Printing the Future Layer by Layer: A Comprehensive Exploration of Additive Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 4.0

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Basics of Additive Manufacturing

2.1. Overview of Additive Manufacturing Processes

2.2. Materials Used in the Printing Processes

3. Current Status of 3D Printing in Industry 4.0

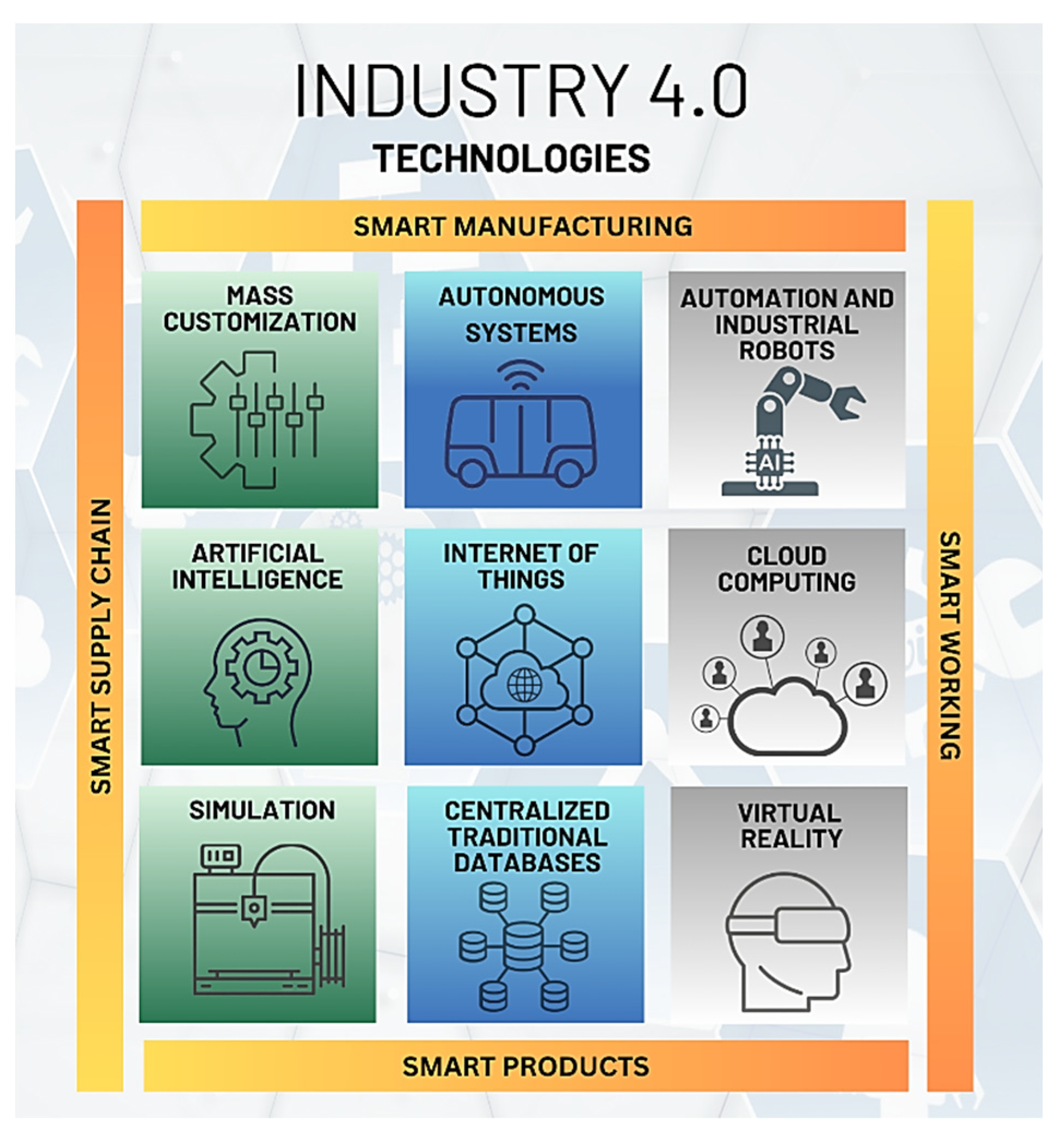

3.1. Technological Evolution in the Context of Industry 4.0

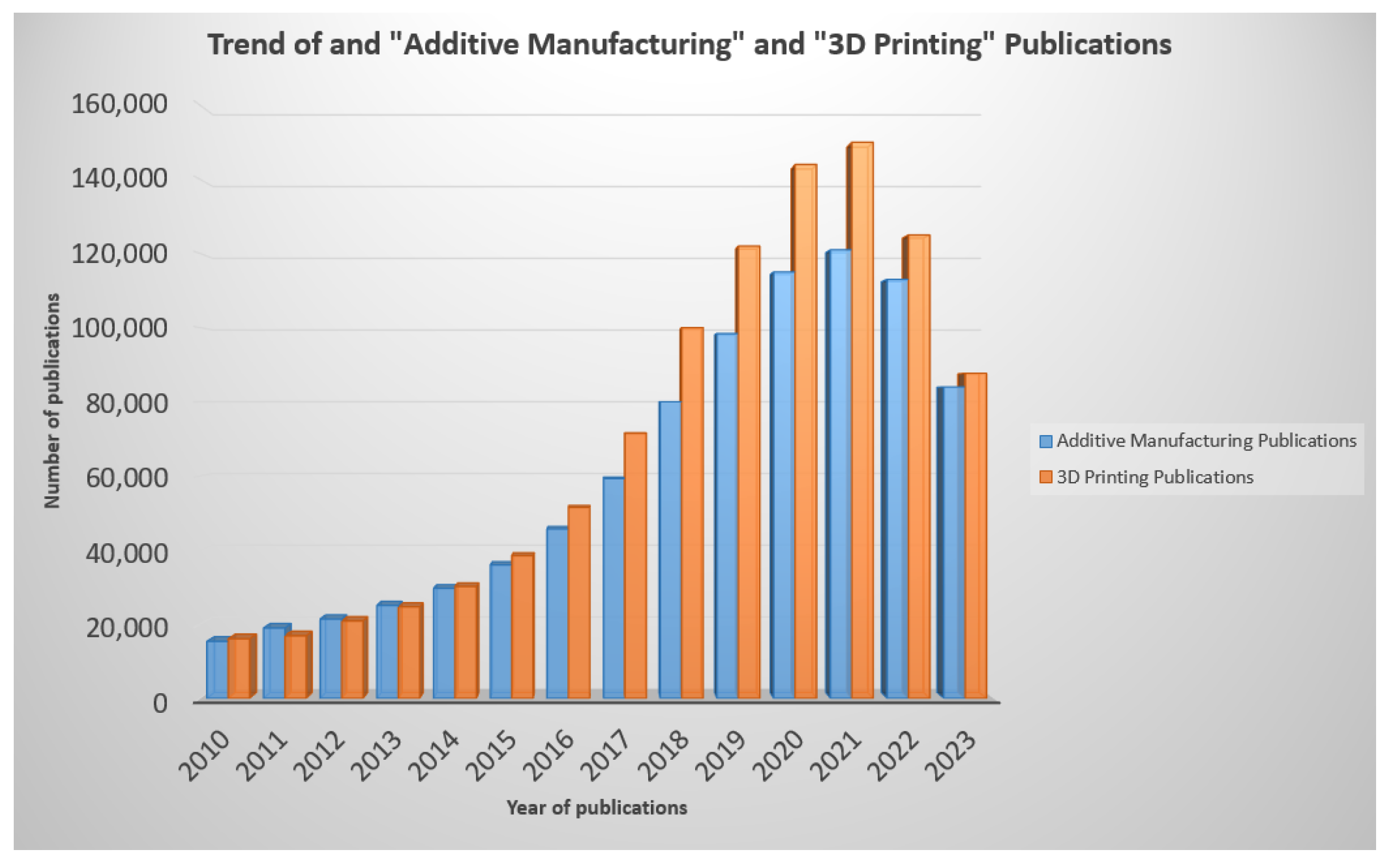

3.2. Adoption Rates and Trends

4. Advantages and Limitations

5. Applications Across Diverse Sectors

5.1. Recent Innovations

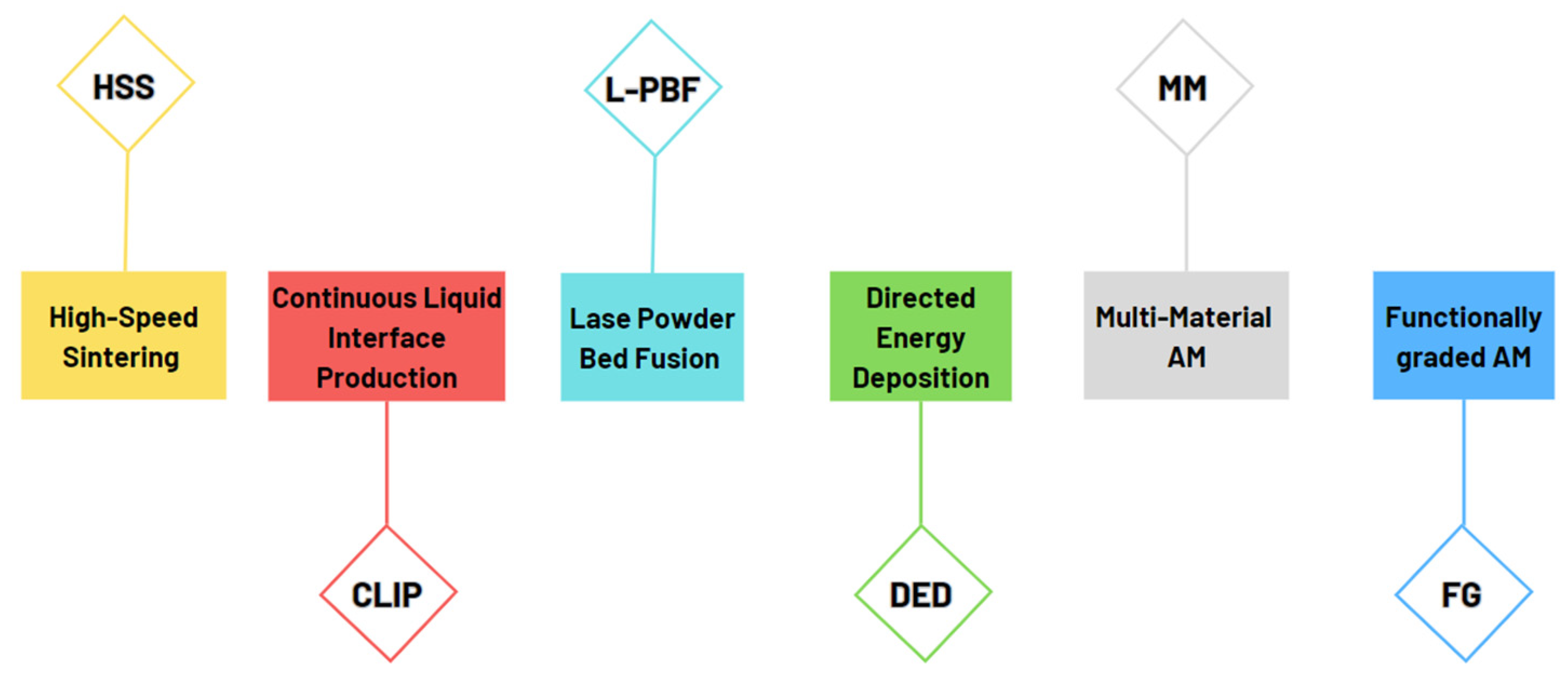

- High-speed sintering (HSS), a creation of Loughborough University, represents an innovative approach within the powder bed fusion (PBF) category, employing infrared heating to specifically sinter polymer powders. This method allows for quicker production rates and the possibility of mass-producing functional polymer parts. HSS is transforming 3D printing by making it feasible to produce complex, tailored components on a large scale affordably. Because of this, it is now a preferred method in many industries, including aerospace, the automotive industry, consumer goods, healthcare, and medicine [46,47,48];

- Advancements in laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) for additive manufacture of metals place a strong emphasis on material innovation, process control, and monitoring. These developments are intended to improve part quality, decrease porosity, improve mechanical properties, and boost production efficiency. Examples of these developments include monitoring the melt pool, using optical tomography, scanning each layer as it is deposited, applying multi-laser processing, and introducing new materials [46,50];

- Directed energy deposition (DED) methods have developed to use both powder and wire as raw materials, broadening the range of materials to metals, ceramics, and composites. This expansion increases the variety of designs that can be created and makes it easier to manufacture bigger parts. Additionally, integrating subtractive manufacturing with DED AM methods further enhances surface quality and dimensional accuracy, particularly for large components [46,51].

5.1.1. Multi-Material AM

- Conductive inks: Conductive inks containing metallic particles like silver or copper are used for printing conductive traces and interconnects;

- Dielectric and insulation inks: Dielectric inks are used to form insulating layers that are essential for separating the parts of a circuit, whereas insulating inks offer the structural support and strength needed for the printed item;

- Functional inks: Functional inks, such as magnetic or optical variants, add specific functionalities like sensors or antennas.

5.1.2. Beam-Based Metal AM

5.1.3. Stereolithography and Microwave Sintering

5.1.4. Bioprinting and Tissue Engineering

5.1.5. Two-Phonton Polymerization

5.1.6. Hybrid Technologies

5.2. Inventions in 3D Printing Technologies

5.2.1. Robotics

5.2.2. Digital Twins

5.2.3. Virtual Reality

5.2.4. Automation

5.2.5. AI-Assisted AM

5.3. New Materials

6. Current Challenges and Future Prospects

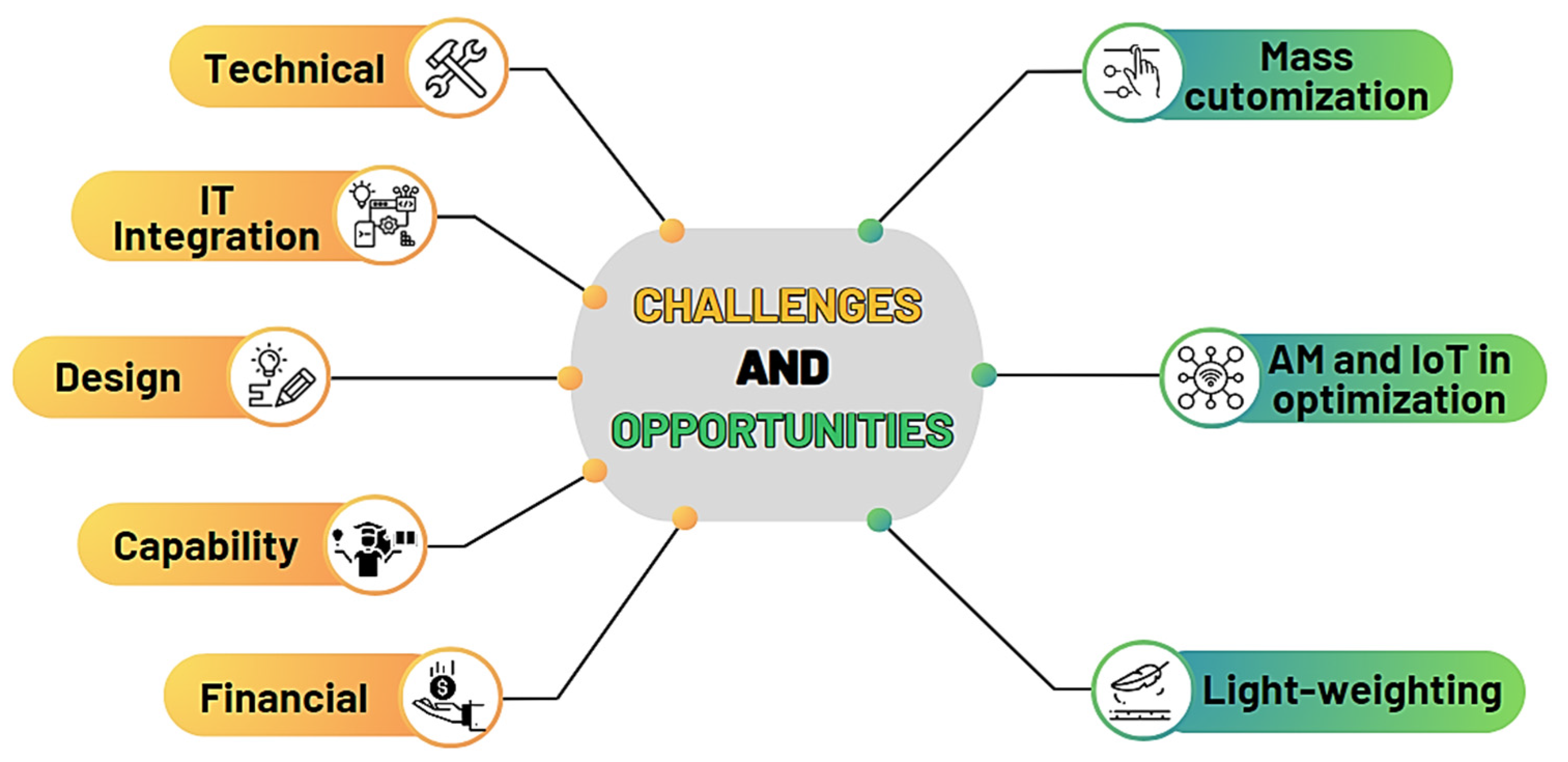

6.1. Technical and Operational Challenges

6.2. Present Obstacles Faced by AM Technologies

6.2.1. Bioprinting

6.2.2. Micro–Nano-Scale Fabrication

6.2.3. Additively Manufactured Electronics

6.2.4. Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing

6.3. Anticipated Advancements and Research Directions

6.4. Industry 5.0 as a Way to Overcome the Challenges of Industry 4.0

6.5. The Role of Additive Manufacturing in the Future Landscape of Manufacturing

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ISO/ASTM 52900; Additive Manufacturing-General Principles-Fundamentals and Vocabulary Fabrication Additive-Principes Généraux-Fondamentaux et Vocabulaire. ISO: Geneve, Switzerland, 2021.

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Heer, B. Additive manufacturing of multi-material structures. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2018, 129, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, T.S.; Xiong, G.; Shen, Z.; Leng, J.; Fang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Lodhi, E.; Wang, F.Y. 3D printing in materials manufacturing industry: A realm of Industry 4.0. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, M.; Carou, D.; Rubio, E.M.; Teti, R. Current advances in additive manufacturing. Procedia Cirp. 2020, 88, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakus, A.E. An Introduction to 3D Printing-Past, Present, and Future Promise. In 3D Printing in Orthopaedic Surgery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780323581189. [Google Scholar]

- Tofail, S.A.M.; Koumoulos, E.P.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bose, S.; O’Donoghue, L.; Charitidis, C. Additive manufacturing: Scientific and technological challenges, market uptake and opportunities. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, F.; Godina, R.; Jacinto, C.; Carvalho, H.; Ribeiro, I.; Peças, P. Additive manufacturing: Exploring the social changes and impacts. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftekar, S.F.; Aabid, A.; Amir, A.; Baig, M. Advancements and Limitations in 3D Printing Materials and Technologies: A Critical Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, H.B.; Adamiak, M.; Kunwar, A. 3D printed biomedical devices and their applications: A review on state-of-the-art technologies, existing challenges, and future perspectives. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 143, 105930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Batai, S.; Sarbassov, D. 3D printing: A critical review of current development and future prospects. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2019, 25, 1108–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, I.J.; Sevvel, P.; Gunasekaran, J. A review on the various processing parameters in FDM. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 37, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahavandi, S. Industry 5.0-a human-centric solution. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Pham, Q.V.; Prabadevi, B.; Deepa, N.; Dev, K.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Ruby, R.; Liyanage, M. Industry 5.0: A survey on enabling technologies and potential applications. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 26, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Haleem, A.; Javaid, M. Changes and improvements in Industry 5.0: A strategic approach to overcome the challenges of Industry 4.0. Green Technol. Sustain. 2023, 1, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikas, H.; Stavropoulos, P.; Chryssolouris, G. Additive manufacturing methods and modeling approaches: A critical review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 83, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadad, A.A.; Rosa-Sainz, A.; Cañete, R.; Peralta, E.; Begines, B.; Balbuena, M.; Alcudia, A.; Torres, Y. Applications and multidisciplinary perspective on 3D printing techniques: Recent developments and future trends. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2023, 156, 100760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, M.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Recent Advances in Additive Manufacturing of Engineering Thermoplastics: Challenges and Opportunities; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Volume 10, ISBN 4743160219. [Google Scholar]

- Osswald, T.A.; Baur, E.; Rudolph, N. Plastics Handbook: The Resource for Plastics Engineers; Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH Co.: Munich, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hamad, K.; Kaseem, M.; Deri, F. Recycling of waste from polymer materials: An overview of the recent works. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 2801–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Forssberg, E. Mechanical recycling of waste electric and electronic equipment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2003, 99, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos Seibert, M.; Mazzei Capote, G.A.; Gruber, M.; Volk, W.; Osswald, T.A. Manufacturing of a PET Filament from Recycled Material for Material Extrusion (MEX). Recycling 2022, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamri, A.; Lallam, A.; Harzallah, O.; Bencheikh, L. Mechanical characterization of melt spun fibers from recycled and virgin PET blends. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 8271–8278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghabezi, P.; Sam-Daliri, O.; Flanagan, T.; Walls, M.; Harrison, N.M. Circular economy innovation: A deep investigation on 3D printing of industrial waste polypropylene and carbon fibre composites. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 206, 107667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, G. 3D Printing: A Critical Element in Industry 4.0 Revolution. Think Robotics. Available online: https://thinkrobotics.com/blogs/tidbits/3d-printing-a-critical-element-in-industry-4-0-revolution (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Kantaros, A.; Ganetsos, T.; Piromalis, D. 3D and 4D Printing as Integrated Manufacturing Methods of Industry 4.0. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2023, 16, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baduge, S.K.; Thilakarathna, S.; Perera, J.S.; Arashpour, M.; Sharafi, P.; Teodosio, B.; Shringi, A.; Mendis, P. Artificial intelligence and smart vision for building and construction 4.0: Machine and deep learning methods and applications. Autom. Constr. 2022, 141, 104440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, M.S.; Bezbradica, M.; Crane, M.; Alijel, M.K. AI Cloud-Based Smart Manufacturing and 3D Printing Techniques for Future In-House Production. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Manufacturing (AIAM), Dublin, Ireland, 16–18 October 2019; pp. 747–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Roach, D.J.; Wu, J.; Hamel, C.M.; Ding, Z.; Wang, T.; Dunn, M.L.; Qi, H.J. Advances in 4D Printing: Materials and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1805290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Mangla, S.K. Evaluating challenges to Industry 4.0 initiatives for supply chain sustainability in emerging economies. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 17, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foidl, H.; Felderer, M. Research Challenges of Industry 4.0 for Quality Management; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodi, S.; Cluj-napoca, U.T.; Popescu, S.; Cluj-napoca, U.T.; Popescu, D.; Cluj-napoca, U.T. Virtual quality management elements in optimized new product virtual quality management elements in optimized new. In Proceedings of the MakeLearn and TIIM Joint International Conference 2015: Managing Intellectual Capital and Innovation for Sustainable and Inclusive Society, Bari, Italy, 27–29 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zizic, M.C.; Mladineo, M.; Gjeldum, N.; Celent, L. From Industry 4.0 towards Industry 5.0: A Review and Analysis of Paradigm Shift for the People, Organization and Technology. Energies 2022, 15, 5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General for Research and Innovation; Renda, A.; Schwaag Serger, S.; Tataj, D.; Morlet, A.; Isaksson, D.; Martins, F.; Mir Roca, M.; Hidalgo, C.; Huang, A.; et al. Industry 5.0, a Transformative Vision for Europe: Governing Systemic Transformations towards a Sustainable Industry; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 9789276433521. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, J.; Sha, W.; Lin, Z.; Jing, J.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X. Blockchained smart contract pyramid-driven multi-agent autonomous process control for resilient individualised manufacturing towards Industry 5.0. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 4302–4321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Jiang, P.; Xu, K.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, J.L.; Bian, Y.; Shi, R. Makerchain: A blockchain with chemical signature for self-organizing process in social manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 234, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Su, H.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, D. Secure Blockchain Middleware for Decentralized IIoT towards and Directions. Machines 2022, 10, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, A. Future of industry 5.0 in society: Human-centric solutions, challenges and prospective research areas. J. Cloud Comput. 2022, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, Y.; Gür, G.; Ylianttila, M.; Liyanage, M. The role of 5G for digital healthcare against COVID-19 pandemic: Opportunities and challenges. ICT Express 2021, 7, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Guo, D.; Long, F.; Mateos, L.A.; Ding, H.; Xiu, Z.; Hellman, R.B.; King, A.; Chen, S.; Zhang, C.; et al. Robots under COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 1590–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/ (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Deshmukh, K.; Talal, M.; Alali, M. Introduction to 3D and 4D Printing Technology: State of the Art and Recent Trends; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 9780128168059. [Google Scholar]

- Prashar, G.; Vasudev, H.; Bhuddhi, D. Additive manufacturing: Expanding 3D printing horizon in industry 4.0. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 17, 2221–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, M. The rise of 3-D printing: The advantages of additive manufacturing over traditional manufacturing. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R. 10 Avantaje si Dezavantaje ale Imprimarii 3D. Barrazacorlos. Available online: https://barrazacarlos.com/ro/avantaje-si-dezavantaje-ale-imprimarii-3d/ (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Vedrtnam, A.; Ghabezi, P.; Gunwant, D.; Jiang, Y.; Sam-Daliri, O.; Harrison, N.; Goggins, J.; Finnegan, W. Mechanical performance of 3D-printed continuous fibre Onyx composites for drone applications: An experimental and numerical analysis. Compos. Part C Open Access 2023, 12, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, I.; Huseynov, O.; Ali, M.A.; Alkunte, S.; Rajeshirke, M.; Gupta, A.; Hasanov, S.; Tantawi, K.; Yasa, E.; Yilmaz, O.; et al. Recent Inventions in Additive Manufacturing: Holistic Review. Inventions 2023, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, K.; Teramae, M.; Pezzotti, G. Evaluation of the Effect of High-Speed Sintering and Specimen Thickness on the Properties of 5 mol% Yttria-Stabilized Dental Zirconia Sintered Bodies. Materials 2022, 15, 5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Lu, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Xie, C.; Yu, H. Effect of high-speed sintering on the microstructure, mechanical properties and ageing resistance of stereolithographic additive-manufactured zirconia. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 9797–9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkowitz, G.; Samuelsen, T.; Hsiao, K.; Lee, B.; Dulay, M.T.; Coates, I.; Lin, H.; Pan, W.; Toth, G.; Tate, L.; et al. Injection continuous liquid interface production of 3D objects. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazia Guerra, M.; Lafirenza, M.; Errico, V.; Angelastro, A. In-process dimensional and geometrical characterization of laser-powder bed fusion lattice structures through high-resolution optical tomography. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 162, 109252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, D.G. Directed Energy Deposition (DED) Process: State of the Art; Korean Society for Precision Engineering: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021; Volume 8, ISBN 4068402000. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Lee, H. Recent advances in multi-material additive manufacturing: Methods and applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañón, L. New 3D printing Method Designed by Stanford Engineers Promises Faster Printing with Multiple Materials. Stanford News. Available online: https://news.stanford.edu/2022/09/28/new-3d-printer-promises-faster-multi-material-creations/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Shaukat, U.; Rossegger, E.; Schlögl, S. A Review of Multi-Material 3D Printing of Functional Materials via Vat Photopolymerization. Polymers 2022, 14, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R. Making Data Matter: Voxel-Printing for the Digital Fabrication of Data Across Scales and Domains. Mit Media Lab. Available online: https://www.media.mit.edu/projects/making-data-matter/overview/ (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Hasanov, S.; Gupta, A.; Nasirov, A.; Fidan, I. Mechanical characterization of functionally graded materials produced by the fused filament fabrication process. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 58, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernencu, A.; Lungu, A.; Stancu, I.C.; Vasile, E.; Iovu, H. Polysaccharide-based 3d printing inks supplemented with additives. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. B Chem. Mater. Sci. 2019, 81, 175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Persad, J.; Rocke, S. Multi-material 3D printed electronic assemblies: A review. Results Eng. 2022, 16, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R. Additive Manufacturing|TRUMPF. TRUMPF. Available online: https://www.trumpf.com/en_US/solutions/applications/additive-manufacturing/?gclid=Cj0KCQjw7PCjBhDwARIsANo7CgmvBY8WHxwX9dxzXknktMapcMU05kCW3S3XoxOEwQXiYfd3 (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Aversa, A.; Saboori, A.; Marchese, G.; Iuliano, L.; Lombardi, M.; Fino, P. Recent Progress in Beam-Based Metal Additive Manufacturing from a Materials Perspective: A Review of Patents. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2021, 30, 8689–8699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koptyug, A.; Popov, V.V.; Botero Vega, C.A.; Jiménez-Piqué, E.; Katz-Demyanetz, A.; Rännar, L.E.; Bäckström, M. Compositionally-tailored steel-based materials manufactured by electron beam melting using blended pre-alloyed powders. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 771, 138587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhdar, Y.; Tuck, C.; Binner, J.; Terry, A.; Goodridge, R. Additive manufacturing of advanced ceramic materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 116, 100736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, B.; Paulsen, S.J.; Corbett, D.C.; Sazer, D.W.; Fortin, C.L.; Zaita, A.J.; Greenfield, P.T.; Calafat, N.J.; Gounley, J.P.; Ta, A.H.; et al. Multivascular networks and functional intravascular topologies in biocompatible hydrogels. IF63.7 Sci. 2019, 464, 458–464. Available online: http://science.sciencemag.org/ (accessed on 14 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Burrows, L. Multimaterial 3D Printing with a Twist. Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Science. Available online: https://seas.harvard.edu/news/2023/01/multimaterial-3d-printing-twist (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Derakhshanfar, S.; Mbeleck, R.; Xu, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, W.; Xing, M. 3D bioprinting for biomedical devices and tissue engineering: A review of recent trends and advances. Bioact. Mater. 2018, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matai, I.; Kaur, G.; Seyedsalehi, A.; McClinton, A.; Laurencin, C.T. Progress in 3D bioprinting technology for tissue/organ regenerative engineering. Biomaterials 2020, 226, 119536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.V.; Kudryavtseva, E.V.; Katiyar, N.K.; Shishkin, A.; Stepanov, S.I.; Goel, S. Industry 4.0 and Digitalisation in Healthcare. Materials 2022, 15, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolo, P.; Malshe, A.; Ferraris, E.; Koc, B. 3D bioprinting: Materials, processes, and applications. CIRP Ann. 2022, 71, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, S.; Pandit, A.; Heise, A.; Kellett, A. Two-Photon Polymerization: Fundamentals, Materials, and Chemical Modification Strategies. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2204072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozsoy, A.; Tureyen, E.B.; Baskan, M.; Yasa, E. Microstructure and mechanical properties of hybrid additive manufactured dissimilar 17-4 PH and 316L stainless steels. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 28, 102561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pragana, J.P.M.; Sampaio, R.F.V.; Bragança, I.M.F.; Silva, C.M.A.; Martins, P.A.F. Hybrid metal additive manufacturing: A state–of–the-art review. Adv. Ind. Manuf. Eng. 2021, 2, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, V.; Fleisher, A.; Muller-Kamskii, G.; Shishkin, A.; Katz-Demyanetz, A.; Travitzky, N.; Goel, S. Novel hybrid method to additively manufacture denser graphite structures using Binder Jetting. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Ren, X.; Ma, C.; Pei, Z. Ceramic binder jetting additive manufacturing: Particle coating for increasing powder sinterability and part strength. Mater. Lett. 2019, 234, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polozov, I.; Razumov, N.; Masaylo, D.; Silin, A.; Lebedeva, Y.; Popovich, A. Fabrication of Silicon Carbide Fiber-Reinforced Silicon Carbide Matrix Composites Using Binder. Materials 2020, 13, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, A.; Zolotaryov, D.; Kovalevsky, A.; Muller-Kamskii, G.; Eshed, E.; Kazakin, M.; Popov, V.V. Reaction bonding of silicon carbides by Binder Jet 3D-Printing, phenolic resin binder impregnation and capillary liquid silicon infiltration. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 18023–18029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Tirado, A.; Conner, B.S.; Chi, M.; Elliott, A.M.; Rios, O.; Zhou, H.; Paranthaman, M.P. A novel method combining additive manufacturing and alloy infiltration for NdFeB bonded magnet fabrication. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 438, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Diller, E. Multi-material Fabrication for Magnetically Driven Miniature Soft Robots Using Stereolithography. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Manipulation, Automation and Robotics at Small Scales (MARSS), Toronto, ON, Canada, 25–29 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, G.D.; Brett, J.; O’Connor, J.; Letchford, J.; Delaney, G.W. One-Shot 3D-Printed Multimaterial Soft Robotic Jamming Grippers. Soft Robot. 2022, 9, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, N.; Bartlettj, C.W.T.; Tolleyr, J.W. Overveldek. 3D Printed Hybrid Robot. WO 2017/058334 A9. 2016. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2017058334A9/en?q=(3D+PRINTED+hybrid+robot)&oq=3D+PRINTED+hybrid+robot (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Saab, W.; Ben-Tzvi, P. A genderless coupling mechanism with six-degrees-of-freedom misalignment capability for modular self-reconfigurable robots. J. Mech. Robot. 2016, 8, 061014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulis, M.; Harvey, C. A robot arm digital twin utilising reinforcement learning. Comput. Graph. 2021, 95, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, T.; Zhang, W.; Turner, J.; Babu, S.S. Building digital twins of 3D printing machines. Scr. Mater. 2017, 135, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, T.; DebRoy, T. A digital twin for rapid qualification of 3D printed metallic components. Appl. Mater. Today 2019, 14, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, A.; Yavari, R.; Montazeri, M.; Cole, K.; Bian, L.; Rao, P. Toward the digital twin of additive manufacturing: Integrating thermal simulations, sensing, and analytics to detect process faults. IISE Trans. 2020, 52, 1204–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degraen, D.; Zenner, A.; Krüger, A. Enhancing texture perception in virtual reality using 3D-printed hair structures. In Proceedings of the CHI ‘19: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.; Hwang, J.Y.; Chung, J.; Jang, T.M.; Seo, D.G.; Gao, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, H.; Lee, S.; et al. 3D Printed, Customizable, and Multifunctional Smart Electronic Eyeglasses for Wearable Healthcare Systems and Human-Machine Interfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 21424–21432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, A.; Nasirov, A.; Fidan, I.; Allen, M.; Elliott, A.; Cossette, M.; Tackett, E.; Singer, T. Development, implementation and optimization of a mobile 3D printing platform. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 6, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Fidan, I.; Allen, M. Detection of material extrusion in-process failures via deep learning. Inventions 2020, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewe, A. Using Artificial Intelligence to Control Digital Manufacturing. MIT News Office. Available online: https://news.mit.edu/2022/artificial-intelligence-3-d-printing-0802 (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Yao, X.; Moon, S.K.; Bi, G. A hybrid machine learning approach for additive manufacturing design feature recommendation. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2017, 23, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ron, T.; Leon, A.; Popov, V.; Strokin, E.; Eliezer, D.; Shirizly, A.; Aghion, E. Synthesis of Refractory High-Entropy Alloy WTaMoNbV by Powder Bed Fusion Process Using Mixed Elemental Alloying Powder. Materials 2022, 15, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, S.; Lu, H.; Fidan, I.; Zhang, Y.; Tantawi, K.; Guo, T.; Asiabanpour, B. The Influence of Smart Manufacturing towards Energy Conservation: A Review. Technologies 2020, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.C.; Yeh, J.W.; Liaw, P.K.; Zhang, Y. (Eds.) High-Entropy Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 9783319270135. [Google Scholar]

- Eshed, E.; Larianovsky, N.; Kovalevsky, A.; Popov, V.; Gorbachev, I.; Popov, V.; Katz-Demyanetz, A. Microstructural evolution and phase formation in 2nd-generation refractory-based high entropy alloys. Materials 2018, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz-Demyanetz, A.; Gorbachev, I.I.; Eshed, E.; Popov, V.V.; Bamberger, M. High entropy Al0.5CrMoNbTa0.5 alloy: Additive manufacturing vs. casting vs. CALPHAD approval calculations. Mater. Charact. 2020, 167, 110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scime, L.; Beuth, J. A multi-scale convolutional neural network for autonomous anomaly detection and classification in a laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing process. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 24, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, M.; Niranjana, K.; Bhoopathi, R.; Rajeshkumar, L. Additive manufacturing (3D printing) technologies for fiber-reinforced polymer composite materials: A review on fabrication methods and process parameters. E-Polym. 2024, 24, 20230114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, G.; Vasudev, H. A comprehensive review on sustainable cold spray additive manufacturing: State of the art, challenges and future challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumers, M.; Dickens, P.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. Technological Forecasting & Social Change The cost of additive manufacturing: Machine productivity, economies of scale and technology-push. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2016, 102, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, M.; Loy, J.; Ghasemi, A.H.; Sharabian, E.; Leary, M.; Mirafzal, H.; Cochrane, P.; Rolfe, B.; Gibson, I. A review of Industry 4.0 and additive manufacturing synergy. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2022, 28, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare Scott Challenges and Future Trends in Additive Manufacturing. 2024. Available online: https://wohlersassociates.com/uncategorized/challenges-and-future-trends-in-additive-manufacturing/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Seth, R. 3D Printer Reversed. Available online: https://www.yankodesign.com/2014/09/12/3d-printer-reversed/ (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Lacroix, R.; Seifert, R.W.; Timonina-Farkas, A. Benefiting from additive manufacturing for mass customization across the product life cycle. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2021, 8, 100201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jambhulkar, S.; Zhu, Y.; Ravichandran, D.; Kakarla, M.; Vernon, B.; Lott, D.G.; Cornella, J.L.; Shefi, O.; Miquelard-Garnier, G.; et al. 3D printing for polymer/particle-based processing: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 223, 109102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R. The Top Challenges in Additive Manufacturing and How to Overcome Them. Dessault Systemes. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/make/solutions/blog/top-challenges-additive-manufacturing-and-how-overcome-them (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Nyamuchiwa, K.; Palad, R.; Panlican, J.; Tian, Y.; Aranas, C. Recent Progress in Hybrid Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Materials. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanov, S.; Alkunte, S.; Rajeshirke, M.; Gupta, A.; Huseynov, O.; Fidan, I.; Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Rennie, A. Review on additive manufacturing of multi-material parts: Progress and challenges. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, B. The Challenges and Opportunities of AI for Additive Manufacturing. E247 Digital Engineering. Available online: https://www.digitalengineering247.com/article/the-challenges-and-opportunities-of-ai-for-additive-manufacturing#:~:text=Artificial%20intelligence%20%28AI%29%20and%20machine%20learning%20%28ML%29%20can,about%20where%20and%20how%20to%20deploy%20the%20technology (accessed on 24 September 2024).

- Kačarević, Ž.P.; Rider, P.M.; Alkildani, S.; Retnasingh, S.; Smeets, R.; Jung, O.; Ivanišević, Z.; Barbeck, M. An introduction to 3D bioprinting: Possibilities, challenges and future aspects. Materials 2018, 11, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoni, S.; Gugliandolo, S.G.; Sponchioni, M.; Moscatelli, D.; Colosimo, B.M. 3D bioprinting: Current status and trends—A guide to the literature and industrial practice. Bio-Design Manuf. 2022, 5, 14–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.V.; Atala, A. 3D bioprinting of tissues and organs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hölzl, K.; Lin, S.; Tytgat, L.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Gu, L.; Ovsianikov, A. Bioink properties before, during and after 3D bioprinting. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, D.; Anand, S.; Naing, M.W. The arrival of commercial bioprinters—Towards 3D bioprinting revolution! Int. J. Bioprinting 2018, 4, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospodiuk, M.; Dey, M.; Sosnoski, D.; Ozbolat, I.T. The bioink: A comprehensive review on bioprintable materials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, M.; Fan, X.; Zhou, H. Recent advances in bioprinting techniques: Approaches, applications and future prospects. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbolat, I.T.; Moncal, K.K.; Gudapati, H. Evaluation of bioprinter technologies. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 13, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, S.; Lee, J.M.; Ng, W.L.; Layani, M.; Yeong, W.Y.; Magdassi, S. A novel 3D bioprinted flexible and biocompatible hydrogel bioelectronic platform. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 102, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.; Moroni, L. Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 2019: The Role of Biofabrication—A Year in Review. Tissue Eng.—Part C Methods 2020, 26, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panwar, A.; Tan, L.P. Current status of bioinks for micro-extrusion-based 3D bioprinting. Molecules 2016, 21, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, W.L.; Lee, J.M.; Zhou, M.; Chen, Y.W.; Lee, K.X.A.; Yeong, W.Y.; Shen, Y.F. Vat polymerization-based bioprinting—Process, materials, applications and regulatory challenges. Biofabrication 2020, 12, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.V.; De Coppi, P.; Atala, A. Opportunities and challenges of translational 3D bioprinting. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 4, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbolat, I.T.; Hospodiuk, M. Current advances and future perspectives in extrusion-based bioprinting. Biomaterials 2016, 76, 321–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, E.S.; Mostafa, S.; Pakvasa, M.; Luu, H.H.; Lee, M.J.; Wolf, J.M.; Ameer, G.A.; He, T.C.; Reid, R.R. 3-D bioprinting technologies in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: Current and future trends. Genes Dis. 2017, 4, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donderwinkel, I.; Van Hest, J.C.M.; Cameron, N.R. Bio-inks for 3D bioprinting: Recent advances and future prospects. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 4451–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Yang, Q.; Xu, F. Engineering bio-inks for 3D bioprinting cell mechanical microenvironment. Int. J. Bioprinting 2023, 9, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, S.; Yu, K.; Meyer, A.S.; Karana, E.; Aubin-Tam, M.E. Bioprinting of Regenerative Photosynthetic Living Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2011162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliadis, A.V.; Koukoulias, N.; Katakalos, K. From Three-Dimensional (3D)- to 6D-Printing Technology in Orthopedics: Science Fiction or Scientific Reality? J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, H.; Yang, W.; Sun, L.; Cai, S.; Yang, R.; Liang, W.; Yu, H.; Liu, L. 4D printing: A review on recent progresses. Micromachines 2020, 11, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Arya, S.; Gupta, V.; Furukawa, H.; Khosla, A. 4D printing: Fundamentals, materials, applications and challenges. Polymer 2021, 228, 123926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ramanujan, D.; Ramani, K.; Chen, Y.; Williams, C.B.; Wang, C.C.L.; Shin, Y.C.; Zhang, S.; Zavattieri, P.D. The status, challenges, and future of additive manufacturing in engineering. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2015, 69, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Significant roles of 4D printing using smart materials in the field of manufacturing. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2021, 4, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Rawat, K.; Karunakaran, C.; Rajamohan, V.; Mathew, A.T.; Koziol, K.; Kumar Thakur, V.; Balan, A.S.S. 4D printing of materials for the future: Opportunities and challenges. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 18, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xia, S.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Ren, J. Applications of four-dimensional printing in emerging directions: Review and prospects. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 91, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, E.; Loh, G.H. Technological considerations for 4D printing: An overview. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 3, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Holmukhe, R.M.; Gandhar, A.; Kumawat, K. 5D Printing: A future beyond the scope of 4D printing with application of smart materials. J. Inf. Optim. Sci. 2022, 43, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ramakrishna, S. Review of mechanisms and deformation behaviors in 4D printing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 105, 4633–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A. 4D printing applications in medical field: A brief review. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2019, 7, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani, S.; Naghib, S.M. 3D and 4D printing hydroxyapatite-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and regeneration. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farham, B.; Baltazar, L. A Review of Smart Materials in 4D Printing for Hygrothermal Rehabilitation: Innovative Insights for Sustainable Building Stock Management. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzoor, A.; Jaber, A.; Shandookh, A. 3D Printing for wind turbine blade manufacturing: A review of materials, design optimization, and challenges. Eng. Technol. J. 2024, 42, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Yang, S. Responsive Smart Windows from Nanoparticle–Polymer Composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1902597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongi, T.; Tirinato, L.; Pagliari, F.; Giugni, A.; Allione, M.; Perozziello, G.; Candeloro, P.; Di Fabrizio, E. Fabrication and Applications of Micro/Nanostructured Devices for Tissue Engineering. Nano-Micro. Lett. 2017, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; O’Brien, C.; O’Brien, J.R.; Zhang, L.G. 3D nano/microfabrication techniques and nanobiomaterials for neural tissue regeneration. Nanomedicine 2014, 9, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limongi, T.; Schipani, R.; Di Vito, A.; Giugni, A.; Francardi, M.; Torre, B.; Allione, M.; Miele, E.; Malara, N.; Alrasheed, S.; et al. Photolithography and micromolding techniques for the realization of 3D polycaprolactone scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 141, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.P.; Wachter, R.F. Challenges and opportunities in nanomanufacturing. Instrum. Metrol. Stand. Nanomanufacturing Opt. Semicond. V 2011, 8105, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G.; Kim, I.; Rho, J. Challenges in fabrication towards realization of practical metamaterials. Microelectron. Eng. 2016, 163, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Lv, Y.; Dong, C.; Sreeprased, T.S.; Tian, A.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, N. Three-dimensional micro/nanoscale architectures: Fabrication and applications. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 10883–10895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahadian, S.; Finbloom, J.A.; Mofidfar, M.; Diltemiz, S.E.; Nasrollahi, F.; Davoodi, E.; Hosseini, V.; Mylonaki, I.; Sangabathuni, S.; Montazerian, H.; et al. Micro and nanoscale technologies in oral drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 157, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, P.; Fu, Z.; Meng, S.; Dai, L.; Yang, H. Applications of nanomaterials in tissue engineering. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 19041–19058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Miccio, L.; Coppola, S.; Bianco, V.; Memmolo, P.; Tkachenko, V.; Ferraro, V.; Di Maio, E.; Maffettone, P.L.; Ferraro, P. Digital holography as metrology tool at micro-nanoscale for soft matter. Light Adv. Manuf. 2022, 3, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, K.; Song, Y.; Ahmad, Z.; Chen, X.; Chang, M.W. High Precision 3D Printing for Micro to Nano Scale Biomedical and Electronic Devices. Micromachines 2022, 13, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, G.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, H. Bioinspired Functional Surfaces for Medical Devices. Chinese J. Mech. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 35, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, J.; Das, P.; Zheng, S.; Wu, Z.S. Recent status and future perspectives of 2D MXene for micro-supercapacitors and micro-batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 51, 500–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakaran, N.; Das, J.P.; PV, A.K.; Mohanty, S.; Ramadoss, A.; Nayak, S.K. Comprehensive review on various additive manufacturing techniques and its implementation in electronic devices. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 62, 477–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efstratiadis, V.S.; Michailidis, N. Sustainable Recovery, Recycle of Critical Metals and Rare Earth Elements from Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment (Circuits, Solar, Wind) and Their Reusability in Additive Manufacturing Applications: A Review. Metals 2022, 12, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailkhura, G.; Mandel, R.K.; Shooshtari, A.; Ohadi, M. Numerical and Experimental Study of a Novel Additively Manufactured Metal-Polymer Composite Heat-Exchanger for Liquid Cooling Electronics. Energies 2022, 15, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, L. Additive Manufacturing of Cooling Systems Used in Power Electronics. A Brief Survey. In Proceedings of the 2022 29th International Workshop on Electric Drives: Advances in Power Electronics for Electric Drives (IWED), Moscow, Russia, 26–29 January 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espera, A.H.; Dizon, J.R.C.; Valino, A.D.; Advincula, R.C. Advancing flexible electronics and additive manufacturing. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2022, 61, SE0803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alteneiji, M.; Ali, M.I.H.; Khan, K.A.; Al-Rub, R.K.A. Heat transfer effectiveness characteristics maps for additively manufactured TPMS compact heat exchangers. Energy Storage Sav. 2022, 1, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, L.; Deng, G.; Deng, C.; Bai, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Recent progress on additive manufacturing of multi-material structures with laser powder bed fusion. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2022, 17, 329–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.H.; Avinash, K.; Varaprasad, B.K.S.V.L.; Goel, S. A Review on Printed Electronics with Digital 3D Printing: Fabrication Techniques, Materials, Challenges and Future Opportunities. J. Electron. Mater. 2022, 51, 2747–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, H.; Su, J.; Tian, Y.; Wen, S.; Su, B.; Yang, C.; Chen, B.; Zhou, K.; Yan, C.; et al. Recent Advances on High-Performance Polyaryletherketone Materials for Additive Manufacturing. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2200750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Wu, L.; Gu, D.; Yuan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Ouyang, L.; Song, B.; Gao, T.; He, J.; et al. Roadmap for Additive Manufacturing: Toward Intellectualization and Industrialization. Chinese J. Mech. Eng. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2022, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Polden, J.; Li, Y.; He, F.; Xia, C.; Pan, Z. Layer-by-layer model-based adaptive control for wire arc additive manufacturing of thin-wall structures. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33, 1165–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Wang, D.; Hu, W.; Di, X.; Zhang, J. In-situ heat treatment (IHT) wire arc additive manufacturing of Inconel625-HSLA steel functionally graded material. Mater. Lett. 2023, 330, 133326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.; Pragana, J.P.M.; Ferreira, B.; Ribeiro, I.; Silva, C.M.A. Economic and Environmental Potential of Wire-Arc Additive Manufacturing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Su, C.; Zhu, J. Comprehensive review of wire arc additive manufacturing: Hardware system, physical process, monitoring, property characterization, application and future prospects. Results Eng. 2022, 13, 100330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalkar, R.; Dubey, H.K.; Lokhande, S.P. Wire arc additive manufacturing: A brief review on advancements in addressing industrial challenges incurred with processing metallic alloys. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 50, 1971–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclean, N.; Bermingham, M.J.; Colegrove, P.; Sales, A.; Dargusch, M.S. Understanding the grain refinement mechanisms in aluminium 2319 alloy produced by wire arc additive manufacturing. Sci. Technol. Weld. Join. 2022, 27, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, A.A.; Santos, A.T.G.; Bevans, B.B.; Smoqi, Z.B.; Rao, P.B. Effect of contaminations on the acoustic emissions 1 during wire and arc additive manufacturing of 316L 2 stainless steel. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 51, 102585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.A.; Bairrão, N.; Farias, F.W.C.; Shamsolhodaei, A.; Shen, J.; Zhou, N.; Maawad, E.; Schell, N.; Santos, T.G.; Oliveira, J.P. Steel-copper functionally graded material produced by twin-wire and arc additive manufacturing (T-WAAM). Mater. Des. 2022, 213, 110270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Dallasega, P.; Orzes, G.; Sarkis, J. Industry 4.0 technologies assessment: A sustainability perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 229, 107776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M. Industry 4.0, digitization, and opportunities for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, S.; Ambad, P.; Bhosle, S. Industry 4.0—A Glimpse. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 20, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiel, D.; Müller, J.M.; Arnold, C.; Voigt, K.I. Sustainable Industrial Value Creation: Benefits and Challenges of Industry 4.0. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2017, 21, 1740015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervural, B.C.; Ervural, B. Overview of Cyber Security in the Industry 4.0 Era; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, S.; Cang, S.; Yu, H.; Li, Y. Management approaches for Industry 4.0: A human resource management perspective. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–29 July 2016; pp. 5309–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadge, A.; Er Kara, M.; Moradlou, H.; Goswami, M. The impact of Industry 4.0 implementation on supply chains. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 31, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterrieder, P.; Budde, L.; Friedli, T. The smart factory as a key construct of industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.T.R.; Luo, H.; Huang, G.Q.; Yang, X. Industrial wearable system: The human-centric empowering technology in Industry 4.0. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 2853–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Ul Haq, M.I.; Raina, A.; Suman, R. Industry 5.0: Potential applications in covid-19. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2020, 5, 507–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Vogel-Heuser, B.; Wang, L. Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0—Inception, conception and perception. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J. Enabling Technologies for Industry 5.0: Results of a Workshop with Europe’s Technology Leaders; EU Publications: Luxembourg, 2020; p. 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, K.A.; Döven, G.; Sezen, B. Industry 5.0 and Human-Robot Co-working. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 158, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja Santhi, A.; Muthuswamy, P. Industry 5.0 or industry 4.0S? Introduction to industry 4.0 and a peek into the prospective industry 5.0 technologies. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 17, 947–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, S.; Abbasi, S.; Faramarzi, S.; Kiani, S.; Yazdani, A. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked Investigating the role of machine learning techniques in internet of things during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Informatics Med. Unlocked 2024, 45, 101453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, A.H.M.; Shaari, N.; Attar Bashi, Z.S.; Iftikhar, S.; Bawazeer, S.; Osman, S.H.; Hasan, N.S. A review of residential blockchain internet of things energy systems: Resources, storage and challenges. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 1225–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaife, A.D. Improve predictive maintenance through the application of artificial intelligence: A systematic review. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, B.J. Artificial Intelligence (AI)|Definition, Examples, Types, Applications, Companies, & Facts|Britannica. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/technology/artificial-intelligence (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Ranger, S. What Is Cloud Computing? Everything You Need to Know about the Cloud Explained. ZDNET. Available online: https://www.zdnet.com/article/what-is-cloud-computing-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-cloud/ (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Tissir, N.; El Kafhali, S.; Aboutabit, N. Cybersecurity management in cloud computing: Semantic literature review and conceptual framework proposal. J. Reliab. Intell. Environ. 2021, 7, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monostori, L. Cyber-physical production systems: Roots, expectations and R&D challenges. Procedia CIRP 2014, 17, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanislav, T.; Miclea, L. Cyber-physical systems—Concept, challenges and research areas. Control Eng. Appl. Inform. 2012, 14, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mourtzis, D.; Zogopoulos, V.; Xanthi, F. Augmented reality application to support the assembly of highly customized products and to adapt to production re-scheduling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 105, 3899–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, M.; Stjepandic, J.; Stobrawa, S.; Von Soden, M. Improvement of factory planning by automated generation of a digital twin. Adv. Transdiscipl. Eng. 2020, 12, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, J.M.; Fisk, A.D.; Rogers, W.A. Toward a Framework for Levels of Robot Autonomy in Human-Robot Interaction. J. Hum. -Robot. Interact. 2014, 3, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederico, G.F. From Supply Chain 4.0 to Supply Chain 5.0: Findings from a Systematic Literature Review and Research Directions. Logistics 2021, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, J.; Markusen, J.R. Additive Manufacturing in Industrial Applications. Xometry-Where Big Ideas Are Built. 2016, pp. 1–23. Available online: https://xometry.pro/en-tr/articles/additive-manufacturing-industrial-applications/ (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Sanchez, M.; Exposito, E.; Aguilar, J. Autonomic computing in manufacturing process coordination in industry 4.0 context. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2020, 19, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, S.; Lv, J.; Peng, T.; Waqar, S.; Yin, E. A big data-driven framework for sustainable and smart additive manufacturing. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M. Additive manufacturing applications in industry 4.0: A review. J. Ind. Integr. Manag. 2019, 4, 1930001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Agustín, F.; Ruiz-Salgado, S.; Zenteno-Mateo, B.; Rubio, E.; Morales, M.A. 3D pattern formation from coupled Cahn-Hilliard and Swift-Hohenberg equations: Morphological phases transitions of polymers, bock and diblock copolymers. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 210, 111431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandyal, A.; Chaturvedi, I.; Wazir, I.; Raina, A.; Ul Haq, M.I. 3D printing—A review of processes, materials and applications in industry 4.0. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Process | Definition According to ASTM 52900:2021 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Binder jetting (BJT) | Process in which a liquid bonding agent is selectively deposited to join powder materials. |

| 2. | Direct energy deposition (DED) | Process in which focused thermal energy is used to fuse materials by melting as they are being deposited. |

| 3. | Material extrusion (MEX) | Process in which material is selectively dispensed through a nozzle or orifice. |

| 4. | Material jetting (MJT) | Process in which droplets of feedstock material are selectively deposited. |

| 5. | Powder bed fusion (PBF) | Process in which thermal energy selectively fuses regions of a powder bed. |

| 6. | Sheet lamination (SHL) | Process in which sheets of material are bonded to form a part. |

| 7. | Vat photopolymerization (VPP) | Process in which liquid photopolymer in a vat is selectively cured by light-activated polymerization. |

| AM Advantages |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AM Disadvantages |

|

| No | Advantage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Exceptional speed | CLIP prints are just as precise and smooth as DLP/SLA prints but can finish printing up to 100 times quicker. |

| 2. | Superior surface finish | The lack of visible layers in CLIP prints improves their surface quality, making them comparable to parts made by injection molding. |

| 3. | Exceptional properties | CLIP-printed parts are waterproof, have uniform properties in all directions, and are stronger than those printed with SLA/DLP. |

| 4. | Versatility for prototyping and production | CLIP is appropriate for both creating functional prototypes and conducting entire production cycles. |

| 5. | Structural integrity | CLIP can seamlessly incorporate different cellular structures within a single component to provide varied performance traits. |

| 6. | Versatility | Printers using CLIP/DLS technology support a wide variety of materials, setting them apart from many other types of printers. |

| Material | Picture | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| ESD |  | ESD Fiberlogy filament protects sensitive electronic components from electrostatic discharges, reducing the risk of damage. |

| CPE ANTIBAC |  | This innovative antibacterial filament boasts high mechanical strength, temperature resistance, and antimicrobial properties, making it ideal for various applications. |

| PCTG |  | PCTG filament, a variant of PET-G, offers enhanced impact strength, temperature resistance, and clarity without needing a heated chamber. Its low shrinkage ensures high dimensional stability, making it ideal for novice 3D printing enthusiasts. |

| CPE HT |  | CPE HT filament, a modern copolyester, stands out for its high mechanical and temperature resistance. Unlike its counterparts like PETG and PCTG filaments, it excels in withstanding high temperatures, reaching up to 110 °C. Additionally, it exhibits ongoing high resistance to chemicals and lipids. |

| FIBERFLEX |  | Flexible-filament 3D-printed items have the following characteristics: excellent resistance to chemicals and abrasions, low temperature resistance, and high impact resistance. |

| FIBERSATIN |  | FiberSatin filament offers a solution to the visible layer boundaries common in 3D printing, providing a high layer bondability and a semi-matte finish that gives models a refined appearance. It serves as an alternative to silk filaments, offering a distinctive matte finish with a touch of glossiness. |

| FIBERSILK |  | FiberSilk filament produces 3D printouts with a distinctive metallic shine, highlighting intricate details and enhancing aesthetic appeal. It has a low visibility of layer boundaries and high impact strength. |

| FIBERSMOOTH |  | FiberSmooth, a type of PVB filament, offers easy post-processing by smoothing it with isopropyl alcohol (IPA). This process partially dissolves the model, improving layer adhesion and hiding layer boundaries, leading to a glossy, porcelain-like surface. |

| FIBERWOOD |  | Available for over a decade, it combines wood particles with resin, creating beautiful prints that smell like real wood. |

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Internet of Things (IoT) | IoT links computing power and network connections to sensors and objects, using different ways of communication such as between devices or from a device to a gateway. To fully tap into what IoT can do, it is important to deal with issues related to security and privacy [186,187]. |

| Artificial intelligence (AI) | Artificial intelligence is about computers copying smart actions with minimal help from humans, commonly seen as the science of making machines that can decide things on their own without people telling them what to do [188,189]. |

| Cloud computing | Cloud computing is a new technology that can save industries from managing their own computer hardware. By sharing resources virtually, clouds can serve many users with different needs using a single set of physical resources. This can save costs and offer an alternative to owning hardware for both industries and scientists [190,191]. |

| Cyber–physical systems | Cyber–physical systems (CPSs) are a new kind of system that combine computing with physical actions, creating new ways for people to interact with them. By leveraging computation and communication, CPSs extend the capabilities of the physical world, emphasizing the significance of communication and control in driving future technological progress [192,193]. |

| Augmented reality | Augmented reality (AR) merges virtual and real environments by enriching real-world objects with computer-generated information or objects through various technologies. By harnessing human capabilities, AR offers effective and complementary tools to aid in manufacturing tasks [172,194]. |

| Simulation | Simulation serves as a potent tool for decision-making. As digitalization advances, simulation methods become more relevant, offering comprehensive, efficient, embedded, and cost-effective solutions [195]. |

| Autonomus robots | Autonomous robots have the capability to identify issues and adapt their tasks independently to maintain smooth operation of processes. However, the level of a robot’s independence, from being controlled by humans to operating entirely on its own, influences how humans and robots interact [196]. |

| Concept | Definition |

|---|---|

| Customization and personalization | 3D printing allows for the creation of products that are highly customized and personalized, fitting the specific needs and likes of individuals. This fits well with the people-focused approach of Industry 5.0, making it possible to produce unique items that more closely match consumers’ expectations. |

| Agile production | Unlike traditional manufacturing methods, which often require expensive tooling and long lead times for production setup, 3D printing offers greater agility. It enables businesses to quickly adapt to shifting customer needs and market demands by facilitating on-demand manufacturing and rapid prototyping. |

| Complex geometry | Complex forms and intricate structures that may not be possible to create using conventional manufacturing techniques can now be produced thanks to additive manufacturing technology. This opens up new options for design and makes it possible to make components that are light but still have good performance. |

| Sustainability | 3D printing could cut down on material waste by using only what is necessary for making a product, thus reducing unused materials and excess stock. Moreover, by allowing for manufacturing to happen locally, 3D printing could lessen the environmental toll of transport and logistics. |

| Supply chain resilience | Industry 5.0 emphasizes resilience in supply chains, and 3D printing can contribute to this by decentralizing production and reducing reliance on centralized manufacturing facilities. By producing parts and products closer to the point of consumption, companies can mitigate risks associated with disruptions in global supply chains. |

| Design integration | 3D printing technologies are increasingly being integrated with digital design and manufacturing platforms, enabling seamless collaboration between digital design tools, simulation software, and additive manufacturing hardware. This digital integration enhances efficiency, accuracy, and quality in the manufacturing process. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bănică, C.-F.; Sover, A.; Anghel, D.-C. Printing the Future Layer by Layer: A Comprehensive Exploration of Additive Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9919. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14219919

Bănică C-F, Sover A, Anghel D-C. Printing the Future Layer by Layer: A Comprehensive Exploration of Additive Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 4.0. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(21):9919. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14219919

Chicago/Turabian StyleBănică, Cristina-Florena, Alexandru Sover, and Daniel-Constantin Anghel. 2024. "Printing the Future Layer by Layer: A Comprehensive Exploration of Additive Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 4.0" Applied Sciences 14, no. 21: 9919. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14219919

APA StyleBănică, C.-F., Sover, A., & Anghel, D.-C. (2024). Printing the Future Layer by Layer: A Comprehensive Exploration of Additive Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 4.0. Applied Sciences, 14(21), 9919. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14219919