1. Introduction

In recent years, the role of robots in industrial settings has been undergoing continuous changes. In response to the production demands of customized small-batch products, there is a growing demand for greater flexibility in production lines. Consequently, robots are required to exhibit enhanced flexibility, reduced maintenance costs, and the capability for rapid reconfiguration and deployment [

1]. Assembly tasks, as a crucial component of industrial production, significantly impact overall manufacturing productivity and quality [

2]. By combining the complementary advantages of human intelligence and adaptability with the precision, repeatability, and strength of robots, more complex and precise assembly tasks can be achieved [

3].

In HRC assembly scenarios, the role of robots has evolved from performing repetitive and fixed actions to inferring the motions of human operators, thereby enhancing the effectiveness and overall performance of the tasks [

4]. HRC systems should fully leverage the strengths of both parties. Collaborative robots possess advantages such as high strength, durability, precision, and freedom from fatigue, which can greatly enhance production efficiency [

5]. However, in certain stages of collaborative tasks, the flexibility of collaborative robots may be limited in the face of more complex scenarios and operational requirements [

6]. On the other hand, human collaborators exhibit flexibility, adaptability, creativity, and problem-solving abilities, enabling them to quickly adapt to new process sequences. However, the repetitive and fixed actions involved in these tasks can lead to fatigue and impose a significant burden on the physical well-being of workers [

7].

HRC assembly tasks encompass a class of intricate and continuous sequential tasks, wherein humans and robots coexist in the same working environment to accomplish the assembly of specific components. These assembly tasks can be decomposed into simpler individual tasks in a hierarchical manner [

8]. Moreover, the scope of these tasks extends beyond a single objective to be fulfilled within the workspace. To attain more efficient and natural multitask assembly, the robot necessitates the following capabilities: (1) the ability to comprehend multiple tasks, enabling the classification and assessment of ongoing tasks based on object affordance information within the workspace [

9]; (2) the ability to infer the operational intentions of human collaborators [

10], thereby allowing the robot to deduce the assembly sequence selection made by human collaborators using observable information in the shared workspace; and (3) the ability to plan assembly tasks, motion planning is facilitated via object affordance information and human collaborators’ operational intentions. This planning enhances both parties’ assembly efficiency and enables parallel execution of multiple assembly tasks.

Inferring the intentions of human collaborators is crucial within a shared workspace [

11]. Human behaviors introduce uncertainty to the entire system. In previous studies [

12,

13], human actions were constrained to fixed action sequences, strictly following pre-defined planning processes, and deviating from these fixed task sequences was prohibited during online execution. In [

14], the researcher predefined the assembly tasks and their execution order. However, the behaviors exhibited by human collaborators during task completion differ from those of highly automated robots. As highlighted in [

15,

16], where robots can adjust their movements based on the preferences of human collaborators. On the other hand, the robots enhance their autonomous decision-making capabilities by observing the behaviors of collaborators [

17].

To address these challenges, it is essential to plan the optimal assembly routes for different assembly scenarios. Given that non-single-task assembly significantly increases the complexity of the task space, optimization of assembly sequences must be performed based on topological, geometric, and technical constraints. The contributions of this paper are outlined as follows:

- (1)

To represent HRC assembly tasks, a task information-based assembly graph system is proposed. The serial and parallel relationships between different tasks are identified. Based on these relationships, mathematical expressions for human and robot behavioral levels are established.

- (2)

A HRC assembly dataset is established based on a simulation system, enabling the generation of high-quality assembly sequences. Concurrently, an evaluation method based on explicit trajectories and implicit assembly information is developed. This method is used to simulate human assembly preferences and quantitatively assess the quality of assembly sequences.

- (3)

A two-stage MLP-LSTM network is employed to realize sequence generation and evaluation for new assembly scenarios, thereby achieving optimal assembly sequence prediction and HRC task planning under different initial assembly environments.

2. Related Work

In traditional manufacturing, assembly is a time-consuming and energy-intensive process [

18]. In conventional industrial robot production scenarios, robots are often confined within fences and tasked with repetitive and fixed operations [

19]. In unstructured environments, robots require reprogramming, resulting in significant reductions in production efficiency [

20]. With advancements in robot intelligence, it has become possible for robots and humans to collaborate in shared workspaces to accomplish common tasks [

5]. Currently, there have been numerous studies on strategies for HRC assembly tasks [

21,

22]. The key elements in such research include complex task information representation, recognition of human intentions during the assembly process.

2.1. HRC Task Representation

Numerous studies have proposed modeling approaches for expressing HRC task representations. Homem de Mello and Sanderson [

23] were the first to represent assembly plans using AND/OR graphs, which represent assembly tasks as directed acyclic graphs. This approach enables hierarchical representation of complex assembly tasks and provides the ability to search for feasible assembly sequences. Similar research [

24] decomposed assembly tasks into individual subtasks using a hierarchical structure and represented the tasks based on the dependencies between the subtasks. In [

25], assembly tasks were modeled as a three-layer framework using AND/OR graphs, and a cost function was computed offline to select assembly strategies. However, the uncertainties in online robot perception and motion were not addressed, and the robot merely performed passive assembly actions. In recent research, AND/OR graphs have also been applied in multi-agent environments for HRC [

26,

27]. Optimal assembly sequences can be searched offline [

28] and online [

27], but AND/OR graphs face challenges in modeling tasks in the temporal dimension for parallel assembly tasks. In [

29], Casalino et al. modeled the unpredictability of human behavior in HRC using a Partially Controlled Time Petri Net (TPN). Additionally, behavior trees have been frequently mentioned as a method for task representation in HRC tasks, and they have been used in industrial environments to create and monitor task plans for industrial robots [

30]. However, robots struggle to adapt to flexible and changing human behavior. For human–robot assembly tasks, ref. [

31] proposed a generic task allocation method based on Hierarchical Finite State Machines (HFSMs). The developed framework first decomposes the main task into subtasks modeled as state machines. Based on considerations of capabilities, workload, and performance estimation, the task allocator assigns the subtasks to human or robotic agents. In recent years, Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated breakthrough performance in the field of contextual semantic understanding [

32]. Particularly, in HRC scenarios, their core value as high-level semantic task planners has been fully verified [

33].

However, as complex assembly tasks are characterized by uncertainty, complexity, and diversity, expressing them via graphical means allows for the assimilation of highly unstructured information into computable models. This provides a framework for obtaining optimized task sequences and constitutes the most fundamental step in realizing HRC assembly tasks.

2.2. Human Intention Recognition for HRC

The HRC process aims to achieve efficient assembly tasks. This requires the robot to infer the behavior of human collaborators within the shared workspace. A key focus in this inference process is recognizing human intentions. Prior research on human intention recognition models can be categorized into two main approaches: explicit representation and implicit representation of task-related human intentions.

Explicit human action behavior representation primarily involves sensing human motion information through sensors. In [

30], a robot employed a methodology to capture different human motion patterns and unmodeled dynamics for more accurate human action perception. Andrianakos et al. implemented automatic monitoring of human assembly operations using visual sensors and machine learning techniques [

31]. Natural interaction in HRC can be achieved through gesture recognition and human re-identification, enabling the robot to accurately perceive human attention and infer their intentions [

34,

35]. Wearable motion sensors provide another approach. In [

36], Gaussian Mixture Models and Gaussian Mixture Regression were used to model action templates from inertial datasets obtained from sensors worn by operators, and online pattern matching algorithms were applied to detect and recognize meaningful actions performed by the operator. Unlike directly acquiring human motion information, implicit representation methods primarily express human intentions through the collection of task information and control of the assembly process. In [

37], human intentions were modeled as a continuous sequence of assembly states that the operator considers from the current time onwards, which is translated graphically as various paths in an assembly state graph. Ravichandar et al. [

38] proposed a novel approach to infer human intentions by representing them as the motion goals to be reached, using a neural network-based approximate Expectation Maximization algorithm and online model learning. Lin et al. [

39] treated human intentions as hidden variables and predicted human assembly efficiency using Hidden Semi-Markov Models (HSMM). With the development of deep learning, the HRiRT model proposed by [

40] achieves human intention recognition (hand force estimation) by integrating the Transformer architecture. Similarly, ref. [

41] adopts the encoder module of Transformer, leveraging its self-attention mechanism to capture long-sequence dependencies in motion trajectories, which is applied to the key link of human intention recognition. In addition, ref. [

42] infers human intention targets by aggregating neighborhood information through Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and generates semantic robot action plans. The method in [

43] uses a shared GNN encoder to enable the model to simultaneously learn the latent space representations of three tasks—action recognition, action prediction, and motion prediction—thus realizing an end-to-end multi-task inference framework.

Explicit human intention recognition methods are commonly used in multitask assembly scenarios. However, these methods exhibit limitations in real-time performance and efficiency. Human intentions typically revolve around specific goals. Hence, integrating task information with the current environmental data becomes a critical factor in effectively discerning human intentions.

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Statement

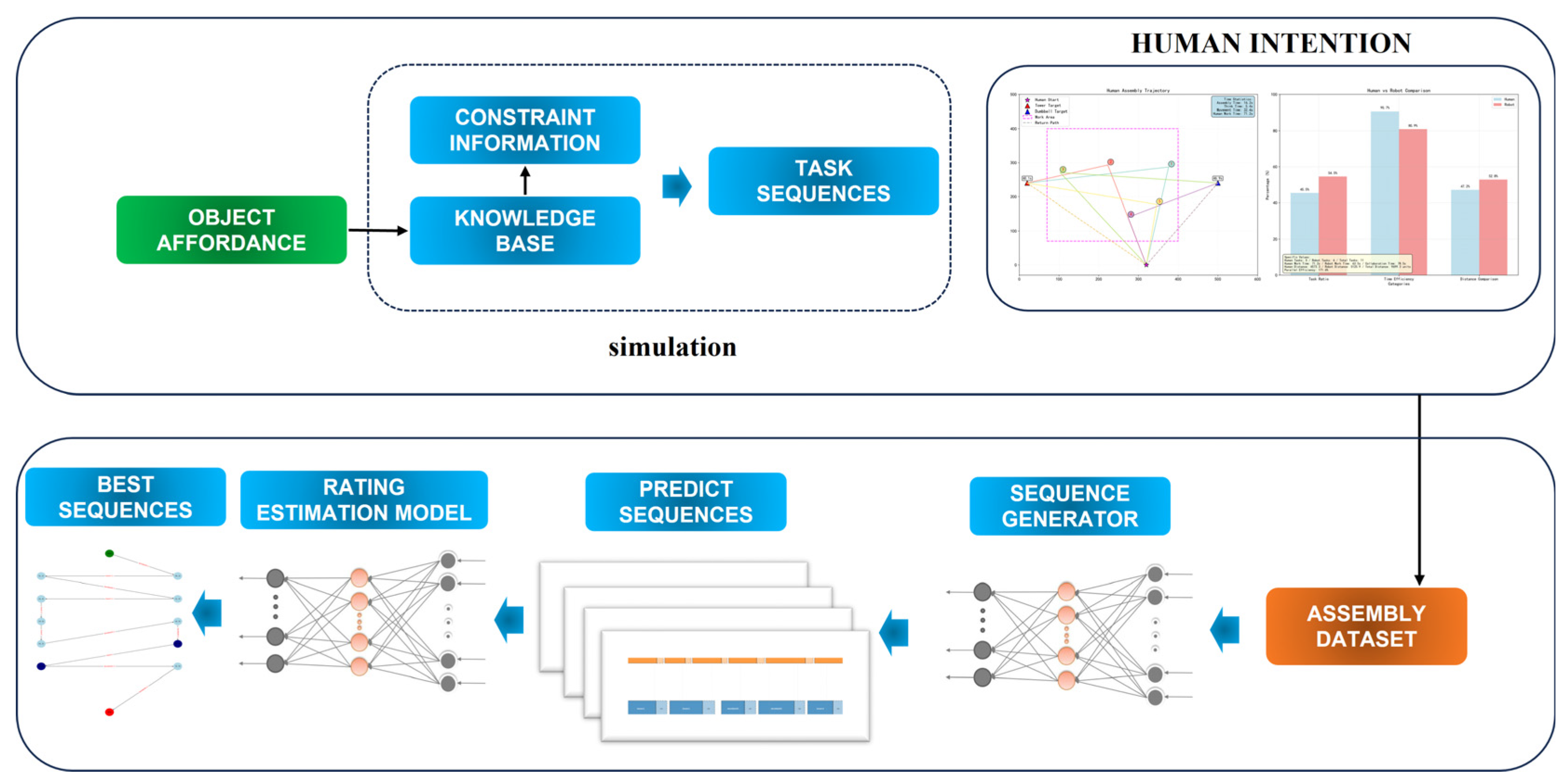

This study aims to generate real-time HRC task graphs for assembly scenarios, with the specific workflow illustrated in

Figure 1. First, mathematical expression of task information is completed based on domain knowledge to generate an offline assembly feasible path graph. However, due to the diversity of feasible task sequences, it is necessary to select the optimal assembly sequence, for which a two-stage MLP network is employed in this paper. Nevertheless, the involvement of human collaborators introduces uncertainty into the HRC system, thus requiring further optimization of the assembly sequence based on human intentions.

3.2. Offline Task Graph for Human–Robot Collaborative Assembly

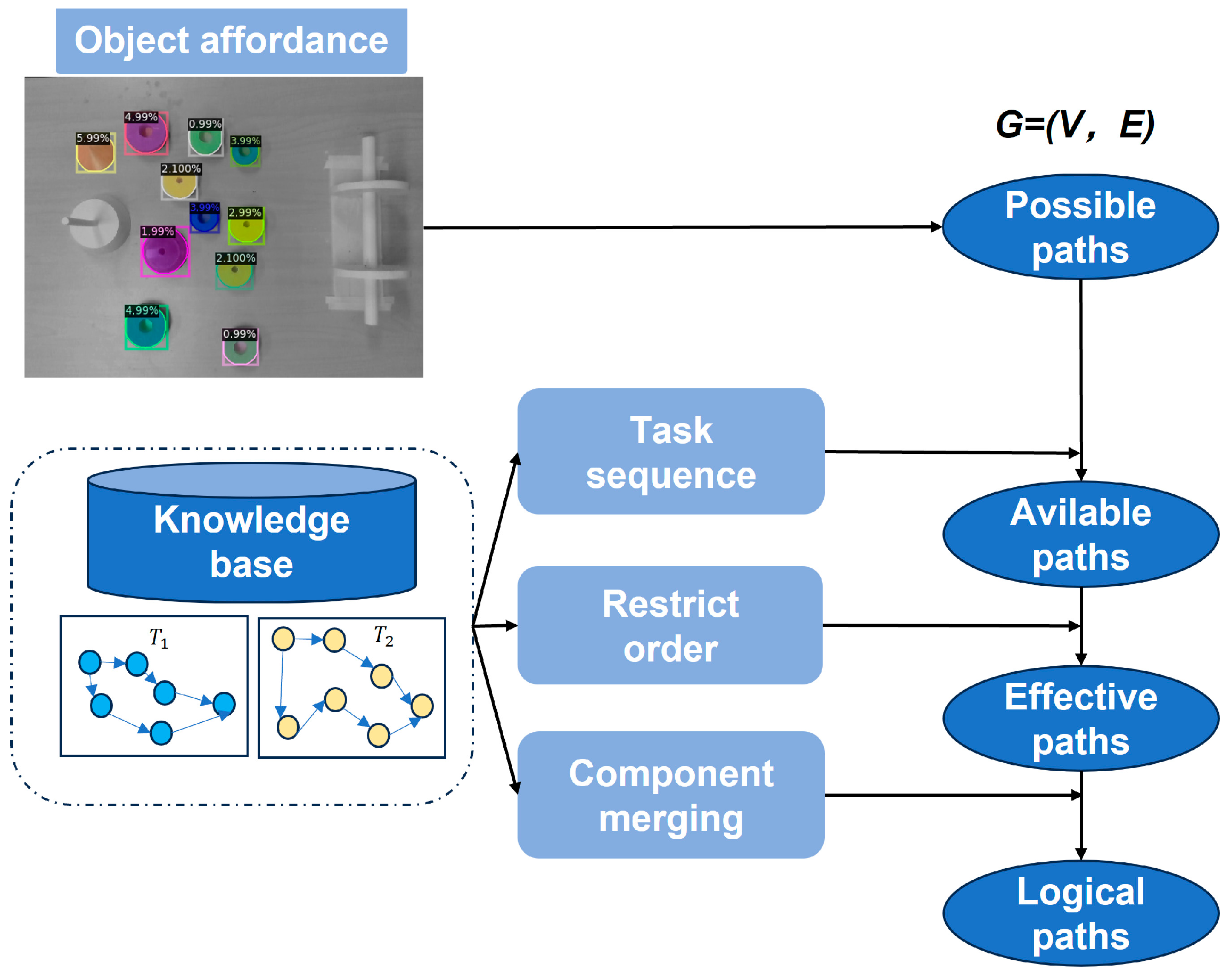

The proposed task representation framework in this paper, as depicted in

Figure 2, enables the robot to comprehend task information through a task graph, thereby avoiding the repetition or erroneous execution of tasks that could lead to a decrease in assembly efficiency. Particularly in the case of multi-task assembly operations, where the assembly sequence is not unique, human operators possess an advantage in understanding the assembly of multiple tasks.

The proposed behavior graph in this paper is a type of directed acyclic graph based on object affordance information and task information. The object affordance set is expressed as

represent the affordance of

in task a. The set of object affordance information comprises the names of components, the quantity of components, and the respective physical locations of each component. These factors serve as criteria to determine the feasible task types at the current stage. The task information is represented as a collection of assembly part sequences, denoted as

represents the assembly sequence of an individual task, where each

enotes the specific component involved in the assembly process. In behavior graph, each vertex V represents a collection of different components, while the edges E between vertices represent the progress of assembly tasks. We employ Algorithm 1 to construct the offline part of the behavior graph.

| Algorithm 1: Offline Behavior Graph Construction Method |

|

|

|

|

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

13:

14:

15:

16:

17:

18:

19: |

In comparison to the behavior graph of a single task, the behavior graph of multiple tasks exhibits a significant difference in the number of feasible paths. However, within the set of feasible paths, there exist samples that do not conform to the assembly rules, thereby affecting the overall effectiveness of the assembly graph. Algorithm 2 is proposed, which aims to eliminate potential assembly paths that do not comply with the specified assembly rules. Based on the specified assembly order for each assembly component within the subtasks, respective logical distance values

are defined, resulting in the assembly value set

, for the entire assembly sequence. The logical distance

is defined as the sum of logical distances of individual subtasks within a given path. Paths that strictly adhere to the feasible assembly rules will have a logical distance of 0, and are thus selected as

. The path selection logic in Algorithm 2 is designed to filter out the greatest common divisor (GCD) of paths. By comparing logical distances, it reduces the number of path heuristics and simplifies the complexity of subsequent assembly path sequence generation.

| Algorithm 2: Path Screening Method Based on Logical Distance |

|

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

12:

13

14:

15:

16:

17:

18:

19: |

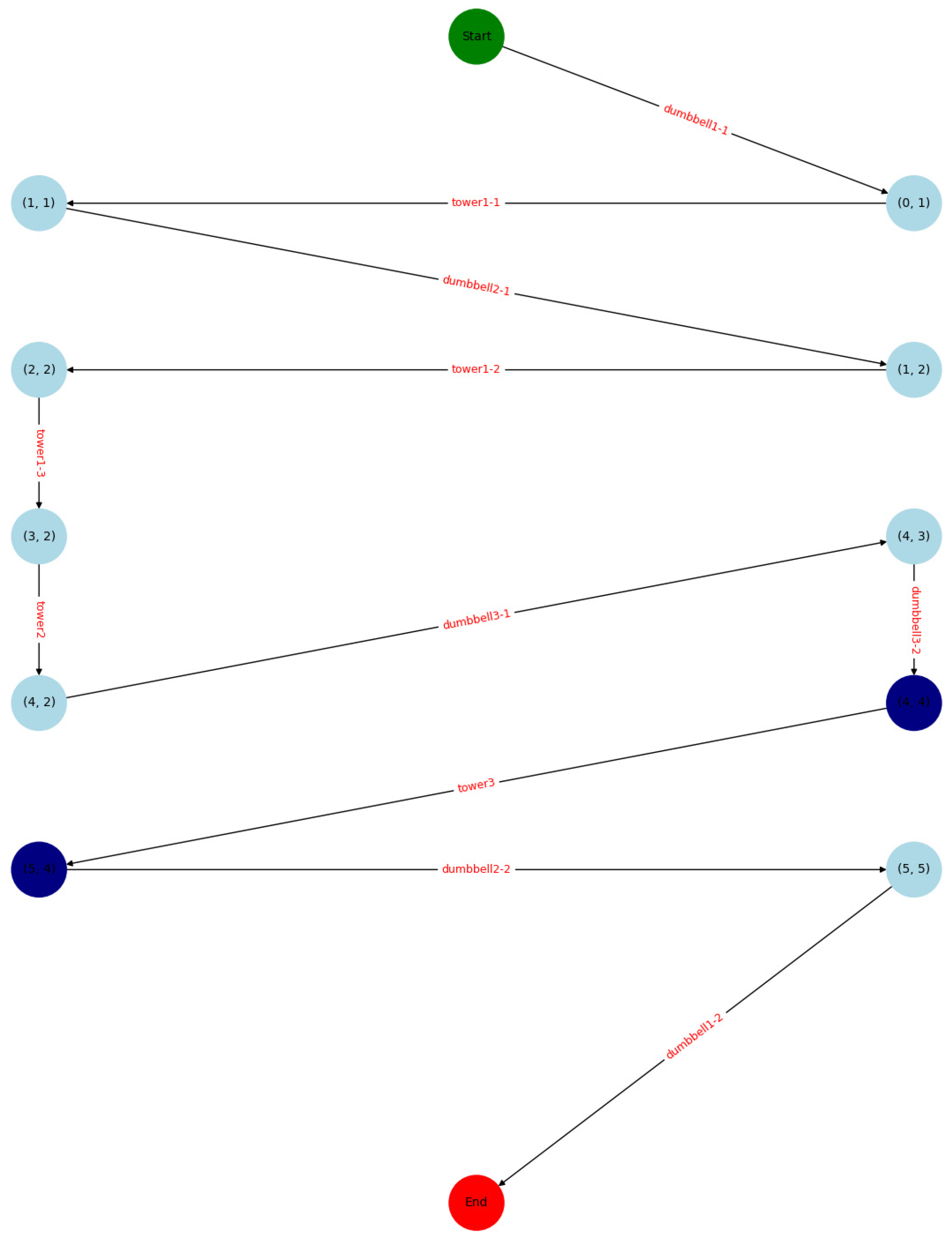

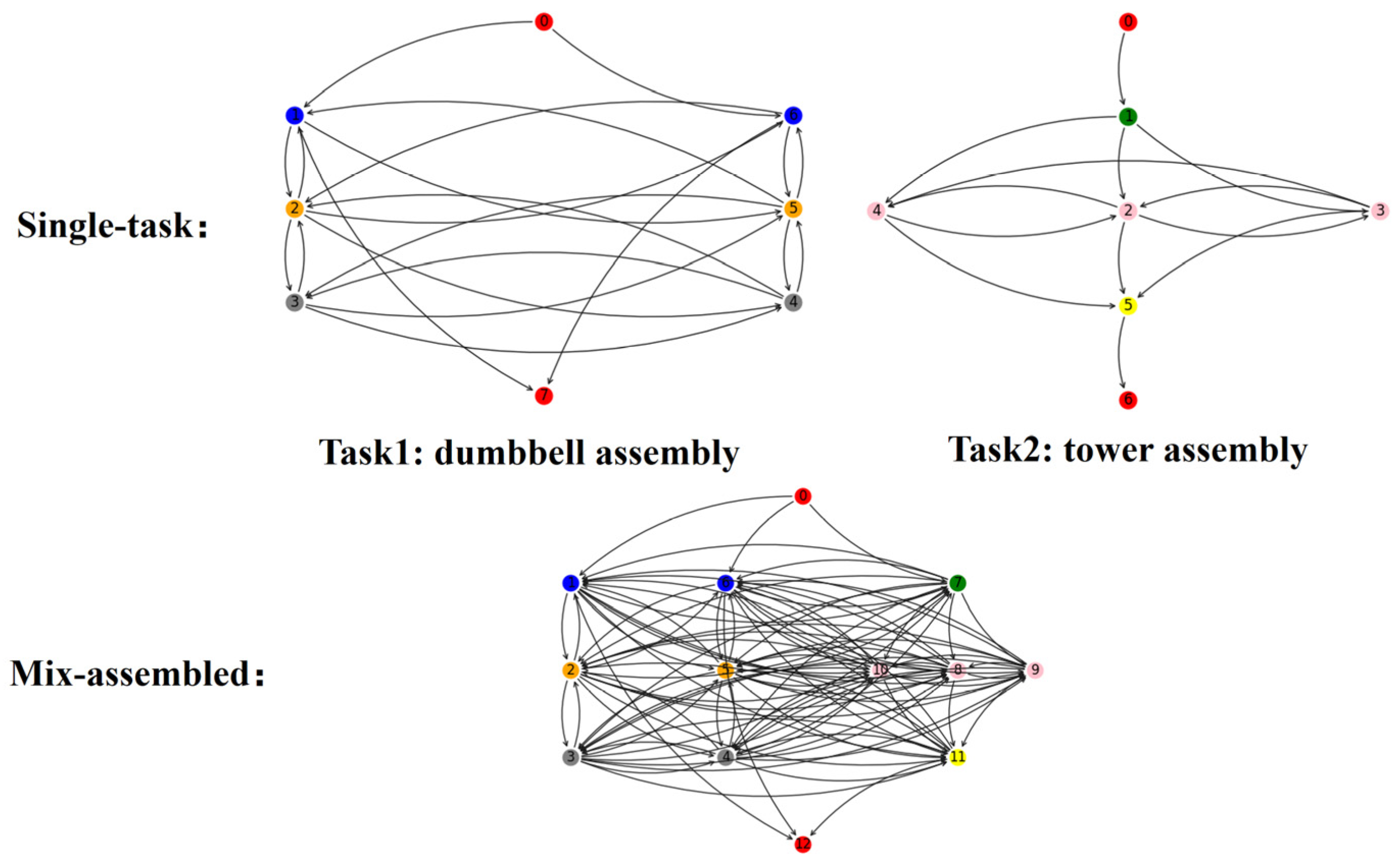

An assembly state graph for the task can be generated. Unlike behavior graphs where each node represents a part to be assembled. The assembly state graph depicts changes in task states during the assembly process. Each node is a vector with a dimension equal to the number of tasks, reflecting basic assembly logic and serving as a mapping of the part space to the task space. As illustrated in

Figure 3, nodes in dark blue represent tasks that must be performed by humans.

3.3. Two-Stage MLP-LSTM Training Network

The HRC assembly task graph contains task sequences for assembly. However, variations in the initial positions of parts lead to differences in initial assembly states, rendering many feasible sequences non-optimal. To obtain the optimal assembly sequence, this paper proposes a two-stage MLP training network.

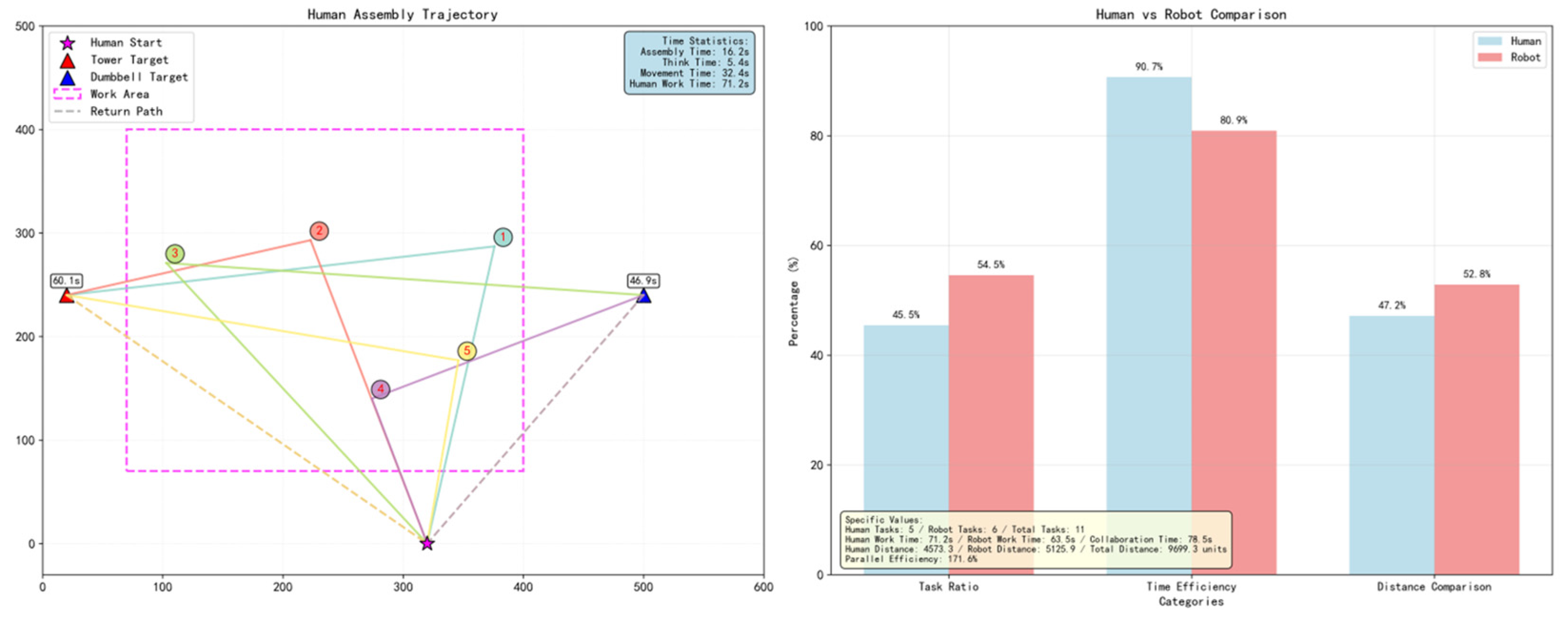

The quality of assembly sequences is influenced by the coupling of multiple factors (time, load, collaboration, and spatial pose), making it difficult to fully characterize using analytical rules. A labeled dataset is constructed to enable the model to learn nonlinear scoring mappings through supervised learning, thereby enhancing its generalization ability to unseen scenarios. Since collecting motion information in actual HRC scenarios consumes substantial resources, this paper uses simulation data to build a dataset for HRC assembly graphs. As shown in

Figure 4, human assembly intent consists of two parts: explicit expression via human operation trajectories

, which reflects humans’ part selection preferences during assembly, and implicit expression via Human–Robot assembly information (e.g., task allocation ratio, assembly time ratio, assembly distance ratio). Among this information, blue represents the assembly information of human collaborators, while pink represents that of the robot. This information reflects humans’ preferences for the overall performance of the assembly process. Expert scoring of high-quality assembly sequences is performed based on the above two parts.

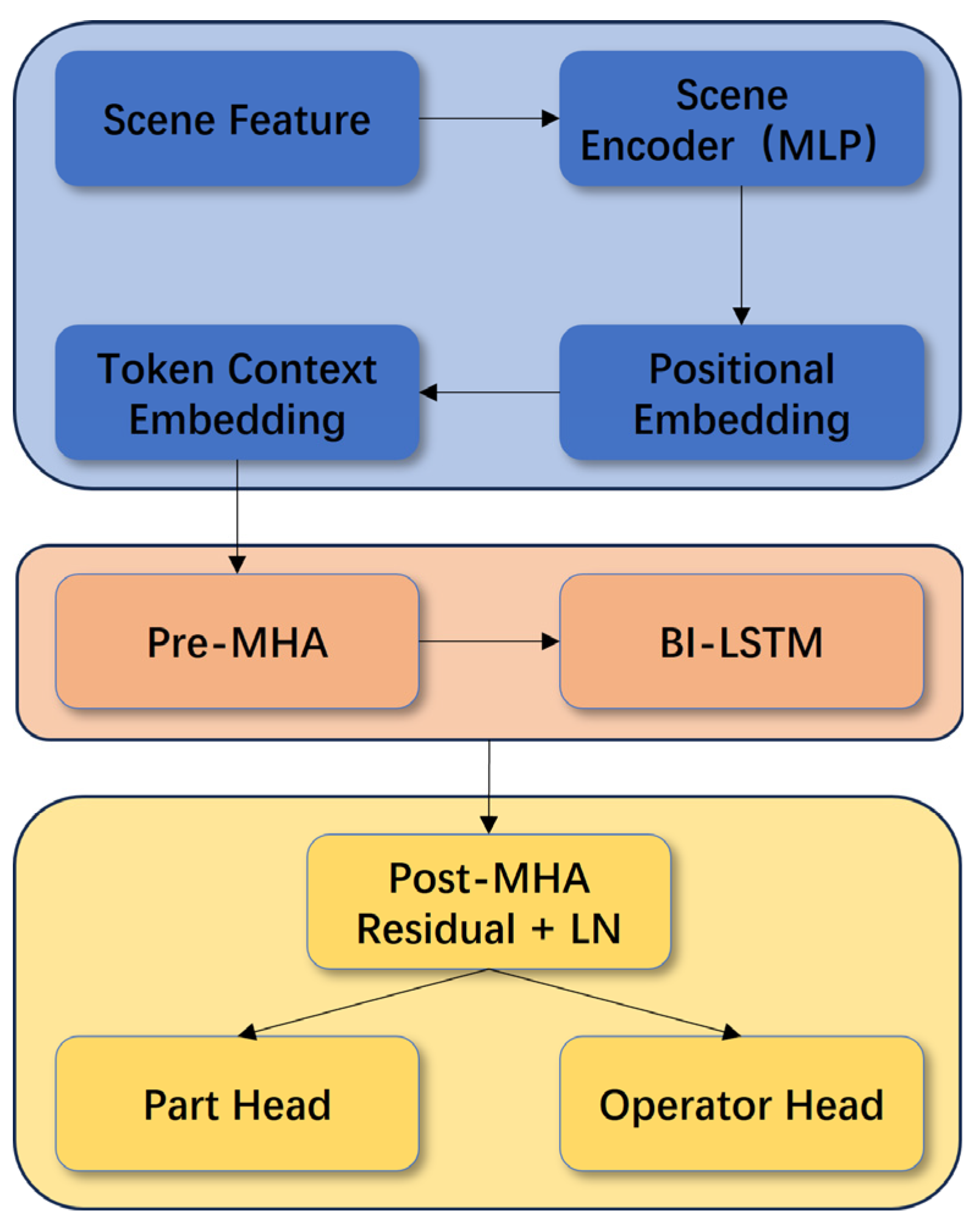

Based on high-quality assembly sequences in the database, this paper employs a temporal network to learn scene geometry and prior constraints, generating executable and relatively efficient assembly sequences for different assembly scenarios. The specific implementation workflow of the sequence generation network is illustrated in

Figure 5. The generator consists of three main components: Scene Encoder, Pre-Multi-Head Attention (Pre-MHA) & Temporal Modeling (Bi-LSTM), and Post-Multi-Head Attention with Normalization (Post MHA + Residual + LN). Two parallel prediction heads are connected to output component and executor categories.

Scene features consist of two categories: fine-grained position features and spatial relationship features. The former counts the number of instances for each component category, and records normalized coordinates and presence indicators for up to K instances according to a fixed upper limit K, thereby establishing a comparable fixed-length representation. The latter encodes the geometric layout across components by calculating cross-category neighbor pairwise distances, relative displacements, and category indices. These two types of features are concatenated as model inputs, enabling the network to perceive both multi-instance distributions and cross-category geometric correlations. The scene feature is projected into a global embedding via MLP; is expanded to sequence length and combined with learnable positional encoding to form ; further, it is added to tokens composed of previous-time-step token (component/executor) embeddings to obtain X. Temporal representation Y is derived through multi-head self-attention and multi-layer bidirectional LSTM, followed by lightweight self-attention, residual connection, and layer normalization to yield U. Finally, the parallel linear heads—Part Head and Operator Head—project U to the component vocabulary dimension and operator vocabulary dimension , respectively, generating and . During inference, autoregression is adopted: at each step, sampling is performed based on and , and an “assembly order and quantity constraint” mask is applied to only allow feasible component candidates at the current step. Probabilistic selection is then conducted on these candidates to ensure the sequence complies with process order. For “human-exclusive” steps, is forced to select humans, guaranteeing task allocation adheres to rules.

Based on the assembly sequences generated by the aforementioned sequence generation network, we propose an LSTM-based sequence scoring network to evaluate the execution quality of assembly sequences. This network adopts a dual-branch architecture: a positional encoding branch and a sequence modeling branch, which ultimately fuse features via a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) and output a scalar score.

The input to the network is a joint state set of part positions and assembly sequences, where the position vector , (, N denoting the number of part categories and k representing the coordinate dimension) and the sequence index matrix , with each row containing two indices:

: Part index

: Executor index, where

The part embedding function maps discrete part indices to continuous high-dimensional vector representations:, where denotes the part embedding vector at time t. The executor embedding function maps executor types to embedding vectors: , representing the executor embedding vector at time t. For each time step t in the sequence, we concatenate the part embedding and executor embedding to form a fused representation: . The fused sequence features are fed into an LSTM network for temporal modeling: , where the LSTM can be a bidirectional structure with an output dimension of . H denotes the hidden state sequence of the entire sequence. The final hidden state of the LSTM is used as the global representation of the entire assembly sequence:. Feature refinement is performed on the sequence representation using layer normalization and linear transformation: . Nonlinear transformations via several fully connected layers yield the predicted score , with mean squared error (MSE) adopted as the regression loss. The scoring network is trained on the scored sequences from the database to obtain high-score generated sequences.

4. Case Study

The method proposed in this paper is validated in HRC assembly scenarios. To verify the effectiveness of the method under reasonable environmental constraints, the following assumptions are made for generalized assembly scenarios.

Assumption 1: Unlike [

40], where types and positions of all assembly components are predefined, this paper simulates a most generalized assembly environment. Thus, the positions of task parts are not identical, and the robot needs to perceive environmental information and object affordances before performing tasks.

Assumption 2: To verify the effectiveness of the method in a multi-task environment, the number of operators and robots in the assembly environment constructed in this paper is strictly limited. This paper discusses how to complete multi-task assembly in a one-to-one robot-operator assembly system.

Assumption 3: Each individual assembly task discussed in this paper has a specific assembly sequence, which must follow certain constraint orders to ensure the smooth completion of the task. Corresponding assembly sequences have been predefined in the knowledge base; however, there is no explicit assembly order between parallel tasks.

Assumption 4: Due to the limitations of the robot’s end effector, certain assembly steps can only be completed by human collaborators. This paper incorporates this factor as an action constraint in HRC to plan robot actions.

Assumption 5: This paper aims to improve the efficiency of HRC in a multi-task environment while ensuring safety in collaboration. It is assumed that when there is an overlap between human motion trajectories and robot action trajectories, the robot will adopt a strategy to avoid the movement path of human collaborators.

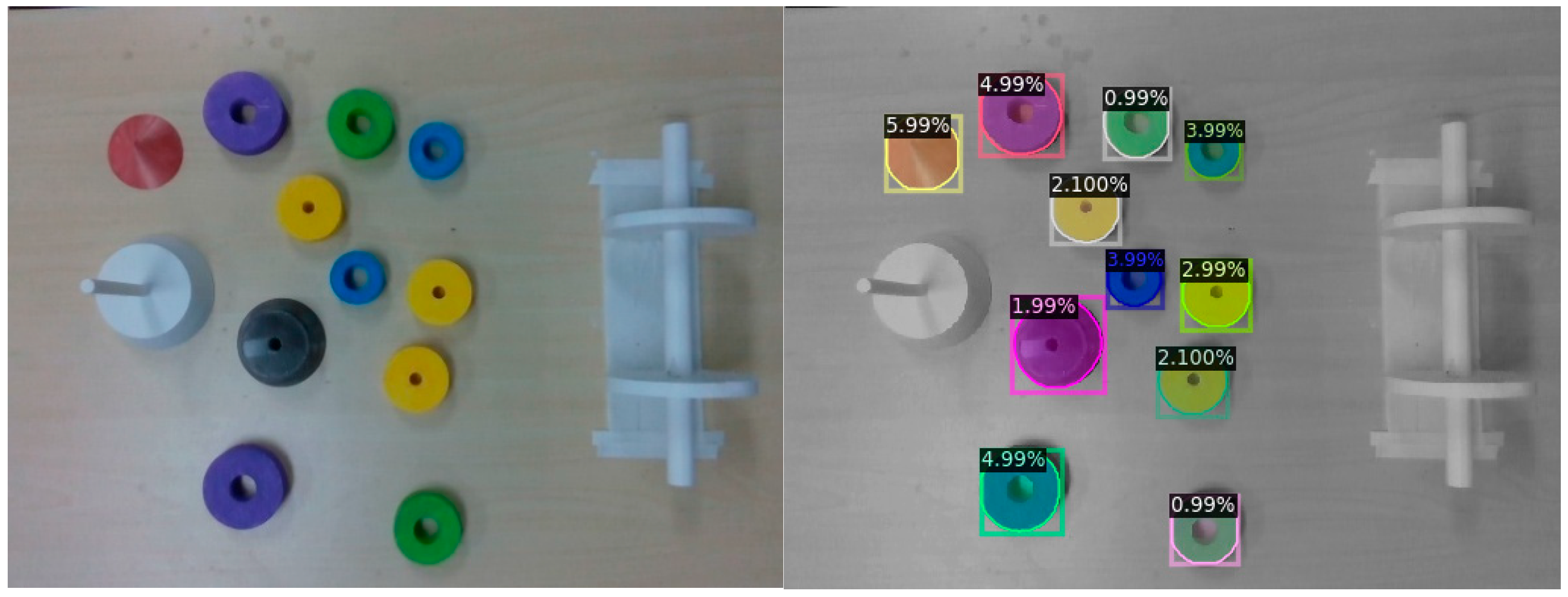

The assembly tasks studied in this paper are illustrated in

Figure 6, mainly including the assembly of two types of objects: dumbbell assembly and tower assembly. Each component of the assembly can be assigned to either a robot or a human collaborator. The assembly difficulty of the two tasks is set to be similar, aiming to reduce the variability of different operators across different tasks.

The dumbbell-shaped assembly task involves 3 types of objects and 6 components, with the components featuring the following characteristics:

- (1)

Fully sequential assembly: There is a size relationship between components, which must be assembled in descending order of size.

- (2)

Three pairs of identical components: During assembly, the selectable components may not be unique.

- (3)

Symmetric assembly: Mirror image action sequences exist.

- (4)

Human-exclusive assembly for one component: Due to assembly orientation constraints, one component must be assembled by a human.

The other assembly task is to complete the assembly of a tower-shaped object. This type of object assembly is designed to involve 3 types of objects and 5 components, with the components having the following characteristics:

- (1)

Incomplete sequential assembly: The positions of components can be swapped.

- (2)

One type of identical components: There exists a category of identical components.

- (3)

Asymmetric assembly: It can only be assembled in a specific order.

- (4)

Human-collaborator-exclusive final assembly: The assembly of the last component must be completed by a human collaborator.

5. Experiments

In multi-task assembly scenarios, during the assembly of subtasks, there exist states where tasks interact with each other, while both parties must strictly follow the assembly sequence of subtasks. This process is referred to as relative sequential assembly, which endows the assembly process with multiple select ability. As shown in

Figure 7, mixed assembly involves a large number of feasible paths.

The real robot platform includes a RealSense D435i depth camera and a UR5 collaborative robot. However, since implementing the robot’s shaft-hole assembly operation is not the main research content of this paper, the experiment uses the PyBullet simulation environment for sequence simulation.

In this paper, 400 high-quality assembly sequences under different assembly scenarios are generated through dynamic constraint algorithm simulation. Combining domain knowledge, after balancing assembly information such as human assembly trajectories and HRC resource allocation, 20 distinct and relatively optimal assembly paths are generated for each scenario. Then, two skilled operators and two unskilled operators score each path, considering both explicit human movement trajectories and implicit collaborative information (e.g., assembly time and the proportion of human idle time) from multiple dimensions.

Since labeling costs increase exponentially with the number of scenarios, the study adopts a part position drift method for data augmentation—by applying slight drifts to the position of each part and its corresponding score. Ultimately, 12,000 optimized assembly paths and their respective scores are formed.

In the sequence generation stage, we adopt a type of LSTM generation model conditioned on scene features. The model first encodes scene embeddings using a two-layer feedforward network (with ReLU as the activation function and the hidden layer dimension set to 128). Subsequently, the scene representation is concatenated with autoregressive word embeddings and input into a two-layer LSTM for sequence modeling (with 128 hidden units, 2 layers, and a dropout rate of 0.2). The training configuration includes a learning rate of

, the AdamW optimizer (equipped with ROP scheduling), a batch size of 16, and a maximum of 100 epochs. A linear mapping is used to obtain the conditional distribution over the vocabulary, which is employed to incrementally sample assembly sequences. In the sequence scoring stage, we use an LSTM regressor that jointly models assembly sequence embeddings and position features to score the quality of candidate sequences. The model consists of a one-layer LSTM (1 layer with 128 hidden units), whose input is formed by concatenating discrete embeddings of parts and executors (with dimensions 64 and 8, respectively). The LSTM output, after LayerNorm and linear transformation, is jointly input with the scene position vector into a two-layer feedforward network (with hidden layer dimensions of 256 and 128, ReLU as the activation function, and a dropout rate of 0.1) to generate a scalar score. For training configuration, the Adam optimizer is used (with a learning rate of 1 × 10

−3 and weight decay of 1 × 10

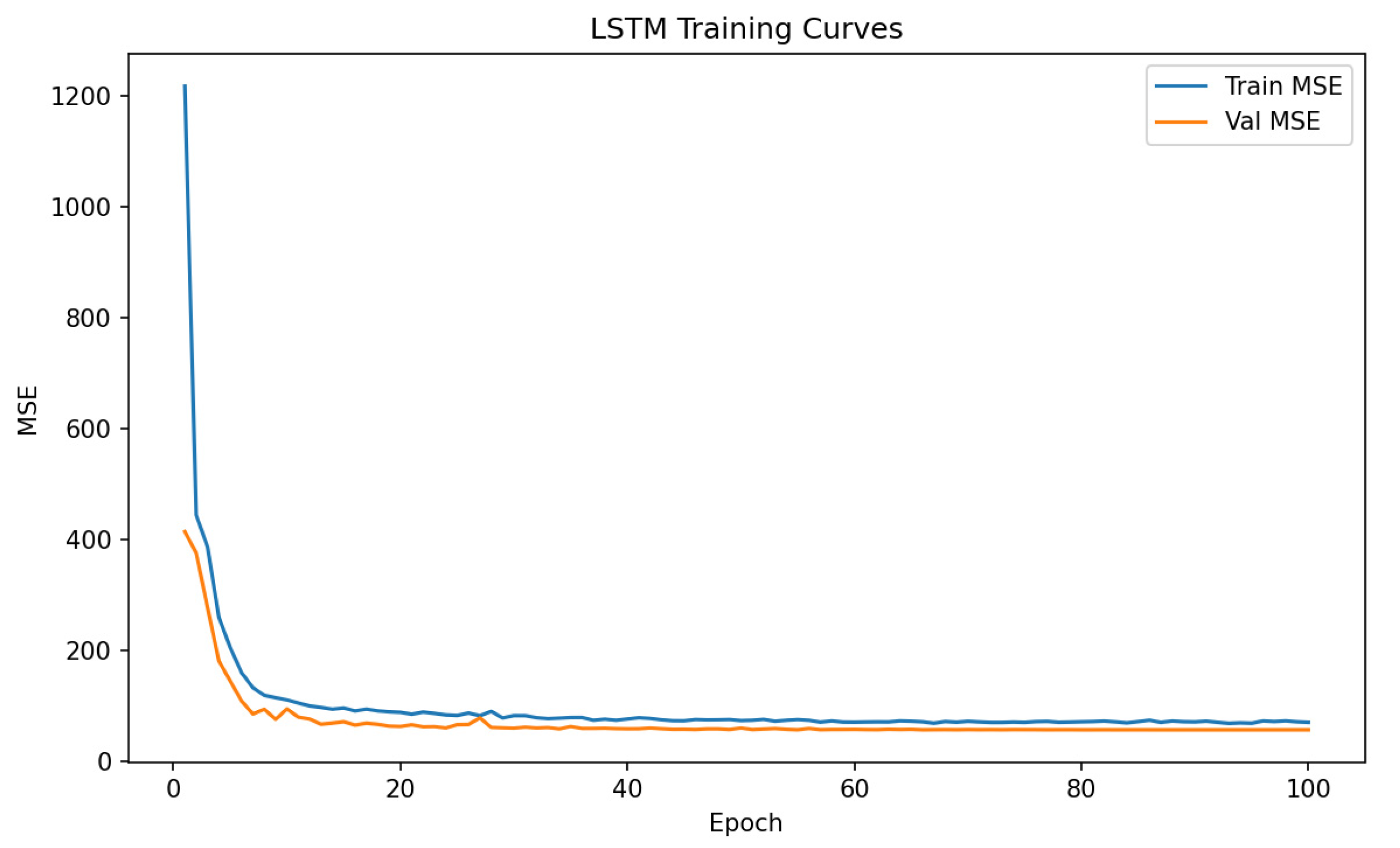

−4), along with a batch size of 128 and 100 training epochs. This experiment is equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU and adopts the Python + PyTorch 2.5.1 deep learning framework. The loss results of the scoring model training are shown in

Figure 8. Blue represents the MSE of the training set, and orange represents the MSE of the validation set. The model loss had converged when trained to 40 epochs. Since the number of parts used in our experiment is not large, the training cost of our sequence generation network is relatively low. For an 11-stepHRC sequence, the generative model takes 13.5 s per epoch, with a total training time of 8.1 min; the scoring model takes 1.32 s per epoch, with a total training time of 2.2 min. The average time for a single sequence inference is 378.8 ms, and the time to score one sequence is 0.95 ms. This means 2.6 sequences can be generated and evaluated per second.

We validated the proposed method using 100 regenerated scenarios and compared it with several state-of-the-art models, including Greedy Search [

38], Depth-First Search (DFS) [

39], and Breadth-First Search (BFS) [

40].

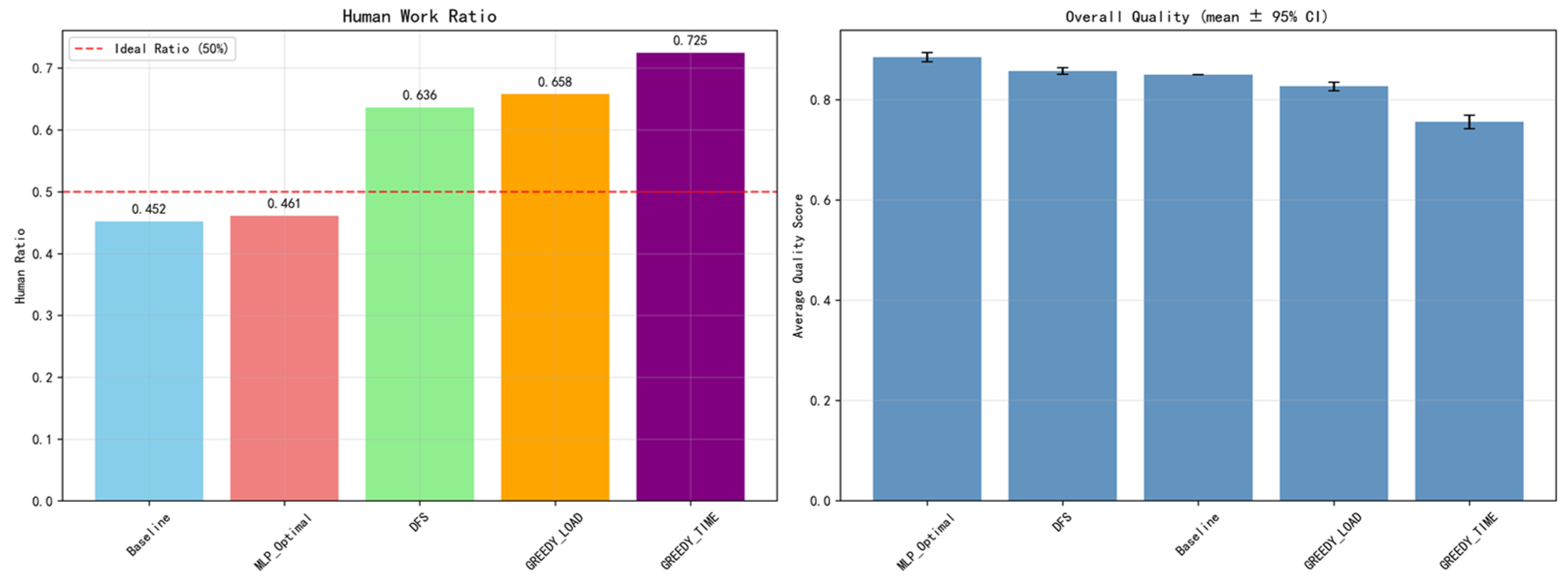

First, we conducted simulation comparisons based on the optimal sequences generated by each method. As shown in

Figure 9, in terms of the comprehensive quality dimension—composed of three types of sequence structural features with weighted values: balance (40%, requiring the Human–Robot work ratio to be close to 0.5), collaboration efficiency (30%, requiring the role switching frequency to be within a reasonable range), and task continuity (30%, requiring the maximum continuous task duration for the same executor to not be excessively long)—MLP_Optimal significantly outperforms other methods. Specifically, the average comprehensive quality of MLP_Optimal is 0.8846, which is higher than that of DFS (0.8572), Baseline (0.8500), GREEDY_LOAD (0.8268), and GREEDY_TIME (0.7558). This indicates that MLP_Optimal has greater advantages in the overall optimization of balanced task allocation, reasonable switching rhythm, and continuity constraints.

In addition, from the perspective of Human–Robot division balance (with an ideal ratio of 0.5), the average human work ratio of MLP_Optimal is 0.4610. Its deviation from the ideal ratio (0.0390) is smaller than that of Baseline (0.0482) and significantly lower than that of DFS (0.1364) and the two Greedy strategies (0.1580/0.2246). The above results demonstrate that while improving the overall quality of sequences, MLP_Optimal better maintains the balance of Human–Robot workload, and thus has higher usability and potential robustness. Meanwhile, in Scenario 51, the human ratio of MLP_Optimal is 0.61, which deviates significantly from the ideal ratio of 0.5. Additionally, the maximum number of consecutive human tasks is 6, resulting in humans performing tasks for extended periods. Such failure cases mainly stem from the unbalanced spatial layout of the scenario and the model’s insensitivity to local constraints.

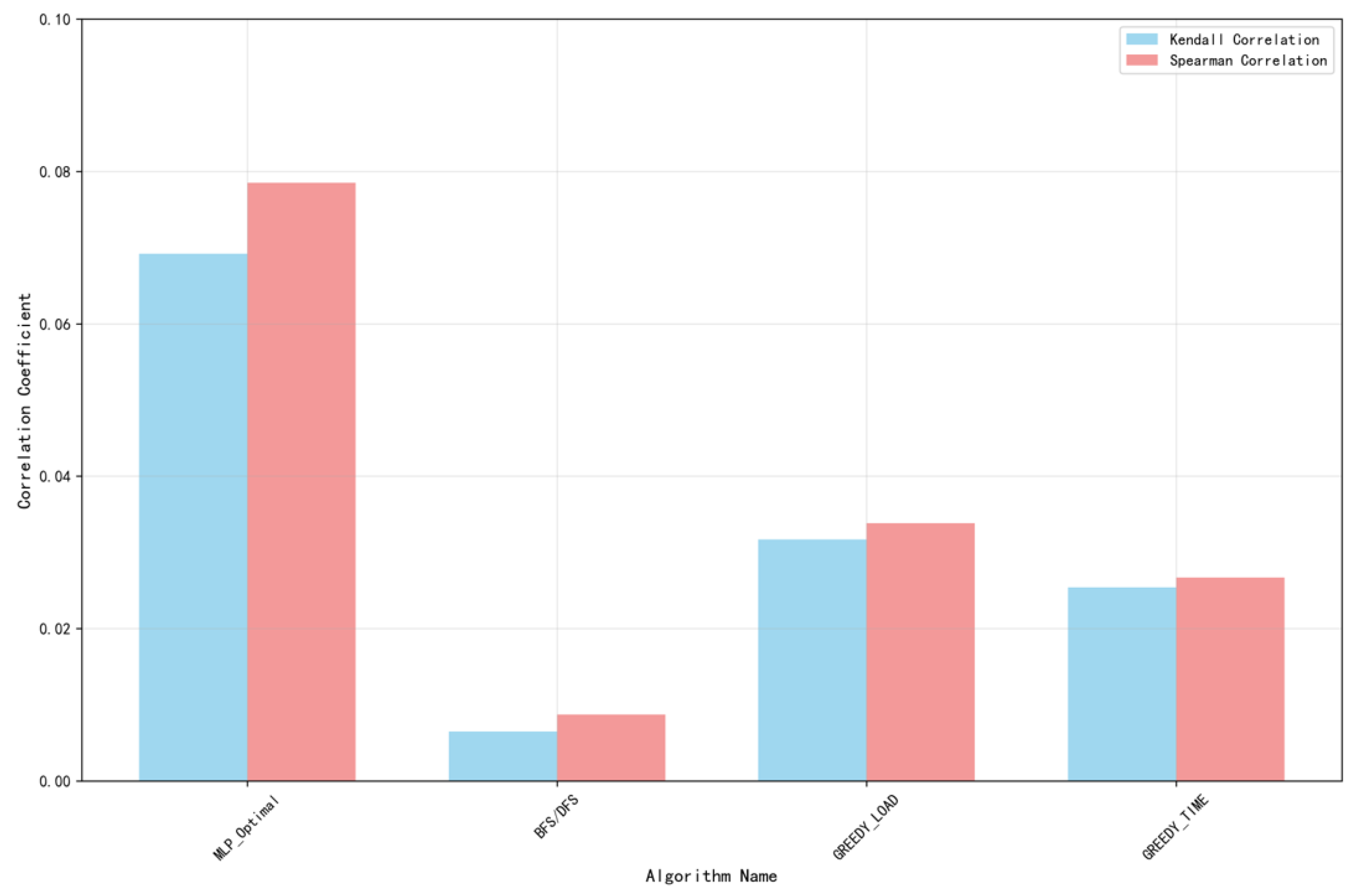

Since we need to compare the differences between different sequences, this paper also adopts the Kendall rank correlation coefficient [

41] and Spearman rank correlation coefficient [

42] to evaluate the performance of each method. By comparing with the optimal sequences evaluated by human experts, as shown in

Figure 10, the proposed two-stage generation method achieves the best performance in both the Kendall coefficient and Spearman coefficient metrics. Due to the addition of speed noise in the simulation process, the assembly time of each assembly step is roughly similar, resulting in an overall low correlation coefficient. However, compared with other algorithms, the method in this paper can still clearly learn the pattern of humans selecting optimal assembly paths.

6. Conclusions

HRC assembly plays a crucial role in the field of intelligent manufacturing. However, different initial assembly scenarios give rise to a variety of complex feasible assembly paths. Generating optimized assembly sequences is a key step in improving assembly quality and the assembly experience of human collaborators. To reasonably arrange the work of humans and robots in a shared space, task planning needs to be carried out based on human preferences and intentions. This study established an assembly simulation database, and through a two-stage MLP-LSTM sequence generation and scoring network, learned human preferences in HRC assembly tasks. Optimized assembly sequences were generated according to different initial assembly scenarios, balancing Human–Robot resource allocation and overall task efficiency. This study has clear engineering application value. The proposed sequence encoding and MLP methods are sensitive to key constraints such as task allocation ratio, collaborative switching, and continuity, enabling rapid migration to larger-scale assembly lines without modifying production hardware. We suggest integrating weak supervision and self-supervision strategies: using simulation-generated feasible sequences and process rules to automatically generate pseudo-labels, combining active learning to select a small number of high-value scenarios for manual annotation, and reusing existing model capabilities through transfer learning/incremental learning. This approach can control the demand for manual annotation within a manageable range.

Nevertheless, this study also has several limitations: (1) The method relies on a high-quality assembly simulation database, and the cost of data collection for real HRC tasks is very high. (2) No assembly sequence that dynamically tracks task status in real time has been established. (3) The evaluation of sequence quality relies excessively on manual work, and the optimal sequence obtained through final evaluation may not necessarily be the globally optimal one. (4) The ability to generalize to new assembly tasks is insufficient, requiring prior knowledge of task information and assembly constraints. (5) Restricted by sensor performance, visual sensors are prone to part pose recognition deviations under complex lighting conditions (e.g., direct glare, backlighting) or occluded scenarios. (6) The operational flexibility of robot end-effectors is limited, which cannot fully match the fine movements of human hands; moreover, the safety distance setting in the HRC space limits operational efficiency, making it difficult to balance safety and assembly speed. Future research can be conducted in the following aspects:

First, a “hybrid dataset augmentation framework” integrating real-scene data and virtual simulation data will be constructed. Leveraging transfer learning and data augmentation techniques, the limitation of high collection costs for real data will be addressed, while research on multi-agent collaborative systems will be conducted.

Second, real-time perception and dynamic planning modules will be introduced. Combined with visual sensors and force feedback devices, part status, human operation trajectories, and robot workload during the assembly process will be captured. Through the Action Chunk Transformer framework, dynamic adjustment of assembly sequences will be realized.

Finally, a general assembly sequence generation model based on large language models (LLMs) will be explored. In the pre-training phase, the model will learn the common constraints of different assembly tasks. When confronted with new tasks, only a small amount of task descriptions (e.g., part types, assembly objectives) need to be input to quickly generate feasible sequences, which assists the model in reasoning and decision-making in unknown scenarios and significantly enhances its generalization capability.