1. Introduction

Positional plagiocephaly is a common condition in infants, characterized by asymmetrical posterior occipital flattening as a result of external mechanical pressure. In more severe cases, asymmetry appears in additional cranial areas, which affects the facial structure [

1]. Congenital Torticollis is a congenital cranial asymmetry due to unilateral shortening or tension in the sternocleidomastoid muscle and is often associated with plagiocephaly [

2].

The prevalence of plagiocephaly has increased significantly since 1992, due to an American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) directive to lay infants in a supine sleeping position, aimed at reducing the rate of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In recent years, the reported rate of plagiocephaly for infants aged up to a year is 16–48% [

1]. Recent international reports of plagiocephaly prevalence vary greatly, from 6.3% prevalence reported in China, 2021 [

3] to 46.3% in India, 2024 [

4].

Not only is plagiocephaly a noticeable aesthetic condition, it may be associated with developmental delay. A systematic review from 2017 [

5] found a significant relationship between plagiocephaly and developmental delays in early childhood; a finding that stresses the importance of early detection. An additional current study, testing the effect of plagiocephaly on cognitive and academic skills amongst 336 school-aged children, found that the parameters were connected. Children who had suffered from medium or severe plagiocephaly in the past received lower grades in most measures as compared to children in the control group [

6]. Although it remains unclear which condition occurs first, it is likely that plagiocephaly is a marker for potential developmental concerns.

This implies that plagiocephaly can cause permanent cranial and facial deformation, and that the condition can be correlated to various kinds of developmental delays. These findings underscore the need for early diagnosis and treatment referral as required, which would aid in the detection of motor delays and the long-term aesthetic and/or developmental implications.

Diagnostic methods for plagiocephaly include a broad range of methods, most of which are complex and not clinically applicable. Some of these methods are anthropomorphic [

7,

8], and others are based on imaging methods such as X-ray, CT, MRI [

9], and laser scanning [

10]. These methods are difficult to administer due to equipment costs and the measurement process, which requires prolonged static positioning of the infant.

The Argenta classification emerges as the diagnostic tool that is best suited for clinical use, as it is the most straightforward, efficient, and cost-effective [

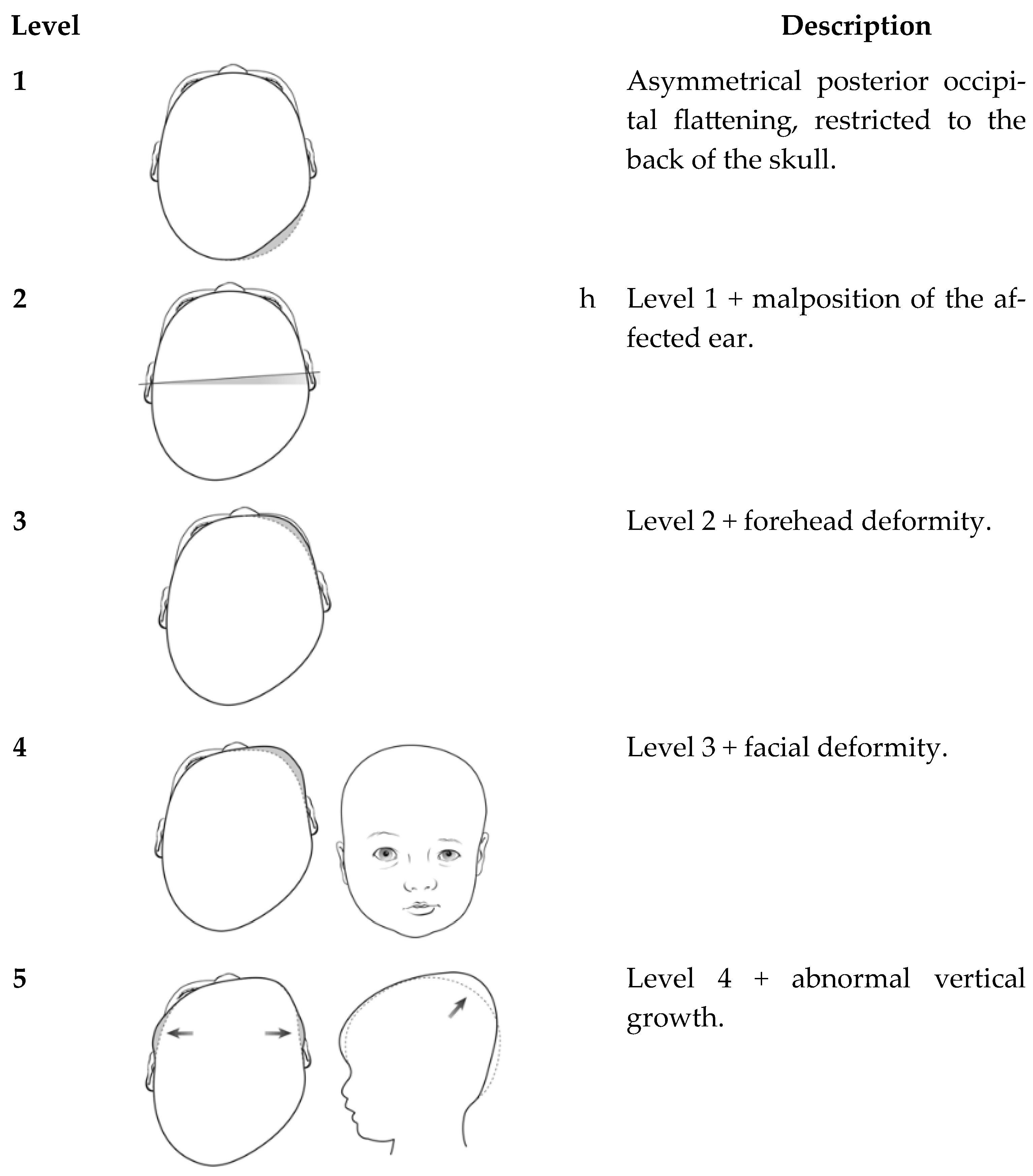

11]. However, there is little knowledge regarding the validity and reliability of the Argenta classification, emphasizing the need for further research on its clinical value. The Argenta classification, first designed by Prof. Louis Argenta in 1998, is an observational diagnostic tool that provides five classification levels for plagiocephaly based on cranial asymmetrical characteristics. The severity level, according to the Argenta classification, is determined by observing the infants from the front, back, side, and above, noting the absence or presence of specific characteristics (

Figure 1). This classification tool enables the detection and monitoring of plagiocephaly, and is aimed at standardizing clinical appraisal, according to the extent of cranial deformation [

12].

Two prospective studies supported therapeutic validity. They followed up infants with plagiocephaly who were treated with a helmet [

11,

13]. Another retrospective study [

13] tested changes in cranial structure in 1050 infants who had been treated for plagiocephaly with a passive helmet (i.e., without applying cranial pressure). These validity studies evaluated how accurate the Argenta classification was in monitoring the plagiocephaly severity level change, using this tool in every follow-up appointment. In almost all cases, they found a gradual decrease in plagiocephaly severity according to the Argenta classification. In another study, researchers conducted a retrospective 12-year review of the files of 4483 infants diagnosed with plagiocephaly according to the Argenta classification [

11]. Similarly to the findings of Couture et al. [

13], Branch et al. [

11] found that the lower the severity as defined by Argenta, the higher the chances for complete correction, the younger the age at which this was achieved, and the shorter the treatment duration. They concluded that the Argenta classification enables a valid classification of infant cranial deformity, aids in choosing suitable treatment, and additionally provides an estimate of the time required to correct the condition. These clinical validation studies are the main evidence for validity. Extensive literature searches have not identified evidence for construct validation against a gold standard. Imaging techniques may serve as a comparative gold standard for future validation research. The reason such evidence was not found may be that scanning and imaging require the infant to remain in a lengthened static position, which often may necessitate sedation. Given the ethical concerns associated with sedating infants for non-therapeutic purposes, this procedure may have been considered unjustified. This barrier to imaging plagiocephaly enlightens the importance of further research and development of clinical methods such as the Argenta.

Upon review of the literature for a study that tested Argenta classification’s reliability, only one reliability study was found [

14]. The study was conducted in Holland for 20 infants aged up to one year, observed by raters from three professions– pediatricians, developmental physiotherapists (physical therapists), and manual therapists. Intra-tester reliability was only tested for 16 infants and only by the manual therapists. The study found medium inter-tester reliability (mean weighted κ = 0.54), and medium to high intra-tester reliability (mean weighted κ = 0.60–0.85) [

14]. The researchers concluded that the classification is a very user-friendly method, but that it is only moderately reliable. Therefore, they recommend continuing research before the method can be applied for clinical use [

14].

Despite the clinical advantages of using the Argenta classification, it requires further proof of reliability to support its clinical application. This study’s findings will lead to operative conclusions regarding the practical efficacy of the Argenta classification in the clinical field.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Population

The study cohort included infants aged between 6 weeks and 12 months, diagnosed as suffering from torticollis or plagiocephaly by the treating physician or by a pediatric physiotherapist. The study’s population did not include infants who suffered from central nerve system damage, genetic disorders, metabolic disorders or craniosynostosis.

3.2. Research Team and Training

The research team included three registered developmental physiotherapists, each with practical experience in the approximate range of 10–16 years. A theoretical and practical training process took place to prepare the research team for evaluating plagiocephaly severity using the Argenta classification. A senior plastic surgeon who specializes in plagiocephaly, and who was part of the original Argenta classification research team, led the training. Instruction included a theoretical tutorial and hands-on practice, followed by a pilot study of reliability testing, during which the researchers practiced evaluating plagiocephaly severity level using the Argenta classification, using three-dimensional cranial pictures of 30 true infant cases. Team training duration was 8 hours in total.

3.3. Study Protocol

The study was set up at Child Development units, Clalit Health Services, Afula, and Tiberias, Israel. The investigating physiotherapists screened candidates from infants referred to physiotherapy in the Child Development units. For each infant that complied with the study’s inclusion criteria, a process was initiated with his or her parents to obtain informed consent according to the Helsinki Committee specifications approved by the Clalit Health Services review board.

To test inter-rater reliability, two developmental physiotherapists individually assessed plagiocephaly severity for the same infant on the same day (Rater 1 and Rater 2). Tests were separate, and each rater was not aware of the other’s reports. Where raters were uncertain between adjacent levels, assigning an intermediate severity level (e.g., 1.5) was permitted.

Repeated assessments by the same rater were also conducted to determine intra-rater reliability. The intra-rater researcher, Rater 1, conducted repeated assessment of plagiocephaly severity for the same infant within a maximum of seven days from their first assessment. Each child was rated according to a severity level of 1–5. A score of 0 was recorded if no cranial asymmetry was observed.

The observations were conducted during routine follow-ups in the child development outpatient clinic. The Argenta evaluation process took 3 to 5 min; therefore, it did not interfere with physiotherapy sessions. The study received approval from the Ethical Committee for Experiments in Humans of Haifa University (Approval no. 256/19) and was also approved according to the Helsinki Committee specifications, as adopted by Clalit Health Services (Study approval no. COM-117-18).

3.4. Statistics

The sample size was statistically determined in advance for a study with an ordinal variable. The assumed distribution was as follows: Level 1–40%; Level 2–30%; Level 3–15%; Level 4–10%; and Level 5–5%. Study parameters were set as follows: Power = 80%; Kappa = 0.85; α = 0.05; H0: K < 0.10 vs. Ha: K > 0.10; and sample size N = 42. This calculation was performed by R computer program’s irr software package, function N2.cohen.kappa [

15]. The primary result measure was plagiocephaly severity according to the Argenta classification.

3.5. Data Processing and Statistical Methods

Weighted kappa analysis was used as an index of inter-rater reliability and intra-rater reliability. This analysis attributes different weights to each category according to incompliance rates. That is, the incompliance index is influenced by the squared disparity between the categories and complete compliance. Researchers used the R-kappa2 function of the irr software package (irr: inter-rater reliability) [

16]. Univariate analysis was conducted, using Wilcoxon and Kruskal–Wallis tests, and Spearman correlation testing was applied. These measures aimed to test the relationships between plagiocephaly severity according to the Argenta classification and the following characteristics: gender, age, side of flattening, birth week, birth order, type of delivery, and the AIMS (Alberta Infant Motor Scale) score.

4. Results

Forty-two infants between the ages of 6 weeks and 12 months participated in the study, with an average age of 3.05 ± 5.54 months, of which 24 were males and 18 were females. Thirty suffered from right-occipital flattening and ten suffered from left-occipital flattening. Twenty-six were delivered via vaginal birth, three via instrument-assisted birth, and thirteen via Caesarean section. Primiparity was observed in 24 cases, whereas in 18 cases, the birth occurred in multiparous mothers. Fourteen participants were defined as premature (born before the 37th week of pregnancy), and twenty-eight were carried to term. The average percentile for the AIMS score for motor development was 22 ± 35, which represents a slightly lower average than that of infants with standard functional development. Ten of the forty-two tested infants (23.8%) scored in the tenth percentile or lower in the AIMS diagnosis [

17]. This percentile represents a motor delay that requires physiotherapy (all participants were referred to physiotherapy).

Frequencies for severity rates as observed by the two raters by the Argenta classification are depicted in

Table 1. The Argenta classification did not define a category for cases where no asymmetry is observed. Our raters identified two cases as symmetric, and therefore we decided to add a zero score to classify them (

Table 1). As shown, the most frequent severity rated by rater 1 in the reliability test was 4 (28.6%), as opposed to the most frequent severity rate of 3 (33.3%) given by rater 2. The table shows that the majority of tested infants (74%) rated 2, 3, or 4, and the minority (26%) received rates of 0, 1, or 5.

The inter-rater reliability analysis revealed excellent agreement between raters (κ = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.74–0.96,

p < 0.0001). The kappa coefficient of 0.85 indicates near-perfect agreement according to the Landis and Koch criteria [

18,

19], with a standard error of 0.05 and a Z-score of 5.53, demonstrating statistically significant reliability.

Table 2 displays the weighted Kappa results for inter-rater reliability, and

Table 3- for intra-rater reliability according to the various severity levels. Beyond the desire to test the general reliability of the Argenta classification, there was also an interest in separating severity levels to understand whether any specific category particularly affected reliability (positively or negatively). To this end, a separate reliability analysis was also performed for each severity level. The rating compliance was very good according to the categories defined by Altman [

20], both between two raters (κ = 0.85,

p < 0.0001) and for repeated tests by the same rater (κ = 0.90,

p < 0.0001). These results corroborate the Argenta classification of plagiocephaly severity.

As shown in

Table 2, inter-rater reliability was highest for Level 1 (κ = 0.81,

p < 0.0001), and the lowest inter-rater reliability was for observed for Level 4 (κ = 0.39,

p < 0.012). The intra-rater reliability (

Table 3) was highest for Level 4-5 (κ = 0.9–1,

p < 0.0001), and the lowest for Level 3 (κ = 0.41,

p < 0.044).

Frequencies for severity rates, as observed at two different times by Rater 1, according to the severity levels, are described in

Table 4. As shown, the most frequent severity rated at time 1 was 4 (33.3%), and the most frequent at time 2 was level 2 (33.3%). The table shows that the majority of tested infants (83.4–87.5%) rated 2, 3, or 4, and the minority (12.5–16.6%) received rates of 1 or 5.

The intra-rater reliability analysis revealed excellent agreement between raters (κ = 0.9, 95% CI: 0.80–0.99,

p < 0.0001) [

18,

19], with a standard error of 0.05 and a Z-score of 4.4, demonstrating statistically significant reliability.

In addition to the reliability analysis, the correlations between the Argenta rate and the other collected measures were examined. No significant correlations were found between plagiocephaly severity as determined by the first rater, and the following parameters: gender, age, side of flattening, birth week, type of delivery and the AIMS percentile (p > 0.05).

5. Discussion

The results of the current study exhibited very good inter-rater and intra-rater reliability for rating plagiocephaly severity according to the Argenta classification. An additional finding indicates that the highest degree of reliability occurred in Level 1, followed by Level 0. The high inter-rater reliability found for the milder levels is likely due to there being fewer degrees of freedom when rating these types. Since only one characteristic is necessary to rate an infant as Level 1, the potential for error is minimal. The lowest inter-rater reliability appeared for Level 4, followed by Level 3. The highest intra-rater reliability score was achieved for Level 5 (κ = 1, p < 0.0001). The extraordinarily high reliability score noted for this level was due to the fact that only two subjects were rated as Level 5 in this study. The prominence and uniqueness of these two subjects affected the inclination towards an identical rating in the repeated observation performed a week later.

Specifically, inter-rater agreement for Level 4 (κ = 0.39) was fair, and intra-rater agreement for Level 2 (κ = 0.52) was moderate. These findings suggest that the current methodology may be limited in its generalization for assessing specific severity levels, and further research is needed.

Amongst the studied subjects, 57% were male, 75% suffered from right-occipital flattening, and 33% were premature babies. Based on these findings, the sample seems similar to the variance observed in the general population. Research shows that plagiocephaly occurs more frequently in males and in premature infants, as opposed to those carried to term, and this study corroborates these findings. Right-occipital flattening is also known to be more common than left-occipital flattening [

21], as displayed in the current study.

Rating reliance was higher in this study than the results reported in the study conducted by Spermon et al. [

14], with mediocre inter-rater reliability (mean weighted κ = 0.54) and high intra-rater reliability (mean weighted κ = 0.60–0.85). It is noteworthy to mention that Spermon et al. interpreted results according to Cohen’s nominal scale [

16], while we chose to verbally interpret the kappa test according to Altman [

20], which represents a stricter measure. Specifically, Spermon found the result of κ = 0.60–0.85 and translated this as ‘high’ reliability, while Altman interprets kappa values of 0.61-0.8 as ‘good’, and only values above 0.81 are considered ‘very good’ [

20]. It is important to highlight the different methods by which the researchers verbally described the quantitative results.

A possible explanation for the higher reliability results found in this study may be the team training process. In the previous study, the rating team underwent a single 45 min training session, with none of the raters having prior experience with the classification. Conversely, the current study provided more extensive training, including group practice and researcher analysis of reliability results during a pilot study. Further research could expand this reliability evaluation to include a prospective study assessing the system’s sensitivity and accuracy in detecting changes over time, with potential application in clinical follow-up.

This intra-rater sample (n = 24) is larger compared to the previous study [

12], which reported a sample size of 16 for intra-rater reliability. In the current study, re-evaluation was conducted solely by rater 1, as not all infants were able to return within one week for re-assessment.

The study found no significant correlations between the first rater’s plagiocephaly severity ratings and the following parameters: gender, age, occipital flattening side, birth week, type of delivery, and AIMS percentile (

p > 0.05). This might be explained by the dynamic nature of the condition; plagiocephaly severity ratings can be diverse when recorded at different times. Deformation severity was rated during a randomly selected checkup for each infant at the institute. Therefore, some rated infants had not yet reached their highest rate of deformity, some had reached this mark, whereas others had shown some improvement. Likewise, current results in the existing literature showed an absence of significant correlations between plagiocephaly severity and the various demographic and clinical parameters collected. Evidence linking plagiocephaly severity to early-life parameters remains limited and inconclusive. Current studies provide only partial support for such associations and establishing definitive links would require larger samples across all severity levels. For instance, one study reported that infants above a severity threshold at one month worsened temporarily at two months but improved by three [

22]. Similarly, a review noted that while some studies suggest deformational plagiocephaly may resolve spontaneously once infants sit independently, others argue that it may worsen without intervention [

1]. These findings highlight the dynamic nature of plagiocephaly in early infancy, offering a plausible explanation for the weak or inconsistent correlations with static factors such as birth characteristics when measured at random time points.

The high inter-rater and intra-rater reliability demonstrated for the Argenta classification system in this study has important clinical implications for reducing diagnostic errors in positional plagiocephaly. Accurate classification through standardized systems like Argenta can help clinicians differentiate between varying severity levels, potentially reducing misdiagnoses that could lead to delayed treatment of conditions like craniosynostosis or unnecessary interventions such as helmet therapy. However, the inter-changing reliability results among severity levels suggests caution is needed when assessing the more severe cases, where more accurate evaluations may be needed, such as scanning.

The main limitation of the intra-rater reliability testing may have been that, in some cases, the rater retained the results recorded the previous week, potentially impacting their decisions during the second observation. This was particularly evident in borderline cases between two levels or in extreme ratings (Levels 0 and 5), which could remain memorable due to their distinctiveness. As part of their physiotherapy, some infants may have received repositioning therapy, which was not controlled. This may have had some therapeutic effect within the <7 day interval exclusive to intra-rater participants. Additionally, based on existing knowledge, the Argenta classification has two general limitations. The first is the need to rate a continuous variable (changes in cranial structure), according to a categorical scale, which obliges raters to choose between two consecutive levels when the observed state resides between the two. Secondly, it only relates to cranial asymmetry distribution and does not include the extent of deformity. Specifically, an infant might be classified as Argenta Level 1 as they only have posterior deformation although they suffer from severe and noticeable plagiocephaly. In other cases, a rating of Argenta Level 4 is assigned due to the widespread deformity, including subtle facial affects; however, the asymmetry is so subtle that parents may remain unaware of the condition. This reliability study analyzed two raters’ results. Further research should examine the reliability between a larger number of raters to increase the generalizability of the findings. The current study’s sample size (N = 42 for inter-rater reliability; N = 24 for intra-rater reliability) limits the generalizability of the findings. While statistically powered for the primary analysis, the small number of cases at certain severity levels (particularly Level 5, with only two cases) restricts conclusions about reliability across all severity categories. The variable reliability observed across different severity levels suggests that larger, multi-center studies are needed to establish definitive reliability parameters before the Argenta classification can be universally adopted in clinical practice.

Future research on changes in plagiocephaly severity during an infant’s first year, as rated according to the Argenta classification, could provide insight into the condition’s spontaneous progress and serve to compare the efficacy of different treatment methods.