1. Introduction

Chronic neck pain (CNP) is a common musculoskeletal condition that significantly impacts quality of life, functional capacity, and healthcare systems worldwide [

1]. Defined as persistent neck discomfort lasting more than three months, CNP affects a substantial proportion of the global population, with prevalence estimates ranging from 16.7% to 75.1% [

2]. Women and middle-aged individuals appear particularly vulnerable to this condition, which frequently leads to reduced daily functioning, diminished productivity, and high rates of comorbidities such as headaches, sleep disturbances, and psychological stress [

3,

4]. Despite advances in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, the underlying biomechanical and physiological mechanisms of CNP remain poorly understood, particularly in relation to scapular stabilizing muscles like the lower trapezius [

5,

6,

7,

8].

The lower trapezius muscle is a critical stabilizer of the scapula, contributing to scapular depression, retraction, and upward rotation [

9,

10]. Dysfunction in this muscle has been strongly linked to scapular dyskinesis, a condition characterized by abnormal scapular movement patterns that increase strain on the cervical spine and exacerbate neck pain. Anatomically, the lower trapezius originates from the spinous processes of the T5-T12 vertebrae and inserts into the spine of the scapula, playing an essential role in maintaining cervical and thoracic spine mechanics [

9,

10]. Studies have consistently reported that individuals with CNP frequently exhibit altered upper trapezius muscle thickness, impaired contraction dynamics, and reduced strength compared to asymptomatic individuals [

3,

11,

12]. However, the role of the lower trapezius muscle in CNP remains unclear because most previous studies have not adequately distinguished between functional parameters (e.g., neuromuscular control, contraction dynamics) and morphological parameters (e.g., muscle thickness). This lack of differentiation limits our understanding of whether structural changes or functional deficits play a primary role in CNP [

7].

Ultrasound imaging is a non-invasive and reliable tool for assessing muscle morphology and function in both clinical and research settings [

13]. Decreased resting thickness may indicate muscle atrophy or disuse, while changes during contraction can reflect functional capacity [

14,

15]. M-mode ultrasound, on the other hand, is designed to capture dynamic changes in muscle behavior, such as contraction and relaxation velocities, which are crucial for understanding neuromuscular efficiency and endurance [

16]. These velocities reflect the rate at which the muscle achieves peak contraction and returns to baseline, providing critical data on the muscle’s performance in real time. Combining RUSI and M-mode ultrasound allows for a comprehensive assessment of muscle morphology and function, which is particularly valuable for studying the lower trapezius in individuals with CNP. Dieterich et al. [

17] showed abductor muscle impairments in patients with chronic hip pain using M-mode ultrasound for assessment.

In addition to imaging, previous research demonstrated that the lower trapezius muscle showed decreased muscle strength, and decreased time to onset/latency [

7]. Dynamometry is a precise method for evaluating muscle strength. Handheld dynamometers measure isometric force during maximal voluntary contractions, providing objective data on muscle performance [

18]. Two key parameters, peak force and time to peak force, are particularly relevant in assessing the lower trapezius [

7]. Peak force represents the maximum strength generated during contraction, while time to peak force reflects the speed at which this peak force is achieved, indicating neuromuscular activation and resilience. Impairments in either metric can reveal deficits in muscle function that may contribute to chronic pain states. These assessments are typically performed during standardized tests, such as the prone Y test, which targets the lower trapezius and ensures consistent measurement across participants [

18].

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which the axio-scapular musculature has been assessed with M-mode ultrasound in patients with neck pain. This represents a methodological innovation, as M-mode provides dynamic measures—specifically contraction and relaxation velocities—that cannot be obtained with conventional B-mode ultrasound. Therefore, this study aimed to compare the morphological, functional, and strength-related characteristics of the lower trapezius muscle (such as muscle thickness at rest and during contraction, contraction-to-relaxation ratios, contraction and relaxation velocities, and force production) between individuals with CNP and asymptomatic controls. In addition, the secondary objective was to compare these variables within the CNP group across mild, moderate, and severe disability levels. We hypothesized that functional impairments (contraction and relaxation velocities, peak force) would be observed in individuals with CNP compared to controls, with greater deficits in those with higher disability levels. In contrast, we expected minimal or no differences in morphological measures (muscle thickness).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

This study followed a cross-sectional design, adhering to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [

19], The STROBE checklist is in the

Supplementary Materials. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board (CEID/2022/4/064), and all procedures complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [

20]. Participants provided written informed consent after receiving detailed information about the study aims and procedures.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria and Recruitment

Participants were recruited between October 2022 and October 2024 from the University of Alcalá and through local advertisements (posters and online announcements). For cases, chronic neck pain was diagnosed by a physiotherapist with more than 10 years of clinical experience, following international clinical practice guidelines.

General inclusion criteria for all participants were (1) adults aged 18 to 30 years, (2) sufficient reading and oral comprehension capacity to complete self-reported questionnaires, and (3) providing signed written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. General exclusion criteria included (1) pregnancy, (2) previous traumatic injury or surgery in the cervical spine or upper extremities, (3) conditions impairing functional test performance, (4) red flags such as infections, bone fractures, or malignancies, (5) significant upper limb asymmetries requiring medical attention, (6) peripheral or central neuropathies or cognitive, psychological, or psychiatric conditions, and (7) undergoing any medical, pharmacological, or physiotherapy treatment during the study period.

Specific criteria for cases included (1) reporting neck pain symptoms persisting for at least 3 months within the last year, and (2) a medical diagnosis confirming chronic neck pain based on clinical examination. Cases with confounding factors such as systemic inflammatory diseases, tumors, or infections affecting the cervical spine were excluded to ensure the specificity of the sample. After meeting these criteria, cases were categorized based on the severity of neck disability as mild, moderate, or severe, using the Neck Disability Index (NDI) [

21].

Specific criteria for controls included (1) absence of neck pain or cervical spine complaints during the last year, and (2) absence of morphological or functional impairments affecting the cervical spine or related musculature. Controls also had to meet all the general inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above. Cases and controls were matched by age, sex, weight, and height to minimize potential confounding variables and ensure comparability between groups.

Cases and controls were frequency matched by age, sex, height, and weight to minimize potential confounding variables.

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size calculation was performed using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.2). The a priori analysis was based on a global between-group MANOVA including three groups (mild, moderate, and severe disability) and eight dependent variables (ultrasound and strength measures). To achieve a statistical power of 0.80 (1-β error probability) and a significance level (α) of 0.05, a medium effect size (f

2(V) = 0.15) was considered. Under these parameters, the required minimum total sample size was 72 participants (24 per group). Our achieved subgroup sizes (n = 29, 25, and 24) exceeded this threshold, ensuring adequate power for the secondary analysis within the CNP cohort [

22].

2.4. Descriptive Variables

Demographic and anthropometric data, including age, sex, height, weight, body mass index (BMI) and side of neck pain (right or left) were recorded for all participants.

2.5. Pain Intensity

Neck pain intensity was assessed using the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) following clinical guidelines for evaluating patients with neck pain. The NPRS is supported in the literature as a highly responsive tool for assessing pain intensity, capable of detecting differences across various levels of severity. The score was calculated as the mean of three measurements: (1) the greatest neck pain intensity during the previous week, (2) the lowest neck pain intensity during the previous week, and (3) the current neck pain intensity at the time of data collection. Scores range from 0 (total absence of pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). Using the mean of these three measurements provides a more precise and reliable estimate of pain intensity, reducing the effects of random variation and ensuring consistency in the data [

23].

2.6. Neck Disability Index

The NDI is a widely used self-reported questionnaire designed to evaluate the level of disability related to neck pain. It consists of 10 items addressing various aspects of daily life, including pain intensity, personal care, lifting, reading, work, headaches, concentration, sleeping, driving, and recreation. Each item is scored on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no disability) to 5 (maximum disability), with a total score ranging from 0 to 50. Higher scores indicate greater levels of neck-related disability. Based on the total score, participants are categorized into five levels of disability: no disability (0–4), mild disability (5–14), moderate disability (15–24), severe disability (25–34), and very severe disability (35–50) [

21].

2.7. Ultrasound Imaging of the Inferior Trapezius Muscle (M-Mode)

A LOGIQ P9 ultrasound system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), equipped with a high-resolution linear transducer (8–12 MHz, 40 mm footprint), was used to measure the thickness and contractile velocity of the lower trapezius muscle. Calibration of the ultrasound scanner was conducted using a standard phantom two days prior to the study to ensure accuracy.

Participants were positioned prone on an examination table, with the head and neck aligned neutrally, and the face resting in the facial cut-out section of the plinth. Arms were placed along the sides of the body with palms facing upward. A pillow was positioned under the abdomen to minimize lumbar lordosis and another under the feet for comfort.

The scanning site was identified through a systematic palpation process. While the participant was seated, the inferior angle of the scapula was palpated and marked with a skin-safe pencil. Simultaneously, the corresponding vertebral level on the thoracic spine was noted. Participants were then positioned prone, and the spinous process of the sixth cervical vertebra (C6) was palpated using the neck extension method, during which C6 becomes less palpable. From this point, the spinous processes were counted downward until the vertebral level closest to the scapular marking was reached. For most participants, this corresponded to the T7-T8 vertebra.

The transducer was first placed centrally and horizontally over the spinous process of the selected thoracic vertebra. This positioning provided a bilateral image of the lower trapezius, resembling a butterfly shape on the ultrasound screen. The probe was then moved laterally towards the inferior angle of the scapula, ensuring that the lateral edge of the spinous process remained visible. The final scanning site was determined to be the most practical point for consistent visualization of the lower trapezius muscle.

Although initial plans included measurements taken at the end of expiration, preliminary observations revealed that breathing did not significantly affect the thickness of the lower trapezius. Therefore, images were acquired without a breathing maneuver, as it introduced potential probe displacement.

Once the lower trapezius of the symptomatic side was clearly visualized, the image was frozen and stored digitally for offline analysis. Measurements of muscle thickness were taken 3 cm lateral to the lateral edge of the spinous process. An additional measurement site, located 2 cm lateral to the spinous process, was also examined to assess whether averaging two measurements would improve reliability [

13,

15].

For each scan, muscle thickness was determined by placing the calipers on the inner edges of the muscle borders to measure the vertical distance. All measurements were performed offline using ImageJ software (version 1.61; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). Images were coded to anonymize participants, and the analysis was conducted one day after image acquisition.

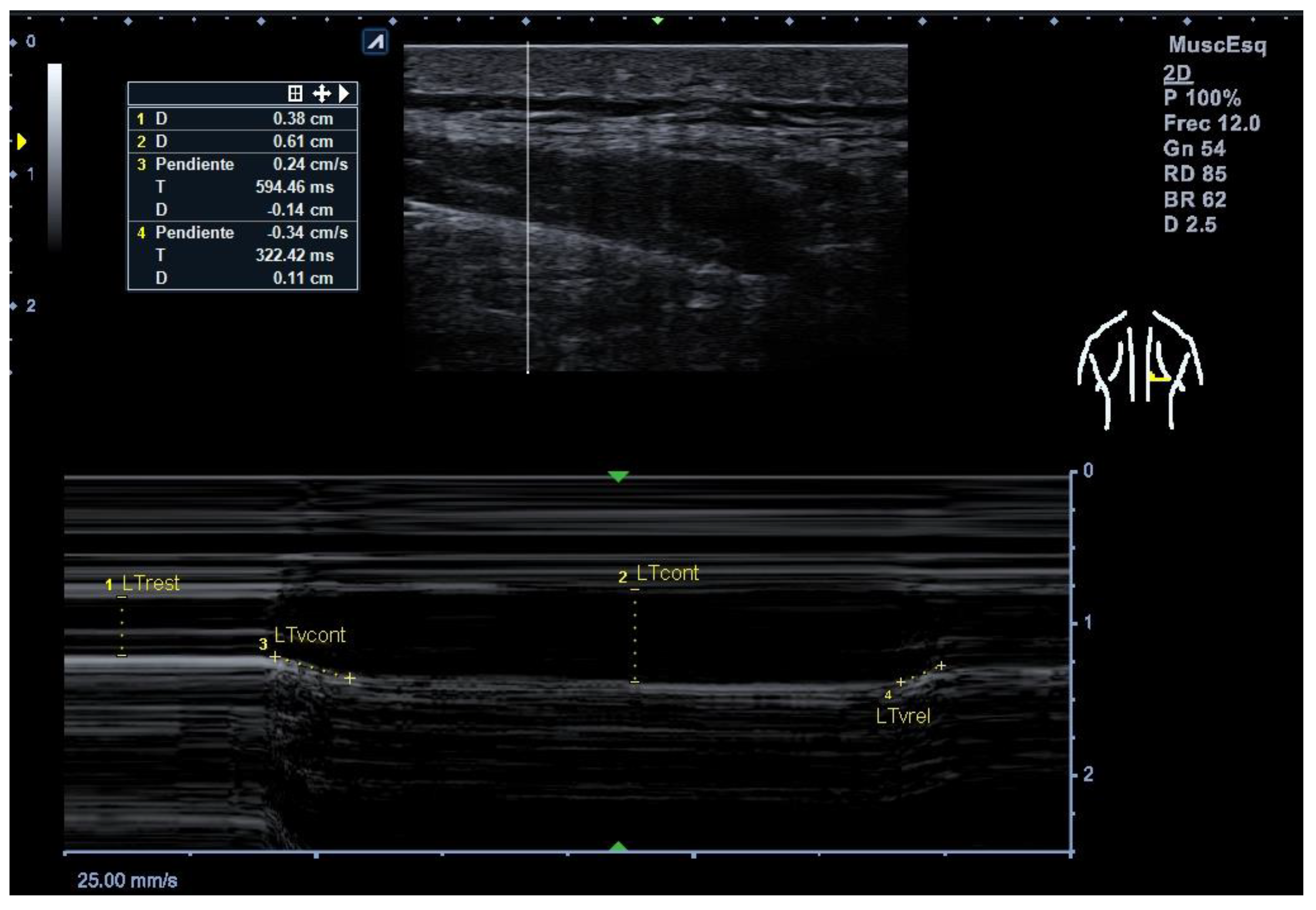

2.8. Thickness Measurements, Velocity of Contraction and Relaxation (M-Mode)

The probe was placed transversely over the lower trapezius muscle belly, visualizing the echogenic layers of the muscle. Three images were captured during end-exhalation to ensure muscle relaxation. During contraction, participants performed a prone Y test, lifting their arm against minimal resistance for 5 s. Three images were taken at the peak contraction. Thickness was defined as the distance between the superficial and deep fascia [

13,

15]. The thickness change in the lower trapezius muscle was monitored using M-mode ultrasound, which allows reliable measurements of muscle thickness and simultaneous measurement of muscle function during demanding activity by assessing the displacement of connective tissue within muscles over time at high temporal resolution [

24]. The contraction ratio was calculated as the thickness during contraction divided by the resting thickness. M-mode ultrasound was also used to measure contraction and relaxation velocities. Participants performed three maximal voluntary contractions while the software calculated the slope from rest to peak contraction (contraction velocity) and peak to baseline (relaxation velocity). Participants received standardized instructions: “Push as hard and as fast as you can and hold for 5 s. Do not shrug or rotate your trunk.” One familiarization (~3 s) trial was followed by three maximal trials, each separated by 60 s of rest. [

16] (

Figure 1). Previous research has demonstrated excellent intra-rater reliability for lower trapezius thickness (ICC = 0.88–0.96) [

13,

15], and for contraction and relaxation velocities using M-mode ultrasound (ICC = 0.82–0.94) [

16].

2.9. Strength Measurement

Strength assessments were conducted using a MicroFET2 handheld dynamometer (Hoggan Scientific, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), calibrated before each test. Muscle strength of the lower trapezius was assessed using a handheld dynamometer. Resistance was applied at the midpoint of the spine of the scapula, corresponding to the anatomical attachment of the lower trapezius muscle. The force was directed along the long axis of the humerus, following a superior and lateral vector. Participants maintained their arm in an elevated position at approximately 140° of shoulder abduction in the scapular plane (Y-position), which optimally engages the lower trapezius muscle while minimizing compensation from adjacent musculature. Three trials were performed, separated by 60 s of rest.

Strength assessments were conducted using a MicroFET2 handheld dynamometer (Hoggan Scientific, Salt Lake City, UT, USA), calibrated before each test. Muscle strength of the lower trapezius was assessed using the standardized Prone-Y test. Participants lay prone on a plinth with the head in a neutral position, trunk and pelvis aligned, and the tested arm positioned at approximately 140° of shoulder abduction in the scapular plane (Y-position), elbow extended, and thumb up, which optimally engages the lower trapezius while minimizing compensation from adjacent musculature. The examiner stood ipsilateral to the tested arm and stabilized their body position using a belt or firm stance to minimize displacement. The dynamometer was applied perpendicularly at the midpoint of the scapular spine, aligned with the anatomical attachment of the lower trapezius, and resistance was directed along the humeral axis with a superior–lateral vector resisting scapular depression and retraction. Participants performed the maximal voluntary contractions following the same standardized instructions and procedure previously described for the ultrasound imaging in M-mode, including one familiarization (~3 s) trial and three maximal trials separated by 60 s of rest. A trial was considered invalid if compensation occurred, such as scapular elevation/upper trapezius dominance, trunk rotation, lumbar extension, elbow flexion, or loss of scapular-plane alignment. Invalid trials were repeated after rest. The mean of three valid trials was used for analysis. Ultrasound images were anonymized and analyzed offline by a rater blinded to group allocation. Although the dynamometer operator followed a standardized protocol and did not access group labels [

25].

Time to peak force and mean force was measured as the rate at which muscle force increased from baseline to peak during the 5 s maximal voluntary contraction test. Specifically, it was calculated as the time (in seconds) required to achieve peak force output relative to the initial onset of contraction. Force data were continuously recorded and extracted using specialized proprietary software linked to the handheld dynamometer (Micro-Fet 2). The software allowed for precise identification of the time-to-peak force and provided a graphical representation of force progression over time. Handheld dynamometry of the lower trapezius has also shown excellent reproducibility (ICC = 0.92) [

17].

All ultrasound and dynamometry assessments were performed by a single physiotherapist with more than 7 years of experience in musculoskeletal imaging and strength testing.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted to evaluate the differences between control and case groups, as well as among subgroups of cases stratified by NDI values (mild, moderate, and severe). First, the assumption of normality for all continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Independent t-tests were applied to compare descriptive variables and assess differences between the control and case groups for continuous variables.

To evaluate differences across the three NDI subgroups (mild, moderate, severe) within the case group, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed, with dependent variables defined a priori as contraction velocity, relaxation velocity, peak force, mean force, time to peak force, contraction ratio, and muscle thickness (rest and contraction). Pillai’s Trace, corresponding F-values, degrees of freedom, and effect sizes are reported. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Bonferroni correction, and the significance level for these comparisons was adjusted to p = 0.017 to account for multiple comparisons.

Effect sizes were interpreted for both the MANOVA and post hoc analyses. Partial eta squared (η2p) was used to quantify the proportion of variance explained by the grouping factor. For the MANOVA, η2p values ranged from small (0.02) to moderate (0.28), depending on the variable. Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated for pairwise comparisons, with values interpreted as small (0.2), moderate (0.5), or large (0.8). These measures provided additional insights into the magnitude of the observed differences. Results are reported as mean differences with 95% confidence intervals, in addition to p-values. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 29 for Windows), with the level of significance set at 0.05.

3. Results

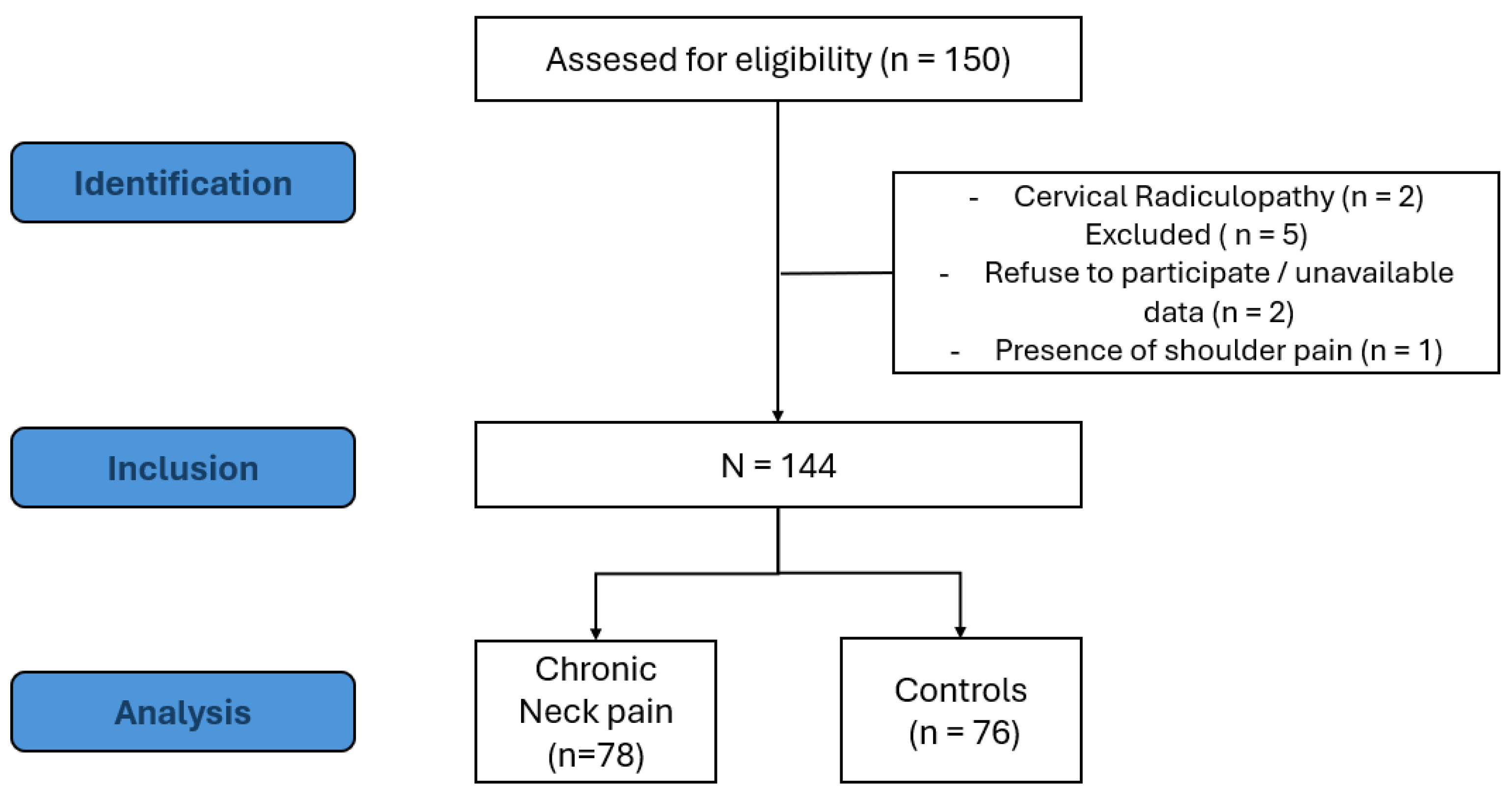

One hundred and fifty volunteers were assessed for eligibility in the study. Finally, a total sample of 144 participants (control group = 76 and cases group = 78) were included in the study, with 53% were male, and 47% were female, with an equal distribution of sexes between the control and neck pain groups, each comprising 26.4% of the total sample for both males and females (

Figure 2). No statistically significant differences were observed between the groups for descriptive variables, including age, height, weight, or BMI (

p > 0.05) (

Table 1).

Participants in the neck pain group exhibited a mean pain intensity of 5.72 ± 1.38 on the VAS scale, indicating moderate to high levels of perceived pain. Additionally, their NDI scores averaged 14.68 ± 8.09, reflecting moderate impairment related to cervical discomfort.

Significant impairments were found between cases and control in contraction velocity (

p < 0.001), relaxation velocity (

p = 0.038) and peak force of lower trapezius strength (

p = 0.043) showing medium-to-high effect sizes. The contraction ratio showed non-significant differences (

p = 0.060) with medium effect sizes. In contrast, muscle thickness, mean force, and time to reach maximum force exhibited no significant differences (

p > 0.05) and had low effect sizes (

Table 2).

The MANOVA found a statistically significant difference in the lower trapezius ultrasonographic (thickness and velocity) and muscle strength measurements between the three groups of cases divided by NDI scores (Pillai’s Trace = 0.401, F (18, 136) = 1.897,

p = 0.021, and η

2p = 0.201). The results of the between-subjects effects analysis revealed that the contraction ratio of the inferior trapezius exhibited statistically significant differences between groups (F = 4.465,

p = 0.015). However, for the remaining dependent variables, no statistically significant differences were observed. Specifically, the resting thickness of the inferior trapezius approached significance with a

p-value of 0.074, suggesting a potential trend. Similarly, the contracted thickness of the TI (

p = 0.289), contraction velocity (

p = 0.670), and relaxation velocity (

p = 0.322) did not demonstrate significant differences across groups. Measures of force, including mean strength (

p = 0.722), time to reach maximum strength (

p = 0.533), and maximum strength (

p = 0.934), also showed no statistically significant group effects (

Table 2).

Post hoc comparisons revealed significant differences in the contraction ratio of the lower trapezius between the severe and mild disability groups (MD = −0.284, p = 0.015, 95% CI: −0.524 to −0.045), with the severe group showing a lower contraction ratio. However, no significant differences were observed between the moderate and mild disability groups (MD = −0.128, p = 0.545, 95% CI: −0.362 to 0.105), or between the severe and moderate groups (MD = −0.156, p = 0.595, 95% CI: −0.450 to 0.138).

4. Discussion

The present study provides a detailed analysis of the lower trapezius muscle in individuals with CNP, assessing morphological, functional, and strength-related parameters evaluated by ultrasonography and dynamometry. The findings showed that individuals with CNP showed significant impairments in contraction and relaxation velocities, and peak force of the lower trapezius, specifically in those with severe neck disability. However, no significant differences were observed in muscle thickness between groups, supporting those important questions about the interaction between structural and functional deficits in this muscle structure.

The significant decrease reported in contraction and relaxation velocities align with prior research which supports that altered neuromuscular motor control in scapular stabilizers in patients with CNP. Recent systematic reviews have confirmed consistent alterations in scapular stabilizer activation patterns in patients with neck and shoulder disorders, supporting the relevance of our findings beyond individual studies [

7,

8]. Moreover, Bench et al. showed reduced voluntary activation of the trapezius muscle in individuals with neck pain, supporting the relationship with an impaired neuromuscular efficiency and delayed activation patterns [

11]. In this context, Kelson et al. highlighted that individuals with neck-shoulder pain exhibited prolonged muscle activation durations in the trapezius muscle, showing neuromuscular inefficiency [

26]. Additionally, Camargo and Neumann highlighted the role of dysfunctional pattern of scapular stabilizers in increasing the compensatory activation of the upper trapezius, exacerbating muscular imbalance [

9]. The reduced relaxation velocity observed in the present study further emphasizes the chronic tension and fatigue often associated with muscle dysfunction. According to these findings, Madeleine et al. identified impaired surface electromyography connectivity in subjects with neck pain during functional tasks, showing an inefficient neuromuscular communication [

27].

The significant reduction in peak force of the lower trapezius in individuals with CNP plays a critical role in maintaining scapular stability and decreasing cervical spine load. A lower trapezius weakness impairs force generation during scapular stabilization tasks contributing to increased cervical strain [

18]. The results of the present study support this by reporting that strength deficits are most pronounced in individuals with severe disability, reinforcing the importance of targeted interventions for those individuals with functional conditions. Interestingly, while peak force was reduced, mean force and the time to achieve peak force did not show differences, suggesting that maximal force production is impaired, but the rate of force generation remains preserved. These findings are in contrast with Michener et al., who observed delayed force production in patients with shoulder pain, reporting differences in neuromuscular activation patterns [

25].

Regarding the RUSI assessments, a key finding in this study is the absence of differences in the lower trapezius muscle thickness between cases and controls, despite clear functional impairments. This aligns with O’Sullivan et al. hypothesis who argued that functional deficits could occur without measurable atrophy in the early stages of dysfunction [

13] Similarly, Zakharova-Luneva et al. reported altered behavior of the lower trapezius muscle in patients with neck pain and scapular dysfunction, highlighting that changes in the muscle function may not always be related to structural atrophy [

28]. Our findings support the hypothesis that functional impairments may precede structural atrophy, which may not always be detectable in early or less severe cases. In contrast with the findings of the present study, prior authors showed that patients with neck pain showed reductions in the lower trapezius muscle on the painful side compared with healthy controls [

14]. These results may reflect differences in study populations, assessment methodologies or the chronicity of neck pain, suggesting that while structural changes can be presented, they may not be present across all the individuals with neck pain, particularly in early or less severe cases. The discrepancies with previous studies reporting atrophy of the lower trapezius may be explained by methodological differences (e.g., B-mode vs. M-mode ultrasound, sample chronicity, or side selection). Although both imaging modes have been shown to be equally reliable for assessing muscle thickness [

24]. Regarding the differences in contraction ratios between individuals with severe and mild disability, supporting the dose–response relationship between lower trapezius dysfunction and increasing levels of neck disability.

4.1. Clinical Implications

The findings of this study provide important clinical implications for the management of CNP. The observed functional impairments, such as reduced contraction and relaxation velocities and a decrease in the peak force in lower trapezius muscle, highlight the need for targeted interventions aimed to restoring neuromuscular efficiency and muscle strength. Additionally, RUSI evaluation revealed that, despite clear functional impairments, no thickness differences were observed in the lower trapezius muscle, supporting that structural changes may not always accompany early neuromuscular conditions, reinforcing the clinical value of using ultrasonography tools for the detection functional deficits before overt atrophy occurs. Patients with neck pain could benefit from specific exercises such as prone Y-raises, prone rows, and face-pulls may be considered because they selectively activate the lower trapezius while minimizing upper trapezius compensation, but randomized trials are needed before firm recommendations can be made [

9,

25]. In addition, the observed reduction in contraction velocity (0.22 cm/s; d = 0.61) and peak force (1.2 kg; d = 0.33) suggests deficits of moderate magnitude, which may be clinically relevant, although specific thresholds for lower trapezius performance remain to be established. Future research should define minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) for ultrasound and strength parameters to determine the thresholds that justify clinical intervention.

4.2. Limitations and Future Lines

Several limitations should be acknowledged in the present study. Participants were recruited by convenience sampling, which may limit generalizability. The cross-sectional design precludes causal inference and only allows associations to be observed. The relatively narrow age range of our participants (18–30 years) limits the generalizability of the findings to older populations, in whom CNP is also highly prevalent. Ultrasonography provides a reliable muscle assessment of the muscle thickness in static and dynamic moments; however, this approach does not capture all aspects of neuromuscular performance, such muscle recruitment or fatigue during tasks performance. Electromyography (EMG) was not used to confirm recruitment patterns, which could complement ultrasound findings. Future research should include longitudinal designs to clarify whether functional deficits precede structural atrophy, and randomized controlled trials combining ultrasound and EMG with functional outcomes to evaluate rehabilitation programs.