First-Serve Advantage and Emerging Tactical Limitations in Elite U-14 Boys’ Tennis: A Les Petits as Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

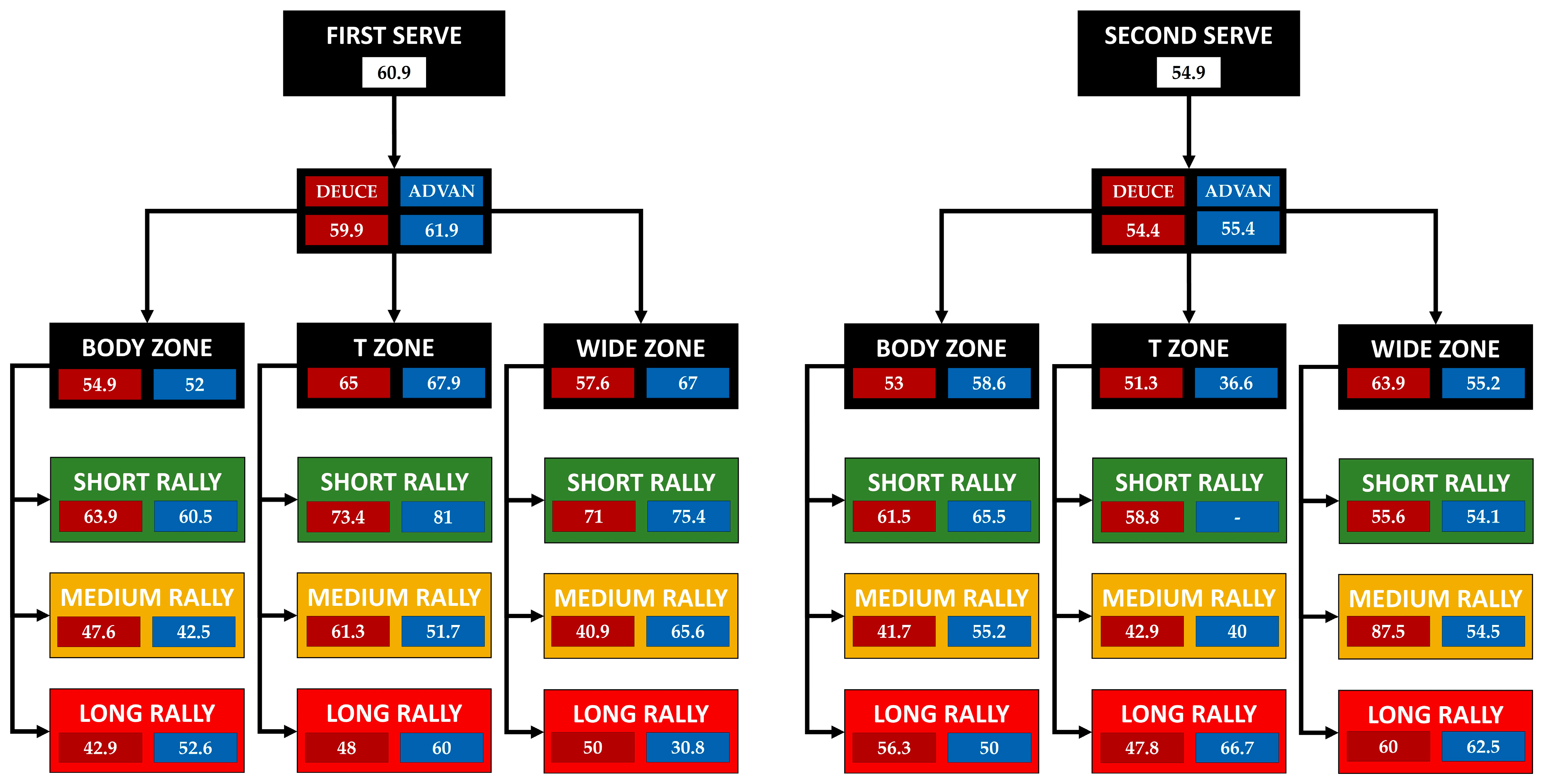

3.2. Serve Patterns of Play

4. Discussion

4.1. First Serve Analysis

4.2. Second Serve Analysis

4.3. Game Patterns

4.4. Practical Applications

4.5. Limitations of the Research and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brouwers, J.; De Bosscher, V.; Sotiriadou, P. An examination of the importance of performances in youth and junior competition as an indicator of later success in tennis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Campos, M.; Martínez-Gallego, R. Analysis of serve and first shot sequences in U-12 and U-14 tennis players. ITF Coach. Sport Sci. Rev. 2024, 32, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, A.; Bradshaw, R.; Young, W.; O’Brien, B.; Zois, J. Success in national level junior tennis: Tactical perspectives. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2017, 12, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Luque, G.; Cabello-Manrique, D.; Hernández-García, R.; Garatachea, N. An analysis of competition in young tennis players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2011, 11, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janák, O.; Zháněl, J. Analysis of the game characteristics of the final juniors (female) match U14 at World Junior Tennis Finals in 2017 (case study). Stud. Sport 2019, 13, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, L.; Iglesias, D.; Moreno, A.; Moreno, M.P.; Del Villar, F. Tactical Knowledge in Tennis: A Comparison of Two Groups with Different Levels of Expertise. Percept. Mot. Skills 2012, 115, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzios, C.; Athanailidis, I.; Arvanitidou, V.; Mourtziou, M.-A. Variation in Psychological Profiles of Young Tennis Players, Boys, and Girls Aged 11–14. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2024, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Filipcic, A. Determining the tactical and technical level of competitive tennis players using a competency model: A systematic review. Front. Sport. Act. Living 2024, 6, 1406846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, M.T.; Blanco-Villaseñor, A.; Losada, J.L.; Portell, M. Guidelines for designing and conducting a study that applies observational methodology. Anu. Psicol. 2018, 48, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, M.T.; Blanco-Villaseñor, A.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; Losada-López, J.L. Observational designs: Their suitability and application in sports psychology. Cuad. Psicol. Deport. 2011, 11, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Lage, I.; Paramés-González, A.; Torres-Santos, D.; Argibay-González, J.C.; Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, X.; GutiérrezSantiago, A. Match analysis and probability of winning a point in elite men’s singles tennis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Santiago, A.; Cidre-Fuentes, P.; Orío-García, E.; Silva-Pinto, A.J.; Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, X.; Prieto-Lage, I. Women’s Singles Tennis Match Analysis and Probability of Winning a Point. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, A.; Camerino, O.; Iglesias, X.; Anguera, M.T.; Castañer, M. LINCE PLUS: Research Software for Behavior Video Analysis. Apunt. Educ. Física Esports 2019, 3, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Villaseñor, A.; Anguera, M.T. Evaluación de la calidad en el registro del comportamiento: Aplicación a deportes de equipo. In Métodos Numéricos en Ciencias Sociales; Oñate, E., García-Sicilia, F., Ramallo, L., Eds.; Centro Internacional de Métodos Numéricos en Ingeniería: Barcelona, Spain, 2000; pp. 30–48. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement of partial credit. Psychol. Bull. 1968, 70, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecheri, S.; Rioult, F.; Mantel, B.; Kauffmann, F.; Benguigui, N. The serve impact in tennis: First large-scale study of big Hawk-Eye data. Stat. Anal. Data Min. 2016, 9, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M.S. Discovering hidden time patterns in behavior: T-patterns and their detection. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2000, 32, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M.S. T-Pattern Detection and Analysis (TPA) With THEME TM: A Mixed Methods Approach. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 02663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, E.; Leroy, D.; Thouvarecq, R.; Stein, J.F. A notational analysis of elite tennis serve and serve-return strategies on slow surface. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, A.; Stone, J.A.; Choppin, S.; Kelley, J. Investigating the most important aspect of elite grass court tennis: Short points. Int. J. Sport. Sci. Coach. 2021, 16, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizan, H.; Whipp, P.; Reid, M. Gender Differences in the Spatial Distributions of the Tennis Serve. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2015, 10, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldziński, T.; Waldzińska, E.; Durzyńska, A.; Niespodziński, B.; Mieszkowski, J.; Kochanowicz, A. One-year developmental changes in motor coordination and tennis skills in 10–12-year-old male and female tennis players. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2024, 16, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Gallego, R.; Guzmán Luján, J.F.; James, N.; Pers, J.; Ramón-Llin, J.; Vuckovic, G. Movement characteristics of elite tennis players on hard courts with respect to the direction of ground strokes. J. Sport. Sci. Med. 2013, 12, 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Vacek, J.; Vagner, M.; Cleather, D.J.; Stastny, P. A Systematic Review of Spatial Differences of the Ball Impact within the Serve Type at Professional and Junior Tennis Players. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

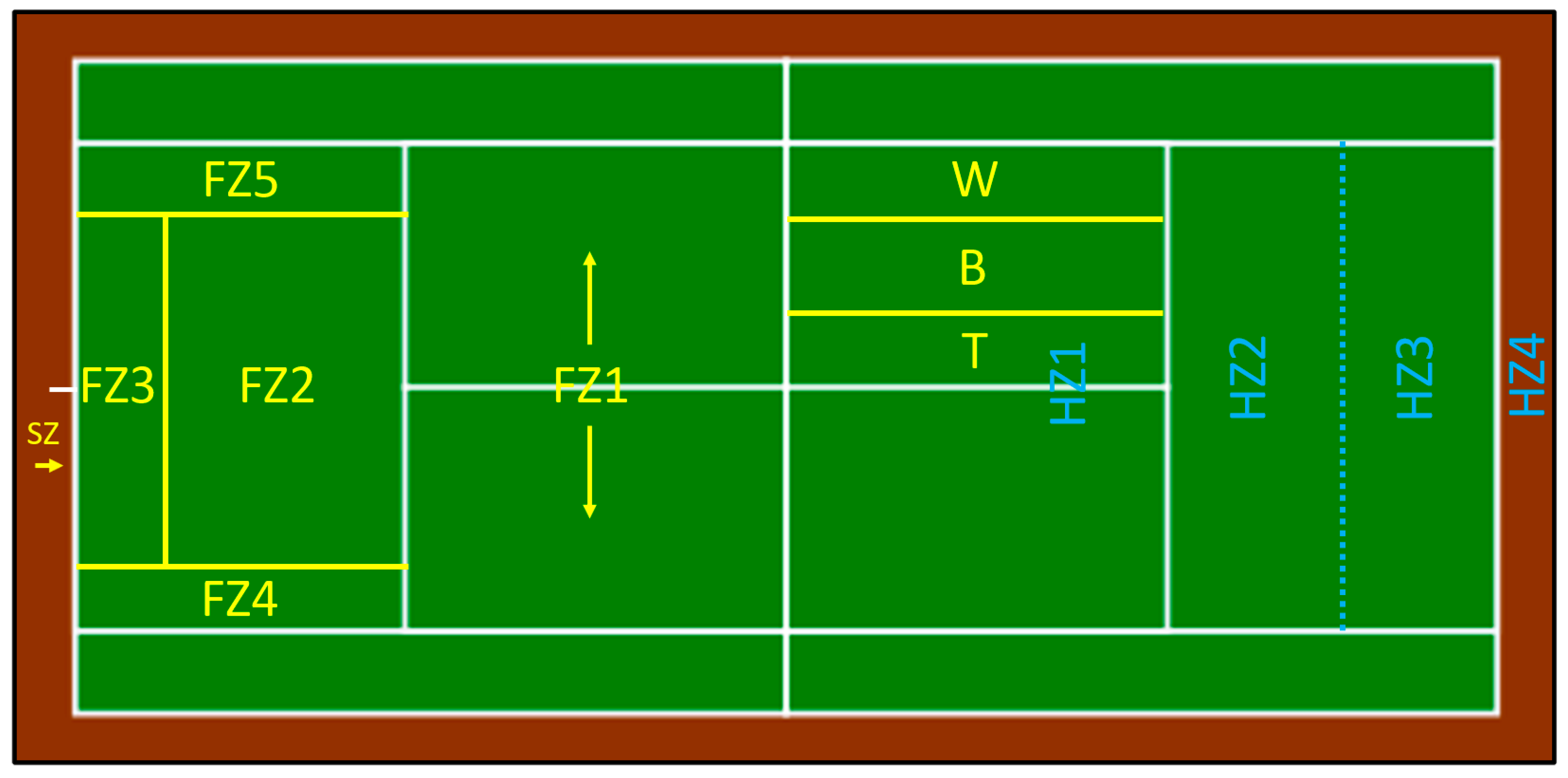

| CRITERIA | CODE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

| SERVICE BOX | DE | The player serves from the deuce side |

| AD | The player serves from the advantage side. | |

| SERVICE | FS | The point is played with the first serve |

| SS | The point is played with the second serve. | |

| DF | The server commits a double fault. | |

| TARGET SERVICE BOX | T | Serve directed to the T zone. |

| B | Serve directed to the middle of the service box (body zone). | |

| W | Serve directed to the wide third of the service box. | |

| RALLY LENGTH | SH | Short rally (0–4 shots), including the serve. |

| MD | Medium rally (5–8 shots), including the serve. | |

| LN | Long rally (9+ shots), including the serve. | |

| HITTING ZONE | HZ1 | One foot inside the service box. |

| HZ2 | One foot between the first half of the service line and the baseline. | |

| HZ3 | One foot between the second half of the service line and the baseline. | |

| HZ4 | Both feet outside the baseline. | |

| SZ | Ace or double fault (serve zone) | |

| FINAL STROKE | FH | Forehand shot. |

| BH | Backhand shot. | |

| OTH | Other types of shots (drop shot, smash, volley, etc.). | |

| ACE | Ace (direct serve). | |

| FINISH ZONE | FZ1-FZ5 | Zone of the court where the ball is directed (only for winners). |

| NET | The final shot goes into the net. | |

| SLO | The final shot goes out through the sideline. | |

| BSO | The final shot goes out through the baseline. | |

| WINNER | SW | Server wins the point. |

| RW | Receiver wins the point. | |

| POINT ENDING | SWW | The server wins with a winning shot. |

| SWUE | The server wins due to an unforced error by the opponent. | |

| SWFE | The server wins due to a forced error by the opponent. | |

| RWW | The receiver wins with a winning shot. | |

| RWUE | The receiver wins due to an unforced error by the opponent. | |

| RWFE | The receiver wins due to a forced error by the opponent. |

| Criteria | Intra-Kappa Obs1–Obs1 | Intra-Kappa Obs2–Obs2 | Inter-Kappa Obs1–Obs2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Start & end point | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Service box | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Service | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Target Service box | 0.92 | 0.9 | 0.87 |

| Rally length | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Hitting zone | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Final Stroke | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 |

| Finish zone | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

| Winner | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 |

| Point ending | 0.89 | 0.9 | 0.87 |

| Average | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.93 |

| Criterion | Code | n | % | χ2 Goodness-of-Fit | Criterion | Code | n | % | χ2 Goodness-of-Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERVICE BOX | AD | 459 | 47.3 | χ2 = 2.893 | FINAL STROKE | ACE | 50 | 5.1 | χ2 = 280.300 |

| DE | 512 | 52.7 | p = 0.089 | BH | 366 | 37.7 | p < 0.000 | ||

| SERVICE | DF | 45 | 4.6 | χ2 = 472.501 | FH | 359 | 37.0 | ||

| FS | 598 | 61.6 | p < 0.000 | OTH | 196 | 20.2 | |||

| SS | 328 | 33.8 | FINISH ZONE | BSO | 208 | 21.4 | χ2 = 269.082 | ||

| TARGET SERVICE BOX | B | 309 | 31.8 | χ2 = 217.610 | SLO | 140 | 14.4 | p < 0.000 | |

| NA | 45 | 4.6 | p < 0.000 | NET | 196 | 20.2 | |||

| T | 290 | 29.9 | FZ1 | 179 | 18.4 | ||||

| W | 327 | 33.7 | FZ2 | 59 | 6.1 | ||||

| RALLY LENGHT | LN | 165 | 17.0 | χ2 = 174.812 | FZ3 | 32 | 3.3 | ||

| MD | 306 | 31.5 | p < 0.000 | FZ4 | 65 | 6.7 | |||

| SH | 500 | 51.5 | FZ5 | 92 | 9.5 | ||||

| HITTING ZONE | HZ1 | 90 | 9.3 | χ2 = 640.601 | WINNER | RW | 427 | 44.0 | χ2 = 14.098 |

| HZ2 | 56 | 5.8 | p < 0.000 | SW | 544 | 56.0 | p < 0.000 | ||

| HZ3 | 236 | 24.3 | POINT ENDING | RWFE | 60 | 6.2 | χ2 = 334.942 | ||

| HZ4 | 485 | 49.9 | RWUE | 276 | 28.4 | p < 0.000 | |||

| SZ | 104 | 10.7 | RWW | 91 | 9.4 | ||||

| SWFE | 70 | 7.2 | |||||||

| SWUE | 292 | 30.1 | |||||||

| SWW | 182 | 18.7 |

| First Serve (Deuce) | First Serve (Advantage) | DE-AD Comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Code | N | % | χ2 Goodness-of-Fit | N | % | χ2 Goodness-of-Fit | χ2 of Independence |

| TARGET SERVICE BOX | B | 71 | 23.0 | χ2 = 14.932 p < 0.001 | 102 | 35.3 | χ2 = 3.744 p = 0.154 | χ2 = 13.111 p < 0.000 V = 0.148 |

| T | 120 | 38.8 | 81 | 28.0 | ||||

| W | 118 | 38.2 | 106 | 36.7 | ||||

| RALLY LENGHT | LN | 51 | 16.5 | χ2 = 60.524 p < 0.000 | 42 | 14.5 | χ2 = 56.478 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 1.161 p = 0.559 |

| MD | 96 | 31.1 | 101 | 34.9 | ||||

| SH | 162 | 52.4 | 146 | 50.5 | ||||

| HITTING ZONE | HZ1 | 27 | 8.7 | χ2 = 222.117 p < 0.000 | 25 | 8.7 | χ2 = 230.118 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 5.919 p = 0.205 |

| HZ2 | 15 | 4.9 | 17 | 5.9 | ||||

| HZ3 | 70 | 22.7 | 77 | 26.6 | ||||

| HZ4 | 160 | 51.8 | 151 | 52.2 | ||||

| SZ | 37 | 12.0 | 19 | 6.6 | ||||

| FINAL STROKE | ACE | 31 | 10.0 | χ2 = 77.472 p < 0.000 | 16 | 5.5 | χ2 = 91.526 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 5.337 p = 0.149 |

| BH | 117 | 37.9 | 103 | 35.6 | ||||

| FH | 114 | 36.9 | 118 | 40.8 | ||||

| OTH | 47 | 15.2 | 52 | 18.0 | ||||

| FINISH ZONE | BSO | 65 | 21.0 | χ2 = 126.184 p < 0.000 | 69 | 23.9 | χ2 = 94.917 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 8.029 p = 0.330 |

| SLO | 41 | 13.3 | 43 | 14.9 | ||||

| NET | 53 | 17.2 | 58 | 20.1 | ||||

| FZ1 | 82 | 26.5 | 51 | 17.6 | ||||

| FZ2 | 12 | 3.9 | 14 | 4.8 | ||||

| FZ3 | 9 | 2.9 | 12 | 4.2 | ||||

| FZ4 | 19 | 6.1 | 15 | 5.2 | ||||

| FZ5 | 28 | 9.1 | 27 | 9.3 | ||||

| WINNER | RW | 124 | 40.1 | χ2 = 12.042 p < 0.001 | 110 | 38.1 | χ2 = 16.474 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 0.268 p = 0.605 |

| SW | 185 | 59.9 | 179 | 61.9 | ||||

| POINT ENDING | RWFE | 22 | 7.1 | χ2 = 88.029 p < 0.000 | 16 | 5.5 | χ2 = 110.093 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 7.877 p = 0.163 |

| RWUE | 71 | 23.0 | 73 | 25.3 | ||||

| RWW | 31 | 10.0 | 21 | 7.3 | ||||

| SWFE | 21 | 6.8 | 28 | 9.7 | ||||

| SWUE | 88 | 28.5 | 98 | 33.9 | ||||

| SWW | 76 | 24.6 | 53 | 18.3 | ||||

| Second Serve (Deuce) | Second Serve (Advantage) | DE-AD Comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Code | N | % | χ2 Goodness-of-Fit | N | % | χ2 Goodness-of-Fit | χ2 of Independence |

| TARGET SERVICE BOX | CN | 66 | 36.7 | χ2 = 15.600 p < 0.000 | 70 | 47.3 | χ2 = 44.770 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 57.309 p < 0.000 V = 0.418 |

| T | 78 | 43.3 | 11 | 7.4 | ||||

| W | 36 | 20.0 | 67 | 45.3 | ||||

| RALLY LENGHT | LN | 49 | 27.2 | χ2 = 8.233 p < 0.016 | 23 | 15.5 | χ2 = 22.797 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 6.967 p < 0.031 V = 0.146 |

| MD | 53 | 29.4 | 56 | 37.8 | ||||

| SH | 78 | 43.3 | 69 | 46.6 | ||||

| HITTING ZONE | ZG1 | 23 | 12.8 | χ2 = 144.167 p < 0.000 | 15 | 10.1 | χ2 = 145.108 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 3.357 p < 0.500 |

| ZG2 | 11 | 6.1 | 13 | 8.8 | ||||

| ZG3 | 54 | 10.0 | 35 | 23.6 | ||||

| ZG4 | 90 | 50.0 | 84 | 56.8 | ||||

| ZGS | 2 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.7 | ||||

| FINAL STROKE | ACE | 2 | 1.1 | χ2 = 79.867 p < 0.000 | 1 | 0.7 | χ2 = 83.838 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 1.880 p < 0.598 |

| BH | 75 | 41.7 | 71 | 48.0 | ||||

| FH | 71 | 39.4 | 56 | 37.8 | ||||

| OTH | 32 | 17.8 | 20 | 13.5 | ||||

| FINISH ZONE | BSO | 35 | 19.4 | χ2 = 43.111 p < 0.000 | 39 | 26.4 | χ2 = 59.676 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 15.914 p < 0.026 V = 0.026 |

| LTO | 23 | 12.8 | 29 | 19.6 | ||||

| NET | 40 | 22.2 | 25 | 16.9 | ||||

| Z1 | 26 | 14.4 | 19 | 12.8 | ||||

| Z2 | 10 | 5.6 | 3 | 2.0 | ||||

| Z3 | 5 | 2.8 | 6 | 4.1 | ||||

| Z4 | 24 | 13.3 | 7 | 4.7 | ||||

| Z5 | 17 | 9.4 | 20 | 13.5 | ||||

| WINNER | RW | 82 | 45.6 | χ2 = 1.422 p = 0.223 | 66 | 44.6 | χ2 = 1.730 p = 0.188 | χ2 = 0.030 p < 0.862 |

| SW | 98 | 54.4 | 82 | 55.4 | ||||

| POINT ENDING | RWFE | 14 | 7.8 | χ2 = 54.200 p < 0.000 | 8 | 5.4 | χ2 = 63.865 p < 0.000 | χ2 = 7.475 p < 0.188 |

| RWUE | 43 | 23.9 | 44 | 29.7 | ||||

| RWW | 25 | 13.9 | 14 | 9.5 | ||||

| SWFE | 8 | 4.4 | 13 | 8.8 | ||||

| SWUE | 56 | 31.1 | 50 | 33.8 | ||||

| SWW | 34 | 18.9 | 19 | 12.8 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prieto-Lage, I.; Crespo, M.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, X.; Silva-Pinto, A.J.; Gutiérrez-Santiago, A. First-Serve Advantage and Emerging Tactical Limitations in Elite U-14 Boys’ Tennis: A Les Petits as Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105341

Prieto-Lage I, Crespo M, Martínez-Gallego R, Reguera-López-de-la-Osa X, Silva-Pinto AJ, Gutiérrez-Santiago A. First-Serve Advantage and Emerging Tactical Limitations in Elite U-14 Boys’ Tennis: A Les Petits as Case Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(10):5341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105341

Chicago/Turabian StylePrieto-Lage, Iván, Miguel Crespo, Rafael Martínez-Gallego, Xoana Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, Antonio José Silva-Pinto, and Alfonso Gutiérrez-Santiago. 2025. "First-Serve Advantage and Emerging Tactical Limitations in Elite U-14 Boys’ Tennis: A Les Petits as Case Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 10: 5341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105341

APA StylePrieto-Lage, I., Crespo, M., Martínez-Gallego, R., Reguera-López-de-la-Osa, X., Silva-Pinto, A. J., & Gutiérrez-Santiago, A. (2025). First-Serve Advantage and Emerging Tactical Limitations in Elite U-14 Boys’ Tennis: A Les Petits as Case Study. Applied Sciences, 15(10), 5341. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105341