From Control to Connection: A Child-Centred User Experience Approach to Promoting Digital Self-Regulation in Preschool-Aged Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How can developmentally appropriate practice be conceptualised and applied as a UX design principle to promote voluntary screen-time self-regulation in preschool-aged children?

- (2)

- How do child development experts evaluate the proposed UX prototype in terms of its emotional resonance and developmental suitability?

2. Review of Related Literature and Applications

2.1. Current Trends in Smart Device Usage and Developmental Impacts on Young Children

- Physical Health

- Cognitive and Language Development

- Social and Emotional Development

2.2. Review of Approaches for Regulating Smart Device Usage

2.2.1. Traditional Parental Control Methods

2.2.2. Co-Use and Guided Mediation

2.2.3. Technology-Based Interventions

- Restrictive InterventionsThese approaches enforce rules automatically through features such as screen-time limits, content blocks, or device locks [36]. While these measures establish clear boundaries, they rely on external control and may impede the development of intrinsic self-regulation. Consequently, children may exhibit resistance or engage in compensatory behaviour once restrictions are lifted [37,38].

- Behavioural Nudging InterventionsBehavioural nudges involve subtle interface adjustments or system cues that guide user behaviour without limiting choice. Examples include grayscale display settings, timed reminders for breaks, or reward mechanisms tied to activity completion [39,40]. These strategies align with user-centred and persuasive design principles; however, their effectiveness often depends on users’ motivation and willingness to engage.

- Environment-Integrated InterventionsThese strategies connect digital regulation with the user’s physical and social context—for example, by establishing screen-free zones, implementing Internet-of-Things-supported sleep routines, or delivering parental education programmes [23]. While such approaches are conducive to long-term behavioural change, they may exert limited immediate impact.

- Artificial-Intelligence (AI)-Based Adaptive Interventions

2.3. Review of Existing Market Solutions for Controlling Smart Device Use

- (1)

- Parent-centred device management applications;

- (2)

- AI-driven automatic monitoring systems;

- (3)

- Child-centred self-regulation applications.

2.3.1. Parent-Centred Device Management Apps

2.3.2. AI-Driven Monitoring and Alert Systems

2.3.3. Summary and Implications

2.4. Limitations of Existing Research and Market Solutions and the Need for a New Approach

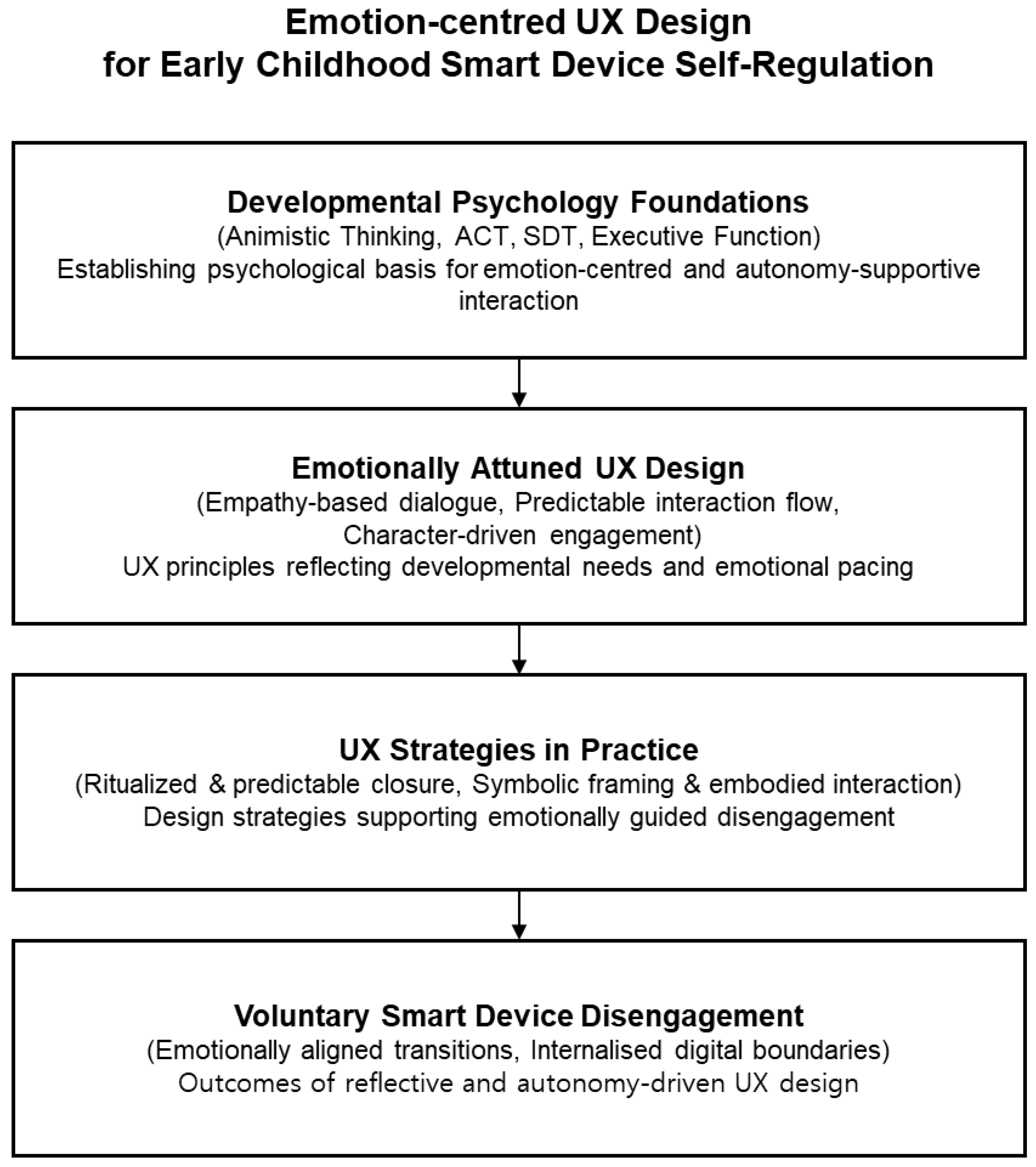

3. Conceptual Framework and System Overview

3.1. Theoretical and Developmental Basis of the User Experience Design

3.1.1. Developmental Challenges in Early Childhood Self-Regulation

3.1.2. Educational Foundations for Emotionally Supportive Interaction

3.1.3. Psychological Frameworks Applied to User Experience Design

3.2. Preliminary System Architecture: UX Design Prior to Expert Consultation

3.3. UX Flow in the Preliminary Prototype

- Initiation: Framing the Experience

- Awareness: Maintaining Engagement and Building Anticipation

- Transition: Voluntary Closure and Emotional Resolution

4. Methods: Expert Consultation and Evaluation Process

4.1. Expert Participants

4.2. Expert Consultation Procedure

4.2.1. Initial Expert Consultation

4.2.2. Follow-Up Expert Consultation

4.3. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Results and Iterative Feature Refinement

5.1. Overview of the Expert-Guided Refinement Process

5.2. Thematic Analysis of Expert Feedback

5.2.1. Shared Themes Across Experts

- (1)

- Emotionally framed interaction;

- (2)

- Persistent visual cues for time awareness;

- (3)

- Developmentally adaptive dialogue;

- (4)

- Ritualised closure and autonomy support;

- (5)

- Process-oriented feedback.

5.2.2. Distinctive Expert Perspectives

5.3. Implementation of Feedback: Feature Refinement

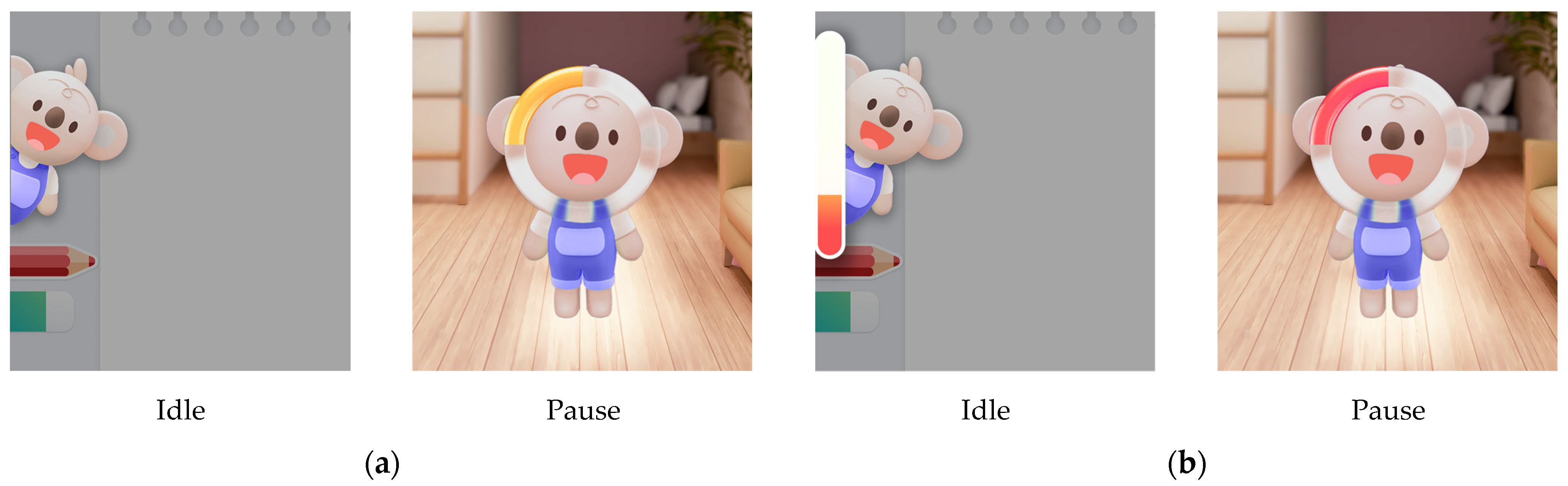

5.3.1. Visual Timer Redesign

5.3.2. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy-Based Dialogue Reframing

5.3.3. Enhanced Session Closure Scenarios

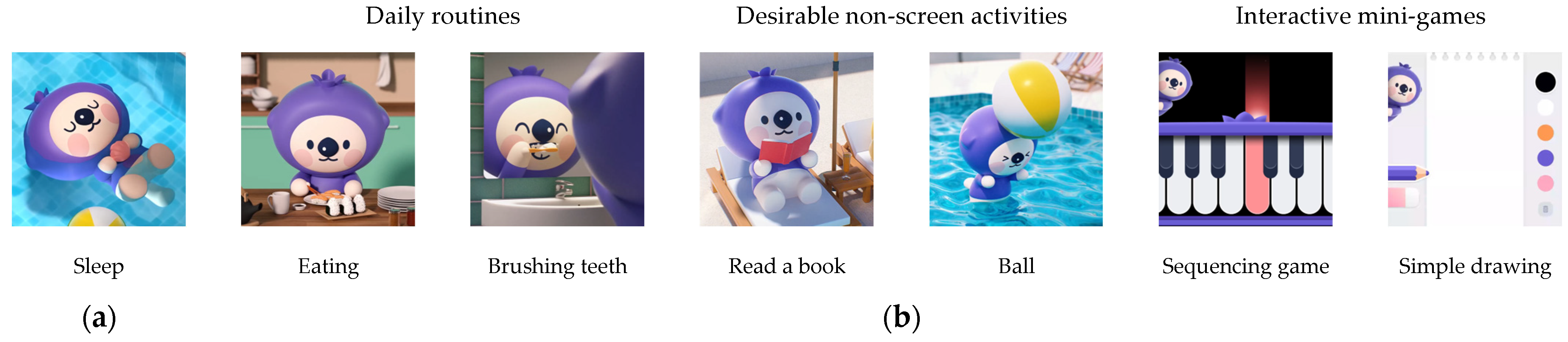

5.3.4. Multimodal and Embodied Interaction

5.4. Expert Evaluation Summary

6. Discussion

6.1. Summary of Key Contributions

- (1)

- Reframing Transitions as Empathetic Interactions,

- (2)

- Supporting Time Awareness through Predictable Visual Cues,

- (3)

- Fostering Intrinsic Motivation through Autonomy Support,

- (4)

- Adapting Modalities to Developmental Needs.

6.2. Design Implications

- Reframing Transitions as Empathetic InteractionsExperts advised against the use of direct commands and externally imposed language—such as ‘promises’—that may place emotional pressure on children or trigger feelings of guilt. Instead, transitions should be presented as relational appeals for assistance or empathy, leveraging on the natural inclination of children to anthropomorphise digital characters. This approach repositions disengagement not as a loss, but as a caring and emotionally meaningful act.

- Supporting Time Awareness through Predictable Visual CuesGiven the limited understanding of time and self-monitoring capacities of preschool-aged children, experts emphasised the need for persistent and intuitive visual indicators of session duration. In response, a colour-coded vertical timer was integrated and displayed continuously throughout the session to provide children with consistent temporal awareness, thereby supporting the development of early executive function.

- Fostering Intrinsic Motivation through Autonomy SupportExperts cautioned against the use of rigid performance metrics and binary success/failure framing, as these may diminish the sense of competence in children. Instead, they recommended providing descriptive feedback that acknowledges effort and incremental progress. They also recommended offering multiple closure options to reinforce autonomy, enabling children to select the modality—e.g., voice, gesture, and physical interaction—that best aligns with their individual preferences.

- Adapting Modalities to Developmental NeedsAs preschool-aged children depend on multiple sensory channels for interaction—particularly given their still-developing literacy skills—experts recommend the integration of multimodal input and output mechanisms. These include tactile, verbal, and physical gesture-based interactions to ensure developmental appropriateness. The inclusion of embodied actions, such as placing the device into a house-shaped charger, was highlighted as a meaningful extension of this principle.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ponti, M. Screen time and preschool children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatr Child Health 2023, 28, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cliff, D.P.; Howard, S.J.; Radesky, J.S.; McNeill, J.; Vella, S.A. Early childhood media exposure and self-regulation: Bidirectional longitudinal associations. Acad. Pediatr. 2018, 18, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Van Kleek, M.; Shadbolt, N. Protection or punishment? relating the design space of parental control apps and perceptions about them to support parenting for online safety. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.B.; Brown, E.R.; Upright, J.; DeRosier, M.E. Enhancing children’s social emotional functioning through virtual game-based delivery of social skills training. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. The child’s Conception of the World; Tomlinson, J., Tomlinson, A., Eds.; Internet Archive: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout, V.R.; Michael, B. The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Age Zero to Eight, 2020; Common Sense Media: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Presta, V.; Guarnieri, A.; Laurenti, F.; Mazzei, S.; Arcari, M.L.; Mirandola, P.; Vitale, M.; Chia, M.Y.H.; Condello, G.; Gobbi, G. The Impact of Digital Devices on Children’s Health: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Guidelines on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep for children under 5 years of age. In Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children Under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Priftis, N.; Panagiotakos, D. Screen time and its health consequences in children and adolescents. Children 2023, 10, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, B.; Li, L.; Cui, Y.; Shi, W. Effects of outdoor activity time, screen time, and family socioeconomic status on physical health of preschool children. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1434936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekkawy, L.; Abdel-Haleem, M. SMART screen exposure and its association with addictive food behavior and sleep disorders in children. what’s beyond the scene? J. Southwest. Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 57, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karani, N.F.; Sher, J.; Mophosho, M. The influence of screen time on children’s language development: A scoping review. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2022, 69, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varadarajan, S.; Govindarajan Venguidesvarane, A.; Ramaswamy, K.N.; Rajamohan, M.; Krupa, M.; Winfred Christadoss, S.B. Prevalence of excessive screen time and its association with developmental delay in children aged< 5 years: A population-based cross-sectional study in India. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254102. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Lu, J.; Lin, X. Is screen exposure beneficial or detrimental to language development in infants and toddlers? A meta-analysis. Early Child Dev. Care 2024, 194, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Lin, W.; Zou, M.; Hsu, H.; Lin, W.; Chen, Y. The link between smart device use and ADHD—How can reading and physical activity make a difference? Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, ckad160.837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.N.; Tahir, S.; Kumar, R. The Influence of Early Exposure to Smart Gadgets on Children. Tuijin Jishu/J. Propuls. Technol. 2023, 44, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, J.H.; Cho, S.Y.; Lim, S.M.; Roh, J.H.; Koh, M.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Nam, E. Smart device usage in early childhood is differentially associated with fine motor and language development. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikić, A.; Klein, A.M. Smartphone Use in the Presence of Infants and Young Children: A Systematic Review. Prax. Der Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiatr. 2022, 71, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakranon, P.; Huang, J.-P.; Au, H.-K.; Lin, C.-L.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Mao, S.-P.; Lin, W.-Y.; Zou, M.-L.; Estinfort, W.; Chen, Y.-H. The importance of mother-child interaction on smart device usage and behavior outcomes among toddlers: A longitudinal study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 18, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudron, S.; Di Gioia, R.; Gemo, M. Young children (0–8) and digital technology. In A Qualitative Exploratory Study Across Seven Countries; Joint Research Centre-European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aeni, F.N. The Impact of Gadget Use on Social Interaction for Underage Children; ResearchgGate: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Robidoux, H.; Ellington, E.; Lauerer, J. Screen time: The impact of digital technology on children and strategies in care. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2019, 57, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, D.; Zulkefli, N.A.B.M.; Minhat, H.S.; Ahmad, N. Parental intervention strategies to reduce screen time among preschool-aged children: A systematic review. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 18, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauricella, A.R.; Wartella, E.; Rideout, V.J. Young children’s screen time: The complex role of parent and child factors. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 36, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, J.M.; Ben-Joseph, E.P.; Reich, S.; Charmaraman, L. Parental monitoring of early adolescent social technology use in the US: A mixed-method study. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2024, 33, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, S.; Chu, J.T.W.; Calder, A.J. ‘I tried to take my phone off my daughter, and i got hit in the face’: A qualitative study of parents’ challenges with adolescents’ screen use and a toolbox of their tips. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser Kunz, J.; Grych, J.H. Parental psychological control and autonomy granting: Distinctions and associations with child and family functioning. Parenting 2013, 13, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Khan, M.Z.; Kamal, I. The Role of Parental Mediation Regarding Tablet Usage Among Children. J. Prof. Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 10, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, K.; Wood, E.; De Pasquale, D. Examining joint parent-child interactions involving infants and toddlers when introducing mobile technology. Infant Behav. Dev. 2021, 63, 101568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jago, R.; Edwards, M.J.; Urbanski, C.R.; Sebire, S.J. General and specific approaches to media parenting: A systematic review of current measures, associations with screen-viewing, and measurement implications. Child Obes. 2013, 9, S51–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, S.; Helsper, E. Gradations in digital inclusion: Children, young people and the digital divide. New Media Soc. 2007, 9, 671–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opie, J.E.; Esler, T.B.; Clancy, E.M.; Wright, B.; Painter, F.; Vuong, A.; Booth, A.T.; Newman, L.; Johns-Hayden, A.; Hameed, M. Universal digital programs for promoting mental and relational health for parents of young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 27, 23–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkorian, H.L.; Pempek, T.A.; Murphy, L.A.; Schmidt, M.E.; Anderson, D.R. The impact of background television on parent–child interaction. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyens, I.; Valkenburg, P.M.; Piotrowski, J.T. Developmental trajectories of parental mediation across early and middle childhood. Hum. Commun. Res. 2019, 45, 226–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, K.A.; Hilton, M.; Sutton, E.; Guastella, A.J. Apps and Digital Resources for Child Neurodevelopment, Mental Health, and Well-Being: Review, Evaluation, and Reflection on Current Resources. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e58693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, J.V.; Valença, G. Is My Child Safe Online?-On Requirements for Parental Control Tools in Apps used by Children. J. Interact. Syst. 2024, 15, 823–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.; Hannon, P.; Lewis, M.; Ritchie, L. Young children’s initiation into family literacy practices in the digital age. J. Early Child. Res. 2017, 15, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meates, J. Problematic Digital Technology Use of Children and Adolescents: Psychological Impact. Teach. Curric. 2020, 20, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charan, G.S.; Kalia, R.; Khurana, M.S.; Narang, G.S. From screens to sunshine: Rescuing children’s outdoor playtime in the digital era. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2024, 20, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, C.A.; Baumgartner, S.E. Is life brighter when your phone is not? The efficacy of a grayscale smartphone intervention addressing digital well-being. Mob. Media Commun. 2024, 12, 688–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzikulova, A.; Xiao, H.; Li, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ghassemi, M.; Lee, S.J.; Dey, A.K.; Xu, X. Time2stop: Adaptive and explainable human-ai loop for smartphone overuse intervention. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, C.S.; Raposa, E.B.; Bartolotta, K.; Broner, S.E.; Hareli, M.; Forbes, N.; Christensen, K.M.; Assink, M. The impact of mobile technology-delivered interventions on youth well-being: Systematic review and 3-level meta-analysis. JMIR Ment. Health 2022, 9, e34254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Google. Google Family Link. Available online: https://families.google.com/familylink (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Apple. Apple Screen Time. Available online: https://support.apple.com/en-us/105121 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Telecom, S.K. ZEM Parental Control. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.skt.tjunior (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Uplus, L.G. U+ Child Protection. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.lguplus.mobile.cs (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Kidslox. Kidslox Parental Control. Available online: https://kidslox.com (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- MobileFence. MobileFence Parental Control. Available online: https://www.mobilefence.com (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Bark, T. Bark Parental Monitoring. Available online: https://www.bark.us (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Qustodio. Qustodio Parental Control. Available online: https://www.qustodio.com (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Samsung. Samsung Kids. Available online: https://www.samsung.com/us/apps/samsung-kids (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Amazon. Amazon Kids+. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Amazon-com-Amazon-Kids-FreeTime/dp/B08BPK8X7C (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Pakpahan, F.H.; Saragih, M. Theory of cognitive development by Jean Piaget. J. Appl. Linguist. 2022, 2, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiniker, A.; Lee, B.; Kientz, J.A.; Radesky, J.S. Let’s play! Digital and analog play between preschoolers and parents. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hiniker, A.; Suh, H.; Cao, S.; Kientz, J.A. Screen time tantrums: How families manage screen media experiences for toddlers and preschoolers. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, California, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 648–660. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.; Gweon, G. Supporting preschoolers’ transitions from screen time to screen-free time using augmented reality and encouraging offline leisure activity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 105, 106212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druin, A. The role of children in the design of new technology. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2002, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atance, C.M.; O’Neill, D.K. Episodic future thinking. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2001, 5, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mischel, W.; Ebbesen, E.B.; Raskoff Zeiss, A. Cognitive and attentional mechanisms in delay of gratification. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1972, 21, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Pract. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978; Volume 86. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen, D. The role of pretend play in children’s cognitive development. Early Child. Res. Pract. 2002, 4, n1. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice hall Englewood Cliffs: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Carlson, S.M. Hot and cool executive function in childhood and adolescence: Development and plasticity. Child Dev. Perspect 2012, 6, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Basic device management | ZEM, U+ Child Protection, Google Family Link, Apple Screen Time, Qustodio, MobileFence | Screen time limits, app and website blocking, location tracking, parental monitoring |

| Enhanced online risk detection | Bark, Qustodio | AI-powered content filtering; monitoring of texts, emails, and social media; real-time risk alerts |

| UX tailored for young children | Samsung Kids Mode, Amazon Kids+ | Age-appropriate content, learning-time settings, restricted access to parent-approved apps |

| Remote device control and flexible mode-switching | Kidslox, MobileFence | Remote device locking, mode switching (e.g., allowed/restricted/locked), flexible time-based restrictions |

| Theme | Summary of Expert Insights | Supporting Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Empathy-Based Framing | Experts advised framing transitions in relational terms (e.g., care-based metaphors) rather than as imposed rules. They warned that directive language like “promise” could induce guilt, recommending empathy-driven dialogue to foster a psychologically safe, cooperative interaction. | “The term ‘promise’ should be used with caution, as it can lead to negative framing.” —Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist A “The worst approach is a management and control-centered one that strips children of their rights and completely excludes their perspective.” —Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist B |

| Visual Scaffolding for Time Awareness and Executive Function Support | Experts agreed that persistent, intuitive visual cues are essential for preschoolers with underdeveloped time perception. They emphasized that a continuously visible, color-coded timer functions as a powerful Discriminative Stimulus (DS), helping children anticipate transitions and learn to self-regulate. | “A visual timer is essential. You must enable the children to be able to check it continuously.” —Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist A “The timer... needs to be constantly present in a corner. This is critically important as it functions as what is known in behaviorism as a ‘Discriminative Stimulus (DS).’” —Clinical Psychologist |

| Autonomy-Supportive Transitions | To foster intrinsic motivation, experts argued for providing flexible and gradual supportive pathways to disengagement, rather than just offering a choice. This is especially critical for children with low impulse control, enabling them to feel a sense of agency and accomplishment. | “The true goal is for the child to stop by their own decision... and to actually feel good about it.” —Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist A |

| Growth-Oriented Feedback to Reinforce Competence | Experts strongly advised against binary success/failure metrics. They advocated for a process-oriented approach that visualizes growth over time (e.g., shorter disengagement latency) and provides immediate positive reinforcement to foster a sense of competence. | “It’s not about a binary Yes/No distinction... if the time it took to disengage has significantly decreased... then that is also development and growth.” —Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist A “When they do well, it would be good if the whole screen changes to show ‘Great job!’... Things that visually ascend, or a star that spins and lands on their head... Since this is an app for building good habits, using more of these elements to bring out more behavioral responses from children would be great.” —Clinical Psychologist |

| Personalization Based on Developmental Needs | Experts unanimously agreed that a one-size-fits-all approach is insufficient. They recommended personalizing the interaction by adapting the character’s persona and the level of support to the child’s individual temperament (e.g., based on the TCI model) and regulatory needs. | “However, for children with significant impulse control issues or overdependence, a different approach (such as a reward system) might be necessary. They would likely need more robust rewards... The current reward system is actually quite weak in that context.” —Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist B “If possible, it would be good to group children into about three levels at the beginning, and provide more flexible opportunities for those with impulse control issues or overdependence.” —Clinical Psychologist |

| ACT Framework | Before Consultation | After Consultation |

|---|---|---|

| Accept & Acknowledge | Dialogue: “[Child’s name], it’s time for me to go now. We made a promise, remember?” Limitation: Focused on reminding the child of a rule, failing to acknowledge or accept their feelings. | Dialogue: “[Child’s name], I know it’s disappointing, but it’s time for me to rest. I’m sad about it, too.” Refinement: Implements ‘Acceptance’ by first verbalizing the child’s emotion, creating an empathetic foundation. |

| Connect to Value | Dialogue: “If you don’t keep our promise, I might have less energy to play next time.” Limitation: Motivates through a negative consequence prospect, not a positive value. | Dialogue: “After I get some rest, I’ll have even more energy to play with you next time!” Refinement: Links the present action to a more desirable future state, motivating the child with a positive goal. |

| Encourage Committed Action | Dialogue: Binary success (“Thanks!”) or failure (Sad expression) responses. Limitation: Lacks supportive scaffolding for a child who is hesitating. | Dialogue: (On hesitation) “It looks like you’re not quite ready. That’s okay, I can wait a little longer.” (On success) “Thank you! I’m going to get such a good rest because of you. See you next time!” Refinement: Adds a supportive path for hesitation and provides specific, positive reinforcement for the committed action. |

| Themes | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrist A | Psychiatrist B | Clinical Psychologist | ||

| Emotional Appropriateness | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Developmental Fit | (1) Cognitive | 3.5 | 4 | 3.5 |

| (2) Socio-emotional | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| (3) Language | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Autonomy Support | 3 | 4 | 3 | |

| Symbolic Engagement | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| Usability Flow | 3 | 4 | 3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, D.; Lee, B. From Control to Connection: A Child-Centred User Experience Approach to Promoting Digital Self-Regulation in Preschool-Aged Children. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7929. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15147929

Lee D, Lee B. From Control to Connection: A Child-Centred User Experience Approach to Promoting Digital Self-Regulation in Preschool-Aged Children. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(14):7929. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15147929

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Dayoung, and Boram Lee. 2025. "From Control to Connection: A Child-Centred User Experience Approach to Promoting Digital Self-Regulation in Preschool-Aged Children" Applied Sciences 15, no. 14: 7929. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15147929

APA StyleLee, D., & Lee, B. (2025). From Control to Connection: A Child-Centred User Experience Approach to Promoting Digital Self-Regulation in Preschool-Aged Children. Applied Sciences, 15(14), 7929. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15147929