Abstract

Background: This study aimed to examine changes in force, impulse, and kinematic variables in relation to swimming performance during two equal load twelve-week training programs across two annual cycles. Methods: Eight national-level adolescent swimmers participated in two twelve-week training cycles across Year 1 and Year 2. The swimmers underwent performance tests (50 m, 200 m, 400 m), and stroke rate (SR), stroke length (SL), and stroke index (SI) were assessed. A 30 s tethered swimming test was applied to evaluate tethered force (TF) and impulse (IMP) before and after each training cycle. The training load was assessed during the twelve weeks across Year 1 and Year 2. Results: The training load was similar in Year 1 and Year 2 (d = 0.51–0.52, p = 0.09). The performance in 50, 200, and 400 m front crawl tests was improved following the 12-week training period in both years (d = 0.29–0.90, p = 0.01–0.04). The mean TF and maximal TF increased in Year 1 (d = 0.64, p = 0.01), while IMP was decreased in Year 2 (Year 1: +4.3 ± 6.8% vs. Year 2: −6.8 ± 4.5%, d = 1.28, p = 0.01). SR remained unchanged, but SL was increased in the 200 m (d = 0.19–0.41, p = 0.01), and SI improved in both 200 (d = 0.27–0.59, p = 0.01) and 400 m tests (d = 0.23–0.24, p = 0.01). Significant correlations were found in Year 1 between IMP and SR (r = −0.74, 95%CI: −0.08, −0.95, p = 0.01), and between IMP and both SL (r = 0.94, 95%CI: 0.98, 0.68, p = 0.01) and SI in the 400 m test (r = 0.87, 95%CI: 0.97, 0.44, p = 0.01). Conclusions: An equal load twelve-week swimming training period improved performance and kinematic parameters across Year 1 and Year 2. Changes in the tethered swimming force and impulse were observed only in the first year, highlighting the importance of targeted strength interventions for enhancing swimming performance.

1. Introduction

Swimming performance is influenced by multiple factors, including technique, strength, endurance, anthropometrics, and physiological aspects [1]. To achieve this, swim-specific and dry-land strength training have been included in the swimmers’ training schedule [2]. However, the in-water force applied by the swimmer is equally important for optimizing performance [3]. Several studies have focused on the relationship between dry-land strength and swimming performance [4,5]. Recently, it has been reported that there are increases in swimmers’ water force and improvements in 25 m performance time during a training year [6]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated whether the changes in tethered swimming force following a training period are associated with performance adaptations over two training years.

Tethered swimming is usually used as a specific test to determine the produced impulse [7,8,9]. Research findings provide evidence that the maximum and average impulse observed in tethered swimming correlates with performance in short- (50, 100 m [5,9]) and middle-distance tests (200 m [10,11]). Moreover, tethered swimming force and impulse appear to be related to kinematic variables, such as stroke length (SL), stroke rate (SR), and stroke index (SI), particularly in short-distance events, such as the 50 m [12,13]. Nevertheless, there is no evidence whether training-induced changes in specific swimming force will also lead to changes in kinematic characteristics during short- and middle-distance efforts.

Long-term training interventions (6–12 weeks) that integrate dry-land strength exercises, aerobic swimming sets, and high-intensity training within a microcycle have been shown to improve swimming performance across 25, 50, and 400 m tests, increase upper- and lower-body one-repetition maximum strength, and enhance SR and SL [2,14]. Additionally, athletes’ biological maturation may influence performance adaptations. More specifically, during biological maturation, improvements in swimmers’ performance across various distances (e.g., short and middle) may be linked to changes in anthropometric, kinematic, and physiological characteristics [15,16]. Furthermore, in-water propulsive forces may also change during the maturation process [17,18]. However, little is known about how propulsive force and performance change within the same group of swimmers when the training load remains similar across two training periods over two years.

Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine changes in tethered swimming force and kinematic variables during two twelve-week periods, with comparable training loads applied over a two-year period. It was also examined whether changes in in-water force, impulse, and kinematical variables are related to changes in performance time during 50 m, 200 m, and 400 m tests. We hypothesized that tethered force and impulse would improve after a twelve-week swimming training period over two years, and this improvement would be positively related to the swimmers’ performance in both short- and middle-distance swimming.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Eight highly trained national-level swimmers (tier 3 [19]), five males and three females (age: 14.1 ± 1.5 years, age range: 13 to 16 years, body mass: 55.8 ± 8.9 kg, body height: 163.8 ± 10.0 cm), voluntarily participated in this study. The primary parameter for the sample size estimation was the tethered swimming force measured during the tethered swimming test. Previous studies have reported modest improvements in tethered swimming force, typically 5–15%, corresponding to a medium or large effect size depending on the training modality and swimmers’ level [6,9]. The post hoc power analysis was calculated to 0.82, considering the sample size (n = 8), the corresponding lower partial eta squared for the main effect (η2p = 0.07, Cohen’s f: 0.27), the correlation among repeated measures of 0.80, and a nonsphericity correction, ε = 1 [20]. The inclusion criteria required participants to (a) have a minimum of three years of training experience, (b) be free from injury, and (c) abstain from medication use before, during, and after the experimental procedures. The study received approval from the local institutional review board (approval number: 1111/10-04-2019). The swimmers agreed to participate, and their parents or guardians signed a written informed consent form prior to the study’s commencement. The study was conducted following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects.

2.2. Study Design

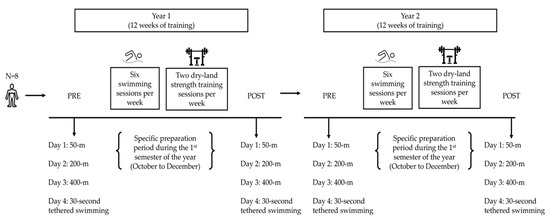

All swimmers participated in twelve weeks of training, applied across two annual training cycles (Year 1 and Year 2), and underwent testing at four distinct time points: before (PRE) and after (POST) a 12-week training intervention within each cycle (Figure 1). The 12-week intervention corresponded to the specific preparation mesocycle conducted during the first semester of each year (October to December). Training content, including distance and intensity, was recorded daily to maintain consistency in training load across both mesocycles. We tried to keep the training load the same in both of the twelve-week mesocycles.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the study design.

Training intensity was categorized into five domains (I to V) based on each swimmer’s speed–lactate curve. Specifically, intensity domains I, II, III, and IV corresponded to estimated blood lactate concentrations of approximately 2, 4, 6, and 8 mmol·L−1, respectively. In contrast, domain V was defined as maximal sprint swimming intensity [21]. For statistical analysis, the total training volume accumulated within each intensity domain over the 12-week training periods was calculated and compared between years.

The training load was quantified using the method proposed by Mujika et al. [21] based on a weighted summation of training intensity across five defined zones. Specifically, the training load was calculated using the following equation:

where I–V represents the training volume (in meters) completed within each corresponding intensity domain. For statistical analysis, the total training load over the 12-week training periods was calculated and compared between years.

Training Load = (I + [II × 2] + [III × 5] + [IV × 8] + [V × 8])/1000

Additionally, throughout both training years, before the swimming training session, swimmers incorporated dry-land strength training twice a week during the 12-week training period, focusing on muscular endurance. This training regimen consisted of 3–4 sets of 15–20 repetitions at 55–60% of one repetition maximum. Each dryland session lasted between 50 and 55 min and comprised five primary exercises: two targeting the upper limbs (bench press, seated pull row) and three for the lower limbs (leg press, leg extension, and squats performed at a 90-degree angle).

Furthermore, all training sessions during the 12-week training period were conducted between 6:00 and 8:00 p.m. in a 50 m outdoor pool (27 °C water temperature; 20–25 °C ambient).

2.3. Experimental Procedures

Before starting the experimental procedures, swimmers’ body mass and height were measured using standardized anthropometric equipment (Seca, Hamburg, Germany). These measures were taken at the beginning of the first year and again at the start of the second year of evaluation. Moreover, swimmers’ biological maturation was estimated at both the beginning and the end of each specific preparation period across both training years [22]. Furthermore, their biological maturity was assessed through a self-evaluation questionnaire by Tanner [23], which was completed with the assistance of the children’s parents and/or legal representatives [24]. The mean value was used for the statistical analysis.

During the week preceding the onset and the week following the completion of the 12-week training period (Figure 1) in both Year 1 and Year 2, all swimmers participated in four testing sessions. On Days 1 to 3, following a standardized 1000 m warm-up (comprising a 400 m front crawl, 4 × 50 m front crawl kicks, 4 × 50 m front crawl drills, and 4 × 50 m front crawls with progressively increasing speed), swimmers performed maximal-effort time trials over a 50, 200, and 400 m front crawl, respectively. Kinematic variables were assessed during all performance tests. SR was determined every 50 m based on the time required to complete three consecutive stroke cycles. SL was calculated as the ratio of swimming speed to SR, and SI was derived as the product of SL and swimming speed for all test distances. Performance was recorded with a hand-held stopwatch (CASIO Co., Ltd., Higashine, Tokyo, Japan).

On Day 4, swimmers performed a 30 s tethered swimming sprint test to assess tethered swimming force (TF). Force measurements were obtained at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz using a calibrated piezoelectric force transducer connected to an analog-to-digital converter (MuscleLab, Ergotest, Sathelle, Norway). The transducer was secured at the swimmer’s hip via a non-elastic cable. A signal was triggered at each upper limb entry into the water to demarcate individual stroke cycles, enabling the analysis of force production and duration of each stroke cycle for the subsequent calculation of impulse (IMP). The maximum tethered force (TFmax) and the minimum tethered force (TFmin) were defined as the highest force and the lowest force averaged over 1 s intervals [25]. The mean TF was used for the statistical analysis. In addition, the fatigue index (FI) was calculated in this test, according to Equation (2), using force data averaged over 1 s intervals [26].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical package SPSS v.23 was used. The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and sphericity was verified with Mauchly’s test. When the assumption of sphericity was not satisfied, the significance of F ratios was adjusted according to Greenhouse–Geisser. A repeated measures analysis of variance with two factors (two time points and two years) was performed for all the measurement variables. The Tukey honest significant difference post hoc test was used to compare means when significant F ratios were found.

The %Δ values were calculated by comparing the post-training period values to the pre-training period values for Year 1 and Year 2 in all testing variables. The Student T-test for paired samples was used to compare the %Δ values between Year 1 and Year 2. Moreover, the Pearson correlation was used to examine relationships between the %Δ values of swimming performance and biomechanical variables with the force variables tested in water. The 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the correlation coefficient were also calculated.

To estimate the magnitude of the main effects and interactions, partial eta squared (η2p) values from the analysis of variance were utilized. The η2p values were interpreted as small (0.01 ≤ η2p < 0.06), medium (0.06 ≤ η2p < 0.14), and large (η2p ≥ 0.14). Effect size values were reported regardless of statistical significance (p > 0.05), as they provide complementary information about the strength of the observed effects. Moreover, the effect size for paired comparisons was calculated with Cohen’s d using the pooled SD as the dominator. The effect size was considered small if the absolute value of Cohen’s d was <0.20, medium if it was between 0.20 and 0.80, and large if it was >0.80 [27]. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical significance was established at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Biological Maturation, Training Distance, and Training Load

The biological maturity of the swimmers, as assessed by the Tanner stage, increased following the 12-week training period in both years (Year 1: PRE, 3.3 ± 1.2 vs. POST, 3.8 ± 0.9, p = 0.01; Year 2: PRE, 4.1 ± 0.6 vs. POST, 4.7 ± 0.3, p = 0.01).

The training distance and training load did not differ between the two years (t = −1.88, p = 0.09 and t = −1.78, p = 0.10, respectively, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Training distance and load throughout the 12-week training period in Year 1 and Year 2. Training distance Year 1 and training distance Year 2 are represented with black and gray bars, respectively, while training load Year 1 and training load Year 2 are represented with black and gray lines, respectively.

3.2. Changes in Swimming Performance, Tethered Swimming Force, Impulse, and Kinematic Variables

3.2.1. Swimming Performance

The swimmers demonstrated improvements in performance across the 50, 200, and 400 m front crawl tests following the 12-week training period in both years (F1,14 = 5.5 to 10.8, η2p = 0.28 to 0.44, p = 0.01 to 0.04, Table 1). However, no differences were observed in performance times between the training periods and years of training (η2p = 0.10 to 0.38; p = 0.11 to 0.98). Furthermore, the %Δ in performance from post- to pre-intervention was comparable across all swimming performance tests between the two training years (p = 0.23 to 0.89).

Table 1.

Performance time changes in the 50, 200, and 400 m front crawl tests were measured before (PRE) and after (POST) a 12-week training period across two years of training (Year 1 and Year 2).

3.2.2. Tethered Swimming Force and Impulse

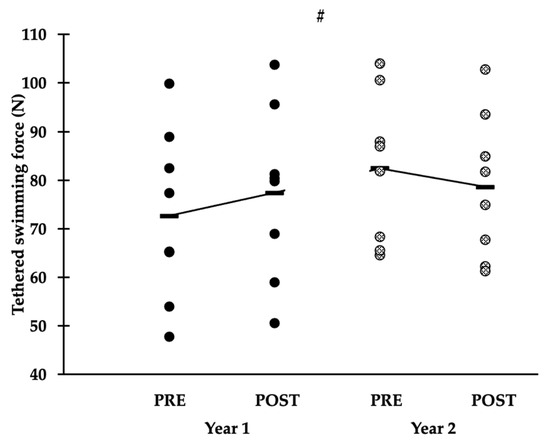

The mean TF increased after the 12-week training period in Year 1 (F1,14 = 14.57, η2p = 0.51, p = 0.01; Figure 3). Additionally, TFmax showed an increase in Year 1, whereas a decrease was observed in Year 2 (F1,14 = 19.99, η2p = 0.58, p = 0.01; Table 2). TFmin and FI remained unchanged across training periods and between the two twelve-week periods of training applied over two consecutive years (p = 0.45; Table 2). However, the %Δ in TFmax and TFmin from post- to pre-intervention differed between Year 1 and Year 2 (TFmax: t = 4.02, p = 0.01; TFmin: t = 2.37, p = 0.04).

Figure 3.

Mean tethered swimming force exerted by swimmers during a 30 s tethered swimming test, measured before (PRE) and after (POST) the 12-week training period in Year 1 and Year 2. # p < 0.05, indicating an interaction between the time points of measurement and the years of training.

Table 2.

Pre- and post- values of maximum and minimum tethered swimming force, as well as fatigue index during a 30 s tethered swimming sprint, following a twelve-week swimming training conducted during twelve weeks of training applied across two years.

The IMP decreased after the 12-week training period in Year 2 (F1,14 = 15.14, η2p = 0.52, p = 0.01; Figure 4). Furthermore, the %Δ in IMP from post- to pre-intervention differed between years (Year 1: 4.3 ± 6.8% vs. Year 2: −6.8 ± 4.5%, t = 3.64, p = 0.01).

Figure 4.

Swimmers’ impulse was calculated by the 30 s tethered swimming test, measured before (PRE) and after (POST) the 12-week training period in Year 1 and Year 2. # p < 0.05, indicating an interaction between the time points of measurement and the years of training.

3.2.3. Kinematic Variables

The swimmers’ SR during the 50, 200, and 400 m front crawl remained unchanged following the 12-week training period in both training years (50 m: η2p = 0.05; 200 m: η2p = 0.01; 400 m: η2p = 0.01; p = 0.30 to 0.50, Table 3). In contrast, SL increased in the 200 m test (η2p = 0.49), while SI increased in both the 200 m (η2p = 0.62) and 400 m (η2p = 0.30) front crawl tests after the training period in both years (p = 0.01, Table 3). However, the %Δ from post- to pre-intervention was similar for all kinematic variables in all performance tests (t = −1.22 to 0.69, p = 0.26 to 0.92).

Table 3.

Kinematic variable change in the 50, 200, and 400 m front crawl tests measured before (PRE) and after (POST) a 12-week training period across two years (Year 1 and Year 2).

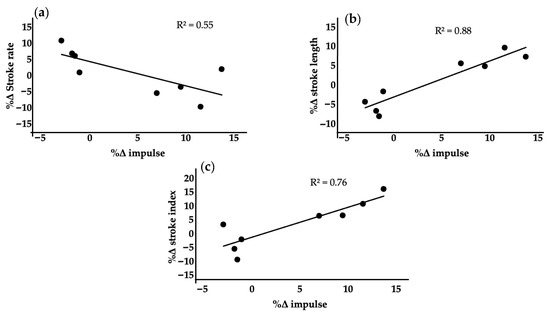

3.3. Correlations

A negative correlation was observed between IMP and SR during the 400 m front crawl in Year 1 (r = −0.74, 95% CI: −0.08, −0.95; Figure 5). In contrast, a positive correlation was identified between IMP and both SL (r = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.98, 0.68) and SI (r = 0.87, 95% CI: 0.97, 0.44) in the 400 m trial in Year 1 (Figure 5). However, in Year 2, no significant correlations were observed between IMP and SR (r = −0.45, 95% CI: 0.37, −0.87), SL (r = −0.30, 95% CI: 0.83, −0.51), or SI (r = –0.12, 95% CI: 0.76, −0.63) during the 400 m front crawl trial.

Figure 5.

Correlations between the percentage difference (%Δ) in impulse and stroke rate (a), stroke length (b), and stroke index (c) during the 400 m front crawl test in Year 1.

4. Discussion

The study examined the changes in tethered swimming force and selected kinematic variables after twelve weeks of swimming training across two years, and whether these changes were related to improvements in 50, 200, and 400 m swimming performance. Swimming performance improved in 50, 200, and 400 m front crawl tests following the 12-week training period. Also, the mean TF increased after the 12-week training period only during the first year, while IMP remained unchanged in the first year and decreased in the second. Regarding kinematic variables, SR remained stable across all distances, while SL and SI increased in the 200 and 400 m tests. The swimmers’ performance improved in all distances following the 12-week training period in both training years under the same training load.

These findings are consistent with previous studies confirming that 12 weeks of swimming training enhances performance in both short- (50 m) and middle-distance tests (200, 400 m [28]). Such improvements may be attributed to physiological adaptations developed over the 12-week training period, leading to an enhanced aerobic capacity due to the training process [29,30]. In addition to the improved aerobic capacity, biological maturation represents an important factor that is likely to have progressed over the study period. More specifically, maturation appears to affect the physiological characteristics of athletes by enhancing cardiorespiratory endurance [31,32]. Biological maturation seems to affect muscle strength, body size, and dimensions of the heart, lungs, and circulatory system, along with the maturation of central neurological factors [17,33,34].

Our findings indicate that the swimmers’ biological maturation increased following each training period across both training years. Correspondingly, they demonstrated improved performance times in all tests after the 12-week training intervention. However, a significant increase in TF was observed only during the first year of the training period. This outcome may be attributed to the athletes’ prior training experience (e.g., Year 1), as well as the unchanged training load in the second year, which may have been insufficient to induce further physiological or neuromuscular adaptations [17,35].

Regarding tethered swimming force characteristics, both force and impulse increased during the first year. Similar studies examining the effects of combined in-water and dry-land training have reported improvements in strength characteristics, either as a result of increased muscular strength or improved swimming technique [36]. However, in the second year, a decrease in the tethered force was observed after a training period of similar duration and training load. The same training load applied in the second year may have been insufficient to induce further adaptations in force production. Additionally, the sharp increase in the training load during the three weeks before the measurement, without the necessary rest period, such as a taper, may have negatively affected the swimmers’ performance in the tethered swimming test. Previous research has shown that periods of elevated training load can result in temporary reductions in strength and in-water propulsion [37,38].

Considering the kinematic variables, improvements in SL and SI were observed in the 200 m in both years, while only SI improved in the 400 m. The improvement of kinematic variables appears to be a crucial factor influencing performance—particularly in the 400 m event—during the maturation process of young swimmers. Furthermore, beyond their direct impact on performance [39], the increase in SL is likely to reflect improvements in the athletes’ physiological characteristics that resulted from the training process and enhancements in their technique. Fatigue during effort has been shown to reduce SL [40], suggesting that better-trained athletes can maintain or increase SL and SI. Additionally, technical characteristics play a crucial role in SL and SI, as high-level swimmers with better technique generate sufficient propulsive forces, leading to increased SL and SI [41]. Given that SL and SI are kinematic variables strongly associated with swimming efficiency—particularly in middle-distance events [1]—swimmers may benefit from enhancing in-water strength and technical efficiency through targeted training interventions [42].

Finally, a positive correlation between %Δ in SL and SI in the 400 m and %Δ IMP was observed, while a negative correlation of %Δ in SR in the 400 m with %Δ IMP and %Δ mean force was seen in the first year. The observations mentioned above emphasize the importance of in-water specific force development, which enhances the ability to apply propulsion, especially in middle-distance events. Additionally, a proper distribution and targeted increase in training load are crucial to induce continuous adaptations that support the athletes’ development. Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. The small sample size limits the possibility of generalizing with our results; both male and female swimmers participated, and anthropometric measurements were not taken at the end of each 12-week training period.

5. Conclusions

Improvements in swimming performance appear to be driven by enhancements in kinematic variables, especially SL and SI in middle-distance tests, which are closely linked to swimming efficiency. Biological maturation contributes to increased in-water strength parameters, such as tethered force and impulse, as well as to overall performance. However, maturation alone is insufficient; targeted increases in training load are necessary to induce further physiological and neuromuscular adaptations, supporting continued improvements in strength and performance. From a practical standpoint, coaches should adjust training loads in accordance with swimmers’ biological maturation, focusing on enhanced muscular adaptations to improve specific in-water force.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.A., I.S.N., I.C. and A.G.T.; methodology, G.G.A., I.S.N., I.C. and A.G.T.; software, G.G.A., I.S.N. and I.C.; validation, G.G.A. and A.G.T.; formal analysis, G.G.A.; investigation, G.G.A. and I.S.N.; resources, G.G.A. and I.S.N.; data curation, G.G.A. and I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.G.A., I.S.N. and I.C.; writing—review and editing, G.G.A., I.S.N., I.C. and A.G.T.; visualization, G.G.A., I.S.N. and I.C.; supervision, A.G.T.; project administration, G.G.A. and A.G.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Physical Education and Sports Science (1111/10-04-2019, approved on 10 April 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data could be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| TF | Tethered swimming force |

| TFmax | Maximum tethered force |

| TFmin | Minimum tethered force |

| IMP | Impulse |

| FI | Fatigue index |

| SR | Stroke rate |

| SL | Stroke length |

| SI | Stroke index |

References

- Barbosa, T.M.; Bragada, J.A.; Reis, V.M.; Marinho, D.A.; Carvalho, C.; Silva, A.J. Energetics and Biomechanics as Determining Factors of Swimming Performance: Updating the State of the Art. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 13, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsoniadis, G.; Botonis, P.; Bogdanis, G.C.; Terzis, G.; Toubekis, A. Acute and Long-Term Effects of Concurrent Resistance and Swimming Training on Swimming Performance. Sports 2022, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowski, K.; Bartolomeu, R.F.; Barbosa, T.M.; Strzała, M. VO2 Kinetics and Tethered Strength Influence the 200-m Front Crawl Stroke Kinematics and Speed in Young Male Swimmers. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 1045178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amara, S.; Chortane, O.G.; Negra, Y.; Hammami, R.; Khalifa, R.; Chortane, S.G.; Van Den Tillaar, R. Relationship between Swimming Performance, Biomechanical Variables and the Calculated Predicted 1-RM Push-up in Competitive Swimmers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loturco, I.; Barbosa, A.; Nocentini, R.; Pereira, L.; Kobal, R.; Kitamura, K.; Abad, C.; Figueiredo, P.; Nakamura, F. A Correlational Analysis of Tethered Swimming, Swim Sprint Performance and Dry-Land Power Assessments. Int. J. Sports Med. 2015, 37, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.C.; Marinho, D.A.; Costa, M.J. Changes in Young Swimmers’ In-Water Force, Performance, Kinematics, and Anthropometrics over a Full Competitive Season. J. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 93, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, K.; Pereira, G.; Papoti, M.; Bento, P.C.; Rodacki, A. Propulsive Force Asymmetry during Tethered-Swimming. Int. J. Sports Med. 2013, 34, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, M.; De Jesus, K.; De Souza Castro, F.A. Variables and Protocols of the Tethered Swimming Method: A Systematic Review. Sport Sci. Health 2024, 20, 535–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morouço, P.; Marinho, D.A.; Keskinen, K.L.; Badillo, J.J.; Marques, M.C. Tethered Swimming Can Be Used to Evaluate Force Contribution for Short-Distance Swimming Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 3093–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.A.D.S.; Oliveira, T.S.D.; Moré, F.C.; Mota, C.B. Relationship between 200m Front Crawl Stroke Performance and Tethered Swimming Test Kinetics Variables. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Esporte 2010, 31, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalva-Filho, C.; Zagatto, A.; Da Silva, A.; Castanho, M.; Gobbi, R.; Gobatto, C.; Papoti, M. Relationships among the Tethered 3-Min All-Out Test, MAOD and Swimming Performance. Int. J. Sports Med. 2017, 38, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalkiadakis, I.; Arsoniadis, G.G.; Toubekis, A.G. Dry-Land Force–Velocity, Power–Velocity, and Swimming-Specific Force Relation to Single and Repeated Sprint Swimming Performance. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2023, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Navarro, J.J.; Gay, A.; Cuenca-Fernández, F.; López-Belmonte, Ó.; Morales-Ortíz, E.; López-Contreras, G.; Arellano, R. The Relationship between Tethered Swimming, Anaerobic Critical Velocity, Dry-Land Strength, and Swimming Performance. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2022, 22, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, E.; Harrison, A.J.; Lyons, M. The Impact of Resistance Training on Swimming Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2285–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lätt, E.; Jürimäe, J.; Haljaste, K.; Cicchella, A.; Purge, P.; Jürimäe, T. Longitudinal Development of Physical and Performance Parameters during Biological Maturation of Young Male Swimmers. Percept. Mot. Skills 2009, 108, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lätt, E.; Jürimäe, J.; Mäestu, J.; Purge, P.; Rämson, R.; Haljaste, K.; Rodriguez, F.A.; Jürimäe, T. Physiological, Biomechanical and Anthropometrical Predictors of Sprint Swimming Performance in Adolescent Swimmers. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2010, 9, 398–404. [Google Scholar]

- Lobato, C.H.; De Lima Rocha, M.; De Almeida-Neto, P.F.; De Araújo Tinôco Cabral, B.G. Influence of Advancing Biological Maturation in Months on Muscle Power and Sport Performance in Young Swimming Athletes. Sport Sci. Health 2023, 19, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Henrique, R.S.; Queiroz, D.R.; Salvina, M.; Melo, W.V.; Moura Dos Santos, M.A. Anthropometric Variables, Propulsive Force and Biological Maturation: A Mediation Analysis in Young Swimmers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 21, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujika, I.; Busso, T.; Lacoste, L.; Barale, F.; Geyssant, A.; Chatard, J.-C. Modeled Responses to Training and Taper in Competitive Swimmers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, J.M.; Whitehouse, R.H. Clinical Longitudinal Standards for Height, Weight, Height Velocity, Weight Velocity, and Stages of Puberty. Arch. Dis. Child. 1976, 51, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, J.M. The Measurement of Maturity. Trans. Eur. Orthod. Soc. 1975, 51, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman-Verhoeff, M.E.; Gredvig-Ardito, C.; Barker, D.H.; Saletin, J.M.; Carskadon, M.A. Classifying Pubertal Development Using Child and Parent Report: Comparing the Pubertal Development Scales to Tanner Staging. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubekis, A.G.; Gourgoulis, V.; Tokmakidis, S.P. (Eds.) Tethered Swimming as an Evaluation Tool of Single Arm-Stroke Force. In Proceedings of the XIth International Symposium for Biomechanics and Medicine in Swimming, Oslo, Norway, 16–19 June 2010; Norwegian School of Sport Sciences: Oslo, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Morouço, P.; Keskinen, K.L.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Fernandes, R.J. Relationship Between Tethered Forces and the Four Swimming Techniques Performance. J. Appl. Biomech. 2011, 27, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; L. Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-8058-0283-2. [Google Scholar]

- Karabıyık, H.; Gülü, M.; Yapici, H.; Iscan, F.; Yagin, F.H.; Durmuş, T.; Gürkan, O.; Güler, M.; Ayan, S.; Alwhaibi, R. Effects of 12 Weeks of High-, Moderate-, and Low-Volume Training on Performance Parameters in Adolescent Swimmers. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsoniadis, G.G.; Botonis, P.G.; Nikitakis, I.S.; Kalokiris, D.; Toubekis, A.G. Effects of Successive Annual Training on Aerobic Endurance Indices in Young Swimmers. Open Sports Sci. J. 2017, 10, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Machado, M.V.; Júnior, O.A.; Marques, A.C.; Colantonio, E.; Cyrino, E.S.; De Mello, M.T. Effect of 12 Weeks of Training on Critical Velocity and Maximal Lactate Steady State in Swimmers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2011, 11, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubekis, A.G.; Tsami, A.P.; Smilios, I.G.; Douda, H.T.; Tokmakidis, S.P. Training-Induced Changes on Blood Lactate Profile and Critical Velocity in Young Swimmers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebestreit, H.; Bar-Or, O. The Young Athlete. In Encyclopaedia of Sports Medicine; IOC Medical Commission, International Federation of Sports Medicine, Eds.; Blackwell Pub: Malden, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4051-5647-9. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, T.; Murara, P.; Vancini, R.; Lira, C.; Andrade, M. Influence of Biological Maturity on the Muscular Strength of Young Male and Female Swimmers. J. Hum. Kinet. 2021, 78, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dampney, R.A.L. Central Neural Control of the Cardiovascular System: Current Perspectives. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2016, 40, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.S.; Oliver, J.L. The Youth Physical Development Model: A New Approach to Long-Term Athletic Development. Strength Cond. J. 2012, 34, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspenes, S.; Kjendlie, P.-L.; Hoff, J.; Helgerud, J. Combined Strength and Endurance Training in Competitive Swimmers. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2009, 8, 357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costill, D.L.; Thomas, R.; Robergs, R.A.; Pascoe, D.; Lambert, C.; Barr, S.; Fink, W.J. Adaptations to Swimming Training: Influence of Training Volume. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1991, 23, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoti, M.; Martins, L.E.B.; Cunha, S.A.; Zagatto, A.M.; Gobatto, C.A. Effects of Taper on Swimming Force and Swimmer Performance After an Experimental Ten-Week Training Program. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lätt, E.; Jürimäe, J.; Haljaste, K.; Cicchella, A.; Purge, P.; Jürimäe, T. Physical Development and Swimming Performance During Biological Maturation in Young Female Swimmers. Coll. Antropol. 2009, 33, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Alberty, M.; Sidney, M.; Pelayo, P.; Toussaint, H.M. Stroking Characteristics during Time to Exhaustion Tests. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomax, M.; Castle, S. Inspiratory Muscle Fatigue Significantly Affects Breathing Frequency, Stroke Rate, and Stroke Length during 200-m Front-Crawl Swimming. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 2691–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkoumas, I.; Gourgoulis, V.; Aggeloussis, N.; Antoniou, P. The Influence of an 11-Week Resisted Swim Training Program on the Inter-Arm Coordination in Front Crawl Swimmers. Sports Biomech. 2023, 22, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).