1. Introduction

In the context of increasing competition, manufacturing enterprises must implement advanced quality management mechanisms that serve a dual purpose: ensuring compliance with customer requirements and enhancing organizational resilience to operational and strategic risks. High production risk arises from factors that disrupt processes, leading to reduced efficiency, increased costs, and decreased competitiveness. In response, legal requirements and standards, such as ISO 9001 [

1], have been introduced, which in 2024 had been implemented by more than 1.47 million companies worldwide [

2]. This standard emphasizes risk-based thinking; however, it does not specify methods or documentation for risk management and does not consider the specific characteristics of production. Therefore, the development of new models and methods for risk assessment tailored to the particularities of manufacturing enterprises is necessary. While strategic risk can be analyzed using similar methods across different organizations, production risk has a distinct nature and stems, among other factors, from technological and organizational constraints as well as the presence of stochastic disruptive factors (so-called risk factors) in the manufacturing process. These risk factors most often lead to extended order fulfillment times or production losses [

3].

This issue is particularly critical in mass production systems based on production line structures, which are widely used in the mechanical, wood, and food industries [

4]. Addressing this problem requires a thorough understanding of the relationship between the structural characteristics of the production line and production risk, which arises at various stages of product manufacturing [

5,

6,

7]. The sequential structure of production lines makes them highly sensitive to disruptions, and any extension of the processing time at a single stage can generate a cascade effect, resulting in delays further down the production flow [

8,

9,

10,

11]. These factors are especially critical in batch and small-series production [

12,

13], where even minor deviations can cause order delays, increase work-in-progress (WIP), and reduce resource utilization efficiency [

14]. Therefore, minimizing the impact of disruptions requires an in-depth understanding of the relationships between the structural features of the production line and the production risk arising at various stages of manufacturing [

5,

6,

7].

In such conditions, traditional deterministic planning methods prove insufficient, since they do not take into account the random nature of the duration of technological operations and their interaction at the level of the entire production line [

15].

Modern methods of optimizing production planning are based primarily on deterministic models in which the execution times of operations are assumed to be constant. However, in real conditions, the production process is subject to the influence of many random factors, such as equipment failures, material shortages, deviations in the quality of raw materials, and the human factor [

16,

17]. This creates a need to develop stochastic models that can adequately describe the behavior of the system and predict probabilistic deviations from planned deadlines [

7].

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have shifted from deterministic models to probabilistic and simulation-based approaches. For example, Li et al. [

18] reviewed stochastic programming methods in process industries, emphasizing the limitations of deterministic production planning under uncertainty. Similarly, Huang et al. [

19] proposed a trajectory-accuracy reliability analysis method that incorporates mixed uncertainties to assess the reliability of sequential production processes. However, many of these studies focus either on the probabilistic modeling of operation times or on trajectory analysis, without simultaneously considering the structural topology of linear production systems—such as the number of operations, batch size, and inter-stage dependencies—together with disruption-related risk factors [

20]. This research gap constitutes the motivation for the present study, which integrates the structural characteristics of a linear production system with probabilistic operational state features.

This study aims to develop a model for assessing production risks in a linear system, taking into account the statistical characteristics of operating time and the structure of the technological route. The model is based on a spatial description of the processing trajectory of a batch of products using dimensionless parameters, which ensures the universality and scalability of the approach. Particular attention is paid to the analysis of the dependence of the average processing time of a part on the batch size and the number of operations, as well as the introduction of a risk function that allows for a quantitative assessment of the probability of violation of production deadlines.

The relevance of the conducted research is determined by the need to increase the reliability of production planning in conditions of uncertainty characteristic of small and large-scale production. The novelty of the work lies in the integration of the spatio-temporal description of technological processes with a probabilistic model of equipment downtime, which allows for more accurate forecasts and management of production risks at the planning stage.

2. Risk Assessment in Production Systems—Limitations of Classical Methods and a Trajectory-Based Approach

The specificity of production processes requires a different approach to risk than in the financial domain, where a higher level of investment risk is generally associated with the potential for greater returns. In manufacturing, due to technical and technological constraints, it is not possible to expect outcomes beyond the capabilities defined by the adopted technology or organizational structure. Therefore, production risk should be considered in the context of unachieved production plans, which most often manifests in two forms: time losses resulting from prolonged processing of product batches compared to the plan, and quantitative losses related to the failure to produce a specified number of products within the planned time [

3,

21].

In the literature, production losses are typically analyzed in two dimensions. The first concerns machine utilization efficiency, measured by the Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) index, where total losses result from downtime, reduced performance, and quality losses [

22]. The second dimension encompasses a broader perspective related to the failure to achieve the intended goals of the production system, which may be temporal, quantitative, financial, qualitative, or efficiency-related [

23,

24]. In practice, companies most often rely on criteria defined in the production plan, which relate to the timeliness of order fulfillment as well as the quantity and quality of manufactured products.

Analyzing production risk requires considering both the system structure and the type of operations performed, as well as the nature of factors disrupting the technological process. In linear systems, the cascade effect is particularly significant—any extension of processing time at one stage causes delays at subsequent stages, resulting in both time and quantity losses. In this context, modern organizational approaches, such as Lean Manufacturing, emphasize the need to minimize waste through proper flow planning and shortening order fulfillment times, which directly improves delivery reliability and customer satisfaction [

25].

Despite the widespread implementation of quality management systems compliant with ISO 9001:2015 [

1], the risk-based approach introduced by these guidelines remains very general and does not provide tools specific to production processes [

24]. The standard requires identification and management of risks but does not provide methods for quantitatively assessing the probability of disruptions. Consequently, companies most often rely on general qualitative techniques, such as Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA), which—though useful—are simplified and do not reflect the complexity of production systems [

26,

27]. These methods are static, do not consider the spatio-temporal trajectory of product batches, rely on expert judgments or average values, and do not allow analysis of statistical properties of operation times. Their limitations also include a lack of adaptability to dynamically changing production conditions and limited integration with operational planning [

27,

28].

The literature increasingly emphasizes the role of probabilistic approaches, which account for the randomness of operation times and disruptions, as well as the interdependencies between consecutive production stages. Such models enable quantitative assessment of the risk of schedule violations, allowing for proactive risk management rather than reactive measures [

25,

29,

30]. The probabilistic approach makes it possible to predict, with a defined level of confidence, the likelihood of disruptions affecting the timely fulfillment of the production plan. Compared with existing stochastic models [

7] and trajectory-based analyses [

25], the proposed approach unifies both perspectives by representing the production line in a dimensionless state space that simultaneously captures the probabilistic and structural dependencies of the system. The key contribution of this study, in contrast to previous research, lies in its ability to assess production risk as a function of batch size. This approach provides a clear and quantitative understanding of how the magnitude of production risk changes within the same production line depending on the type of production system—including single-piece, small-scale, medium-scale, large-scale, and mass production. The proposed model not only extends the classical probabilistic representation of production lines but also introduces a practical framework for analyzing production risk sensitivity with respect to production type, offering valuable insights for planning and mitigating risks in manufacturing systems.

The key challenges addressed in this study arise from the complexity of assessing production risks in modern manufacturing systems, where process dynamics are influenced by random fluctuations in operation times, machine performance, and resource availability. Traditional deterministic or expert-based methods (e.g., FMEA) are limited in accounting for these uncertainties because they rely on static estimates and do not reflect how local disturbances propagate through successive process operations. Existing stochastic approaches, although they implement probabilistic modeling, often do not take into account the structural characteristics of production lines, such as the order of operations, flow synchronization, and inter-operation dependencies, which are crucial for predicting cascading delays and identifying bottleneck migration. In addition, there are no quantitative indicators linking production risk to batch size or production type (single-piece, small-scale, medium-scale, large-scale, or mass production). The present study attempts to address these issues by developing a unified stochastic model that combines a probabilistic description of process variability with a spatio-temporal representation of the production line structure. This integration enables a systematic assessment of production risks, allowing the identification of the dynamics of reliability indicators depending on batch size and production scale.

In this context, developing risk assessment models that account for the technological line structure and statistical properties of operation times is particularly justified. The essence of this subject-technological representation is the construction of an individual trajectory for each part along its technological route. The trajectory is determined analytically as the solution to a system of equations describing the sequence of technological operations. This analytical formulation distinguishes the proposed method from discrete-event simulation (DES), where system behavior is shaped by stochastic event scheduling. Within the subject-technological approach, the trajectories of individual parts are calculated sequentially and do not intersect; the trajectory of the current part forms a constraint for calculating the trajectory of the next part. This sequential construct defines the evolution of part states in the technological space. The time slice reflects the distribution of part states along the production line at a given point in time, while the operational slice characterizes the dynamics of inter-operational buffers and material flows between successive operations. This analytical representation is conceptually reminiscent of system dynamics approaches, reflecting feedback loops and cumulative effects in the production flow. Compared with queuing theory models, which typically assume stationary flow parameters and focus on statistical estimates of waiting times or service rates, the proposed approach explicitly models part trajectories, taking into account finite buffer capacities and technological operation interdependencies. This allows for the description of transient production conditions and dynamic congestion phenomena, which are quite difficult to account for in traditional stationary queuing models. The use of a dimensionless state space serves as a normalization tool that unifies the key parameters of a production line, ensuring scalability and comparability between systems of different capacities. Although this study does not address similarity criteria for production systems, the proposed normalization approach provides a conceptual foundation for formulating similarity criteria for production lines in future research. The combined use of a subject-technological description and a dimensionless state space enables the construction of analytically flexible and structurally consistent models of manufacturing systems, offering an alternative to risk analysis, bottleneck identification, and calculation of part flow dynamics along a process route.

An approach based on a spatio-temporal description of the processing trajectory of product batches is recommended, where each stage of the process is represented using dimensionless parameters. This ensures the universality and scalability of the model and allows analysis of the relationships between the average processing time of a batch, its size, and the number of operations. Integrating the trajectory description with a probabilistic model of disruptions enables the definition of a risk function, allowing quantitative assessment of the probability of production deadline violations. In the following sections, a risk assessment model for linear production systems will be proposed, incorporating these elements and extending classical approaches used in industrial practice.

3. Problem Statement

A production system with a linear structure is investigated. The production line comprises

technological operations, arranged sequentially one after another. The state of a batch of

N parts that are at different stages of processing is determined by the set of states of each of the

N parts. The technological operation causes a gradual change in the state of the part. As a product moves through the technological operations, the initial resources are transformed into finished products, which are described by the production function of the process equipment [

31,

32].

To formalize the technological process of the part, the parameters

and

are introduced, which determine the state of the part at a given moment of time

, where

is the average time of technological processing of a part at time

, characterizing its state in the technological route;

is the processing time of a part at time

. Then the state of the part after the

-th technological operation is characterized by the value of the technological processing time:

where

is the average execution time

of the

-th technological operation;

is the total technological time for product manufacturing.

To ensure the generality of the analysis and eliminate the influence of dimensional factors such as absolute time scales and production rates, the process description is further expressed in terms of dimensionless parameters [

25]:

where

is the dimensionless time coordinate corresponding to the normalized process time;

is the average dimensionless technological processing time of a part, characterizing its position along the technological route;

is a dimensionless parameter characterizing the processing time of a part during a technological operation at the current moment in time;

This approach enables the comparison of different production systems under unified conditions and facilitates the development of scalable mathematical models.

The state of the part during processing at the -th technological operation at a given moment in time is determined by a point in the state space . The sequence of such points corresponding to successive time moments forms a trajectory in this space, which reflects the evolution of the part’s state throughout the technological process.

The time interval required to produce a batch of

N parts for a deterministic production process is determined by the expression [

25]:

The technological operation parameter represents the average dimensionless processing time of a part at the -th technological operation. Each technological operation parameter is normalized with respect to the total processing time along the entire technological route, so that the sum of all average dimensionless times equals 1. This normalization allows comparison of production lines with different numbers of operations or time scales.

The average processing time for a part for a deterministic production process, based on the number of parts in a batch, is calculated as follows:

For a qualitative assessment of the processing time of a part, averaged over the number of parts in a batch, the value is taken as

. This estimate corresponds to the case of a synchronized production line

and follows directly from the expression (2):

The processing time of a part decreases with an increase in their number in a batch and is within a range of values , and depends significantly on the size of the batch. The ratio between the maximum and minimum values of the processing time of the part is equal to the number of technological operations in the technological route (5).

Thus, even under the conditions of a deterministic model, where there is no randomness in the duration of technological operations, the processing time

of a part turns out to be dependent on the batch size and the number of technological operations. This indicates the presence of internal structural factors that influence the efficiency of the production process. In real production conditions, changes in batch size can have a significant impact on the nature and extent of the consequences associated with production risks. The analysis of the relationship between batch size, process flow structure, and production losses associated with production risks becomes a key element for optimizing production planning [

33,

34]. This issue is discussed in detail in this research.

4. Materials and Methods

The technological description of the production line is used as a basis for modeling production risks in this research. With this description, the state of the production system is determined by averaging the states of individual parts of the batch in the technological space

[

35]. The states of the

-th part at arbitrary moments in time

are specified by points

in the technological space, the set of which forms a technological trajectory in accordance with the technological process of parts production. This technological trajectory is the implementation of the stochastic process of manufacturing a part as it moves along the technological operations of the technological route. The processing time of a part during a technological operation is a random variable, the value

of which is determined by a set of production factors. The set of main production factors that determine the production process for the part during a technological operation is presented in

Table 1 and is discussed in detail in the research [

36]. The model of a technological operation based on the specified set of production factors assumes that at the

-th technological operation, the part can be in one of the

-th states presented in

Table 1 with the probability of the state

. On the probability space

, the random variable

is introduced to describe the operational state of the part during the

-th technological operation. The parameter

denotes the set of all possible outcomes for realizations of operation states;

is the σ-algebra of measurable events,

.The probability that the part is in state z is given by

, where

. Thus, the random variable

defines the stochastic behavior of the part as it transitions between possible operational states listed in

Table 1.

The predicted time during which a part can be in the

-th state at the

-th technological operation is determined on the basis of the statistical characteristics of

Table 1, represented by the distribution density

with the mathematical expectation

and standard deviation

. Based on the data of statistical characteristics and known distribution densities

, the distribution density

of a random variable

is calculated, characterizing the processing time of a part at the

-th technological operation. According to the law of total probability, the overall distribution density of the processing time for the

-th technological operation can be expressed as follows:

The random variable

is determined solely by production factors

Table 1. When modeling the movement of a batch of parts along a process route, the following restrictions are introduced: (1) the FIFO rule is used when processing parts; the production line is empty before processing a batch of parts and is not prefilled with parts from the previous batch; (2) there are no containers for inter-operational backlogs on the production line. The first limitation is introduced in order to exclude intersections of technological trajectories of parts during their processing along the technological route. The second limitation allows us to exclude the effects of interaction between batches of parts. Since the technological trajectories of the parts do not allow intersection, the technological trajectory of the part of the previous batch limits the technical trajectory of the first part of the batch under study, which leads to distortions of the research results. The third limitation allows us to exclude effects associated with the size of inter-operational bunkers. If the size of the bins for inter-operational backlogs is large enough, then when processing a batch of parts, there is a possibility that the bins will not be filled with parts. A gradual increase in the number of parts in a batch leads to the fact that individual bunkers will be filled with parts, while others will be unfilled or even empty of parts. In order to exclude such side effects, a third limitation was introduced. The presence of constraints allows us to simplify the modeling of the production line, while focusing the main research emphasis on solving the problem posed in this research.

The introduced constraints correspond to an idealized representation of a continuous linear production line operating under the FIFO rule. This approach was adopted in the present study to eliminate the influence of factors unrelated to batch size—such as the mixing of different batches, prioritization of parts from various lots, and the size of interoperational buffers—on the estimation of production risk. Although the current study considers only one type of part, where all items undergo identical technological operations and the first constraint could potentially be relaxed, it has been maintained to ensure the uniqueness of technological trajectories for all parts within the batch. This provides a consistent snapshot of the system state for each realization of the production process. In real manufacturing environments, however, interoperational buffers, partially loaded lines, or overlapping batches may exist. Relaxing these constraints would increase the correspondence with real-world conditions but would also introduce feedback and queuing effects between operations of different batches processed on the same equipment. This, in turn, would significantly complicate the model and introduce additional variability when evaluating the dependence of production risk on batch size. Thus, the current assumptions correspond to the fundamental case of a synchronized production line, allowing us to focus on analyzing the impact of batch size (and, consequently, the type of production system) on the magnitude of production risk. At the same time, future extensions of the model may include buffer capacities or overlapping batches as additional parameters to more accurately represent specific industrial configurations.

Considering these limitations, the equations of the process trajectories of the batch parts for the production line model take the form:

where

denotes the index of the technological operation, and

represents the index of the part within the batch. The variable

corresponds to the start time of processing the

-th part at the

-th technological operation, while

characterizes the stochastic processing time of a single

-th part at

-th operation, determined by the random variable, according to the probability distributions defined in

Table 1. The term

specifies the completion time of the same part at the previous operation. This system of relationships allows sequential computation of the technological trajectories for all parts within the batch under the given assumptions and with initial conditions that specify the start time of processing of the

-th part in the first process operation:

In the considered simplified model of the production line, the trajectory of the part is approximated by a set of points

, identifying the start time of processing of the

-th part at the

-th technological operation. The processing time of a batch of parts is defined as the time interval between the starting point of the first part of the batch at the first technological operation and the finishing point of processing the last part of the batch at the last technological operation:

In accordance with this, the average manufacturing time of the final product for a batch of

N parts is determined based on the estimated processing time of the batch of parts

:

This time is used below to assess the impact of production risks on the overall production time of a batch of products. The points corresponding to the time of completion of the processing of the part in the technological operation are omitted in the presented model due to the fact that, for solving the given problem, this information will not lead to an increase in the accuracy of calculations of the production time of a batch of parts, but only complicates the computational process. The system of Equation (7) contains a third limitation, which is defined by the following inequality . Since the production line does not contain inter-operational bunkers, the value of the start time of processing of the -th part is clearly limited only by the value of the start time of processing of the -th part, and not by parts with a lower number, which simplifies calculations and makes the qualitative analysis of the problem simpler. Provided that , the value of the processing time of a batch of N parts takes a simplified form, .

For a deterministic model of a linear production line, the system of Equation (7) with initial conditions (8) has a solution that allows expression (9) to be presented for calculating the processing time of a batch of parts in the form of formula (3). This expression is used in this study as a basis for assessing production losses associated with production risks of downtime of process equipment.

5. Results

To analyze the influence of the batch size on the specific time of manufacturing the final product, a process route is examined containing seven consecutive process operations (

Table 2). During technological processing at the

-th technological operation, the part is in one of the

-th states during a random time interval. The time that the process equipment stays in the

-th state is characterized by the mathematical expectation

and the standard deviation

for

and

for

, the values of which are determined experimentally and correspond to industry standards for the production of single-leaf windows.

The probability that the equipment is in the

-th state is calculated based on the processing of experimental statistical information and is presented in

Table 3. The probability parameters

for each process operation (E1–E7) were derived from empirical observations of process performance on a production line processing batches of various sizes (production orders from 3 parts to 70 parts per batch were analyzed). Each operation was monitored for 127 process cycles over a twelve-month observation period. Operating states (

) were defined based on machine log data and operator reports. In some operations, specific states were not observed within the recorded sample; such cases are marked as “–” in

Table 3. This notation indicates the absence of data rather than a probability value of zero. To check the adequacy of the sample data, the

goodness-of-fit test (

) was used.

Considering the dimensionless parameters (1), the parameters of technological operations from

Table 2 are presented in dimensionless form, which are used to model the technological process of processing parts,

Table 4. The use of dimensionless parameters (1) is the first step towards constructing a theory of similarity of technological processes. The dimensionless time of manufacturing one part in accordance with the technological route for arbitrary production lines is equal to one, which is convenient for conducting a comparative analysis of linear production lines.

The throughput of a production line using dimensionless parameters (1) is estimated by the value , which is inversely proportional to the number of technological operations in the technological route. This assessment is more accurate given the higher level of synchronization of technological operations on the production line. Thus, the introduction of dimensionless parameters (1) allows, in the first approximation, to determine the conditions for a comparative analysis of production lines, when the results obtained for one production line can be used to analyze another production line. It should also be noted that the addition of process operations together with measures to synchronize the production line leads to an increase in the throughput of the production system. Thus, an increase in the productivity of a production line can be achieved both by adding parallel technological operations and by adding sequential technological operations, for example, by dividing a technological operation with a long execution time into two sequential technological operations. The separation of one technological operation into two results in the parallel execution of two parts within one generalized technological operation, which was divided into two consecutive technological operations.

Using the statistical characteristics of the technological equipment being in one of the

-th states from

Table 3 and

Table 4, the distribution density

of the processing time

is calculated for each technological operation. When constructing the distribution density

of the processing time

of a part in a technological operation, a model is used that assumes that the value

is the time interval between two events of the equipment entering the state

. The results of the modeling of the part processing time are presented in

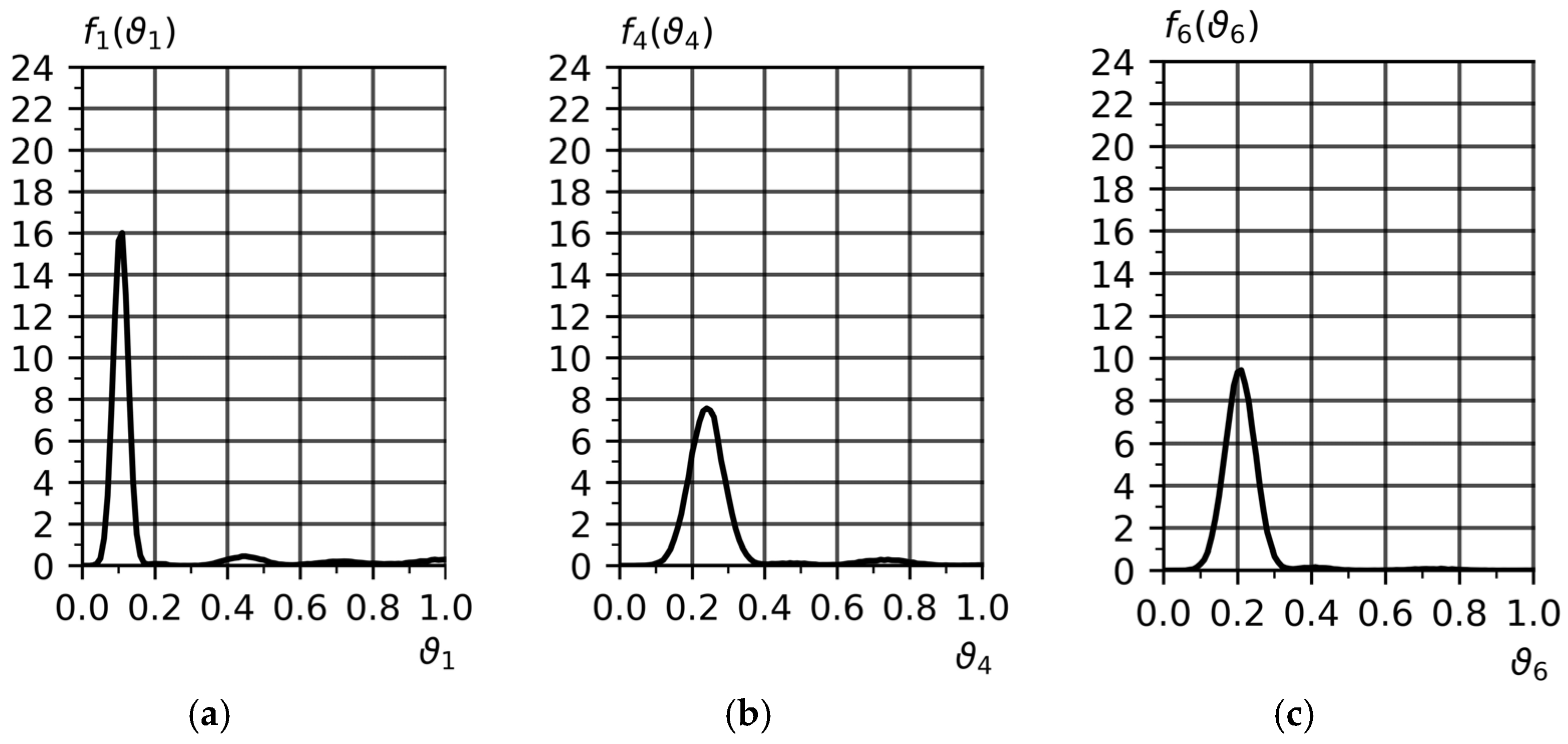

Figure 1.

The distribution density

of the processing time

of a part for a technological operation is a multimodal function. Each mode of this function is associated with the probability of finding the process equipment in the

-th state,

Table 4.

Figure 1 clearly demonstrates that the main mode of operation of the production line is the state of the workstation (

Table 1 and

Table 3,

) for each technological operation. The remaining modes of the distribution density

determine the probability of occurrence of effects associated with production risks of non-fulfillment of a production order within the agreed time frame.

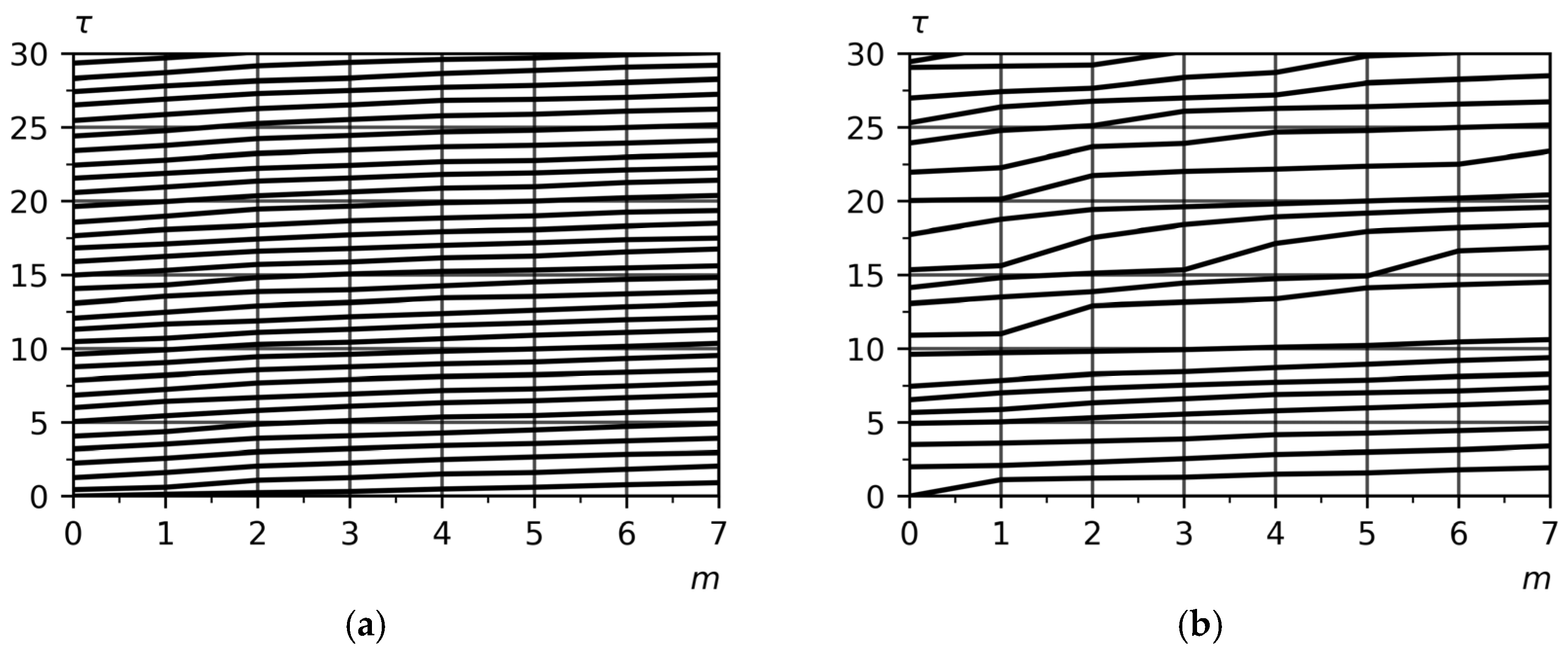

The solution of Equation (7) for a batch of

N parts is shown in

Figure 2. For a stochastic process of processing a batch of products, one of the implementations of the stochastic process is shown. Each plot shows samples of the motion trajectories of every fourth part, such that the trajectories of each part are distinguishable from each other. The graphs demonstrate the fulfillment of the condition for the movement of a batch of products along a linear production line that does not provide for the presence of inter-operational backlogs. As emphasized above, this option is, on the one hand, simple for solving the system of Equation (9), and on the other hand, it clearly demonstrates the process of interaction of parts with each other during their processing in accordance with a given technological process.

The trajectories of the movement of a batch of

N parts shown in

Figure 2 allow us to provide a graphical solution to Equation (9) for estimating the production time of a batch of parts. Each implementation of the stochastic process of manufacturing a batch of

N products can be assigned a value

in accordance with Equation (9). The solution of Equations (7) and (8) is obtained by sequentially simulating the trajectories of parts along the process flow. For each realization, random processing times

are generated according to the probability density functions

corresponding to each process operation (

Table 3). The simulation begins with the initial condition

, after which recurrence relations (6) and (7) are iteratively evaluated for all parts

and technological operations

. The resulting set of initial times

defines one realization of the stochastic batch production process. Repeating this procedure for multiple realizations (typically

) allows for estimating the statistical distribution of the total batch processing time

and constructing the corresponding distribution function

of the processing time

of a part (

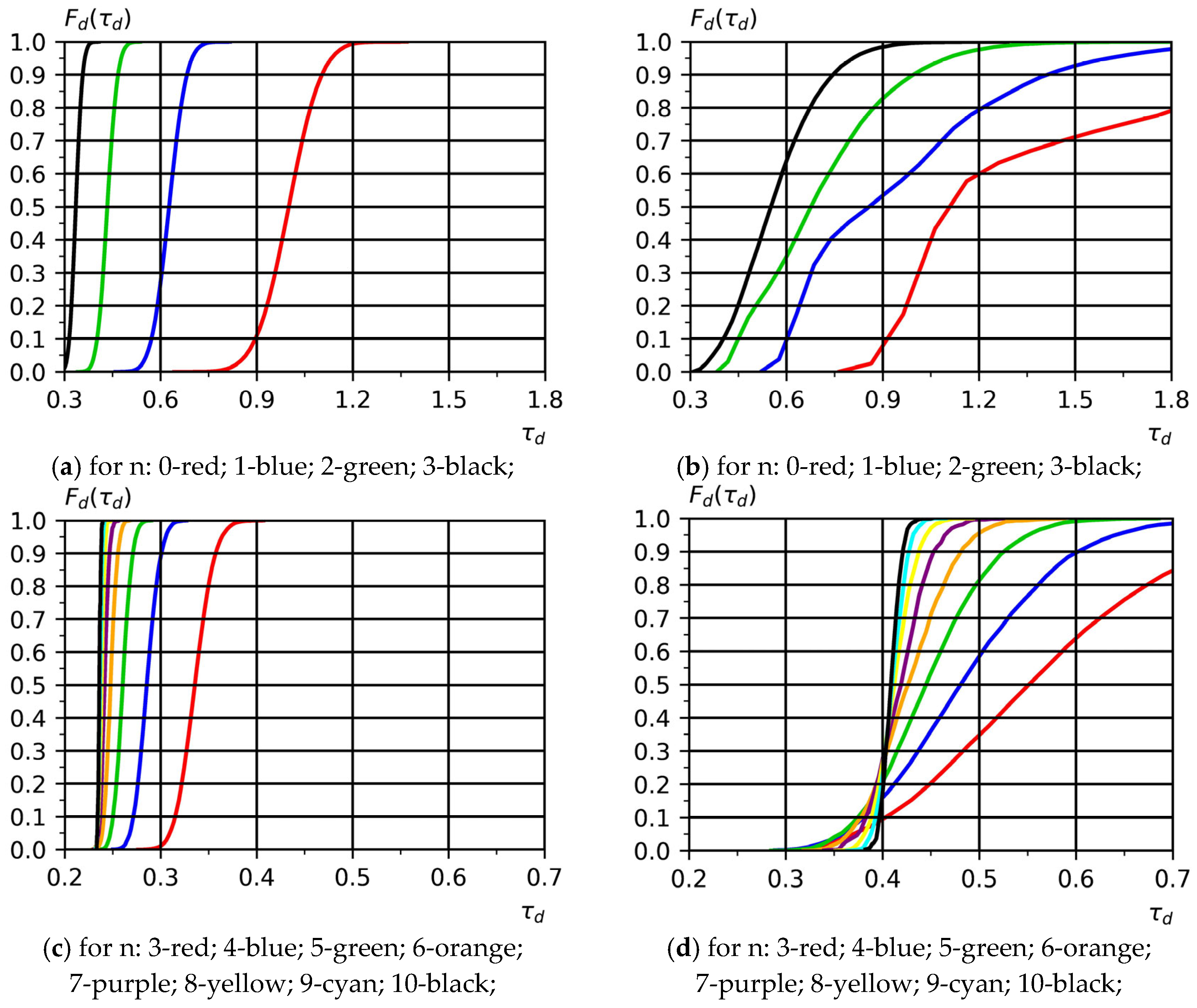

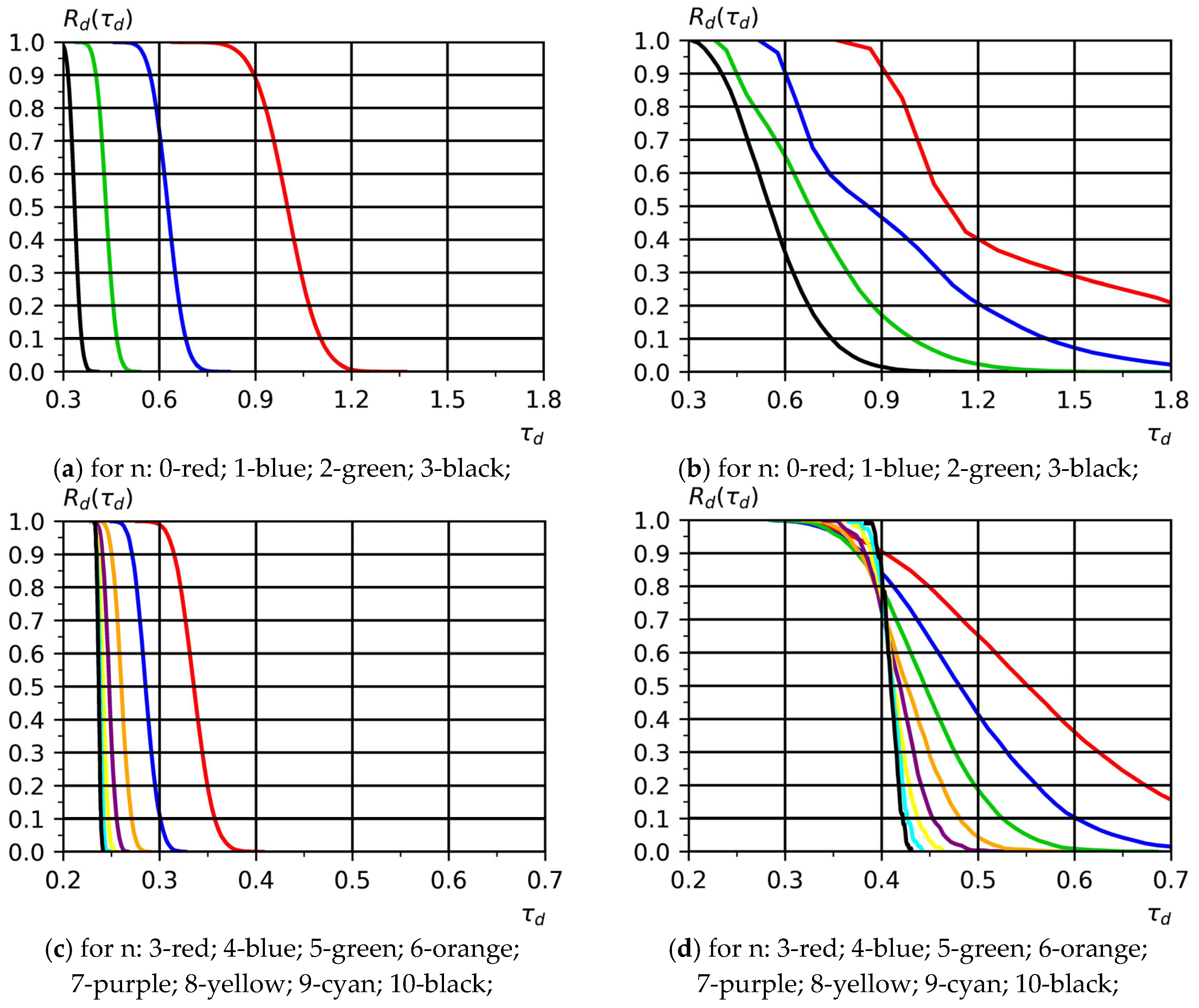

Figure 3). This hybrid approach, combining analytical recurrence equations with simulation of random parameters, ensures numerical reproducibility and provides a consistent basis for statistically estimating risk functions. A typical case of small-scale production is shown in

Figure 3a,b. Here, in the direction from right to left, the distribution function

is presented for batches containing

N = 2

n parts (n = 0: red line; n = 1: blue line; n = 2: green line; n = 3: black line). The case of parts processing in the absence of equipment downtime associated with production risks (

Figure 3a,

= 0, z = 1…6) and the case when there is equipment downtime associated with production risks (

Figure 3b,

> 0, z = 1…6,

Table 3) are considered. For the case of small-scale production, an increase in the batch size of parts leads to a decrease in the average processing time

of the part, mainly due to the first term

in expression (4), which correlates with the time required to process one part. This interval is determined by the time interval from the moment the product starts the first technological operation to the completion of its processing. The presence of inflection points in

Figure 3b indicates the migration of a bottleneck during the processing of a batch of products due to the emergence of production risks leading to downtime of the process equipment. In contrast, the distribution function curves

of the part processing time shown in

Figure 3a have only one inflection point, corresponding to a unimodal distribution function of the part processing time

.

A typical case of serial and large-scale production is demonstrated in

Figure 3c,d. In the direction from right to left, the distribution function

is presented for batches containing

N = 2

n parts (n = 3: red line; n = 4: blue line; n = 5: green line; n = 6: orange line; n = 7: purple line; n = 8: yellow line; n = 9: cyan line; n = 10: black line). The case of processing in the absence of equipment downtime associated with production risks (

Figure 3c,

= 0, z = 1…6) and the case in the presence of equipment downtime associated with production risks (

Figure 3d,

> 0, z = 1…6,

Table 3) are considered. With a further increase in the batch size of parts, the contribution of the first term

in expression (4) decreases for serial production and becomes insignificant for large-scale production. Two effects are observed in the analyzed graphs. The first effect is the shift of the distribution function

to the left, associated with a decrease in the average processing time

of the part in accordance with the decrease in the contribution of the first term in expression (4). The second effect demonstrates a gradual clockwise rotation of the distribution function

associated with a decrease in the standard deviation

due to the effect of increasing the batch size of parts.

6. Discussion

The variable is defined as the ratio of the production time to the batch size. Since the value includes the sum of independent processing times of the -th part at the -th technological operation , it can be assumed that for large , the distribution of the random variable will tend to the normal distribution law with mathematical expectation and standard deviation . This results in shifting and compression of the distribution function for different values of N. The obtained values can be used as an approximation of the distribution function . To calculate precise values, it is necessary to take into account the limitations associated with the interaction of technological trajectories of movement in the technological state space : technological trajectories of parts do not intersect, the production line before processing a batch of parts is empty and does not contain bunkers for inter-operational backlogs.

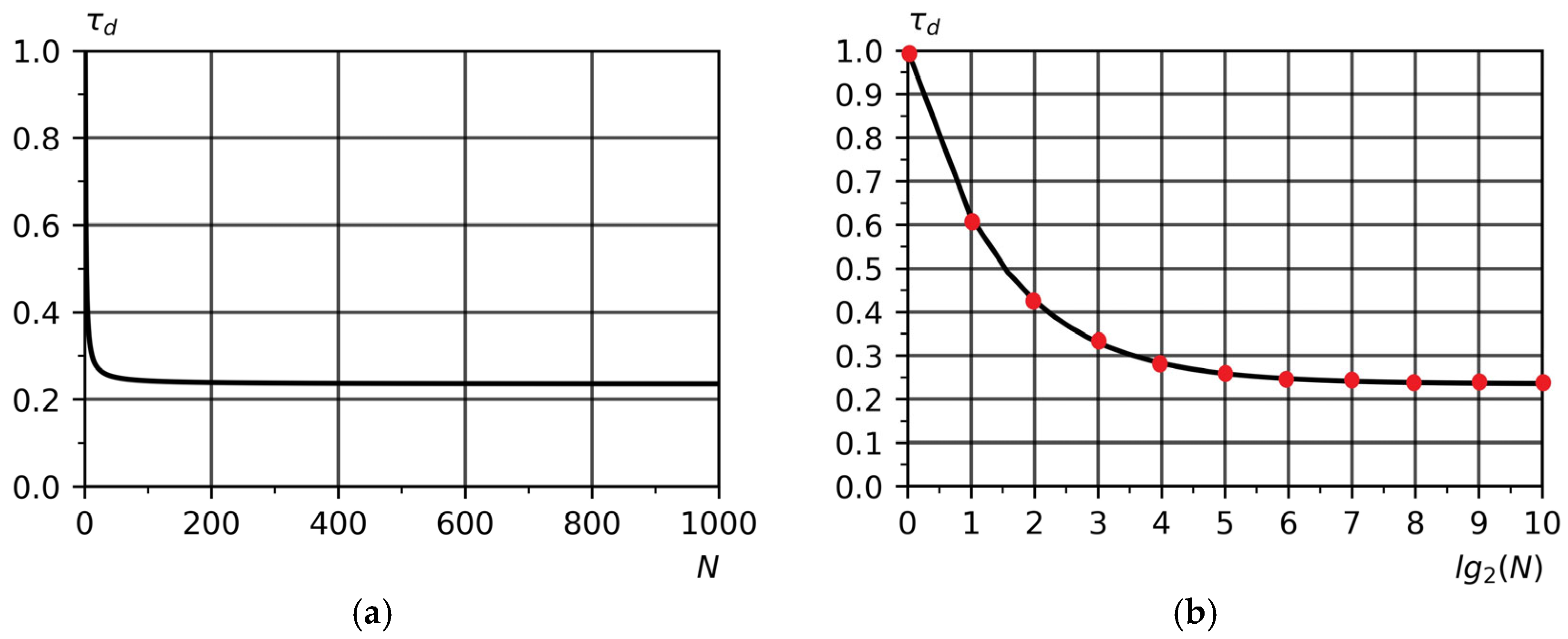

To validate the proposed stochastic model (7)–(8), a comparative analysis was conducted using the deterministic analytical model (4). The dependence of the dimensionless average processing time

on the batch size

was examined. First, the value of

was calculated analytically under deterministic conditions (4) and presented as a baseline curve (

Figure 4a). The results obtained using the stochastic simulation model according to Equations (7) and (8) were then plotted on the same graph, where the red circles show the relationship between

and

(

Figure 4b). The comparison shows that under deterministic assumptions, both models agree, while the stochastic model accounts for additional effects caused by random disturbances and bottleneck migration, thereby confirming its validity and demonstrating its analytical advantages over classical formulations.

For clarity, the calculated values of the dimensionless processing time

obtained using the stochastic model (6)–(7) are presented in

Table 5. The results show that the value of processing time

is particularly sensitive to small batch sizes, which corresponds to single-lot and small-batch production modes. As the batch size increases, processing time

gradually approaches a virtually constant value, which indicates that the influence of the initial filling of the production line becomes insignificant for medium- and large-scale production.

This trend confirms the stabilizing effect of increasing batch size on the overall efficiency of the production flow and demonstrates that after reaching a certain threshold value, further reduction in occurs very slowly with increasing value of . Consequently, the stochastic model effectively captures the transition from the unstable conditions of small-batch production to the steady-state flow patterns characteristic of mass production.

The probability that the manufacturing time of a part will exceed a given time

can be determined by the following expression:

The function

represents the risk of the production system exceeding the specified production time of a product

.

Figure 5 shows the risk functions

for small-scale serial and large-scale production of parts for an unfilled production line that does not provide for inter-operational backlogs. Each of the plots correlates with the plots in

Figure 3.

The presented risk functions

allow us to provide a sufficiently well-founded explanation for the occurrence of production risks, as well as to give an estimated calculation of the risk of failure to manufacture a batch of parts within the timeframe agreed with the customer. Risk functions also allow us to estimate the production time of a batch of parts with a given risk value. For the stochastic model of the production process in the presence of production risk factors (

Table 3), with the aggregated value of the risk function

, the processing time of the part

and the processing time

of a batch of parts are calculated in accordance with

Figure 5b,d, and are presented in

Table 6.

The value represents a threshold of acceptable production risk, indicating that the probability of exceeding the scheduled completion time should not exceed 20%. This level corresponds to standard industrial planning practices in medium- and large-batch manufacturing, where risk values below 0.2 are generally regarded as operationally acceptable. By calculating for different batch sizes, it becomes possible to determine the batch size that minimizes the expected risk under given production conditions. The resulting risk threshold can be further used as a decision support parameter in production planning systems, enabling adaptive adjustments to minimum lot sizes and customer order fulfillment deadlines to maintain an optimal production order portfolio. Integrating this parameter into planning and scheduling algorithms enables the system to dynamically balance workload and the risk of delays, thereby increasing its responsiveness to fluctuations in production demand.

Experiments conducted for a batch of 60 wooden single-leaf windows show that the processing time for

is

parts, which corresponds with a sufficient degree of accuracy to the calculated result for a batch of 64 products. As a final experiment demonstrating the practical application of the proposed batch processing time estimation method, a prediction calculation was performed for a batch of 60 single-sash wooden windows. This production order was received by a manufacturing company and served as a demonstration case for the proposed method. The assessment was conducted using

Figure 5d, which presents the cumulative distribution function of processing time for the selected risk level

. The corresponding value of the dimensionless processing time

was determined as the intersection of the horizontal line

with the model curve for the batch size

, which is closest to the actual batch size

under study. This point determines the reference value

presented in

Table 5, which serves as the predicted standardized processing time

for the analyzed production batch. The next step involved obtaining confirmation from the production department regarding the actual completion time of the manufacturing order for the batch of 60 wooden windows. Upon receiving the production report, it was determined that the total lead time for the order amounted to 41 working days. Considering the previously introduced dimensionless parameters, this observed production time was converted into its corresponding dimensionless value to enable a direct comparison with the model predictions.

Considering a single-shift production schedule with an eight-hour workday, the total production time of 41 working days was converted into minutes to ensure consistency with the model parameters.

Using the previously determined normalization factor

= 693 (

Table 2) to convert dimensional time to dimensionless time, the corresponding dimensionless processing time

for a batch of 60 wooden windows was obtained. The calculated value shows a strong correlation with the predicted dimensionless processing time

obtained using the stochastic model, confirming the model’s applicability and accuracy under real-world production conditions. This approach is currently being used at an industrial manufacturing facility to coordinate and verify planned processing times for production batches.

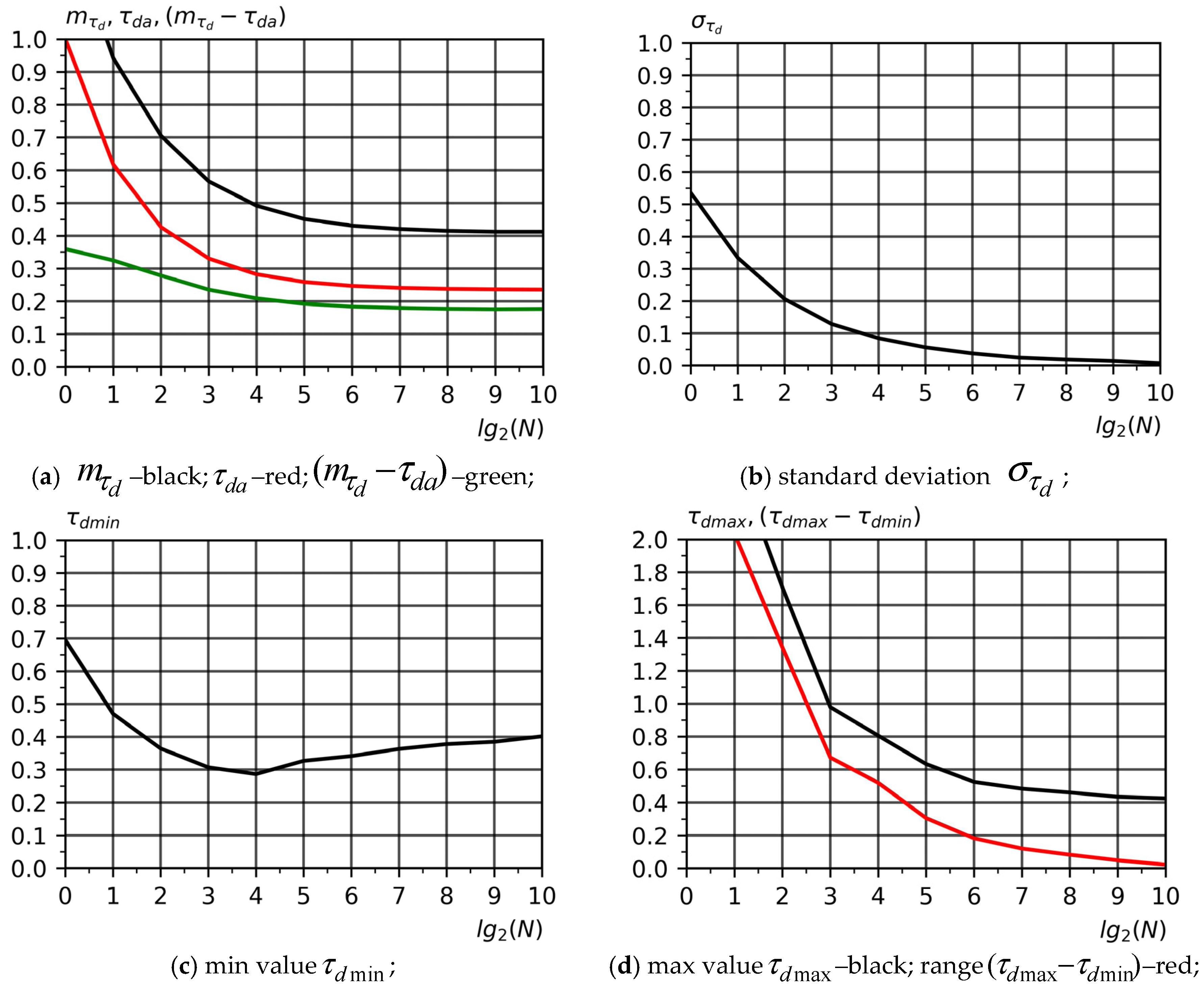

To better understand the stochastic behavior of a manufacturing system, the analysis focuses on several numerical characteristics of the part processing time

.

Figure 6 presents the statistical parameters, namely the mean

, the standard deviation

, and the variation limits

,

calculated for each lot size.

Figure 6a shows the relationship between the average processing time

obtained from the stochastic model (6)–(7) and the analytical value

calculated under deterministic conditions without production risks according to Equation (4). This comparison allows us to quantify the impact of production risks on the dynamics of average processing times and determine the extent to which random disturbances influence the stability of the process flow. The analytical model serves as a baseline, reflecting the idealized case of a perfectly deterministic production process.

To illustrate these dependencies quantitatively, the corresponding numerical values of the statistical parameters of the part processing time

, the mean

, the standard deviation

, and the lower and upper limits

,

are summarized in

Table 7. These data provide a clearer picture of how the average processing time and its variability change with lot size

, emphasizing the stabilizing effect of increasing

on production flow and confirming the asymptotic convergence of the value to a stationary value characteristic of large-scale production.

The values of

and

exhibit similar qualitative behavior with increasing batch size

. The difference between these quantities,

(

Figure 6a, green line), gradually decreases with increasing batch size in single-unit and small-scale production modes, and then asymptotically tends to a constant value in medium and large-batch production modes. This difference is determined by the average process parameters and average characteristics associated with the occurrence of production risks. A similar trend is observed for the standard deviation

, which decreases exponentially with increasing batch size, indicating a decrease in process variability. As

increases, the value of

rapidly decreases and asymptotically approaches zero, indicating stabilization of the production process with respect to production risks. In this mode, the probability density function of the part processing time

takes on a sharply peaked, becoming delta-shaped. This behavior allows for a fairly accurate estimation of the typical processing time for medium and large-scale production, where random fluctuations are minimal and the value

converges to its mean value

.

For small-scale and single-unit production, estimating the processing time can only be achieved with a certain degree of probability due to the significant influence of random production factors of risk. This effect is visually manifested as a rotation of the production risk function around an inflection point, which gradually shifts to the left as the batch size increases. The resulting compression of the distribution reflects the behavior of the functions and as the batch size increases. In the range , the minimum value decreases, which corresponds to the observed dynamic change in the average value characteristic of single-unit and small-scale production.

A further increase in the number of parts in the batch leads to an increase in the value of , which is associated with a quasi-constant value of the mathematical expectation and a decrease in the value of the standard deviation . It should be noted that both values and , which limit the value on both sides, tend to the mathematical expectation by .

The proposed model of a linear production line can be generalized to production lines with parallel–sequential technological operations. This generalization can be achieved by introducing generalized production operations containing multiple parallel and sequential operations. As the number of operations and parts in a batch increases, the load on computing resources also increases, requiring a transition from a subject–process description to a flow–process description of the production line [

15]. Furthermore, it should be noted that the model does not account for large-scale failures, which are beyond the scope of this study and should be modeled separately as rare catastrophic events.

7. Conclusions

In this research, a stochastic model of a linear production system is developed that takes into account the impact of production risks on the processing time of a batch of products. The model is based on a spatio-temporal description of the movement of parts along the process route using dimensionless parameters, which ensures the universality of the approach and its applicability to various production lines with an arbitrary number of process operations.

The introduced risk function allows for a quantitative assessment of the probability of exceeding the established production deadline and provides a practical basis for making informed decisions in production planning. It is shown that increasing the lot size helps reduce both the average product processing time and the standard deviation of processing time. For a stochastic production process, in the presence of production risks, effects arise associated with the migration of bottlenecks corresponding to the technological operation in the route with minimum productivity (i.e., the bottleneck of a linear production line).

The practical significance of the results lies in the possibility of using the proposed model to assess the reliability of production order execution, as well as in the construction of digital twins of production processes. The proposed stochastic model can be applied to other industrial contexts and production schemes, provided that the key assumptions regarding random processing times, continuous flow, and batch interactions are maintained. This adaptability makes the approach suitable for a wide range of discrete and continuous manufacturing systems, including assembly lines, conveyorized transport systems, and flexible manufacturing environments.

Future research prospects include the development of an expanded production risk assessment methodology that takes into account inter-operational buffers, adaptive rules for interactions between batches of parts, and the integration of the proposed stochastic model into digital twin systems to build an optimal control system for production line process parameters. This area of research represents a broad and practically significant field aimed at ensuring real-time risk monitoring and optimizing flow production parameters in manufacturing systems.