Quantitative Reliability Evaluation for Cryogenic Impact Test Equipment

Abstract

1. Introduction

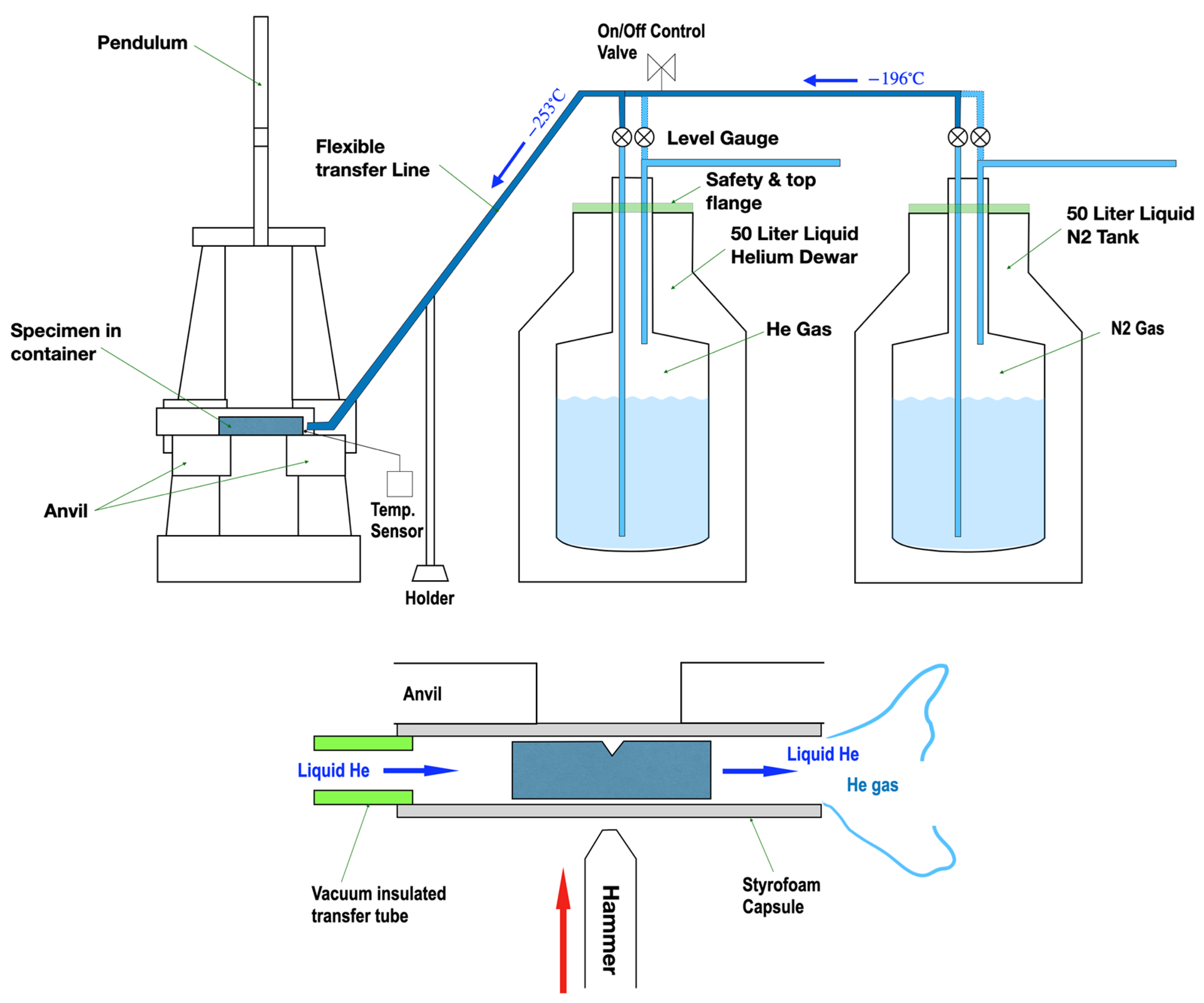

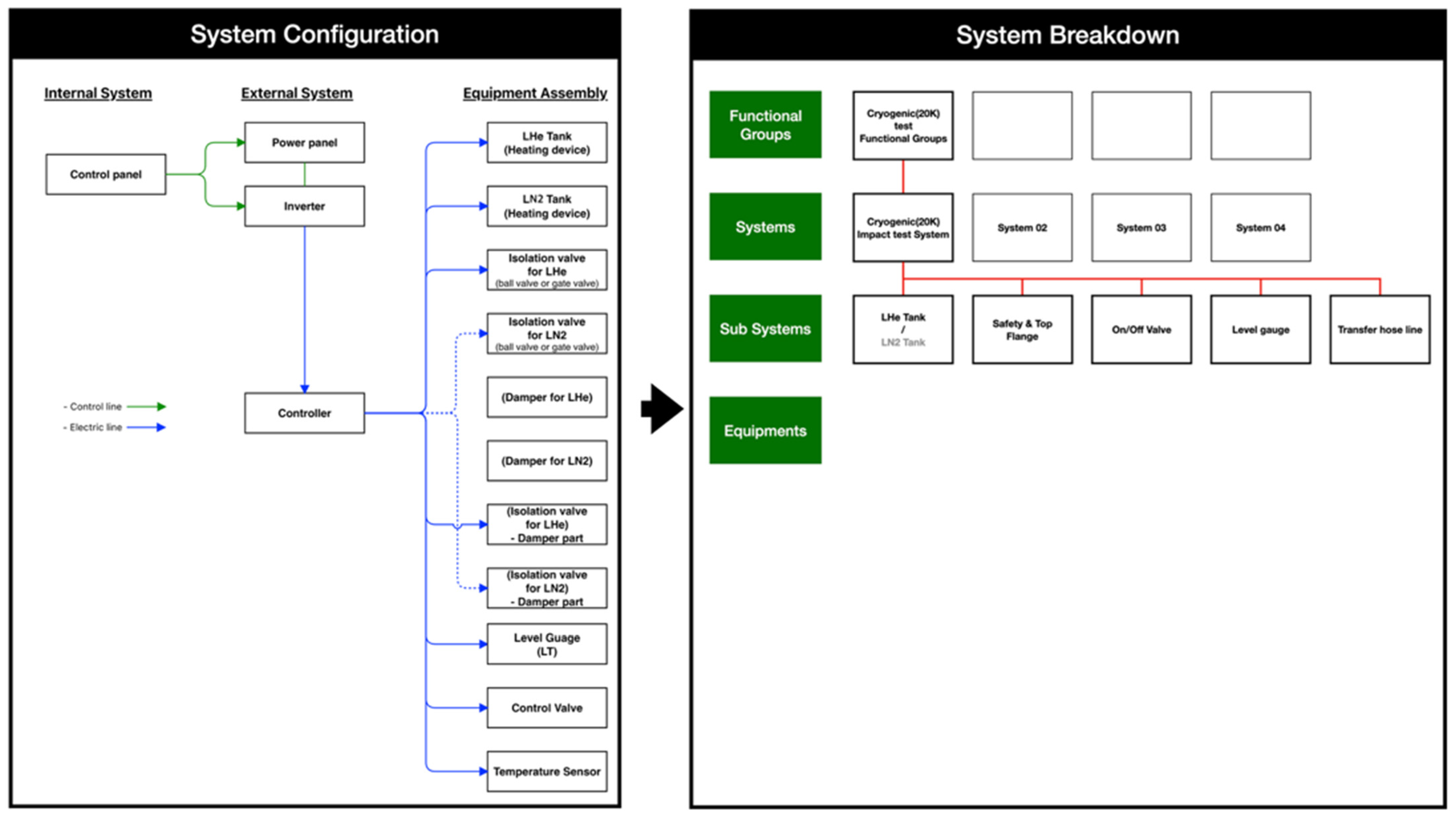

2. Ultra-Low Temperature Shock Test Equipment

3. Function and Failure Mode Analysis of Ultra-Low Temperature Shock Test Equipment

3.1. Functional Analysis

- (a)

- Liquid helium tank: Equipment for storing and transferring cryogenic fluid at −269 °C, consisting of a double-insulated vessel made up of an inner shell that directly contains the liquid helium and an outer shell surrounding it. The space between the inner and outer shells is formed as a vacuum, and glass wool or powdered insulation may be filled inside this vacuum-insulated space.

- (b)

- Liquid nitrogen tank: Equipment for storing and transferring cryogenic fluid at −196 °C, consisting of a double-insulated vessel made up of an inner shell that directly contains the liquid nitrogen and an outer shell surrounding it. The space between the inner and outer shells is formed as a vacuum, and glass wool or powdered insulation may be filled inside this vacuum-insulated space.

- (c)

- Safety and top flange: A device that safely maintains the vacuum insulation performance and pressure of the liquid helium and liquid nitrogen tanks, ensuring stable retention of the vacuum and coolant.

- (d)

- On/off valve: A device that controls coolant switching based on temperature values measured by a temperature sensor. When liquid helium is supplied to the cryogenic supply line through the liquid helium extraction pipe, the valve closes. When liquid nitrogen is supplied to the cryogenic supply line through the liquid nitrogen extraction pipe, the valve opens.

- (e)

- Level gauge: A device that mechanically measures the fluid level inside the liquid helium and liquid nitrogen tanks and enables on/off operation by valve control according to the measured level.

- (f)

- Transfer hose line: Vacuum-insulated equipment for delivering cryogenic fluid at −253 °C to the impact test specimen, allowing for the continuous transfer of coolant while maintaining the set temperature.

- (g)

- Container (Styrofoam capsule): A container used to cool the impact test specimen to the target temperature in a cryogenic environment and then perform the test. Coolant inflow forms the interior into a cryogenic environment, and the supplied coolant maintains the specimen at the target temperature. The container housing the specimen is made of a Styrofoam capsule, arranged so that the specimen and container are broken together by the hammer, integrated as part of the system.

3.2. Failure Mode Effect and Criticality Analysis (FMECA)

- (a)

- Definition and refinement of the system to be analyzed;

- (b)

- Determination of the FMECA worksheet (selection of analysis items);

- (c)

- Functional and fault analysis;

- (d)

- FMECA team review;

- (e)

- Verification and implementation of improvement measures.

- (a)

- Item title: Name of the subsystem;

- (b)

- Function: Describes the operation and role of units or components, but is limited to the functions of subsystems due to the structure of the cryogenic (20 K) impact test system;

- (c)

- Failure mode: Types of failures classified according to their functions;

- (d)

- Failure cause: Causes of each failure type or multiple root causes for a single failure;

- (e)

- Failure detection: Methods for detecting issues within subsystems or units;

- (f)

- Failure effect: The impact of each failure on the system, the environment, or personnel interacting with the system;

- (g)

- Criticality: The risk level expressed as high or low based on failure frequency and potential damage.

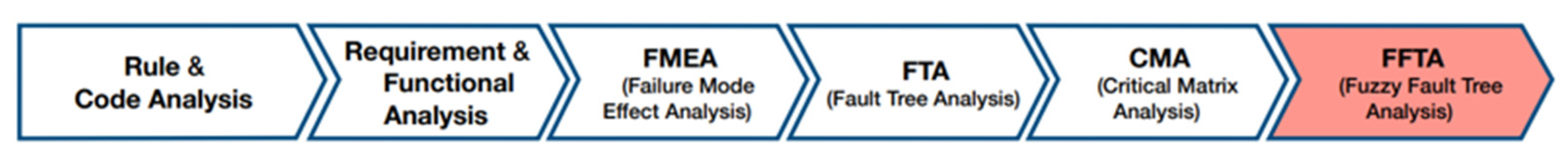

4. Failure Probability Based Reliability Result of Ultra-Low Temperature Shock Test Equipment

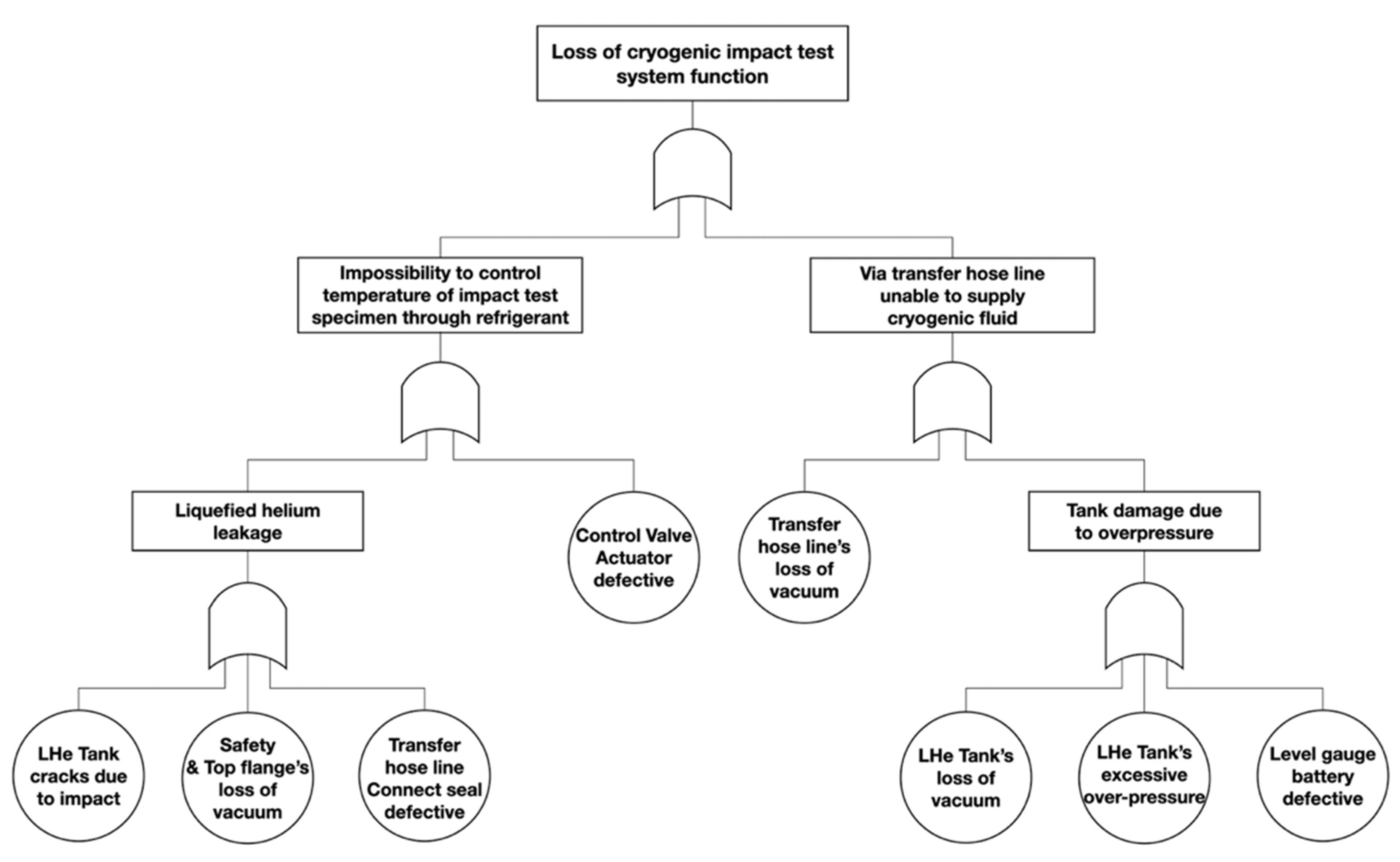

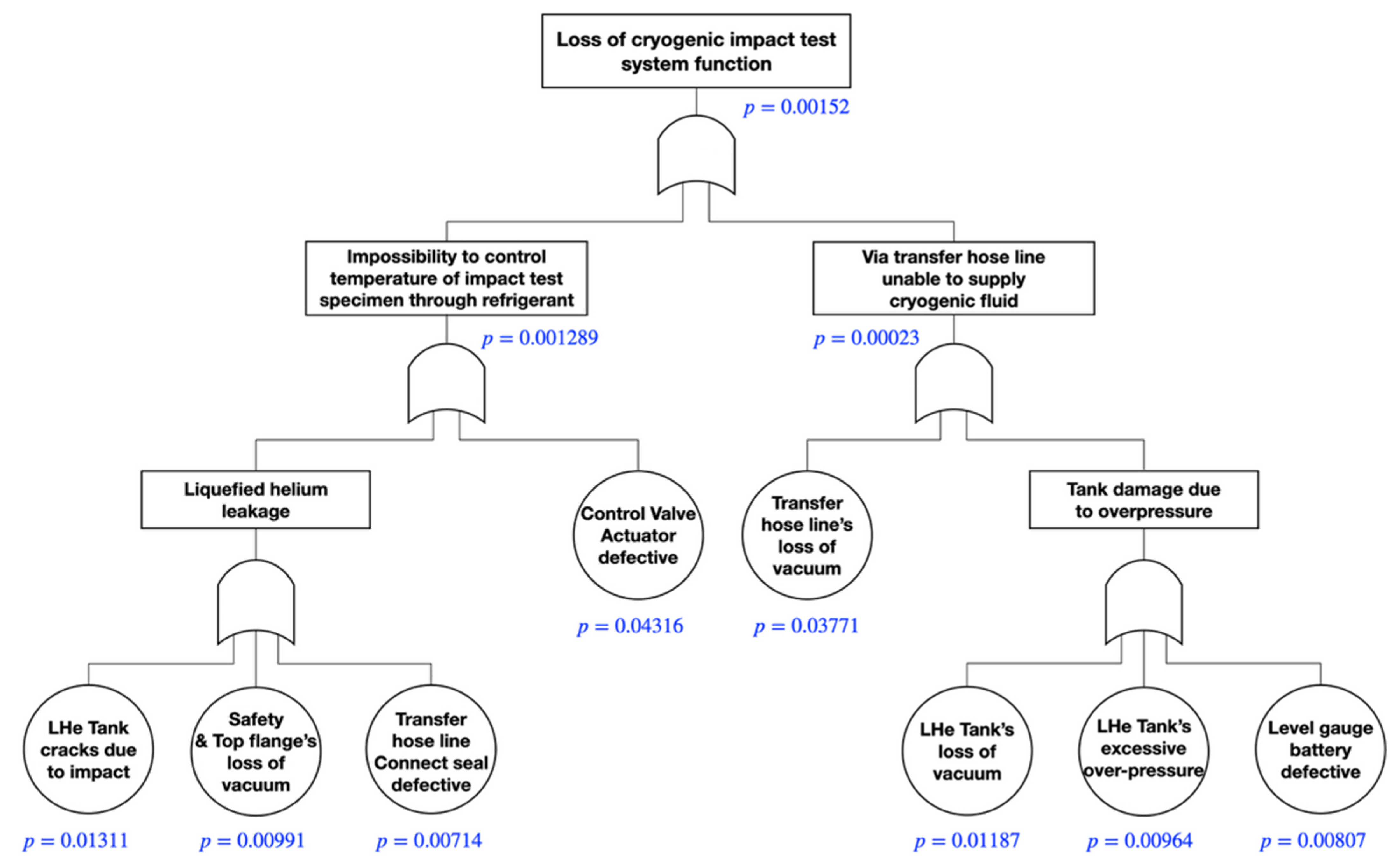

4.1. Fault Tree Analysis (FTA)

- (a)

- Example: “External impact”;

- (b)

- Example: “Vibration”;

- (c)

- Example: “Excessive pressure rise”.

- (a)

- Cracks caused by impact;

- (b)

- Vibration;

- (c)

- Vacuum failure;

- (d)

- Excessive pressure rise;

- (e)

- Actuator malfunction;

- (f)

- Faulty connection;

- (g)

- Battery malfunction;

- (h)

- Moisture intrusion;

- (i)

- Long-term use;

- (j)

- Defective connected seal.

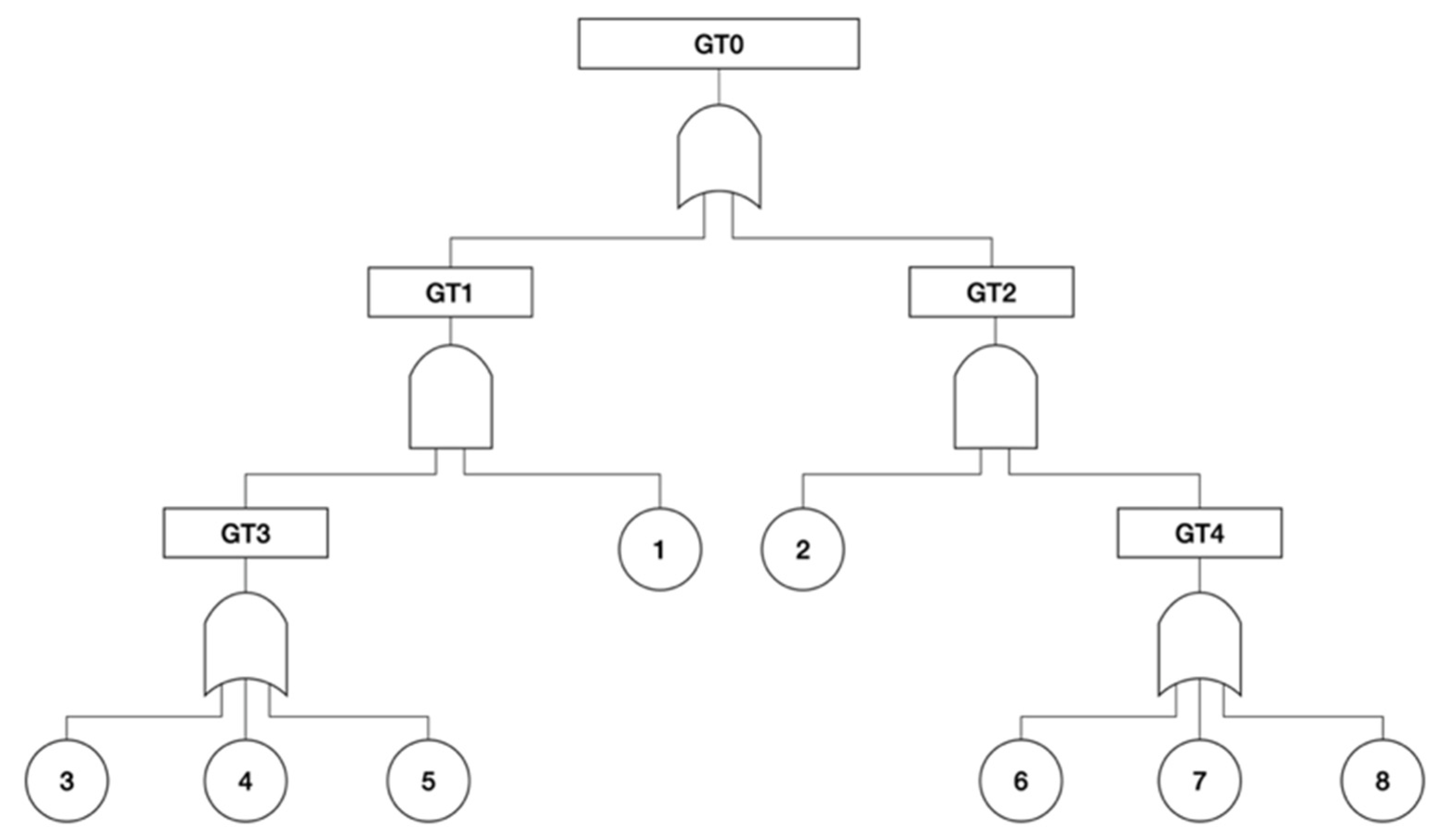

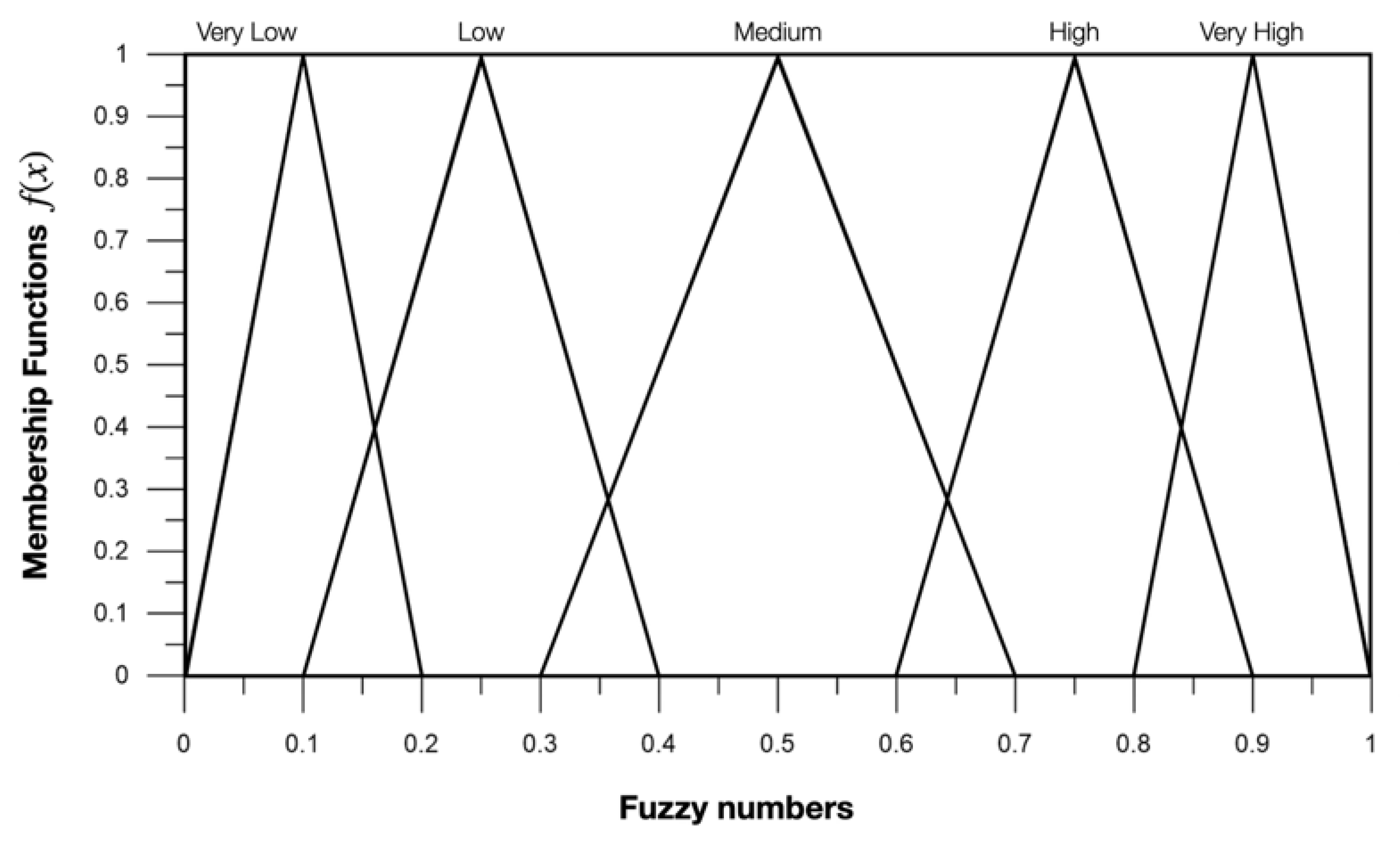

4.2. Fuzzy Fault Tree Analysis (F-FTA)

4.2.1. Failure Probabilities of the Basic Events

4.2.2. Expert Elicitation

4.2.3. Linguistic Expression to Fuzzy Numbers

4.2.4. Estimates of the Basic Events

4.2.5. Converting Fuzzy Possibility

4.3. Failure Probability of the Top Event

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASME | American Society of Mechanical Engineers |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| BEs | Basic events |

| FMEA | Failure Modes and Effects Analysis |

| FMECA | Failure Modes, Effects, and Criticality Analysis |

| FPS | Fuzzy possibility score |

| FTA | Fault tree analysis |

| IACS | International Association of Classification Societies |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LHe | Liquid helium |

| LNG | Liquefied natural gas |

| MCS | Minimal cut set |

| RBD | Reliability block diagram |

| TE | Top event |

References

- National Fire Protection Association. NFPA 2: Hydrogen Technologies Code; NFPA: Quincy, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 21009-1; Cryogenic Vessels—Static Vacuum-Insulated Vessels—Part 1: Design, Fabrication, Inspection and Testing. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO 21009-2; Cryogenic Vessels—Static Vacuum-Insulated Vessels—Part 2: Operational Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO/TR 15916; Basic Considerations for the Safety of Hydrogen Systems. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- MSC.420(97); Interim Recommendations for Carriage of Liquefied Hydrogen in Bulk. International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 2017.

- DNV. IMO CCC 11: Interim Guidelines for Hydrogen as Fuel Completed. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/news/2025/imo-ccc-11-interim-guidelines-for-hydrogen-as-fuel-completed/ (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- ASTM A333/A333M; Standard Specification for Seamless and Welded Steel Pipe for Low-Temperature Service. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code (BPVC). Section VIII: Rules for Construction of Pressure Vessels; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ASME B31.12-2023; Hydrogen Piping and Pipelines. American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME): New York, NY, USA, 2023.

- Kim, M.-S.; Lee, T.; Son, Y.; Park, J.; Kim, M.; Eun, H.; Park, J.-W.; Kim, Y. Metallic Material Evaluation of Liquid Hydrogen Storage Tank for Marine Application Using a Tensile Cryostat for 20 K and Electrochemical Cell. Processes 2022, 10, 2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobola, D.; Dallaev, R. Exploring Hydrogen Embrittlement: Mechanisms, Consequences, and Advances in Metal Science. Energies 2024, 17, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). International Code of Safety for Ships Using Gases or Other Low-Flashpoint Fuels (IGF Code); IMO: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Association of Classification Societies (IACS). Unified Requirement M74—Material Requirements for Cryogenic Service; IACS: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MIL-STD-1629A; Procedures for Performing a Failure Mode, Effects and Criticality Analysis (FMECA). Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 1980.

- OREDA. Offshore and Onshore Reliability Data Handbook, 6th ed.; OREDA Participants: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, K.B.; Weber, G.G. Use of Fuzzy Set Theory for Level-I Studies in Probabilistic Risk Assessment. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1990, 37, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarres, M. Risk Analysis in Engineering: Probabilistic Techniques; CRC Publishing: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, P.V.; Babar, A.K.; Raj, V.V. Uncertainty in Fault Tree Analysis: A Fuzzy Approach. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1996, 83, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisawa, T.; Kacprzyk, J. Reliability and Safety Analyses Under Fuzziness; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, S.; Papadopoulos, Y. Applications of Bayesian networks and fuzzy logic for safety, reliability, and risk assessments: A review. Saf. Sci. 2019, 115, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Sachan, D.; Verma, R.; Goel, S.; Jayaganthan, R.; Kumar, A. Mechanical behavior of 304 Austenitic Stainless Steel Processed by Cryogenic Rolling. Mater. Proc. 2018, 5 Pt 1, 16880–16886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6892-4:2015; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 4: Verification of Extensometers Used in Uniaxial Testing. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63645.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Umezawa, O. Review of the Mechanical Properties of High-Strength Alloys at Cryogenic Temperatures. Mater. Perform. Charact. 2021, 10, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, B.S.; Fabrycky, W.J. Systems Engineering and Analysis, 5th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NASA. NASA Systems Engineering Handbook; NASA/SP-2007-6105 Rev2; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- IEC 60812; Analysis Techniques for System Reliability—Procedure for Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA). International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- McDermott, R.E.; Mikulak, R.J.; Beauregard, M.R. The Basics of FMEA, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vesely, W.E.; Goldberg, F.F.; Roberts, N.H.; Haasl, D.F. Fault Tree Handbook; U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NUREG-0492): Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- IEC 61025; Fault Tree Analysis (FTA). International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Purba, J.H. Fuzzy Probability on Reliability Study of Nuclear Power Plant Probabilistic Safety Assessment: A review. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2014, 76, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.M. Experts in Uncertainty: Opinion and Subjective Probability in Science; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.J.; Hwang, C.L. Fuzzy Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Clemen, R.T.; Winkler, R.L. Combining probability distributions from experts in risk analysis. Risk Anal. 1999, 19, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onisawa, T. An approach to human reliability in man–machine systems using error possibility. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1988, 27, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item Description | Failure Description | Failure Effect Description | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Components | Function | Failure Modes | Failure Mechanisms | Failure Cause | Criticality | ||

| F | S | C | |||||

| LHe tank | A device designed to store and transport cryogenic fluid at −269 °C, with the capability to transfer fluid at temperatures as low as −253 °C, the temperature of liquid hydrogen. | Leakage | Crack due to impact | Design fault, insufficient mechanical strength of materials, and machining defects | Low | High | 5 |

| Valve or pipe detachment | Vibration | Design fault | Low | Mid. | 3 | ||

| Inaccuracy of various gauges | Vibration | Manufacturing fault | Low | Mid. | 3 | ||

| Container explosion due to pressure rise | Vacuum failure | Assembly fault | Mid. | High | 7 | ||

| Container rupture or damage | Excessive pressure rise | Design fault | Low | High | 5 | ||

| Safety and top flange | A safety device designed to prevent fluid leakage by ensuring vacuum insulation performance and managing pressure in the liquid helium and liquid nitrogen tanks. | Leakage caused by seal damage | Vacuum failure | Manufacturing fault | Mid. | High | 7 |

| On/off valve | The function to close the valve once the fluid in the liquid nitrogen tank reaches the set temperature of −196 °C, and to keep the valve open while the fluid is reaching the set temperature. | Loss of automatic functionality due to actuator malfunction. | Actuator fault | Assembly fault | Low | High | 5 |

| Leakage caused by a faulty connection. | Connection fault | Design fault | Low | High | 5 | ||

| Level gauge | A device that mechanically measures the liquid level in the liquid helium and liquid nitrogen tanks, with the ability to control the valve for on/off operation based on the measured fluid level. | Inability to measure capacity. | Battery malfunction. | Vacuum fault | Low | High | 5 |

| Overfilling of the tank due to an inability to determine the liquid level could lead to an explosion risk. | Battery malfunction. | Material fault | Low | High | 5 | ||

| Inability to measure capacity due to circuit malfunction. | Moisture intrusion. | Design fault, insufficient mechanical strength of materials, and machining defects | Low | Mid. | 3 | ||

| Transfer hose line | A vacuum-insulated device designed to transport cryogenic fluid at −253 °C to the impact test specimen, with the capability to continuously transfer the fluid while maintaining the set temperature. | Loss of functionality due to decreased insulation performance. | Vacuum failure | Design fault, insufficient mechanical strength of materials, and machining defects | Mid. | High | 7 |

| Damage due to loss of flexibility from residual stress | Long term use | Design fault | Low | Mid. | 3 | ||

| Occurrence of LHe leakage. | Fault of connected seal | Manufacturing fault | Low | High | 5 | ||

| Parameter | Definition | Quantitative Scale (Level) | Typical Quantitative Code for Computation | Weight Factor | Description/Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failure (F) | Frequency of occurrence of a failure mode within the system | Low = Rare event, failure unlikely during operation Medium = Occasional failure under certain conditions High = Frequent or recurring failure during service life | Low = 1 Medium = 3 High = 5 | 0.30 | Represents how often a particular failure mode is expected to occur within the system |

| Severity (S) | Consequence of failure of system performance and safety | Low = Negligible effect on system performance or safety Medium = Partial performance loss, minor safety impact High = System shutdown or significant safety risk | Low = 1 Medium = 3 High = 5 | 0.40 | Indicates the degree of impact of damage caused by the failure |

| Criticality (C) | Combined impact index evaluating the overall importance of a failure mode | Low = Easily controllable, minimal impact (1 ≤ C ≤ 3) Medium = Noticeable impact requiring monitoring (4 ≤ C ≤ 6) High = Major impact requiring immediate corrective action (7 ≤ C ≤ 9) | Computed as normalized function of (F ∗ S) | 0.30 | Expresses the overall importance of each failure mode for risk ranking and prioritization |

| Title/Designation | Experience [Year] | Education Level | Age [Year] | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professor/Senior Manager | >30 | Doctor | >50 | 5 |

| Associate Professor/Manager | 20~30 | Doctor | 40~50 | 4 |

| Assistant Professor/ Assistant Manager | 10~20 | Doctor | 30~40 | 3 |

| Lecturer/Senior Officer | 5~10 | Bachelor | 25~30 | 2 |

| Worker/Officer | <5 | Bachelor | <25 | 1 |

| Expert No. | Title | Experience [Year] | Education | Age [Year] | Weighting Score | Weighting Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Professor | >30 | Doctor | >50 | 19 | 0.12338 |

| 2 | Manager | 10~20 | Masters | 40~50 | 15 | 0.09740 |

| 3 | Associate Professor | 10~20 | Doctor | 30~40 | 14 | 0.090901 |

| 4 | Associate Professor | 20~30 | Doctor | 40~50 | 16 | 0.10390 |

| 5 | Worker | 20~30 | Bachelor | 40~50 | 11 | 0.07143 |

| 6 | Worker | >30 | Bachelor | >50 | 13 | 0.08442 |

| 7 | Professor | 10~20 | Doctor | 30~40 | 16 | 0.10390 |

| 8 | Manager | 5~10 | Masters | 30~40 | 13 | 0.08442 |

| 9 | Senior Manager | >30 | Masters | >50 | 19 | 0.12338 |

| 10 | Professor | >30 | Doctor | 40~50 | 18 | 0.11688 |

| SUM | 154 | 1.00000 |

| BE | Expert No. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 1 | VH | VH | H | H | VH | VH | VH | H | H | VH |

| 2 | VH | VH | H | H | VH | VH | H | H | VH | H |

| 3 | H | H | M | H | H | H | M | H | M | H |

| 4 | M | M | H | H | M | H | M | H | M | H |

| 5 | M | M | H | M | H | H | M | M | M | M |

| 6 | M | H | M | H | M | H | M | H | H | H |

| 7 | H | H | M | M | H | H | M | H | M | H |

| 8 | H | M | H | M | M | L | M | H | M | H |

| SUM | ||||||||||

| a | b | c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VL | Very low | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| L | Low | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.4 |

| M | Medium | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| H | High | 0.6 | 0.75 | 0.9 |

| VH | Very high | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| BE(Xi) | Aggregated Fuzzy Number (M) | FPS | P(Xi) | Rank | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b | c | d | ||||||

| X1 | 0.7195 | 0.8396 | 0.8994 | 0.9597 | 0.25043 | 0.90508 | 0.8273 | 0.04316 | 1 |

| X2 | 0.7000 | 0.8250 | 0.8750 | 0.9500 | 0.26667 | 0.88372 | 0.8085 | 0.03771 | 2 |

| X3 | 0.5045 | 0.6705 | 0.6705 | 0.8364 | 0.42495 | 0.71735 | 0.6462 | 0.01311 | 3 |

| X4 | 0.4442 | 0.6201 | 0.6201 | 0.7961 | 0.47267 | 0.67697 | 0.6022 | 0.00991 | 5 |

| X5 | 0.3740 | 0.5617 | 0.5617 | 0.7494 | 0.52706 | 0.63095 | 0.5519 | 0.00714 | 8 |

| X6 | 0.4831 | 0.6526 | 0.6526 | 0.8221 | 0.44198 | 0.70294 | 0.6305 | 0.01187 | 4 |

| X7 | 0.4383 | 0.6153 | 0.6153 | 0.7922 | 0.47724 | 0.67310 | 0.5979 | 0.00964 | 6 |

| X8 | 0.4078 | 0.5828 | 0.5828 | 0.7578 | 0.50401 | 0.64493 | 0.5705 | 0.00807 | 7 |

| Inability to Control Temperature via Refrigerant—Part 1 | Inability to Control Temperature via Refrigerant—Part 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal cut set | K1 | K2 | K3 | K4 | K5 | K6 | K7 | K8 |

| Basic event | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2 |

| P(Ci) | 0.01131 | 0.00991 | 0.00714 | 0.04316 | 0.01187 | 0.00964 | 0.00807 | 0.03771 |

| P(T) | 0.001289 | 0.00023 | ||||||

| Probability of loss of function | 0.00152 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bae, J.I.; Park, Y.I.; Kim, J.-H. Quantitative Reliability Evaluation for Cryogenic Impact Test Equipment. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11280. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011280

Bae JI, Park YI, Kim J-H. Quantitative Reliability Evaluation for Cryogenic Impact Test Equipment. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(20):11280. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011280

Chicago/Turabian StyleBae, Jae Il, Young IL Park, and Jeong-Hwan Kim. 2025. "Quantitative Reliability Evaluation for Cryogenic Impact Test Equipment" Applied Sciences 15, no. 20: 11280. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011280

APA StyleBae, J. I., Park, Y. I., & Kim, J.-H. (2025). Quantitative Reliability Evaluation for Cryogenic Impact Test Equipment. Applied Sciences, 15(20), 11280. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152011280