Effects of Grain Size, Density, and Contact Angle on the Soil–Water Characteristic Curve of Coarse Granular Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Lvca–PMM Model

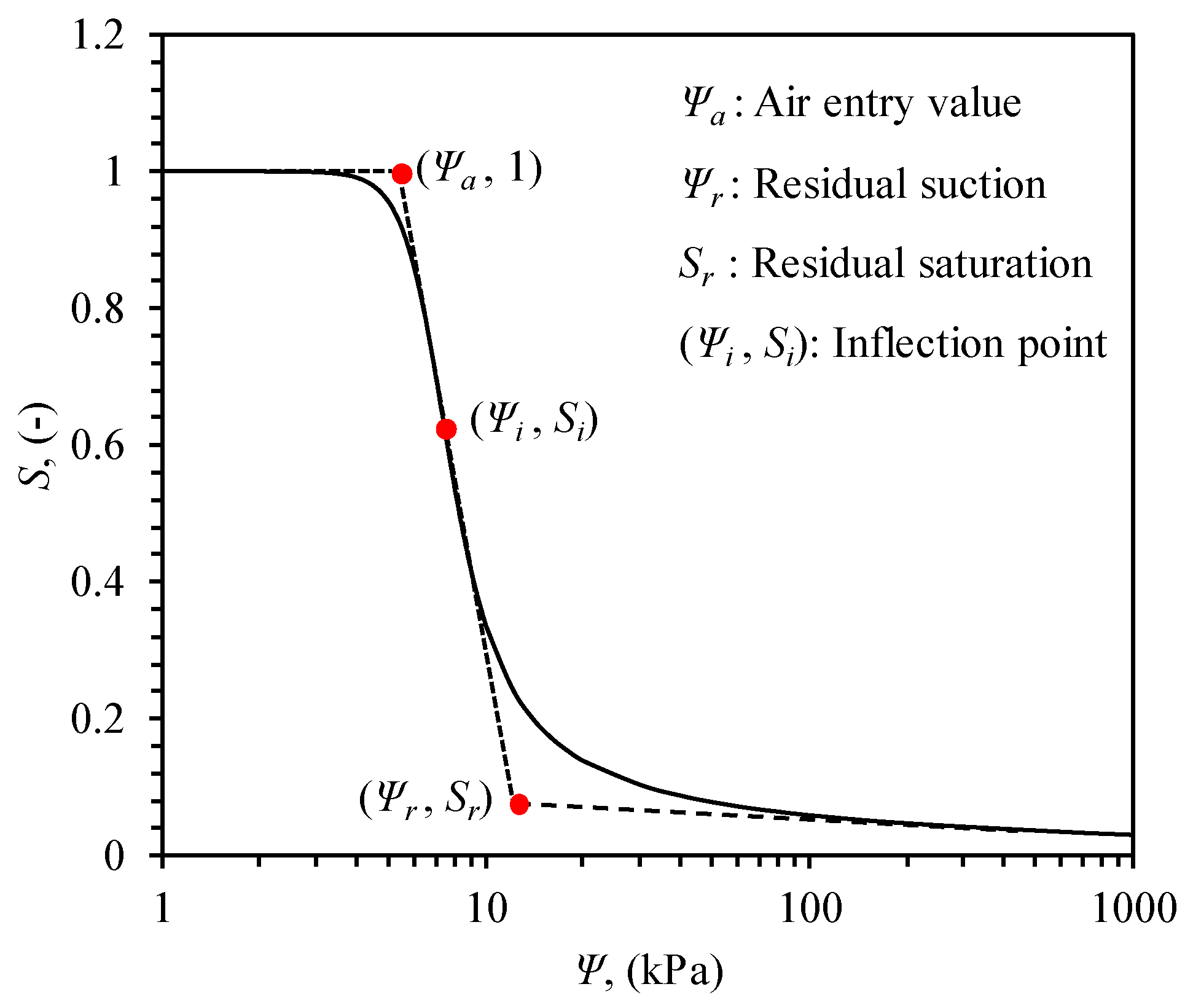

2.2. SWCC Variables

2.3. Numerical Setup

3. Results and Discussion

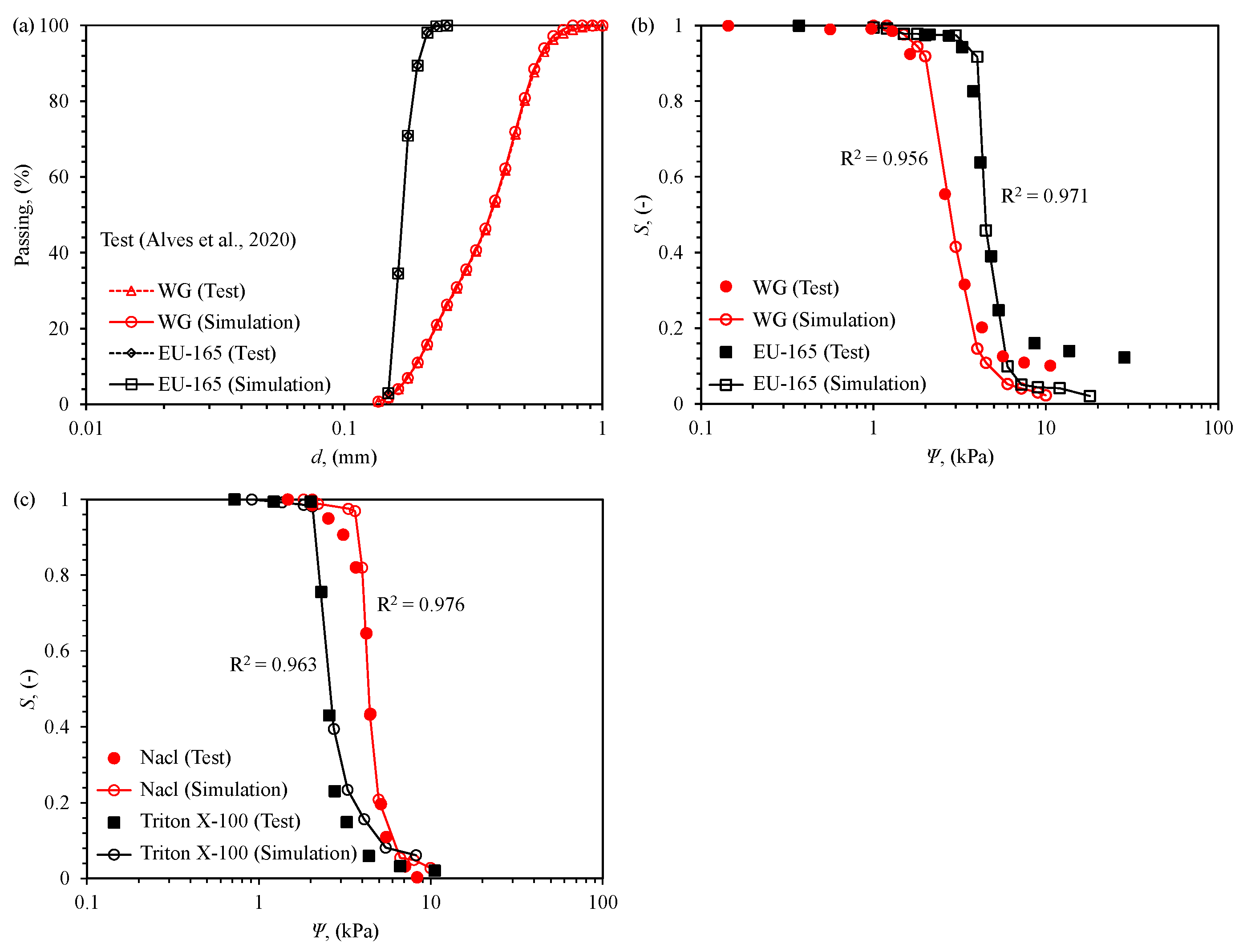

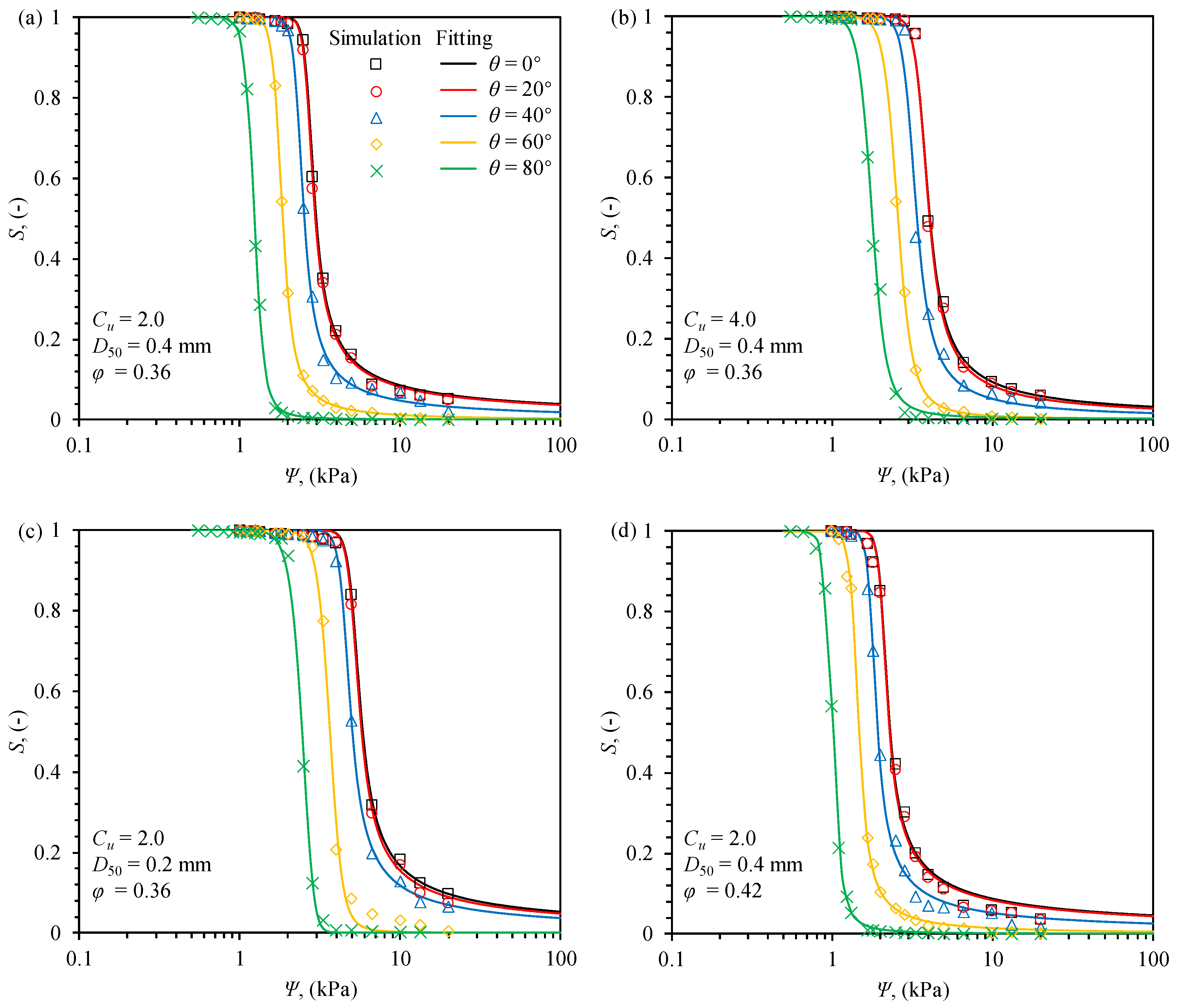

3.1. Soil–Water Characteristic Curves

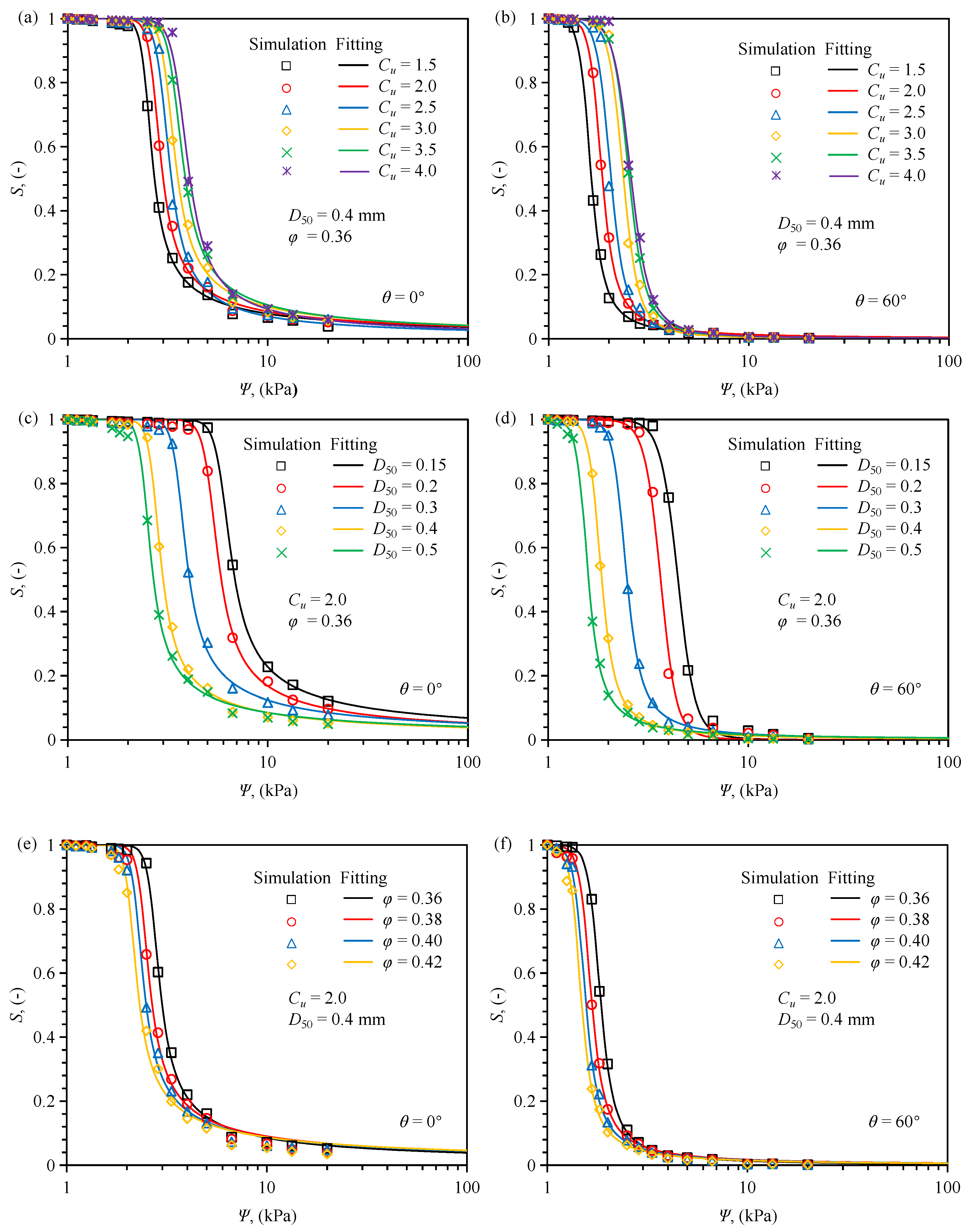

3.2. The Effect of on SWCC

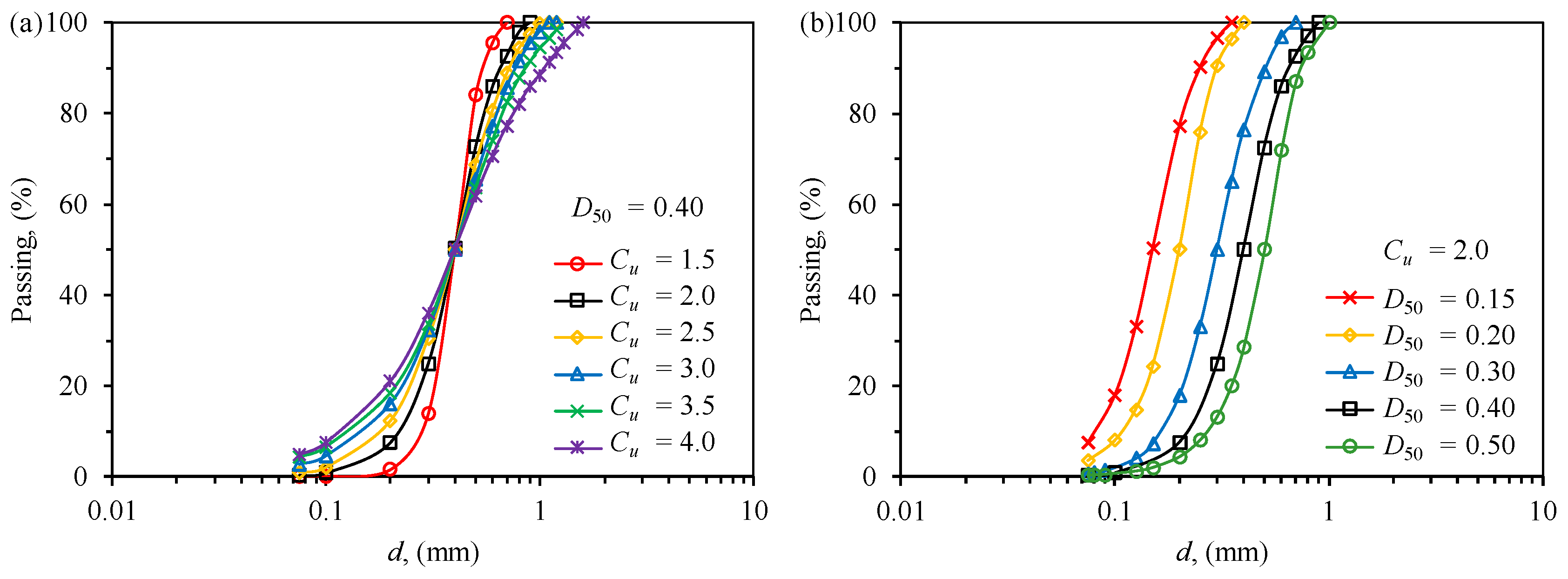

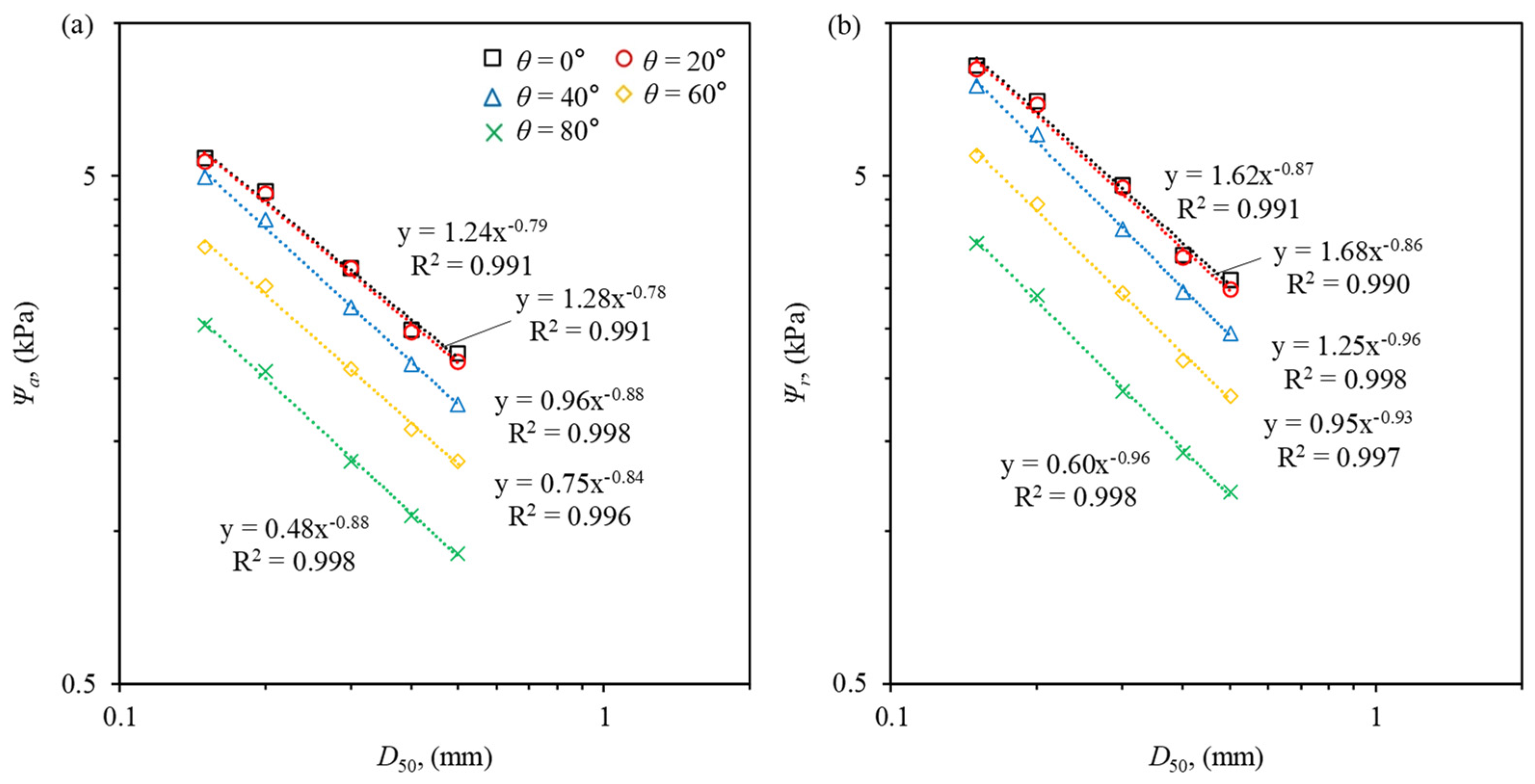

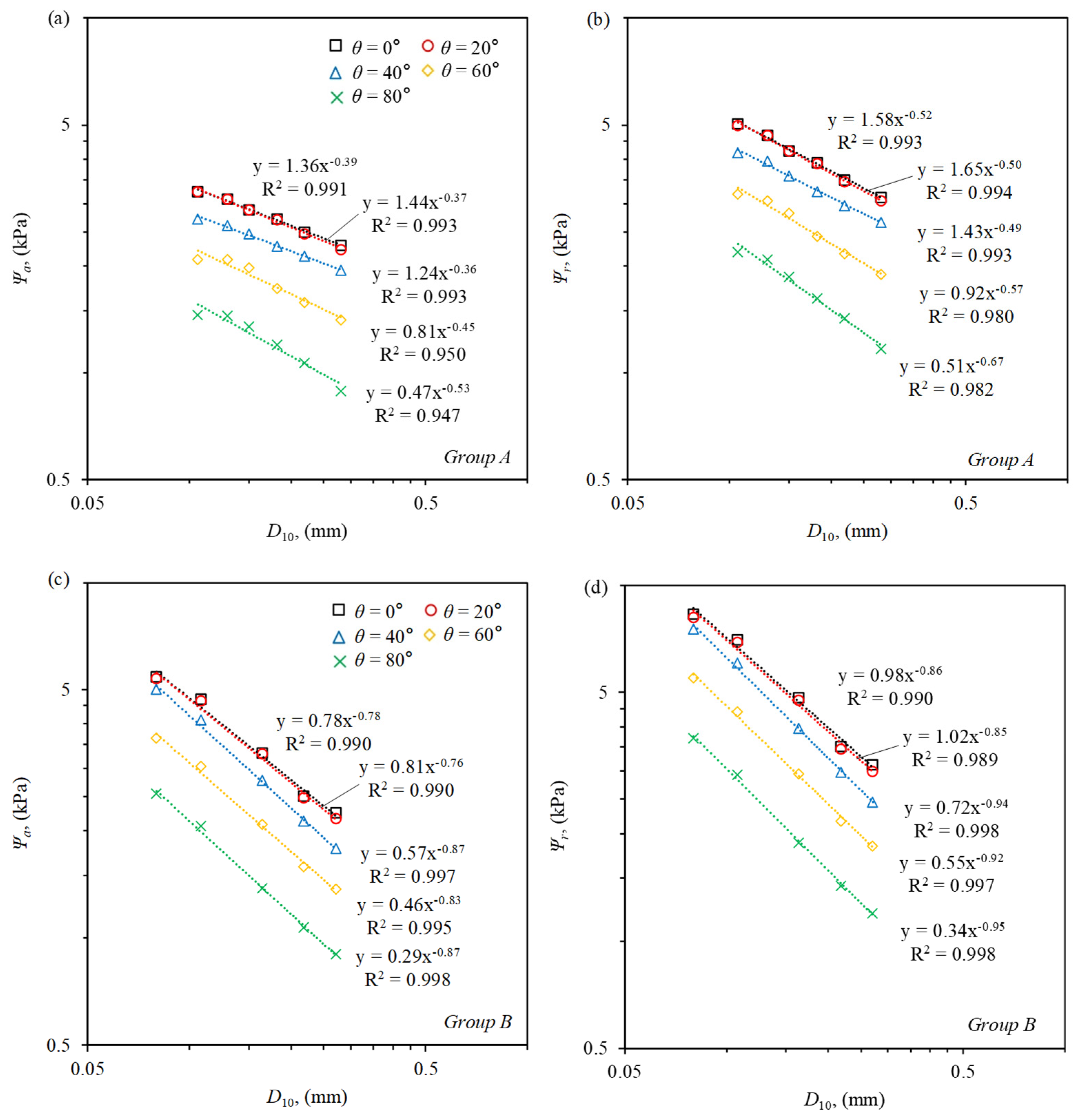

3.3. The Effect of Grain Size on SWCC

3.4. The Effect of on SWCC

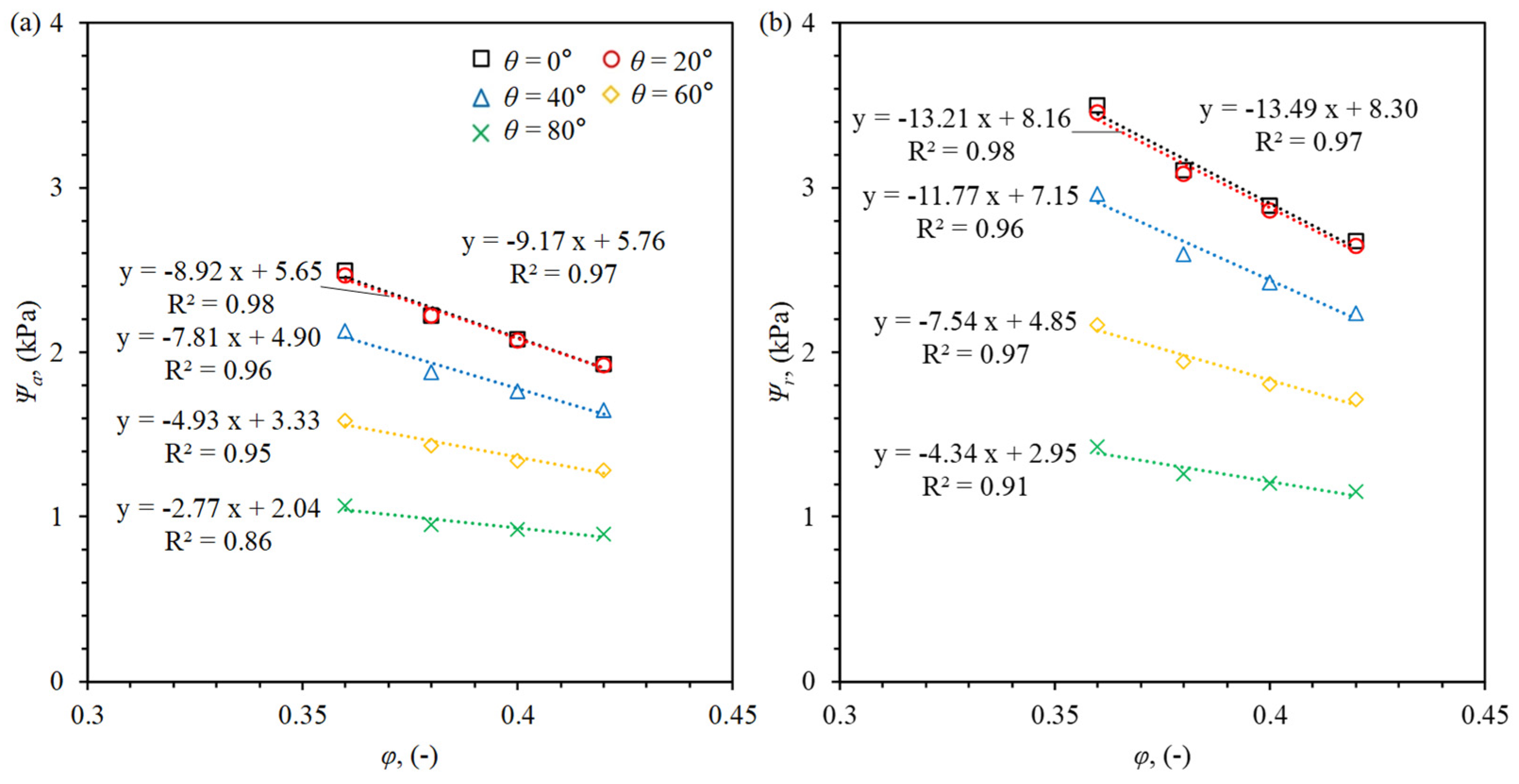

3.5. The Effect of on SWCC

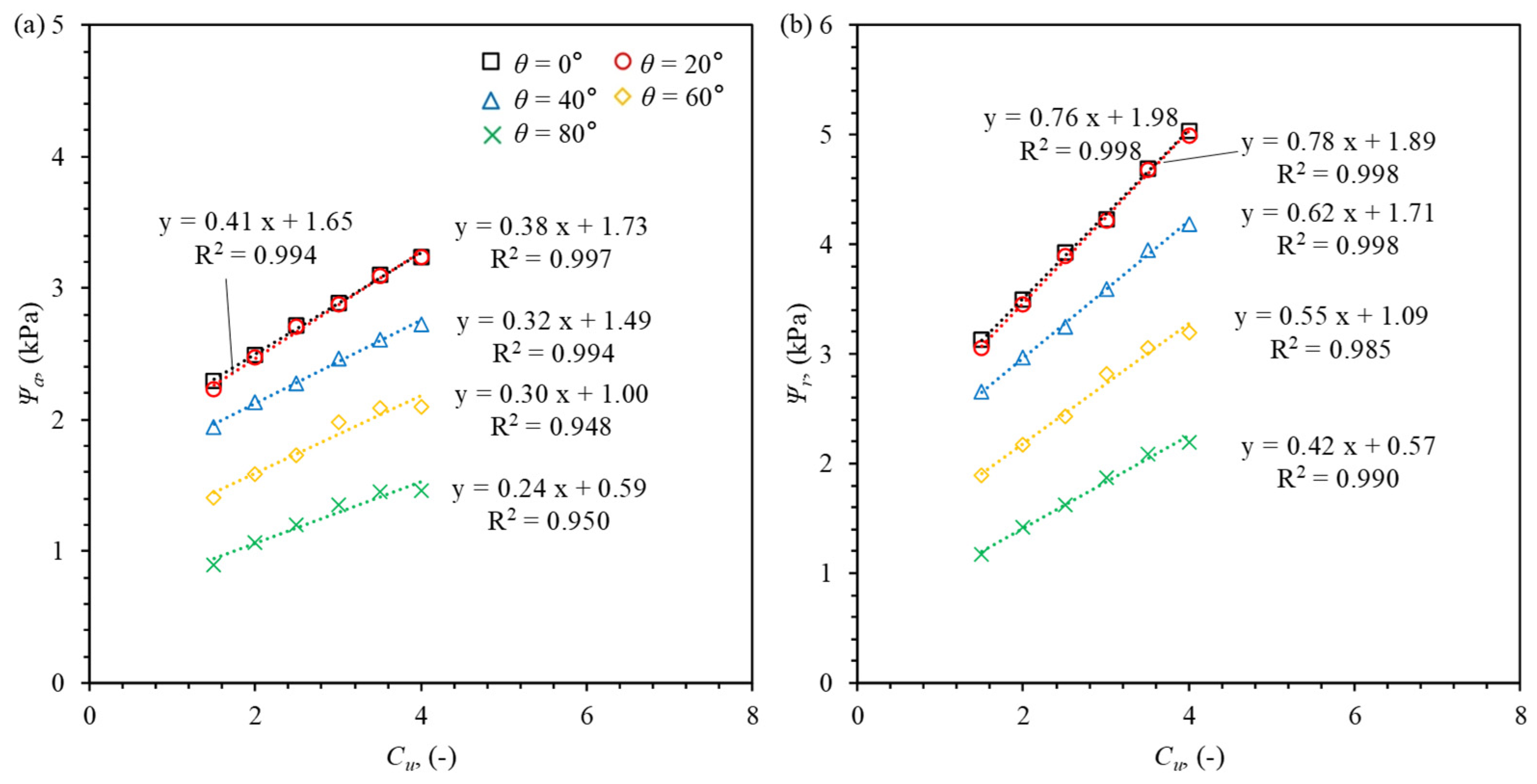

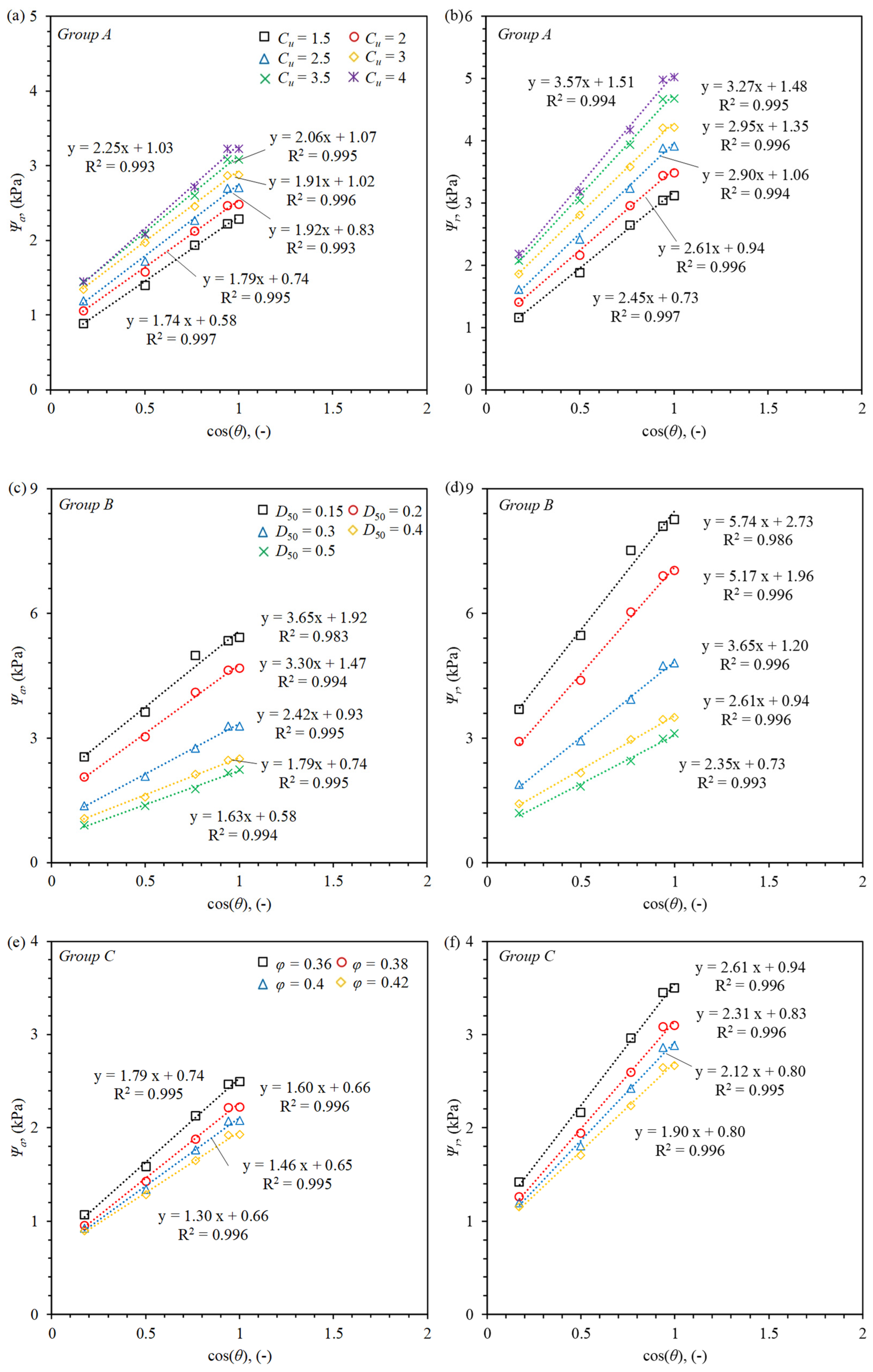

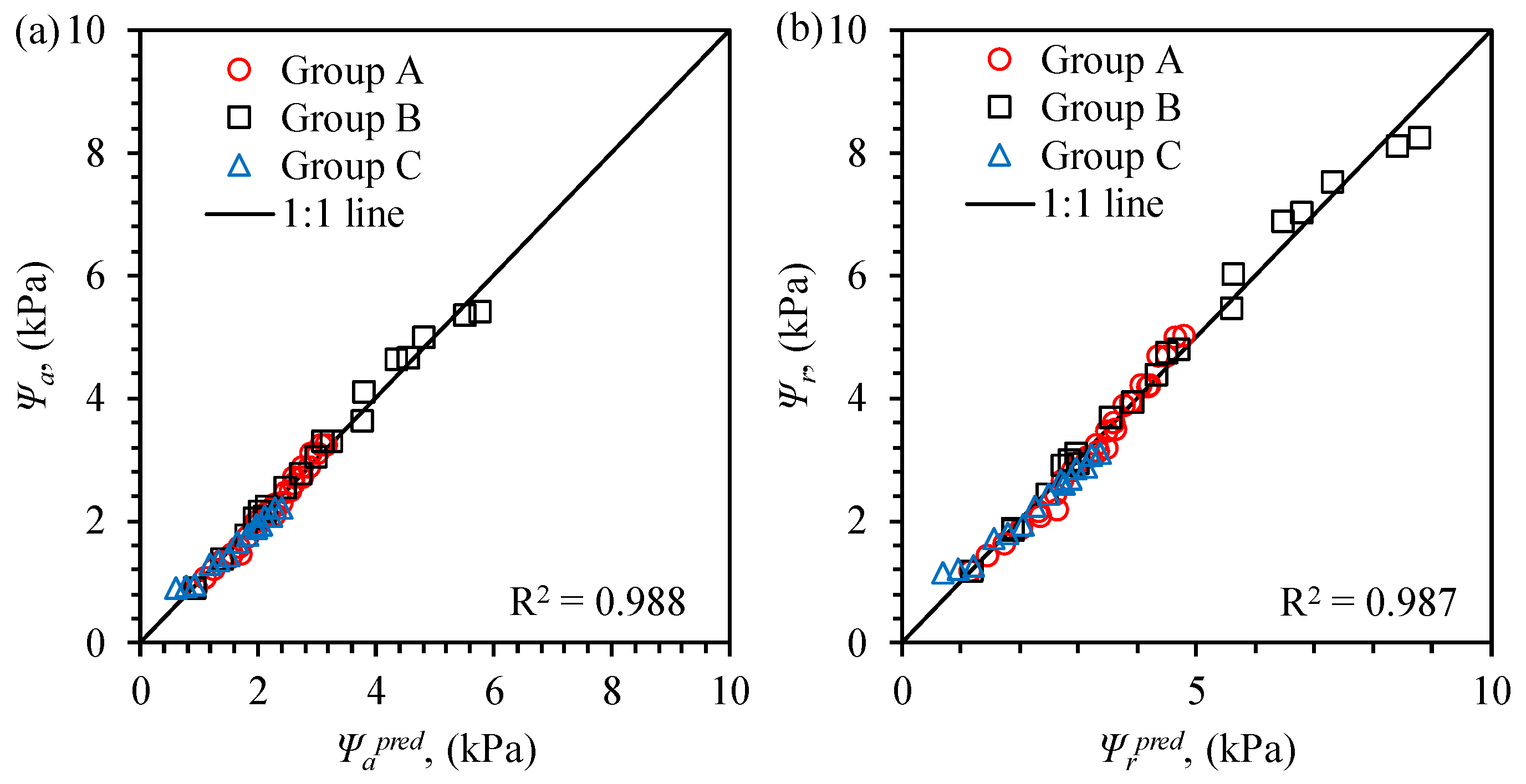

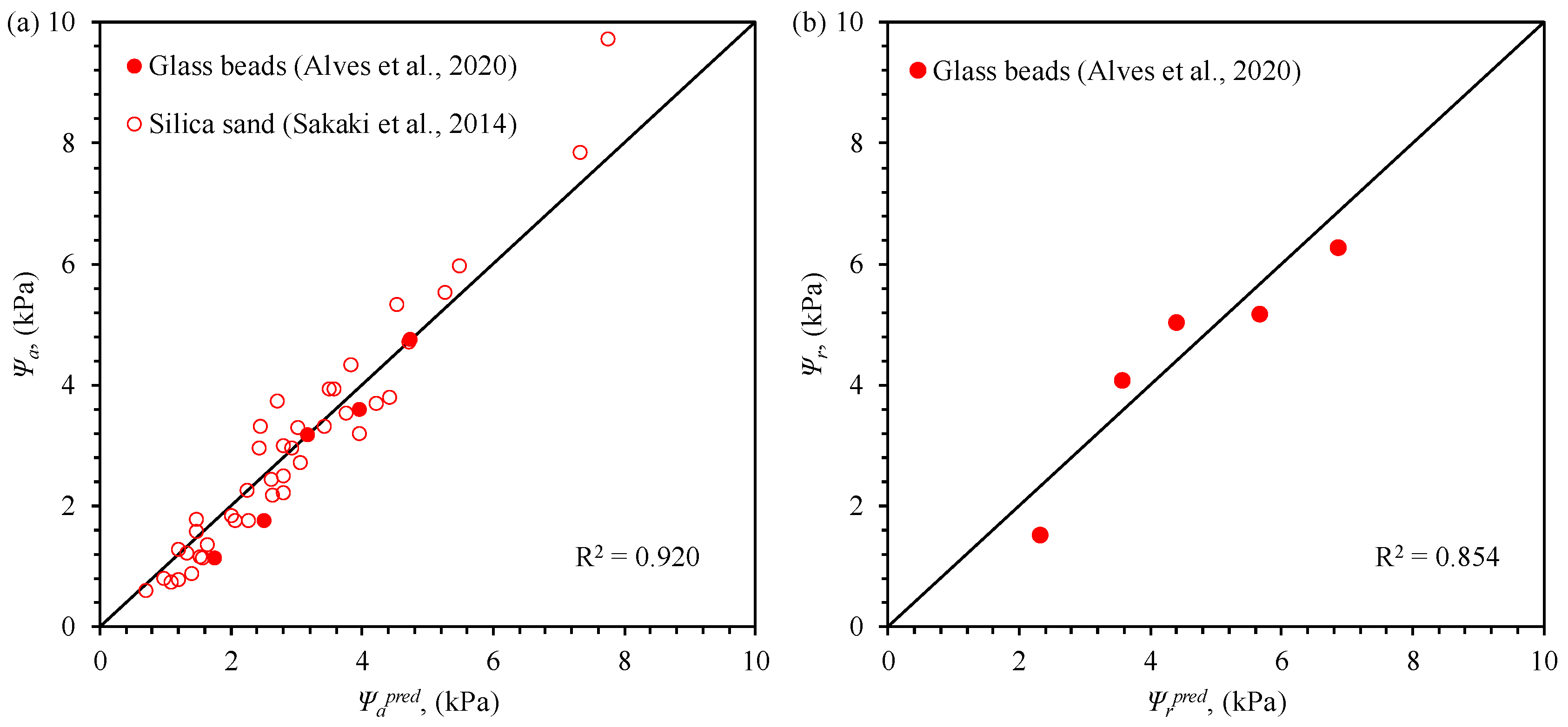

3.6. Curve Fitting

4. Conclusions and Limitations

- The results demonstrate that smaller , larger , higher , and increased result in a leftward shift of the SWCC curve, leading to lower and . These results align closely with experimental observations, which validate the predictive capability of the Lvca-PMM model.

- Linear relationships were identified between SWCC variables ( and ) and factors such as , , and . In contrast, a power-law relationship was observed between SWCC variables and , demonstrating the nonlinear effects of grain size distribution on water retention behavior, particularly for finer particle sizes.

- Empirical equations developed in this study provide practical tools for estimating and based on soil properties. These equations demonstrate that the combined effects of grain size distribution, density, and contact angle must be considered to accurately predict SWCC behavior.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Y.; Sun, D. Soil-water retention behavior of compacted soil with different densities over a wide suction range and its prediction. Comput. Geotech. 2017, 91, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaya, C.; Sreedeep, S. Critical Review on the Parameters Influencing Soil-Water Characteristic Curve. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2012, 138, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Rahardjo, H. Estimation of permeability function from the soil–water characteristic curve. Eng. Geol. 2015, 199, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Dai, F.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, W. Analysis of Soil–Water Characteristic Curve and Microstructure of Undisturbed Loess. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Bao, Z.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Peng, P.; Chen, X. Investigation of the Water-Retention Characteristics and Mechanical Behavior of Fibre-Reinforced Unsaturated Sand. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, H.; Indrawan, I.; Leong, E.; Yong, W. Effects of coarse-grained material on hydraulic properties and shear strength of top soil. Eng. Geol. 2008, 101, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, D.G. State of practice for use of the soil-water characteristic curve (SWCC) in geotechnical engineering. Can. Geotech. J. 2019, 56, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillers, W.S.; Fredlund, D.G. Statistical assessment of soil-water characteristic curve models for geotechnical engineering. Can. Geotech. J. 2001, 38, 1297–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, N.M.; Khoshghalb, A.; Khalili, N. Pore-scale simulation of soil water retention curves using DEM-derived pore networks. Comput. Geotech. 2026, 189, 107625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, A.; Khoshghalb, A.; Khalili, N. Evolution of isochoric water retention curve with void ratio. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 122, 103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, A.; Khoshghalb, A.; Khalili, N. Can degree of saturation decrease during constant suction compression of an unsaturated soil? Comput. Geotech. 2019, 106, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, A.Y.; Khoshghalb, A.; Khalili, N. Hysteretic Model for the Evolution of Water Retention Curve with Void Ratio. J. Eng. Mech. 2017, 143, 04017030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallage, C.P.K.; Uchimura, T. Effects of Dry Density and Grain Size Distribution on Soil-Water Characteristic Curves of Sandy Soils. Soils Found. 2010, 50, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, T.; Komatsu, M.; Takahashi, M. Rules-of-Thumb for Predicting Air-Entry Value of Disturbed Sands from Particle Size. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustohal, P.; Stauffer, F.; Dracos, T. Measurement and modeling of hydraulic characteristics of unsaturated porous media with mixed wettability. J. Contam. Hydrol. 1998, 33, 5–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishakoglu, A.; Baytas, A.F. The influence of contact angle on capillary pressure–saturation relations in a porous medium including various liquids. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2005, 43, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Valocchi, A.J.; Christensen, K.T. Lattice Boltzmann simulations of liquid CO2 displacing water in a 2D heterogeneous micromodel at reservoir pressure conditions. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2018, 212, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavuluri, S.; Maes, J.; Doster, F. Spontaneous imbibition in a microchannel: Analytical solution and assessment of volume of fluid formulations. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2018, 22, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilpert, M.; Miller, C.T. Pore-morphology-based simulation of drainage in totally wetting porous media. Adv. Water Resour. 2001, 24, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, A.; Li, J.; Feng, S. Reproducing micro X-ray computed tomography (microXCT) observations of air–water distribution in porous media using revised pore-morphology method. Can. Geotech. J. 2020, 57, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, A.; Shen, S.-L.; Li, J. Modeling drainage in porous media considering locally variable contact angle based on pore morphology method. J. Hydrol. 2022, 612, 128157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, H.; Tölke, J.; Schulz, V.P.; Krafczyk, M.; Roth, K. Comparison of a Lattice-Boltzmann Model, a Full-Morphology Model, and a Pore Network Model for Determining Capillary Pressure–Saturation Relationships. Vadose Zone J. 2005, 4, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; MacMinn, C.W.; Primkulov, B.K.; Chen, Y.; Valocchi, A.J.; Zhao, J.; Kang, Q.; Bruning, K.; McClure, J.E.; Miller, C.T.; et al. Comprehensive comparison of pore-scale models for multiphase flow in porous media. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 13799–13806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Y.; Sungkorn, R.; Toelke, J. Identifying the representative flow unit for capillary dominated two-phase flow in porous media using morphology-based pore-scale modeling. Adv. Water Resour. 2016, 95, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, V.P.; Becker, J.; Wiegmann, A.; Mukherjee, P.P.; Wang, C.-Y. Modeling of Two-Phase Behavior in the Gas Diffusion Medium of PEFCs via Full Morphology Approach. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, B419–B426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Knüfing, L.; Arns, C.; Sakellariou, A.; Senden, T.; Sheppard, A.; Sok, R.; Limaye, A.; Pinczewski, W.; Knackstedt, M. Three-dimensional imaging of multiphase flow in porous media. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2004, 339, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.D.; Gitirana, G., Jr.; Vanapalli, S.K. Advances in the modeling of the soil–water characteristic curve using pore-scale analysis. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 127, 103766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sghaier, N.; Prat, M.; Ben Nasrallah, S. On the influence of sodium chloride concentration on equilibrium contact angle. Chem. Eng. J. 2006, 122, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagunduz, A.; Pennell, K.D.; Young, M.H. Influence of a Nonionic Surfactant on the Water Retention Properties of Unsaturated Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 1392–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, A.; Sun, K.; Shen, S.-L. Discrete element modelling of the macro/micro-mechanical behaviour of unsaturated soil in direct shear tests including wetting process. Powder Technol. 2023, 415, 118125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, A.; Shen, S.-L.; Li, J.; Arulrajah, A. Modelling unsaturated soil-structure interfacial behavior by using DEM. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 137, 118125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, N.; Gautam, S.; Farhan, N.M.; Tafreshi, H.V.; Pourdeyhimi, B. Accuracy of the Pore Morphology Method in Modeling Fluid Saturation in 3D Fibrous Domains. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 18147–18159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Bhatta, N.; Kumar, A.; Tafreshi, H.V.; Pourdeyhimi, B. Matlab implementation of pore morphology method for modeling liquid residue in porous media with heterogeneous wettabilities. Powder Technol. 2025, 452, 120509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, D.; Xing, A. Equations for the soil-water characteristic curve. Can. Geotech. J. 1994, 31, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Rahardjo, H.; Satyanaga, A. Effects of residual suction and residual water content on the estimation of permeability function. Geoderma 2017, 303, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, D.; Zhou, A.; Li, J. Predicting Shear Strength of Unsaturated Soils over Wide Suction Range. Int. J. Geomech. 2020, 20, 04019175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T50145-2007; Standard for Engineering Classification of Soil. China Planning Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Benson, C.H.; Chiang, I.; Chalermyanont, T.; Sawangsuriya, A. Estimating van Genuchten Parameters α and n for Clean Sands from Particle Size Distribution Data. In Proceedings of the Geo-Congress 2014, Atlanta, GA, USA, 23–26 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.E.; Gillham, R.W. Effects of solute concentration–dependent surface tension on unsaturated flow: Laboratory sand column experiments. Water Resour. Res. 1999, 35, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Chen, R.-P.; Kang, X.; Lei, H. Effects of particle morphology on pore structure and SWRC of granular soils. Géotech. Lett. 2023, 13, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.-F.; Pinzón, G.; Wiebicke, M.; Andò, E.; Kruyt, N.P.; Viggiani, G. Evolution of fabric anisotropy of granular soils: X-ray tomography measurements and theoretical modelling. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 133, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viggiani, G.; Andò, E.; Takano, D.; Santamarina, J. Laboratory X-ray Tomography: A Valuable Experimental Tool for Revealing Processes in Soils. Geotech. Test. J. 2015, 38, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakharian, K.; Kaviani-Hamedani, F.; Sooraki, A.; Amindehghan, M.; Lashkari, A. Continuous bidirectional shear moduli monitoring and micro X-ray CT to evaluate fabric evolution under different stress paths. Granul. Matter 2023, 25, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Groups | (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4 | 0.4 | 0.36 |

| B | 2 | 0.15, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 | 0.36 |

| C | 2 | 0.4 | 0.36, 0.38, 0.4, 0.42 |

| Material Type | (mm) | (°) | (kPa) | (kPa) | (kPa) | (kPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass beads † | EU-165 Nacl | 0.165 | 1.06 | 0.354 | 56.5 | 3.172 | 3.178 | 5.032 | 4.395 |

| EU-165 X-100 | 0.165 | 1.06 | 0.354 | 12.6 | 4.743 | 4.736 | 6.263 | 6.865 | |

| EU-165 | 0.165 | 1.06 | 0.354 | 39.8 | 3.592 | 3.973 | 5.182 | 5.655 | |

| WG | 0.368 | 1.92 | 0.334 | 39.8 | 1.755 | 2.505 | 4.080 | 3.561 | |

| EU-412 | 0.412 | 1.06 | 0.368 | 39.8 | 1.127 | 1.755 | 1.519 | 2.306 | |

| Group A ‡ uniform crushed silica | A1 | 1.51 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.589 | 0.716 | - | - |

| A2 | 0.95 | 1.6 | 0.41 | 0 | 0.785 | 0.994 | - | - | |

| A3 | 0.72 | 1.4 | 0.41 | 0 | 1.275 | 1.212 | - | - | |

| A4 | 0.56 | 1.4 | 0.41 | 0 | 1.570 | 1.491 | - | - | |

| A5 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.43 | 0 | 1.766 | 1.474 | - | - | |

| A6 | 0.31 | 2 | 0.43 | 0 | 2.943 | 2.449 | - | - | |

| A7 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 0.42 | 0 | 3.924 | 3.502 | - | - | |

| Group B ‡ uniform round silica | B1 | 1.04 | 1.2 | 0.32 | 0 | 0.765 | 1.205 | - | - |

| B2 | 0.75 | 1.2 | 0.32 | 0 | 1.128 | 1.578 | - | - | |

| B3 | 0.52 | 1.2 | 0.33 | 0 | 1.746 | 2.068 | - | - | |

| B4 | 0.36 | 1.2 | 0.33 | 0 | 2.207 | 2.801 | - | - | |

| B5 | 0.27 | 1.2 | 0.34 | 0 | 3.306 | 3.437 | - | - | |

| B1′ | 1.08 | 1.2 | 0.34 | 0 | 0.726 | 1.095 | - | - | |

| B2′ | 0.75 | 1.2 | 0.33 | 0 | 1.148 | 1.529 | - | - | |

| B3′ | 0.53 | 1.1 | 0.33 | 0 | 1.825 | 2.012 | - | - | |

| B4′ | 0.36 | 1.2 | 0.33 | 0 | 2.482 | 2.801 | - | - | |

| Group C ‡ uniform med-fine silica | C1 | 0.28 | 1.7 | 0.32 | 0 | 3.532 | 3.761 | - | - |

| C2 | 0.12 | 1.7 | 0.33 | 0 | 7.848 | 7.344 | - | - | |

| C3 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.36 | 0 | 9.722 | 7.759 | - | - | |

| Group D ‡ less-uniform crushed silica | D1 | 0.45 | 2 | 0.37 | 0 | 2.256 | 2.251 | - | - |

| D2 | 0.41 | 2.9 | 0.38 | 0 | 2.433 | 2.617 | - | - | |

| D3 | 0.15 | 1.9 | 0.37 | 0 | 5.964 | 5.504 | - | - | |

| D4 | 0.19 | 2.2 | 0.38 | 0 | 5.317 | 4.544 | - | - | |

| D5 | 0.42 | 5.4 | 0.31 | 0 | 4.326 | 3.849 | - | - | |

| D6 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 0.4 | 0 | 3.296 | 3.023 | - | - | |

| D7 | 0.68 | 1.7 | 0.41 | 0 | 1.207 | 1.329 | - | - | |

| Group E ‡ less-uniform round silica | E1 | 0.85 | 1.4 | 0.33 | 0 | 0.863 | 1.411 | - | - |

| E2 | 0.75 | 1.6 | 0.32 | 0 | 1.354 | 1.650 | - | - | |

| E3 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 0.29 | 0 | 1.756 | 2.269 | - | - | |

| E4 | 0.52 | 2.2 | 0.28 | 0 | 2.178 | 2.645 | - | - | |

| E5 | 0.43 | 4.2 | 0.24 | 0 | 3.188 | 3.977 | - | - | |

| E6 | 0.36 | 3.6 | 0.26 | 0 | 3.679 | 4.226 | - | - | |

| E7 | 0.31 | 3.2 | 0.28 | 0 | 3.796 | 4.427 | - | - | |

| E8 | 0.27 | 2.9 | 0.29 | 0 | 4.709 | 4.722 | - | - | |

| E9 | 0.22 | 2.8 | 0.31 | 0 | 5.523 | 5.271 | - | - | |

| Group F ‡ field sands | F1 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 0.44 | 0 | 3.728 | 2.720 | - | - |

| F2 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0 | 3.934 | 3.579 | - | - | |

| F3 | 0.34 | 2.1 | 0.35 | 0 | 2.717 | 3.060 | - | - | |

| F4 | 0.32 | 1.8 | 0.38 | 0 | 2.982 | 2.810 | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Li, R.; Sun, X.; Wang, X. Effects of Grain Size, Density, and Contact Angle on the Soil–Water Characteristic Curve of Coarse Granular Materials. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211910

Liu X, Li R, Sun X, Wang X. Effects of Grain Size, Density, and Contact Angle on the Soil–Water Characteristic Curve of Coarse Granular Materials. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(22):11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211910

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xin, Ruixuan Li, Xi Sun, and Xiaonan Wang. 2025. "Effects of Grain Size, Density, and Contact Angle on the Soil–Water Characteristic Curve of Coarse Granular Materials" Applied Sciences 15, no. 22: 11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211910

APA StyleLiu, X., Li, R., Sun, X., & Wang, X. (2025). Effects of Grain Size, Density, and Contact Angle on the Soil–Water Characteristic Curve of Coarse Granular Materials. Applied Sciences, 15(22), 11910. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152211910