A Study on Factors Affecting the Continuance Usage Intention of Social Robots with Episodic Memory: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

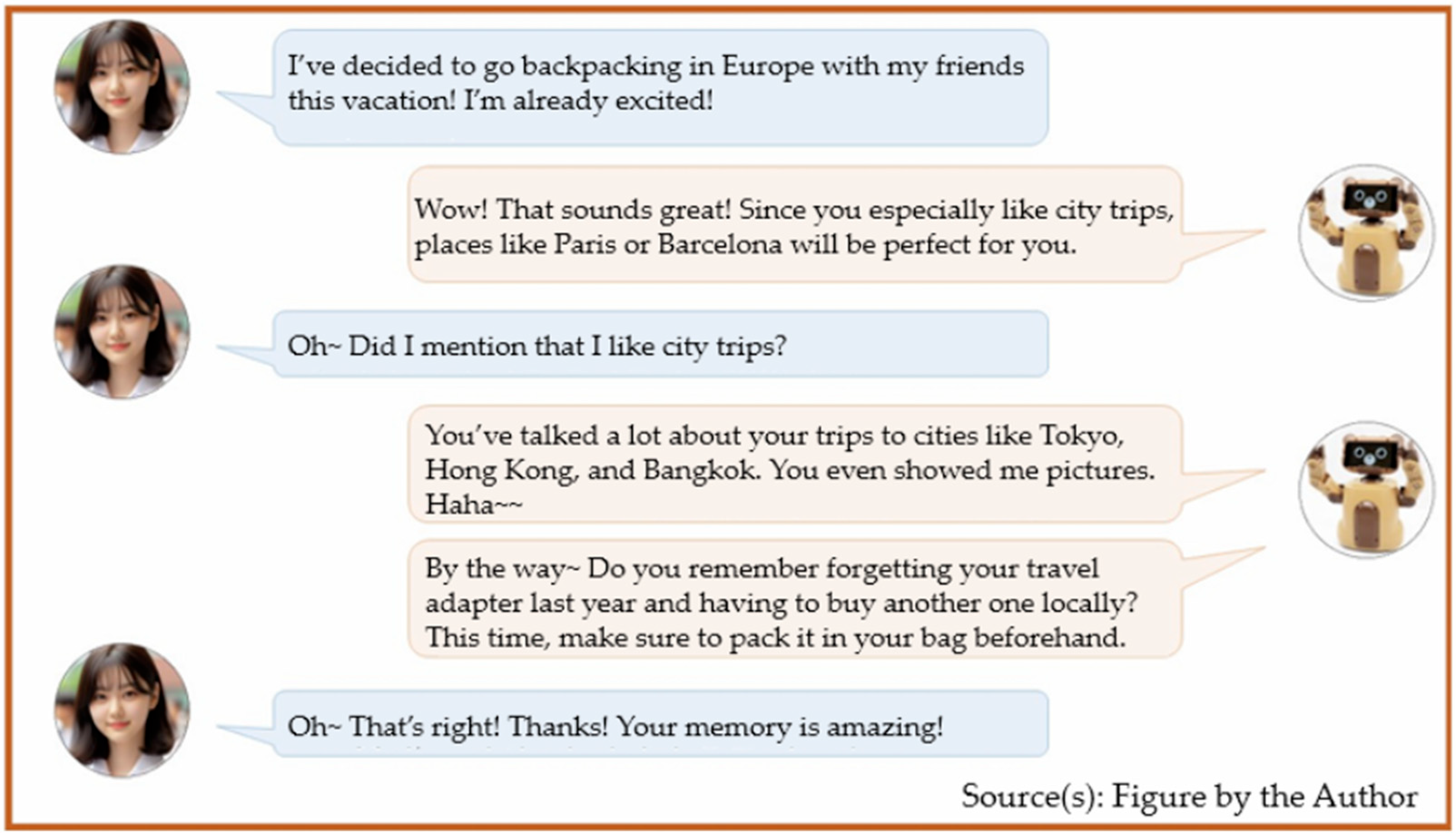

2.1. The Social Robot—MOCCA

2.2. The Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) Theoretical Framework

2.3. Stimulus (S): Social Robot (MOCCA)’s Features

2.3.1. Perceived Anthropomorphism—Intimacy (PAI)

2.3.2. Perceived Agency—Morality (PAM) and Dependency (PAD)

2.3.3. Perceived Risk—Information Privacy Risk (IPR)

2.4. Organism (O): Human–Social Robot Relationships

2.4.1. Parasocial Interaction with MOCCA (PSI)

2.4.2. Trust with MOCCA (TRS)

2.5. Response (R): Continuance Usage Intention (CUI)

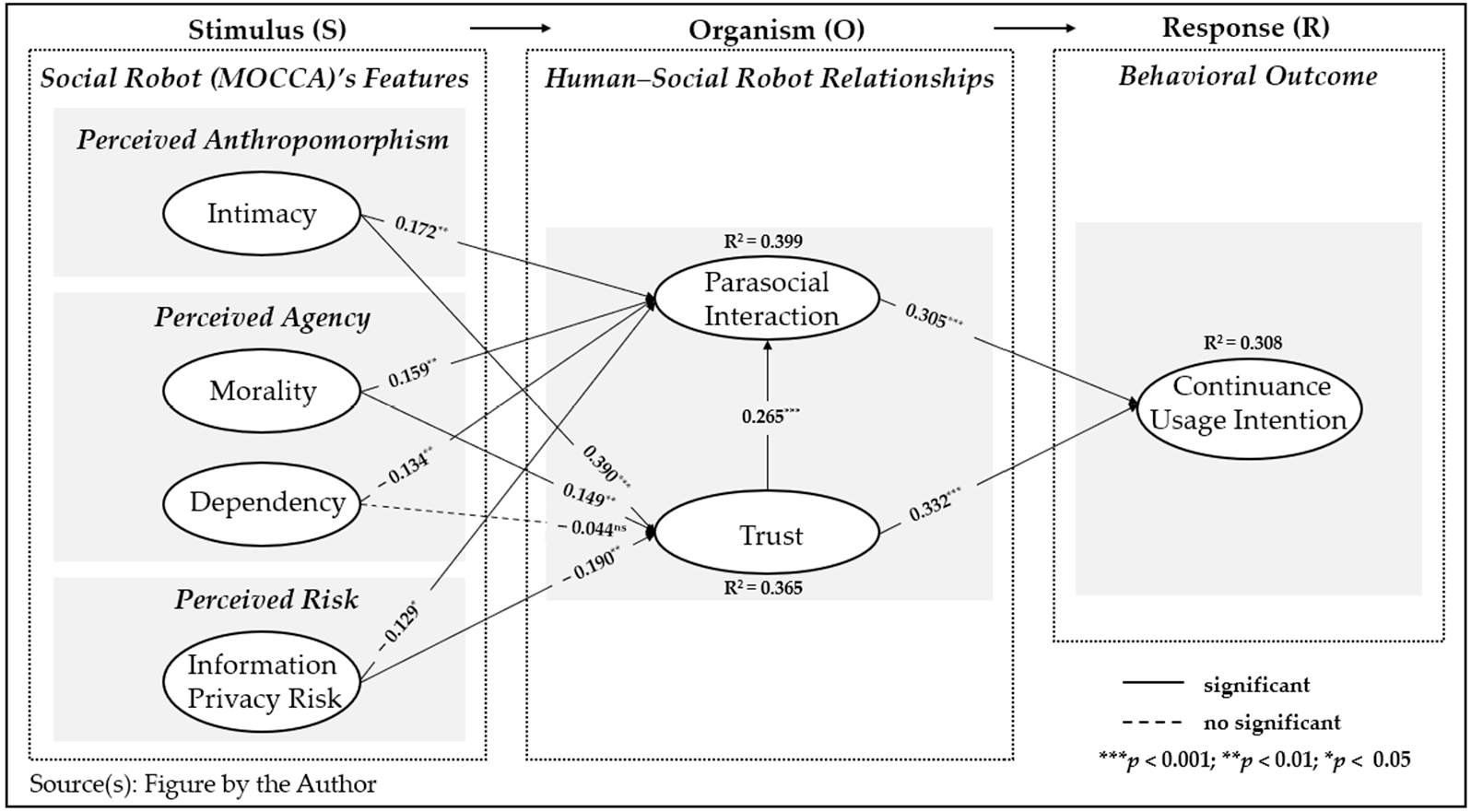

2.6. Structural Model Based on the SOR Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Data Sampling and Collection

3.3. Statistical Processing Methods for Hypothesis Testing

3.3.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

3.3.2. Assessment of Structural Model

4. Hypothesis Testing Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

7. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johanson, D.L.; Ahn, H.S.; Broadbent, E. Improving interactions with healthcare robots: A review of communication behaviors in social and healthcare contexts. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2021, 13, 1835–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.; LeTendre, G.K.; Pham-Shouse, T.; Xiong, Y. The use of social robots in classrooms: A review of field-based studies. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 33, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.S.; Kim, Y.K. The role of the human-robot interaction in consumers’ acceptance of humanoid retail service robots. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Huang, J. Think like a robot: How interactions with humanoid service robots affect consumers’ decision strategies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D. Usage intention of social robots for domestic purpose: From security, privacy, and legal perspectives. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Xu, J.; Hussain, S.; Wang, H.; Gao, N.; Zhang, L. Trends and prediction in daily new cases and deaths of COVID-19 in the United States: An internet search-interest based model. Explor. Res. Hypothesis Med. 2020, 5, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Luximon, A.; Luximon, Y. The effect of facial features on facial anthropomorphic trustworthiness in social robots. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 94, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Yoo, S.M.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, U.H.; Kim, J.H. Human robot social interaction framework based on emotional episodic memory. In Proceedings of the Robot Intelligence Technology and Applications: 6th International Conference, Putrajaya, Malaysia, 16–18 December 2018; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 6, pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Abba Ari, A.A.; Ngangmo, O.K.; Titouna, C.; Thiare, O.; Mohamadou, A.; Gueroui, A.M. Enabling privacy and security in Cloud of Things: Architecture, applications, security & privacy challenges. Appl. Comput. Inform. 2024, 20, 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Xing, X.; Duan, Y.; Cohen, J.; Mou, J. Will artificial intelligence replace human customer service? The impact of communication quality and privacy risks on adoption intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruma, S.O.; Ayele, Y.Z.; Sechi, F.; Rødsethol, H. Security aspects of social robots in public spaces: A systematic mapping study. Sensors 2023, 23, 8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laban, G.; Cross, E.S. Sharing our Emotions with Robots: Why do we do it and how does it make us feel? IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2024, 3470984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Kang, H.; Jun, S. Verbal anthropomorphism design of social robots: Investigating users’ privacy perception. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 142, 107640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, A.H.; Chou, S.Y. Exploring robot service quality priorities for different levels of intimacy with service. Serv. Bus. 2023, 17, 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premathilake, G.W.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Liu, Y.; Han, S. Understanding the effect of anthropomorphic features of humanoid social robots on user satisfaction: A stimulus-organism-response approach. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025, 125, 768–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.T. On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 114, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaigbena, A.; Lottu, O.A.; Ugwuanyi, E.D.; Jacks, B.S.; Sodiya, E.O.; Daraojimba, O.D. AI and human-robot interaction: A review of recent advances and challenges. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 18, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. A perceived moral agency scale: Development and validation of a metric for humans and social machines. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. The Ethics of Information; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dignum, V.; Dignum, F.; Vázquez-Salceda, J.; Clodic, A.; Gentile, M.; Mascarenhas, S.; Augello, A. Design for values for social robot architectures. In Envisioning Robots in Society–Power, Politics, and Public Space; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 311, pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tavani, H.T. Can social robots qualify for moral consideration? Reframing the question about robot rights. Information 2018, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.B.; Williams, T. A theory of social agency for human-robot interaction. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 687726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Shin, W.; Cho, H. A study on preschool children’s perceptions of a robot’s theory of mind. J. Korea Robot. Soc. 2020, 15, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumalloh, R.A.; Halabi, O.; Nilashi, M. The relationship between technology trust and behavioral intention to use Metaverse in baby monitoring systems’ design: Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) theory. Entertain. Comput. 2025, 52, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei-Zadeh, A.; Nikbin, D.; Wong, S.L.; Hanifah, H. Investigating factors influencing AI customer service adoption: An integrated model of stimulus–organism–response (SOR) and task-technology fit (TTF) theory. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Breazeal, C. Toward sociable robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2003, 42, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, M.M.; Allouch, S.B. Exploring influencing variables for the acceptance of social robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, T.; Nourbakhsh, I.; Dautenhahn, K. A survey of socially interactive robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2003, 42, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formosa, P. Robot autonomy vs. human autonomy: Social robots, artificial intelligence (AI), and the nature of autonomy. Minds Mach. 2021, 31, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Park, C.H.; Jang, S.; Cho, H.K. Design of effective robotic gaze-based social cueing for users in task-oriented situations: How to overcome in-attentional blindness? Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, N.T.; Hancer, M. Human-robot collaboration in service recovery: Examining apology styles, comfort emotions, and customer retention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 126, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chang, Y.; Yang, T.; Yu, Z. Consumer acceptance of social robots in domestic settings: A human-robot interaction perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaguer Gómez, G. Should we Trust Social Robots? Trust without Trustworthiness in Human-Robot Interaction. Philos. Technol. 2025, 38, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.H.; Tang, K.Y. Who captures whom–Pokémon or tourists? A perspective of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 61, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhu, K.; Zhou, P.; Liang, C. How does anthropomorphism improve human-AI interaction satisfaction: A dual-path model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whang, C.; Im, H. “I Like Your Suggestion!” the role of humanlikeness and parasocial relationship on the website versus voice shopper’s perception of recommendations. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroessner, S.J.; Benitez, J. The social perception of humanoid and non-humanoid robots: Effects of gendered and machinelike features. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2019, 11, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blut, M.; Wang, C.; Wünderlich, N.V.; Brock, C. Understanding anthropomorphism in service provision: A meta-analysis of physical robots, chatbots, and other AI. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 632–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, H. The evaluation of affection in human-robot interaction. Kybernetes 2016, 45, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. Intimacy: The Need to Be Close; Doubleday & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Wallach, W.; Smit, I. Why machine ethics? IEEE Intell. Syst. 2006, 21, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.A.; Walker, W.H. Prologue: Archaeology, animism and non-human agents. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2008, 15, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, D. Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Trafton, J.G.; McCurry, J.M.; Zish, K.; Frazier, C.R. The perception of agency. ACM Trans. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2024, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.; Young, L.; Waytz, A. Mind perception is the essence of morality. Psychol. Inq. 2012, 23, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sytsma, J.; Machery, E. The two sources of moral standing. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2012, 3, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. From warranty voids to uprising advocacy: Human action and the perceived moral patiency of social robots. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 670503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhail, J. Universal moral grammar: Theory, evidence and the future. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.M.; Axinn, S. The morality of autonomous robots. J. Mil. Ethics 2013, 12, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, R.; Sapienza, A. The Role of Trust in Dependence Networks: A Case Study. Information 2023, 14, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkle, S. Authenticity in the age of digital companions. Interact. Stud. 2007, 8, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C.; Tamò, A.; Guzman, A. Communicating with robots: ANTalyzing the interaction between healthcare robots and humans with regards to privacy. In Human-Machine Communication: Rethinking Communication, Technology, and Ourselves; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, C.; Tamó-Larrieux, A. The Robot Privacy Paradox: Understanding How Privacy Concerns Shape Intentions to Use Social Robots. Hum.-Mach. Commun. 2020, 1, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Dinev, T.; Smith, H.J.; Hart, P. Examining the formation of individual’s privacy concerns: Toward an integrative view. In Proceedings of the ICIS 2008 Proceedings, Paris, France, 14–17 December 2008; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Koops, B.J.; Leenes, R. Privacy regulation cannot be hardcoded. A critical comment on the ‘privacy by design’provision in data-protection law. Int. Rev. Law Comput. Technol. 2014, 28, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, D.; Richard Wohl, R. Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konijn, E.A.; Utz, S.; Tanis, M.; Barnes, S.B. Parasocial interactions and paracommunication with new media characters. Mediat. Interpers. Commun. 2008, 1, 191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, D.C. Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychol. 2002, 4, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yang, H. Understanding adoption of intelligent personal assistants: A parasocial relationship perspective. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2018, 118, 618–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.; Goldhoorn, C. Horton and Wohl revisited: Exploring viewers’ experience of parasocial interaction. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 1104–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; Bowman, N.D. Avatars are (sometimes) people too: Linguistic indicators of parasocial and social ties in player–avatar relationships. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L.I. Fostering consumer–brand relationships in social media environments: The role of parasocial interaction. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhang, S.; Wen, F.; Liu, K. How loneliness leads to the conversational AI usage intention: The roles of anthropomorphic interface, para-social interaction. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimmt, C.; Hartmann, T.; Schramm, H. Parasocial interactions and relationships. In Psychology of Entertainment; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Nah, H.S. The appeal of “real” in parasocial interaction: The effect of self-disclosure on message acceptance via perceived authenticity and liking. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 134, 107330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, T.; Quan-Haase, A. When Human-AI Interactions Become Parasocial: Agency and Anthropomorphism in Affective Design. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–6 June 2024; pp. 1068–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.J.; Park, E.; Sundar, S.S. Caregiving role in human–robot interaction: A study of the mediating effects of perceived benefit and social presence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, N.; Rao Hill, S.; Troshani, I. Artificial intelligence service agents: Role of parasocial relationship. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2022, 62, 1009–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, T.; de Leeuw, J.; Long, J.H. How movements of a non-humanoid robot affect emotional perceptions and trust. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2021, 13, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, P.A.; Billings, D.R.; Schaefer, K.E.; Chen, J.Y.; De Visser, E.J.; Parasuraman, R. A meta-analysis of factors affecting trust in human-robot interaction. Hum. Factors 2011, 53, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Cohen, J.; Mou, J. Human vs. AI: Understanding the impact of anthropomorphism on consumer response to chatbots from the perspective of trust and relationship norms. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, D.R.; Schaefer, K.E.; Chen, J.Y.; Hancock, P.A. Human-robot interaction: Developing trust in robots. In Proceedings of the Seventh Annual ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, Boston, MA, USA, 5–8 March 2012; pp. 109–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gompei, T.; Umemuro, H. Factors and development of cognitive and affective trust on social robots. In Proceedings of the Social Robotics: 10th International Conference, ICSR 2018, Qingdao, China, 28–30 November 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10, pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Youn, S.; Jin, S.V. In AI we trust?” The effects of parasocial interaction and technopian versus luddite ideological views on chatbot-based customer relationship management in the emerging “feeling economy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.D. Trust as social reality. Soc. Forces 1985, 63, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.S.; Sims, D.E.; Lazzara, E.H.; Salas, E. Trust in leadership: A multi-level review and integration. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 606–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, B.F.; Ullman, D. A multidimensional conception and measure of human-robot trust. In Trust in Human-Robot Interaction; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sundar, S.S.; Waddell, T.F.; Jung, E.H. The Hollywood robot syndrome media effects on older adults’ attitudes toward robots and adoption intentions. In Proceedings of the 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–10 March 2016; pp. 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Tamò-Larrieux, A.; Tamò-Larrieux, S.; Seyfried. Designing for Privacy and Its Legal Framework: Data Protection by Design and Default for the Internet of Things; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, C.; Schöttler, M.; Hoffmann, C.P. The privacy implications of social robots: Scoping review and expert interviews. Mob. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 412–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueben, M.; Aroyo, A.M.; Lutz, C.; Schmölz, J.; Van Cleynenbreugel, P.; Corti, A.; Agrawal, S.; Smart, W.D. Themes and research directions in privacy-sensitive robotics. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Workshop on Advanced Robotics and Its Social Impacts (ARSO), Genova, Italy, 27–29 September 2018; pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chuah, S.H.W.; Aw, E.C.X.; Yee, D. Unveiling the complexity of consumers’ intention to use service robots: An fsQCA approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 123, 106870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankton, N.; McKnight, D.H.; Thatcher, J.B. Incorporating trust-in-technology into expectation disconfirmation theory. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2014, 23, 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, X.; Wang, M.; Shen, H. What influences patients’ continuance intention to use AI-powered service robots at hospitals? The role of individual characteristics. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naneva, S.; Sarda Gou, M.; Webb, T.L.; Prescott, T.J. A systematic review of attitudes, anxiety, acceptance, and trust towards social robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2020, 12, 1179–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciechanowski, L.; Przegalinska, A.; Magnuski, M.; Gloor, P. In the shades of the uncanny valley: An experimental study of human–chatbot interaction. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 92, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, A.; Loi, M.; Viganò, E. In AI we trust incrementally: A multi-layer model of trust to analyze human-artificial intelligence interactions. Philos. Technol. 2020, 33, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Park, J.S. Do parasocial relationships and the quality of communication with AI shopping chatbots determine middle-aged women consumers’ continuance usage intentions? J. Consum. Behav. 2022, 21, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; p. 197. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2009; pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, S.Y.; Lin, Y.L.; Chang, B.F. The effects of intimacy and proactivity on trust in human-humanoid robot interaction. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Kim, S.S.; Agarwal, J. Internet users’ information privacy concerns (IUIPC): The construct, the scale, and a causal model. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004, 15, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, K. The Perception and Measurement of Human-Robot Trust. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA, 2013. Available online: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2688 (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Ashfaq, M.; Yun, J.; Yu, S.; Loureiro, S.M.C. I, Chatbot: Modeling the determinants of users’ satisfaction and continuance intention of AI-powered service agents. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 54, 101473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzl, C.; Chin, W.W. The case of partial least squares (PLS) path modeling in managerial accounting research. J. Manag. Control 2017, 28, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; Ohio University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolffgramm, M.R.; Corporaal, S.; Groen, A.J. Operators and their human–robot interdependencies: Implications of distinct job decision latitudes for sustainable work and high performance. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 12, 1442319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, H.; Lange, A.L.; Hafner, V.V.; Lazarides, R. How adaptive social robots influence cognitive, emotional, and self-regulated learning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, J.J.; Jeon, M. Exploring Emotional Connections: A Systematic Literature Review of Attachment in Human-Robot Interaction. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torras, C. Ethics of Social Robotics: Individual and Societal Concerns and Opportunities. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2024, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chae, Y.J.; Kim, D.; Lim, Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, C.; Park, S.K.; Nam, C. Effects of social behaviors of robots in privacy-sensitive situations. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 14, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guggemos, J.; Seufert, S.; Sonderegger, S.; Burkhard, M. Social robots in education: Conceptual overview and case study of use. In Orchestration of Learning Environments in the Digital World; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- González-González, C.S.; Violant-Holz, V.; Gil-Iranzo, R.M. Social robots in hospitals: A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, A.; Dursun, İ.; Kabadayi, E.T. Mitigating the effects of social desirability bias in self-report surveys: Classical and new techniques. In Applied Social Science Approaches to Mixed Methods Research; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 146–185. [Google Scholar]

- Koller, K.; Pankowska, P.K.; Brick, C. Identifying bias in self-reported pro-environmental behavior. Curr. Res. Ecol. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 4, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Burdet, E.; Si, W.; Yang, C.; Li, Y. Impedance learning for human-guided robots in contact with unknown environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 3705–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; Lu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, R. Compliance while resisting: A shear-thickening fluid controller for physical human-robot interaction. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2024, 43, 1731–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Items | Measurements | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intimacy | PAI1 | I feel that MOCCA is friendly to me, like a friend. | [98] |

| PAI2 | I think MOCCA is sociable and enjoys interacting with me. | ||

| PAI3 | I would like to have more conversations with MOCCA. | ||

| PAI4 | I feel emotionally close to MOCCA. | ||

| PAI5 | I believe that MOCCA and I share a close relationship. | ||

| Morality | PAM1 | MOCCA can think through whether a conversation is moral. | [18] |

| PAM2 | MOCCA feels obligated to engage in conversations in a moral way. | ||

| PAM3 | MOCCA has a sense for what is right and wrong. | ||

| PAM4 | MOCCA behaves according to moral rules in its conversations. | ||

| PAM5 | MOCCA would refrain from doing things that cause painful conversations. | ||

| Dependency | PAD1 | MOCCA can only behave how it is programmed to conversation. | [18] |

| PAD2 | MOCCA’s conversations are the result of its programming. | ||

| PAD3 | MOCCA can only do what humans tell it to do. | ||

| PAD4 | MOCCA would never engage in a conversation it was not programmed to do. | ||

| Information Privacy Risk | IPR1 | The personal information collected by MOCCA may be misused. | [56,99] |

| IPR2 | The personal information collected by MOCCA may be disclosed to others without my consent. | ||

| IPR3 | The personal information collected by MOCCA may be used improperly. | ||

| IPR4 | I believe it is difficult to ensure the confidentiality of personal information when using MOCCA. | ||

| IPR5 | I believe there is a risk that MOCCA may collect personal conversations and share them with others. | ||

| Parasocial Interaction | PSI1 | I feel like MOCCA understands me when I talk to it. | [38,62] |

| PSI2 | I feel like MOCCA knows I am involved in the conversation with it. | ||

| PSI3 | I feel like MOCCA knows that I am aware of it during our interaction. | ||

| PSI4 | I feel like MOCCA understands that I am focused on it during our conversation. | ||

| PSI5 | I feel like MOCCA knows how I am reacting to it during our conversation. | ||

| PSI6 | No matter what I say or do, MOCCA always responds to me. | ||

| Trust | TRS1 | I believe I can trust what MOCCA says. | [100] |

| TRS2 | I believe MOCCA will provide me with accurate information. | ||

| TRS3 | I believe MOCCA is honest. | ||

| TRS4 | I believe I can rely on MOCCA. | ||

| TRS5 | I believe MOCCA understands my needs and preferences. | ||

| TRS6 | I believe MOCCA wants to remember my interests. | ||

| TRS7 | I believe the services provided by MOCCA are trustworthy. | ||

| TRS8 | I believe MOCCA is trustworthy enough to share my personal information with it. | ||

| TRS9 | I believe the information provided by MOCCA is reliable. | ||

| Continuance Usage Intention | CUI1 | I will always enjoy using MOCCA in my daily life. | [88,101] |

| CUI2 | I intend to continue using MOCCA in the future. | ||

| CUI3 | I will use MOCCA more frequently in the future. | ||

| CUI4 | I will strongly recommend MOCCA to others. |

| Classification | Distribution | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 133 | 46.7% |

| Female | 152 | 53.3% | |

| Age | Under 20s (<20 years old) | 37 | 13.0% |

| 20s (20 to 29 years old) | 72 | 25.2% | |

| 30s (30 to 39 years old) | 72 | 25.2% | |

| 40s (40 to 49 years old) | 62 | 21.8% | |

| 50s (50 to 59 years old) | 39 | 13.7% | |

| 60 or Older (= or >60 years old) | 3 | 1.1% | |

| Educational Background | High school or below | 65 | 22.8% |

| Currently in College (excluding Junior College) | 73 | 25.6% | |

| College Graduate (excluding Junior College) | 71 | 24.9% | |

| Postgraduate or higher | 76 | 26.7% | |

| Occupational Background | Student | 53 | 18.6% |

| Company employee (IT industry) | 99 | 34.7% | |

| Company employee (non-IT industry) | 96 | 33.7% | |

| Housewife | 37 | 13.0% | |

| Usage Duration | Less than 1 month | 70 | 24.6% |

| 1 to 3 months | 58 | 20.4% | |

| 3 to 6 months | 53 | 18.6% | |

| 6 to 12 months | 46 | 16.1% | |

| Over 12 months | 58 | 20.3% | |

| Usage Frequency | Almost every day | 7 | 2.5% |

| 3 to 4 times a week | 53 | 18.6% | |

| Once a week | 111 | 38.9% | |

| 2 to 3 times a month | 55 | 19.3% | |

| Less than once a month | 59 | 20.7% | |

| Usage Purpose (multiple choices allowed) | Daily conversations and entertainment | 101 | 35.4% |

| Translation and writing assistance | 156 | 54.7% | |

| Information and knowledge search | 130 | 45.6% | |

| Professional questions and consultations | 76 | 26.7% | |

| Programming and technical support | 16 | 5.6% | |

| Creative and content creation assistance | 112 | 39.3% |

| Constructs | Items | λ | Cronbach’s α | rho_A | AVE | CR | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intimacy | PAI1 | 0.839 | 0.908 | 0.908 | 0.731 | 0.931 | 2.263 |

| PAI2 | 0.838 | 2.295 | |||||

| PAI3 | 0.868 | 2.682 | |||||

| PAI4 | 0.873 | 2.685 | |||||

| PAI5 | 0.856 | 2.492 | |||||

| Morality | PAM1 | 0.849 | 0.901 | 0.908 | 0.716 | 0.927 | 2.415 |

| PAM2 | 0.855 | 2.352 | |||||

| PAM3 | 0.823 | 2.191 | |||||

| PAM4 | 0.844 | 2.322 | |||||

| PAM5 | 0.862 | 2.359 | |||||

| Dependency | PAD1 | 0.818 | 0.855 | 0.864 | 0.696 | 0.902 | 1.879 |

| PAD2 | 0.821 | 1.983 | |||||

| PAD3 | 0.850 | 2.054 | |||||

| PAD4 | 0.848 | 1.916 | |||||

| Information Privacy Risk | IPR1 | 0.830 | 0.883 | 0.884 | 0.681 | 0.914 | 2.137 |

| IPR2 | 0.824 | 2.074 | |||||

| IPR3 | 0.822 | 2.103 | |||||

| IPR4 | 0.827 | 2.055 | |||||

| IPR5 | 0.823 | 2.004 | |||||

| Parasocial Interaction | PSI1 | 0.834 | 0.904 | 0.904 | 0.675 | 0.926 | 2.304 |

| PSI2 | 0.806 | 2.024 | |||||

| PSI3 | 0.824 | 2.249 | |||||

| PSI4 | 0.833 | 2.307 | |||||

| PSI5 | 0.808 | 2.109 | |||||

| PSI6 | 0.823 | 2.205 | |||||

| Trust | TRS1 | 0.781 | 0.938 | 0.939 | 0.668 | 0.948 | 2.140 |

| TRS2 | 0.812 | 2.368 | |||||

| TRS3 | 0.804 | 2.331 | |||||

| TRS4 | 0.843 | 2.691 | |||||

| TRS5 | 0.828 | 2.581 | |||||

| TRS6 | 0.808 | 2.339 | |||||

| TRS7 | 0.833 | 2.636 | |||||

| TRS8 | 0.841 | 2.704 | |||||

| TRS9 | 0.804 | 2.291 | |||||

| Continuance Usage Intention | CUI1 | 0.834 | 0.847 | 0.847 | 0.685 | 0.897 | 1.944 |

| CUI2 | 0.810 | 1.771 | |||||

| CUI3 | 0.834 | 1.957 | |||||

| CUI4 | 0.832 | 1.874 |

| Constructs | PAI | PAM | PAD | IPR | PSI | TRS | CUI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intimacy | 0.855 | 0.547 | 0.545 | 0.419 | 0.363 | 0.465 | 0.423 |

| Morality | 0.374 | 0.846 | 0.562 | 0.473 | 0.353 | 0.426 | 0.582 |

| Dependency | −0.372 | −0.404 | 0.835 | 0.485 | 0.442 | 0.484 | 0.525 |

| Information Privacy Risk | −0.406 | −0.447 | 0.369 | 0.825 | 0.425 | 0.499 | 0.453 |

| Parasocial Interaction | 0.477 | 0.441 | −0.395 | −0.434 | 0.821 | 0.457 | 0.423 |

| Trust | 0.539 | 0.397 | −0.319 | −0.431 | 0.519 | 0.817 | 0.411 |

| Continuance Usage Intention | 0.371 | 0.407 | −0.312 | −0.363 | 0.477 | 0.490 | 0.828 |

| Endogenous Variables | R Square (R2) | R Square Adjusted | Q2 | Exogenous Variables | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parasocial Interaction (PSI) | 0.399 | 0.388 | 0.264 | PAI | 0.032 |

| PAM | 0.029 | ||||

| PAD | 0.023 | ||||

| IPR | 0.019 | ||||

| Trust (TRS) | 0.365 | 0.356 | 0.240 | PAI | 0.181 |

| PAM | 0.025 | ||||

| PAD | 0.002 | ||||

| IPR | 0.041 | ||||

| Continuance Usage Intention (CUI) | 0.308 | 0.303 | 0.204 | PSI | 0.098 |

| TRS | 0.116 |

| Parameters | Path Coef. (β) | t-Value | p-Value | 95% CI | Supported? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | |||||

| Direct Effect (Path) | ||||||

| H1: PAI → PSI | 0.172 ** | 2.763 | 0.006 | 0.053 | 0.294 | Yes |

| H2: PAM → PSI | 0.159 ** | 2.797 | 0.005 | 0.048 | 0.270 | Yes |

| H3: PAD → PSI | −0.134 ** | 2.603 | 0.009 | −0.238 | −0.037 | Yes |

| H4: IPR → PSI | −0.129 * | 2.237 | 0.025 | −0.241 | −0.018 | Yes |

| H5: PAI → TRS | 0.390 *** | 7.392 | 0.000 | 0.281 | 0.491 | Yes |

| H6: PAM → TRS | 0.149 ** | 2.604 | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.261 | Yes |

| H7: PAD → TRS | −0.044 (ns) | 0.793 | 0.428 | −0.155 | 0.060 | No |

| H8: IPR → TRS | −0.190 ** | 3.324 | 0.001 | −0.302 | −0.080 | Yes |

| H9: TRS → PSI | 0.265 *** | 4.476 | 0.000 | 0.148 | 0.377 | Yes |

| H10: PSI → CUI | 0.305 *** | 5.614 | 0.000 | 0.194 | 0.410 | Yes |

| H11: TRS → CUI | 0.332 *** | 6.050 | 0.000 | 0.224 | 0.440 | Yes |

| Specific Indirect Effect (Mediation Path) | ||||||

| PAI → PSI → CUI | 0.052 * | 2.429 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.099 | Yes |

| PAM → PSI → CUI | 0.049 * | 2.356 | 0.019 | 0.013 | 0.093 | Yes |

| PAD → PSI → CUI | −0.041* | 2.228 | 0.026 | −0.082 | −0.010 | Yes |

| IPR → PSI → CUI | −0.039 * | 2.090 | 0.037 | −0.078 | −0.005 | Yes |

| PAI → TRS → CUI | 0.129 *** | 4.848 | 0.000 | 0.080 | 0.185 | Yes |

| PAM → TRS → CUI | 0.049 * | 2.211 | 0.027 | 0.010 | 0.098 | Yes |

| PAD → TRS → CUI | −0.014 (ns) | 0.783 | 0.434 | −0.054 | 0.020 | No |

| IPR → TRS → CUI | −0.063 ** | 2.887 | 0.004 | −0.110 | −0.024 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Cho, H.-K.; Kim, M.-Y. A Study on Factors Affecting the Continuance Usage Intention of Social Robots with Episodic Memory: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5334. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105334

Yang Y, Cho H-K, Kim M-Y. A Study on Factors Affecting the Continuance Usage Intention of Social Robots with Episodic Memory: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Perspective. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(10):5334. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105334

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yi, Hye-Kyung Cho, and Min-Yong Kim. 2025. "A Study on Factors Affecting the Continuance Usage Intention of Social Robots with Episodic Memory: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Perspective" Applied Sciences 15, no. 10: 5334. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105334

APA StyleYang, Y., Cho, H.-K., & Kim, M.-Y. (2025). A Study on Factors Affecting the Continuance Usage Intention of Social Robots with Episodic Memory: A Stimulus–Organism–Response Perspective. Applied Sciences, 15(10), 5334. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15105334