6.1. Case Studies

Simulation studies were designed to represent the most critical operating scenarios encountered in IVC-IMs and were conducted under six conditions. The initial two scenarios examined the system’s dynamic response to changes of varying magnitudes in the reference speed. High-amplitude speed transients, in particular, generated varying dynamic demands, while low-speed changes were used to evaluate the controllers’ sensitivity and small-signal behavior. The third and fourth scenarios investigated the controllers’ recovery performance and stability characteristics under varying load disturbances applied to the system. These scenarios are critical for measuring the motor drives’ capability for disturbance rejection. The fifth and sixth scenarios focused on parameter uncertainties and evaluated the controllers’ robustness under increasing and decreasing rotor resistance. The ensuing subsections present the simulation results for each scenario, with a comparison of PI, T1-FLC, and T3-FLC and key performance metrics such as , , , , and taken into account.

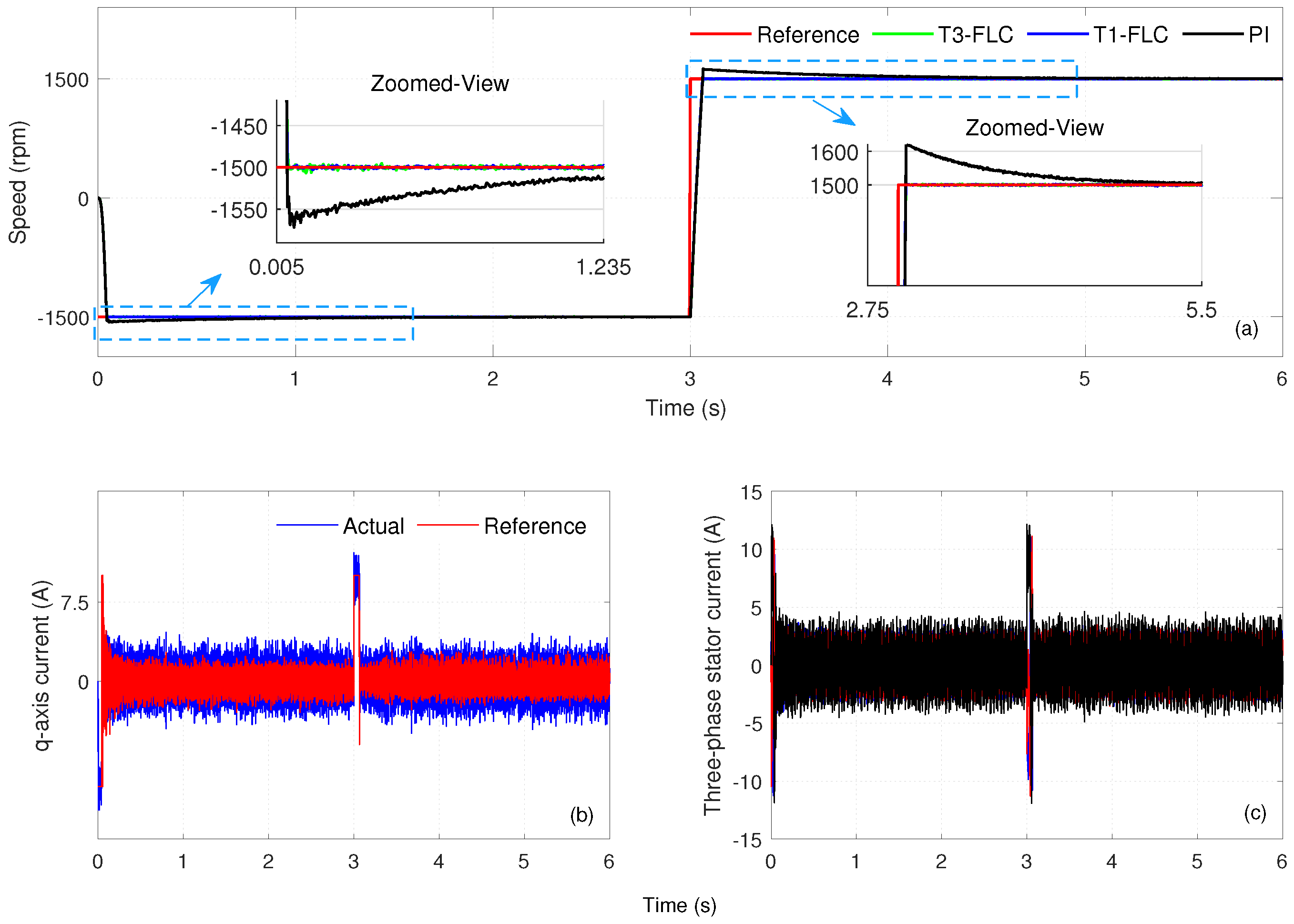

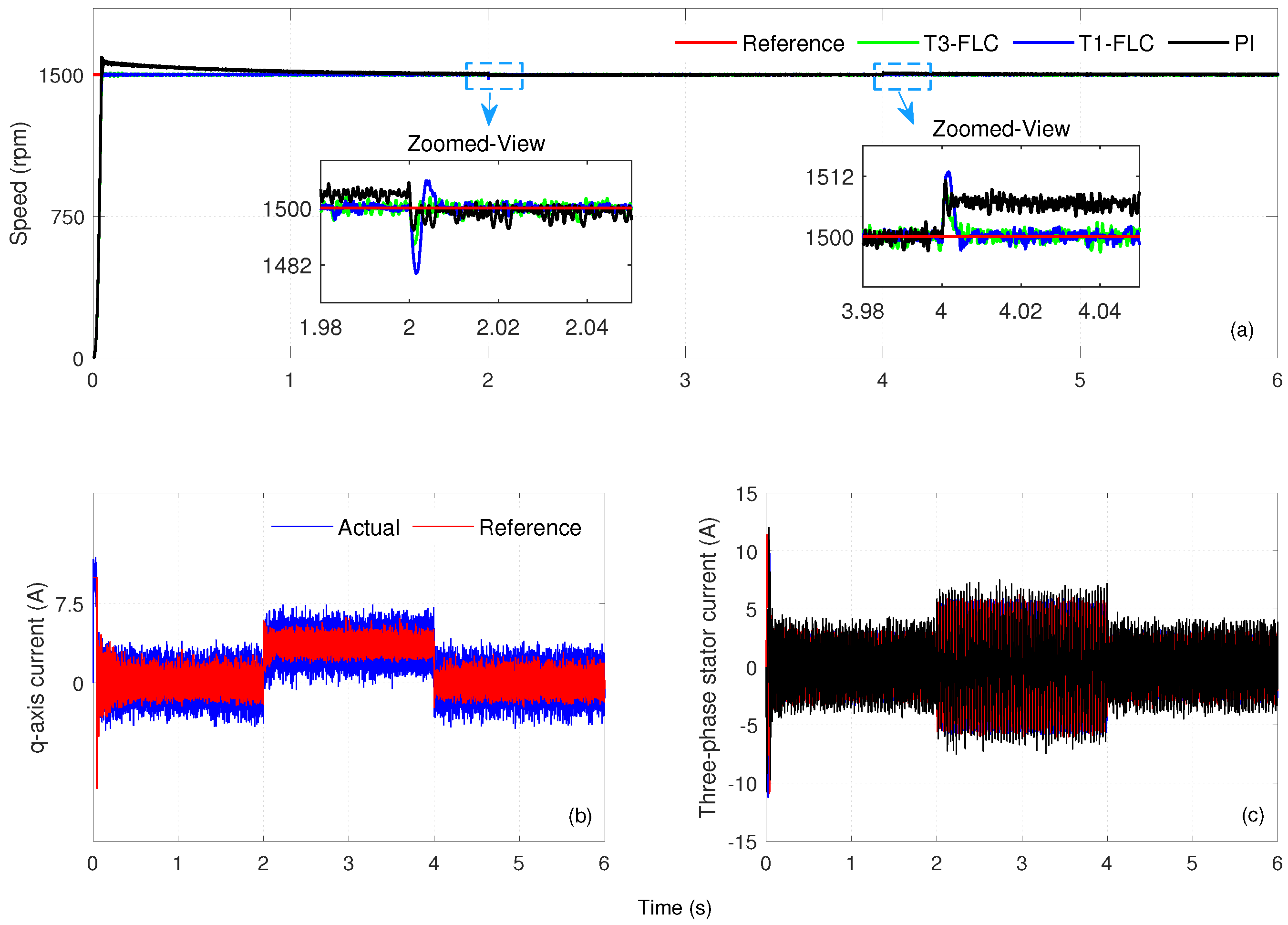

6.1.1. Case Study 1: High-Speed Reference Change

Under this operating condition, the reference speed was initially set to

and was changed to

at

. Simulation results obtained within Case Study 1 are presented in

Figure 3.

Figure 3a compares the motor speed responses obtained under the PI, T1-FLC, and T3-FLC controllers. The

q-axis current and three-phase currents for the T3-FLC alone are presented in

Figure 3b,c, respectively. The numerical performance metrics of the controllers, namely

,

, and

, are summarized in

Table 2.

In the 0–3 s range, T3-FLC responded quickly, with s and s, and the overshoot rate was recorded as . T1-FLC showed similar performance, with s and s, keeping the overshoot at . The PI controller, on the other hand, exhibited a longer transient regime, with s but with s and overshoot at .

In the 3–6 s range, T3-FLC produced s, s, and an overshoot of . T1-FLC produced s, s, and an overshoot of . The PI controller showed the longest settling time and the highest overshoot, with s, s, and overshoot . T3-FLC demonstrated balanced performance, with low overshoot and a short settling time. T1-FLC achieved a smaller overshoot in the low-speed range, but overshoot increased at high-speed transitions. The PI controller was limited by high overshoot and long settling times in both cases. All three controllers achieved zero steady-state error.

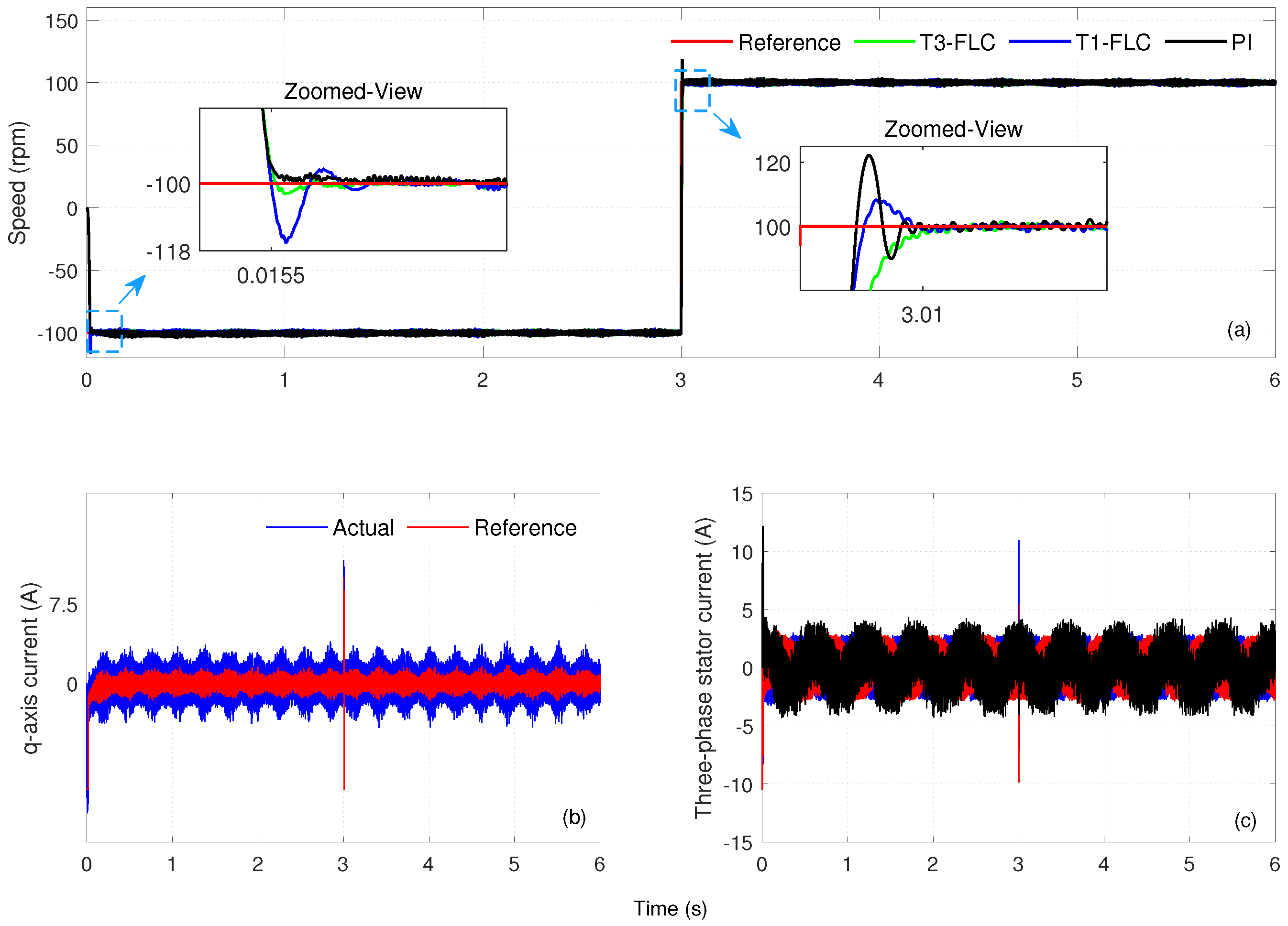

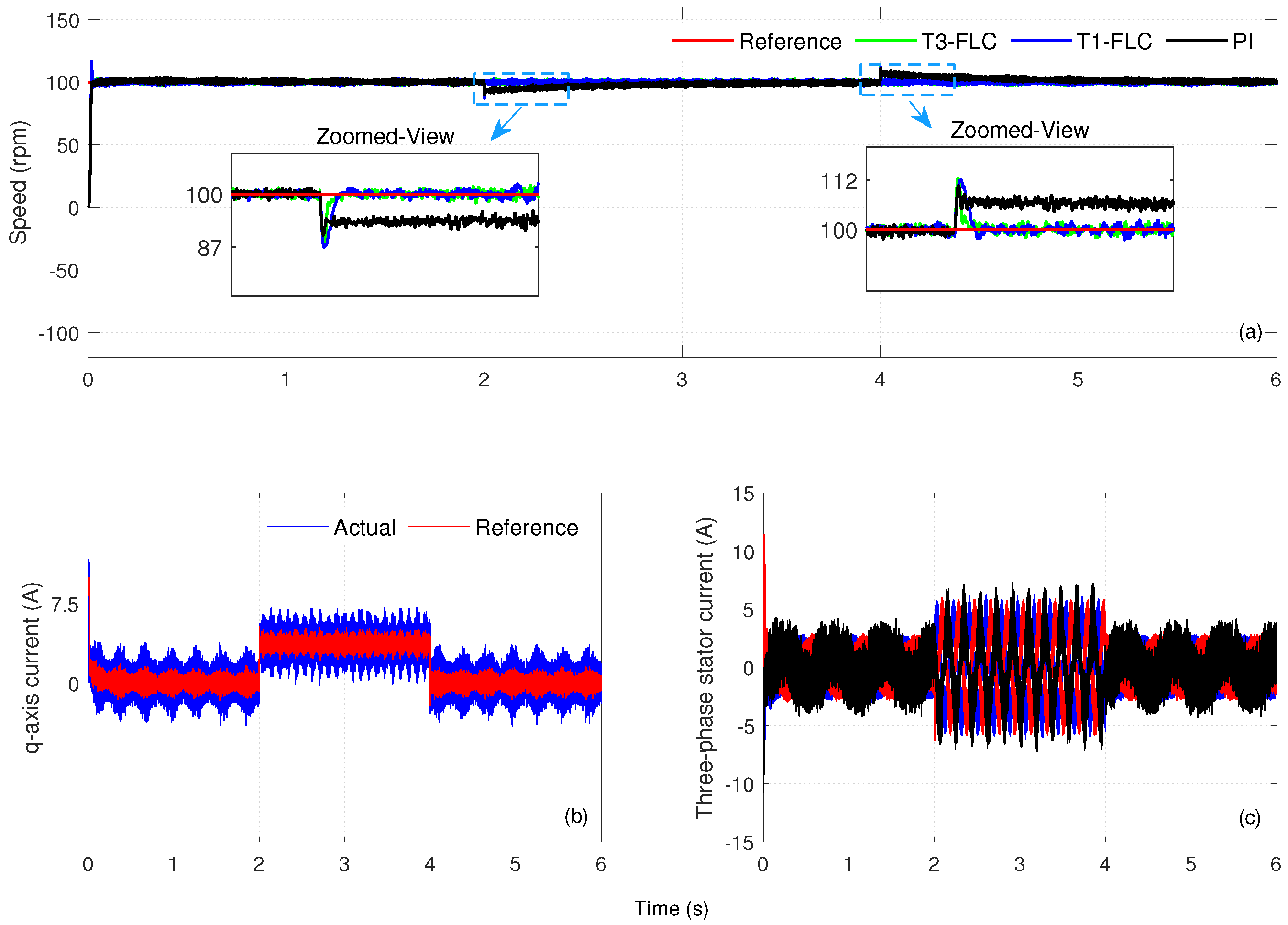

6.1.2. Case Study 2: Low-Speed Reference Change

Under this operating condition, the speed reference was set to

in the range 0–3 s and was abruptly changed to

at time

s. Simulation results obtained from Case Study 2 are presented in

Figure 4.

Figure 4a compares the speed responses obtained under the PI, T1-FLC, and T3-FLC controllers. The

q-axis current and motor three-phase currents for the T3-FLC alone are presented in

Figure 4b,c, respectively. Numerical performance metrics for the controllers

,

, and

are summarized in

Table 3.

In the 0–3 s range, T3-FLC produced a fast response with s and s, with an overshoot of . T1-FLC responded similarly quickly, with s and s, but its overshoot reached the highest value with . The PI controller exhibited similar times, with s and s, but its overshoot was . These results show that in the low-speed range, T3-FLC exhibited stable behavior by limiting the overshoot.

In the 3-to-6 s range, T3-FLC operated with values of s and s, with the overshoot remaining at a minimum of . T1-FLC responded with similar response times, with s and s, but overshoot occurred at . The PI controller operated with s and s, and its overshoot was greatest at . The results reveal that T3-FLC provided the smallest overshoot at low-amplitude reference changes, while the PI controller exhibited limited stability due to the high overshoot. The results of Case Study 2 demonstrate that T3–FLC provides balanced performance at low-speed reference changes by limiting overshoot while maintaining comparable and . T1–FLC responds quickly but incurs a higher overshoot, whereas the PI controller suffers a stability disadvantage due to markedly higher overshoot in the positive step.

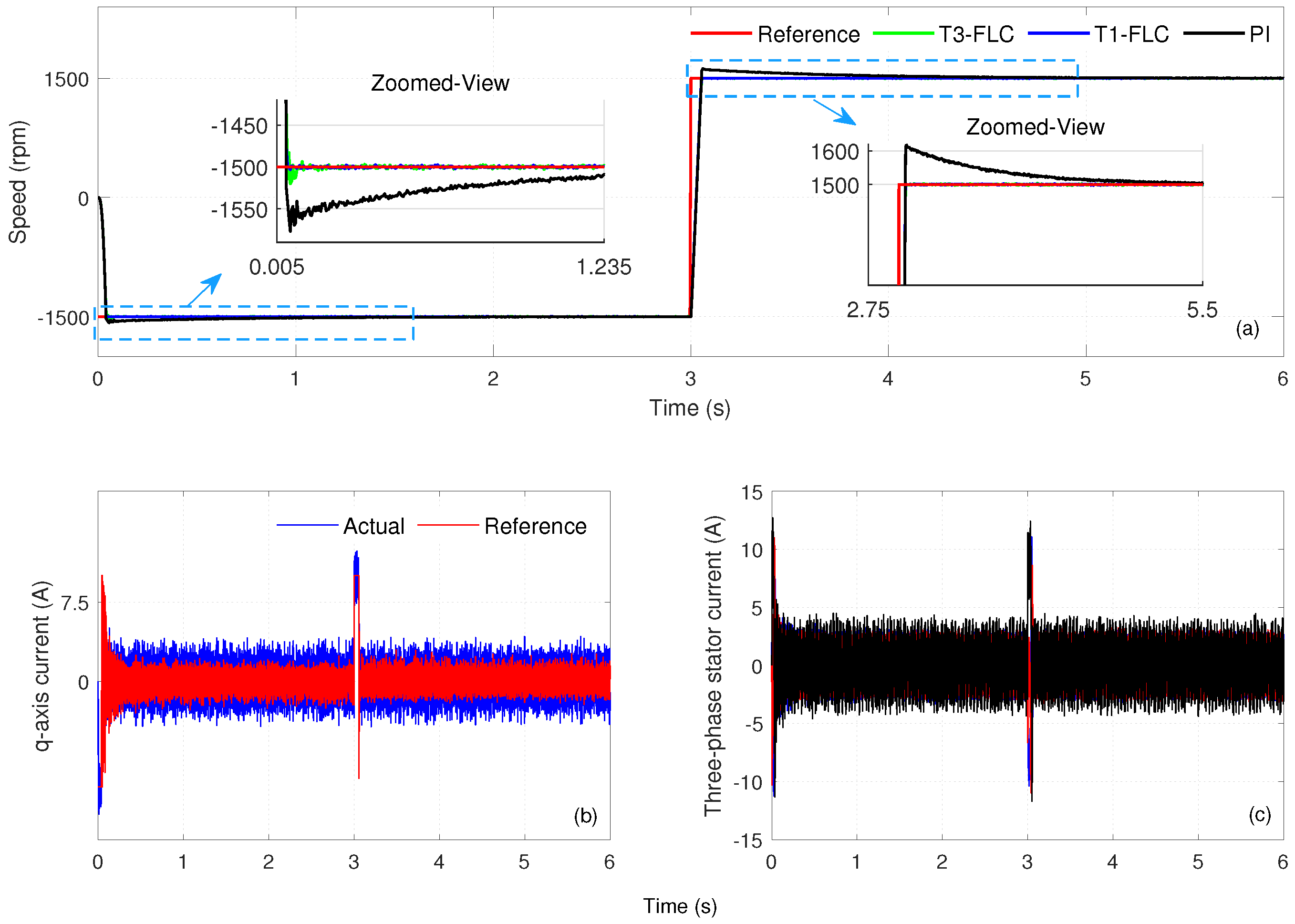

6.1.3. Case Study 3: Loaded Operation at High Speeds

Under these operating conditions, the reference speed was set as

and a load torque of

Nm was applied in the

–4 s range. Thus, the disturbance-rejection capability of the external speed-control loop in the high-speed regime was investigated. The simulation results obtained within the scope of Case Study 3 are presented in

Figure 5. The motor-speed responses obtained from the PI controller, T1-FLC, and T3-FLC are given comparatively in

Figure 5a, while the

q-axis current and three-phase currents for T3-FLC are shown in

Figure 5b,c, respectively. The numerical performance metrics for the controllers, such as

,

, and

, are summarized in

Table 4.

At s, when the load torque was applied, T3-FLC reduced the recovery time to s, with a peak error of and equal to zero. T1-FLC produced a longer recovery time and a higher peak error with values of s and , while the steady-state error remained zero. The PI controller reached a value of s, with the peak error recorded as at s and . These results show that T3-FLC provided the shortest recovery time at the moment of load application, while the PI controller offers a certain advantage by producing a lower peak error. When the load torque was removed at s, T3-FLC operated with a recovery time of s, a peak error measured at at s, and a steady-state error remaining at zero. Although T1-FLC achieved the same recovery time ( s), the peak error reached at s. The PI controller exhibited the longest recovery time ( s), with the peak error recorded as at s and the steady-state error remaining at zero. These findings reveal that T3-FLC provides a balanced response in terms of both recovery time and error magnitude during load removal. At high speeds and under load, T3-FLC stands out for its short recovery time and low error values. While T1-FLC kept the steady-state error at zero, it fell behind T3-FLC in terms of recovery time and peak error. Although the PI controller can produce lower peak error at some moments, the long recovery time limits the ability to detect disturbance rejection.

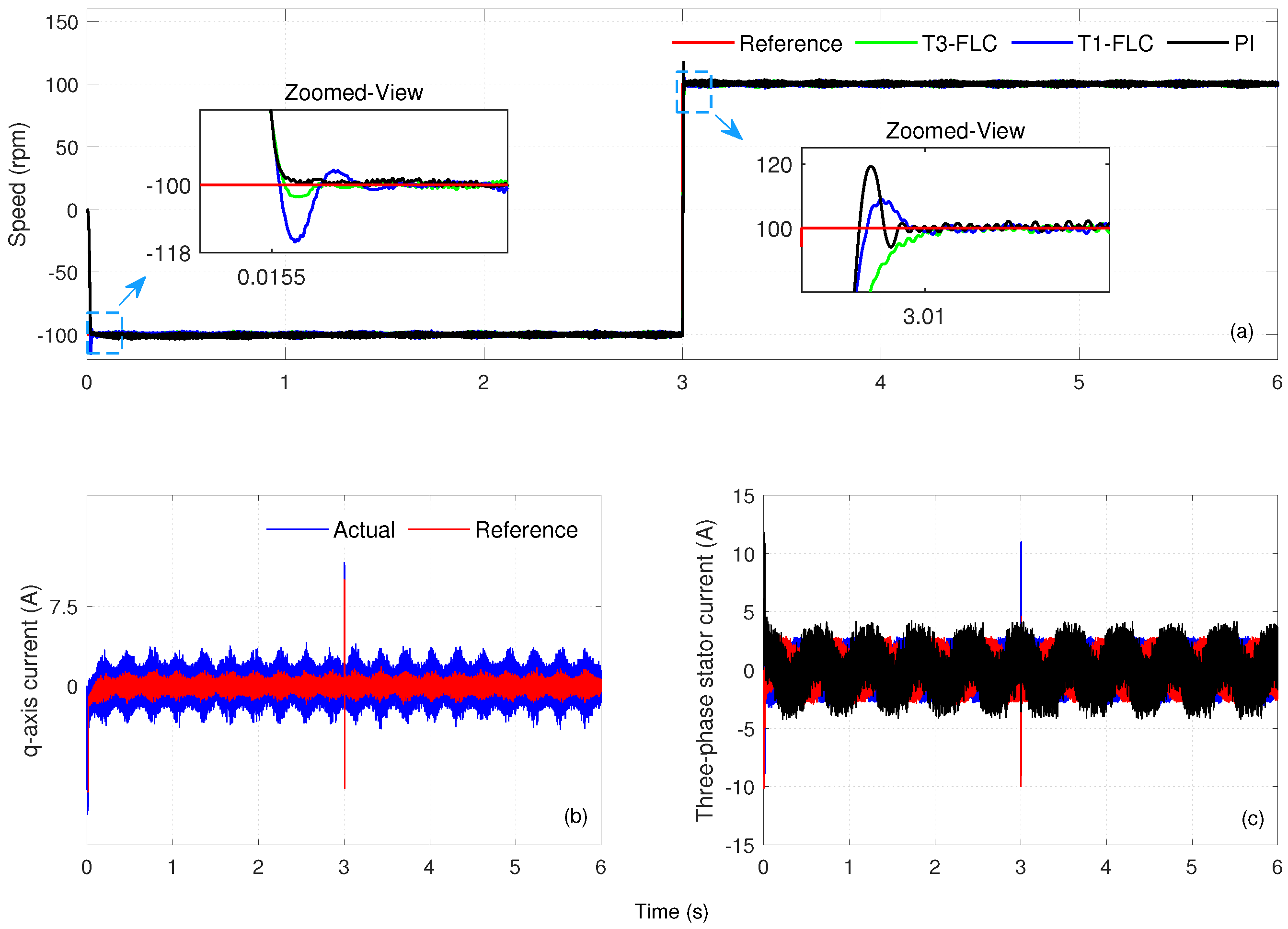

6.1.4. Case Study 4: Loaded Operation at Low Speed

Under these operating conditions, the reference speed was set as

and a load torque of

Nm was applied in the

–4 s range. Thus, the disturbance-rejection capability of the external speed-control loop in the low-speed regime was investigated. The simulation results obtained within the scope of Case Study 4 are presented in

Figure 6. The motor-speed responses obtained with the PI, T1-FLC, and T3-FLC controllers are given comparatively in

Figure 6a, while the

q-axis current and three-phase currents for T3-FLC are shown in

Figure 6b,c, respectively. The numerical performance metrics of the controllers,

,

and

, are summarized in

Table 5.

When the load torque was applied at s, T3-FLC kept the recovery time at s, the peak error at , and the steady-state error at zero. T1-FLC achieved a shorter recovery time ( s), but the peak error was higher than that of T3-FLC, at . The PI controller had a significantly longer recovery time ( s), a peak error recorded as , and a steady-state error of zero. These findings show that although the PI controller produces low peak error during load application, its recovery speed is poor, while T3-FLC and T1-FLC offer faster recovery. When the load moment is removed at s, T3-FLC provides a stable response, with a recovery time of s and a peak error of , while the steady-state error remains zero. T1-FLC exhibited similar performance, with s and . The PI controller exhibited the longest recovery time, with s, and yielded a peak error of and a steady-state error of zero. These results demonstrate that T3-FLC and T1-FLC recover faster than PI during load removal. At the same time, the PI controller suffers from a disadvantage due to its slow recovery time, despite its low peak error. The results of Case Study 4 show that in the low-speed regime, T3-FLC offers balanced performance, with its short recovery time and low error magnitude. Despite operating with similar recovery times, T1-FLC yielded a higher peak error than did T3-FLC. While the PI controller produced the lowest peak errors in both cases, its long recovery times limited its disturbance-rejection ability.

6.1.5. Case Study 5: Parameter Change at High Speed

In this scenario, the rotor resistance is increased by

and the speed reference is set to

at

and abruptly changed to

at

s.

Figure 7 presents the speed responses obtained with the PI, T1-FLC, and T3-FLC controllers are given comparatively in

Figure 7a, while the

q-axis current and three-phase currents for T3-FLC are shown in

Figure 7b,c, respectively. The

Table 6 summarizes performance metrics such as

,

, and

.

In the range of 0–3 s, T3-FLC produced a fast response, with s and s, and its overshoot was . T1-FLC operated at similar speeds, with s and s, and its overshoot was recorded as . The PI controller, on the other hand, stabilized significantly later, with s and s, and produced an overshoot of . In the 3–6 s range, T3-FLC exhibited a low overshoot of , with s and s, providing a stable response. T1-FLC performed similarly, with s and s, with overshoot remaining at . The PI controller had the longest settling time, with s and s, and its overshoot reached the highest value (). Under a 20% increase in rotor resistance, T3-FLC showed the most balanced performance against parameter uncertainties, with both low overshoot rates and short settling times. T1-FLC achieved a similar rise in settling times, but its overshoot value was higher than that of T3-FLC. The PI controller, on the other hand, exhibited limited tolerance to parameter changes due to longer settling times and higher overshoot values in both ranges.

6.1.6. Case Study 6: Parameter Change at Low Speed

In this scenario, the rotor resistance is reduced by

and the speed reference is set to

at

and abruptly changed to

at

s.

Figure 8 presents the speed responses obtained with the PI, T1-FLC, and T3-FLC controllers are given comparatively in

Figure 8a, while the

q-axis current and three-phase currents for T3-FLC are shown in

Figure 8b,c, respectively. The

Table 7 summarizes the quantitative performance metrics such as

,

, and

.

In the range of 0–3 s, T3-FLC responded quickly, with values of s and s, and its overshoot was recorded as . T1-FLC operated at a similar speed, with values of s and s, but its overshoot reached the highest value (). The PI controller operated with values of s and s, and its overshoot was recorded as . In the 3–6 s range, T3-FLC produced low overshoot (), with s and s. T1-FLC exhibited a shorter rise time ( s and s), but its overshoot reached . The PI controller operated with the values of s and s, and its overshoot was the highest (). Under the condition of a decrease in rotor resistance, T3-FLC stood out, with low overshoot and stable transition properties. Although T1-FLC provided similar rise and settling times in some cases, overshoot values remained high. The PI controller produced acceptable results in terms of settling times but exhibited limited resistance to parameter uncertainties due to high overshoot rates in low- and high-speed regions.