Towards a System Dynamics Framework for Human–Machine Learning Decisions: A Case Study of New York Citi Bike

Abstract

1. Introduction

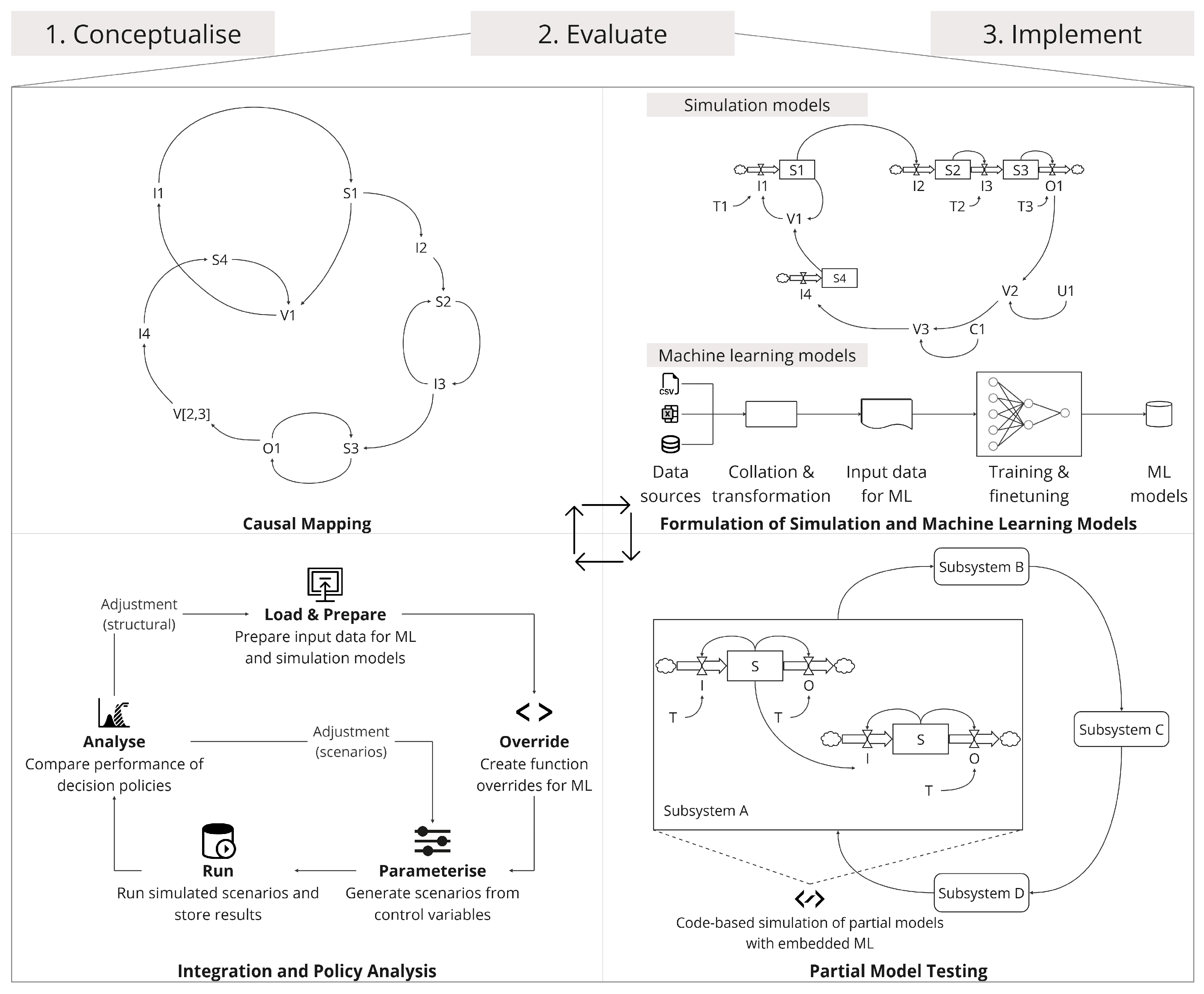

2. Modelling Framework

3. The Bike-Share Case

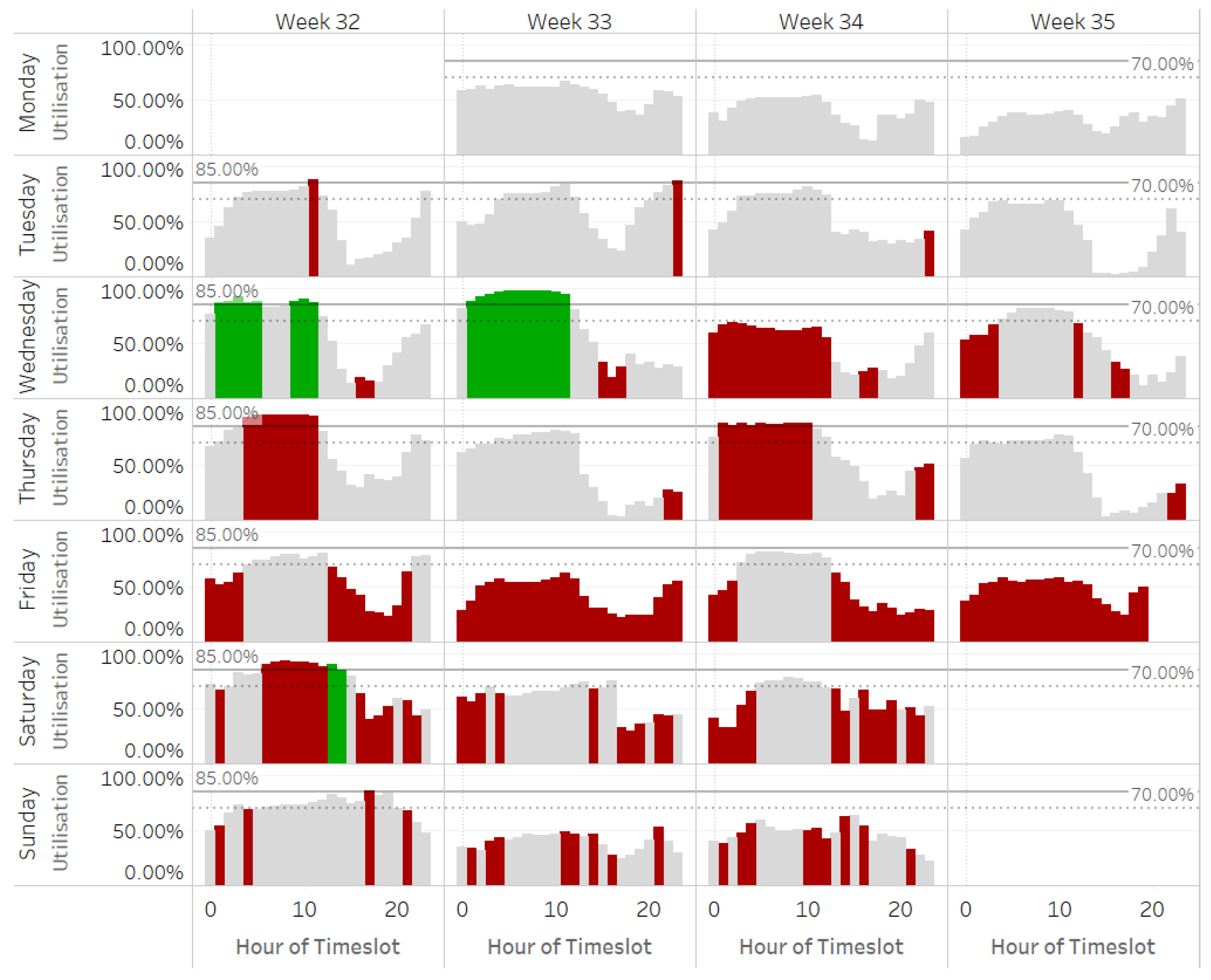

3.1. Business Context and Problem Illustration

3.2. Data

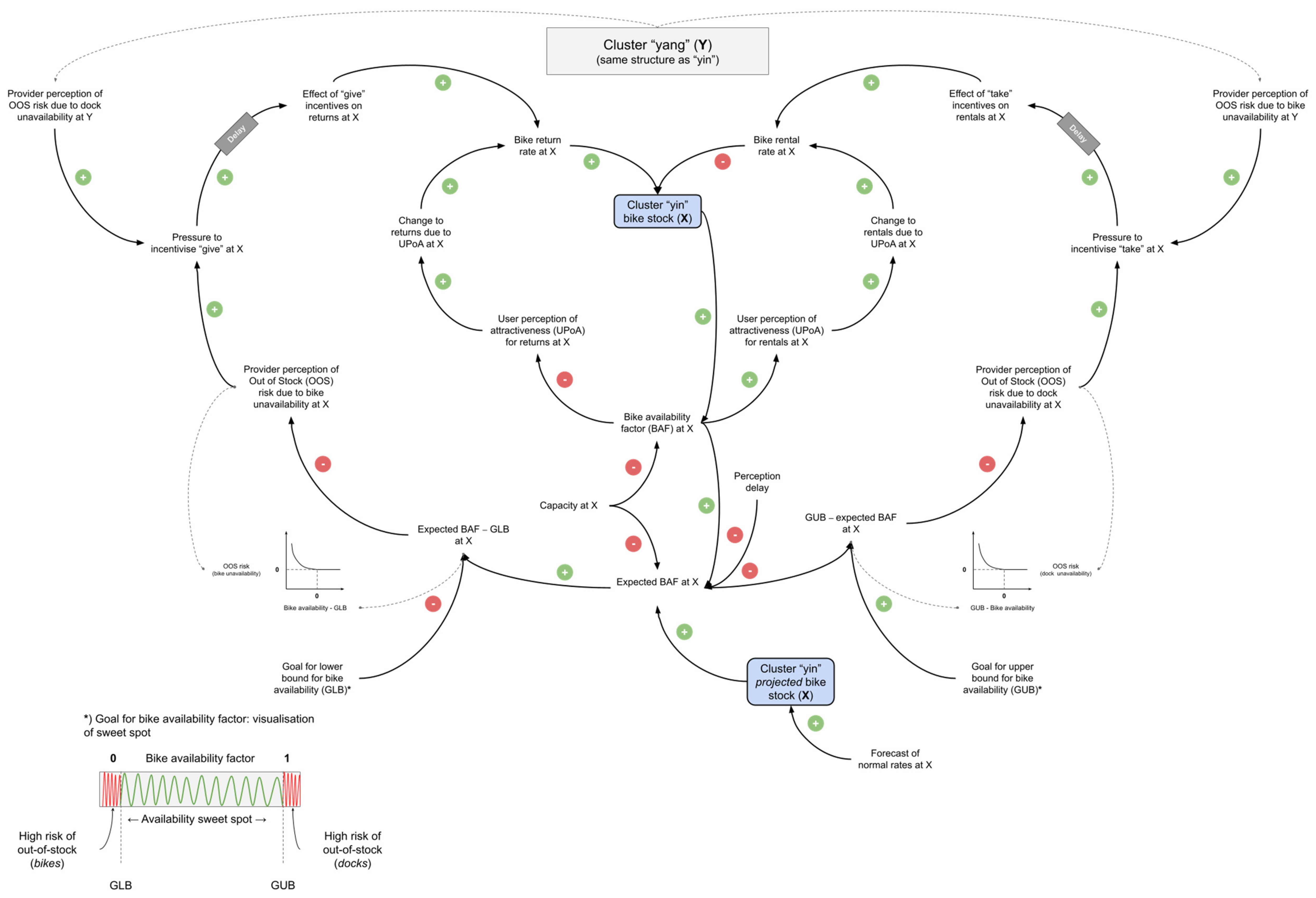

3.3. Evaluation—Causal Mapping

3.4. Evaluation—Formulation of Simulation and ML Models

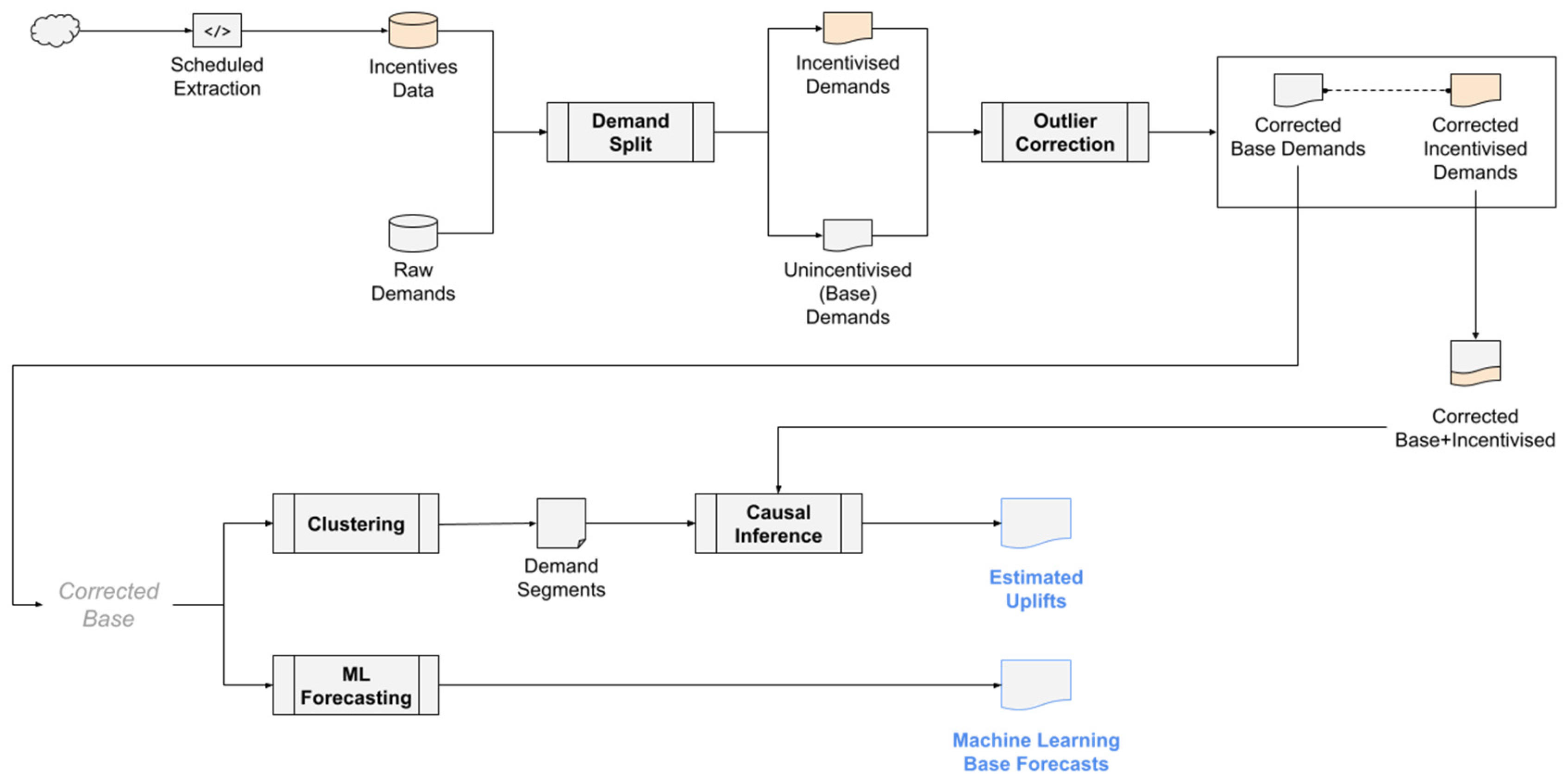

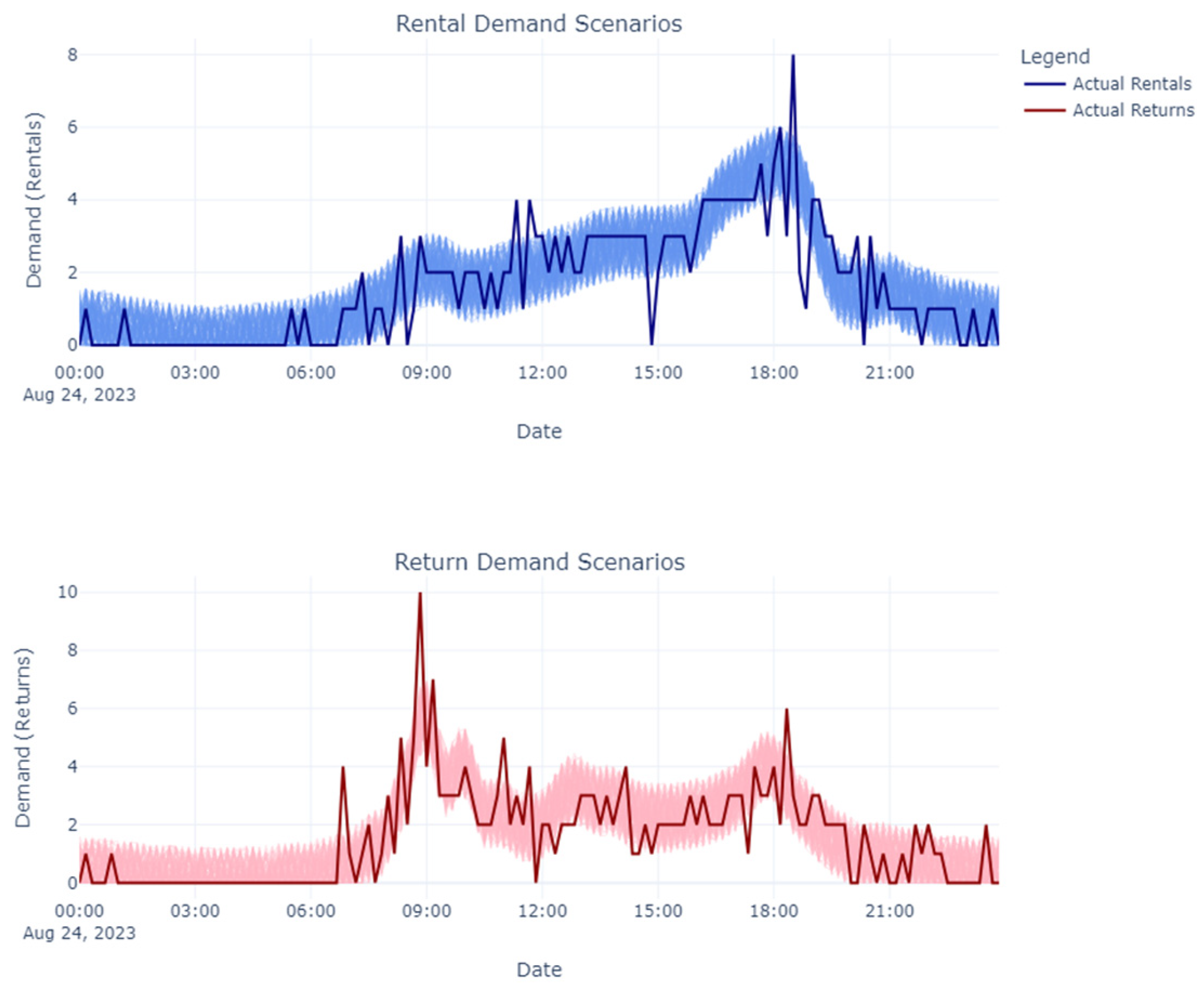

3.4.1. Demand Forecasting

Demand De-Censoring

Machine Learning Forecast

3.4.2. Causal Inference

- Data: Hourly bike utilisation for each station (Bike utilisation (percentage of bikes rented) = Dock availability/Capacity).

- Steps:

- Load and preprocess the data:

- ○

- Pivot the dataset to create a 24 h utilisation vector for each station and day.

- Normalise the utilisation vectors for each station using MinMax scaling.

- For each pair of stations (21 pairs for seven stations):

- ○

- Extract the 24 h utilisation vectors for corresponding days for both stations.

- ○

- Calculate the L2 distance between the normalised vectors for each day.

- ○

- Compute the average L2 distance across all days as the final similarity metric for the station pair.

- Store the average L2 distances for all station pairs in a table, sorted by similarity (lowest to highest distance).

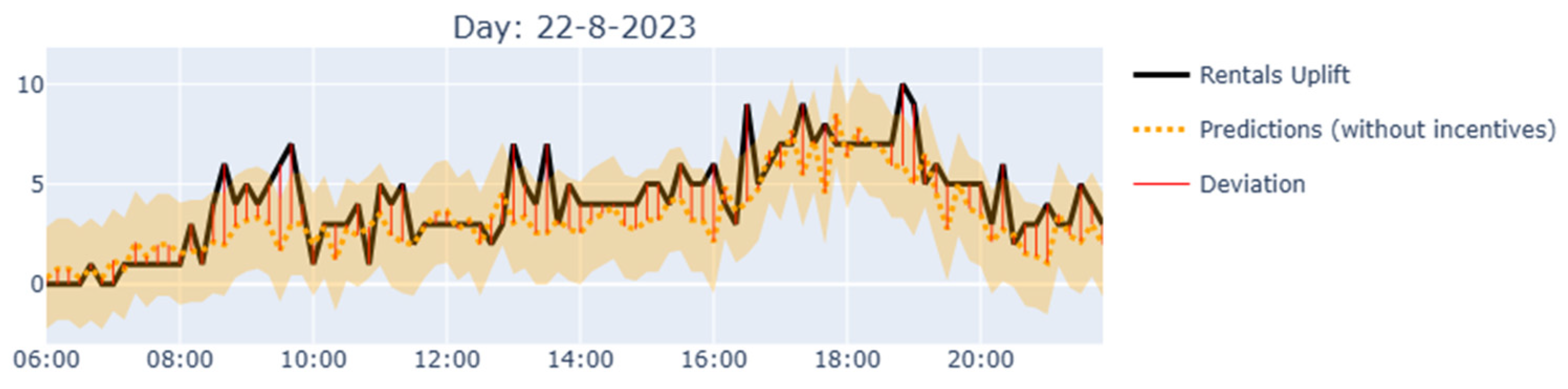

- Data: Base (unincentivised) and incentivised rental/return demands for each station.

- Steps:

- Prepare the Data:

- ○

- Filter and rename the columns to distinguish between base and incentivised demands (e.g., “Rentals Normal” for base, “Rentals Uplift” for incentivised).

- ○

- Pivot the data to create a time series of rentals and returns for each station, with pre-intervention values using base demand and post-intervention values using incentivised demand.

- ○

- Define the pre- and post-intervention periods based on the intervention days.

- Run the Causal Impact Model:

- ○

- Use the base demands from correlated stations (identified in Stage 1) as covariates and the incentivised demand for the target station as the response series.

- ○

- The model infers the base demand for the target station during the post-intervention period (had no incentives been applied).

- Collate and Average Results:

- ○

- Collect the target station’s inferred rental/return uplift (i.e., the difference between the incentivised and predicted base demand) across all intervention days.

- ○

- Average the results to create a typical week, showing hourly estimated percentage uplifts for rentals and returns.

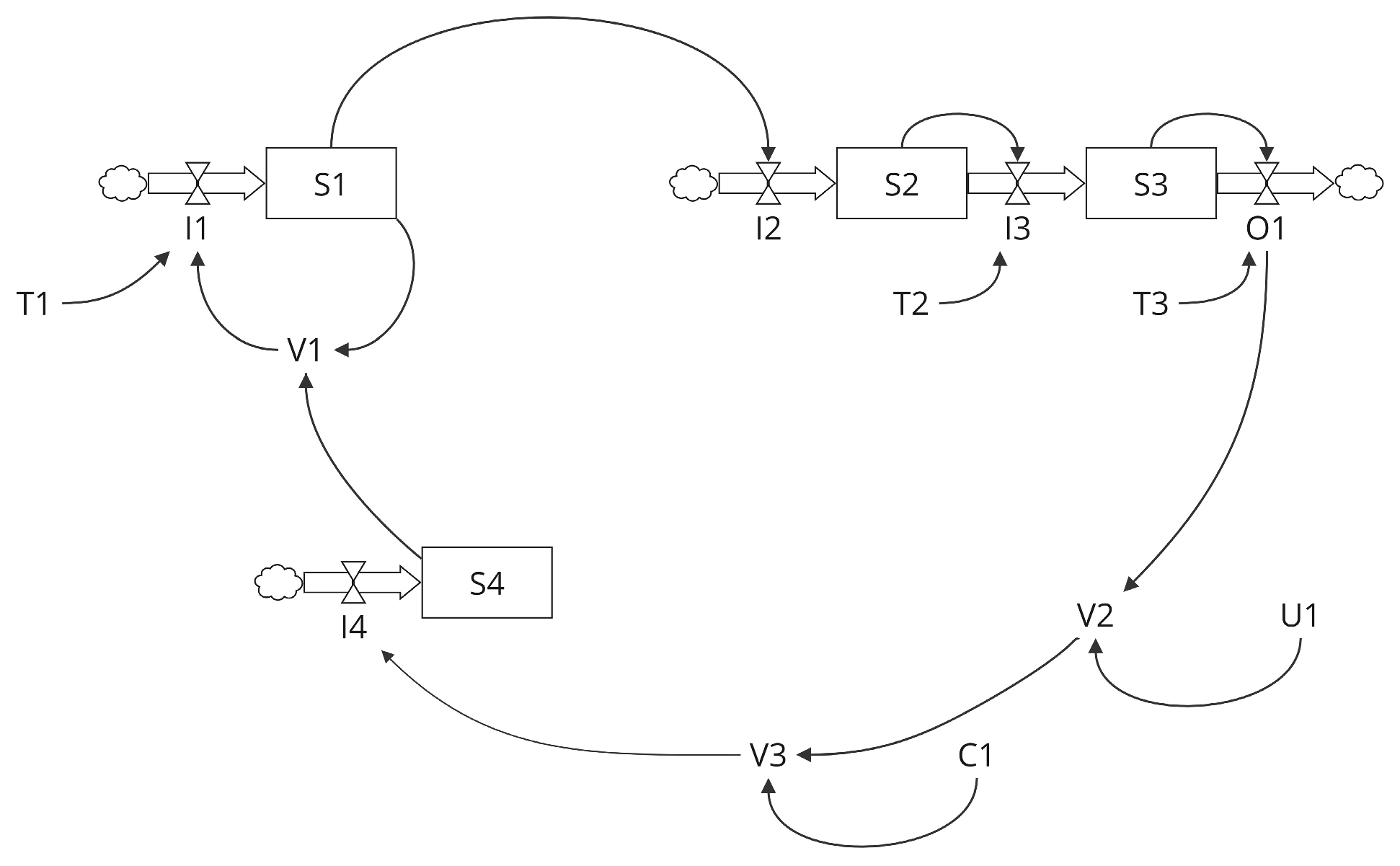

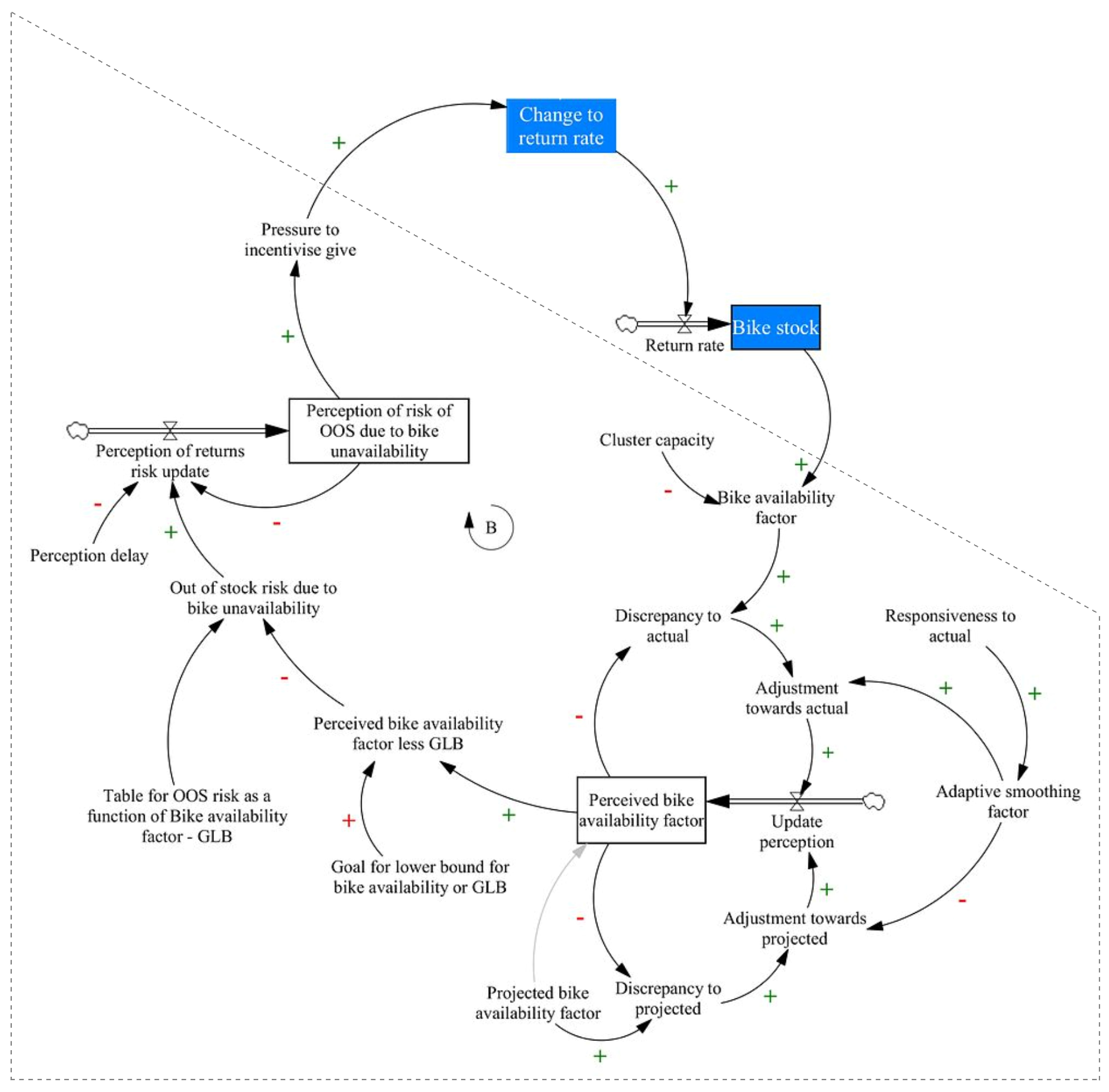

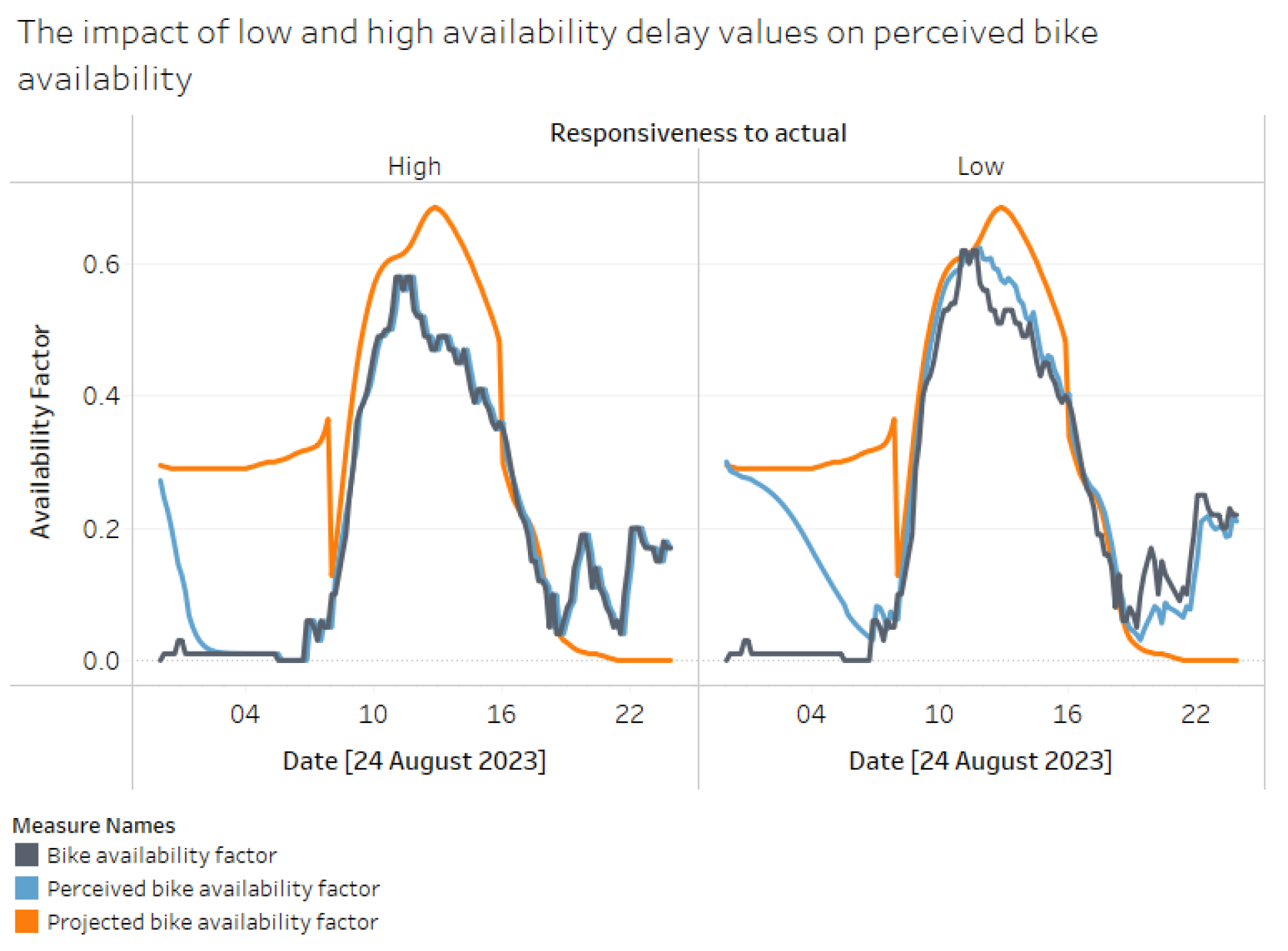

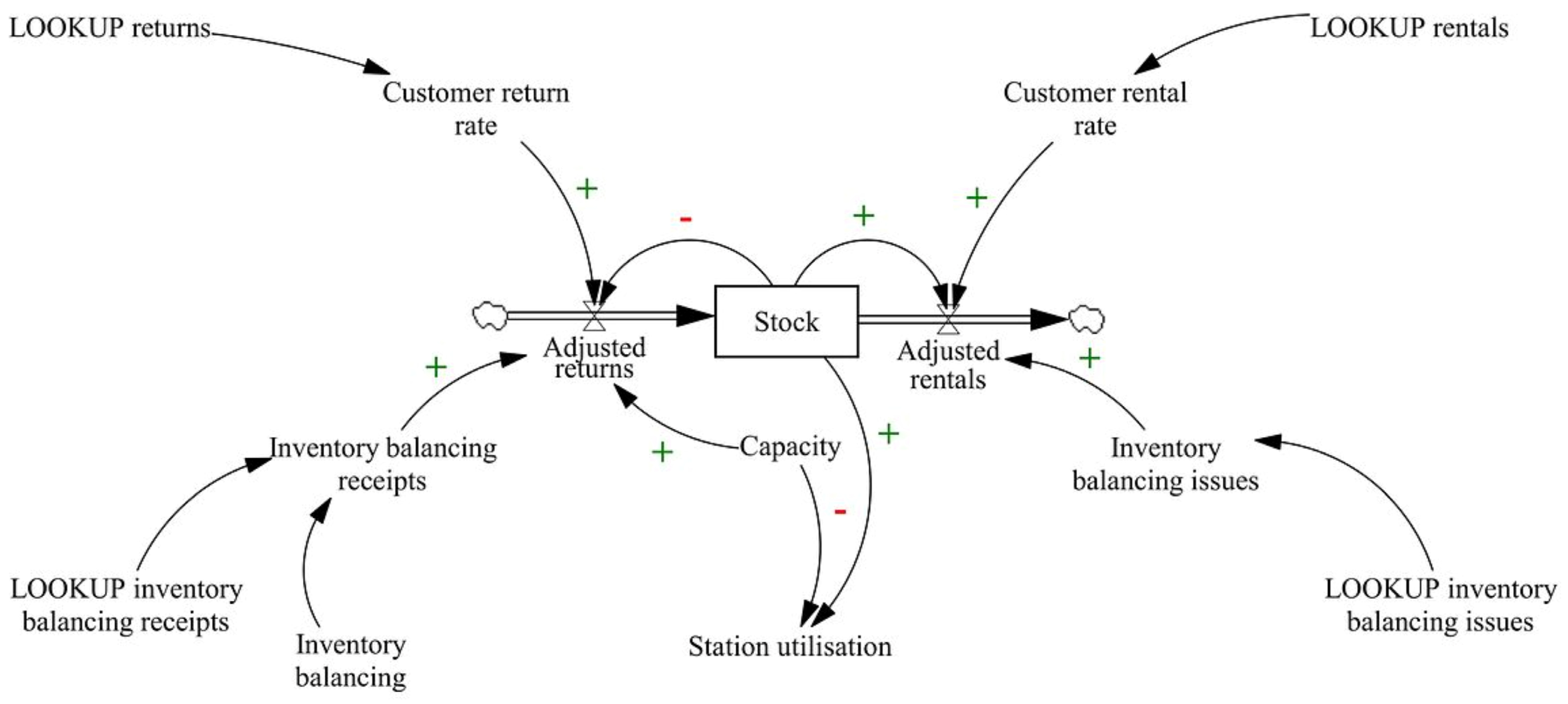

3.4.3. Stocks and Flows Modelling

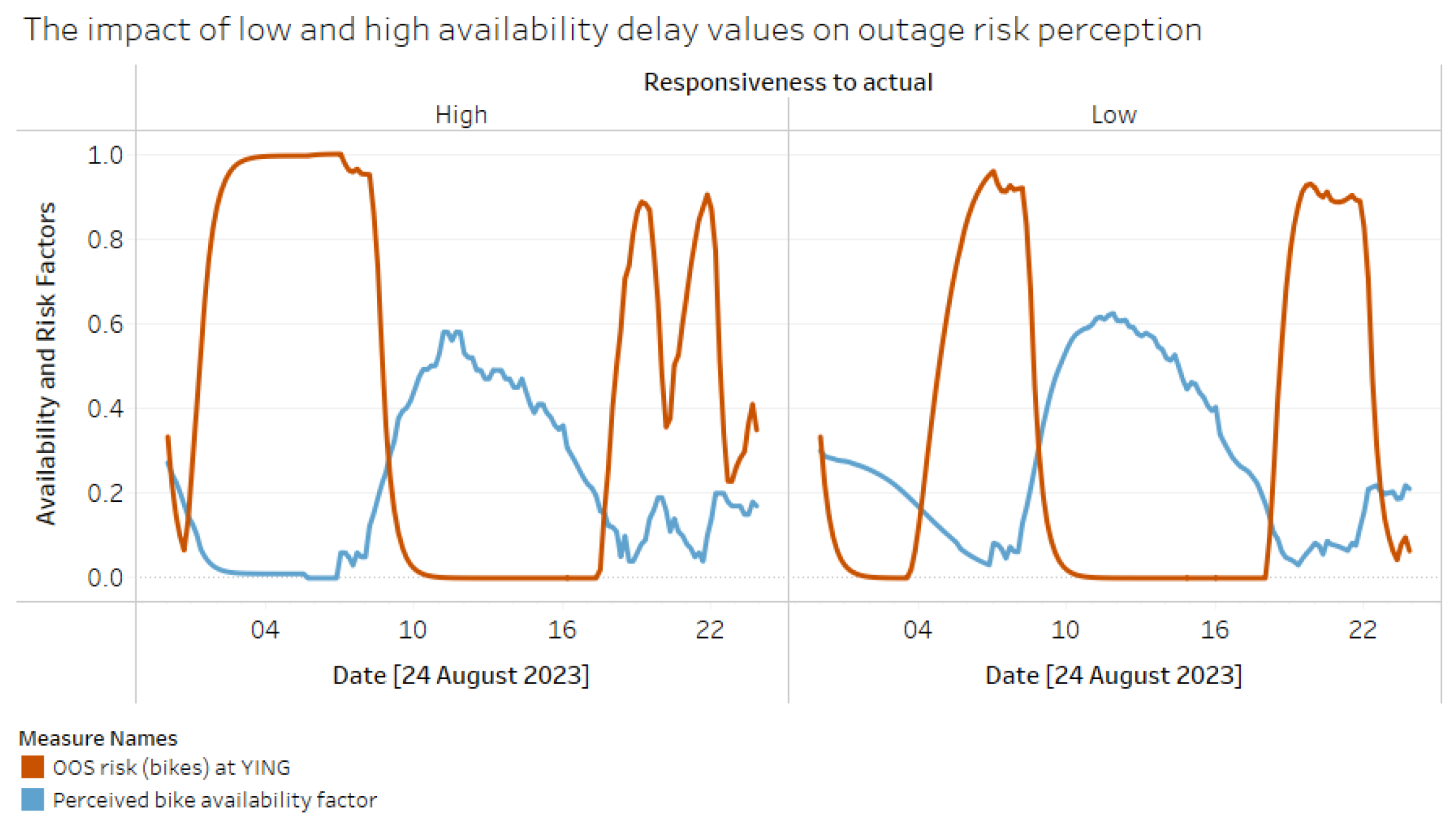

- 1.

- Perceived bike availability factor = Perceived bike availability factor + Update perception ×

- 2.

- Initial Perceived bike availability factor = Projected bike availability factor.

- 3.

- Update perception = Adjustment towards actual + Adjustment towards projected.

- 4.

- Adjustment towards actual = Adaptive smoothing factor × Discrepancy to actual.

- 5.

- Adaptive smoothing factor = (time, Responsiveness to actual)

- 6.

- Discrepancy to actual = Bike availability factor − Perceived bike availability factor

- 7.

- Adjustment towards projected = (1 − Adaptive smoothing factor) × Discrepancy to projected.

- 8.

- Discrepancy to projected = Projected bike availability factor − Perceived bike availabil-ity factor.

- 9.

- Projected bike availability factor = (rental and return demands, other factors).

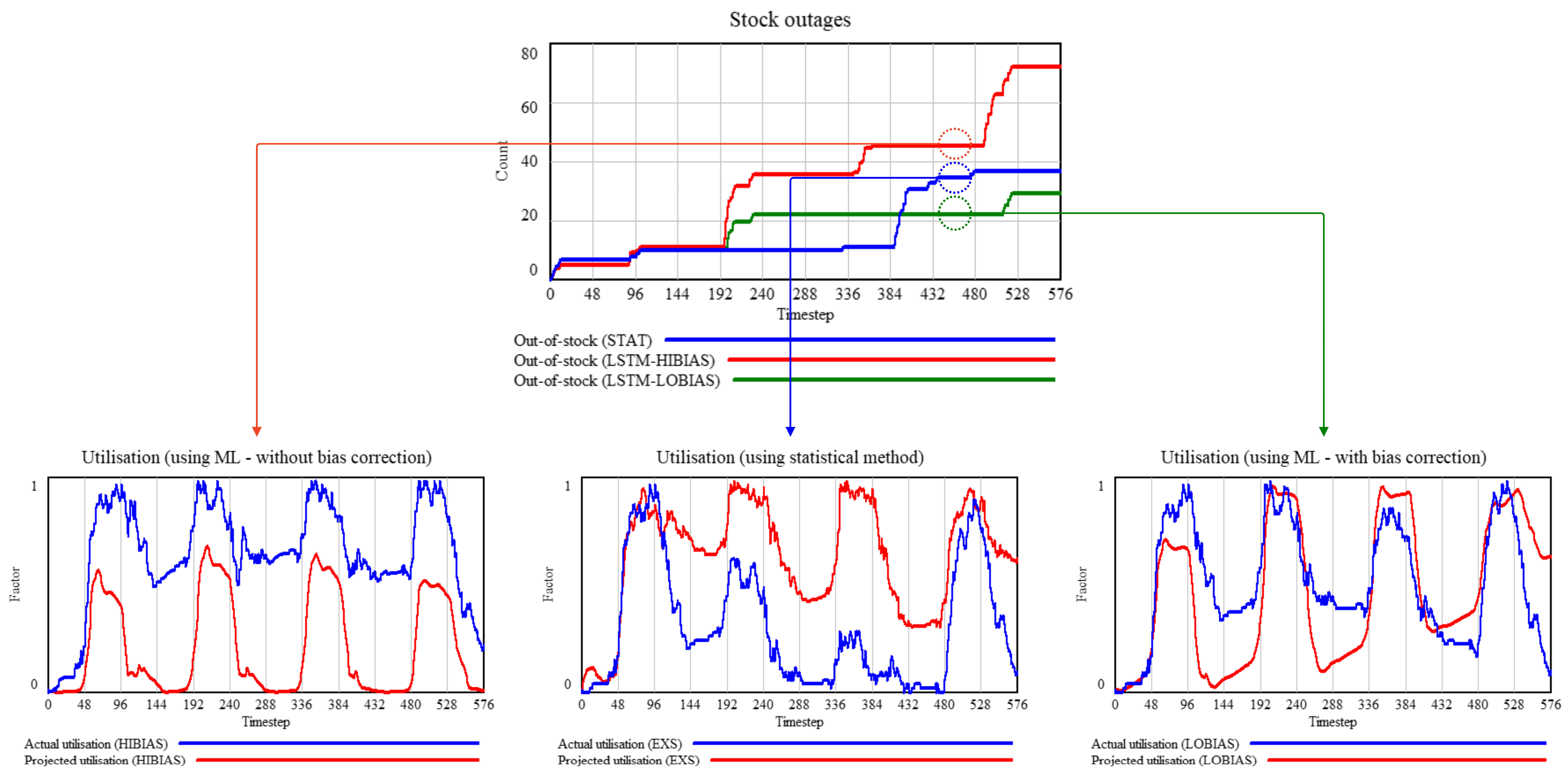

3.5. Evaluation—Partial Model Testing

- Calculation of Just-in-Time Inventory Balancing (Receipts and Issues):

- ○

- Run the ML and STAT predictions through a simplified stocks and flows structure to compute projected stocks.

- ○

- Whenever an outage occurs (either lack of bikes or docks), record the volume as a planned balancing receipt or issue.

- Calculation of the Process Metric: Total Outages with Just-in-Time Balancing (ML vs. STAT Predictions):

- ○

- Run actual or simulated rental and return demands through a structure that models actual stock (aligned with the projected stock structure).

- ○

- Use planned receipts and issues (from the previous step) as lookups to adjust rentals and returns.

- ○

- Record the bikes and docks outages.

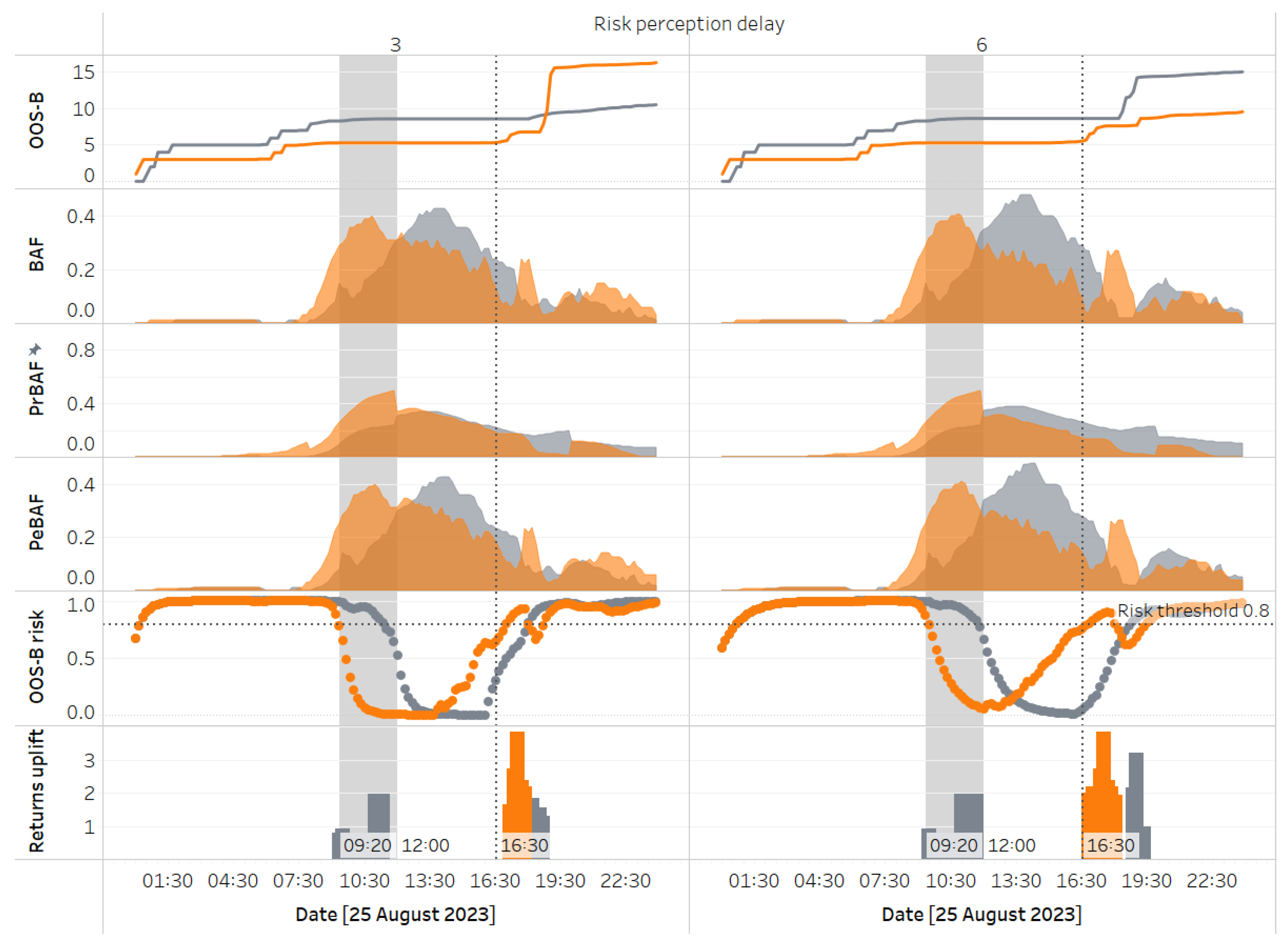

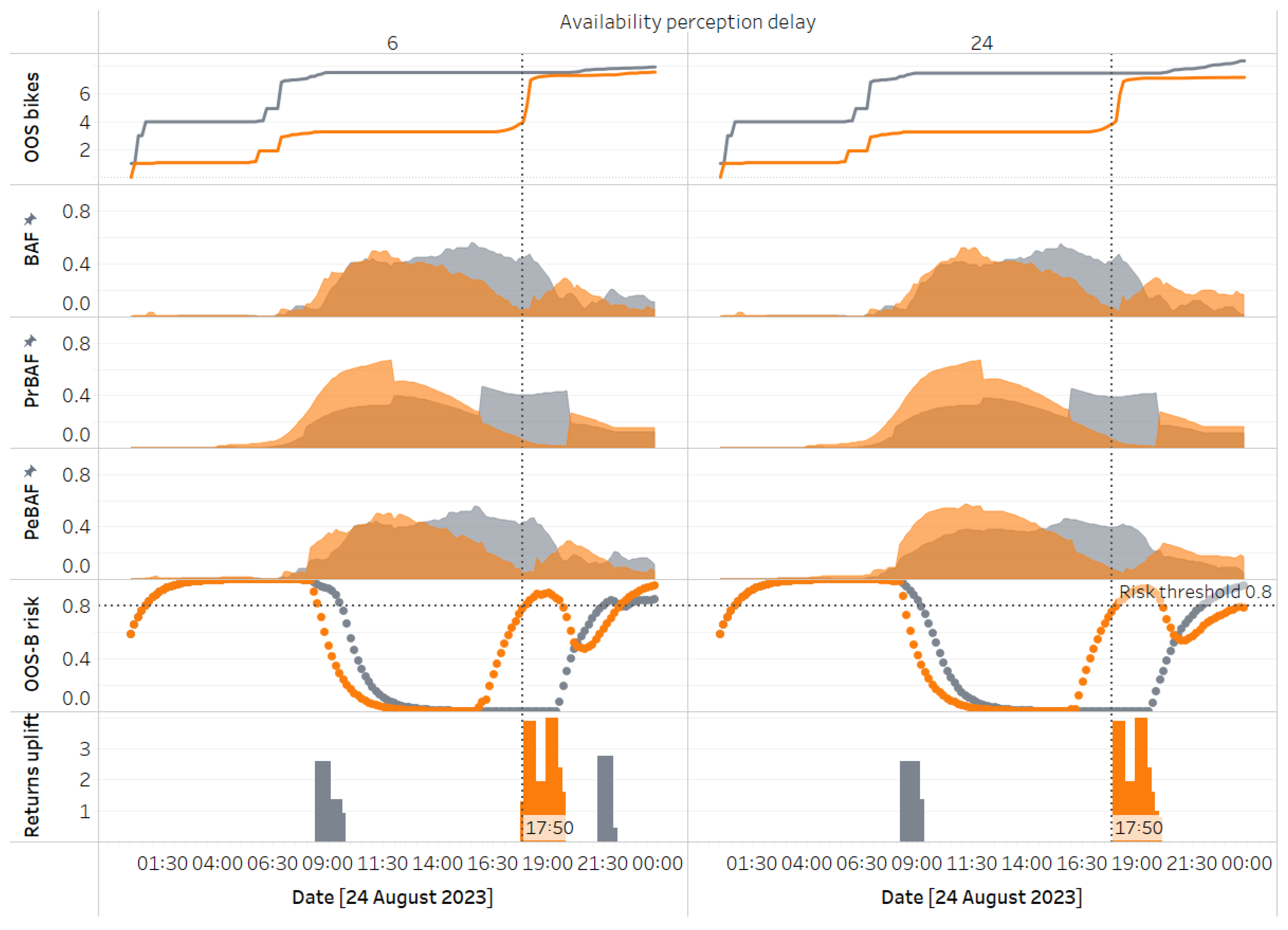

3.6. Evaluation—Integration and Policy Analysis

3.6.1. Starting Inventory Policy

3.6.2. Simulation of Performance Across the Fitness Landscape

3.7. Insights and Implications

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Model Architecture |

|

| Features Used |

|

| Optional Features |

|

| Model Parameters |

|

| Loss Function |

|

| Optimisation |

|

| Data Preprocessing |

|

| Training Process |

|

| Evaluation Metrics |

|

| Implementation |

|

| Data Granularity |

|

| Forecasting Approach |

|

| Notable Features |

|

| Reproducibility |

|

References

- Raschka, S. Build a Large Language Model from Scratch; Manning Publications: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2024; 400p. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, T.W. How Human-Computer “Superminds” Are Redefining the Future of Work. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2018, 59, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Gans, J.S.; Goldfarb, A. What to Expect from Artificial Intelligence. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2017, 58, 23. Available online: https://sloanreview-mit-edu.plymouth.idm.oclc.org/article/what-to-expect-from-artificial-intelligence/ (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Saenz, M.J.; Revilla, E.; Simón, C. Designing AI Systems With Human-Machine Teams. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2020, 61, 1–5. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/designing-ai-systems-with-human-machine-teams/ (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Raisch, S.; Krakowski, S. Artificial Intelligence and Management: The Automation–Augmentation Paradox. AMR 2021, 46, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Mitchell, T. What can machine learning do? Workforce implications. Science 2017, 358, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, D. Polanyi’s Paradox and the Shape of Employment Growth; Report No.: 20485; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w20485 (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Agrawal, A.; Gans, J.; Goldfarb, A. Power and Prediction: The Disruptive Economics of Artificial Intelligence; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2022; 288p. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson, E. The Turing Trap: The Promise & Peril of Human-Like Artificial Intelligence. Daedalus 2022, 151, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S. Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle over Technology and Prosperity, 1st ed.; Public Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2023; 560p. [Google Scholar]

- Kambhampati, S. Polanyi’s Revenge and AI’s New Romance with Tacit Knowledge. Commun. ACM 2021, 64, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebovitz, S.; Levina, N.; Lifshitz-Assaf, H. Is AI Ground Truth Really “True?” The Dangers of Training and Evaluating AI Tools Based on Experts’ Know-What. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 2021, 45, 1501–1526. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3839601 (accessed on 28 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Raghu, M.; Blumer, K.; Corrado, G.; Kleinberg, J.; Obermeyer, Z.; Mullainathan, S. The Algorithmic Automation Problem: Prediction, Triage, and Human Effort. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.12220. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, J. Don’t Confuse Digital with Digitization. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2019. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/dont-confuse-digital-with-digitization/ (accessed on 7 November 2022).

- Moser, C.; Hond, F.; den Lindebaum, D. What Humans Lose When We Let AI Decide. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2022, 63, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, G. Images of Organization; Updated edition; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; 520p. [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer, G. How to Stay Smart in a Smart World: Why Human Intelligence Still Beats Algorithms; Penguin: Portland, Oregon, 2022; 307p. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, T. ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web. The New Yorker, 2023. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/chatgpt-is-a-blurry-jpeg-of-the-web (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Babic, B.; Cohen, I.G.; Evgeniou, T.; Gerke, S. When Machine Learning Goes Off the Rails. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2021, 132–138. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/01/when-machine-learning-goes-off-the-rails (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Smith, B.C. The Promise of Artificial Intelligence: Reckoning and Judgment; Illustrated Edition; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; 184p. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, R. Big Data, New Epistemologies and Paradigm Shifts. Big Data Soc. 2014, 1, 2053951714528481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, P. A Few Useful Things to Know About Machine Learning. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.A. Adaptation on Rugged Landscapes. Manag. Sci. 1997, 43, 934–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, T.; Gerlach, J.P.; Pumplun, L.; Mesbah, N.; Peters, F.; Tauchert, C.; Nan, N.; Buxmann, P. Coordinating Human and Machine Learning for Effective Organizational Learning. MIS Q. 2021, 45, 1581–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Acqua, F.; McFowland, E., III; Mollick, E.R.; Lifshitz-Assaf, H.; Kellogg, K.; Rajendran, S.; Lakhani, K.R. Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper. 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4573321 (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Oliveira, G.N.; Sotomayor, J.L.; Torchelsen, R.P.; Silva, C.T.; Comba, J.L.D. Visual analysis of bike-sharing systems. Comput. Graph. 2016, 60, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Freund, D.; Shmoys, D.B. Bike Angels: An Analysis of Citi Bike’s Incentive Program. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies (COMPASS’ 18), New York, NY, USA, 20–22 June 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: International Bestseller; Wright, D., Ed.; Chelsea Green Publishing: Hartford, VT, USA, 2008; 240p. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of The Learning Organization; Revised & Updated edition; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2006; 445p. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, J.W. Industrial Dynamics. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1958, 36, 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pruyt, E. Small System Dynamics Models for Big Issues: Triple Jump Towards Real-World Complexity; TU Delft Library: Delft, The Netherlands, 2013; 324p. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, R.; Singh, N.S.; Schiratti, P.-R.; Semwanga, A.; Binyaruka, P.; Sachingongu, N.; Chama-Chiliba, C.M.; Chalabi, Z.; Borghi, J.; Blanchet, K. Mathematical modelling for health systems research: A systematic review of system dynamics and agent-based models. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morecroft, J.D. System dynamics: Portraying bounded rationality. Omega 1983, 11, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyneis, J.M. System dynamics for market forecasting and structural analysis. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2000, 16, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, D.; Georgiadis, P.; Iakovou, E. A system dynamics model for dynamic capacity planning of remanufacturing in closed-loop supply chains. Comput. Oper. Res. 2007, 34, 367–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, J.; Siegel, M. Advanced data analytics for system dynamics models using PySD. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference of the System Dynamics Society, Cambridge, MA, USA, 19–23 July 2015; System Dynamics Society: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.T.; Tu, Y.M.; Jeng, B. A Machine Learning Approach to Policy Optimization in System Dynamics Models. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edali, M. Pattern-oriented analysis of system dynamics models via random forests. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2022, 38, 135–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; 248p. [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran, G.; Palomino, M.A.; Knahl, M.; Siestrup, G. A modeling approach for measuring the performance of a human-AI collaborative process. Appl Sci. 2022, 12, 11642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiani, L.; Ottomanelli, M. A Dynamic Simulation based Model for Optimal Fleet Repositioning in Bike-sharing Systems. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 87, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowalekar, M.; Varakantham, P.; Ghosh, S.; Jena, S.; Jaillet, P. Online Repositioning in Bike Sharing Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Automated Planning and Scheduling, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 18–23 June 2017; Volume 27, pp. 200–208. Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICAPS/article/view/13824 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Legros, B. Dynamic repositioning strategy in a bike-sharing system; how to prioritise and how to rebalance a bike station. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 272, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Trick, M.; Varakantham, P. Robust Repositioning to Counter Unpredictable Demand in Bike Sharing Systems. In Proceedings of the 25th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence IJCAI 2016, New York, NY, USA, 9–15 July 2016; pp. 3096–3102. Available online: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sis_research/3456 (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Sterman, J.D. Business Dynamics; International edition; McGraw-Hill Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; 993p. [Google Scholar]

- Will, M.; Bertrand, J.; Fransoo, J.C. Operations management research methodologies using quantitative modeling. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morecroft, J.D.W. Strategic Modelling and Business Dynamics: A Feedback Systems Approach, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; 504p. [Google Scholar]

- Mitroff, I.I.; Betz, F.; Pondy, L.R.; Sagasti, F. On Managing Science in the Systems Age: Two Schemas for the Study of Science as a Whole Systems Phenomenon. Interfaces 1974, 4, 46–58. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25059093 (accessed on 22 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, J. Understanding the usage of dockless bike sharing in Singapore. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2018, 12, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.A.; Guzman, S.; Zhang, H. Bikesharing in Europe, the Americas, and Asia: Past, Present, and Future. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2143, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, A.; Santoni, M.; Bartók, G.; Mukerji, P.; Meenen, M.; Krause, A. Incentivizing Users for Balancing Bike Sharing Systems. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Austin, TX, USA, 25–30 January; 2015; Volume 29. Available online: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/9251 (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- El Sibai, R.; Challita, K.; Bou Abdo, J.; Demerjian, J. A New User-Based Incentive Strategy for Improving Bike Sharing Systems’ Performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2780. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/5/2780 (accessed on 6 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Makridakis, S.G.; Wheelwright, S.C.; Hyndman, R.J. Forecasting: Methods and Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1998; 923p. [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran, G.; Sasso, F.; Kepczynski, R.; Chiaraviglio, A. Improving Forecasts with Integrated Business Planning: From Short-Term to Long-Term Demand Planning Enabled by SAP IBP; Management for Professionals; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-05381-9 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Géron, A. Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems, 3rd ed.; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2019; 856p. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Deep Learning with Python, 2nd ed.; Manning: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2021; 504p. [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen, K.H.; Gallusser, F.; Koehler, J.; Remy, N.; Scott, S.L. Inferring causal impact using Bayesian structural time-series models. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2015, 9, 247–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morecroft, J.D.W. Rationality in the Analysis of Behavioral Simulation Models. Manag. Sci. 1985, 31, 900–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridakis, S.; Spiliotis, E.; Assimakopoulos, V. Statistical and Machine Learning forecasting methods: Concerns and ways forward. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Procedure | Description |

|---|---|

| Bias Correction Layer | |

| 1. Initialise the Layer | Create a trainable bias term initialised to zero. |

| 2. Forward Pass (Call Method) | For each prediction, adjust it by adding the bias term. |

| 3. Configuration Retrieval | Return the layer configuration. |

| Asymmetric Hybrid Loss Function | |

| 1. Initialise the Loss Function | Parameters: alpha: Weight for combining MSE and MAE. lambda_bias: Penalty for bias correction. lambda_over: Penalty for over-predictions. lambda_under: Penalty for under-predictions. local_corr: Whether to compute bias correction locally (per sample) or globally (batch-wise). |

| 2. Compute the Loss | Calculate prediction errors:

. Separate errors into over-predictions (positive) and under-predictions (negative). Calculate MAE with different penalties for over- and under-predictions. Calculate MSE for all errors. Combine MSE and MAE using the weighting parameter α. |

| 3. Bias Correction | Calculate the bias correction term, either locally (sample-wise) or globally (batch-wise). Add a penalty for bias to the loss, scaled by λ bias. |

| 4. Return Final Loss | Final loss is the weighted sum of MSE, MAE and the bias correction penalty. |

| 5. Configuration Retrieval | Return the loss function configuration, including all hyperparameters. |

| Model | MSE Rentals | MSE Returns | Bias Rentals | Bias Returns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT | 1.46 | 1.27 | 0 | 59 |

| ML HI-B | 1.05 | 1.03 | 18 | −59 |

| ML LO-B | 1.05 | 1.02 | 17 | 29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sankaran, G.; Palomino, M.A.; Knahl, M.; Siestrup, G. Towards a System Dynamics Framework for Human–Machine Learning Decisions: A Case Study of New York Citi Bike. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10647. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210647

Sankaran G, Palomino MA, Knahl M, Siestrup G. Towards a System Dynamics Framework for Human–Machine Learning Decisions: A Case Study of New York Citi Bike. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(22):10647. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210647

Chicago/Turabian StyleSankaran, Ganesh, Marco A. Palomino, Martin Knahl, and Guido Siestrup. 2024. "Towards a System Dynamics Framework for Human–Machine Learning Decisions: A Case Study of New York Citi Bike" Applied Sciences 14, no. 22: 10647. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210647

APA StyleSankaran, G., Palomino, M. A., Knahl, M., & Siestrup, G. (2024). Towards a System Dynamics Framework for Human–Machine Learning Decisions: A Case Study of New York Citi Bike. Applied Sciences, 14(22), 10647. https://doi.org/10.3390/app142210647