Thermal Regulation and Moisture Accumulation in Embankments with Insulation–Waterproof Geotextile in Seasonal Frost Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

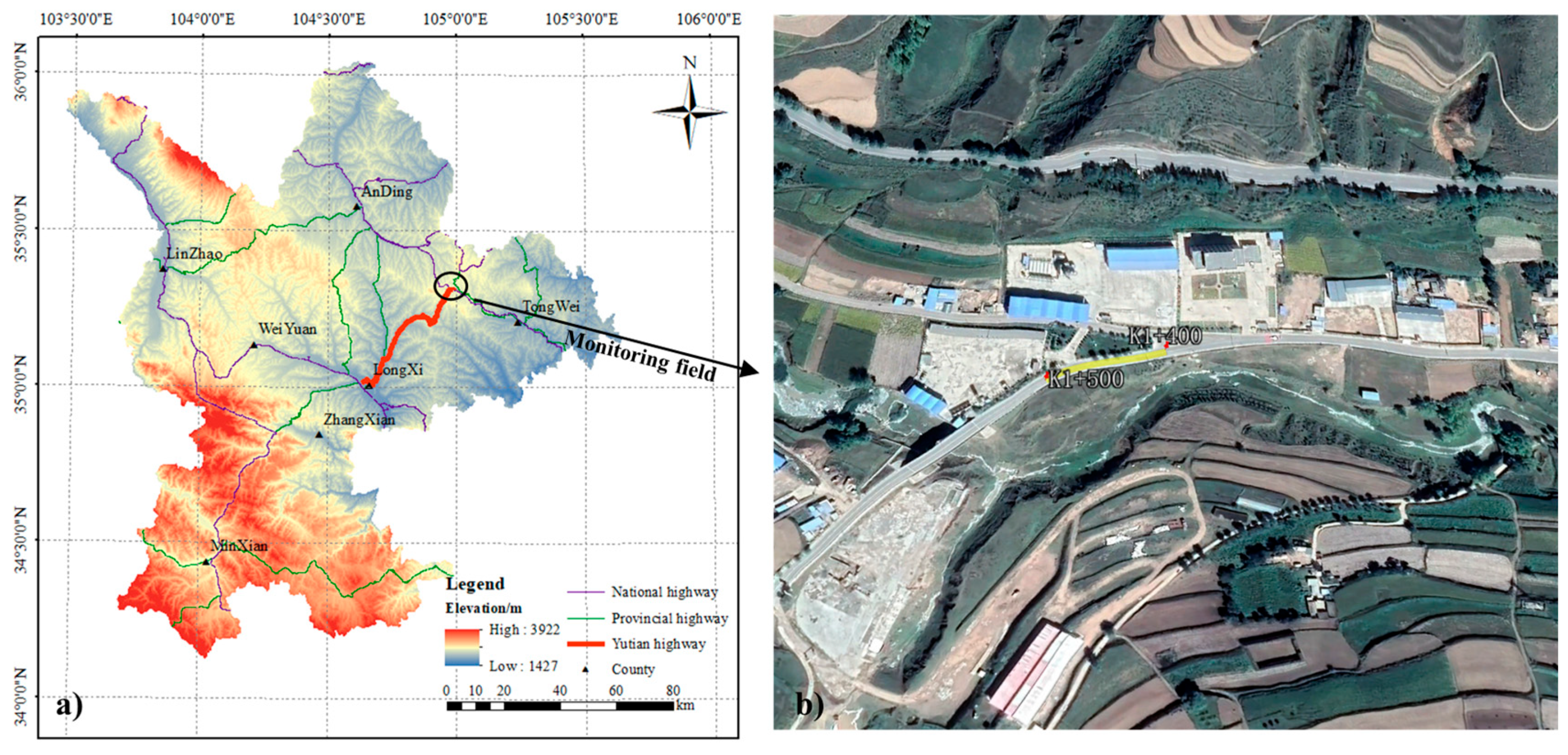

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Experimental Design and Data Collection

3. Results and Analyses

3.1. Variation in Soil Temperature over Time

3.1.1. Analysis of Temperature at Centerline Position

3.1.2. Analysis of Temperature at Shoulder Position

3.1.3. Analysis of Temperature at Toe Position

3.1.4. Distribution of Soil Temperature

3.2. Variation in Water Content over Time

3.2.1. Analysis of Centerline Position

3.2.2. Analysis of Shoulder Position

3.2.3. Analysis of Toe Position

3.2.4. Distribution of Water Content

4. Conclusions

- In the shallow seasonally frozen soil regions, only the surface soil is below 0 °C for a short period time, and the TIB can effectively prevent frost heaving of superficial soil and damage of slope soil. The TIB prevents cold energy from being transferred downward in winter and also prevents heat energy from being transferred downward in the warm season.

- Since the test area has a mid-temperature semi-arid climate with low annual rainfall and high evaporation, and the evaporation of water in the TIE is destroyed by the insulation layer and geotextile, the water content in the embankment is higher than that of the OE. Water accumulates at the toe position in embankments.

- For embankments in the seasonally frozen ground, especially in dry areas, more consideration should be given to the damage to the embankment caused by the dry–wet cycle or soil erosion from acute rainfall in summer. When arranging the TIB, reasonable ditches should be set up at the toe position of the embankment to prevent moisture from accumulating at the toe of the embankment and thus affecting the embankment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y. Frozen Ground of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, D. Glossary of Cryospheric Science; China Meteorological Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, D.H. The Thermodynamics of Frost Damage to Porous Solids. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1961, 57, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, P. Moisture Movement in Soils under Temperature Gradients with the Cold-Side Temperature below Freezin. Water Resour. Res. 1964, 2, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.D. Freezing and heaving of saturated and unsaturated soils. Geology 1972, 393, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guo, F.; Shi, H.; Cheng, M.; Gao, W.; Yang, H.; Miao, Q. A Study of the Insulation Mechanism and Anti-Frost Heave Effects of Polystyrene Boards in Seasonal Frozen Soil. Water 2018, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.I.; Fujun, N.I.; Zhanju, L.I.; Jing, L.U. Progress and prospects of research on frost heave of high speed railway subgrade in seasonally frozen regions. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2019, 41, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.U.; Alex, H.; Brock, C.; Christopher, B.; Cynthia, A.C. Investigating the Thermal Performance of Expanded Polystyrene as a Function of Core Temperature using Static and Dynamic Thermal Conductivity Values. In Proceedings of the eSim 2018: 10th Conference of IBPSA, Montréal, QC, Canada, 9–10 May 2018; IBPSA: Montréal, QC, Canada; pp. 568–574. [Google Scholar]

- Basyigit, C.; Özel, C. Thermal insulation properties of expanded polystyrene as construction and insulating materials. In Proceedings of the 15th Symposium in Thermophysical Properties, Boulder, CO, USA, 22–27 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Tian, Y. Numerical studies for the thermal regime of a roadbed with insulation on permafrost. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2002, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghi, N.T.; Hashemian, L.; Bayat, A. Seasonal Response and Damage Evaluation of Pavements Comprised of Insulation Layers. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2019, 12, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Yan, H.; Yao, J.; Cui, Y.; Chen, F. Engineering Test Research of XPS Insulation Structure Applied in High Speed Railway of Seasonal Frozen Soil Roadbed. Procedia Eng. 2016, 143, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hou, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, S. The thermal effect of strengthening measures in an insulated embankment in a permafrost region. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2015, 116, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başoğul, Y.; Demircan, C.; Keçebaş, A. Determination of optimum insulation thickness for environmental impact reduction of pipe insulation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 101, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daşdemir, A.; Ertürk, M.; Keçebaş, A.; Demircan, C. Effects of air gap on insulation thickness and life cycle costs for different pipe diameters in pipeline. Energy 2017, 122, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Naterer, G.F. Heat transfer in a tower foundation with ground surface insulation and periodic freezing and thawing. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2010, 53, 2369–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Investigation of the Insulation Effect of Thermal Insulation Layer in the Seasonally Frozen Region Tunnel: A Case Study in the Zuomutai Tunnel, China. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 4978359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Luo, X.; Lai, Y.; Niu, F.; Gao, J. Numerical investigation on thermal insulation layer of a tunnel in seasonally frozen regions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 138, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Wen, Z.; Ma, W.; Liu, Y.; Qi, J.; Wu, J. Long-term evaluations of insulated road in the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2006, 45, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZhiQiang, L.; Yuanming, L. Numerical analysis for the ventilated embankment with thermal insulation layer in Qing–Tibetan railway. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2005, 42, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perreault, P.; Shur, Y. Seasonal thermal insulation to mitigate climate change impacts on foundations in permafrost regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2016, 132, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.A. Thaw depths in permafrost soils under road embankments in the presence of heat insulation on slopes. Earth’s Cryosphere 2019, 23, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, B.; Liu, J.; Wang, T.; Shen, Y.; Li, X. Numerical modelling of anti-frost heave measures of high-speed railway subgrade in cold regions. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2017, 141, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wu, Q.; Dong, J.; Luo, J.; Zhang, M.; Ye, Z. Numerical simulation of efficient cooling by coupled RR and TCPT on railway embankments in permafrost regions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 133, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily maximum temperature | 2 | 5 | 13 | 18 | 22 | 26 | 27 | 26 | 20 | 15 | 9 | 3 |

| Daily minimum temperature | −12 | −8 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 13 | 16 | 15 | 10 | 4 | −3 | −10 |

| Temperature (°C) | Depth (cm) | Center | Shoulder | Depth (cm) | Toe | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OE | TIE | OE | TIE | OE | TIE | |||

| Maximum | 15 | 29.44 | 28.38 | 30.07 | 24.34 | 10 | 21.83 | 18.89 |

| 50 | 27.15 | 26.57 | 27.19 | 22.42 | 20 | 20.09 | 18.05 | |

| 100 | 24.56 | 21.59 | 24.65 | 19.34 | 70 | 19.63 | 17.27 | |

| 150 | 22.45 | 19.56 | 22.75 | 17.46 | 120 | 17.83 | 15.89 | |

| 200 | 20.69 | 18.59 | - | |||||

| Minimum | 15 | −0.85 | −2.47 | −5.03 | −4.39 | 10 | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| 50 | 0.81 | 0.21 | −0.96 | −0.71 | 20 | 1.74 | 1.74 | |

| 100 | 2.05 | 3.71 | 0.86 | 2.95 | 70 | 2.33 | 2.33 | |

| 150 | 3.45 | 5.04 | 2.14 | 4.68 | 120 | 4.19 | 4.19 | |

| 200 | 4.85 | 5.63 | - | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, K.; Jin, D.; Zhang, Z.; Mao, Y.; Li, G. Thermal Regulation and Moisture Accumulation in Embankments with Insulation–Waterproof Geotextile in Seasonal Frost Regions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10681. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910681

Zhang K, Jin D, Zhang Z, Mao Y, Li G. Thermal Regulation and Moisture Accumulation in Embankments with Insulation–Waterproof Geotextile in Seasonal Frost Regions. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10681. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910681

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Kun, Doudou Jin, Ze Zhang, Yuncheng Mao, and Guoyu Li. 2025. "Thermal Regulation and Moisture Accumulation in Embankments with Insulation–Waterproof Geotextile in Seasonal Frost Regions" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10681. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910681

APA StyleZhang, K., Jin, D., Zhang, Z., Mao, Y., & Li, G. (2025). Thermal Regulation and Moisture Accumulation in Embankments with Insulation–Waterproof Geotextile in Seasonal Frost Regions. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10681. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910681