Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) represents a complex pathological event, which requires continuous and highly specialized territorial interventions. The literature highlights disadvantages faced by people with SCI in accessing local services. This study aimed to investigate the concept of territorial continuity for SCI, reconstructing patients and healthcare professionals’ perspectives, to identify facilitators, barriers and opportunities. Methods: a Focus Group (FG) qualitative study was conducted at Piacenza Ausl; four FGs were carried out; a research team member moderated FGs using thematic guides, while an observer was responsible for noting non-verbal aspects. Meetings lasted between 90 and 120 min and were audio-recorded. Transcript analysis involved the identification of units of meaning, which were grouped into general themes. Results: Final analysis highlighted 435 verbatim, grouped into 21 initial themes, that converged into 5 emerging themes: “SCI continuity as multidisciplinary teamwork”; “The need for rehabilitation as a driver of territorial continuity”; “Reinventing everyday life after SCI”; “Barriers and facilitators”; and “The future of territorial care”. Discussion: Patients and healthcare professionals highlighted the absence of a defined treatment path and the lack of reference points, thus generating disorientation and need for information. Among the proposals, telemedicine, empowering the case manager’s role, promoting specific training courses and rethinking community hospitals were supported.

1. Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a complex neurological condition, characterized by significant impairment for a wide range of bodily systems and functions [1]. SCI can occur following traumatic events, such as road accidents, accidental falls, gunshot wounds and sports-related injuries, or non-traumatic events, including tumors, infections, degenerative diseases or congenital causes [2]. The injury typically evolves as follows: a spinal shock acute phase, with a duration of 3–4 days to 6–8 weeks; a subacute phase (2 months to 6 months); and a chronic phase that occurs 6 months after the injury. Subsequently, clinical presentation stabilizes and the pathology becomes chronic [3].

As for primary damage, SCI triggers a loss of muscle strength, sensitivity, and impairment of visceral functions [4]. Bodily symptoms impact patients’ social and psychological sphere, lowering their participation, quality of life and consequently overall health [5].

Managing chronic SCI (>6 months) presents unique and often complex challenges, with high requests for long-term multidisciplinary care [6]. During hospitalization, healthcare professionals dealing with an SCI patient usually focus on the definition of measurable therapeutic objectives within the short term, often overlooking the challenges which patients face in adapting to a new daily reality after discharge, characterized by individual needs, perplexities and problems [5,7]. Additionally, the amount of assistance and rehabilitation services provided by hospitals or centers is often insufficient to adequately prepare patients and their families for a new life [8]. These assumptions suggest that the involvement of the entire multidisciplinary rehabilitation care team is fundamental for managing these patients, supporting recovery at the best possible level of self-efficacy, and preventing the onset of secondary complications due to chronicity [4].

Currently, the international literature highlights that a universal model for the management of chronic SCI has not been yet developed [5]. This lack of a comprehensive model can result in inadequate support for patients after discharge. Recent studies, indeed, report challenges that patients themselves face in transferring skills from the rehabilitation setting into community life for the purpose of psychosocial reintegration.

Recent studies [9] highlight the difficulty of people with SCI in accessing the same level of primary healthcare as able-bodied people. This insufficient response to their needs is due to multiple factors, such as inaccessible healthcare facilities, lack of appropriate equipment and inadequate training of healthcare professionals in SCI management [8].

The present study employed a qualitative approach using Focus Group Discussion (FDG) to explore the perspectives of patients and healthcare professionals on rehabilitation and care continuity for individuals with chronic SCI. In particular, the research aimed to explore the life experiences of those directly involved in the care process, to identify the challenges and opportunities which characterize the management of chronicity [10]. This study also lays the groundwork for future quantitative research and its premise allows allocation for further investment in the field.

2. Materials and Methods

This was an observational monocentric study with a qualitative design conducted at the Department of Rehabilitative Medicine—AUSL Piacenza, performed by a research group composed of 7 members, of whom two had a Master’s Degree in qualitative research and had already conducted/participated in studies with a qualitative design (Focus Group—FG, ethnography and grounded theory). Two further researchers underwent a training course about FG conduction and analysis.

The study was based on the Focus Group Discussion method (FDG) [10]. FDG represents a qualitative research technique involving a small group of participants guided to discuss a specific theme [11]. A moderator facilitates and guides the discussion, aided by a semi-structured interview or a thematic guide, while an observer takes notes of non-verbal issues.

The research query was framed through the SPIDER framework, a tool for planning and reporting qualitative evidence synthesis studies:

- S (sample) = Chronic (more than 6 months by onset) SCI patients discharged from the Spinal Unit for at least 18 months; professionals specializing in the rehabilitation and assistance of patients with SCI (physiotherapists/nurses with specialization in autonomous dysfunction management/occupational therapists/technical coordinators of rehabilitation area);

- PI (phenomenon of interest) = Continuity of territorial/home care in SCI patients;

- D (design) = Monocentric qualitative observational study;

- E (evaluation) = Facilitators and obstacles to territorial care;

- R (research type) = Focus Group Discussion.

The theoretical reference profile for the study was chronic SCI patients with a long-term disease history, in a territorial setting to access or visit diagnostic services/autonomous dysfunction re-evaluation and training/rehabilitation. Regarding professionals, we aimed to include well-trained experts with a long service in SCI assistance/rehabilitation (at least 18 months of employment at the Piacenza ASL Service and a minimum of three years of total work experience.)

A convenience sampling strategy, based on inclusion criteria, was conducted: professionals were initially contacted for participation through company e-mail by study P.I. (G.C. and E.R.), and then a short explanatory meeting was scheduled for those who wanted to participate in the survey. Patients were instead contacted from the database of the Spinal Unit; moreover, local association of para/tetraplegic patients (Associazione Paratetraplegici Piacenza) helped to promote participation in the study. A short explanatory meeting was scheduled for those who agreed to participate. According to Braun and Clarke’s approach [12], the number of participants was set at 5/8 for each Focus Group (FG).

Four FGs were conducted: two with healthcare professionals, on 9 July 2024 and on 29 July 2024, and two with the patients on 24 July 2024 and on 10 September 2024. The first group of healthcare professionals involved 4 subjects and the second involved 6 subjects, while the first group of patients involved 6 subjects and the second involved 7 subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before starting the meetings. Each Focus Group lasted about 90–120 min and was moderated by a research team member with high-level training in qualitative research (University Master’s Degree) using a predefined thematic guide (Table 1).

Table 1.

Thematic guide for both professional and patient FGs; SCI: spinal cord injury.

A thematic guide is a central tool for ensuring consistency, depth, and comparability in FGs, facilitating the systematic exploration of key issues [13,14]. It allows the moderator to keep the discussion focused while still enabling the emergence of spontaneous themes. In our study, after topic presentation, an initial ice-breaking was performed (recognizing picture of patients/health professional). Then, a progressive deepening strategy was applied to guide FG participants to the central questions (key questions): starting by association of images/words, and giving their own experiences, each group was requested to draw the concept of territorial continuity and its evolution over time. The last passage was the most important, aimed at identifying barriers and facilitators, which represented the central core of our investigation: with two key questions, participants had the possibility to refer to all possible problems in the territorial care pathway of SCI patients, both from the perspective of a user and of a health system professional.

As for FG moderation, a researcher with experience in qualitative research, employing a non-judgmental approach, was responsible for guiding subjects through questions, with the aim to ensure that all areas of investigation were addressed. The moderator was also responsible for ensuring the same involvement of all participants, with no differences in terms of time spent on each intervention. In order to reach data saturation, the moderator summarized for each area what emerged until no other contributions were added.

During FGs, an observer was responsible for gathering information on non-verbal communication. Participants were seated around a table, and firstly an ice-breaking was proposed (recognizing SCI patient photographs for healthcare professionals/photographs of healthcare professionals for SCI patients). All FGs were audio-recorded, to allow for subsequent in-depth analysis. Data saturation was achieved by triangulating redundant themes, non-verbal issues and observer/conductor adjunctive notes.

Data were analyzed, starting from the audio recordings of FGs that were manually transcribed by a research team member and checked by a second one in order to ensure consistence of transcript and avoid syntax errors. In this phase, the moderator added all his notes to the text, and a member checking with participants of all FGs was executed, in order to verify correspondence between the transcript and referred concepts. Then, a theoretical thematic approach to coding was performed according to Braun and Clarke’s [15,16] theory:

- -

- The first step regarded open coding: two research team members independently identified codes, starting with the entire transcript, through an inductive process. A code was intended as a part of the text which described the thoughts and beliefs of participants, not necessarily linked to a single sentence. After this first screening, a third researcher examined the general degree of agreement and all cases of discrepancy (e.g., diverging code assignments or differences in code boundaries). Disagreements were discussed collectively to reach consensus.

- -

- In the second phase, a reflexive thematic analysis was carried out: based on the initial codes, two researchers collaboratively generated preliminary themes and explored the presence of possible sub-themes through deeper interpretive engagement with the data.

- -

- The final stage involved theoretical coding, in order to reach higher levels of abstraction by identifying relationships between themes, and integrating them into broader conceptual categories. This final interpretative step supported the development of a theoretical framework around the concept of territorial continuity.

The final findings were presented to participants though an in-person dedicated meeting, in order to verify and review the accuracy of the data.

3. Results

A total of 23 participants were included in FG during the study; particularly, 13 patients participated to FG. As for their general characteristics, there was an even distribution by gender (six women/seven men), while age showed a very wide range (from 18 to 76 years, with a mean value of 51.25 years). With regard to the location of the spinal cord lesion, most of the included patients had a dorsal lesion (six), while cervical (two) and lumbar (three) lesions were less represented. According to AIS grading [17], the majority of the sample (six patients) had an AIS A lesion (descriptive of a complete lesion without sub-lesional preservation), four patients had AIC C classification (motor preservation below the lesion level with most muscles preserved with strength less or equal to 3) and only one patient had AIS D grade (motor preservation below the lesion level with most muscles preserved with strength greater than or equal to 3). The remaining two patients had two incomplete syndromes (Brown-Sequard and cauda equina syndrome). As for functional abilities, most patients (12 out of 13) were independent in activities of daily life with aids or devices (wheelchairs or orthoses), while 1 patient had a low degree of dependence on a caregiver. Finally, all patients were involved in social/recreational or sport activities at the time of the study, but only six of them had a regular job: four were employed, one was a bar owner and one was the chief of an ONLUS association.

Regarding professionals, 10 took part in the study: 6 physiotherapists (3 of whom worked exclusively in home settings, and 1 with a specialization in robotics), 2 occupational therapists, 1 nurse, and 1 technical coordinator of the rehabilitation area.

No drop-outs were registered for both groups.

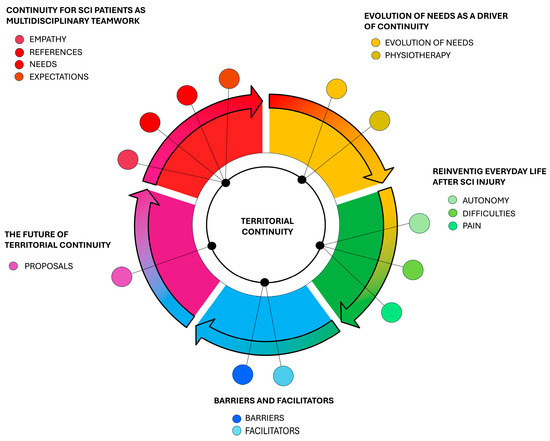

The final qualitative theory, shown in Figure 1, offers a comprehensive view of territorial continuity from patients’ and healthcare professionals’ perspectives. The analysis of the excerpts led us to identify 435 verbatim; these were grouped into 21 initial themes, of which 18 were shared between both patients and healthcare professionals, highlighting a significant convergence in their perceptions. Through this analysis we then identified five emerging themes.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of emerging themes.

The first emerging theme was named “Continuity for SCI patients as multidisciplinary teamwork”: this category included the initial themes “empathy”, “references”, “needs”, “expectations” (only patients). Multidisciplinary teamwork, including peer support, is described as a fundamental component of the continuity of care for people with spinal cord injury. Patients find great comfort and inspiration from a comparison with other people who experience a similar situation and the need for a stable and reliable point of reference is fundamental along the treatment path. FG1-P1 (patient) “physiotherapist who helped me so much, then also the figures such as nurse, Oss because they stand by you on the way, because a laugh, a smile helps you”.

The second theme was “Evolution of needs as a driver of continuity”: patients’ needs evolve as a real driving force of continuity care, stimulating professional updating by healthcare professionals. Long-term management of this condition is essential to learn and face the new challenges of daily life; it manifests as a gradual process of empowerment of the patient with a spinal cord injury and their family and caregivers, involving clinical and social dimensions. In this context, we emphasize the emerging themes of “evolution of needs” and “physiotherapy”. FG1-P2 (patient) “basically, the needs you have at the beginning are completely different, because even I just finished the course back in the day, I thought I had recovered and that I was OK for the rest of my life, but as the years go by you realize that our body ages and changes, a series of problems come up which can be sores, shoulders, the bladder that stops working and so you have a series of needs that you don’t know how to deal with”. FG 3-P5 (professional) “Territorial continuity means many things, including the possibility, after a period of intensity of care, the possibility of extending care and assistance even with lower intensity but spread over time. The fact of being able to maintain a certain level of care, precisely, with respect to all needs”.

The third main theme was “Reinventing everyday life after spinal cord injury”. Hospital discharge represents a situation of disorientation for people with SCI. Their new everyday life is often marked by challenges due to both physical obstacles and significant emotional strain. The lack of specific training for healthcare professionals on crucial issues, such as neurogenic bowel and bladder dysfunction management, further compromises the quality of care, especially with respect to emergency management. Dealing with these conditions raised the initial themes of “difficulties”, “autonomy” and “pain”. FG4-P7 (patient): “it is no longer your world, because you are different”.

The central core of our study was resumed by the emerging theme “Barriers and facilitators”, with a critical reflection on the challenging care pathway faced by individuals with SCI. Among these barriers, architectural ones emerged first and foremost, linked to physical structures and the accessibility of spaces. FG1-P3 (patient) “you face these things: the structure is unsuitable, the bathroom inaccessible and sometimes even the specialists don’t know that maybe that you can’t have sensitivity to a leg or whatever”.

Buildings, such as hospitals and rehabilitation centers, are often not designed to accommodate people with mobility restrictions, making it difficult for patients to access care easily and independently. There are also political and administrative barriers, which manifest themselves in the form of complex bureaucracy or inefficiencies. Furthermore, the lack of information has a strong negative impact on the continuity of care for people with SCI. They struggle to have access to the necessary information about the available services, treatment options and rehabilitation pathways best suited to their needs. In the same way, healthcare professionals do not know how best to direct their patients after discharge, due to the absence of a structured and formalized care program upon return home. This context generates uncertainty and concern in patients who face a delicate phase of their treatment path without having a precise point of reference and concrete indications on how to manage their condition outside the hospital environment. On the other hand, potential facilitators were identified by both groups in the form of departments which could structure contact networks for patients and professionals, increasing opportunities to exchange information and interface with highly specialized services. FG2-P2 (professional) “We have in our company a unit called hospital-territory integration: let’s work on it, I think we are one of the few companies in the region, let’s exploit it”.

The last emerging theme was “The future of territorial continuity”. Proposals for the future are highlighted both from the patient’s side and from the professional’s side, trying to identify and cultivate innovative ideas that can develop over time. Several proposals concern simple and accessible communication tools, such as brochures or computerized information databases. An identifiable information service, equipped with a physical space, with well-defined access methods and trained professionals, should be developed. Both categories support the importance of using technological tools for conducting virtual meetings which could allow workers to promptly direct patients to the correct service when a problem arises. FG4-P7 (patient) “A telemedicine dedicated to SCI patients, i.e., with a physiotherapist, nurse, doctor in it. It makes it a bit easier, reduces time, reduces distances”. FG3-P6 (professional). “An information counter, focused on actual needs that arise over time, precisely related to bowel functions or bladder, that become chronic problems”.

Another low-impact and low-cost proposal is the possibility of establishing periodic meetings between chronic discharged patients and acute patients. A similar idea is the creation of training courses for healthcare professionals organized by the most experienced colleagues. FG 3-P4 (professional) “creating more of a network, training new people”.

Finally, a further development of the case manager’s role, who should have more tools and resources and be constantly integrated in the multidisciplinary home team for all figures according to the patient’s changes (i.e., in the long term, specialized physiotherapists for setting up an adapted sport activity) was proposed.

4. Discussion

The present qualitative study was conducted in accordance with the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [18]. In accordance with the research question, the present study highlighted some central concerns about the care pathway of patients with SCI, by its definition to main opportunities or challenges that health systems should face. Our aim was in alignment with the WHO’s framework on integrated patient-centered health services (IPCHSs) [19]: engaging patients, professionals, caregivers and community represents a central strategy to achieve the co-production of health, in which each one is seen as a co-protagonist in improving the approach.

Moreover, even in accordance with WHO principles, territorial care necessitates the assurance of a seamless and integrated patient-centered trajectory, characterized by an absence of fragmentation across diverse healthcare delivery tiers (e.g., inpatient facilities, community-based services, domiciliary care) and among the multidisciplinary team, thus achieving quality, resilience and efficiency. The analysis of the FGs was consistent with such premises, revealing a significant emphasis on a patient-centric model of healthcare delivery, prioritizing individual needs, preferences and therapeutic goals [8,20].

The general perspective that emerged from the FGs regarding the nature of territorial continuity is that it evolves together with disease history: our patients revealed that, while in the initial years the strongest need is rehabilitation, to improve functional abilities, time brings out the pivotal role of managing other complications: autonomous dysfunctions, internal medicine complications and social isolation. This finding seems in line with the preceding literature [21], and results in a greater involvement of all other professionals within the multidisciplinary team: doctors, nurses, occupational therapists and social assistants.

In this scenario, multidisciplinary teamwork was highlighted as central to promoting wellbeing and health, reinforcing the idea that long-term interventions should be versatile and provide for the continuous entry of new professionals, according to the patient’s needs; this approach already has supporting evidence in the literature [22,23,24].

Regarding barriers to territorial continuity, FG participants reported different types of obstacles: physical barriers due to structures, lack of specialized healthcare professionals within the community setting and a lack of communication; these concerns result in the impossibility of addressing the complex needs of individuals with SCI [22].

On the other hand, healthcare professionals and patients recognized some opportunities to improve territorial care: among these, a strong emphasis on integrating technology in everyday work emerged. Having technology for telerehabilitation and teleconsultation provides powerful tools that would allow for more requests to be taken on board and patients to be directed to the correct service, preventing the worsening of clinical situations; the finding was in agreement with recent studies [22,25], which describe the usefulness of informatics in promoting connections between people with SCI and local services, improving equity of access to care and reducing travel for people who live in more remote locations. Teleconsultation services could represent an efficient and effective management of follow-up visits and nurses’ interventions on bowel and bladder functions [26]; a further development would be integrating a teleconsultation service for all healthcare professionals (i.e., physiotherapists). The involvement of a multidisciplinary team or a specialized consulting team, also available remotely, seems to be universally approved in the literature [25].

Other suggestions emerged about implementing communication strategies among multidisciplinary team members, through regular in-person/online meetings involving both hospital professionals and territorial ones. Furthermore, including peers within the multidisciplinary team for support and mentoring was suggested; again, this data was consistent with the preceding literature [5]. It would be interesting to introduce such figures to implement the multidisciplinary team starting from the hospital phase to select the best assistance and rehabilitation care for each patient.

Implementing these solutions through new studies will be one of the main objectives of future research in order to overcome the barriers that, even in other social and health contexts, characterize the territorial pathway of patients with SCI [27,28].

The present study had some limitations characteristic of qualitative research designs. Specifically, FGD involves a restricted number of participants, which can make it difficult to generalize the results to the entire reference population. In addition, participants in our FG were mostly autonomous, with a high functional level; this could result in bias, since patients with a higher disease impact and less self-efficacy could have provided a different perspective on territorial care. Also, involving patients with a higher neurological level could have reflected different categories of needs that did not emerge in this study (i.e., total dependence on a caregiver in ADLs). Moreover, while patients lived in different territorial contexts, the professionals were all part of the same public healthcare company, which could represent another limit in the generalizability of our conclusions.

From a methodological point of view, finally, despite the effort to control variability and report consistent data, the answers could have also been influenced by individual and subjective factors (bias of social desirability), which may impact the interpretation of the collected data.

5. Conclusions

Territorial continuity of care, for patients with SCI and health professionals, represents an ongoing challenge of multi-professional integration, in which the patient rediscovers themself to maximize residual resources, and deals with a “new” normality. This study highlighted that the concept is not static, but evolves with time and the patient’s needs: if at first the emphasis is on physiotherapy, desiring the highest possible functional recovery, the progressive emergence of complications (e.g., neurogenic bladder dysfunction) makes the intervention of other figures, such as the nurse, central. In addition, in the long term, the need to reconnect with the social world by making new experiences, with the involvement of psychologists, occupational therapists, sports therapists and social workers, emerges.

Our study also reported obstacles and strengths of the care pathway: barriers, in this sense, deserve the utmost attention from researchers, clinicians and decision-makers, as they can lead to delays in recovery, frustration on the part of the patient and increased care costs due to complications. A challenge for the future, at all levels of the healthcare system, will be to implement a change in mentality, from structures (breaking down barriers) to inter-professional communication. Technology, finally, deserves a deeper consideration as a tool for overcoming distances and achieving proximity healthcare, in the direction of an increasingly patient-centered approach to SCI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.M., G.C., E.R. and F.A.; methodology, G.C. and E.R.; software, A.D.M.; validation, A.C., V.C., G.L. and A.D.M.; formal analysis, A.D.M., G.C. and F.A.; investigation, F.A., E.R., G.C. and A.D.M.; resources, V.C., A.C. and G.L.; data curation, A.D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C., A.D.M. and E.R.; writing—review and editing, A.D.M., G.C., E.R. and F.A.; visualization, G.L., V.C. and A.C.; supervision, V.C. and A.C.; project administration, G.C., A.D.M. and E.R.; funding acquisition, G.L., V.C. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by AVEN Ethics Committee (protocol code no. 2024/0053582; approval date: 16 May 2024) and received corporate approval from Azienda Usl of Piacenza (protocol code no. 2024/0000243; approval date: 6 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and professionals who took part to the study, and Piacenza Paratetraplegici Association for supporting recruitment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCI | Spinal Cord Injury |

| FDG | Focus Group Discussion |

| FGs | Focus Groups |

| P | Participant |

References

- Jeyathevan, G.; Craven, B.C.; Cameron, J.I.; Jaglal, S.B. Facilitators and Barriers to Supporting Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury in the Community: Experiences of Family Caregivers and Care Recipients. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 1844–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Spinal Cord Injury. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/spinal-cord-injury (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Kim, Y.-H.; Ha, K.-Y.; Kim, S.-I. Spinal Cord Injury and Related Clinical Trials. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2017, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Diemen, T.; van Nes, I.J.W.; van Laake-Geelen, C.C.M.; Spijkerman, D.; Geertzen, J.H.B.; Post, M.W.M. Learning Self-Care Skills after Spinal Cord Injury: A Qualitative Study. BMC Psychol. 2021, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maribo, T.; Jensen, C.M.; Madsen, L.S.; Handberg, C. Experiences with and Perspectives on Goal Setting in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Spinal Cord 2020, 58, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gedde, M.H.; Lilleberg, H.S.; Aßmus, J.; Gilhus, N.E.; Rekand, T. Traumatic vs Non-Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury: A Comparison of Primary Rehabilitation Outcomes and Complications during Hospitalization. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2019, 42, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson-Gill, C.; Mingo, T. Primary Care in the Spinal Cord Injury Population: Things to Consider in the Ongoing Discussion. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2023, 11, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, M.; Sharifi, A.; Vaccaro, A.; Rahimi-Movaghar, V. Home-Based Rehabilitation Programs: Promising Field to Maximize Function of Patients with Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2019, 14, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, J.; Burns, S.; Groah, S.; Howcroft, J. A Primary Care Provider’s Guide to Preventive Health After Spinal Cord Injury. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2020, 26, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P. Medical Education Singapore Med Focus Group Discussion: A Tool for Health and Medical Research. Singap. Med. J. 2008, 49, 256. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, P.; Laffi, P.; Rovesti, S.; Artioli, G.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Magnani, V. Motivational Factors for Choosing the Degree Course in Nursing: A Focus Group Study with Nursing Students. Acta Biomed. Health Prof. 2016, 87, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; Sage: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–378. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, M.; Greenwood, J. A guide to the use of focus groups in health care research: Part 1. Contemp. Nurse 2000, 9, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalmeijee, R.E.; Mcnaughton, N.; Van Mook, W.N.K.A. Using focus groups in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 91. Med. Teach. 2014, 36, 923–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2020, 18, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.; Biering-Sørensen, F.; Burns, S.P.; Graves, D.E.; Guest, J.; Jones, L.; Read, M.S.; Rodriguez, G.M.; Schuld, C.; Tansey, K.E.; et al. International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury: Revised 2019. Top. Spinal Cord Inj. Rehabil. 2021, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Assembly. Framework on Integrated, People-Centred Health Services: Report by the Secretariat; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; WHA69.

- Unger, J.; Singh, H.; Mansfield, A.; Hitzig, S.L.; Lenton, E.; Musselman, K.E. The Experiences of Physical Rehabilitation in Individuals with Spinal Cord Injuries: A Qualitative Thematic Synthesis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1367–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsett, P.; Geraghty, T. Health-related outcomes of people with spinal cord injury—A 10 year longitudinal study. Spinal Cord 2008, 46, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.J.; Amsters, D.I.; Pershouse, K.J. The Need for a Multidisciplinary Outreach Service for People with Spinal Cord Injury Living in the Community. Clin. Rehabil. 2001, 15, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, R.; Qu, M.; Yuan, Y.; Lin, M.; Liu, T.; Huang, W.; Gao, J.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X. Clinical Benefit of Rehabilitation Training in Spinal Cord Injury. Spine 2021, 46, E398–E410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshanrad, N.; Vosoughi, F.; Yekaninejad, M.S.; Moshayedi, P.; Saberi, H. Erratum: Functional Impact of Multidisciplinary Outpatient Program on Patients with Chronic Complete Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord 2015, 53, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.; Atchison, K.; Noonan, V.K.; McKenzie, N.; Cadel, L.; Ganshorn, H.; Rivera, J.M.B.; Yousefi, C.; Guilcher, S.J.T. Models of Care Delivery from Rehabilitation to Community for Spinal Cord Injury: A Scoping Review. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touchett, H.; Apodaca, C.; Siddiqui, S.; Huang, D.; Helmer, D.A.; Lindsay, J.A.; Ramaswamy, P.; Marchant-Miros, K.; Skelton, F. Current Approaches in Telehealth and Telerehabilitation for Spinal Cord Injury (TeleSCI). Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2022, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollé-Espluga, L.; Vargas, I.; Mogollón-Pérez, A.; Soares-de-Jesus, R.F.; Eguiguren, P.; Cisneros, A.I.; Muruaga, M.C.; Huerta, A.; Bertolotto, F.; Vázquez, M.L. Care continuity across levels of care perceived by patients with chronic conditions in six Latin-American countries. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinel-Flores, V.; Vargas, I.; Eguiguren, P.; Mogollón-Pérez, A.S.; Ferreira de Medeiros Mendes, M.; López-Vázquez, J.; Bertolotto, F.; Vázquez, M.L. Assessing the impact of clinical coordination interventions on the continuity of care for patients with chronic conditions: Participatory action research in five Latin American countries. Health Policy Plan. 2022, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).