Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Remote Sensing Interpretation and a Blending-XGBoost-CNN Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data

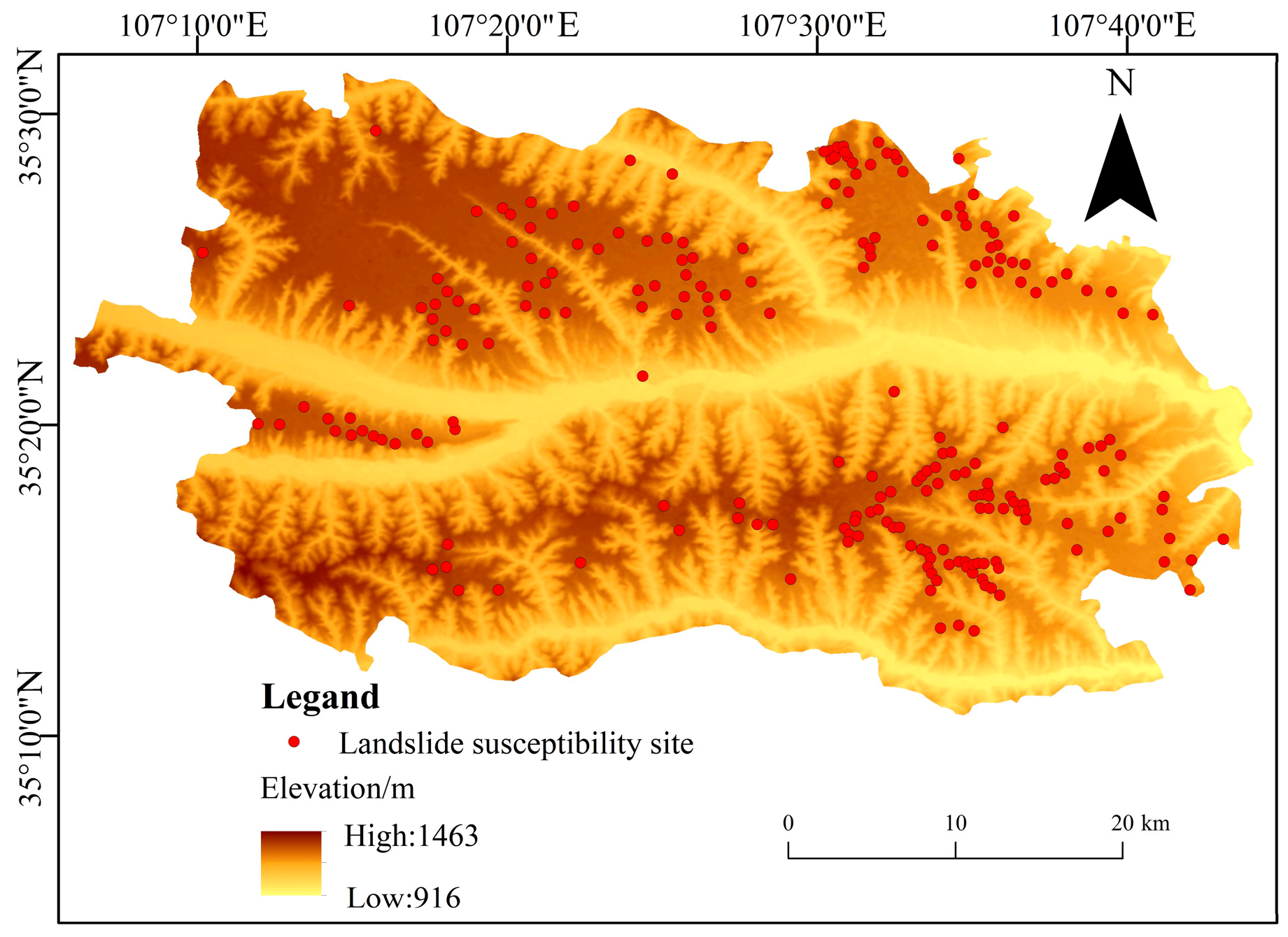

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

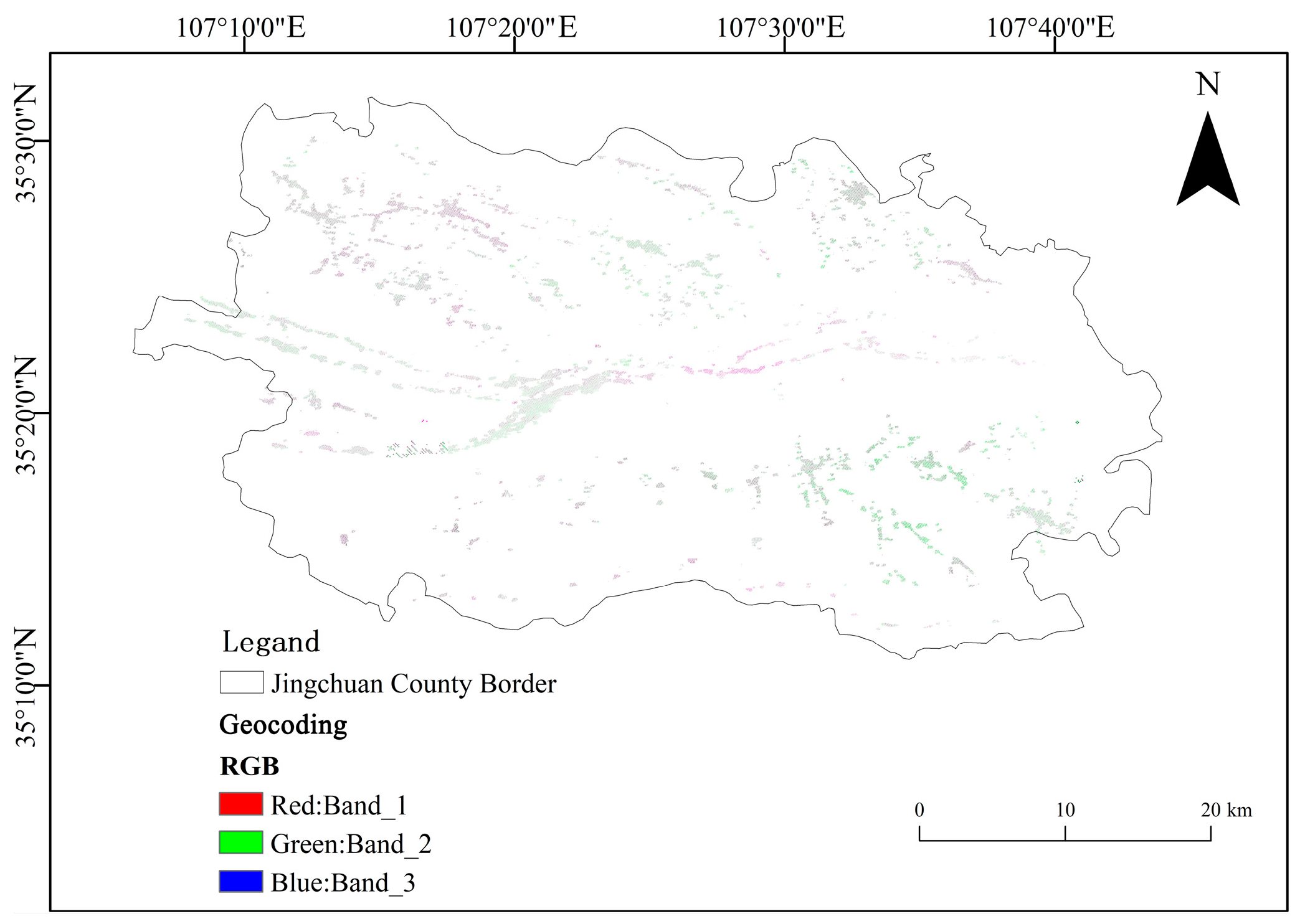

2.2. Study Data and Sources

3. Identification of Potential Landslides in the Study Area

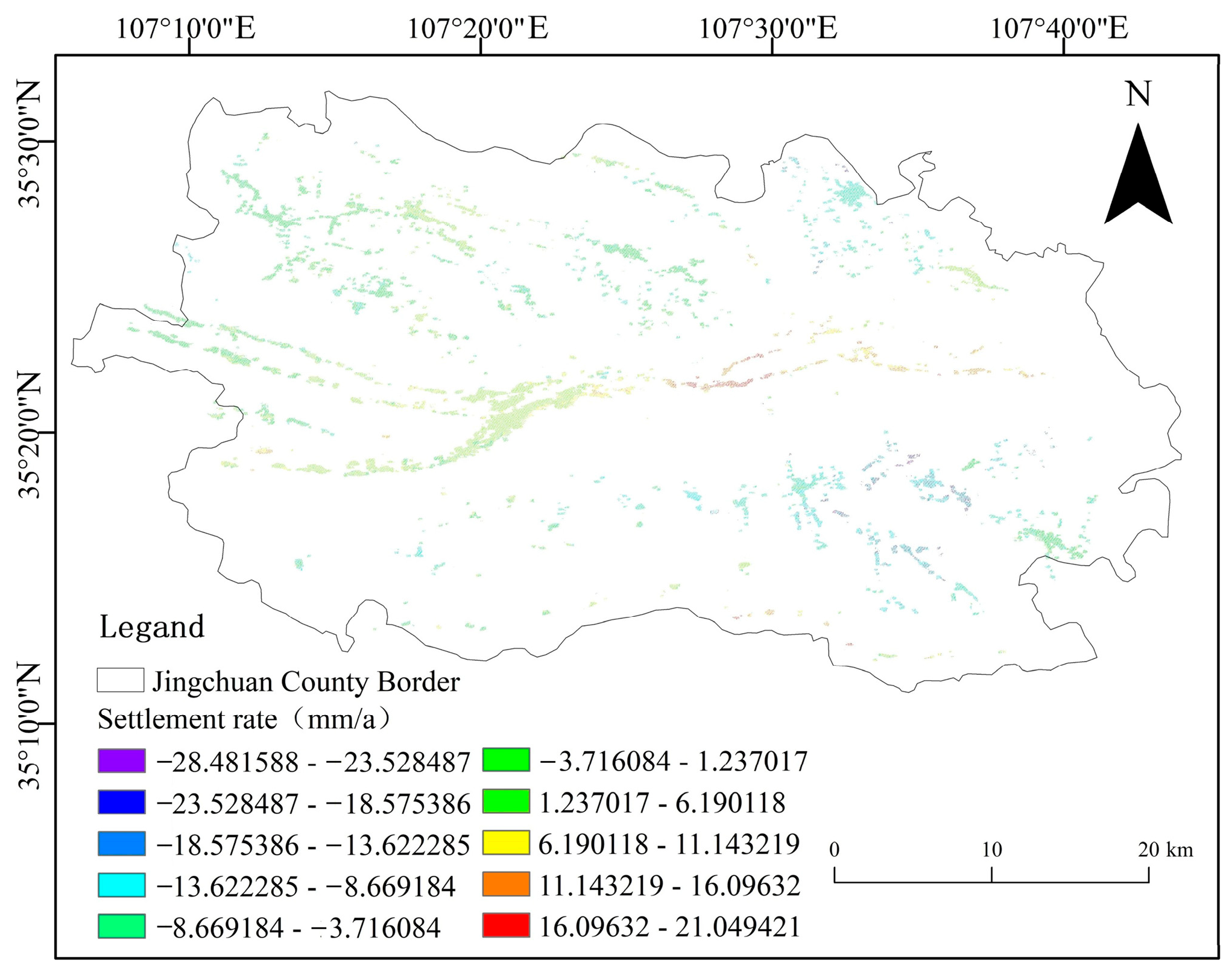

3.1. SBAS-InSAR

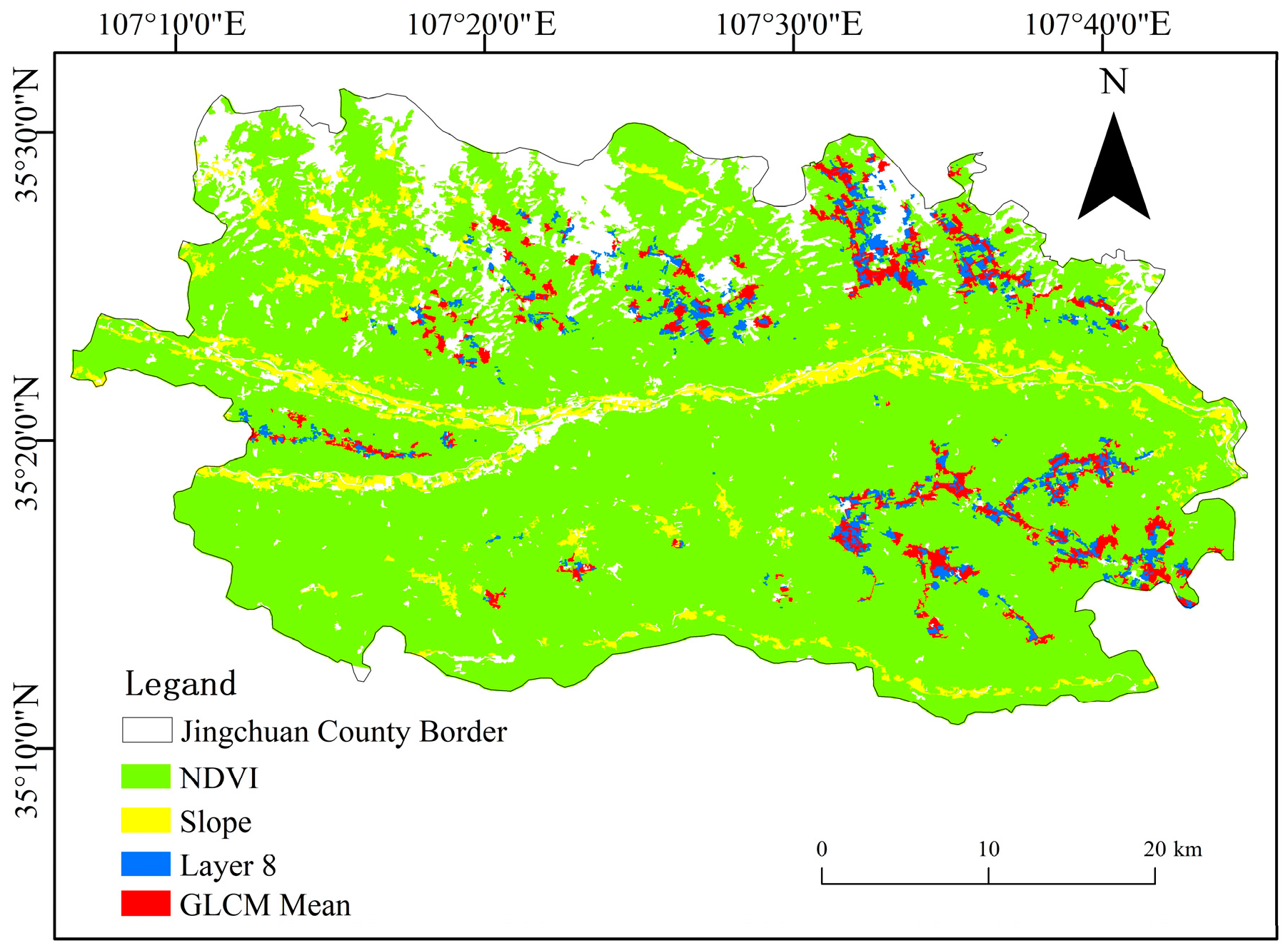

3.2. Object-Oriented Classification Method

3.3. Identification Results of Potential Landslides

4. LSM in the Study Area

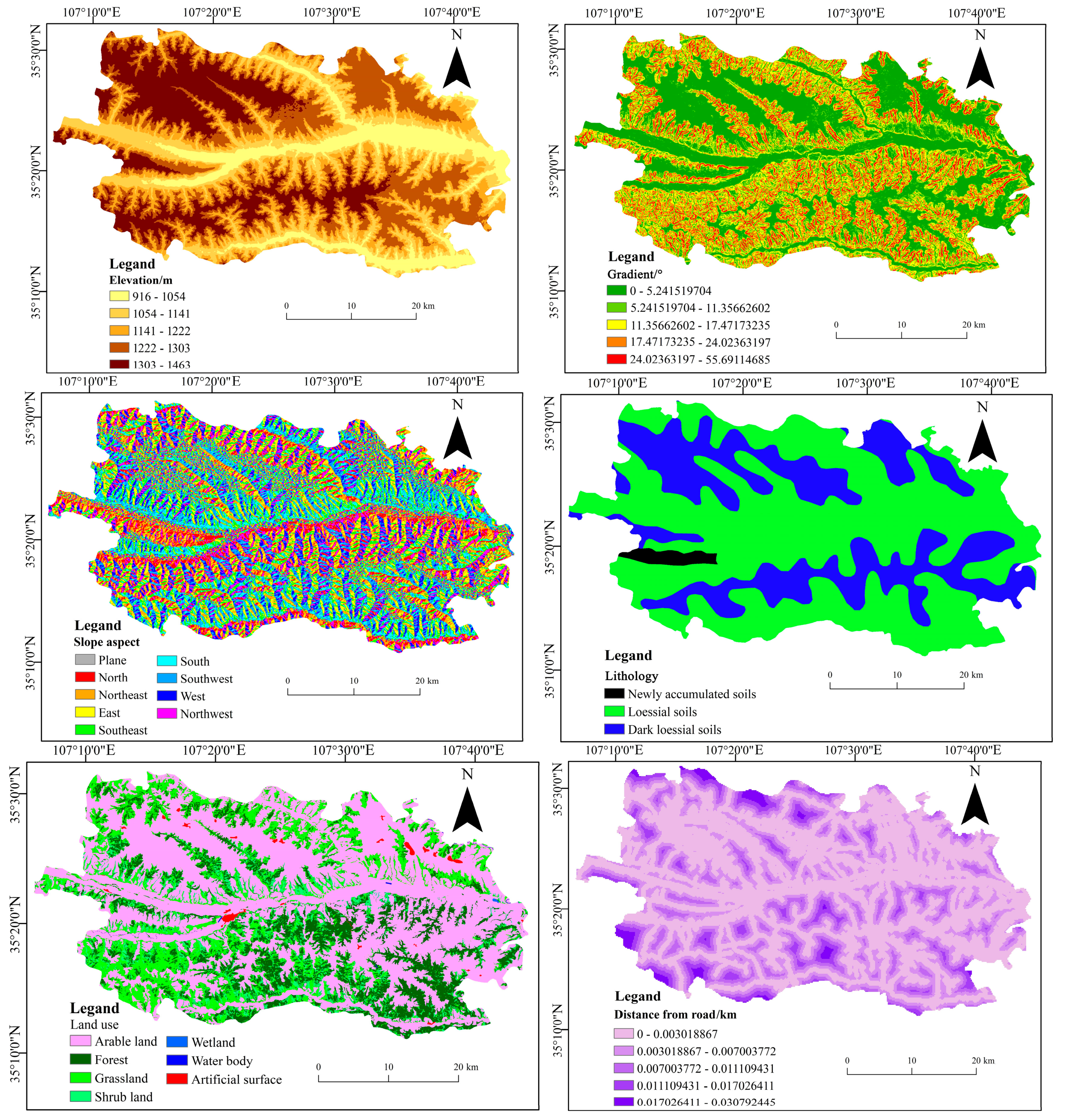

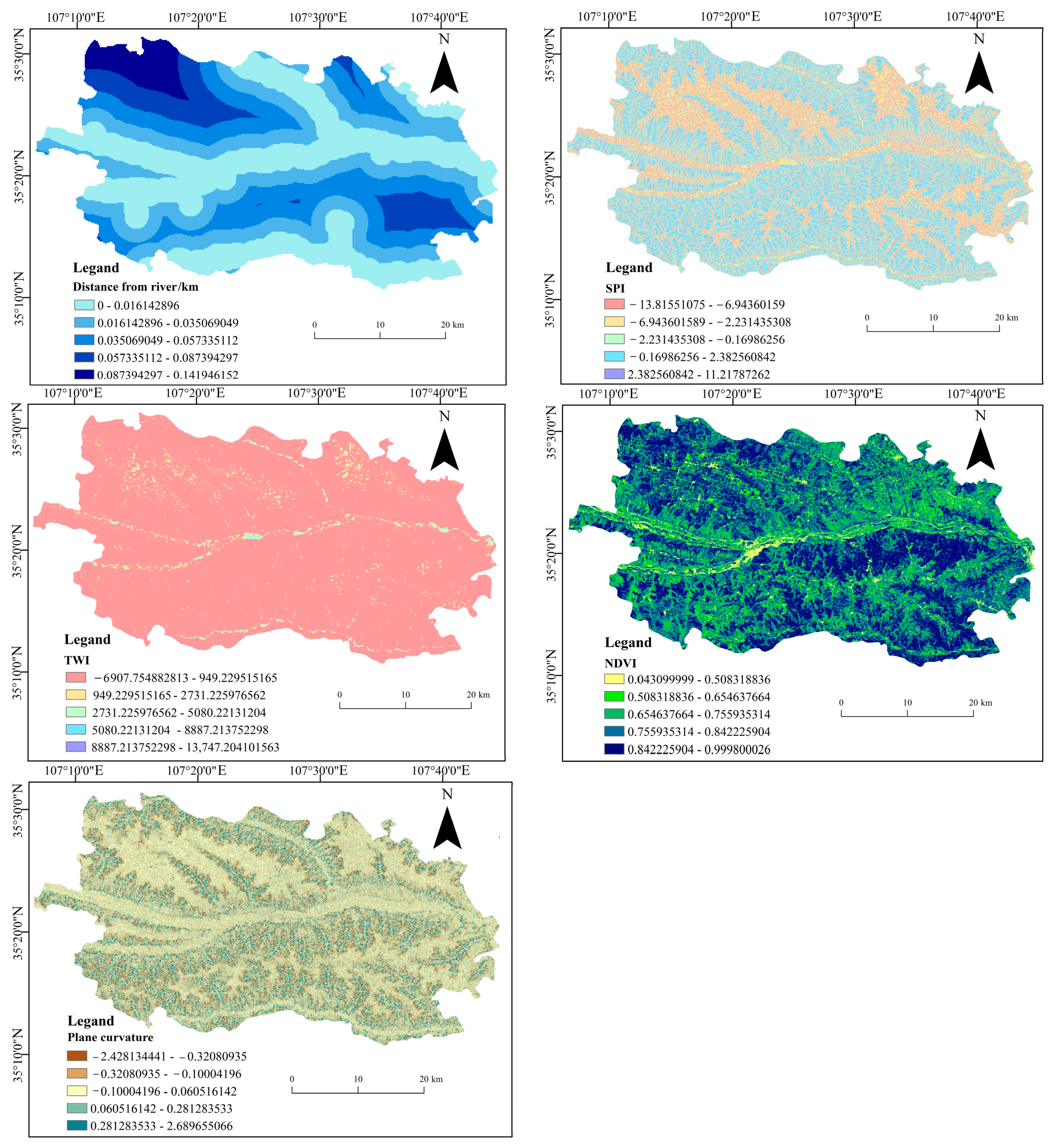

4.1. Selection of Hazard Factors

4.2. Model Overview

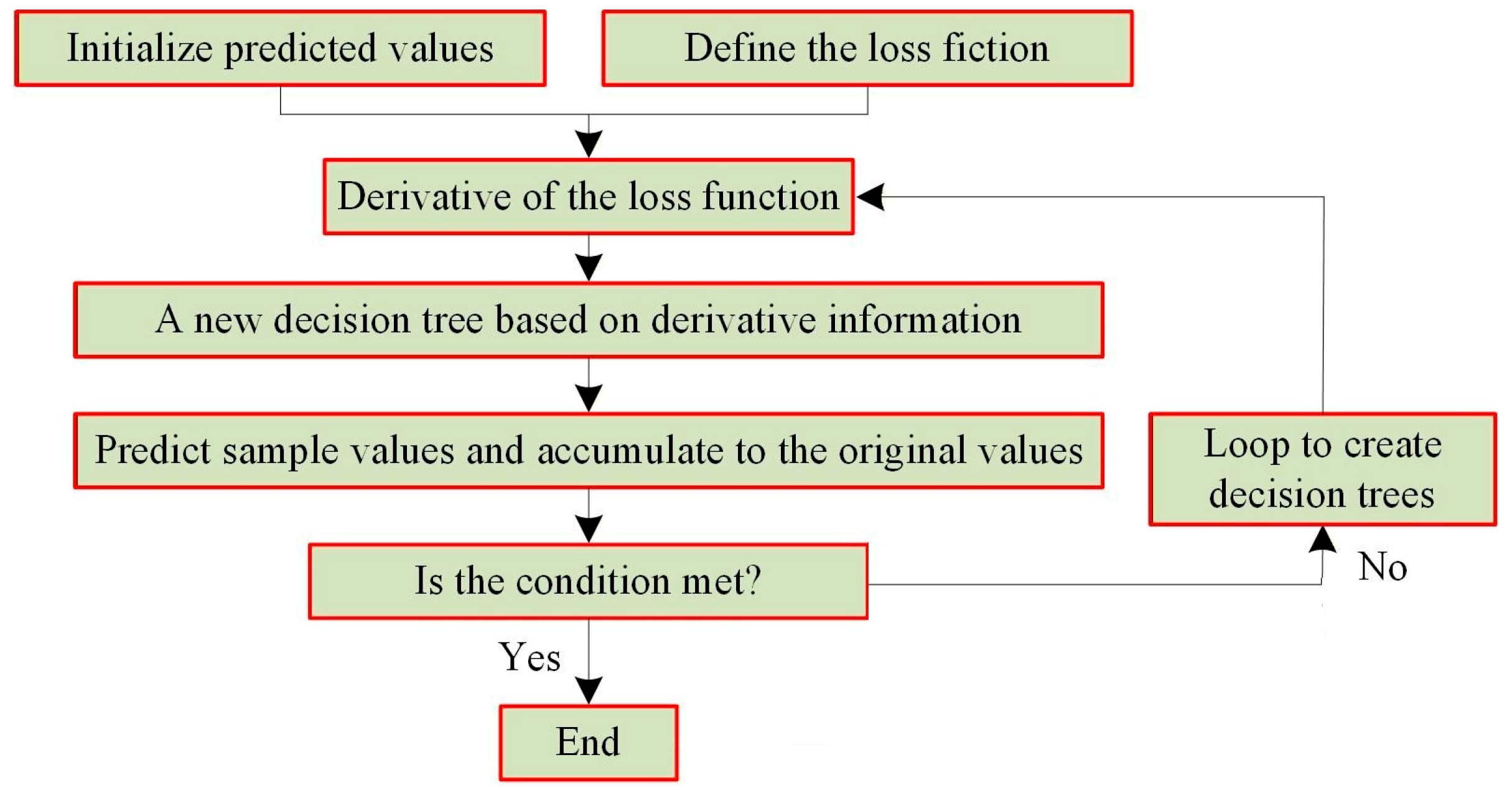

4.2.1. The XGBoost Model

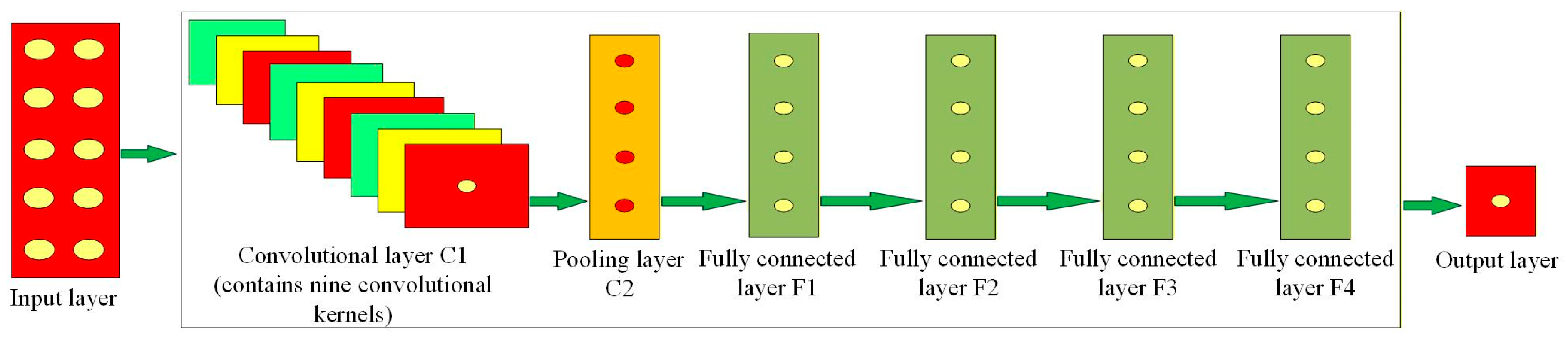

4.2.2. CNN Model

4.2.3. The Blending-XGBoost-CNN Model

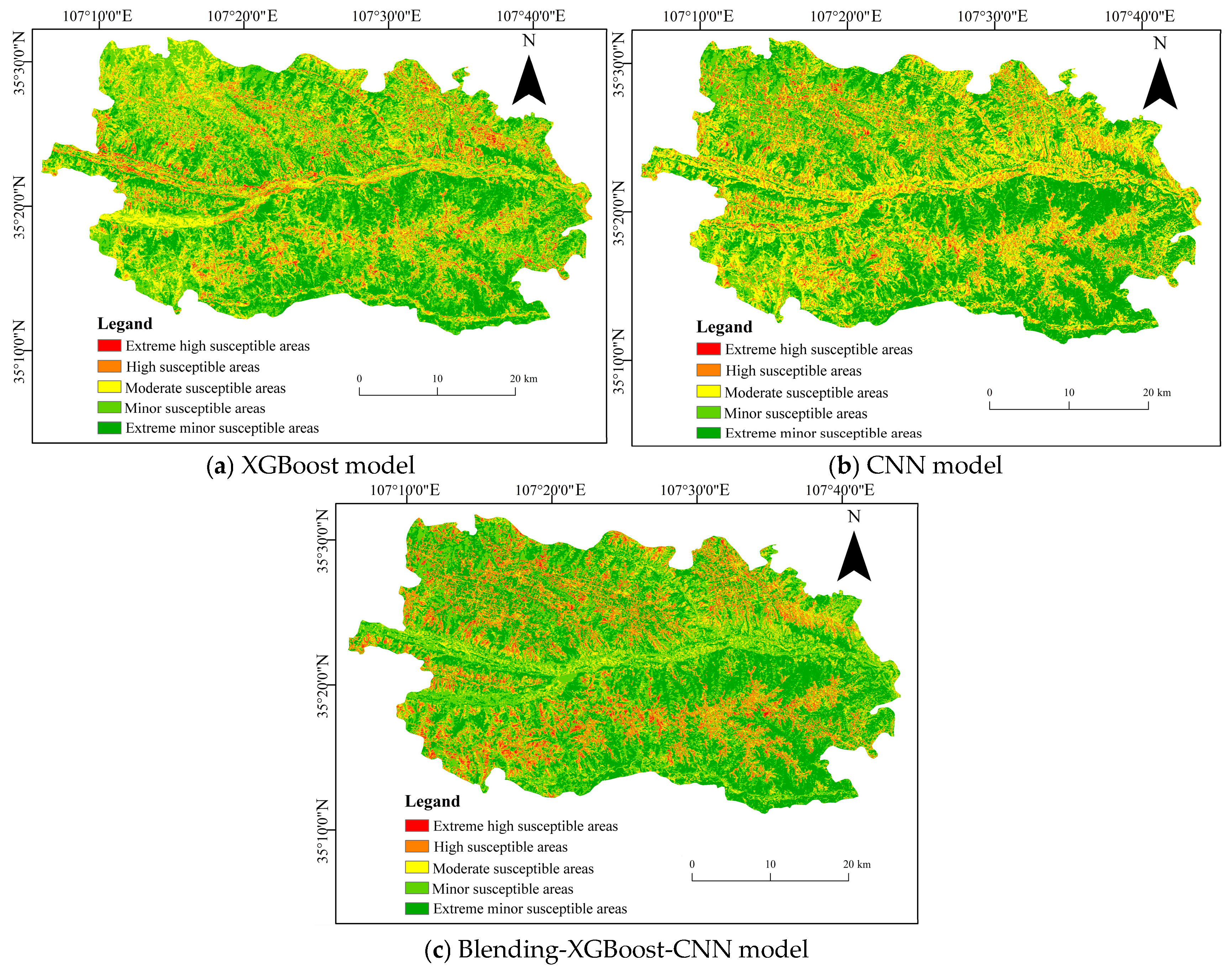

4.3. LSM Results

5. Discussions

5.1. Factor Detector

5.2. Interaction Detector

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Longoni, L.; Scaioli, A.; Panzeri, L.; Arosio, D.; Corti, M.; Hojat, A.; Papini, M. A new Landslide Investigation and Simulation Archive through downscaled landslide experiments. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Tian, W.B.; Che, F.; Guo, B.; Wang, S.P.; Jia, Z.R. Model tests and numerical simulations on hydraulic fracturing and failure mechanism of rock landslides. Nat. Hazards 2023, 115, 1977–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.; Luu, B.T.; Nguyen, D.H.; Le, T.H.T.; Pham, S.V.; Thi, N.V. A study of non-landslide samples and weights for mapping landslide susceptibility using regression and clustering methods. Earth Sci. Inform. 2023, 16, 4009–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.C.; Zêzere, J.L.; Garcia, R.A.C.; Pereira, S.; Vaz, T.; Melo, R. Landslide susceptibility assessment using different rainfall event-based landslide inventories: Advantages and limitations. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 9361–9399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Ji, P.K.; Liu, S.Y.; Zhao, J.Z.; Yang, Y.M. Susceptibility evaluation of highway landslide disasters based on SBAS-InSAR: A case study of S211 highway in Lanping County. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 2587–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.J.; Zeng, T.R.; Yin, K.L.; Gui, L.; Guo, Z.Z.; Wang, T.F. Dynamic landslide susceptibility mapping based on the PS-InSAR deformation intensity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 7872–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Chen, J.P.; Tan, C.; Li, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.S.; Yan, J.H. Deformation and potential failure analysis of a giant old deposit in the southeastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau based on SBAS-InSAR and numerical simulation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.S.; Lu, W.J.; Jiang, R.C.; Li, J.H.; Zhang, L.M. Analysis of landslide on Meizhou-Dapu expressway based on satellite remote sensing. Geoenviron. Disasters 2025, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpitha, G.A.; Choodarathnakara, A.L.; Rajaneesh, A.; Sinchana, G.S.; Sajinkumar, K.S. Creation of a Landslide Inventory for the 2018 Storm Event of Kodagu in the Western Ghats for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Machine Learning. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2024, 52, 2443–2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Wang, J.Z.; Mao, X.; Zhao, Z.A.; Gao, X.Y.; Lu, W.J. An Improved Faster R-CNN Method for Landslide Detection in Remote Sensing Images. J. Geovis. Spat. Anal. 2023, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.Q.; Guo, C.B.; Zhang, Y.N.; Song, D.G.; Qiu, Z.D. Comprehensive evaluation and prediction of potential long-runout landslide in Songrong, Tibetan Plateau: Insights from remote sensing interpretation, SBAS-InSAR, and Massflow numerical simulation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, N.; Vaidya, H. Automated detection of landslide events from multi-source remote sensing imagery: Performance evaluation and analysis of YOLO algorithms. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 133, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.K.; Ranirez, R.A.; Lim, H.H.; Kwon, T.H. Multi-source remote sensing-based landslide investigation: The case of the August 7, 2020, Gokseong landslide in South Korea. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handwerger, A.L.; Lacroix, P.; Bell, A.F.; Booth, A.M.; Huang, M.H.; Mudd, S.M.; Bürgmann, R.; Fielding, E.J. Multi-sensor remote sensing captures geometry and slow-to-fast sliding transition of the 2017 Mud Creek landslide. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.W.; Chen, D.N.; Dong, Y.H.; Xue, Y.M.; Qin, K.X. Identification of potential landslide in Jianzha county based on InSAR and deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Li, H.R.; Che, F.; Li, Y.; Liu, D. Susceptibility mapping and zoning of highway landslide disasters in China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.C.; Liu, P.; Deng, H.; Liu, Z.K.; Li, L.J.; Wang, Y.S.; Ai, Q.X.; Liu, J.X. A Novel Approach to Three-Dimensional Inference and Modeling of Magma Conduits with Exploration Data: A Case Study from the Jinchuan Ni-Cu Sulfide Deposit, NW China. Nat. Resour. Res. 2023, 32, 901–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, S.A.; Xu, J.D.; Tao, Z.G.; Wu, M.L.; Li, D.X.; Zhang, G.H.; Liu, Y.P.; Wang, F.N.; et al. Hydraulic Fracturing In-Situ Stress Measurements and Large Deformation Evaluation of 1000m-Deep Soft Rock Roadway in Jinchuan No. 2 Mine, Northwestern China. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 2781–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, J.L.; Xie, X.S.; Hong, H.Y.; Trung, N.V.; Bui, D.T.; Wang, G.; Li, X.R. Spatial prediction of landslide susceptibility using integrated frequency ratio with entropy and support vector machines by different kernel functions. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Zhang, X.; Xie, J.C.; Liang, J.C.; Wang, T.T. Study on hydrological response of runoff to land use change in the Jing River Basin, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 101075–101090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.W.; Chen, J.P.; Wang, G.H.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Y.W. Mining Subsidence Based on Integrated SBAS-InSAR and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Technology. J. Ocean Univ. China 2025, 24, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, Z.; Zhao, C.; Ijaz, N.; Rehman, Z.; Ijaz, A. Novel application of Google earth engine interpolation algorithm for the development of geotechnical soil maps: A case study of mega-district. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 18196–18216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Li, Z.W.; Xu, B.; Jiang, W.P.; Cao, Y.M.; Xiong, Y.; Wei, J.C. Turbulent atmospheric phase correction for SBAS-InSAR. J. Geod. 2024, 98, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Gao, J.; Gao, F.Z. Time series land subsidence monitoring and prediction based on SBAS-InSAR and GeoTemporal transformer model. Earth Sci. Inform. 2024, 17, 5899–5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Q.X.; Liu, R.X.; Li, X.P.; Gao, T.F.; Chen, Y.; Xiao, Y.X.; He, H.Z.; Wei, Y.G. A method for monitoring three-dimensional surface deformation in mining areas combining SBAS-InSAR, GNSS and probability integral method. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Hu, X.N.; Lin, B.; Meng, F.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J. Detection and Monitoring of Potential Geological Disaster Using SBAS-InSAR Technology. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 27, 4884–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, N.; Singh, S.; Gupta, S. Comparative Analysis and Implication of Hyperion Hyperspectral and Landsat-8 Multispectral Dataset in Land Classification. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2023, 51, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, S.V.; Olatunji, A.S.; Umaru, A.O.; Olisa, O.G.; Reyoug, S.S.; Hamoud, A. Lithological, structural, and alteration mapping of uraniferous granitoid using Landsat 8, in the oriental part of the Reguibat shield, northern Mauritania. Arab. J. Geosci. 2024, 17, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Dahiya, N.; Sood, V.; Singh, S.; Sharma, A. ENVINet5 deep learning change detection framework for the estimation of agriculture variations during 2012-2023 with Landsat series data. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjithkumar, S.; Anbazhagan, S.; Tamilarasan, K. Image Processing of Landsat-8 OLI Satellite Data for Mapping of Alkaline-Carbonatite Complex, Southern India. Remote Sens. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 7, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Uddin, M.K.; Tan, Y.M. Remote sensing-based changes in the Ukhia Forest, Bangladesh. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 4269–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jombo, S.; Adelabu, S. Evaluating Landsat-8, Landsat-9 and Sentinel-2 imageries in land use and land cover (LULC) classification in a heterogeneous urban area. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Cao, Y.; Meena, S.R.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Y. Utilizing deep learning approach to develop landslide susceptibility mapping considering landslide types. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.M.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, B.C.; Chang, Z.L.; Zhou, C.B.; Jiang, S.H.; Huang, J.S.; Catani, F.; Yu, C.S. Effects of different division methods of landslide susceptibility levels on regional landslide susceptibility mapping. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2025, 84, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.B.; Yin, C.; Tan, Z.Y.; Liu, X.L.; Li, S.F.; Ma, X.B.; Zhang, X.X. Landslide Susceptibility Assessment Considering Time-Varying of Dynamic Factors. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2024, 25, 05024004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, Z.; Zhao, C.; Ijaz, N.; Rehman, Z.; Ijaz, A. Development and optimization of geotechnical soil maps using various geostatistical and spatial interpolation techniques: A comprehensive study. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Deng, H.W.; Li, Y.Y.; Pan, Z.; Peng, T. Enhancing landslide susceptibility modelling through predicted InSAR deformation rates. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 84, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Wang, Z.H.; Zhao, X.K. Spatial prediction of highway slope disasters based on convolution neural networks. Nat. Hazards 2022, 113, 813–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.F.; Yin, C.; Li, J.X.; Sun, T.Q. Landslide susceptibility assessment based on remote sensing interpretation and DBN-MLP model: A case study of Yiyuan County. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2025, 39, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Deng, H.W. The impact of different sampling strategies on landslide susceptibility assessment: An explainable hybrid BO-XGBoost model. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.P.; Ji, S.J.; Li, H.Z.; Zhu, C.Q.; Zou, Y.Y.; Ni, B.; Gu, Z.A. Classification forecasting research of rock burst intensity based on the BO-XGBoost-Cloud model. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavzoglu, T.; Teke, A. Predictive Performances of Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithms in Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Random Forest, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and Natural Gradient Boosting (NGBoost). Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 7367–7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, E.K. Implementation of free and open-source semi-automatic feature engineering tool in landslide susceptibility mapping using the machine-learning algorithms RF, SVM, and XGBoost. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 1067–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.G.; Yin, C.; Sun, T.Q.; Li, J.X. Seismic Damage Risk Assessment of Reinforced Concrete Bridges Considering Structural Parameter Uncertainties. Coatings 2025, 15, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.H.; Gan, J.J.; Chen, A.B.; Acharya, P.; Li, F.H.; Yu, W.J.; Liu, F.Z. A Novel Method for Identifying Landslide Surface Deformation via the Integrated YOLOX and Mask R-CNN Model. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.M.; Wang, C.Y.; Wen, Z.Z.; Gao, J.; Xia, M.F. Landslide displacement prediction based on the ICEEMDAN, ApEn and the CNN-LSTM models. J. Mt. Sci. 2023, 20, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Nguyen, M.D.; Nguyen, T.V.; Cao, C.T.; Phong, T.V.; Duc, D.M.; Bien, T.X.; Prakash, I.; Le, H.V.; Pham, B.T. Enhanced Landslide Spatial Prediction Using Hybrid Deep Learning Model and SHAP Analysis: A Case Study of the Tuyen Quang-Ha Giang Expressway, Vietnam. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2024, 53, 1647–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Das, S.; Saha, A. Exploring uncertainty analysis in GIS-based Landslide susceptibility mapping models using machine learning in the Darjeeling Himalayas. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqadhi, S.; Mallick, J.; Alkahtani, M.; Ahmad, I.; Alqahtani, D.; Hang, H.T. Developing a hybrid deep learning model with explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) for enhanced landslide susceptibility modeling and management. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 3719–3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Mani, A.; Lall, A.R.; Kumar, D. Slope stability assessment and landslide susceptibility mapping in the Lesser Himalaya, Mussoorie, Uttarakhand. Discov. Geosci. 2024, 2, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Qin, S.W.; Zhang, C.B.; Yao, J.Y.; Xing, Z.Y.; Cao, J.S.; Zhang, R.C. Landslide susceptibility assessment based on frequency ratio and semi-supervised heterogeneous ensemble learning model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 32043–32059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.D.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, S.H.; Sun, P.H.; Liu, L.L.; Peng, Z.W. Comparative study of sampling strategies for machine learning-based landslide susceptibility assessment. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2024, 38, 4935–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K.; Wanjari, N.; Misra, A.K. Landslide susceptibility assessment in Sikkim Himalaya with RS & GIS, augmented by improved statistical methods. Arab. J. Geosci. 2024, 17, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L.; Zhou, J.L.; Wang, Z.G.; Yang, Y.T.; Lu, J.Y.; Kang, D.J.; Wang, S.H.; Zhang, H. Assessment of landslide susceptibility in watersheds during extreme rainfall using a complex network of slope units. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Song, D.Q.; Dong, L.H. An innovative method for landslide susceptibility mapping supported by fractal theory, GeoDetector, and random forest: A case study in Sichuan Province, SW China. Nat. Hazards 2023, 118, 2543–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.C.; Wang, P.Q.; Su, L.B.; Li, F. Landslide data sample augmentation and landslide susceptibility analysis in Nyingchi City based on the MCMC model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.F.; He, M.J.; Huang, B.; Dong, Q.; Liu, S.Q. Global landslide mapping using Tibetan plateau landslide dataset and improved YOLOX. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Download Address | Access Date |

|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-1 and its precise orbit data | https://asf.alaska.edu/ | 11 July 2024 |

| Landsat 8 imagery | https://www.usgs.gov/ | 11 July 2024 |

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | https://envi.geoscene.cn/; https://geol.ckcest.cn/ | 15 November 2024 |

| Fault data of Gansu Province | https://geolckcest.cn/ | 15 November 2024 |

| Lithology data of Gansu Province | https://www.resdc.cn/ | 9 December 2024 |

| Geological disaster investigation data of Jingchuan County | https://zrzy.pingliang.gov.cn/ | 9 December 2024 |

| Feature Object | NDVI | Gradient | Layer 8 | GLCM Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold range | [0.1, 0.6] | [50°, 80°] | [430, 490] | [125, 129] |

| Elevation | SPI | STI | TWI | Land Use | Lithology | NDVI | Distance from Road | Distance from River | Distance from Fault | Slope Aspect | PRC | Gradient | PLC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation | 1 | 0.056 | 0.162 | 0.067 | 0.213 | −0.205 | −0.139 | 0.205 | 0.102 | −0.428 | −0.165 | −0.256 | −0.054 | 0.364 |

| SPI | 0.056 | 1 | 0.769 | 0.052 | 0.157 | 0.224 | 0.185 | −0.238 | −0.185 | −0.285 | −0.119 | −0.248 | −0.294 | 0.106 |

| STI | 0.162 | 0.769 | 1 | −0.128 | 0.208 | −0.391 | 0.084 | −0.162 | 0.328 | −0.542 | −0.235 | −0.558 | 0.208 | 0.381 |

| TWI | 0.067 | 0.052 | −0.128 | 1 | −0.153 | −0.264 | 0.108 | −0.207 | −0.127 | 0.024 | 0.132 | 0.056 | 0.194 | −0.320 |

| Land use | 0.213 | 0.157 | 0.208 | −0.153 | 1 | −0.125 | 0.097 | 0.105 | −0.254 | −0.308 | 0.075 | −0.248 | 0.380 | 0.092 |

| Lithology | −0.205 | 0.224 | −0.391 | −0.264 | −0.125 | 1 | −0.126 | 0.179 | 0.105 | 0.485 | 0.246 | −0.118 | −0.264 | −0.076 |

| NDVI | −0.139 | 0.185 | 0.084 | 0.108 | 0.097 | −0.126 | 1 | 0.215 | −0.304 | −0.125 | 0.246 | −0.184 | 0.108 | −0.338 |

| Distance from road | 0.205 | −0.238 | −0.162 | −0.207 | 0.105 | 0.179 | 0.215 | 1 | −0.124 | 0.207 | 0.024 | −0.009 | 0.237 | −0.122 |

| Distance from river | 0.102 | −0.185 | 0.328 | −0.127 | −0.254 | 0.105 | −0.304 | −0.124 | 1 | 0.217 | 0.136 | −0.213 | 0.109 | 0.284 |

| Distance from fault | −0.428 | −0.285 | −0.542 | 0.024 | −0.308 | 0.485 | −0.125 | 0.207 | 0.217 | 1 | 0.217 | 0.624 | −0.418 | 0.133 |

| Slope aspect | −0.165 | −0.119 | −0.235 | 0.132 | 0.075 | 0.246 | 0.246 | 0.024 | 0.136 | 0.217 | 1 | 0.048 | −0.214 | 0.178 |

| PRC | −0.256 | −0.248 | −0.558 | 0.056 | −0.248 | −0.118 | −0.184 | −0.009 | −0.213 | 0.624 | 0.048 | 1 | −0.178 | −0.432 |

| Gradient | −0.054 | −0.294 | 0.208 | 0.194 | 0.380 | −0.264 | 0.108 | 0.237 | 0.109 | −0.418 | −0.214 | −0.178 | 1 | 0.046 |

| PLC | 0.364 | 0.106 | 0.381 | −0.320 | 0.092 | −0.076 | −0.338 | −0.122 | 0.284 | 0.133 | 0.178 | −0.432 | 0.046 | 1 |

| Hazard Factor | Classification | |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Elevation | 916–1054 m, 1054–1141 m, 1141–1222 m, 1222–1303 m, 1303–1463 m. |

| Gradient | 0–5.241519704°, 5.241519704–11.35662602°, 11.35662602–17.47173235°, 17.47173235–24.02363197°, 24.02363197–55.69114685°. | |

| Distance from road | 0–0.003018867 km, 0.003018867–0.007003772 km, 0.007003772–0.011109431 km, 0.011109431–0.017026411 km, 0.017026411–0.030792445 km. | |

| Distance from river | 0–0.016142896 km, 0.016142896–0.035069049 km, 0.035069049–0.057335112 km, 0.057335112–0.087394297 km, 0.087394297–0.141946152 km. | |

| SPI | −13.81551075–−6.94360159, −6.94360159–−2.231435308, −2.231435308–−0.16986256, −0.16986256–2.382560842, 2.382560842–11.21787262. | |

| TWI | −6907.754882813–949.229515165, 949.229515165–2731.225976562, 2731.225976562–5080.22131204, 5080.22131204–8887.213752298, 8887.213752298–13,747.204101563. | |

| NDVI | 0.043099999–0.508318836, 0.508318836–0.654637664, 0.654637664–0.755935314, 0.755935314–0.842225904, 0.842225904–0.999800026. | |

| PLC | −2.428134441–−0.32080935, −0.32080935–−0.10004196, −0.10004196–0.060516142, 0.060516142–0.281283533, 0.281283533–2.689655066. | |

| Qualitative | Slope aspect | Plane, North, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, Southwest, West, Northwest. |

| Lithology | Newly accumulated soil, Loessal soil, Dark loessal soil. | |

| Land use | Arable land, Forest, Grassland, Shrub land, Wetland, Water body, Artificial surface. | |

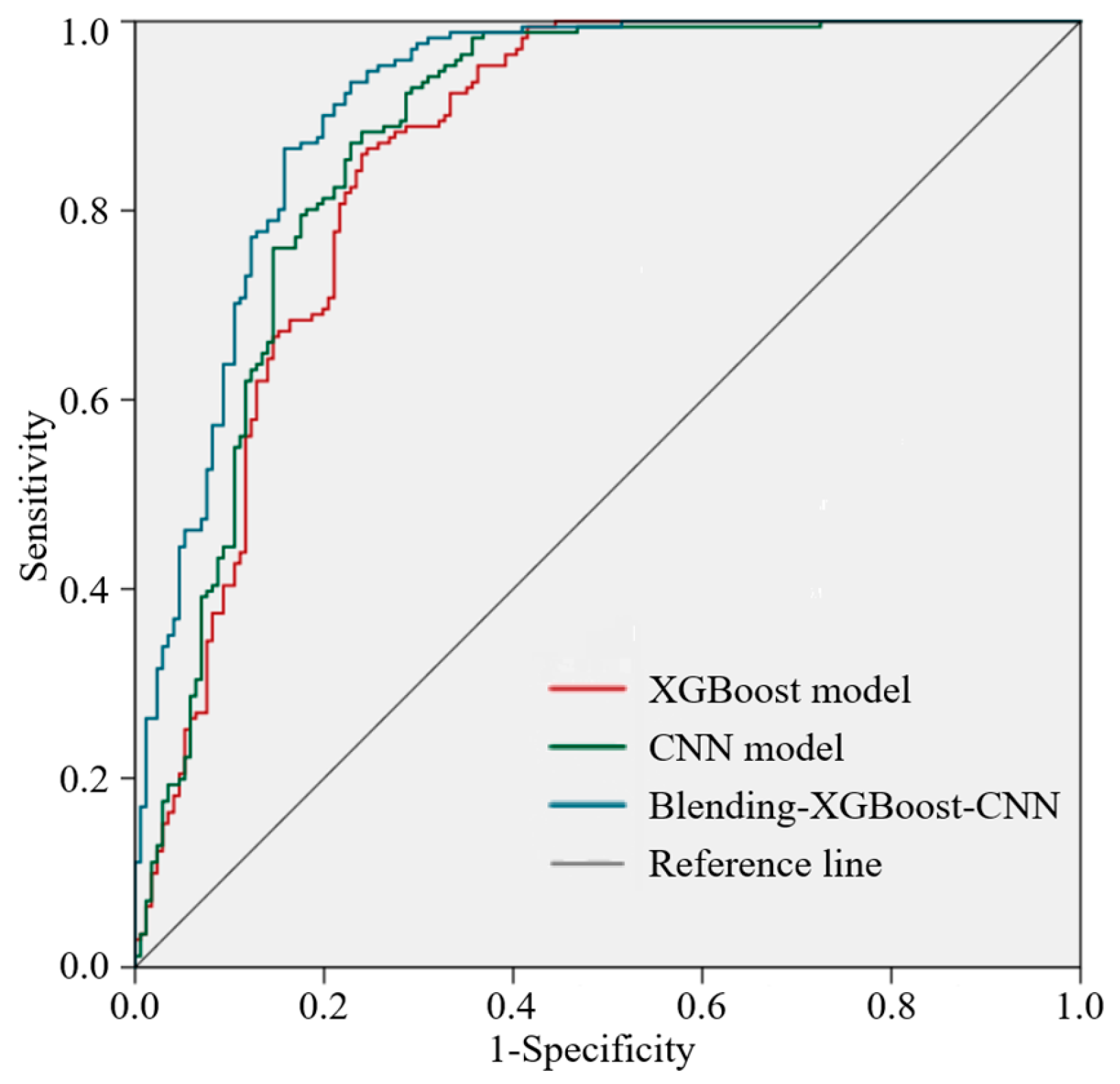

| Model | AUC | Standard Error | Asymptotic Significance | Approaching the 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Limit | ||||

| XGBoost model | 0.882 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.814 | 0.898 |

| CNN model | 0.900 | 0.017 | 0.000 | 0.862 | 0.941 |

| Blending-XGBoost-CNN model | 0.912 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.883 | 0.947 |

| Hazard Factor | Elevation | NDVI | TWI | Slope Aspect | Gradient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q | 0.451 | 0.604 | 0.204 | 0.432 | 0.742 |

| Hazard factor | PLC | Distance from river | Distance from road | Lithology | Land use |

| q | 0.079 | 0.349 | 0.045 | 0.198 | 0.384 |

| Elevation | NDVI | TWI | Slope Aspect | Gradient | PLC | Distance from River | Distance from Road | Lithology | Land Use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elevation | 0.416 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| NDVI | 0.120 | 0.894 | NE | BE | NE | BE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| TWI | 0.894 | 0.317 | 0.894 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE | BE | NE |

| Slope aspect | 0.489 | 0.029 | 0.916 | 0.415 | NE | BE | BE | NE | NE | NE |

| Gradient | 0.859 | 0.347 | 0.247 | 0.154 | 0.129 | NE | NE | NE | NE | NE |

| PLC | 0.132 | 0.095 | 0.379 | 0.844 | 0.451 | 0.045 | BE | BE | BE | NE |

| Distance from river | 0.951 | 0.484 | 0.294 | 0.626 | 0.152 | 0.562 | 0.207 | NE | BE | NE |

| Distance from road | 0.452 | 0.182 | 0.337 | 0.052 | 0.485 | 0.879 | 0.351 | 0.305 | BE | NE |

| Lithology | 0.589 | 0.308 | 0.647 | 0.589 | 0.872 | 0.156 | 0.509 | 0.429 | 0.117 | BE |

| Land use | 0.784 | 0.546 | 0.653 | 0.297 | 0.546 | 0.451 | 0.672 | 0.604 | 0.694 | 0.462 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, B.; Yin, C.; Gao, F.; Song, X.; Li, M. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Remote Sensing Interpretation and a Blending-XGBoost-CNN Model. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211969

Ma B, Yin C, Gao F, Song X, Li M. Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Remote Sensing Interpretation and a Blending-XGBoost-CNN Model. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211969

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Baocheng, Chao Yin, Feng Gao, Xilong Song, and Mingyang Li. 2025. "Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Remote Sensing Interpretation and a Blending-XGBoost-CNN Model" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211969

APA StyleMa, B., Yin, C., Gao, F., Song, X., & Li, M. (2025). Landslide Susceptibility Mapping Using Remote Sensing Interpretation and a Blending-XGBoost-CNN Model. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11969. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211969