 0.67 because of aggressive two-stage compression. These results highlight B3’s ability to reduce dimensionality effectively while retaining fine-grained attack-specific patterns, making it the most balanced model between compression and detection accuracy.

For the TCP SYN class, all models consistently maintained excellent detection performance, since SYN flood attacks exhibit a highly repetitive and predictable connection-request pattern. As a result, the autoencoder structure has minimal influence on the classifier’s ability to distinguish this traffic type.

The TCP URG class showed the greatest instability overall, with precision varying from 0.65 to 0.80 and recall from 0.73 to 0.98 across models. Despite this variability, B3 produced the most effective and stable results, achieving a precision of 0.75, recall of 0.98, and an F1-score of 0.87, outperforming the other models. B4 dropped significantly to 0.71, and B2 achieved 0.82, showing inconsistent behavior. B3’s multi-AE architecture effectively captures the irregularity and low session consistency of URG traffic without introducing excessive compression, enabling superior detection stability.

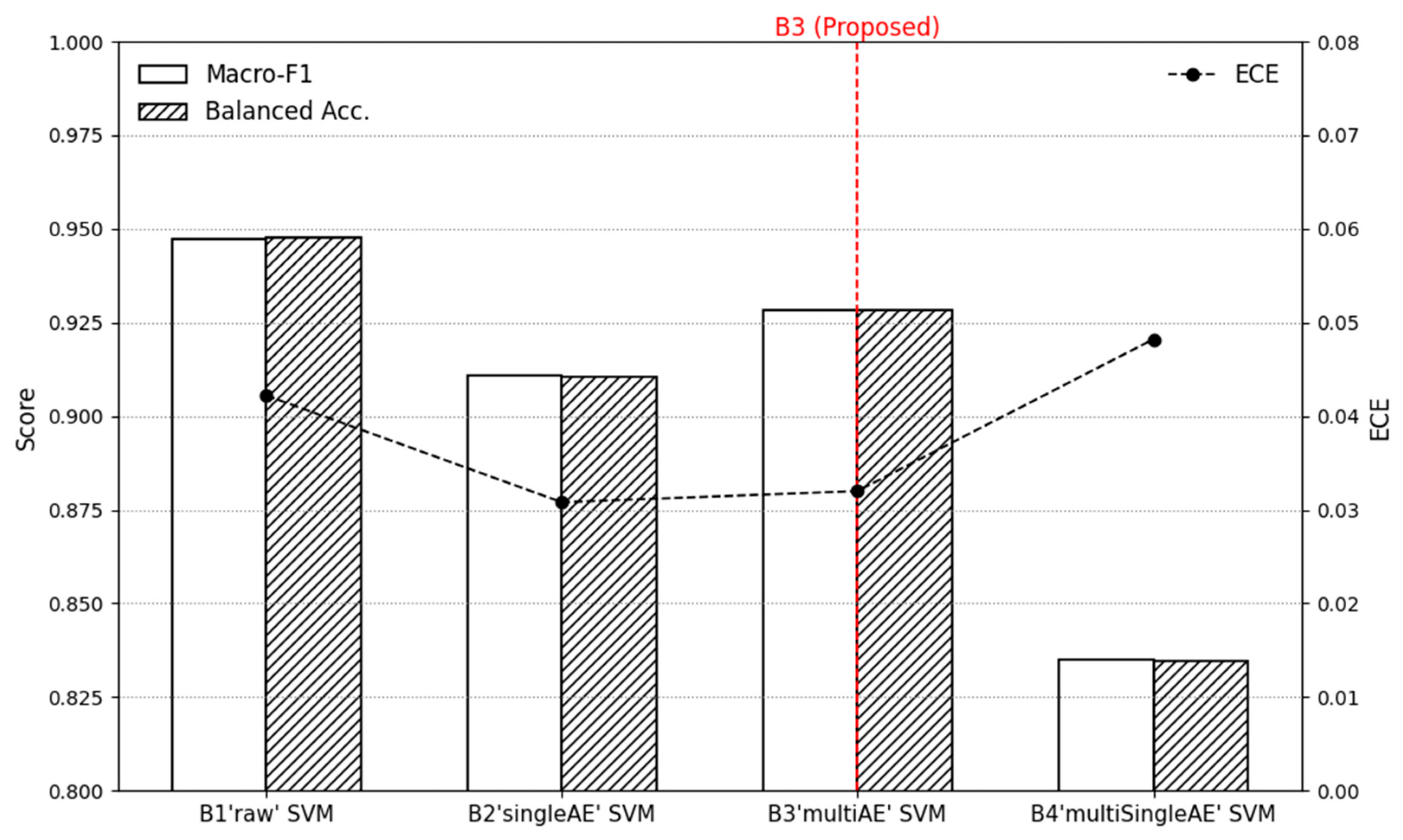

As shown in

Table 12 and

Figure 3, the performance differences across autoencoder structures become clear when evaluated under identical conditions. The B1 model, which uses raw features without any compression, achieved the highest scores overall, recording an accuracy of 0.95 and a macro F1-score of 0.95. This strong performance is expected, as the model directly leverages the full 55-dimensional feature space without any loss of information. The B2 model, which applies to a single autoencoder with a latent size of 13, showed a slight performance decrease compared to B1, with accuracy and macro F1 both around 0.91. This indicates that a single AE tends to capture only global patterns and is less effective in expressing class-specific feature variations. The B3 model, using the Multi-AE structure with six group-wise encoders and a concatenated latent dimension of 28, achieved moderately improved generalization compared to B2, showing consistent values across accuracy (0.93), macro F1 (0.93), and balanced accuracy (0.93). Its ECE score (0.03) also remained low, suggesting that the model’s probability estimates are more reliable. This improvement can be attributed to the Multi-AE structure independently learning each group’s characteristics, allowing the latent representation to capture finer inter-class distinctions without deviating from the unified com-pression rule. The B4 model, which performs the most aggressive two-stage compression, showed the largest performance drop, with accuracy and macro F1 decreasing to approximately 0.83. This result is consistent with the fact that B4 reduces more than 87% of the feature space, causing loss of detailed information that would otherwise assist in separating similar classes.

5.4.2. (Set 2) Comparison of Resource Usage and Encoding Efficiency Analysis by Model Structure

Table 13,

Table 14 and

Table 15 show the results for memory usage, utilization, and GPU memory occupancy of the proposed model (B3) and the comparison models.

Table 13 shows that the B1 model had the highest memory usage at approximately 6.1 GB, and the B2 model, which uses a single autoencoder, was also at a similar level of 5.9 GB, with no significant difference. On the other hand, the proposed model, B3, efficiently used memory with an average of 5.7 GB, despite employing a parallel encoder structure. This is interpreted as being because each feature group undergoes an independent encoding process, minimizing unnecessary parameter redundancy. Finally, B4 showed the lowest usage at 3.1 GB, but in the previous evaluation, it was confirmed that excessive compression resulted in loss of information, leading to a significant drop in detection rate. In 5G network slicing environments, such differences in memory usage are directly linked to slice-level resource availability and service isolation. Excessive memory consumption in one slice can reduce the available resources for other slices and may lead to degraded SLA performance.

In the GPU utilization analysis results of

Table 14, the GPU occupancy of all models was measured to be less than 10%, confirming stable operation is possible even in a real-time 5G traffic analysis environment. Specifically, the B3 model showed a maximum GPU utilization of 7% during the Learning Encoding 1 process, which was confirmed to be a temporary load due to parallel encoding operations. In terms of GPU efficiency, it is still confirmed to be a lightweight structure. Such low GPU load is crucial in slicing-based deployments, since shared GPU resources across slices are highly sensitive to temporary spikes. Excessive utilization may introduce scheduling delays and jitters, especially in URLLC-focused slices.

The GPU memory usage results in

Table 15 show that there was little difference between the models, and all models remained stable at around 390 MB. In MEC or slice environments where GPU memory is limited maintaining a small and stable memory footprint helps prevent resource contention and contribute to predictable real-time behavior.

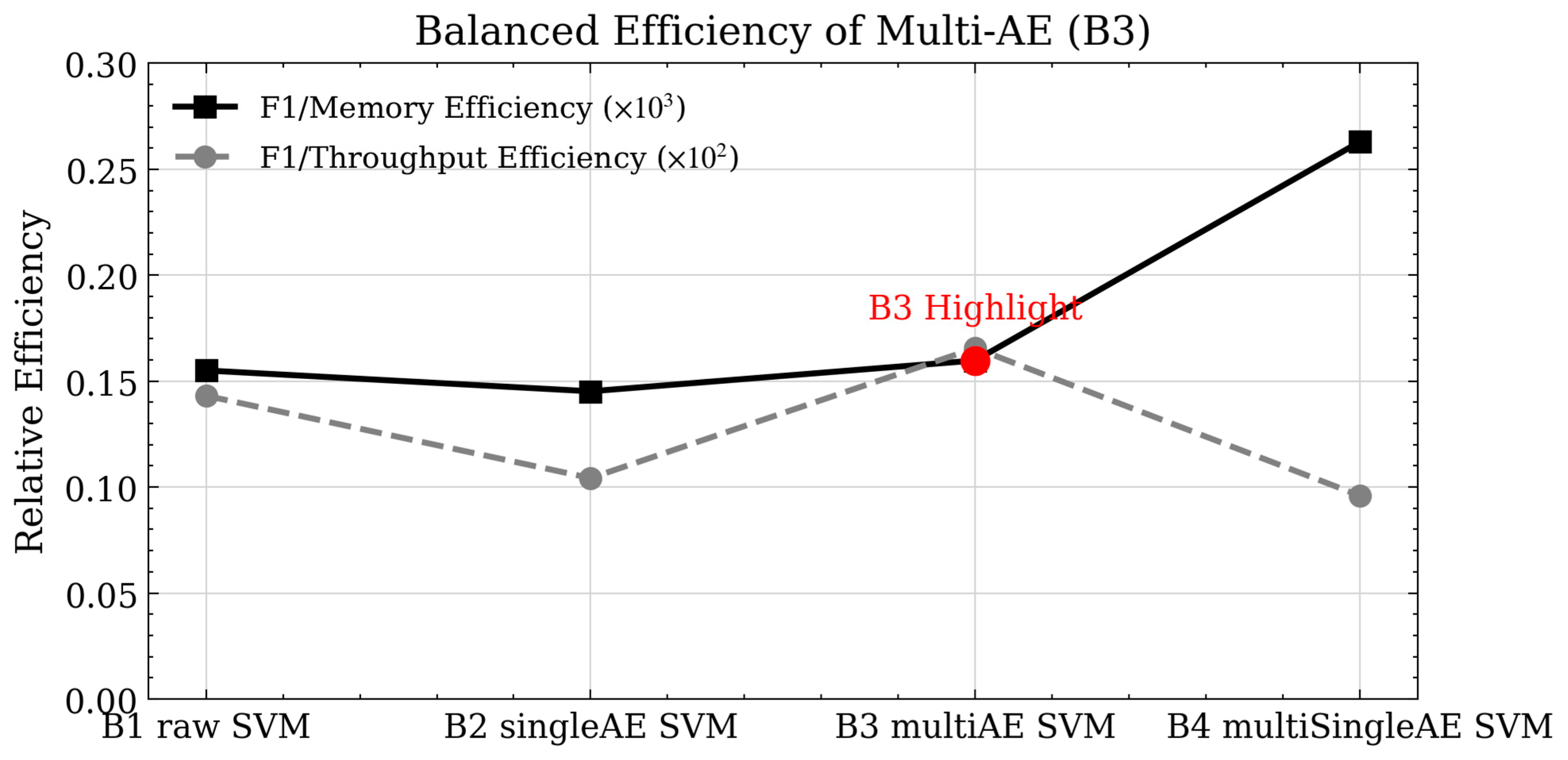

Figure 4 visually represents the results in the table, showing that the proposed model (B3) achieved the best balance between detection performance and resource usage. B3 achieved approximately 5% less memory usage than B1 while maintaining the same level of detection accuracy. It also gained the advantage of improved performance and reduced resource usage compared to B2. This balance is particularly important in slicing environments where resource overload in one analytic component can negatively impact other coexisting slices.

In summary, the B3 model based on Multi-AE has been proven to be a lightweight structure that minimizes hardware resource consumption while achieving improved information representation and generalization performance compared to a single AE.

5.4.3. (Set 3) Comparison of Classifiers Based on Multi-AE Representation

Set 3 compared the detection performance across various classifiers to verify the generalization performance of the proposed Multi-AE-based latent representation. This experiment analyzed performance differences based on classifier structures by using the features encoded through Multi-AE (latent features) as fixed inputs. All models applied the class_weight = “balanced” option to correct for class imbalance and performed isotonic calibration-based calibration to improve the reliability of predicted probabilities.

Table 16 shows the results of comparing the performance (accuracy, macro F1, balanced accuracy), prediction confidence (ECE), and resource efficiency (mean RSS) of each classifier. Most classifiers achieved accuracy above 0.95, confirming that the Multi-AE latent feature provides consistent detection performance across different models. Specifically, ensemble-based models (GB, HGB, XGB, LGBM) showed high detection performance around 0.96 and very low ECE (0.0028–0.0040), demonstrating that Multi-AE provides stable feature representation capabilities. On the other hand, the model using the proposed SVM model showed slightly lower values, but its resource efficiency was excellent compared to its model complexity. The mean RSS is around 5.8 GB, maintaining a lower memory footprint than most boosting models. In short, the Multi-AE-based feature representation method maintained consistent detection performance without being dependent on the classifier structure, and the proposed model achieved the best balance between performance and resources.

5.4.4. (Set 4) Comparison of SLA Constraints Met by Model

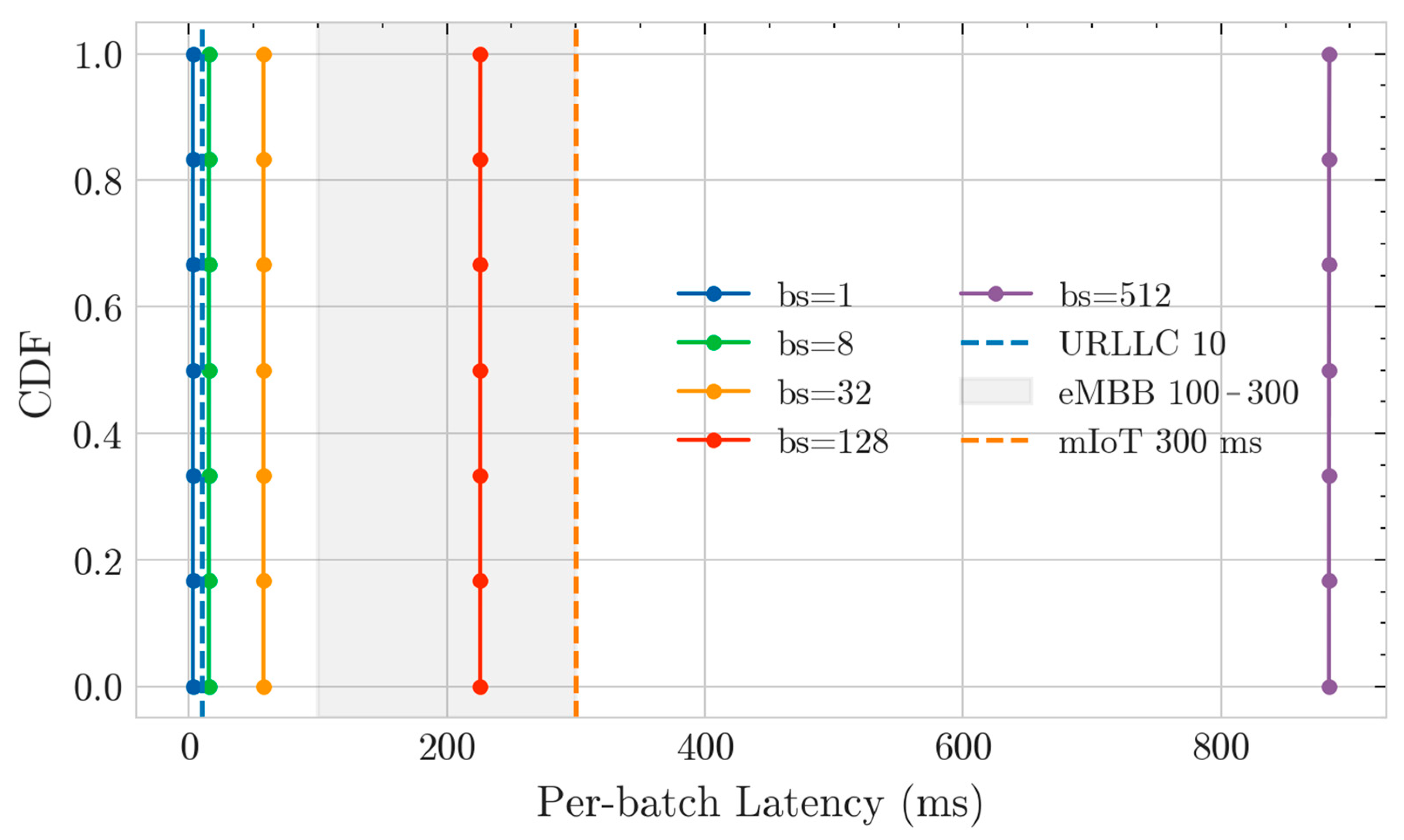

Figure 5 shows that the latency distributions for all batch sizes fall within the SLA region. Specifically, in the bs ≤ 128 range, there is a low latency distribution that meets the 10 ms URLLC criteria. This means that the proposed Multi-AE encoding generated a lightweight latent representation, thereby reducing inference time.

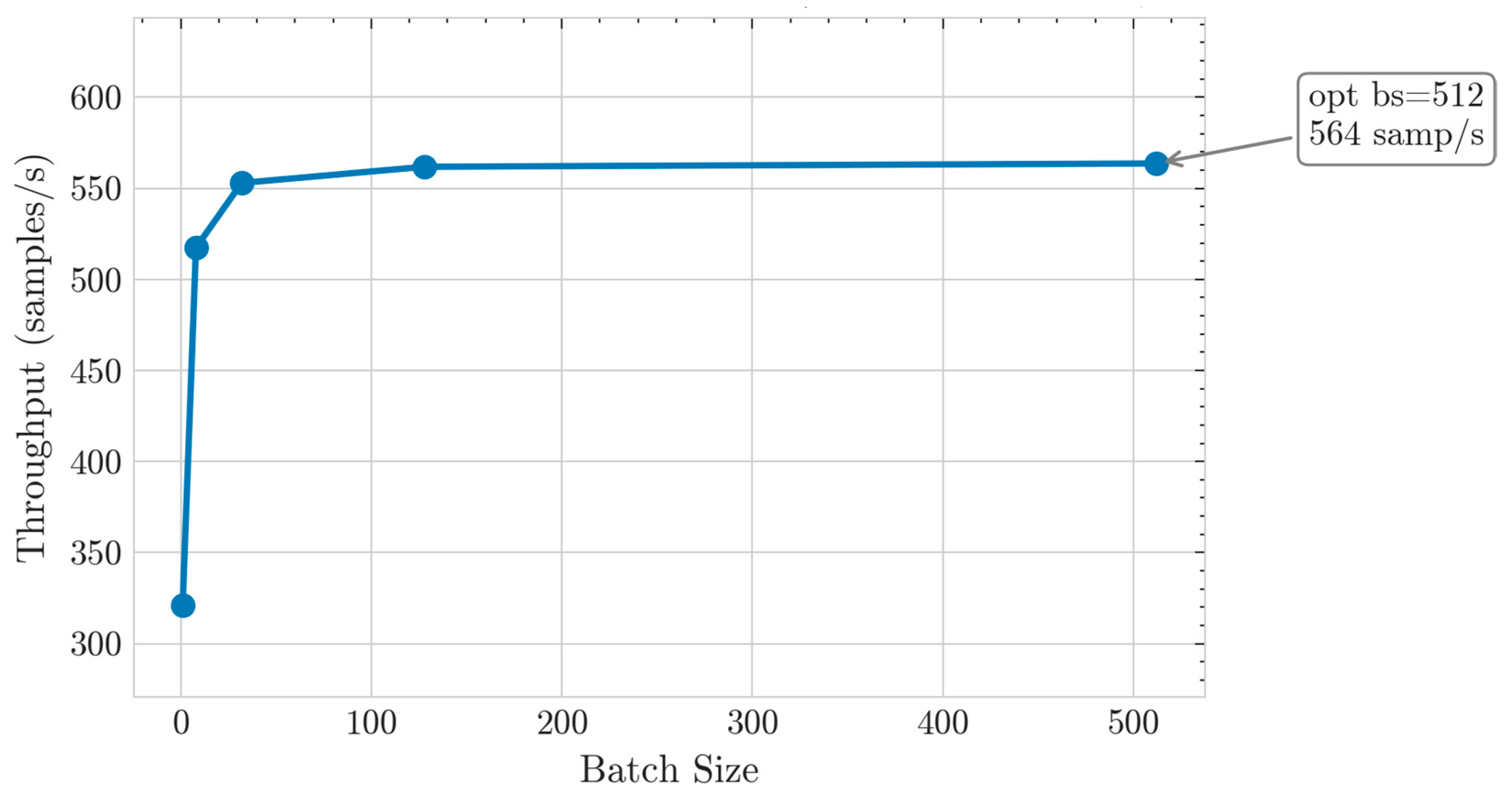

The throughput curve in

Figure 6 increases exponentially in the bs (batch size) = 1–8 range, saturates from bs ≥ 128, and achieves a maximum throughput of 564 samples/s at the optimal batch size (bs = 512). This indicates the point where the balance between inference efficiency and latency is optimal, making it a suitable operating point for real-time eMBB services or industrial sensor network environments.