1. Introduction

A primary challenge in static malware analysis is the localization of malicious application programming interface (API) functionality in assembly instruction sequences [

1]. Recent work derives API-level control flow graphs and delimits regions of interest (ROIs) by inspecting the surrounding opcodes to classify the API as benign or malicious [

2]. This pipeline is demonstrably fragile under semantic-NOP insertion attacks, where an adversary inserts one or more semantically redundant NOP instruction (semantic NOPs) into ROIs, perturbing the static analysis while preserving runtime semantics. In such situations, the opcode distribution inside the ROI is shifted, which in turn displaces the feature vector used by both signature [

3] and learning-based detectors [

1], causing a measurable drop in maliciousness score. More critically, the operability and stealth of automated semantic-NOP toolkits [

4,

5,

6] make them promising to be embedded into Malware-as-a-Service ecosystems [

7], expanding the attack surface from isolated campaigns to industrial scale. Therefore, semantic-NOP removal plays an important role in malware analysis with accuracy and completeness.

Semantic NOPs are individual instructions or instruction sequences that preserve the original program semantics while altering the static representation of a function.

Table 1 lists several commonly used semantic NOPs identified in prior research. However, manual identification of semantic NOPs is impractical due to the vast volume of malware samples. Although rule-based approaches offer an automated alternative for detecting semantic NOPs, they struggle to adapt to the continuous evolution and variation of such instructions. Consequently, effective semantic NOP discovery and removal demands an automated approach capable of identifying semantic-NOP patterns, even for previously unseen instruction sequences that have never appeared in any training corpus. This requirement naturally aligns with a sequential decision problem under uncertainty, a setting in which reinforcement learning (RL) has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance. In this scenario, an RL agent treats the choice of a semantic-NOP as an action and the evasion success rate against a downstream detector as the reward. Consequently, it can continually expand its repertoire beyond known patterns and learn to remove inserted semantic NOPs.

In this work, we present MalRefiner, a fully-working reinforcement-learning system that recovers the original opcode sequence of an adversarially injected semantic-NOP malware by jointly optimizing three interacting modules: (i) a representation network, (ii) a classification network, and (iii) a policy network. First, each malware is statically disassembled into an ordered opcode stream, integer-embedded, and fed to a stacked 1D causal convolutional representation network to yield a compact, context-aware state vector. This vector simultaneously supplies the Markov state for the policy network and the input to the classification network, which returns the posterior malware likelihood used as the reward. Within this environment consisting of a representation network and a classification network, the policy-gradient refiner performs per-opcode retain/remove actions, maximizing cumulative reward so that the final, minimal opcode sequence (a) preserves original runtime semantics and (b) maximizes the confidence of any downstream static detector—without requiring retraining or architectural modification.

Experimental evaluation is conducted on two benchmark datasets, i.e., PE Malware Machine Learning (PEMML) and RawMal-TF, for semantic-NOP removal. PEMML contains 25,426 Windows PE files (2017–2018) obtained by family-stratified sampling from 201 k executables. RawMal-TF comprises 6000 samples (2023–2025) with an equal proportion of malware and benignware. We target four mainstream detectors—1D CNN, MalConv, TCN, and MALIGN—without retraining. Adversarial perturbation is generated with the Semantics-preserving Reinforcement Learning (SRL) attack, inserting semantic NOPs into at most 5% of basic blocks, yielding paired clean/adversarial samples. MalRefiner is trained on train-split and evaluated on held-out test set, attaining a recovery rate exceeding 90% on both datasets.

In summary, the contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

Semantic-NOP recovery pipeline: We present MalRefiner, an adversarial malware defense system that jointly learns to locate and remove adversarially inserted semantic NOPs.

- (2)

Causal-conv MDP backbone: We cast the task as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and design a lightweight 1D causal convolutional environment that yields compact, context-aware states and delayed detection-likelihood rewards, enabling end-to-end training with REINFORCE.

- (3)

Extensive experimental evaluation: We perform extensive experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of MalRefiner on 31k executables. Experimental results demonstrate that MalRefiner achieves a 90% recovery rate with no modification of the downstream classifier.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related adversarial-malware literature.

Section 3 formalizes the threat model and details the problem formulation, network architecture, and reward design.

Section 4 describes datasets, baselines, attack protocols, and metrics.

Section 5 presents quantitative and qualitative results and case analyses.

Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines future research directions.

2. Related Work

In this section, we first trace the evolution of semantic-preserving evasions, from PE byte injection to RL-driven NOP insertion, to illustrate the advancements of current advanced methods. Following that, we demonstrate that existing defenses primarily prioritize detection performance, leaving the malicious semantics unrestored, thereby motivating our shift toward learning to remove rather than merely resist.

2.1. Adversarial Malware Evasion Against ML Detectors

Since the migration from signature-based [

8] to learning-based detectors, adversarial research has predominantly focused on feature-space manipulation of static and dynamic models. Early work appended bytes to PE headers [

9] or injected benign API calls [

10] to shift the decision boundary of data-driven classifiers. Subsequent studies regard the problem as a constrained optimization problem: maximize misclassification probability while preserving file syntax and execution semantics [

11]. With the advent of graph-level detectors, attackers moved from raw bytes to structural features, perturbing control-flow or call graphs via node injection. Among structure-aware attacks, semantics-preserving perturbations have become the evasion method because they alter only non-functional instructions and reach a good evasion rate. Within this category, inserting semantic NOP instructions that do not alter program behavior, such as NOP, register-to-register swaps, or additions of zero, achieves good stealth.

Gibert et al. [

4] leverage a Double-DQN agent to sequentially place NOPs into the assembly code to reduce the cross-entropy loss of a data-driven classifier. Their method achieves 100% evasion on three malware families while increasing the basic-block count by merely 5%. Zhang et al. [

5] extended the idea to graph neural networks. They proposed that an RL policy jointly selects a basic block and a semantic-NOP, enabling better evading performance. Their SRL attack attains 100% evasion against both basic GCN and DGCNN detectors with less than

additional instructions, and retains 85% success even after adversarial retraining. Ling et al. [

6] present MalGuise, a black-box attack that refines semantics-preserving CFG manipulation through call-based redividing. Each call instruction splits a basic block into three sequential blocks, while semantic-NOPs are injected into the mid blocks. Their evaluation on 210 k wild samples reveals that MalGuise exceeds 95% attack-success rate while preserving original API-level semantics in over 91% of cases.

2.2. Adversarial Defenses on Evading Malware

With the rapid evolution of adversarial attacks against malware samples, defending machine learning detectors has recently become a priority. Adversarial training is now a standard robustness strategy: Lucas et al. [

12] perform large-scale adversarial training on raw-byte models and demonstrate that lightweight, gradient-guided augmentations transfer robustness to stronger malicious variants while leaving the malicious byte sequence intact.

In recent years, researchers have proposed robust architectures and dedicated threat indicators. Li et al. [

13] present RAMDA, a robust Android malware detection framework that couples a feature-disentangled VAE (FD-VAE) with an MLP classifier. By learning a compact latent space that cleanly separates benign, malicious, and adversarial samples, RAMDA attains a good defense success rate of over 90% against seven diverse adversarial attacks without requiring adversarial examples at training time, thereby generalizing well to unseen attacks. Rashid et al. [

14] introduce MalProtect, a stateful defense to detect adversarial query attacks against ML-based malware detectors. By analyzing query sequences with multiple anomaly-based indicators, including query similarity, feature overlap, and auto-encoder reconstruction loss, MalProtect reduces evasion rates by

on both Android and Windows datasets, outperforming prior stateful defenses. Although these approaches preserve detection accuracy, they do not attempt to recover the original malware semantics, which is an essential prerequisite for downstream malware analysis.

2.3. Reinforcement Learning for Malware Evasion and Defense

With the rapid evolution of adversarial attacks targeting machine learning-based malware detectors, reinforcement learning has emerged as a powerful framework for modeling sequential decision-making in both malware evasion and adversarial defense. Existing RL-based approaches predominantly treat the malware sample as an indivisible unit, abstracting the adversarial generation or defense process as a high-level policy optimization problem. Zhong et al. [

15] exemplify this paradigm by treating the entire modified executable as the RL state. It employs dynamic programming and temporal difference learning to explore sequences of perturbations and uses VirusTotal as a black-box detector to provide reward signals. Similarly, Ravi et al. [

16] adopt a holistic view by embedding the binary as an RGB image and using the full image as the RL state. A ResNet-18 surrogate model provides reward feedback, guiding the agent to insert semantic NOPs into the executable region of binary files. On the defensive side, Liu et al. [

17] leverage inverse reinforcement learning to model malware behavior as a sequence of system-level interactions. It constructs a dynamic heterogeneous graph to represent malware–system relationships and infers attack intent from observed behavior trajectories.

These methods concentrate on the whole malware sample and disregard the internal opcode sequence, which encodes the core logic and functionality of the program. This coarse-grained abstraction hinders their ability to perform fine-grained defenses, particularly when locating subtle instruction-level changes that can yield significant evasion gains.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior work has concentrated on the automated selective removal of adversarial semantic NOPs. We close this gap with a policy-gradient agent that learns to remove semantic NOPs, directly maximizing the confidence of the downstream ML detector.

3. Methodology

In this section, we first give the threat model and formulate the problem. Then, following the mathematical symbols in problem formulation, the environment and agent are introduced. Finally, rewards and the update strategy of the model parameters are present.

3.1. Defense Model

Following previous works [

18,

19], the defense model in this paper focuses on three key components: defender goals, knowledge, and capabilities.

Defender goals: The defender aims to remove semantic NOPs from adversarially altered malware samples. These instructions do not alter program behavior but can cause ML-based detectors to misclassify malicious binaries. This work focuses on removing such NOPs to restore the malware to its original, pre-obfuscation state.

Defender knowledge: We assume the defender operates the target ML-based malware detector and receives a batch of suspicious obfuscated samples. The defender observes the obfuscated samples and its true labels are malware, but has no knowledge of how or where semantic NOPs were inserted. Adversaries release the crafted sample but keep the original sample and their generation pipeline confidential.

Defender capabilities: The defender is assumed to possess two core capabilities: (1) query access to the target ML-based malware detector, enabling the acquisition of a predicted label for any submitted sample; (2) the ability to reverse-engineer a binary executable and extract its ordered opcode sequence, which constitutes the input to our method. Since the removal of adversarially injected semantic NOPs is a non-trivial task, these prerequisites mirror the skill set routinely expected of operational malware analysts.

3.2. Problem Formulation

Let

be the set of binary executables and

the

L-dimensional feature space produced by static or dynamic analysis. Each feature vector

is extracted from a original malware sample

through a deterministic feature map

, i.e.,

. Labels are drawn from

, where 1 indicates malware and 0 indicates benignware. Then, a data-driven malware classifier is

aiming to correctly classify all samples.

An adversarial obfuscation attacker aims to produce an obfuscated malware sample

that evades the classifier

F, i.e.,

. Conversely, the semantic-NOP removal task in this paper seeks a reverse operation

R that recovers the original malware representation:

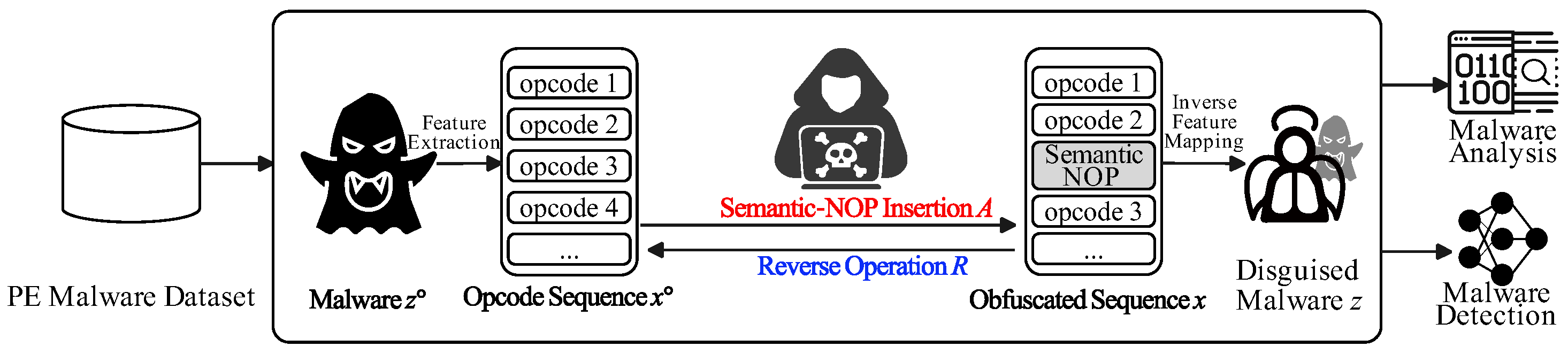

. The overall attack-and-defense workflow is presented in

Figure 1. Thus, the core challenge lies in learning a removal function

R that approximates the inverse of

A without access to

.

Since individual semantic NOPs may exhibit contextual dependencies, their NOP-like behavior emerges only when they form an inter-instruction sequence. Therefore, we cast the semantic-NOP removal task as a Markov Decision Process:

, where

denotes the state space,

is the action space,

denotes the transition kernel parameterized by a policy network, and

denotes the rewards of

. As illustrated in

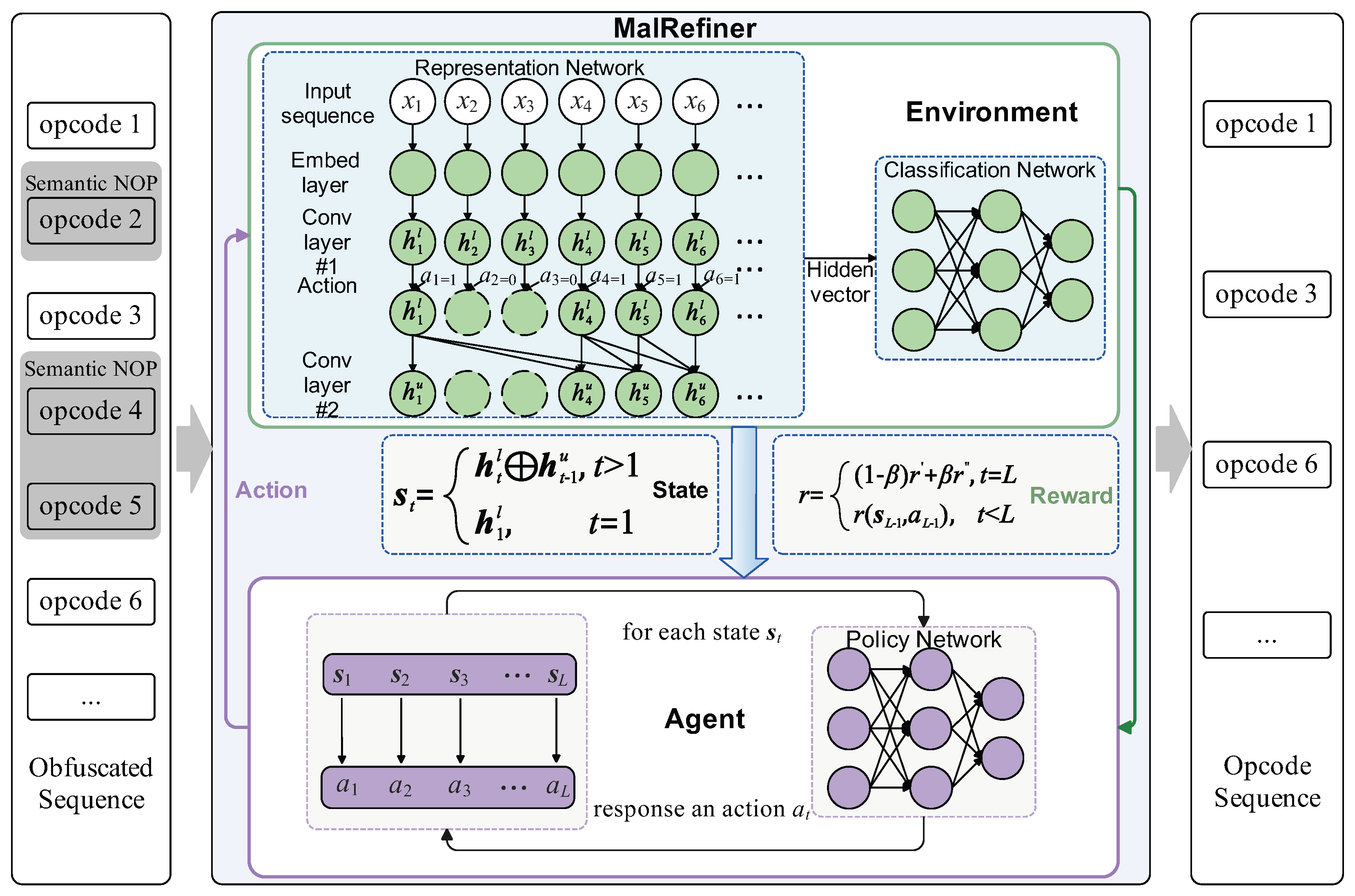

Figure 2, MalRefiner couples a convolutional environment with a policy-gradient agent. The environment embeds the opcode sequence in a causal 1D latent space via a representation network, and returns a delayed malware-likelihood reward via a classification network. The agent receives the hidden vector from the representation network and produces a retain/remove decision for each opcode to maximize detector confidence while preserving runtime semantics. Both modules are co-trained with REINFORCE to yield the recovered opcode sequence.

3.3. Environment

The environment comprises a representation network and a classification network. Since their parameters are updated jointly, the two networks form a single entity, termed the environment network. The representation network produces the hidden vector that serves as the state, and the classification network outputs the reward.

3.3.1. Representation Network

To balance representational capacity with training efficiency, we stack two lightweight 1D causal convolutional blocks instead of recurrent or self-attention layers. Causal convolution ensures that the state at position t is computed solely from opcodes , satisfying the sequential decision constraint of the MDP while retaining parallelizability. Dilated kernels capture local instruction patterns without the quadratic complexity of self-attention or the sequential bottleneck of recurrent networks.

In the first convolutional layer, the kernel size is set to 1. This layer serves two purposes: (1) reducing the dimensionality of the input vectors for efficient representation; (2) establishing alignment between the input layer and the subsequent convolutional layer, which facilitates vector concatenation in the state representation. In the second convolutional layer, the kernel size is denoted as k, which is set to 3 in this paper. This choice is motivated by the observation that a semantic NOP typically consists of at most 3 NOP instructions. Therefore, neurons in this layer are computed based on 3 adjacent neurons from the previous layer, enabling the model to capture local instruction-level patterns.

In sequence modelling, the fundamental task is to predict an output sequence under an input sequence that is ordered chronologically. In such tasks, the goal is to predict the output at time step t using only the preceding input subsequence . This constraint is known as the causal constraint, which ensures that no future information is used in the prediction. In the context of malicious sequence analysis, adhering to this constraint is essential to maintain the integrity of the temporal modeling process.

3.3.2. State

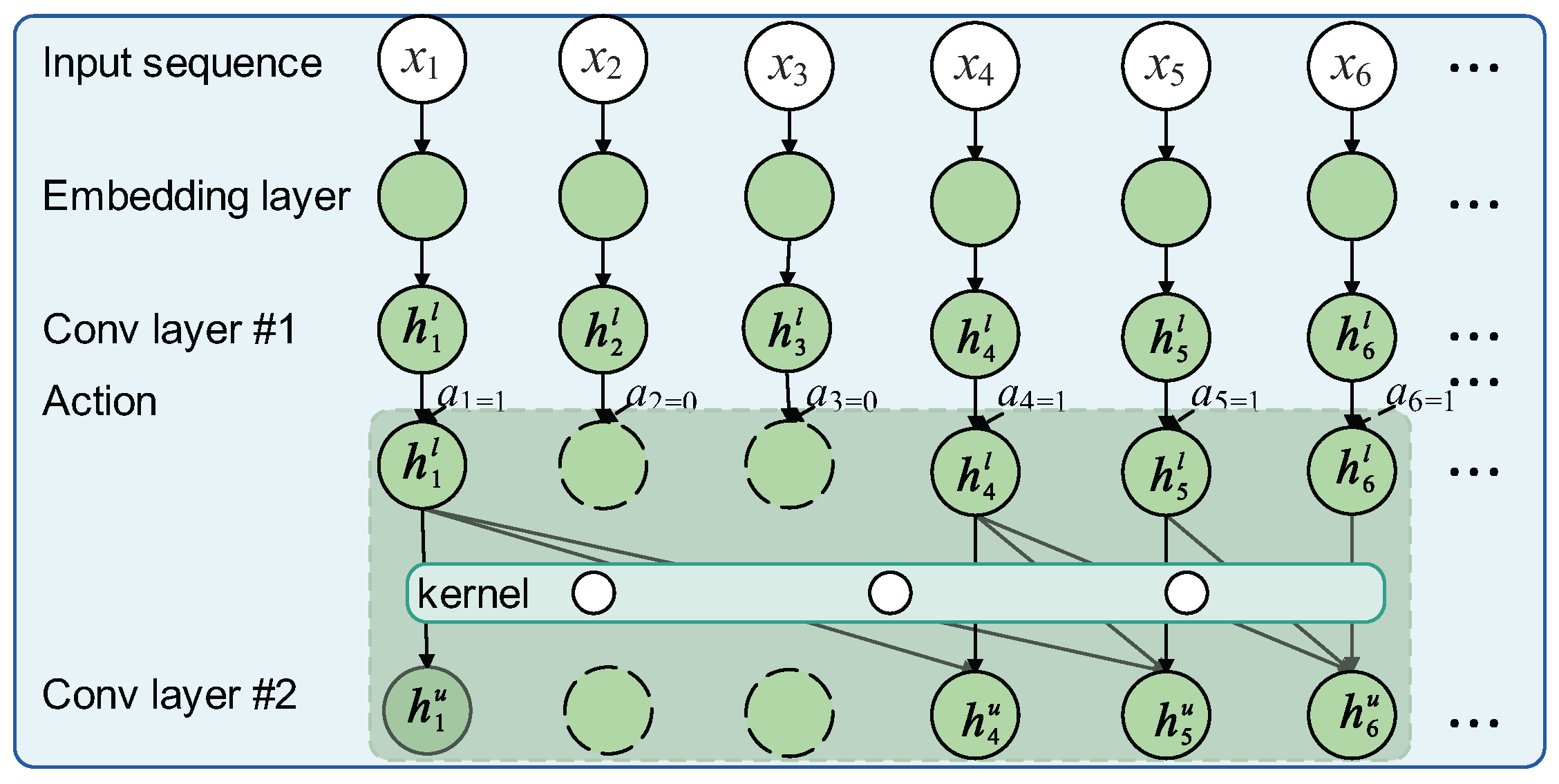

To elucidate the state representation,

Figure 3 presents an instance of the calculation of state under several conditions with different retain/remove mask.

Situation 1: If

and the preceding

actions are all 1, the convolutional kernel slides across the hidden representation from the lower convolution layer, and the hidden representation at upper layer

can be computed

where

denotes the representation from the first convolutional layer,

denotes the convolution kernel, ∗ denotes the convolutional operator, and

k denotes the kernel size in the upper convolutional layer, which is 3 in this setting. For instance,

in

Figure 3 is

Situation 2: If

, the opcode is removed, and the corresponding representation

and

are both undefined. Following [

20], we copy the previous hidden vector. As in

Figure 3,

is

Situation 3: If

, but some earlier actions were 0, the receptive field is shifted to the nearest valid positions. As in

Figure 3,

is

Collectively, the update of

is is summarised by Equation (

6).

In this work, considering semantic NOPs span at most three consecutive opcodes, two consecutive hidden representations suffice to capture the semantic NOPs. Therefore, the RL state is designed as

where ⊕ denotes concate operator and

resorts to

because no preceding context exists.

3.3.3. Classification Network

The classification network is a lightweight multi-layer perceptron that maps the compact, causal representation produced by the representation network to a malware posterior. It consists of two fully connected layers, each followed by a ReLU non-linearity and a dropout layer. The first FC layer projects the 128-dimensional hidden vector to 64 units, and the second reduces the dimension to 2, yielding the logits for benign and malware. Finally, a softmax operator converts these logits into a probabilistic output.

3.4. Agent

From above, the representation and classification networks constitute the environment. The agent interacts with this environment by drawing actions from a policy network that decides, at each position t, whether to retain or remove the current opcode.

Action Space and Policy Network

The action set is binary:

, with 0 meaning the remove operation and 1 meaning the retain operation. At time step

t, the agent feeds the state vector

to a two-layer policy network:

where

denotes the trainable parameters,

is the sigmoid function, and

denotes the ReLU function.

3.5. Reward

The reward is composed of two complementary terms: (i) a log-likelihood score that quantifies the increase in detector confidence after refinement and (ii) a bonus that encourages the removal of redundant opcodes. The first term ensures that the refined sequence recovers the malicious signal recognized by the downstream classifier, while the second term discourages the agent from retaining instructions whose only purpose is to increase the binary size without altering program behavior, thereby guiding the policy toward a concise yet semantically equivalent opcode sequence.

The first reward component

r′, derived from the classification network, is defined as the log-likelihood gain achieved after refinement:

where

represents the predicted probability from the environment network,

is the ground-truth label of the original input sequence

, and

x′ is the refined sequence. This reward

r′ encourages the refinement process to adjust the input, reclassifying samples originally regarded as malware.

The second reward

r′′, to encourage the removal of semantic NOPs, is designed as

where

is the number of removed opcodes, and

L denotes the original sequence length. The reward is constrained to

to match the scale of the log-likelihood reward.

Since every action contributes to the final outcome, a single delayed reward is broadcast along the trajectory

with

where

is a weight factor to balance the two reward terms.

Finally, the expected return over a sampled trajectory

is then

where

is the policy probability of choosing action

in state

.

3.6. Model Training

To optimize the parameters in

, we employ the REINFORCE algorithm [

21] in Equation (

12). Assuming

N trajectories are sampled via the Monte Carlo method, the gradient of the expected reward with respect to

is given by

The training involves a coupled update scheme between the RL refiner and the environment network: the refiner’s updates depend on the environment network. In contrast, the environment network is trained using sequences revised by the refiner. To facilitate effective cooperation between the two components, we adopt a pre-training strategy. First, the environment network is trained independently, without involving the refiner. Then, with the environment network fixed, the RL refiner is trained to refine input sequences. Finally, both components are jointly fine-tuned. During joint training, the parameters of both the environment network and the policy network are updated using a stable strategy following [

22], which combines old and new parameter values as follows:

where

denotes the newly computed parameters in the current iteration, and

represents the old parameters.

In the RL training process, delayed rewards guide the direction and magnitude of parameter updates. These rewards are only available after the entire sequence has been sampled by the policy network. Once obtained, the rewards are used to update the policy network parameters. Since the same policy network—with identical structure and parameters—generates actions for all inputs in a sequence, the action selection process benefits from the parallelism of the convolutional architecture, thereby accelerating training. The overall training procedure is outlined in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Training process |

- 1:

Require: - 2:

Training data ; - 3:

Representation network and classification network with parameters ; - 4:

The Policy Network with parameters ; - 5:

Number of epochs e, batches per epoch b, number of input sequences per batch d. - 6:

Ensure: - 7:

Optimized parameters and . - 8:

Initialize the network parameters and ; - 9:

Pre-train the representation network and classification network, assuming all the inputs are reserved; - 10:

Pre-train the RL structure by Equation ( 13); - 11:

Train these two structures jointly: - 12:

for each epoch e in do - 13:

for each batch b in do - 14:

for each sequence d in do - 15:

Sample a trajectory for the sequence with ; - 16:

Compute the log-likelihood with ; - 17:

Compute the reward of the trajectory using Equation ( 12); - 18:

for in the trajectory do - 19:

Spread the reward to all the pairs of state and the corresponding action and construct ; - 20:

end for - 21:

Compute the gradients according to Equation ( 13); - 22:

end for - 23:

Update parameters and by Equation ( 14). - 24:

end for - 25:

end for

|

4. Evaluation Settings

In this section, we detail the datasets, experimental environment, parameter settings, evaluation metrics, target models, and attack method used throughout the experiments.

4.1. Datasets and Experimental Setup

All experiments were conducted in TensorFlow 2.8.0 on a Windows Server with dual Intel® Xeon® E5-2620 v4 CPUs (16 physical cores, 32 threads), 128 GB DDR4 memory, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090D GPU with 24 GB memory.

4.1.1. Datasets

Contemporary data-driven malware research faces two principal constraints. First, raw executables are rarely distributed because of legal and ethical concerns, and hence extracted feature vectors are more common, which impedes studies that require direct assembly manipulation and semantic-NOP insertion. Second, most reference collections, including the widely used Microsoft BIG 2015 dataset [

23], are more than a decade old. Finally, we chose two open-access datasets that (i) supply the actual binaries and (ii) span distinct time windows, ensuring the evaluation covers both legacy and modern malware.

PEMML (

https://practicalsecurityanalytics.com/pe-malware-machine-learning-dataset/, accessed on 28 May 2025): The PEMML (PE Malware Machine Learning) dataset is a publicly accessible collection of Windows Portable Executable (PE) files, originally compiled to support machine learning-based malware detection research. It comprises 201,549 executables (114,737 malicious, 86,812 benign) with raw binaries supplied for both classes. In this work, we downsample the dataset by selecting samples from the top-10 most representative malware families and an equal number of benign samples to ensure a balanced and tractable evaluation setup.

RawMal-TF [

24]: The RawMal-TF dataset provides more than 250,000 malware samples from 17 families. Since it contains only malicious executables, we supplement it with 3000 benign PE files from PortableApps (

https://portableapps.com/, accessed on 28 May 2025). We then randomly draw 3000 malware instances from the original pool, yielding a balanced dataset for experimentation.

Since few public collections offer both benign and malicious binaries, we limit our evaluation to the two datasets described above. Each dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets with a ratio of 0.64:0.16:0.20, respectively. In the following experimental evaluation, this splitting procedure is repeated five times with independent random splits to ensure the reliability and robustness of the experimental results, mitigating the influence of random variation, while preserving the overall class distribution in each split.

Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of the resulting experimental datasets, including sample counts, family distributions, and temporal coverage.

4.1.2. Implementation

The maximal length of the input sequences is set to 3000. For the environment network, the learning rate is set to , the embedding dimension is 300, and the number of filters and neurons in convolutional layers and fully connected layers are both 128. For the RL refiner, the learning rate is , the dimension of the hidden layer is 20, and the weight factor is set to for the PEMML and for the RawMal-TF dataset. In addition, is set to to control the update speed of the network parameters. In addition, some tricks are utilized in this work. Learning rate schedule is an extra strategy in the training phase. The learning rates reduce to of their original values every 1000 steps on both datasets.

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the model’s performance, we adopt a suite of standard classification metrics, i.e., Precision, Recall, F1-score (F1), Accuracy (ACC), False-Positive Rate (FPR), and False-Negative Rate (FNR). Furthermore, we gauge adversarial effectiveness and defensive robustness by reporting the Attack Success Rate (ASR) and the Recovered Rate (RR), respectively. Definitions are summarized in

Table 3.

4.2. Target Models

Recently, a variety of data-driven malware classification methods have been proposed and evaluated on publicly available datasets. To benchmark the performance of our proposed approach, we compare it with several representative methods, including the following:

1D CNN: A lightweight convolutional baseline model that replaces recurrent layers with one-dimensional convolutions to reduce memory usage and training time. The architecture follows the design of the environment network described in

Section 3, comprising 128 filters with kernel size 3, ReLU activation, global max-pooling, and a fully connected layer with 128 neurons.

MalConv [

25]: An end-to-end byte-level convolutional neural network that processes the entire PE file (up to 2 MB) via an embedding layer, followed by a gated convolutional block and a single dense output layer. We adopt the original architectural settings, including an embedding dimension of 8, a stride of 500, and a gating width of 128.

TCN [

26]: A temporal convolutional network that utilizes stacks of dilated causal convolutions with residual connections to capture long-range sequential dependencies without suffering from gradient degradation. In our implementation, we retain the original channel width of 128 and follow the dilation schedule of [1, 2, 4, 8, 16], as suggested in the original work.

MALIGN [

27]: A biologically-inspired sequence alignment-based method for malware family classification. MAlign converts raw byte sequences into nucleotide representations and applies multiple sequence alignment to identify conserved code regions across malware families. These conserved regions are then used to compute alignment scores, which serve as features for a logistic regression classifier. Unlike traditional deep learning models, MAlign is designed to be interpretable and robust against adversarial perturbations.

For all baseline models, we apply consistent preprocessing steps, including data normalization and sequence truncation or padding. Additionally, we use the same train/validation/test split and early-stopping criteria to ensure a fair comparison.

4.3. Attack Methods

Adversarial semantic-NOP insertion has attracted considerable research interest in recent years. Representative approaches include SRL [

5], ADVeRL-ELF [

16], and the method proposed by Gibert et al. [

4]. Gibert et al. restrict themselves to inserting literal NOP instructions, which can be trivially detected by scanning for standard NOP opcodes. ADVeRL-ELF, although more sophisticated, is tightly coupled to the ELF format and targets exclusively Linux environments. Consequently, we select SRL as the attack method for this study because it is format-agnostic, preserves functional semantics, and resists static signature detection.

Table 4 summarizes the performance of these malware detection models on the clean test sets drawn from PEMML and RawMal-TF datasets. From the detection performance on these two datasets, RawMal-TF is clearly the easier dataset because of the better generalization ability of these machine learning models on it. From the perspective of the machine learning models, MALIGN consistently delivers the highest accuracy and the lowest false-positive rate. On PEMML, it surpasses the widely used MalConv baseline by 6.35% in accuracy and 4.41% in FPR. On RawMal-TF, all four models exceed 98% accuracy.

Towards the target detection system, we further measure the robustness to the SRL attack on the test samples. Following [

5], we allow the adversary to insert semantic-NOP instructions into at most 5% of the basic blocks.

Table 5 reports the post-attack performance of the four models. On the PEMML set, the detection accuracy of MalConv drops from 80.47% to 46.16%, while MALIGN falls from 91.45% to 59.19%. On the RawMal-TF dataset, the attack attains a 100% evasion rate as reported in [

5], saying every correctly classified malware sample can be perturbed into a form that all four detectors misclassify.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the recovered performance of the proposed MalRefiner and conducts a detailed analysis of the recovered input.

5.1. Performance Evaluation of the MalRefiner on Four Target Models

Table 6 and

Table 7 report the quantitative recovery performance of MalRefiner on the PEMML and RawMal-TF datasets, respectively. All metric values represent the averages over five independent experimental runs.

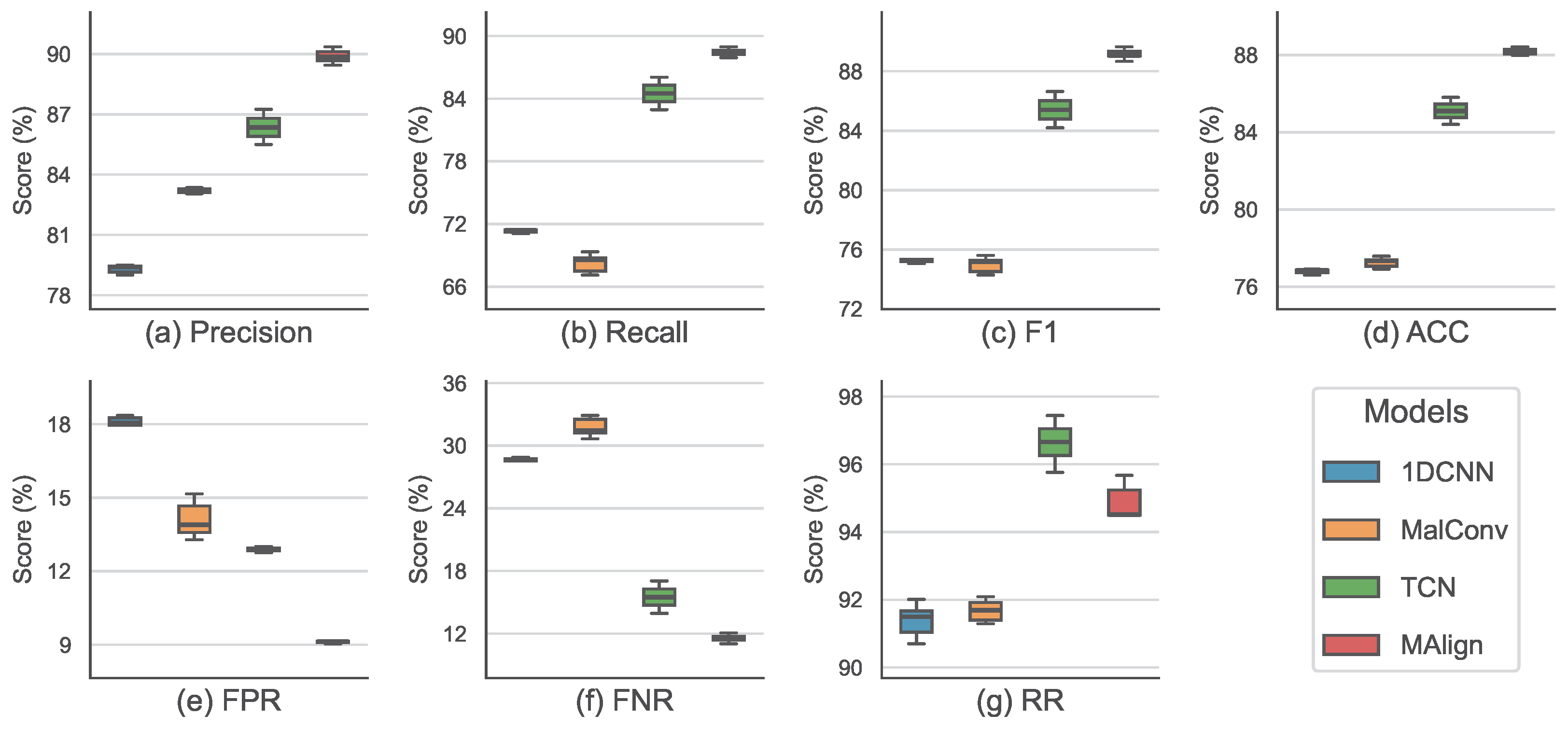

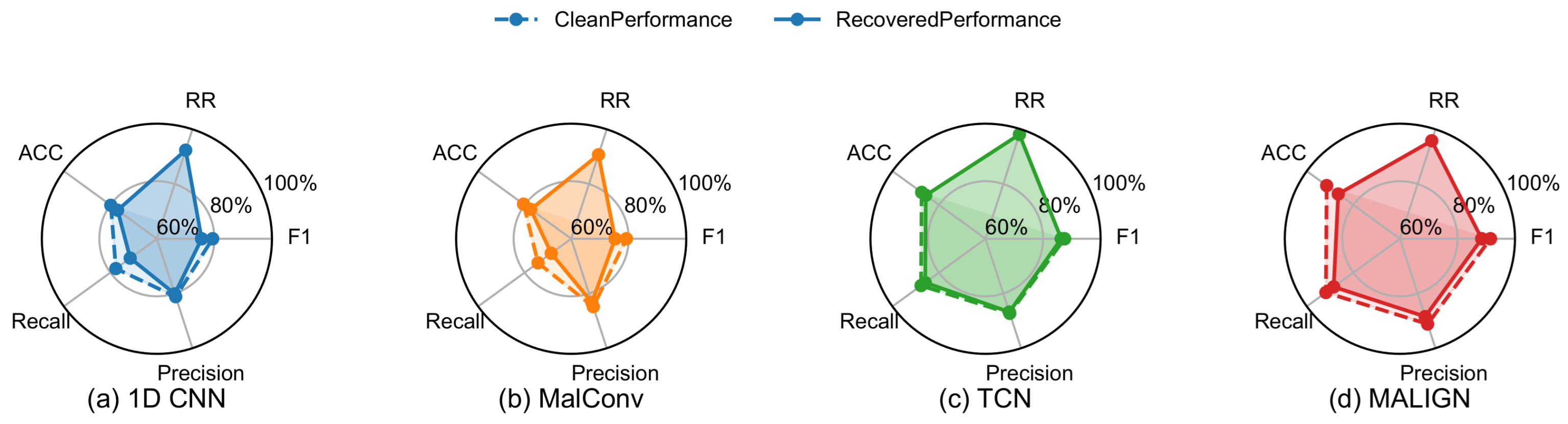

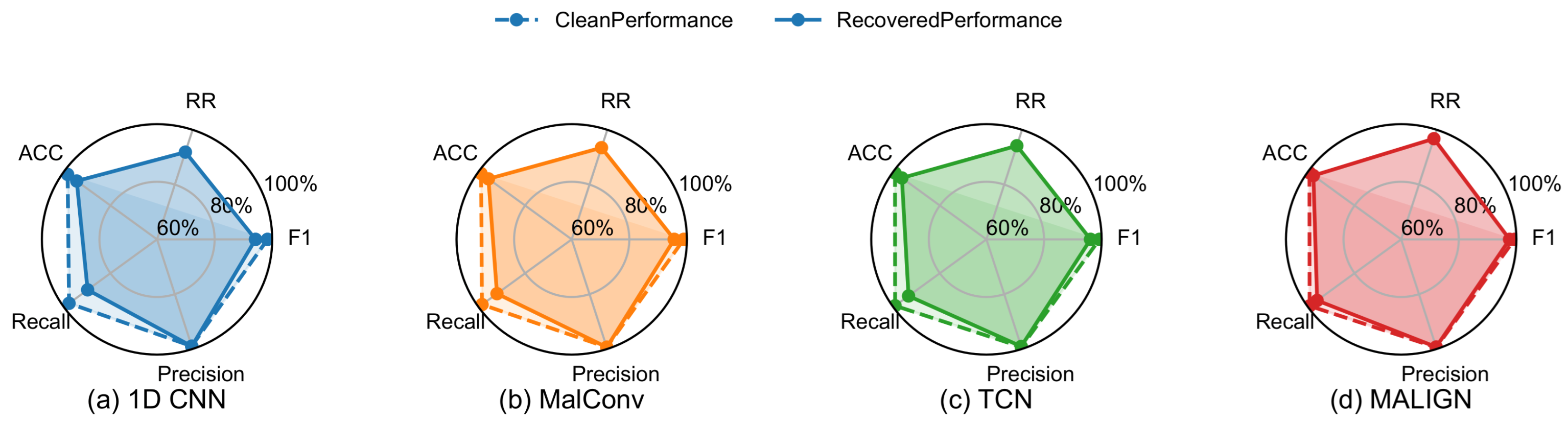

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 present the corresponding boxplots of these five runs, highlighting the dispersion and stability of performance metrics across different trials. In contrast,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 compare the recovered performance with the clean-set baseline, illustrating the extent to which MalRefiner can restore the detection capability.

The performance of the MalRefiner is evaluated on four target models because its performance is indirectly measured through the recovered detection results, rather than by direct task-specific indicators. From

Table 6, refined inputs reach an accuracy of 77.25% on MalConv and 88.17% on MALIGN, corresponding to drops of 3.22% and 3.28% relative to clean-set performance, with FPR increases of 0.81% and 0.23%, respectively. TCN delivers the highest RR with 96.63%, and achieves a relatively balanced Precision of 86.36%, Recall of 84.50%, and F1 of 85.41%.

Figure 4 shows consistently narrow interquartile ranges and minimal outliers, suggesting that recovery is stable across different random splits. The clean-vs.-recovered comparison in

Figure 6 reveals that Precision drops less sharply than Recall, implying that most unrecovered detection errors occur in originally well-classified malicious samples. Overall, all recovery performances, mainly estimated by RR, reach above 90%.

Table 7 shows MalConv restored to 94.14% accuracy and MALIGN to 97.73%, with small FPR increases of 0.04% and 0.17%, separately. In addition, all four models exceed 92% RR, and TCN achieves 96.27% accuracy with an F1 of 96.20%.

Figure 5 exhibits extremely tight metric distributions and very few outliers, indicating recovery consistency even for different data splits. Overall, RawMal-TF yields higher absolute accuracy and lower variance compared to PEMML. In

Figure 7, all metrics show mild declines relative to clean-set baselines, and RR ranges from 92% to 96%, revealing strong restoration capability for this dataset.

The comparative analysis highlights that while PEMML poses greater challenges for byte-based models such as MalConv, due to longer and more diverse code sequences, the recovery process remains stable with RR above 91% in all cases. RawMal-TF appears to show slightly better reproducibility and absolute performance, which may be attributed to dataset structure simplicity. The boxplot results across both datasets show low dispersion, suggesting that MalRefiner’s recovery effectiveness is not sensitive to training–validation splits and can generalize across malware datasets.

5.2. Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis of Removed Semantic Nops

To better understand how MalRefiner restores model confidence, we first quantify which semantic NOPs are actually eliminated, and then inspect concrete opcode sequences to verify the semantic-preserving nature of the removals.

Quantitative statistics:

Table 8 summarizes the five most frequently removed patterns on the PEMML test set. On average, SRL inserts 64 self-exchanging

xchg instructions per sample, and MalRefiner removes 53 of them, yielding an 85.94% RP. The

push edi; pop edi pair is deleted in about 66.66% of its occurrences, whereas

nop opcodes are removed completely with an RP of 100%. Double

bswap and canceled

add-sub pairs exhibit RPs of 75% and 62.5%, respectively. These results indicate that the policy-gradient agent consistently targets instructions whose sole effect is to alter the static byte sequence while leaving runtime semantics intact.

Qualitative inspection:

Table 9 presents concrete opcode slices extracted from the same executable before and after refinement. In the first fragment, the adversary adds an extra

push-pop pair and a redundant

xchg ebx, ebx between consecutive

call instructions. After refinement, only one

push-pop token remains, and the

xchg is entirely eliminated, shortening the sub-sequence from 13 to 11 opcodes without disturbing the call-site logic. The second slice contains a duplicated

xor and an inserted

bswap eax; bswap eax inside an arithmetic block. MalRefiner merges the duplicate

xor and strips both

bswap instructions, restoring the original four-instruction pattern.

From the above two experiments, the statistics and the case studies demonstrate that MalRefiner successfully learns to remove the same categories of semantic NOPs that adversaries inject, thereby recovering a representation that is both more concise and more amenable to correct classification and analysis.

From

Table 9, we present concrete proof-of-concept cases demonstrating the recovery of input sequences after semantic-NOP removal. To further clarify the performance recovery of the detectors shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7, we provide an explanation from the perspective of posterior scores, highlighting how MalRefiner mitigates elevated false negative rates (FNRs). Specifically, the two malicious samples reported in

Table 9 were subjected to an SRL attack and misclassified as benign by the baseline detector due to heavy insertion of semantic NOPs. As indicated in

Table 10, the posterior scores for the malicious label dropped from 0.87 and 0.94 to 0.36 and 0.28, respectively, both falling below the detection threshold. After refinement with MalRefiner, removal of the inserted NOPs restored the posterior scores to 0.78 and 0.80, respectively, thereby enabling correct classification. It is worth noting that the semantic-NOP attack is specifically designed to conceal malicious content, and benign software is rarely subjected to such an obfuscation technique. Consequently, MalRefiner has minimal impact on benign samples in this setting, and both the false positive rate (FPR) under SRL attack and the FPR after refinement remain essentially unchanged.

5.3. Computation Time and Stability Evaluation of MalRefiner Training

To assess the practical viability of MalRefiner in real-world scenarios, with particular emphasis on computational efficiency and training stability, we provide detailed analyses of the average rewards and computation time of MalRefiner in this part.

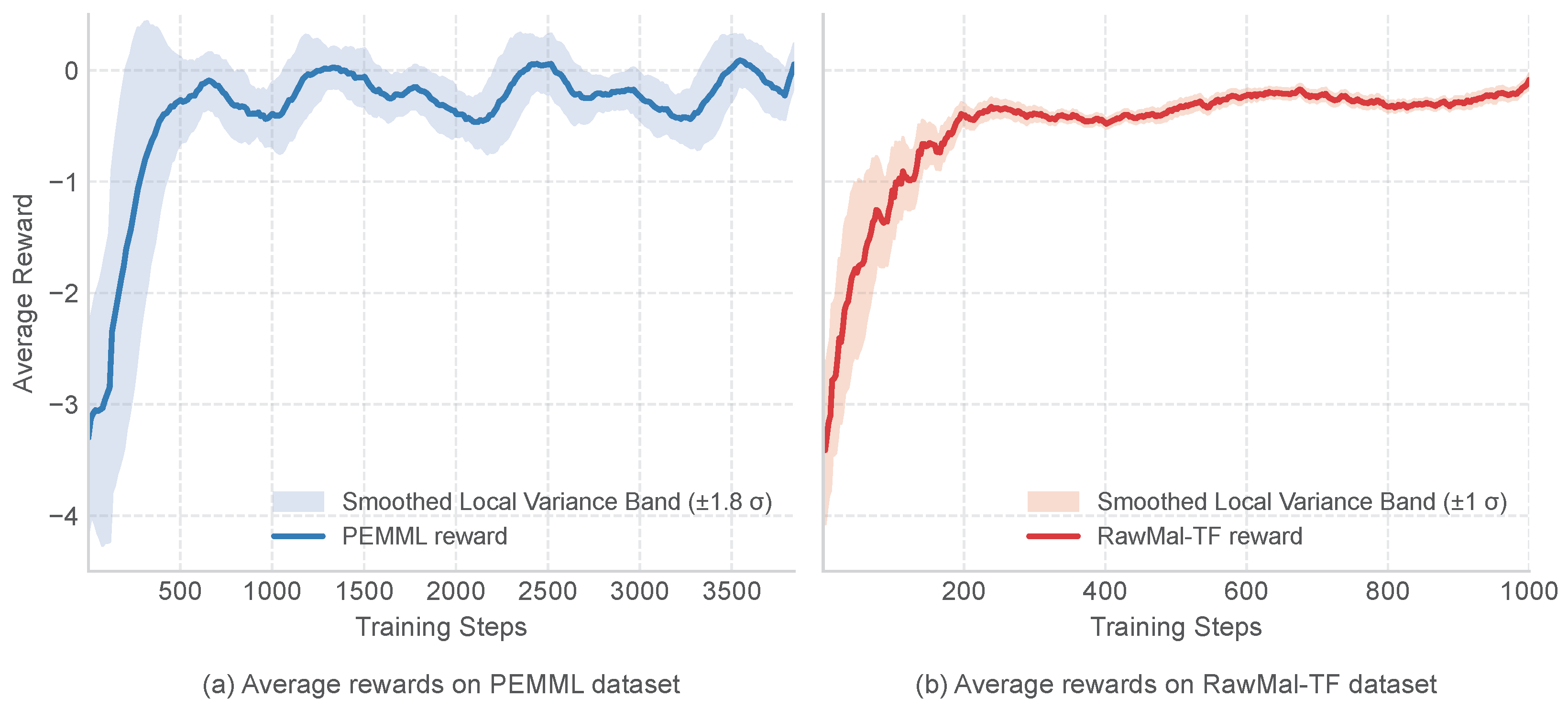

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the average reward curves of MalRefiner on both datasets exhibit a clear convergence trend, though the rate of convergence and the degree of fluctuation differ noticeably. For the PEMML dataset in

Figure 8a, the average reward enters a stable phase after approximately 2500 training steps, with a relatively narrow local variance band, indicating that the policy updates have become stable in the later training stages. Nevertheless, the early-stage rewards display certain negative fluctuations, which can be attributed to the exploratory nature of the policy network before it establishes a consistent decision-making pattern. In contrast, on the RawMal-TF dataset in

Figure 8b, the reward curve shows a marked improvement after approximately 600 steps and reaches stability after around 1000 steps. Moreover, the overall curve suggests faster convergence and reduced volatility. This observation aligns with the relatively simple distribution of RawMal-TF samples, which facilitates stronger generalization capability for the underlying representation and policy networks.

Table 11 reports the total computation time of MalRefiner and four downstream classifiers across both datasets. The results demonstrate that the training time of MalRefiner takes the most time of the whole diagram. On the PEMML dataset, training MalRefiner requires approximately 235,296 s, which is nearly two orders of magnitude greater than the slowest baseline MALIGN. For the RawMal-TF dataset, although the overall training time is reduced to 105,043 s, it remains significantly higher than that of lightweight classifiers such as TCN. This demonstrates the substantial computational overhead inherent to the reinforcement learning framework. Encouragingly, the training process needs to be performed only once, after which the model can be deployed and continuously utilized over an extended period.

5.4. Threats to Validity and Limitations

In this work, we focus on the removal of inserted semantic NOPs, while the executability of the resulting samples is not validated. This issue lies beyond the primary scope of the current study. However, the inverse feature mapping operations can be implemented using the same techniques employed in existing semantic NOP insertion methods.

Moreover, the generalization capability of the proposed method across various semantic NOP insertion attacks has not been thoroughly evaluated. In addition to automatic semantic NOP insertion techniques, experiments involving manual obfuscation methods, which typically offer higher stealthiness, could better demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach. Nevertheless, constructing a reliable manually obfuscated dataset is time-consuming and is left as future work.

From the perspective of the model itself, the limitations of the proposed method are summarized as follows:

High Training Overhead: One of the most significant drawbacks is the extensive training time required. The reward evaluation of the reinforcement learning (RL) model is computationally intensive. Furthermore, the framework involves two networks—namely, the environment network and the policy network—that need to be jointly optimized. Although RL offers a promising paradigm for sequential decision-making and is more resource-efficient than manual analysis, it still incurs substantial time costs during training and parameter tuning.

Discrete Semantic NOPs Not Addressed: The proposed method does not address the case of discrete semantic NOPs. As discussed in this paper, current semantic NOP insertion techniques tend to place NOPs in consecutive positions to avoid execution errors. More sophisticated and stealthy strategies may emerge in the future, such as distributing semantic NOP operations across non-adjacent instructions.