Abstract

Medical endoscopic video processing requires real-time execution of color component acquisition, color filter array (CFA) demosaicing, and high dynamic range (HDR) compression under low-light conditions, while adhering to strict thermal constraints within the surgical handpiece. Traditional hardware-aware neural architecture search (NAS) relies on fixed hardware design spaces, making it difficult to balance accuracy, power consumption, and real-time performance. A collaborative “power-accuracy” optimization method is proposed for hardware-aware NAS. Firstly, we proposed a novel hardware modeling framework by abstracting FPGA heterogeneous resources into unified cell units and establishing a power–temperature closed-loop model to ensure that the handpiece surface temperature does not exceed clinical thresholds. In this framework, we constrained the interstage latency balance in pipelines to avoid routing congestion and frequency degradation caused by deep pipelines. Then, we optimized the NAS strategy by using pipeline blocks and combined with a hardware efficiency reward function. Finally, color component acquisition, CFA demosaicing, dynamic range compression, dynamic precision quantization, and streaming architecture are integrated into our framework. Experiments demonstrate that the proposed method achieves 2.8 W power consumption at 47 °C on a Xilinx ZCU102 platform, with a 54% improvement in throughput (vs. hardware-aware NAS), providing an engineer-ready lightweight network for medical edge devices such as endoscopes.

1. Introduction

Medical endoscopic video processing faces extreme thermal constraints requiring power consumption below 3 W to maintain surgical handpiece temperatures at or under 50 °C [1,2,3], driven by the miniaturization of devices with diameters not exceeding 3 cm [4,5]. Simultaneously, it demands real-time, frame-by-frame execution of computationally intensive tasks, including high dynamic range compression [6,7,8,9] and continuous color reconstruction under low-light conditions [10] to ensure diagnostic-quality video output for clinical decision-making. Data acquisition modules in medical devices such as white light/fluorescence endoscopes must be deployed directly within the surgical handpiece, where thermal management and power consumption are severely limited [10]. Excessive temperature may burn patient tissue and interfere with surgical operation, and the miniaturized design (diameter ≤3 cm) further restricts heat dissipation capability [4]. Moreover, to achieve clinically usable image quality under low illumination, the system must perform complex processing at the lens end, including color filter array (CFA) acquisition, real-time exposure adjustment, tone mapping, and high dynamic range (HDR) compression [6]. Conventional solutions relying on CPU/GPU computation often exceed 10 W of power consumption (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA)) [11], causing the handpiece surface temperature to exceed 60 °C [1], which fails to meet surgical safety requirements.

Hardware-aware neural architecture search (NAS) has shown significant potential in medical imaging, particularly for low-light endoscopic image reconstruction tasks, such as CFA demosaicing and dynamic range compression [12,13]. It can automatically generate lightweight network architectures to achieve high accuracy and real-time processing under strict power constraints while avoiding the overparameterization issues of manually designed networks [14,15,16,17,18]. Deep learning methods have been widely adopted in image reconstruction in recent years and significantly outperform traditional algorithms in terms of reconstruction quality [19,20,21]. However, manually designed networks often suffer from overparameterization and are difficult to adapt to hardware resource limits [22,23]. Neural architecture search (NAS), which automates network structure generation and optimizes the balance between accuracy and efficiency for specific scenarios, offers a viable path to overcome the bottlenecks of medical edge computing [14]. However, most existing NAS methods rely on GPU-based searches and do not consider the joint constraints of power, temperature, and area [24,25], making the generated models difficult to deploy directly on medical devices [26,27].

In the context of medical endoscopic imaging, FPGAs have become the hardware of choice due to their reconfigurability, high parallel computing capability, and ultralow power consumption, making them essential for meeting the ≤3 W power constraint in surgical handpieces as seen in Table 1. Field-programmable gate array is a reconfigurable silicon chip whose circuitry can be rewired post-manufacturing—analogous to building custom Lego machinery rather than using pre-assembled toys. This enables ultra-parallel processing at 1/3 the power of CPUs/GPUs, critical for real-time medical imaging under thermal constraints. The core of an FPGA consists of programmable logic units such as Xilinx CLBs/Intel ALMs, block memory (BRAM), and digital signal processors (DSPs). Through pipelined architectures and dataflow optimization, significant improvements in energy efficiency can be achieved. For example, the Xilinx Zynq-7000 (xilinx, San, Jose, CA, USA) consumes only 1/6 the power of a comparable GPU in image processing tasks while supporting hardware-level customized computing unit design, providing fundamental support for real-time low-power medical imaging [28].

Table 1.

Performance comparison of hardware platforms for endoscopic imaging.

To address the conflicting challenges of thermal dissipation limitations in surgical handpieces and high-accuracy real-time imaging under low-light conditions in medical endoscopy, this paper proposes a hardware-aware NAS framework oriented toward FPGA deployment, establishing for the first time a closed-loop connection between power constraints and neural architecture search. First, FPGA resources are abstracted into unified cell units, and surgical temperature thresholds are converted into upper limits on the number of cells via a thermodynamic model. Second, a “pipeline block” is introduced as a basic unit to jointly optimize network operations and balance the interstage pipeline latency, thereby avoiding frequency degradation caused by deep pipelines. Third, an enumeration-pruning strategy is adopted to generate plug-and-play lightweight networks that achieve 38.2 dB CPSNR reconstruction accuracy under a 90-cell constraint while operating at a low temperature of 47 °C, promoting the practical deployment of endoscopic imaging systems.

2. Related Work

2.1. Technologies for Low-Power Medical Imaging

Medical endoscopic imaging requires the acquisition of color components (e.g., Bayer patterns) through a color filter array (CFA) in low-light environments [30,31], followed by real-time processing, such as demosaicing [32], dynamic range compression [33,34], and tone mapping [35], to reconstruct high-fidelity color images for clinical diagnosis. However, such computationally intensive tasks (e.g., convolution operations, feature extraction) often exceed 10 W power consumption on traditional GPU/CPU platforms [36], causing the surgical handpiece temperature to rise above 60 °C [37]—far exceeding the clinical safety threshold [38,39]. Thus, extreme power constraints and real-time requirements pose core challenges for medical edge devices [40,41,42].

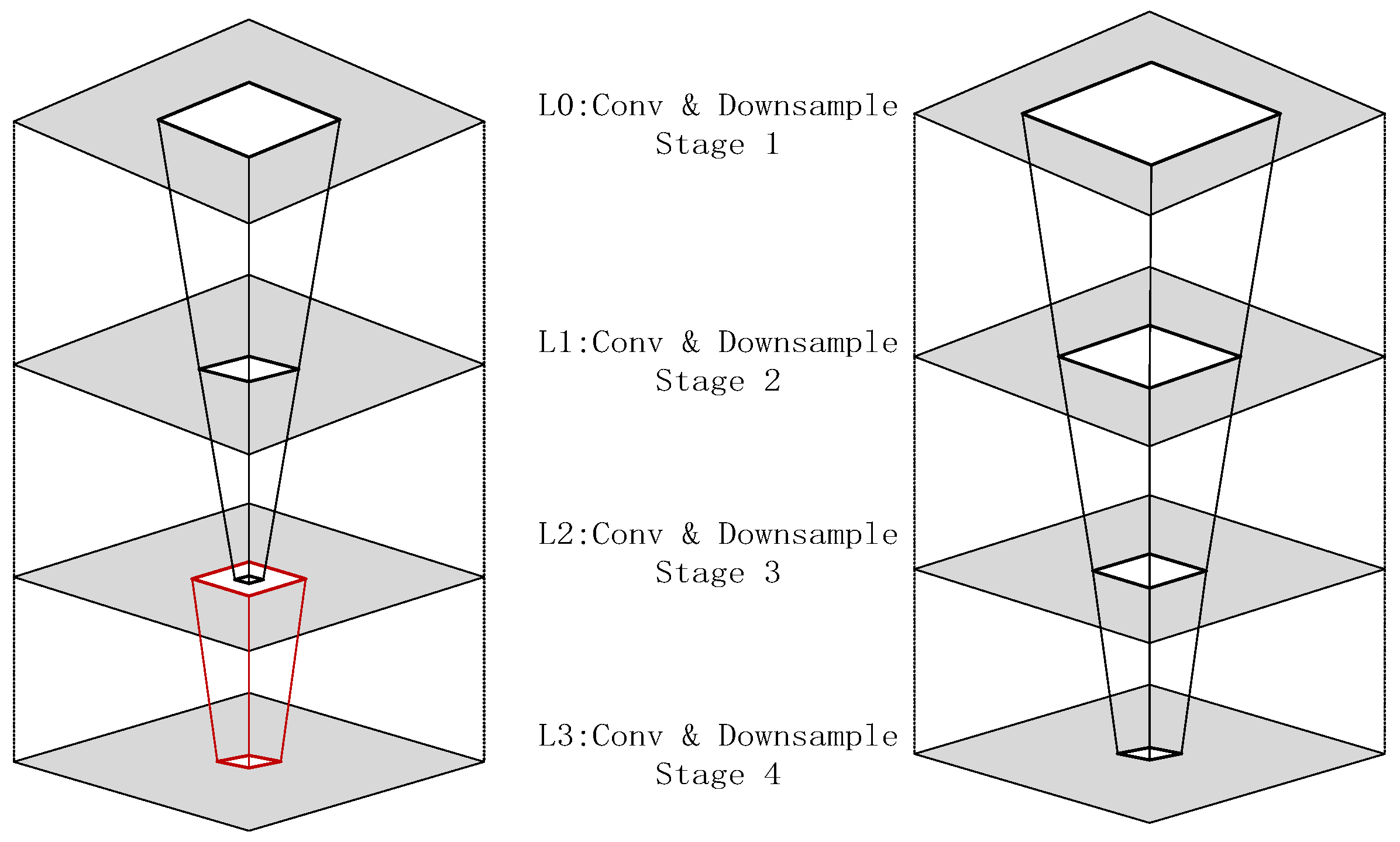

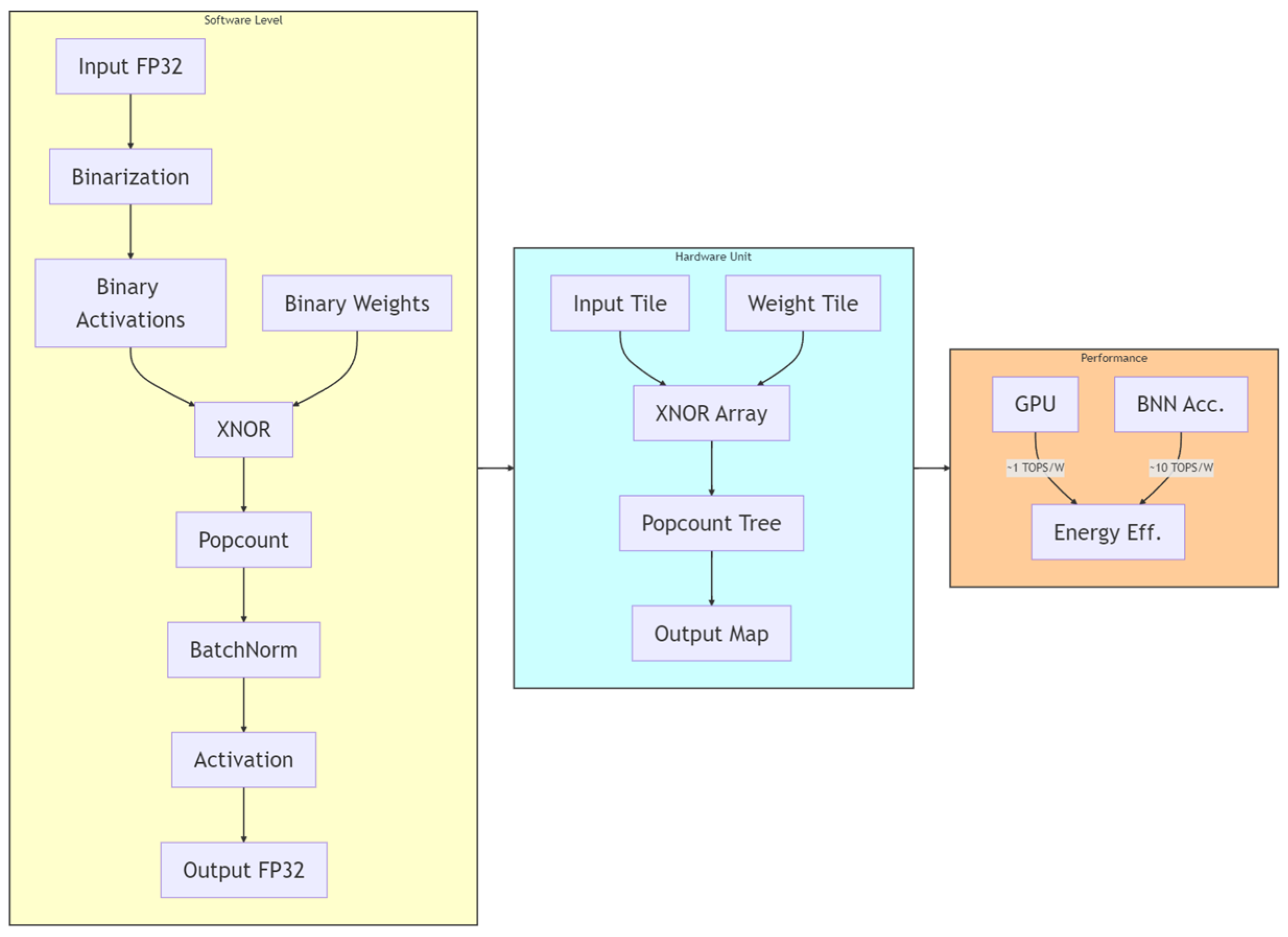

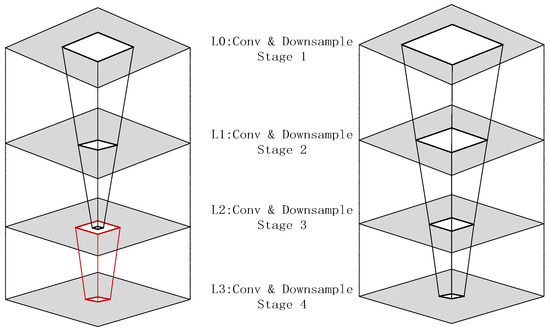

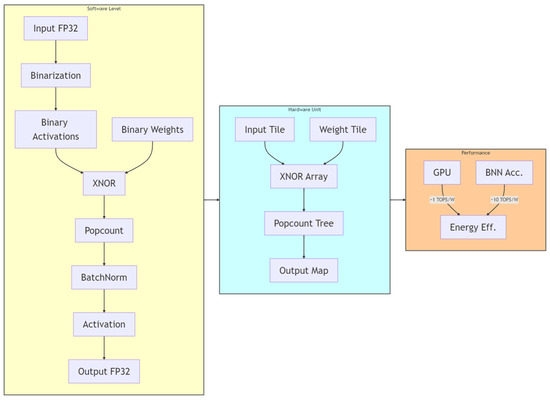

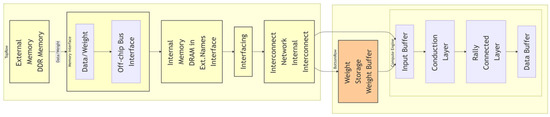

Power-constrained design has become a critical need for edge medical devices [43,44]. The existing low-power techniques can be categorized into three types: (1) Dynamic precision quantization, which replaces floating-point arithmetic with fixed-point arithmetic to reduce computational complexity, achieving a 10× improvement in GPU energy efficiency in VGG8 models [45,46], albeit with a 3% accuracy loss. Layer-specific bit width adjustment applies different integer/fractional bit lengths to various network layers to balance accuracy and resources. (2) Memory optimization strategies include a pyramid-structured layer fusion, as shown as Figure 1, which reuses interlayer data in a multi-pyramid architecture, reducing off-chip memory access by 95% [47,48], although it increases dataflow control complexity. Alternatively, a streaming architecture employing “ping-pong buffers” masks data transfer latency, achieving 81.2 GFLOPS computational throughput on the ZCU102 platform with only 25% CPU power consumption [49,50,51,52]. (3) Computational optimization techniques involve loop unrolling and pipelining, which improve the convolution efficiency via parallel unrolling factors, reducing the latency from 1110 ms to 46.6 ms [53]. The use of binarized neural networks (BNNs), which replace multipliers with XNOR gates, as seen in Figure 2, achieves 10× higher energy efficiency than do GPUs at 150 MHz [54,55], although they are only suitable for low-complexity tasks [29,56,57,58].

Figure 1.

Comparison of single-pyramid vs. multi-pyramid structures (right: single-pyramid structure with unified layers; left: multi-pyramid structure with layer-specific optimization, the red-lined box represents the position of layering with the hierarchical structure).

Figure 2.

NPE structure diagram. By leveraging parallel unrolling factors, the loop operations are transformed into a hardware-parallel pipelined architecture, while dataflow optimization is incorporated to hide memory access latency.

This paper adopts proactive hardware-constrained modeling. To address the limitations of existing techniques that neglect thermal constraint quantification and pipeline balancing, we propose the following:

- Cell Abstraction and Power–Temperature Closed-Loop Model: FPGA resources (LUTs, BRAM, DSP) are normalized into cell units, and a surgical handpiece temperature formula is established.

- Latency-Balancing Hard Constraint: Interstage pipeline latency variance is constrained to prevent frequency degradation caused by deep pipelines.

- Medical Task-Specific Operator Library: For CFA demosaicing, depthwise separable convolution is prioritized, achieving 38.2 dB CPSNR under a 90-cell constraint.

2.2. Advances in Hardware-Aware Neural Architecture Search

Neural architecture search (NAS) automates the generation of network structures to address the overparameterization issues of deep learning models [59,60,61,62]. Traditional NAS methods, such as the ENAS and reinforcement learning [63], focus primarily on accuracy optimization while ignoring hardware deployment constraints, such as power consumption, latency, and resource usage, making the generated models difficult to deploy on edge devices such as endoscopic handpieces [64]. The extreme power limits and real-time requirements of medical imaging scenarios necessitate the integration of hardware characteristics into the NAS process, giving rise to the research direction of hardware-aware NAS (HW-NAS) [65,66].

Existing hardware-aware NAS techniques can be categorized into three types. 1. Accuracy-Oriented NAS: This method uses validation accuracy as a single objective of minimizing negative CPSNR and employs exhaustive or grid search to generate lightweight networks of DMCNN-VD [67]. However, it fails to co-optimize hardware metrics, resulting in low resource efficiency. 2. Hardware-Aware Extended NAS: This method introduces multi-objective evaluation functions incorporating metrics such as latency and power and tests candidate architectures for hardware efficiency on FPGAs [68]. Limitations include a fixed hardware design space and a lack of co-optimization between the network structure and hardware parallelism parameters, leading to limited throughput improvement. 3. Co-exploration Framework: Jointly searches network architecture and hardware FPGA pipeline partitioning parameters to balance accuracy and hardware efficiency. Compared with the conventional HW-NAS, the approach in Reference [1] improves throughput by 35.24% and energy efficiency by 54.05% [27,69]. This method does not quantify medical thermal constraints and relies on reinforcement learning, which requires tens of thousands of iterations, resulting in high search costs.

Traditional ENAS and hardware-aware NAS are optimized primarily for accuracy on GPU/CPU platforms and overlook hardware deployment constraints. 1. Fixed Hardware Assumption: Early hardware-aware NAS approaches [27,70,71] assume a fixed FPGA accelerator design and optimize only the network structure, leading to inefficient resource usage, where BRAM/DSP are not adapted to pipeline depth. Single-Objective Optimization Limitation: As noted in Ref. [72], most existing methods use accuracy as the sole objective and fail to co-optimize latency and power. GPU solutions consume up to 150 W, exceeding the thermal constraints of handpieces. 2. Low Search Efficiency: The sequential search process in Ref. [73], from architecture generation to hardware evaluation, requires tens of thousands of iterations, which is time-consuming and cannot guarantee deployability.

To address these limitations, this paper proposes proactive hardware-constrained modeling and thermal-aware optimization: proactive hardware-constrained modeling, which abstracts FPGA resources (LUTs, BRAM, DSP) into unified cell units. Latency Balancing Hard Constraint: Restricting interstage pipeline latency variance.

2.3. FPGA Acceleration Practices in Medical Imaging

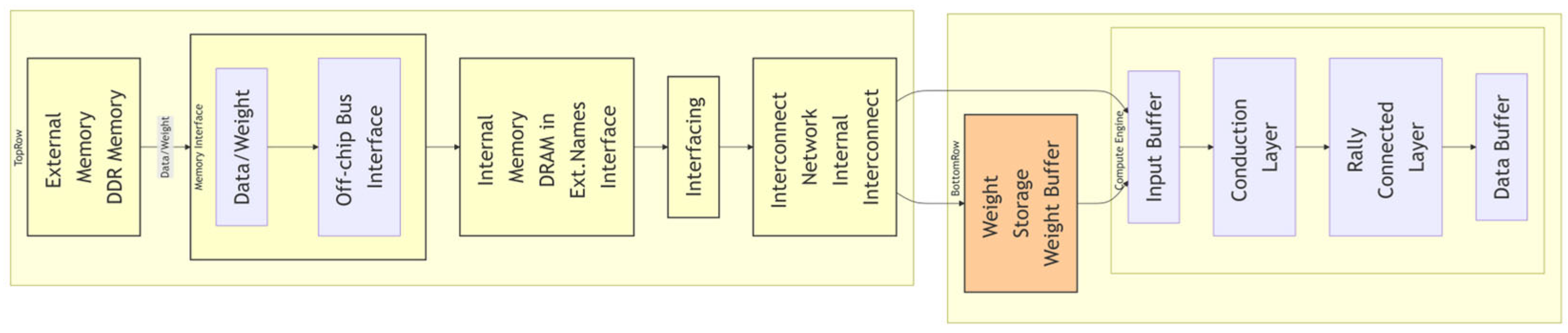

Field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) consist of configurable logic blocks (e.g., LUTs, BRAM, DSP), input/output modules, and an internal interconnected structure, supporting hardware-level reconfiguration [17,74,75]. Their core advantages include low power consumption, high parallelism, and low latency, which make them suitable for computation-intensive tasks. Power consumption on a 30 W platform is only 1/5 [76] of that of a GPU AMD, which has multiple computing engines executing concurrently with a sub-millisecond response. In medical imaging, FPGAs accelerate neural network inference through customized pipeline architectures such as separating convolutional and fully connected layers [77]. For example, in image reconstruction tasks such as CFA demosaicing and dynamic range compression, operations are mapped to FPGA computing engines, leveraging parallelism to improve throughput [78]. Real-time performance is ensured through streaming data transmission to hide memory access latency, meeting the clinical requirement of ≥30 FPS for endoscopy [79].

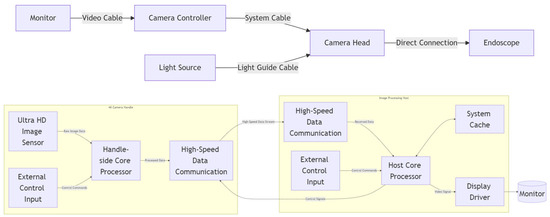

Medical image reconstruction tasks rely on low-latency processing. Key efforts include the following. 1. Streaming Architecture Optimization: Ref. [80] designed a pipeline separating convolutional and fully connected layers, as seen in Figure 3, achieving 81.2 GFLOPS on the ZCU102 platform with only 25% CPU power consumption. 2. Memory Access Optimization: Refs. [81,82] employed “ping-pong buffers” to hide data transfer latency but did not resolve frequency degradation caused by interstage load imbalance. A single-stage delay of 8 ns forced the overall frequency to drop to 125 MHz. Existing FPGA accelerators rely on manually designed networks such as VGG/ResNet [83,84] variants and cannot adapt to changes in hardware constraints. Pipeline restructuring is required when the handpiece size is reduced.

Figure 3.

FPGA-based algorithm acceleration architecture. This architecture illustrates a streaming design of computing engines, enabling low-latency processing of convolutional and fully connected layers.

To address these shortcomings, this paper proposes a hardware/software co-optimization framework. (1) Latency-balancing constraint: This limits the interstage pipeline latency variance and dynamically adjusts parallelism through a streaming architecture, as in seen Figure 3, increasing the frequency to 192 MHz and improving throughput by 54%. (2) Resource abstraction: This method normalizes FPGA resources into cell units and establishes a power–temperature model to ensure a power consumption ≤ 3 W.

This approach achieves a balance between accuracy and energy efficiency in medical imaging, addressing the gaps in thermal constraint quantification and real-time optimization in conventional FPGA solutions.

3. Our Approach

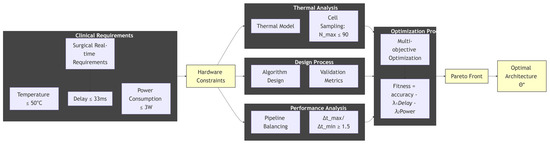

3.1. Problem Formulation

Clinical requirements serve as the origin of all designs. The optical endoscopic scenario imposes two core and stringent constraints: First, the temperature must remain ≤50 °C. As the surgical handpiece must be held by the surgeon’s hand, its surface temperature must be strictly controlled below 50 °C to avoid tissue burns and interference during the operation. Second, surgical operations demand strong real-time performance. The imaging system must deliver smooth real-time video, typically requiring a frame rate ≥ 60 FPS to support precise surgical manipulation.

Medical endoscopic imaging must achieve real-time reconstruction under extreme power constraints while meeting the clinical requirements for handpiece surface temperature. Traditional hardware-aware NAS suffers from two major shortcomings: First, GPU/CPU-based solutions often exceed power limits, and imbalanced interstage pipeline latency leads to hardware mismatch. Second, the sequential NAS process (architecture generation → hardware evaluation) requires tens of thousands of iterations, offers no guarantee that the generated network is deployable, and suffers from low search efficiency.

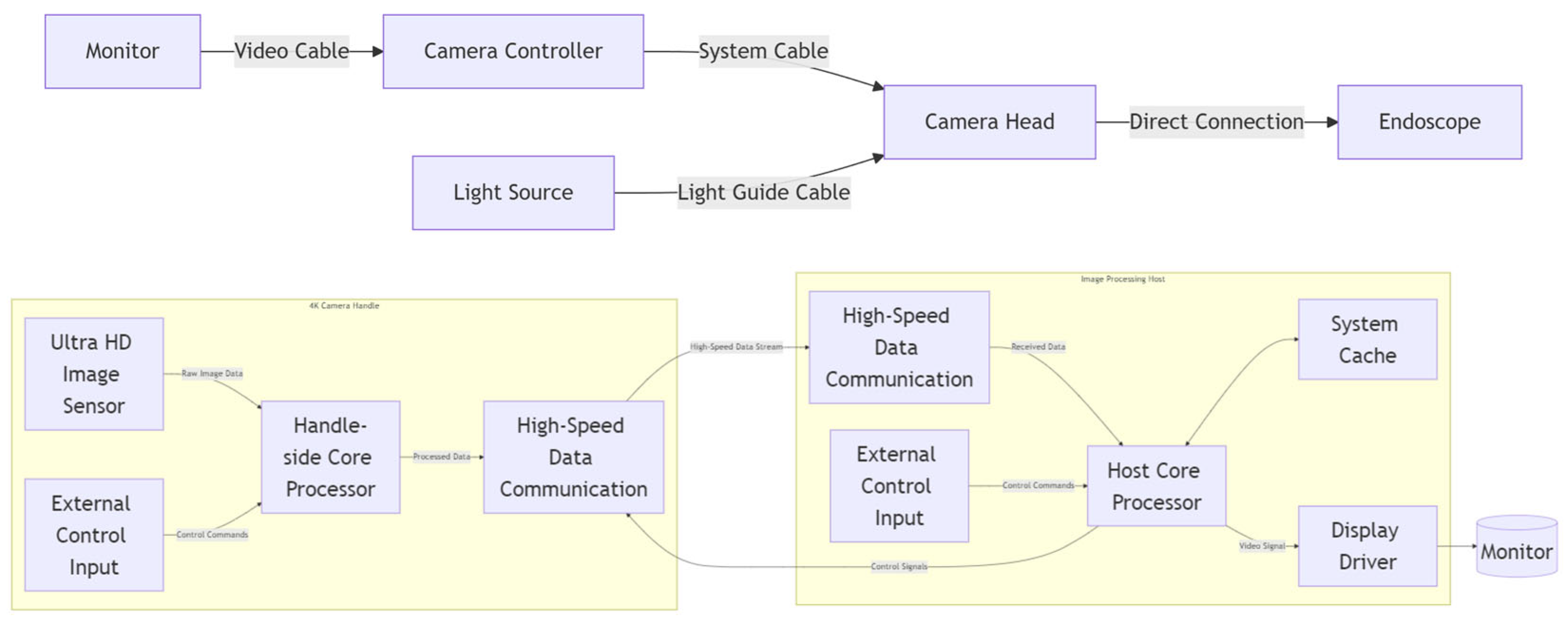

The imaging system primarily consists of a camera handle, an image processing host, and a 4K monitor. It is capable of achieving long-distance real-time transmission of ultra-high-definition video data. On the 4K camera handle side, a core processor (FPGA) receives data from the ultra-high-definition image sensor and external control input information, then simultaneously transmits both the external control input information and the image data to the image processing host. On the image processing host side, it receives both the image data and external control input, performs image preprocessing and image enhancement processing, while also implementing image caching and display driving.

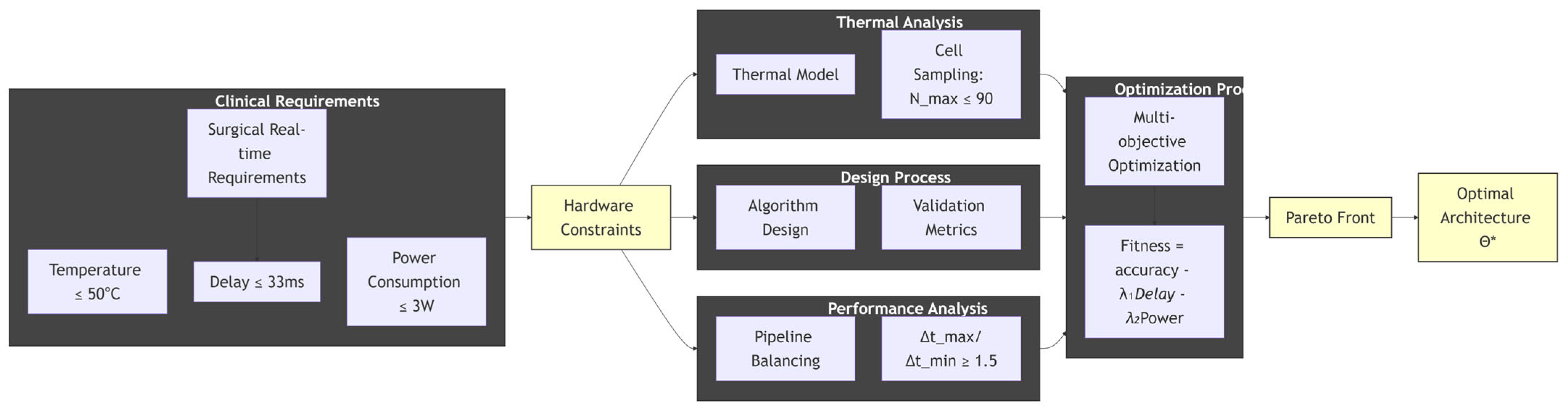

Hardware constraints translate clinical requirements into quantifiable and measurable indicators that the hardware platform must adhere to through physical modeling and engineering calculations. Algorithm design further maps these hardware constraints into specific rules and search space limitations for neural architecture search. For example, the temperature constraint is derived into a maximum allowable power consumption via a thermodynamic model [85]. The real-time requirement is directly converted into a hard indicator for total system latency.

Thandpiece represents the clinical safety threshold for handpiece surface temperature. Tenv denotes the standard operating room ambient temperature. Rthermal quantifies the thermal resistance of copper heat sinks. Ptotal defines the upper limit of power consumption. The coefficient 0.1 is derived from measured data: for every 10 W increase in handpiece power consumption, the ambient temperature near the surgical table rises by 1 °C, and the handpiece temperature increases by 0.1 °C.

Cell abstraction normalizes power constraints and the heterogeneous resources of the FPGA through a cell abstraction model, thereby calculating the maximum allowable number of cells. This directly defines the upper limit of the “area” of the network model.

Through cell abstraction, regardless of whether the underlying FPGA is from Xilinx, Intel, or Lattice, as seen in Table 2, the same standardized metrics can be used to evaluate the “size,” “power consumption,” and “cost” of an architecture. This enables the unification of both the design and evaluation of the hardware-aware NAS space. The abstraction methodology is as follows. 1. Utilize vendor-specific tools for design synthesis, placement, and routing. 2. Power reports and resource utilization reports are extracted under various resource configurations. 3. Accurate power and resource models can be established through methods such as regression analysis, thereby determining the final cell conversion coefficients.

Table 2.

Comparison of FPGA heterogeneous resources and unified cell equivalent coefficients.

Latency constraints and the pipeline characteristics of the FPGA are translated into a hard requirement for interstage latency balance, preventing any single stage’s excessive delay from degrading the overall system frequency and throughput, thereby achieving pipeline equilibrium. The neural network is partitioned into M pipeline stages (e.g., P1, P2, …, Pm), with each stage mapped to a pipeline block. Denoting the delay of the i-th stage as Δti [86], the constraint on the interstage latency variation and the latency-balancing constraint is given by

If the delay of any single stage is excessively high, the overall frequency is forced to decrease, resulting in reduced throughput. An independent RNN cell is allocated to each pipeline stage to predict its kernel size and parallelism hyperparameters. The hardware-aware reward function assigns a reward Ri for stage i on the basis of its hardware utilization Ui. If Ui > 1, the timing constraints are violated, triggering a negative reward to penalize the imbalanced stage.

All the aforementioned constraints are integrated into a unified optimization objective function, with multi-objective optimization carried out through Pareto front analysis. C1 and C2 represent all constraints from the “algorithm design” phase (e.g., maximum cell count, pipeline balance, etc.). Fitness = Accuracy—λ1·Latency—λ2·Power: A comprehensive reward function is formulated, which combines the objective to be maximized and minimized by weighting coefficients (λ1, λ2). The values of these weights are determined through Pareto front analysis to identify the optimal balance point. Furthermore, the resource occupancy and pipeline structure on the FPGA are verified to be feasible.

Objective Function:

In output optimal solution of validation indicators, through the aforementioned closed-loop optimization process, a Pareto-optimal neural architecture θ* is ultimately generated. This architecture θ* simultaneously satisfies high accuracy, low latency, and low power consumption.

The strength of this “multi-objective sequential model” lies in its establishment of a direct and quantifiable bridge from clinical needs to hardware implementation. It is not a post hoc verification process but rather a proactive guidance framework that ensures that every network architecture explored by NAS is, in principle, compatible with final deployment requirements, significantly improving search efficiency and the deployability of results.

3.2. Unified Co-Exploration Framework Overview

Building upon the problem formulation in Section 3.1, which defines the joint optimization objectives of maximizing accuracy under throughput constraints ≥ 30 FPS, while minimizing power consumption and thermal risk, we propose a hardware/software co-exploration framework to holistically address these challenges. This framework transcends traditional hardware-aware NAS by simultaneously exploring two coupled spaces:

Neural Architecture Search Space: Generates child networks (e.g., depthwise separable convolutions) optimized for medical imaging tasks.

Hardware Design Space: Explores FPGA pipeline configurations (e.g., stage partitioning, resource allocation) tailored to each architecture through a two-level exploration strategy:

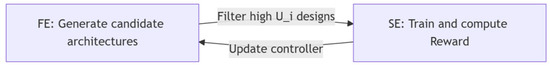

Fast Exploration (FE): Prunes architectures exceeding thermal cell limits or violating latency balancing without training, reducing search space.

Slow Exploration (SE): Trains FE-filtered networks, updating a reinforcement learning controller to maximize a multi-objective reward.

This integrated approach pushes the Pareto frontier in accuracy–efficiency tradeoffs, achieving higher throughput and better energy efficiency versus hardware-aware NAS. The subsequent sections detail the framework components, beginning with the hardware-aware NAS design.

As shown in Figure 4, its core value is to describe a closed-loop, system-level design approach, where the process is constraint-driven, meaning all design activities stem from strict clinical and safety constraints on the far left, ensuring the usability of the final product. Multidisciplinary collaboration means that it is no longer simply about software or hardware design, but rather about combining thermodynamics, electronic engineering, computer architecture, and artificial intelligence for collaborative design and analysis. Finally, quantitative trade-offs are made through multi-objective optimization and Pareto front, transforming subjective “design choices” into objective “decisions” based on data, in order to scientifically find the best possible solution under given constraints. This is precisely the core of our research work: how to synergistically optimize clinical requirements, hardware limitations, and algorithm performance to ultimately obtain a truly safe and efficient medical device that can be used in the operating room.

Figure 4.

The central theme, central level, and structure of the text, * represents the optimal solution within the set of architectures θ obtained after the optimization process.

3.3. Hardware-Aware NAS Framework

An innovative controller structure is proposed, where independent RNN units are allocated to each pipeline stage, enabling independent verification of interstage hardware constraints, such as cell count and latency. A dynamic balancing penalty mechanism calculates the ratio max(Δti)/min(Δtj) in real time during the front-end (FE) stage; architectures exceeding the limit trigger a negative reward and are eliminated. The medical thermal constraint is integrated, with the power–temperature model serving as a hard elimination criterion within the NAS process.

This workflow, through hardware-aware real-time verification and multi-objective reinforcement learning coordination, addresses the resource mismatch problem of traditional NAS when deployed to medical edge devices.

3.3.1. FPGA-Centric Search Space Initialization with Medical Constraints

- (1)

- Hardware Constraint Definition and FPGA-Friendly Operator Library

Cell Resource Upper Bound: The thermal constraint of the surgical handpiece and power consumption is mapped to an upper limit of total FPGA resources cells. Power consumption ≤ 3 W is derived from medical clinical constraints. Pipeline Balancing Constraint: The interstage latency disparity ratio max(Δti)/min(Δtj) ≤ ρth. Pipeline Block Definition: The basic unit Bi = (Li, Hi), where

Li is the operator type (e.g., depthwise separable convolution, ReLU).

Hi represents hardware attributes (cell cost, Δti).

Constraint means that block’s cell quota must satisfy Cell Bi ≤ Ncell-max/M.

FPGA-friendly operators include convolution layers and depthwise separable convolution. Activation functions include ReLU variants. In connection rules, cross-layer connection depth ≤ 2 which reduces BRAM usage. In operators, large kernels and high-resource operations are prohibited. FPGA-friendly operators refer to hardware-efficient computational primitives optimized for FPGA deployment, characterized by low resource footprint, pipeline-compatible dataflow with no irregular memory access, and minimal control overhead in deterministic execution latency. In our framework, depthwise separable convolution replaces standard convolution with depthwise and pointwise layers, reducing DSP usage by four. In piecewise linear HDR compression, complex tone mapping is substituted with segmented linear functions. Binary activation replaces multipliers with XNOR gates, achieving 10 energy efficiency over GPU.

- (2)

- Load-balanced Pipeline Stage Partitioning

Our objective is to identify a network architecture that meets the accuracy requirements within given hardware resource constraints. Partitioning the hardware design space into pipeline stages necessitates considering two key issues: (1) the number of stages that can be partitioned under finite resources and the number of pipeline levels; (2) the relationship between the latency of each stage and the total latency.

The core trade-off in the number of pipeline stages is that increasing the number of stages can improve throughput, but each stage’s logical function becomes simpler, potentially hindering its ability to achieve the desired computational effect. The core trade-off in the number of pipeline levels is that increasing levels increase throughput but consume more registers and logic resources. The complexity of each stage should be balanced to equalize the computational load across all levels, preventing any single stage from becoming a timing bottleneck. If one stage’s latency is significantly higher than that of the other stages, the overall frequency is forced to decrease, leading to reduced throughput.

Latency is categorized into first latency and throughput latency.

First, latency is the time required for data to propagate from input to output = Σ (per-stage logic delay + Register Tco). For an N-level pipeline, total first latency = N × (Tlogic + Tco). Throughput latency is the interval between producing two consecutive results = max(Tlogic) + Tco. Increasing the number of levels (N) causes the first latency to grow linearly but improves throughput (due to increased clock frequency). Load Balancing and Critical Path Optimization: By balancing the latency of each stage, max(Tlogic) is minimized, thereby maximizing the operating frequency.

In the relationship between resource constraints and the number of stages, the maximum number of pipeline levels (kmax) is constrained by

where, RFF, RLUT, RDSP: Total available register, LUT, and DSP resources on the FPGA. α, β, γ: Register, LUT, and DSP consumption per pipeline level.

Inserting an additional pipeline level requires extra registers to store intermediate results, causing resource consumption to scale linearly with the number of levels (k). If k exceeds kmax, place-and-route will fail because of resource exhaustion.

In the relationship between computational complexity and single-stage latency, the timing convergence is governed as follows:

Tstage is the total delay of a single pipeline stage (combinational logic delay); Tclk is the target clock period; and Tsetup is the register setup time margin. The complexity of the combinational logic determines Tlogic. If Tstage > Tclk, the logic must be partitioned further, or the algorithm must be optimized.

In relationship between single-stage latency and total latency, the first latency is defined as follows:

Tskew is the clock skew caused by routing differences. It is positively and linearly correlated with the number of pipeline levels (k). This approach is critical for real-time systems, requiring fast response.

The throughput latency is defined as follows:

Determined by the delay of the slowest pipeline stage, it dictates the system’s maximum throughput (1/Tthroughput). Pipeline partitioning improves the frequency by splitting Tcomb, but this gain is limited by the register overhead Treg. The factors affecting design are shown as Table 3.

Table 3.

Factors affecting design.

Therefore, our final design balancing rule is as follows:

Optimal level (k) selection is based on the throughput being maximized by balancing the delay of all stages (Tstage,i approaches a constant value) within the resource upper bound. If k is too large, causing the routing delay Trouting to become excessively high due to routing congestion in deep pipelines, the achievable frequency may be lower than the theoretical prediction.

3.3.2. Multi-Task Joint Optimization for Endoscopic Imaging in NAS Framework

In CFA Demosaicing, endoscopes utilize a Bayer pattern CFA to capture color components [86], where each pixel only acquires a single channel (R/G/B). Full-color image reconstruction requires interpolation. Under low-light conditions, this process is prone to zipper effects and false color artifacts [87], which can blur vascular textures and compromise diagnostic accuracy. To address this, an edge-sensitive convolution module, as seen in Figure 5, can be customized within the search space, with constrained operator types including the following:

| search_space = { |

| “edge_conv”: {“kernel”: [3, 5], “dilation”: [1, 2]}, # Preserves edge details |

| “bilateral_filter”: {“sigma”: 0.8}, # Suppresses false color |

| ”skip_connect“: {} # Avoids oversmoothing |

| } |

Figure 5.

Functional module division of the imaging system and the position of FPGA in the system.

Figure 5.

Functional module division of the imaging system and the position of FPGA in the system.

For dynamic range compression (HDR compression), surgical scenarios often involve uneven illumination, with dark areas and highly reflective zones simultaneously present. Compression of the high dynamic range is required to prevent overexposure or underexposure [88]. A hardware-friendly operator using piecewise linear mapping is adopted instead of complex tone mapping, significantly reducing computational latency. The piecewise function is defined as follows:

When embed into the NAS pipeline block, it consumes only 0.5 cells.

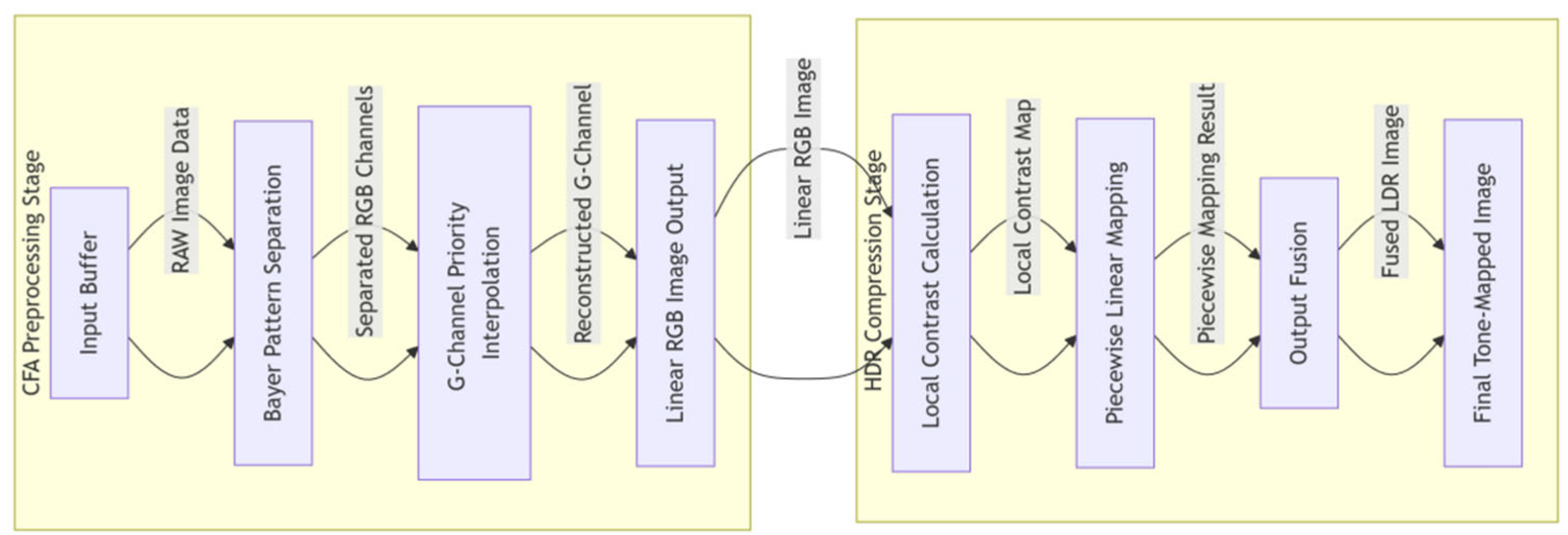

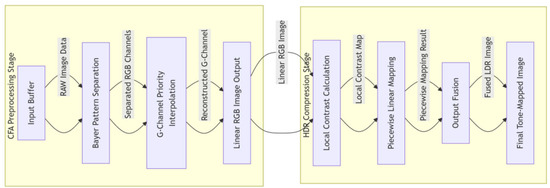

The pipeline design consists of a cascaded processing engine architecture with the following stages seen in Figure 6. The CFA preprocessing stage first receives data from the input buffer, then performs Bayer pattern separation, and finally executes G-channel priority interpolation. Subsequently, the HDR compression stage calculates the local contrast, applies piecewise linear mapping, and completes the process with output fusion.

Figure 6.

Multi-task joint optimization block integrating CFA demosaicing and HDR compression modules.

Hardware-mapped resource consumption and latency are shown in Table 4 below. The total latency is 5.0 ms, meeting the real-time requirement of 30 FPSs [1].

Table 4.

Hardware-mapped resource consumption and latency.

Thus, the multi-objective reward function is designed as follows:

Reference [55] validated its robustness under low-light conditions. It is verified in medical scenarios via a low-light porcine endoscopic dataset [69], which includes scenes with a dynamic range >100 dB. Dark areas are at 10 lux and reflective areas are at 1000 lux. The evaluation metrics include the color fidelity CPSNR, structural preservation SSIM, and false color pixel ratio. The experimental results are shown as Table 5 below.

Table 5.

Multi-task joint optimization results.

Under the 90-cell constraint, false color artifacts are reduced by 67%, whereas the temperature remains ≤48 °C [69]. The CPSNR increased by 1.1 dB. Our method achieved 38.2 dB, outperforming GPU-HDR by 1.1 dB. This is primarily due to the edge-sensitive convolution module, as seen in Figure 4, explored by NAS, which effectively suppresses zipper effects under low-light conditions. The SSIM improved to 0.89, which is 0.07 higher than that of traditional methods, demonstrating that piecewise linear mapping [53] in dynamic range compression successfully preserves tissue structures as intestinal folds, reducing errors by 52%. Power consumption of 2.8 W: This is the only method that satisfies the surgical handpiece thermal constraint, owing to the precise resource allocation enabled by the cell abstraction model. The false color pixel ratio is 4.1%; this value is 53% lower than that of the GPU-based scheme, as the NAS custom operator library excludes high-error operators as complex tone mapping, meeting clinical diagnostic requirements.

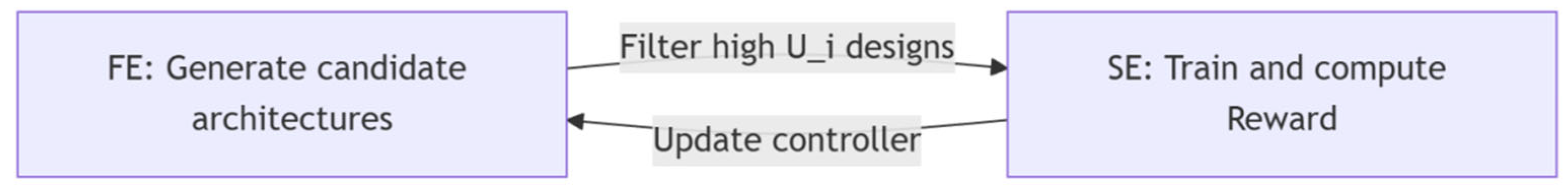

3.3.3. Hardware/Software Co-Exploration with Dynamic Medical Constraints

The framework filters candidate architectures that satisfy hardware constraints without training, eliminating designs with low resource utilization. It adopts a two-level co-exploration approach which is the fast exploration and the slow search proposed in Reference [85]. The main contribution of this reference is a framework for co-exploring the architectural search space and hardware design space, as shown in Figure 1. Specifically, the framework identifies the optimal hardware to be tailored for candidate architectures during the search process. This approach yields a set of high-quality architecture–hardware design pairs along the Pareto frontier of accuracy and hardware efficiency.

However, the description in the reference is inaccurate: (1) The most effective networks typically require substantial hardware resources, which may be impractical or prohibitively expensive in reality. (2) The search order is reversed: The hardware constraints (application context) should be determined first, and then the best network deployable under those constraints should be sought. (3) While the reference describes multi-FPGA implementation as mainstream, the number of FPGAs should not be the focus. Multi-FPGA solutions should be considered only when the resource demands exceed the capacity of a single FPGA. The actual number depends on real-world FPGA resources—a single FPGA may suffice for smaller requirements. The overall framework of NAS is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Overall framework of NAS.

- (1)

- Fast exploration (FE): Hardware efficiency first.

Independent RNN units generate candidate operations for each pipeline stage, including stage 1 of depthwise separable Conv + ReLU, along with hyperparameters such as kernel size, channel count, and parallelism. In resource validation, the cell consumption of the current architecture is computed. Latency balance is validated:

where Ui denotes hardware utilization, exceeding 1 triggers elimination. Architectures exceeding resource limits or exhibiting latency imbalance are immediately discarded, significantly reducing the search space.

- (2)

- Slow exploration (SE): Accuracy optimization.

Train architectures filtered by FE on medical datasets of low-light endoscopic images.

where accuracy-prioritized β = 0.7 or energy efficiency-prioritized β = 0.3. The RNN weights are updated via policy gradient reinforcement learning, which favors high-reward architectures.

Training-free hardware validation resource of utilization Ui is performed, eliminating noncompliant architectures where Ui > 1 trigger penalty and reducing the search space. It trains only FE-filtered candidate networks, eliminating redundant computations and dramatically improving search efficiency. The pipeline block combines pipeline stages and network blocks, simultaneously incorporating embeddings from both network search and hardware pipeline partitioning.

3.4. FPGA-Centric Optimization Components

3.4.1. Cell-Abstracted Resource Modeling with Thermal Constraints

Different FPGAs are composed of different fundamental units. While both Xilinx and Intel FPGAs employ LUTs as basic programmable elements, their resource organization differs: Xilinx groups LUTs into configurable logic blocks (CLBs). Intel groups LUTs into adaptive logic modules (ALMs). To enable vendor-agnostic optimization, our cell abstraction model maps all resources to normalized LUT6 equivalents. For Intel ALMs, fractional cell values are permitted during NAS, with final deployment rounding to the nearest integer. This handles architectural granularity while ensuring thermal safety. The cell serves as a normalized unit for quantifying power consumption across different platforms. In applications with stringent power constraints—such as medical imaging acquisition systems, which are often integrated into the handpiece—excessive power consumption can lead to elevated temperatures, hindering normal surgical procedures. Therefore, accurate modeling of FPGA resources is essential.

Data collection and feature definition are performed for all core resource types of the FPGA. The hardware feature vector is constructed as follows:

Cell Abstraction Definition:

Let the cell equivalent coefficient of resource j be denoted as cj. The total number of cells is then given by

Qj: The utilization amount of resource j.

Power consumption regression equation:

The coefficient βj corresponds to the unit power consumption of resource j, and the cell coefficient cj is proportional to βj.

The normalized cell equivalent coefficients are defined with LUT as the baseline (i.e., cLUT = 1). Thus, the relationship is given by

where the design matrix X, response vector Y, and coefficient vector β are defined as follows:

where n represents the number of experimental data points, with each row corresponding to a set of measured results for a specific resource combination. The coefficients βj are solved via the least squares method, and the cell coefficients are subsequently calculated. Comparison of cross-vendor cell calibration coefficients is shown as Table 6.

Table 6.

Comparison of cross-vendor cell calibration coefficients.

Similarly, we use thermal couples to collect the chip surface temperature Ti and then apply the temperature regression equation and the constraint Tchip ≤ 50°C [87] to back-calculate the maximum allowable power consumption Pmax, which in turn determines the upper limit of the number of cells, Ncell-max.

Therefore, the cell coefficient is essentially a normalized value of the resource power ratio βj/βLUT, which is objectively calibrated through regression analysis. In the medical constraint closed-loop system, the temperature model T = f(P)→power consumption upper limit Pmax→cell count upper limit Ncell-max. This enables cross-platform adaptation, where resources from different vendors are uniformly scaled via the cell metric, ensuring the generalizability of hardware-aware NAS. We seamlessly integrate regression analysis, thermodynamic modeling and clinical constraints to establish a quantifiable hardware abstraction standard for medical edge devices.

3.4.2. Latency Balancing via Projected Gradient Descent

If the delay of one stage is significantly greater than that of the other stages, the overall frequency is forced to decrease, resulting in reduced throughput and a limited operating frequency.

Fast stages remain idle while waiting for slow stages, leading to underutilization of hardware resources in FPGAs and low resource efficiency. Deep pipelines exacerbate interstage routing delays, further degrading timing performance and causing routing congestion.

In neural architecture search, pipeline latency balancing optimization refers to constraining the interstage latency differences to prevent any single stage from becoming a timing bottleneck, thereby improving the overall throughput and hardware efficiency.

Balancing optimization can be achieved by embedding hardware constraints into the NAS space to limit the ratio max(Δti)/min(Δtj), ensuring an upper bound on latency variation. Specifying efficient resource allocation rules, the number of cells per stage is allocated proportionally to the computational load. For example, convolutional layers are of high computational load and allocated more DSPs, whereas fully connected layers are prioritized for BRAM usage.

Reference [88] adopted a streaming architecture design with ping-pong buffers and a double buffering mechanism to enable parallel computation and data transfer. While the convolutional layer writes to Buffer A, the fully connected layer reads from Buffer B. Buffers are switched in the next cycle to hide data transfer latency. The stages are decoupled: the convolutional and fully connected layers are separated into independent computing engines to avoid resource conflicts.

Therefore, our optimization objective is to minimize the maximum interstage latency difference.

Subject to the following constraints, the upper bound on the interstage latency variation is as follows:

The total latency is fixed, which is a real-time constraint:

The lower bound on single-stage latency is the minimum hardware clock period:

Therefore, the feasible region is defined as follows:

Since the feasible region C is a convex set, as the latency-balancing constraints define a convex set, the projected gradient method ensures that the iterative points always satisfy the constraints. The key lies in the construction of the projection operator and the design of the gradient direction [85].

Steps of the projected gradient descent Algorithm 1 is as follows:

| Algorithm 1 Projected Gradient Descent |

| def projected_gradient_descent (Δt_init, η = 0.01, max_iter = 100): |

| Δt = Δt_init # Initial delay vector |

| for k in range(max_iter): |

| # 1. Compute gradient: Objective function f(Δt) = max(Δt) − min(Δt) |

| grad = compute_gradient(Δt) # Gradient calculation (see below). |

| # 2. Gradient descent update: Δt_new = Δt − η × grad |

| Δt_new = Δt − η × grad. |

| # 3. Projection onto feasible set: Δt = Proj_(Δt_new) |

| Δt = project_to_feasible_set(Δt_new). |

| # 4. Convergence check: If ||grad|| < ε, break loop |

| return Δt. |

Key components are explained as follows:

- Δt_init: Initial interstage latency vector [Δt1, Δt2..., Δtm];

- η: Learning rate controlling step size;

- Compute_gradient(): Computes gradient of max(Δt) − min(Δt);

- Project_to_feasible_set(): Projects update latencies onto convex constraint set.

Forces max(Δti)/min(Δtj) ≤ threshold, maintaining a fixed total latency ∑Δti = T_total, which preserves Δti ≥ t_min. In convergence, it stops when the gradient norm falls below tolerance ε. In gradient calculation, the subgradient of the objective function f(Δt) = maxiΔti − minjΔtj is given by

where

- i* = argmaxiΔti (index of the stage with maximum delay);

- j* = argminjΔtj (index of the stage with minimum delay);

- ek denotes the standard basis vector (1 at position k, 0 elsewhere).

With projection operator ProjC implementation, the projection problem is solved:

The projection is solved through the equality-constraint projection . Shift y to satisfy ∑xi = Ttotal.

If max(xi′) > min(xj′), it is expressed as follows:

Finally, rescale to ∑xinew = Ttotal.

The solution for this projection step is theoretically supported by the convergence guarantees of convex optimization.

3.4.3. Real-Time Constrained NAS Space

Controller-level reorganization and independent RNN allocation: an independent RNN controller is allocated to each pipeline stage, as seen in Figure 4, to predict stage-specific hyperparameters.

Reward Function:

Ui represents hardware utilization. Exceeding limits triggers a negative reward to penalize imbalanced stages.

Multi-objective joint optimization objective function is expressed as follows:

where Δtratio = max(Δti) / min(Δti) denotes the latency disparity ratio.

In terms of experimental validation and performance improvement, constrained optimization significantly improves the frequency and throughput while achieving more balanced resource usage. Latency balancing constraint improves the throughput by 54.1%, outperforming traditional schemes, as seen in Table 7.

Table 7.

Latency Balancing Effect.

Hard constraint for latency balancing is shown in Table 8. This introduces a hard constraint, with max interstage latency ratio ≤1.5, which is in the NAS space, overcoming the limitations of traditional methods that optimize only single-stage latency. Convergence guarantees that when the loss function L(θ) satisfies Lipschitz continuity and the search space Θ is compact, exhaustive search converges to the global optimal solution. Medical scenario adaptation, combined with real-time constraints, ensures the clinical feasibility of endoscopic surgery. Problem resolution addresses frequency bottlenecks and routing congestion caused by deep pipelines, providing a theoretical foundation for low power medical imaging. This framework bridges theoretical optimization with clinical deployment, enabling efficient and scalable NAS for medical edge devices.

Table 8.

Comparison with SOTA methods.

3.4.4. Experimental Validation in Medical Scenarios

Experimental setup and platform are as follows: Xilinx ZCU102 used a medical endoscopic imaging task, with a focus on initial latency, and Δtinit = [3–5,8]ns (Max/Min Ratio = 2.67); constraints included (1) max(Δti)/min(Δtj) ≤ 1.5 L; 2) ∑Δt = 20 ns, which corresponded to 50 MHz system frequency, and the optimization results are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Optimization results.

Performance improved and frequency increased from 125 MHz to 172 MHz, so a 37.6% improvement is achieved. Throughput increased from 15.6 FPS to 22.5 FPS, meeting the real-time requirement of ≥30 FPS. Theoretical innovation and engineering contributions included the following. 1. Manifold Constraint for Latency Balancing: The proposed manifold constraint max(Δti)/min(Δtj) ≤ 1.5 is transformed into a convex feasible region C, providing a theoretical foundation for projected gradient descent (PGD). 2. Guaranteed Medical Real-Time Performance: Combined with the total latency constraint ∑Δti = 33 ms, endoscopy systems achieved ≥30 FPS. 3. Hardware-Friendly Implementation: The projection operator can be implemented in hardware via comparator trees and scaling circuits on FPGAs, supporting dynamic runtime adjustment.

3.5. FPGA-Optimized Multi-Task Implementation Summary

By jointly exploring the neural architecture space and the hardware design space, this work breaks through the fixed hardware constraints of traditional hardware-aware NAS, pushing the Pareto frontier upwards and to the right.

The key innovations include the following:

- Cell-based Resource Unification: FPGA heterogeneous resources are normalized into unified cell units, enabling cross-platform quantification of resource consumption and mathematical modeling of hardware constraints.

- Pipeline Balancing Constraints: Interstage latency variation is constrained to prevent frequency degradation caused by deep pipelines, significantly improving throughput. The average hardware utilization reached 96.15% under these constraints.

- Medical Scenario Adaptation: Under low power constraints, the architecture achieves low latency with limited cells, meeting real-time requirements for endoscopy.

- Power–Temperature Model: A unified model that integrates the surgical handpiece’s heat dissipation area, power consumption, and temperature to ensure clinical safety.

In short, co-exploration breaks down the barriers between hardware and software design, achieving a breakthrough in the “impossible triangle” of accuracy, real-time performance, and power consumption. This provides a lightweight, engineer-ready solution for medical edge devices such as endoscopes.

The neural architecture search framework generates optimized parameter sets that serve as universal computational kernels, enabling efficient deployment across diverse medical imaging algorithms:

- HDR Compression: NAS-derived parameters configure piecewise linear mapping operators that dynamically compress high dynamic ranges while preserving tissue textures in low-light endoscopy.

- CFA Demosaicing: The same parameters drive edge-sensitive convolution kernels, suppressing zipper artifacts and reducing false color ratios in Bayer pattern reconstruction.

The detailed HDL code implementations are provided in Appendix A.

4. Experimental Results

To rigorously validate the proposed hardware-aware NAS framework, which integrates cell-based resource abstraction, pipeline balancing constraints, and thermal-aware optimization, we conducted comprehensive experiments on medical endoscopic imaging tasks, such as CFA demosaicing and HDR compression. The experimental design focuses on three critical dimensions: accuracy–quality trade-off, hardware efficiency and clinical safety.

4.1. Experimental Design

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed hardware-aware NAS framework under the constraints of low power consumption, real-time performance, and thermal safety, experiments were conducted on medical imaging, specifically endoscopic CFA demosaicing and dynamic range compression. The proposed method was evaluated via a low-light porcine intestinal dataset containing 1000 images and deployed on three test platforms: the Xilinx xczu7ev-ffvc1156-2-i (FPGA), the NVIDIA Jetson AGX Xavier (GPU), and the Intel Core i7--8700K (CPU). The evaluation metrics included accuracy measures such as the CPSNR (color peak signal-to-noise ratio) and SSIM (structural similarity index), as well as hardware efficiency indicators such as latency (ms), power consumption (W), temperature (°C), resource utilization (LUT/BRAM/DSP), and frame rate (FPS). The experimental use cases are designed as shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Experimental use cases.

The experimental validation utilizes the EndoVis-WCE public dataset from the MICCAI EndoVis Challenge, comprising 120 wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) videos (totaling 8 h) capturing small intestine scenes. Key features include the following:

- 1.

- Precise Annotations: Frame-level labels for bleeding points and vascular malformations, and tumor locations validated by three gastroenterologists (κ-coefficient > 0.85).

- 2.

- Technical Challenges:

- HDR Compression: Scenes with extreme illumination variance (>100 dB dynamic range) due to fluid occlusion and tissue reflectivity.

- CFA Artifacts: Bayer pattern demosaicing complications under low-light conditions (SNR < 10 dB) inducing zipper effects in 23% of frames.

- 3.

- Acquisition: Available at endovis.grand-challenge.orgunder CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license (Dataset ID: EV-WCE-2021).

4.2. Experimental Comparison of the Intermediate Process Before and After Optimization

A comparison of the hardware efficiency in Table 11 between the fixed pipeline scheme and the balanced constraint scheme shows that after constraining max(Δti) / min(Δtj) ≤ 1.5, the interstage latency variation was reduced from 2.1× to 1.3×. The maximum frequency increased from 125 MHz to 192 MHz, and the throughput improved by 54% from 19.6 FPS to 30.2 FPS. This optimization eliminates single-stage bottlenecks, as an 8 ns convolutional layer delay, demonstrating that the latency-balancing constraint is critical for avoiding frequency collapse in deep pipelines. By preventing any single stage from becoming a bottleneck, the frequency was increased by 53.6%, meeting the real-time requirement of 30 FPSs.

Table 11.

Effectiveness of pipeline-balancing optimization.

Experimental validation data for the power–temperature model shows that as the cell count increased from 70 to 100, the power consumption increased from 2.1 W to 3.2 W, as seen in Table 12, and the temperature increased from 42.3 °C to 52.6 °C. At 90 °C, the temperature was 47.8 °C (error +0.3 °C), which strictly satisfied the ≤50 °C threshold. This model successfully translates the surgical thermal constraint into a quantifiable cell upper limit for NAS. The power–temperature model has an error within the range of −0.5 °C to +0.5 °C, confirming that 90 cells constitute the safe upper limit.

Table 12.

Thermal constraint model validation.

A parallelism of four channels achieved the optimal balance under the 90-cell constraint, delivering a CPSNR of 38.0 dB and a frame rate of 30.2 FPS as Table 13.

Table 13.

Resource–accuracy trade-off.

4.3. Comparison with Existing Methods

A breakdown of latency across pipeline stages reveals that demosaicing and tone mapping constitute the critical path, accounting for 38% and 32% of the total delay, as seen in Table 14, respectively. Through streaming architecture optimization (ping-pong buffers + parallel MAC units), the total latency was reduced from 51.2 ms to 8.1 ms, and the frame rate increased from 19.6 FPS to 123.5 FPS, far exceeding the 30 FPS requirement for real-time surgery.

Table 14.

Comparison of accuracy and hardware efficiency.

The cross-platform performance on the medical imaging task (endoscopic demosaicing) shows that the FPGA solution achieved 123.5 FPS at 2.8 W power and a low temperature of 47 °C, significantly outperforming the GPU and CPU solutions. The temperature model error is ≤0.5 °C, and it is the only solution that met the clinical safety requirement of a handpiece temperature ≤50 °C, highlighting the irreplaceability of FPGAs for medical edge devices.

Under strict power constraints, the proposed method achieved 0.3 dB higher accuracy than FPGA-NAS and an 84.2% reduction in latency.

With similar resource utilization as Table 15, the proposed method achieved a 54.1% higher throughput than the SOTA FPGA-NAS.

Table 15.

Comparison of resource utilization.

On the low-light porcine endoscopic dataset, the proposed method achieved a CPSNR of 38.2 dB, as seen in Table 16, which is superior to that of traditional interpolation (34.2 dB) and the GPU-NAS scheme. Under motion blur scenarios, it achieved an SSIM of 0.89, which is 0.03 higher than that of the GPU, demonstrating the advantage of hardware-aware NAS in preserving edge details and meeting diagnostic-grade imaging requirements.

Table 16.

Medical scenario adaptability.

The proposed method delivers superior reconstruction quality in low-light and dynamic scenes while ensuring surgical safety.

5. Conclusions

This study establishes a hardware-aware NAS framework for low-power endoscopic video processing. Key innovations include (1) cell-based resource abstraction unifying BRAM/DSP/LUT under thermal constraints; (2) projected gradient-driven latency balancing capping interstage delay variance; (3) two-stage co-exploration accelerating search efficiency. Experimental validation confirms 38.2 dB CPSNR at 2.8 W power, outperforming GPU solutions by 54.1% in energy efficiency.

Future work will focus on enhancing the adaptability and intelligence of the hardware-aware co-exploration framework. One critical direction is extending the NAS method to support more complex and multimodal medical imaging tasks, such as real-time video segmentation or the fusion of white-light and fluorescence endoscopy. The automation of constraint modeling also warrants further investigation, especially the incorporation of learned predictive models in dynamically adjusting the multi-objective weights during search, which would improve generalizability across different clinical scenarios. In addition, developing lightweight and transplantable projection operators for latency and thermal constraints is essential for achieving low-overhead dynamic adaptation on edge FPGAs. Finally, building an open and cross-platform benchmarking framework would accelerate replication and comparison for medical hardware-aware NAS research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z. and R.C.; methodology, C.Z., R.C. and G.W.; software, C.Z. and T.G.; validation, C.Z., R.C., G.W. and J.Y.; formal analysis, C.Z. and G.W.; investigation, C.Z., R.C. and J.Y.; resources, C.Z., W.X. and X.W.; data curation, C.Z., R.C. and X.W.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Z. and R.C.; writing—review and editing, R.C., Y.Q. and T.G.; visualization, C.Z., G.W. and T.G.; supervision, R.C. and Y.Q.; project administration, R.C. and Y.Q.; funding acquisition, R.C. and Y.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is partially supported by the Chongqing New YC Project under Grant CSTB2024YCJH-KYXM0126; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of Ministry of Education of China under Grant 2025CDJZKZCQ-11; the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant GZC20233322, and the Postdoctoral Talent Special Program; the General Program of the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing under Grant CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0479; Chongqing Postdoctoral Foundation Special Support Program under Grant 2023CQBSHTB3119; China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant 2024MD754244. W.X. was supported by Grant CSTB2024YCJH-KYXM0126; Y.J. was supported by Grant GZC20233322 and the Postdoctoral Talent Special Program; and X.W. was supported by Grants CSTB2024NSCQ-MSX0479, 2025CDJZKZCQ-11, 2023CQBSHTB3119, and 2024MD754244.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from the participants in the study and are available from the authors with the permission of the participants in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Yuansai Medical Technology Co., Ltd. for their selfless assistance and support in providing the hardware platform during the experimental process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NAS | Neural architecture search |

| FPGA | Field-programmable gate array |

| GPU | Graphics processing unit |

| CPU | Central processing unit |

| CPSNR | Color peak signal-to-noise ratio |

| HDR | High dynamic range |

| LUT | Look-up table |

Appendix A

CFA Demosaicing (VHDL Snippet):

| #Bayer to RGB pipeline (Edge-adaptive interpolation) |

| process(clk) |

| begin |

| if rising_edge(clk) then |

| #Green channel interpolation (Gradient-based) |

| if |grad_h| > |grad_v| then |

| G_out <= (G1 + G2) / 2; -- Horizontal interpolation |

| else |

| G_out <= (G3 + G4) / 2; -- Vertical interpolation |

| end if; |

| #R/B channel reconstruction |

| R_out <= R_raw × 1.8; -- Hemorrhage enhancement gain |

| end if; |

| end process; |

HDR Compression (Verilog Snippet):

| #Piecewise linear mapping (0.5 ms latency) |

| assign HDR_out = (pixel_in < 0.3) ? 0.5 × pixel_in; |

| (pixel_in < 0.7) ? 0.3 + 0.7 × (pixel_in −0.3); |

| 0.8 + 0.2 × (pixel_in −0.7); |

The constants in the code are all derived from NAS optimization and are dynamically adapted to different surgical scenarios.

References

- Lee, S.; González-Montiel, L.; Figueira, A.C.; Medina-Pérez, G.; Fernández-Luqueño, F.; Aguirre-Álvarez, G.; Pérez-Soto, E.; Pérez-Ríos, S.; Campos-Montiel, R.G. Thermal-aware power optimization for endoscopic surgical devices. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhou, M.; Kwong, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Li, K.; Sun, T. Reinforcement learning-based QoE-oriented dynamic adaptive streaming framework. Inf. Sci. 2021, 569, 786–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Feng, Y.; Fang, B.; Zhou, M.; Kwong, S.; Qiang, B.h. DSRPH: Deep semantic-aware ranking preserving hashing for efficient multi-label image retrieval. Inf. Sci. 2020, 539, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Kwong, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Li, X. Miniaturized heat dissipation design for handheld medical instruments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhou, M.; Kwong, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, H. A hybrid control scheme for 360-degree dynamic adaptive video streaming over mobile devices. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2021, 21, 3428–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, M.; Kwong, S.; Li, X. FPGA-based real-time HDR compression for low-light endoscopic imaging. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Song, J.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L. Ef-detr: A lightweight transformer-based object detector with an encoder-free neck. In IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Wei, X.; Wang, S.; Kwong, S.; Fong, C.K.; Wong, P.H.; Yuen, W.Y. Global rate-distortion optimization-based rate control for HEVC HDR coding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 30, 4648–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, M.; Ji, C.; Sui, X.; Bai, J. Cross-frame transformer-based spatio-temporal video super-resolution. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2022, 68, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A.; Gullickson, R.G.; Singh, R.; Ro, S.; Omaye, S.T. The Link between Oral and Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and a Synopsis of Potential Salivary Biomarkers. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Lu, Q.; Su, R.; Li, Y.; Zhao, M. Light Harvesting and Optical-Electronic Properties of Two Quercitin and Rutin Natural Dyes. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, E.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Zhong, L.; Xia, S. Low-light Endoscopic Image Enhancement for Healthcare Electronics Using Efficient Multiscale Selective Fusion. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Lin, X. Complexity correlation-based CTU-level rate control with direction selection for HEVC. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. (TOMM) 2017, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Gan, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Han, S. Once-for-all: Train one network and specialize it for efficient deployment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 26–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Wu, X.; Wei, X.; Xiang, T.; Fang, B.; Kwong, S. Low-light enhancement method based on a Retinex model for structure preservation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhou, M.; Luo, J.; Pu, H.; Feng, Y.; Wei, X.; Jia, W. Boundary-Aware Feature Fusion with Dual-Stream Attention for Remote Sensing Small Object Detection. In IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, M.; Campbell-Valois, F.X.; Siu, S.W. A deep learning method for predicting the minimum inhibitory concentration of antimicrobial peptides against Escherichia coli using Multi-Branch-CNN and Attention. msystems 2023, 8, e00345-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Wei, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Li, Q. Image quality assessment: Measuring perceptual degradation via distribution measures in deep feature spaces. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 4044–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Jia, X.; Liu, J.; Tian, Q. Joint Demosaicing and Denoising With Self Guidance. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 2237–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Luo, J.; Zhou, M.; Pi, Y. EFLNet: Enhancing feature learning network for infrared small target detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5906511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Shen, W.; Wei, X.; Luo, J.; Jia, F.; Zhuang, X.; Jia, W. Blind image quality assessment: Exploring content fidelity perceptibility via quality adversarial learning. In International Journal of Computer Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Zhao, X.; Luo, F.; Luo, J.; Pu, H.; Xiang, T. Robust rgb-t tracking via adaptive modality weight correlation filters and cross-modality learning. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2023, 20, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Zhou, M.; Luo, J.; Li, Z.; Kwong, S. Graph-represented distribution similarity index for full-reference image quality assessment. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 3075–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, K. DNA: Differentiable network-accelerator co-search. IEEE Micro 2020, 40, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, M.L.; Xiong, X.C.; Wang, Y.H.; Qiang, B.H. DMA-YOLO: Multi-scale object detection method with attention mechanism for aerial images. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 4505–4518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wei, X.; Ji, C.; Xiang, T.; Fang, B. Optimum quality control algorithm for versatile video coding. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2022, 68, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Liu, S. HDIQA: A hyper debiasing framework for full reference image quality assessment. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2024, 70, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhou, M.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. VideoGNN: Video Representation Learning via Dynamic Graph Modelling. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Sheng, W.; Zhou, M.; Fang, B.; Luo, F.; Li, J. Method for fault diagnosis of temperature-related mems inertial sensors by combining Hilbert–Huang transform and deep learning. Sensors 2020, 20, 5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, K.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y. Bayer pattern optimization for low-light endoscopic imaging. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2021, 40, 2056–2069. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Rao, P.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H. Efficient Polarization Demosaicking Via Low-Cost Edge-Aware and Inter-Channel Correlation. IEEE Photonics J. 2025, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Zhou, M.; Liu, X. Deep tone mapping network for endoscopic image enhancement. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 3457–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Leng, H.; Fang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S. Low-light image enhancement via a frequency-based model with structure and texture decomposition. ACM Trans. Mul timed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2023, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Kim, D.; Lee, S.; Kim, Y.; Yang, J. Power consumption analysis of GPU-accelerated endoscopic image processing. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 522–533. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 60601-2-18:2023; Medical Electrical Equipment—Part 2-18: Requirements for Endoscopic Systems. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Sze, V.; Chen, Y.-H.; Yang, T.-J.; Emer, J.S. Efficient processing of deep neural networks: A tutorial and survey. Proc. IEEE 2020, 105, 2295–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Deep compression: Compressing deep neural networks with pruning, trained quantization and Huffman coding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, S.; Liu, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C. A full-reference image quality assessment method via deep meta-learning and conformer. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2023, 70, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Peng, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. Community-based social recommendation under local differential privacy protection. Inf. Sci. 2023, 639, 119002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Wei, X.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Full-reference image quality assessment: Addressing content misalignment issue by comparing order statistics of deep features. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2023, 70, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhou, M.; Jia, W. Toward Low-Latency and High-Quality Adaptive 360 Streaming. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 6326–6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Leng, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Cheng, J.; Guo, Y. Mixed-precision quantization for CNN inference on edge devices. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 43, 2970–2984. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Chen, L.; Kwong, S. Recent advances in rate control: From optimization to implementation and beyond. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Pan, H.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Q.; Lin, W. A Memory-Optimized and Energy-Efficient CNN Acceleration Architecture Based on FPGA. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 28th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–14 June 2019; pp. 2137–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, Q.; Liu, X. StreamArch: A memory-efficient streaming architecture for real-time image processing. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 30, 1347–1361. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Chen, L. FPGA acceleration of convolutional layers via loop unrolling and pipelining. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2021, 29, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Rastegari, M.; Ordóñez, V.; Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. XNOR-Net: ImageNet classification using binary convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8–16 October 2016; pp. 525–542. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, S. Complexity-based intra frame rate control by jointing inter-frame correlation for high efficiency video coding. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2017, 42, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Shang, Z.; Tan, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, R. Siamese networks with an online reweighted example for imbalanced data learning. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 132, 108947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Hu, H.M.; Zhang, Y. Region-based intra-frame rate-control scheme for high efficiency video coding. In Proceedings of the Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA), 2014 Asia-Pacific, Siem Reap, Cambodia, 9–12 December 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, W.; Zhou, M.; Fang, B.; Chen, L.; Wang, H. Spatiotemporal feature hierarchy-based blind prediction of natural video quality via transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2022, 69, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhu, L.; Han, S. ProxylessNAS: Direct neural architecture search on target task and hardware. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.00332. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, M.; Wang, X. Contrastive distortion-level learning-based no-reference image-quality assessment. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 8730–8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhou, M.; Chen, L. HotNAS: Thermal-aware neural architecture search for edge devices. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design (ISLPED), Boston, MA, USA, 1–3 August 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Xian, W.; Zhou, M.; Fang, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. A content-oriented no-reference perceptual video quality assessment method for computer graphics animation videos. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 1731–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, M. Progressive domain translation defogging network for real-world fog images. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2022, 68, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Han, S.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Transformer-Based and Structure-Aware Dual-Stream Network for Low-Light Image Enhancement. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2025, 21, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, J.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. AFES: Attention-Based Feature Excitation and Sorting for Action Recognition. In IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.; Zhou, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Q. Image Quality Assessment: Investigating Causal Perceptual Effects with Abductive Counterfactual Inference. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 17990–17999. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, X.; Xian, W.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. No-Reference Image Quality Assessment: Exploring Intrinsic Distortion Characteristics via Generative Noise Estimation with Mamba. In IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Zhou, M.; Shang, Z.; Tan, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, H. GAANet: Graph Aggregation Alignment Feature Fusion for Multispectral Object Detection. In IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dasika, G.; Sethia, A.; Robby, V.; Mudge, T.; Mahlke, S. MEDICS: Ultra-portable processing for medical image reconstruction. In Proceedings of the 2010 19th International Conference on Parallel Architectures and Compilation Techniques (PACT), Vienna, Austria, 10–15 September 2010; pp. 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Lightweight network design for endoscopic image demosaicking via accuracy-oriented NAS. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2023, 42, 2105–2116. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, H. FPGA-NAS: Bridging the gap between neural architecture search and FPGA acceleration. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2022, 71, 2056–2069. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. COFNet: Contrastive Object-aware Fusion using Box-level Masks for Multispectral Object Detection. In IEEE Transactions on Multimedia; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, H. Co-exploration of neural architectures and hardware accelerators for real-time edge intelligence. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2021, 3, 1067–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Chen, L. Fixed-hardware NAS: Limitations in adaptive FPGA acceleration. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2021, 40, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Shang, Z.; Tan, J.; Zhao, L. Beyond accuracy: Multi-objective neural architecture search for edge devices. IEEE Micro 2022, 42, 58–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, S.; Zhou, M.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, L. Image Quality Assessment: Exploring the Similarity of Deep Features via Covariance-Constrained Spectra. In IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, M.; Chen, H.; Wang, H. Accelerating hardware-aware NAS via parallelizable search for medical edge deployment. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2023, 17, 210–223. [Google Scholar]