Abstract

Wine quality and safety is affected by the food contact materials (FCMs) used. These materials are expected to protect the beverage from any chemical, physical, or biological hazard and preserve its composition stable throughout its shelf-life. However, the migration of chemical substances from FCMs is a known phenomenon and requires monitoring. This review distinguishes the migrating chemical substances to those of (i) industrial origin with potential safety effects and those of (ii) natural occurrence, principally in cork (ex. tannins) with organoleptic quality effects. The review focuses on the migration of industrial chemical contaminants. Migration testing has been applied only for cork stoppers and tops, while other materials like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles with aluminum cups, paperboard cartons, stainless steel vats, and oak casks have been examined for the presence of chemical migrating substances only by wine analysis without migration testing. The dominant analytical techniques applied are gas and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (MS) for the determination of organic compounds and Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and ICP-MS for elemental analysis. Targeted approaches are mostly applied, while limited non-target methodologies are reported. The identified migrating substances include authorized substances like phthalate plasticizers, monomers (bisphenol A), antioxidants (Irganox 1010), known but non-authorized substances (butylparaben), break-down products, oxidation products (nonylphenol), polyurethane adhesive by-products, oligomers, ink photoinitiators, and inorganic elements. A preliminary investigation of microplastics’ migration has also been reported. It is proposed that further research on the development of comprehensive workflows of target, suspect, and non-target analysis is required to shed more light on the chemical world of migration for the implementation of an efficient risk assessment and management of wine contact materials.

1. Introduction

Wine is an appreciated constituent in adults’ diets due to its organoleptic properties and its health-promoting and disease-preventing effects [1,2]. Moderate wine consumption, particularly red wine, has been related to anti-inflammation, promoting healthy aging, and prevention of cardiovascular diseases, cancers, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [1,2]. The wine industry possesses a significant place in the global economy, with an estimated world wine consumption of 232 mhl in 2022 and global wine exports in the same year amounting to 107 mhl [3].

From its production to its transportation, storage, and finally, consumption, wine comes into contact with several materials and articles, such as various types of containers, pipes, packaging, and serving glassware. During the contact of wine with all these materials, substances present in or on the material may be transferred to wine [4]. To start with, the occurrence of these substances that have migrated into wine may endanger its safety if they concern substances at concentrations with adverse effects on human health after dietary exposure [5]. Secondly, their occurrence may downgrade wine quality in terms of organoleptic characteristics and provoke a change in wine composition [6,7]. Therefore, analytical methods are required for quality and safety control of wine products in terms of wine contact materials.

This review studies published research on the migration of chemical substances from wine contact materials to wine. It is shown that these substances can be divided into two groups based on their origin (industrial use or natural occurrence) and their relation to the safety and organoleptic quality of wine. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a review deals with the chemical migration to wine in a holistic way, including all kinds of chemical substances. Subsequently, the review focuses especially on the migration of chemical contaminants used in the manufacture of food contact materials (FCMs), and the analytical methodologies applied for their determination are presented. Finally, existing gaps in the scientific field of chemical migration from food contact materials to wine are highlighted, and new perspectives are presented.

2. Wine Packaging Materials

Food packaging serves several roles, the most important of which is the protection and preservation of the quality of the food or beverage content. It is anticipated to protect the beverage from any chemical, physical, or biological hazard and preserve its composition to be stable throughout its shelf-life. Food packaging has been evolving for thousands of years. From ancient amphoras dating back to 1500BC [8] to modern active packaging containers [9] and composite paper bottles, wine packaging has come a long way. Glass and cork are still regarded as the most commonly used packaging materials; however, alternative packaging solutions such as lightweight glass, bag-in-box packaging systems, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles, aseptic cartons, and aluminum cans are now sought after.

Glass is considered the oldest and most traditional wine container. The popularity of glass lies mainly in its physical and chemical properties but also in its added value on consumer-perceived wine quality [10]. Among other advantages, glass forms a barrier against vapors and gases; it is odorless and chemically inert, can be manufactured in various formats, and can protect wine from UV radiation if treated properly.

Wine in glass bottles has been traditionally sealed with natural cork (Quercus Suber L.) stoppers. In order to meet increasing stakeholder requirements in both economic and environmental aspects, agglomerated closure solutions have been employed. The latter closures are comprised of cork granules with typically 2–5% of binding factors, including phthalates and adipates [11]. Cork-based closures undergo a surface treatment with food-grade paraffin and silicone to improve barrier properties and facilitate insertion and removal of the cork [4]. Apart from natural cork-based closures, other materials are also currently employed. These include closures made of aluminum and PET, tin, and plastic, mainly Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) with limited quantities of High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) or Polypropylene (PP) [12,13]. Plastic closures are designed to look like natural cork and are produced as compressed plastic. For that reason, they are much cheaper than natural cork. Unfortunately, this type of closure consists of a non-biodegradable material [14]. The polymers that are usually used for food are LDPE for co-extruded stoppers and styrene–butadiene–styrene (SBS) or styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) for molded ones [15].

Although glass presents significant advantages for bottling wine, the increased energy requirements associated with glass production, the high transportation costs related to its heavy weight despite the adoption of lightweight glass, and the glass’s susceptibility to breakage constitute its major drawbacks [16]. The latter has given rise to the increasing adoption of alternative wine packaging.

One of these alternatives concerns bag-in-box systems, which appeared as a packaging alternative in the food industry in the late 50s and were first adopted for packaging wine in bulk around the 1970s. This type of container enabled wine packaging in larger formats, facilitated transport and stockage, and significantly contributed to the lowering of wine production’s carbon footprint [17]. Bag-in-box systems consist of a flexible, welded composite “bag” equipped with a polypropylene valve fitting for pouring the wine and an outer rectangular paperboard “box” serving for mechanical protection. The inner layer of the bag is mainly produced from either ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) or LDPE [18]. The outer layer, which can vary in composition with aluminum, polyethylene, polyamide, or linear LDPE being the most commonly used materials, serves as the high barrier layer [19]. The FCMs are commonly polyethylene or linear LDPE [19]. The packaging procedure consists of pre-evacuation of air through a vacuum, filling the bag with wine, and inert gas addition to remove the remaining headspace oxygen. As the container is emptied, the bag collapses, protecting the wine from oxygen. Boxed wine can be found in various formats, commonly ranging from 3 to 20 L, with 3L and 5L containers considered to be the most popular ones.

Over the last decades, PET packaging materials have been extensively used for beverages, including wine, as an alternative to glass. PET is produced through a series of reactions, including ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid, which result in the formation of a condensation polymer [20]. The polymer is then transformed into easily moldable PET small pellets and then into bottles through various processes, including extrusion, heating, and cooling [21]. PET bottles present various advantages, including shatter resistance, chemical resistance, flexibility, lightweight, low production and transport cost, and recyclability. Their permeability to light, gases, vapors, and low molecular weight molecules can be improved [22]. The main approaches, in sole or in combination, to improve the gas barrier properties of PET bottles are considered to be the use of coatings, additional layers, blending [23], or the employment of active oxygen scavengers [9,23]. Closures employed in wine packaging in PET bottles can include a variety of options, such as aluminum, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), PET, LDPE, HDPE, and tin capsules [19]. Lately, PET bottles have been subjected to a renaissance with the application of modern packaging approaches. As a result, nowadays, PET bottles can be found in the market in various shapes, from classic round to flat bottles, made of either virgin or recycled material [24]. The impact of recycled PET bottles on wine’s aroma profile [25] and on sustainability with regard to greenhouse gas emissions have been investigated [26].

Aseptic cartons are multilayer composite packaging solutions [27]. The traditional representative of this category, TetraPak®, comprises 70–75% paperboard (cellulose), 20–25% LDPE, and 5% aluminum foil layers [28,29]. Paperboard is used for its mechanical properties, which provide stability and a smooth printing surface. LDPE serves as a barrier against moisture and helps the paperboard to stick to the aluminum foil [28]. The aluminum foil forms a barrier against oxygen and light, protecting wine from oxidation. Lately, other paper-based packaging systems have been proposed under the collective term paper bottles [30]. For example, in 2020, Cantina Goccia was the first winery to adopt Frugalpac®’s Frugal paper bottle packaging approach [31]. The Frugal Bottle comprises of an outer recycled paperboard shell and an inner pouch. It is claimed that Frugal bottles are five times lighter than normal glass bottles, present a considerably lower carbon footprint than conventional glass bottles, and demand significantly less plastic for their production in comparison to plastic bottles [31].

Another material used in wine packaging is cans. Wine packaged in cans is a practice initially adopted during World War One and afterward found commercial applications in the mid-1930s [32]. Commonly, the cans are made of aluminum alloys, an easily available, durable, environmentally sustainable metal that features increased barrier properties and is lightweight [33]. Nonetheless, aluminum is not inert [34]. When exposed to oxygen, it quickly forms a thin layer of aluminum oxide, which acts as a protective barrier; however, the remaining exposed aluminum is prone to corrosion in acidic media such as wine. As a solution, inner linings are employed to prevent the aluminum–wine interaction and its migration to the matrix. It should be noted that the linings often contain Bisphenol A (BPA), a substance prone to migration that presents endocrine- and reprotoxic-disrupting properties [35,36]. Despite increasing market shares, the canned wine industry has faced product quality issues owing to aluminum haze formation [33] as well as sensorial degradation related to the formation of reductive sulfur-based off-odors after a reaction between aluminum and sulfur dioxide [37].

3. Chemical Migration, European Regulation, and International Organization of Vine and Wine

Migration of chemical substances is a diffusion process subject to both kinetic and thermodynamic control. The parameters that affect the phenomenon of migration are related to (i) the type of FCM, (ii) the food/beverage content, and (iii) the conditions (time and temperature) of contact [38].

In more detail, the migration of chemical substances depends on the composition of the FCM, which is the source of the migrating compounds. The identity and concentration of these compounds present affect their migration into the food/beverage. In addition, the type of FCM is crucial in terms of thickness, permeability, porosity, degree of crystallinity, and number and type of layers that it consists of, affecting the diffusion of chemicals in the material [38]. In impermeable materials like metals, glass, and ceramics, in the absence of another type of chemical interaction, migration can occur only from the contact surface and not from the interior of the material [38]. On the contrary, permeable materials like rubbers, elastomers, and soft and flexible plastics exhibit limited resistance to mass transfer from their interior. In addition to this, porous materials like paper and board, which consist of open networks of fibers, may permit the transfer of chemical compounds of low molecular weight [38].

The nature of the food (aqueous, acidic, alcoholic, etc.) defines whether there will be an interaction with the contact material and eventually affects the migration that will occur. For example, the interaction between an uncoated metal surface and an acidic beverage like wine could lead to corrosion of the surface and the release of metal into the beverage. Finally, the conditions of contact include the contact surface/food mass ratio, temperature, and duration [38,39].

The safety of all types of materials and articles intended to come into contact with food is secured by the Framework Regulation (EC) 1935/2004 [40], according to which the manufacturing of these materials and articles should be compliant with good manufacturing practice, ensuring that under typical and predictable conditions they do not transfer any constituents to food in quantities that might endanger human health or cause unacceptable changes in the composition of the food, or cause deterioration in the organoleptic characteristics of the food.

Specifically, the use of plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food is further regulated according to Commission Regulation (EU) No. 10/2011 [41]. On the one hand, the compliance of materials and articles not yet in contact with food is demonstrated by migration testing under specific conditions of food simulant, time, and temperature. By definition, in the EU, the alcohol content of wine is generally between 8.5% (v/v) and 15% (v/v), while in specific cases, it can be as low as 4.5% (v/v) or as high as 20% (v/v) [42]. Liqueur wines (fortified wines) and aromatized wines can reach an alcohol content of up to 22% (v/v) [42,43]. Based on the alcohol content, the food simulant that is assigned to be used during the migration test by the Regulation is ethanol 20% (v/v) for wines and ethanol 50% (v/v) for liqueur wines and wine-based products with an alcohol content above 20%. In addition, the pH values of wine can range between 2.9 and 3.8 [44]. Therefore, based on these pH values, the food simulant that is assigned for the migration test is acetic acid 3% (w/v). The extract of the food simulant is analyzed using appropriate analytical methods. On the other hand, for materials and articles already in contact with food, the testing includes analysis of the food that has been treated according to the instructions of the packaging, homogenized, and analyzed with appropriate analytical methods. The analytical method to be applied depends on the compounds that are investigated.

But which substances can possibly migrate? Based on the current legislation and literature, these can be divided into Intentionally Added Substances (IAS) and Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIAS) [40,41,45]. The term IAS refers to substances that are intentionally used in the manufacture of plastics intended to come into contact with food and may include monomers, additives, colorants, and antioxidants, among others. Reg EU 10/2011 lists more than 1000 such authorized substances and defines the Specific Migration Limit (SML) for more than 400 of them, expressed in mg of substance per kg of food or food simulant (mg/kg). These compounds can be determined using sensitive analytical methods with limits of quantification that comply with the SMLs. However, an analytical challenge is that only ca. 60% of these regulated substances have an available analytical standard, which is necessary for the reliable identification and quantification of the compounds [46,47].

On the other hand, the term NIAS refers to substances that are not added for a technical reason during the production process but are present in food contact materials (FCMs) and could, therefore, migrate into food. These substances could be (i) break-down products originating from the degradation of polymers and additives, (ii) impurities present in raw materials used during the manufacture of plastics, (iii) reaction by-products generated during the production of the plastics, such as oligomers of PET during the polymerization process [48,49,50], and finally, (iv) contaminants that can originate from the recycled material’s input and recycling process, the previously packaged food, and/or misuse of the packaging before recycling [45,51]. It is apparent that the analytical determination of NIAS requires wide-scope analytical methods of high-confidence structural identification since the analytes might be unknown.

It is noted that according to Reg EU 10/2011, there are substances that are not allowed to migrate at all into food, like some primary aromatic amines. For some of these substances, there are specific requirements for the detection limit of the applied analytical method, whereas, in the absence of specific detection limits, a general limit of 0.01 mg/kg is required. The same regulation also defines that the overall migration (OM) limit, which is the maximum permitted amount of non-volatile substances released from a material or article into food simulants, should not exceed the value of 10 mg/dm2 or 60 mg/kg.

The use of recycled plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with foods is specified according to Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1616 [52], where it is defined that the recycled plastic should be in compliance with Commission Regulation (EU) No 10/2011 and that the sum of constituents of the plastic material, which occur due to repeated recycling, like for example residues of additives, should be considered as non-intentionally added substances and their concentrations should remain at levels that are considered safe according to a risk assessment [41,52].

The migration of substances from glass is specified in Council Directive 84/500/EEC [53] and Commission Directive 2005/31/EC [54] related to ceramic articles intended to come into contact with foodstuffs, which define the specific migration limits for lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) at 4.0 mg/L and 0.3 mg/L, respectively, the conditions of the migration test using a food simulant 4% (v/v) acetic acid, and the performance criteria of the analytical method (limits of detection and quantification, recovery, and specification). At this point, it should be noted that Pb and Cd could be found in food, especially in wine, from other sources since these elements are environmental pollutants. The specific migration limits concern only the migration from ceramic materials and are different from the maximum levels permitted to be found in foodstuffs specified in Reg EU 2023/915 [55]. In particular, the maximum level of lead in wine and wine-based products ranges between 0.10 and 0.20 mg/kg, while no respective maximum level is set for cadmium in wine. Regarding the latter, the International Organization for Vine and Wine (OIV) has set a maximum acceptable limit of 0.01 mg per L of wine [56]. Finally, Pb and Cd should not be detected after migration testing of plastic material, according to Reg 10/2011 [41].

The International Organization for Vine and Wine (OIV) has agreed on potential chemical hazards related to materials that come into contact with grapes, must, and wine, among other hazards, which are summarized in Table 1 [57].

Table 1.

Potential identified hazards in the winemaking process regarding wine contact materials, the stage of their occurrence, and their source, according to OIV [57].

4. Chemical Substances Migrating to Wine

A significant number of studies has dealt with the migration of naturally occurring components of cork into wine, which may influence the organoleptic properties of wines like the color, flavor, astringency, and bitterness, and degrade its quality [14]. These naturally occurring compounds include low molecular-weight polyphenols such as gallic, protocatechuic, vanillic, caffeic, caftaric, ferulic, p-coumaric acids, and ellagic acids; vanillin, protocatechuic, coniferilic, and sinapic aldehydes, aesculetin, and aescopoletin [4,58,59,60,61], more complex polyphenols, the ellagitannins such as vescalagin, castalagin, grandinin, roburin, and mongolicain A/B [58,59,60], condensed tannins, pectic-derived polysaccharides [60], and suberic acid [4].

Degradation of the organoleptic properties of wine has also been related to a group of compounds known as “cork off-flavor” or “cork taint” compounds found in cork stoppers, causing musty and moldy taint in wines [14,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. These compounds include the following:

- (i)

- Haloanisoles: 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (2,4,6-TCA); 2,4-dichloroanisole (2,4-DCA); 2,6-dichloroanisole (2,6-DCA); 2,3,4,6-tetrachloroanisole (TeCA); pentachloroanisole (PCA); 2,4,6-tribromoanisole (TBA) [63,65,66,67,68,69,70];

- (ii)

- Geosmin and 2-Methylisoborneol (2-MIB) [62,63,65,68];

- (iii)

- Guaiacol and 4-methylguaiacol [62,63,69];

- (iv)

- 1-octen-3-ol and 1-octen-3-one [62,69];

- (v)

- Methoxypyrazines: 3-isopropyl methoxy pyrazine (IPMP); 3-isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazine (IBMP); 3,5-dimethyl-2-methoxypyrazine (MDMP) [14,62,65].

Most of these volatile compounds are metabolites produced in the presence of microorganisms either on the cork or in its environment and subsequently absorbed by the cork and eventually transferred to wine after sealing. The precursors of these metabolites may be naturally occurring substances like lignin in the case of guaiacol and lipids in the case of 1-octen-3-ol and 1-octen-3-one, or pesticides and biocides such as 2,4,6-trichlorophenol and other chlorophenols used as wood preservatives or plant protection products in the case of tricholoroanisole (2,4,6-TCA) [63]. Furthermore, the formation of 2,4,6-TCA and other chlorinated compounds has been related to the bleaching of corks, and it is considered to occur by chlorination of lignin compounds [63]. In particular, the mechanism of 2,4,6-TCA formation has been reported to involve microbial O-methylation of chlorophenols and chlorination of anisole [70]. It is noted that apart from the migration from contaminated cork stoppers or barrels, other origins of contamination of wine with these substances include the air pollution of the cellars [62,70] or the use of contaminated grapes [62,68].

Apart from the naturally occurring substances in corks or the metabolites of naturally occurring substances and degradation products of environmental contaminants like bleaching reagents and pesticides, there are other substances used in the manufacture of wine contact materials that could potentially migrate into wine. These contact materials include treated corks, stoppers, plastic bottles, cans, and paper bags, and the migrating substances concern antioxidants, lubricants, monomers, and plasticizers [35,36,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. These substances are related more to wine safety issues since they include compounds that have been related to human health risks, such as bisphenol A (BPA), which has been characterized as a potential endocrine-disrupting compound [81], and certain phthalates which have been classified for their toxicity according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 [82], and other substances of raised concern which are included in the EU control plan for certain substances migrating from materials and articles intended to come into contact with food [83].

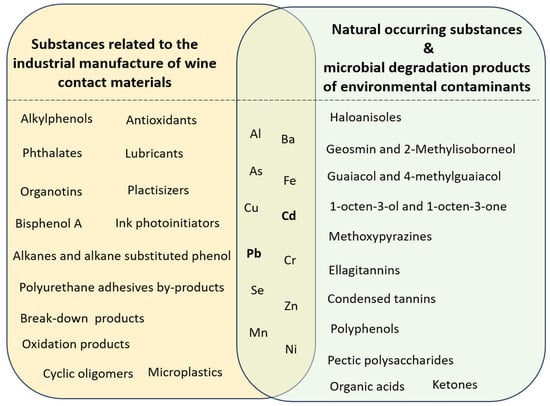

Based on the above, the following classification is proposed for the chemical substances migrating to wine, according to their origin, as illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Classification of migrating substances from wine contact materials [4,35,36,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80].

(i) Substances related to the industrial manufacture of wine contact materials: substances related to the manufacturing and use of plastics and glass (intentionally added substances and non-intentionally added substances, including micro and trace elements and microplastics).

(ii) Natural occurring substances and microbial degradation products of environmental contaminants

It is noted that micro and trace elements may originate naturally in packaging materials like cork and glass, or they may originate from the manufacturing of polymers and plastics.

The study of the migration of these substances is implemented by migration tests in order to investigate their transfer from the wine contact material into wine and, afterward, the application of specific analytical techniques for their identification and quantification in wine or wine simulant. Alternatively, the occurrence of suspect migrating substances is examined by direct analysis of wine without the application of a migration test. The present review of analytical methods focuses on the determination of the chemical substances that belong to category (i), namely substances related to the industrial manufacture of wine contact materials and are usually related to safety issues.

5. Wine Migration Studies on Chemical Contaminants

The wine packaging migration studies involve the selection of the following parameters: (i) the food contact material to be tested, (ii) the migration conditions (simulant or wine, temperature, time, type of test), (iii) the sample preparation of the food simulant or the wine, and (iv) the analytical technique for the identification and quantification of the compounds.

5.1. Migration Tests

Table 2 summarizes the migration studies that have been applied for the investigation of the migration of several chemical contaminants in wine or in relevant simulants. It is noted that in all studies, the contact article tested was the cork or plastic top.

Table 2.

Migration studies on wine and wine simulants.

Regarding the migration conditions, the tested simulants are mainly aqueous solutions of ethanol at concentrations of 12% [11,71,76], 15% [36], and 20% [74,75,76], acidified aqueous solution of 12% ethanol at pH equal to 3 [71], acidic aqueous solution 3% v/v acetic acid [74,75], while wine [72] and champagne at 11.5% vol [75] have also been used in migration tests. In most cases, either the whole article of cork with measured surface area or a specified quantity (g) of cork granules or shattered cork was immersed in a specified volume of simulant or wine, ranging between 30 and 250 mL [11,36,71,72,74,76]. In one study, the migration test was performed with 200 mL bottles sealed with tested corks horizontally laid [75]. The migration time/temperature applied was, in most cases, 10 days at 40 °C [36,71,76] or 10 days at 60 °C [74,75], which are specific conditions described in the Regulation EU 10/2011 as accelerated test conditions for contact times above 30 days at room temperature and below. One study investigating the presence of phthalates conducted the migration test at 70 °C for 2 h, but no positive findings were reported [11], while another study performed the test at room temperature for 30 days with intermediate data points for the investigation of organotins migration and quantifiable findings were reported [72]. It has been observed that migration values were higher at 20% ethanol compared to those at 3% acetic acid [74]. Furthermore, based on the present review, the migration of chemical contaminants to wine-based products with alcohol content higher than 20%, like liqueur and aromatized wine, has not been investigated until now. In this case, the appropriate simulant for the migration test would be an aquatic solution of 50% ethanol, according to European legislation [41].

5.2. Analytical Methods

After the completion of the migration test, the sample, which is the food simulant or the wine, is subjected initially to the sample preparation procedure in order to extract the analytes, remove interfering matrix substances, and have pre-concentration of the target compounds. Afterward, the obtained extract is analyzed using a proper analytical technique to identify the compounds and quantify them. The selection of the sample preparation steps and the analytical technique to be applied depend on the nature of the compounds to be determined (analytes) and the nature of the sample. According to the studies performed for the investigation of migrating substances from cork and plastic tops of wine, gas chromatography (GC) and liquid chromatography (LC) coupled in all cases to mass spectrometry (MS) [11,36,71,72,73,74,75] were used for the determination of organic compounds, while Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) were used for the elemental analysis [76].

5.2.1. Gas Chromatography

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry was used in the past for the determination of the phthalate plasticizer Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) after liquid–liquid extraction with dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) reporting non-detectable findings, below 50 ng/mL, without further details on the acquisition of mass spectrometric data [71]. GC-MS analysis has been reported for the determination of certain phthalates (dimethyl phthalate; DMP, dibutyl phthalate; DBP, benzyl butyl phthalate; BBP, and DEHP), alkylphenols (4-n-Nonylphenol; NP and 4-n-octylphenol; OP), BPA, and bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate (DEHA) with limits of detection at ppt level ranging between 17 ng/L (NP) and 451 ng/L (DEHP) [36]. The method included solid phase extraction with the polymeric sorbent Oasis HLB and elution with combinations of dichloromethane, hexane, and acetone prior to GC-MS analysis and acquisition in selected ion monitoring (SIM) mode using three ions per compound [36].

Gas chromatography was also used in the past for the determination of organotins after migration tests with agglomerated corks and wine [72]. Prior to GC analysis, hydride derivatization and headspace solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME) with poly-(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) coated fibers were applied, while the quantification of the derivatized organotins was performed with flame photometric detector (FPD) and their identification with a mass spectrometer in full scan mode and comparison of the spectrum with that of derivatized standards. According to the reported findings, monobutyltin in wine increased with time until it reached 24 μg of Sn/L after a 30-day period, while dibutyltin increased in the first 5 days and then was maintained around 4 μg of Sn/L [72]. The abovementioned studies concern target analysis for a limited number of compounds using standard compounds for the identification of the analytes.

An untargeted approach applying GC-MS methodology was recently reported for the screening of volatile compounds migrating from EVA corks to wine simulant [74]. Solid phase micro extraction (SPME) with PDMS fiber coating was used for the isolation of the analytes from the wine simulants. The acquisition was carried out in scan mode over the range of 50–450 m/z, and the identification of each migrant was based on the comparison of the spectra of each chromatographic peak unique to the sample to the NIST and WILEY mass spectra libraries, as well as on the analysis of commercial standards when available [74]. This study resulted in the identification of five compounds, three of them, the butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), its potential impurity 2,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-ethyl phenol, and 7,9-ditert-butyl-1-oxaspiro [4.5] deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione were identified with commercial standards. The other two eluted peaks were identified based on mass spectra library matches as the alkanes (i) 2,2,4,4,6,8,8-heptamethyl nonane and (ii) 2,2,4,6,6-pentamethyl heptane. There were two more eluted chromatographic peaks that could not be identified based on library matches; however, based on characteristic features of their spectra, it was hypothesized that they included branched alkanes. The identified BHT and 2,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-ethyl phenol belong to the intentionally added substances since they are included in the European Union List of the authorized compounds as additives or polymer production aids (Reg 10/2011) and their SMLs are 3 and 4.8 mg/kg, respectively. The alkanes and 7,9-ditert-butyl-1-oxaspiro [4.5] deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione belong to the Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIAS), and their origin was not concluded. The limits of detection (LODs) of the method ranged between 0.3 and 0.5 μg/kg, and the concentrations found were up to 15 μg/kg for BHT [74]. More detailed findings on the concentrations are presented in Table 2. It is noted that the present study used two simulants, 3% v/v aq. acetic acid and 20% v/v aq. ethanol, and it was observed that all concentrations were systematically higher in the ethanolic simulant [74].

Regarding the gas chromatography column used in the GC-MS migration studies for the determination of chemical contaminants from cork and plastic tops, this was, in most cases, a capillary column coated with 5% phenyl-95% dimethylpolysiloxane [36,72,74] or non-polar phenyl arylene polymer gas chromatography [71], virtually equivalent to (5%-phenyl)-methylpolysiloxane, and in the case of the determination of organotins with a flame photometric detector (FPD), 100% dimethylpolysiloxane [72].

5.2.2. Liquid Chromatography

Liquid chromatography coupled to low-resolution triple quadrupole mass spectrometry has been applied for the targeted analysis of phthalates [11], while ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled to ion-mobility and high-resolution time of flight (TOF) spectrometry has been applied for the wide-scope targeted and untargeted analysis of IAS and NIAS migrating from cork to wine simulants [74,75] and champagne [75]. The analytical column used in all cases concerned reversed phase C18 sorbent, and the mobile phase consisted of water, and methanol acidified either with formic acid [74,75] or with acetic acid [11]. The electrospray ionization (ESI) interface was operated in positive polarity for the phthalates [11] and for the compounds derived from polyurethane adhesives [75], while for the untargeted approach, the ESI was operated in positive and negative polarity mode [74].

In more detail, the LC triple quadrupole MS/MS method for the determination of phthalates used reference standards of BBP, DBP, DEHP, Di-isodecylphthalate (DiDP), Di-isopropyl phthalate (DIP), Di-isononylphthalate (DiNP), Dimethyl isophthalate (DMIP), Diallylphthalate (DA), and Diphenyl phthalate (DPP). Two selected transitions were monitored for each compound, and their ratio was used to verify the identity of the analytes in samples in addition to the retention time. The method was validated for four selected phthalates, and the LOQs ranged from 0.15 mg/L (DBP) up to 0.57 mg/L (DiNP), while no quantification results from the migration tests were reported [11].

Recently, a wide-scope study applying ultra high pressure liquid chromatography in combination with ion mobility–quadrupole time of flight analyzer (UPLC-IM-Q/TOF) focused on the determination of compounds derived from polyurethane adhesives used in champagne cork tops [75]. The analytical methodology started with the analysis of the migration extracts of the wine simulants and the analysis of the diluted champagne samples, 1/10 v/v with ultrapure water by UPLC-IM-Q/TOF. Ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) constitutes an additional identification feature. The ions need a “drift time” to cross the drift cell, which is used for the generation of a collision cross-section (CCS) value for each compound. The CCS value is an intrinsic property of the molecule and is related to its 3D conformation. It is a useful tool to discriminate between isobaric and isomeric species. The generated spectra after ion mobility are simplified because the fragment ions of a detected compound are associated with the precursor ion for that compound using not only the retention time but the drift time as well. Data were acquired in the range of 50–1000 m/z, and data independent analysis was set to high-definition mass spectrometry. This technique provided separation of the LC eluted compounds by means of ion mobility, mass accuracy, fragment ions, and retention time. The unknown compounds were first attributed to an elemental composition based on the m/z of the precursor ion. Afterward, a database search using ChemSpider proposed compounds, including their structure for each elemental composition, and then in silico fragmentation was applied to each structure in order to compare the m/z of the proposed fragment ions to the m/z of the actually generated fragment ions. The application of this analytical methodology resulted in the identification of twelve new compounds, which were amines, amides, and urethanes, formed from the reaction between the isocyanates and acetic acid or ethanol, used as food simulants, and in the identification of four new compounds generated from the reaction between the diisocyanates and malic acid or tartaric acid contained in champagne. The identified compounds were subsequently quantified or semi-quantified using UPLC coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in the MRM mode and certified standards of 1,6-hexanediamine and isophorone diamine. Limits of detection were below 5 μg/kg in the food simulants and below 30 μg/kg in champagne samples, while the migration levels ranged from 70 to 721 μg/kg [75].

The same UPLC-IM-Q/TOF methodology was applied for the determination of migrating substances from EVA corks into aqueous simulants of alcohol 20% and acetic acid 3% [74]. After the migration test, no sample preparation was performed, and the extracts were analyzed through reversed phase liquid chromatography in positive and negative ESI polarity, acquiring data between 50 and 1000 m/z in high-definition mode. The compounds that were identified in this wide-scope untargeted UPLC-IM-Q/TOF study to migrate from EVA corks into aqueous simulants were, in total, forty-three. In more detail, the findings included seven additives, namely one cross-linking agent (Triethylene glycoldimethacrylate), four antioxidants (Butyl 4-hydroxybenzoate, Irgafos 168, Irganox 1076, Irganox 1010), and the degradation product of the latest, as well as two lubricants (N,N′-Ethylene bis oleamide or EBO and N,N′-1,2-ethanediylbisoctadecanamide). Furthermore, thirty compounds were identified as cyclic co-oligomers of the general formula (C2H4)n(C4H6O2)m with “n” ranging between 1 and 13 and “m” between 2 and 4. Furthermore, four compounds were identified as two amides bonded by ethylene. Reference standards were used for unequivocal identification of the additives, the degradation product of Irganox 1010, and the oxidation product of Irgafos 168 (Irgafos 168 OXO). The reported limits of detection ranged from 1 μg/kg for Butyl 4-hydroxybenzoate up to 22 μg/kg for Irganox 1010, and the quantifiable concentrations of the migrating substances ranged between <5.5 and 654 μg/kg [74]. It is noted that the present study used two simulants, 3% v/v aq. acetic acid and 20% v/v aq. ethanol, and it was observed that all concentrations were systematically higher in the ethanolic simulant, as observed in the GC findings [74]. Multivariate analysis, in particular an orthogonal partial least-squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA), was performed on blank samples and extracts in order to identify the components/markers actually migrating in the simulant samples in both untargeted studies [74,75].

5.2.3. Elemental Analysis

The migration of elements from cork stoppers to aqueous alcoholic simulants has been investigated with inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP-AES) for major and minor element determination (Ba, Mn, and Al), while a quadrupole-based inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS) was used for trace element determination (Cr, Fe, Ni, Cu, Zn, Pb, Cd, As, Se) [76]. The effect of ethanol on the quantification of the elements was investigated, and it was shown that its presence is the main matrix effect in the determination of some elements like Mn and Fe, making the use of ethanol matrix standards compulsory for the generation of calibration curves. On the contrary, for other elements like Pb, Cd, Ni, Fe, and Cu, it was shown that the use of the internal standard allows appropriate correction for the presence of ethanol in the solution matrix. The quantified concentrations, expressed as micrograms per kilogram of cork, ranged between 4 μg kg−1 (Cd) and 28,000 μg kg−1 (Al).

5.2.4. Gravimetric Analysis

One study focusing on the cork–wine interaction and in particular on the migration of non-volatile compounds, in addition to liquid absorption, performed migration experiments using two types of cork stoppers, natural and 1 + 1 technical (with an agglomerate cork body and a washer of natural corkwood glued on both ends) [84]. Bottles of 375 mL capacity were filled with 12% v/v aqueous alcohol as wine simulant and were stored laid down at 16 °C and relative humidity of 55% ± 15% for 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. Overall migration was measured by eliminating the wine simulant in a rotary evaporator and drying the residue at 103 °C. Overall migration was the weight of the dry residue per stopper. The maximum values obtained were 20.20 and 6.18 mg/stopper for 1 + 1 technical and natural cork stoppers, respectively. In addition, absorption and overall migration were assessed by univariate variance analysis using a complete factorial model and cork stopper type, surface treatment, and contact time as fixed factors. The results of the statistical analysis demonstrated that the contact time, the type of cork stopper, and the surface treatment of the stopper affect the cork–liquid interaction phenomenon. In more detail, regarding overall migration, technical cork stoppers (1 + 1) produced higher values from six months on compared to the natural cork stoppers. In addition, it was shown that surface treatment produced a relatively small increase in overall migration, around 2 mg/stopper, an amount that seemed to remain constant and independent of the type of cork stopper and contact time [84].

6. Wine Analysis Studies on Potential Migrating Substances

During the literature review, a number of studies were found on the analysis of wine for the determination of chemical contaminants that could potentially migrate from packaging material or even from other materials that wine comes into contact during production like vats and plastic tubing, but these studies did not include the step of migration testing [35,77,78,79,80,85]. Despite the lack of a migration test, studies on the determination of significant contaminants in wine that could be related to migration from packaging material are reported and summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Determination of potential migrating substances in wine without migration testing.

Phthalates are a group of additives that raise concern, and their occurrence in wine has been investigated in several studies [77,78,79]. In particular, phthalates have been determined in wine samples packaged in aseptic plastic laminate paperboard cartons (tetrapacks) by GC-MS after QuEChERS extraction with acetonitrile [77], in a significant number of market-ready French wine samples by GC-MS after liquid–liquid extraction with isohexane [78], and in table wines processed and stored in stainless steel vats and in fortified wines matured in oak casks by GC-MS after HS-SPME with PDMS/DVB fibers [79]. Dibutyl phathalate (DBP) was the compound most frequently detected with the highest concentrations up to 2.212 mg/kg [79], while BBP, DEHP, and DOP (di-n-octyl phthalate) were reported to be detected, and quantified [77,78,79]. The origin of the phthalates is not clear since from the very beginning of the winemaking until bottling and storage, the raw materials, the intermediate must, and the final product are coming into contact with a variety of materials like vats, pipes, tanks, and hoses coated with epoxy resin. A study of various materials frequently present in wineries revealed that a relatively large number of polymers sometimes contained high concentrations of phthalates. However, the epoxy resin coatings used on vats represented the major source of contamination [78].

Other additives that have been determined in wine and correlated with food contact materials are BPA in wine packaged in PET bottles with aluminum caps [35], as well as in wine packaged in aseptic plastic laminate paperboard cartons (tetrapacks) [77]. The later study also determined the alkylphenol OP and DEHA [77]. Furthermore, the ink photoinitiators benzophenone, 2-isopropylthioxanthone (ITX), and 1-hydroxycyclohexyl-1-phenyl ketone have been determined in wine samples of polycoupled carton packaging by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry [80].

Another category of contaminants of concern is microplastics [86]. Microplastics were quantified in white wines, which were capped with synthetic polyethylene stoppers, by an optical microscope and contained up to 5857 particles L−1 but lacked chemical characterization [85]. In addition, micro-Raman spectroscopy (μRaman) was used for the identification of microplastic particles in white wines, and several difficulties in the analysis of this complex matrix with high organic matter are discussed [85]. The study is unique in the field of the determination of microplastics in wine; however, further research on the development of more robust and accurate methods, in addition to migration testing, would elucidate the migration of micro or even nanoplastics in wine.

7. Discussion on the Findings of Wine Migration and Wine Analysis Studies

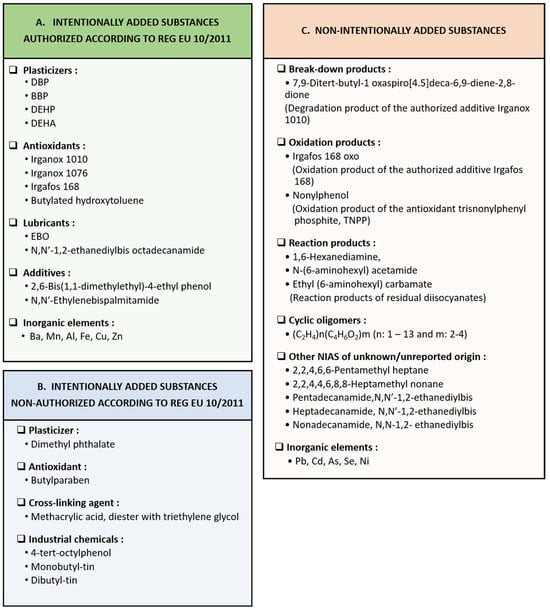

The migration studies that have been implemented to determine industrial chemical contaminants migrating from wine contact materials are limited to the investigation of cork stoppers and other types of closures. The identified migrating compounds include (A) intentionally added substances that are authorized for use in the manufacture of plastics according to Reg EU 10/2011, (B) intentionally added substances that are not authorized according to Reg EU 10/2011, and (C) non-intentionally added substances as presented in Figure 2. The corresponding concentration levels are reported in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Categories of detected migrating compounds from cork stoppers and tops. (A) intentionally added substances authorized for use in the manufacture of plastics according to Reg EU 10/2011, (B) intentionally added substances that are not authorized according to Reg EU 10/2011, and (C) non-intentionally added substances [36,72,74,75,76].

The studies that involved wine analysis aiming at the determination of known migrating compounds investigated samples packaged in PET bottles with and without aluminum cups for the determination of the monomer BPA [35], as well as wine samples in polycoupled carton packaging for the determination of ink photoinitiators [80]. The determination of phthalate plasticizers was investigated in a big sample of market-ready French products [78] and in table wines processed in stainless steel tanks and matured in oak casks [79]. Finally, another study was conducted for the determination of phthalate, DEHA, alkylphenols, and BPA in wine samples in aseptic plastic laminate paperboard cartons (tetrapacks) [77]. Among the determined analytes, DBP (2.212 mg/kg), DEHP (1.1317 mg/kg), BPA (30 ng/mL), and benzophenone (217 μg/L) presented the maximum concentrations, while for DBP, the maximum quantified concentration (2.212 mg/kg) exceeded the SML of the regulation (0.3 mg/kg).

In order to evaluate the safety of the tested wine contact materials or the actual wine samples, all the organic compounds quantified in migration studies and in wine analysis studies, which are intentionally added substances included in Reg EU 10/2011, are listed in Table 4 along with the specific migration limit (SML) where it is established. Their code number used in the regulation (FCM sub no), the CAS no, the molecular formula, the molecular weight, and their function in plastic manufacturing are also given. The data in Table 4 show that all the findings are in compliance with the SMLs, except for the plasticizer DBP, which has been found to exceed the SML in certain cases of wines [78]. In addition, Table 5 presents the corresponding findings for the inorganic elements that are included in Regulation EU 10/2011 obtained from a migration study [76]. It is shown that in all cases where there are reported results, the concentration levels are in compliance with the SMLs. However, it should be noted that this study determined quantifiable concentrations of Pb, Cd, As, Se, and Ni, which are given in μg per kilogram of cork. According to Reg 10/2011, salts of these elements are not allowed to be used in the manufacture of plastic materials. As it is already mentioned, it is not easy to identify the source of the occurrence of the inorganic elements since they are naturally occurring elements, environmental pollutants that could have been absorbed in the cork or actually contained in raw materials used in the manufacture of cork.

Table 4.

Intentionally added organic substances quantified in migration studies and in wine analysis included in the Union list of Reg EU 10/2011. FCM sub no: The food contact material substance number as coded in the Regulation.

Table 5.

Concentration levels of inorganic elements quantified in migration studies in hydroalcoholic solutions, 12% ethanol and 20% ethanol, and included in the Union list of Reg EU 10/2011 along with their SMLs [76].

Although the abovementioned studies [35,77,78,79,80] investigate the occurrence of potential migrating substances by analyzing commercially available wine samples in different packaging and contact materials, they do not include migration experiments but only the analysis of the wine samples. This is a crucial point since during winemaking, starting from the harvesting of grapes to the bottling of the finished product and storage, there are a number of processes involved and a number of pathways that chemical substances could contaminate the product at any stage of the processing. Therefore, when the objective is to study the behavior of a particular packaging material, ideally, migration testing should be performed in order to generate data before and after the contact between the wine or simulant and the tested material. No such studies were found on the migration of chemicals from bottles or other packaging such as PET, cans, or tetrapacks described in Section 2.

Moreover, the significance of conducting the migration studies with real food in addition to simulants has been highlighted [75], especially in cases where chemical interactions between the constituents of the contact material and constituents of food are possible, and they can lead to the formation of new unknown substances that would not be observed with the simulants. An example is the reaction between the organic acids contained in the champagne and the residual diisocyanates monomers from polyurethane (PU) adhesives. Furthermore, it has been shown that accelerated migration testing using food simulants may result in overestimated migration findings, especially at high temperatures in ethanolic simulants. Therefore, more realistic and representative testing conditions should be applied in order to show compliance with the specific migration limits [10].

Regarding the migrating organic compounds that are related to the industrial manufacture of packaging or generally the manufacture of wine contact materials, it is demonstrated that they include small compounds like 1,6-hexanediamine and BPA up to bigger compounds like cyclic oligomers. Oligomers are composed of a certain number of repeating units and a combination of the monomers used in polymeric synthesis; these substances are typically found in plastics with chain lengths ranging from dimers up to decamers in both cyclic and linear conformations. Oligomers can originate from side reactions occurring during the polymerization process, which are thermodynamically favored [48,49,50]. Several series of PET oligomers have already been identified and quantified in plastic food contact materials [50] and in teabags [87], and their toxicity has been assessed in silico [87]. Taking into consideration that PET bottles are used for wine packaging, it would be of high interest to investigate the potential migration of PET oligomers into wine.

Regarding the analysis of the aforementioned chemical substances, there is an analytical challenge highlighted in the literature on the determination of phthalates, which is related to their ubiquitous presence in the laboratory environment and equipment, possibly leading to false positives or overestimated results [88,89]. Recommendations for the limitation of contamination of the samples during analysis include (i) analysis in a separate room with air filters, (ii) replacement of plastic laboratory materials with glass, stainless steel, aluminum Teflon, and PTFE, and (iii) avoidance of personal care products by the analyst [89]. In order to address the existing contamination, the use of an increased number of blanks during analysis is proposed, and of course, the analytical tool of internal standardization for the quantification by the use of isotopically labeled internal standards is proposed [89].

8. Mitigation Measures for Migrating Compounds from Wine Contact Materials

The International Organization for Vine and Wine (OIV) has published a guide on the identification of hazards, critical control points, and their management in the wine industry, which includes chemical substances related to migration from wine contact materials (Table 1) and proposes preventive measures such as (i) good agricultural and viticultural practices, (ii) suppliers control, (iii) hygienic design for buildings, facilities, and equipment, (iv) maintenance plan for buildings, facilities, and equipment, (v) cleaning and disinfection plan, and (vi) setting of Critical Control Point at maturation in oak depending on the products produced [57].

Specifically for phthalates, which are among the main wine industry hazards related to wine contact materials, an even more detailed management of their occurrence in wine has been proposed from an HACCP point of view [90]. The preventive measures include (i) the use of food-quality material for grape and wine contact, which should be free of phthalates, (ii) special attention to old pipes constructed before the enforcement of the Regulation related to plastics and phthalates, and (iii) the use of non-plastic materials such as pipes made of stainless steel [90]. The control measures include the control of the food quality standard of the wine contact materials and their supply from a certified provider, while the verification for compliance to the acceptable levels of the regulated phthalates should be performed by wine analysis by an accredited laboratory [90].

Although there is no official corrective measure for the removal of phthalates from wine that contains them above the regulated limits, the use of nanomaterials synthesized by modification of clay minerals has been proposed for the removal of phthalates from wine at the lab level [91].

9. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The industrial migrating substances in wine include intentionally added substances (IAS) of known identity, listed in the European Union authorized catalog, requiring a targeted approach for their determination. On the other hand, it is shown that non-intentionally added substances (NIAS) of known and unknown identity can also migrate, and with advanced, high-resolution analytical tools, researchers have started detecting and identifying them. However, these studies are very limited in the field of wine contact materials. It is emphasized that the range of chemical substances migrating in wine needs to be further explored as it has been highlighted in general for alcoholic beverages [19]. In all cases, migrating IAS and NIAS must be identified at the highest degree of confidence and accurately quantified at the lowest possible concentrations [46]. Identification and quantification data of migrating substances in combination with chemometric tools (in silico) can contribute to the implementation of an efficient toxicological risk assessment and to the proposal of appropriate specifications of not adequately studied NIAS and IAS. Consequently, based on the risk assessment, suitable actions and measures can take place to control wine safety and quality, such as the proposal of specific migration limits.

For the above reasons, comprehensive workflows of target, suspect, and non-target analysis, which have been applied for the determination of chemical contaminants in environmental samples, trying to cover the maximum chemical space possible [92,93,94,95], could also be applied for the determination of migrating substances to wine and beverages. These workflows use identification features of retention time, prediction of retention time, m/z of the precursor ion, fragmentation pattern, and CCS values after the application of ion mobility mass spectrometry. In addition, taking into consideration that in many cases, there is no availability of standard substances, semi-quantification models are also used to determine the concentration levels of suspect and non-target screening findings [93,95].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C.M.; investigation, N.C.M., A.T. and E.D.T.; resources, N.S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.M., A.T. and E.D.T.; writing—review and editing, N.C.M., A.T., E.D.T. and N.S.T.; visualization, N.C.M.; project administration, N.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full name |

| BBP | Butyl benzyl phthalate |

| BDE | 2,2,4,4-Tetrabromodiphenyl ether |

| BHT | Butylated hydroxytoluene |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| DA | Diallylphthalate |

| DBP | Dibutyl phthalate |

| DEHA | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) adipate |

| DEHP | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate |

| DiDP | Di-isodecylphthalate |

| DiNP | Di-isononylphthalate |

| DIP | Di-isopropyl phthalate |

| DMIP | Dimethyl isophthalate |

| DMP | Dimethyl phthalate |

| DOP | Di-n-octyl phthalate |

| DPP | Diphenyl phthalate |

| EBO | N,N’-Ethylene bis oleamide |

| EDAB | Ethyl-4-dimethylaminobenzoate |

| EHDAB | 2-Ethylhexyl-4-dimethylaminobenzoate |

| EVA | Ethylene-vinyl acetate |

| IRGACURE 184 | 1-Hydroxycyclohexyl-1-phenyl ketone |

| ITX | 2-Isopropylthioxanthone |

| NP | 4-n-Nonylphenol |

| OP | 4-n-Octylphenol |

References

- James, A.; Yao, T.; Ked, H.; Wanga, Y. Microbiota for production of wine with enhanced functional components. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrelia, S.; Di Renzo, L.; Bavaresco, L.; Bernardi, E.; Malaguti, M.; Giacosa, A. Moderate Wine Consumption and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation Internationale de la Vigne et du Vin. State of the World Vine and Wine Sector in 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/documents/OIV_State_of_the_world_Vine_and_Wine_sector_in_2022_2.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Gancel, A.-L.; Jourdes, M.; Pons, A.; Teissedre, P.-L. Migration of polyphenols from natural and microagglomerated cork stoppers to hydroalcoholic solutions and their sensory impact. OENO One 2023, 57, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili Sadrabad, E.; Hashemi, S.A.; Nadjarzadeh, A.; Askari, E.; Akrami Mohajeri, F.; Ramroudi, F. Bisphenol A release from food and beverage containers–A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 3718–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbowiak, T.; Gougeon, R.D.; Alinc, J.B.; Brachais, L.; Debeaufort, F.; Voilley, A.; Chassagne, D. Wine Oxidation and the Role of Cork. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 50, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, I.; Lopes, P.; Oliveira, A.S.; Amaro, F.; Bastos, M.d.L.; Cabral, M.; Guedes de Pinho, P.; Pinto, J. The Impact of Different Closures on the Flavor Composition of Wines during Bottle Aging. Foods 2021, 10, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twede, D. The packaging technology and science of ancient transport amphoras. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2002, 15, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombre, C.; Rigou, P.; Chalier, P. The use of active PET to package rosé wine: Changes of aromatic profile by chemical evolution and by transfers. Food Res. Int. 2015, 74, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Welle, F. Chemical migration from beverage packaging materials—A review. Beverages 2020, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendón, R.; Sanches-Silva, A.; Bustos, J.; Martín, P.; Martínez, N.; Cirugeda, M.E. Detection of migration of phthalates from agglomerated cork stoppers using HPLC-MS/MS. J. Sep. Sci. 2012, 35, 1319–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, G. Recent development in beverage packaging material and its adaptation strategy. Trends Beverage Packag. 2019, 16, 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Crouvisier-Urion, K.; Bellat, J.P.; Gougeon, R.D.; Karbowiak, T. Gas transfer through wine closures: A critical review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.; Lopes, P.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Cork, a Natural Choice to Wine? Foods 2022, 11, 2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D. Innovative Packaging for the Wine Industry: A Look at Wine Closures; Virginia Tech Food Science and Technology: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2008; p. 24061. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, C.; Zigarelli, V.; De Feo, G. Attitudes of a sample of consumers towards more sustainable wine packaging alternatives. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; De Feo, G. Comparative life cycle assessment of alternative systems for wine packaging in Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revi, M.; Badeka, A.; Kontakos, S.; Kontominas, M.G. Effect of packaging material on enological parameters and volatile compounds of dry white wine. Food Chem. 2014, 152, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, N.X.; Bayen, S. An overview of chemical contaminants and other undesirable chemicals in alcoholic beverages and strategies for analysis. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3916–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, K.; Bugusu, B. Food packaging-Roles, materials, and environmental issues: Scientific status summary. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, R39–R55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson-Witrick, K.A.; Pitts, E.R.; Nemenyi, J.L.; Budner, D. The Impact Packaging Type Has on the Flavor of Wine. Beverages 2021, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Valdés, A.; Mellinas, A.C.; Garrigós, M.C. New trends in beverage packaging systems: A review. Beverages 2015, 1, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, M.; Uedono, A.; Hotta, A. Recent Progress in Gas Barrier Thin Film Coatings on PET Bottles in Food and Beverage Applications. Coatings 2015, 5, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Move over, Glass: Amcor’s New Wine Bottle is 100% Recycled PET|Packaging Dive. Available online: https://www.packagingdive.com/news/rpet-wine-bottle-amcor-plastic-ron-rubin-CO2-emissions/688809/ (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Dombre, C.; Rigou, P.; Wirth, J.; Chalier, P. Aromatic evolution of wine packed in virgin and recycled PET bottles. Food Chem. 2015, 176, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csiba-Herczeg, A.; Koteczki, R.; Lukács, B.; Balassa, B.E. Case study-based scenario analysis comparing GHG emissions of wine packaging types. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2023, 15, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmijková, D.; Švédová, B.; Růžičková, J. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in biochar originated from pyrolysis of aseptic packages (Tetra Pak®). Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 27, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TetraPak. Available online: https://www.tetrapak.com/solutions/packaging/packaging-material/materials (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Maduwantha, M.I.P.; Jayasinghe, R.A. Possibilities of Development of Composite Materials from Tetra Pak and Metalized Film-Based Packaging Waste for Non-Structural Applications. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Sci. 2023, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, A.; Samyn, P.; Rastogi, V.K. Paper bottles: Potential to replace conventional packaging for liquid products. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022, 14, 13779–13805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frugalpac Frugalpac Frugal Bottle. Available online: https://frugalpac.com/frugal-bottle/ (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Berti, L.A. Effect on Wine of Type of Packaging. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1950, 1, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versari, A.; Ricci, A.; Moreno, C.P.; Parpinello, G.P. Packaging of Wine in Aluminum Cans–A Review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2023, 74, 0740022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, G.K.; Panjagari, N.R. Review on metal packaging: Materials, forms, food applications, safety and recyclability. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2377–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalbouris, A.; Kalogiouri, N.P.; Kabir, A.; Furton, K.G.; Samanidou, V.F. Bisphenol A migration to alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages–An improved molecular imprinted solid phase extraction method prior to detection with HPLC-DAD. Microchem. J. 2021, 162, 105846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, E.; Bono-Blay, F.; Cirillo, T.; Montuori, P.; Lacorte, S. Migration of phthalates, alkylphenols, bisphenol A and di(2-ethylhexyl)adipate from food packaging. Food Control 2012, 27, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.; Allison, R.B.; Goddard, J.M.; Sacks, G.L. Hydrogen Sulfide Formation in Canned Wines Under Long-Term and Accelerated Conditions. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2023, 74, 0740011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castle, L. Chemical migration into food: An overview. In Chemical Migration and Food Contact Materials, 1st ed.; Karen, A., Barnes, C., Sinclair, R., Watson, D.H., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Simoneau, C. Chapter 21 Food Contact Materials. In Comprehensive Analytical Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 733–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004 on Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) No 10/2011 on Plastic Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 Establishing a Common Organisation of the Markets in Agricultural Products and Repealing Council Regulations (EEC) No 922/72, (EEC) No 234/79, (EC) No 1037/2001 and (EC) No 1234/2007; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) No 251/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on the Definition, Description, Presentation, Labelling and the Protection of Geographical Indications of Aromatised Wine Products and Repealing Council Regulation (EEC) No 1601/91; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- The Importance of pH in Wine Making-Sensorex Liquid Analysis Technology. Available online: https://sensorex.com/ph-wine-making/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Geueke, B. FPF Dossier: Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIAS), FPF Dossier: Non-Intentionally Added Substances (NIAS) 2015 (zenodo.org); Zenodo: Geneve, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsochatzis, E.D. Food Contact Materials: Migration and Analysis. Challenges and Limitations on Identification and Quantification. Molecules 2021, 26, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsochatzis, E.D.; Lopes, J.A.; Hoekstra, E.; Emons, H. Development and validation of a multi-analyte GC-MS method for the determination of 84 substances from plastic food contact materials. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 5419–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenz, F.; Linke, S.; Simat, T. Linear and cyclic oligomers in polybutylene terephthalate for food contact materials. Food Addit. Contam. Part. A 2018, 35, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsochatzis, E.D.; Gika, H.; Theodoridis, G. Development and validation of a fast gas chromatography mass spectrometry method for the quantification of selected non-intentionally added substances and polystyrene/polyurethane oligomers in liquid food simulants. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2020, 1130, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoppe, M.; de Voogt, P.; Franz, R. Identification and quantification of oligomers as potential migrants in plastics food contact materials with a focus in polycondensates–A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerin, C.; Alfaro, P.; Aznar, M.; Domeño, C. The challenge of identifying non-intentionally added substances from food packaging materials: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2013, 775, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Commission Regulation (EU) 2022/1616 on Recycled Plastic Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Foods, and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 282/2008; European Union: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 84/500/EEC. Council Directive of 15 Oct. 1984 on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Ceramic Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Foodstuffs. 1984. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A31984L0500. (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- European Commission. Commission Directive 2005/31/EC of 29 April 2005 Amending Council Directive 84/500/EEC as Regards a Declaration of Compliance and Performance Criteria of the Analytical Method for Ceramic Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Foodstuffs; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and European Commission, Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Vine and Wine, Compendium Of International Methods Of Wine And Must Analysis, OIV-MA-C1-01 Maximum Acceptable Limits of Various Substances Contained in Wine, 2019 Issue. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/standards/compendium-of-international-methods-of-wine-and-must-analysis/annex-c/annex-c-maximum-acceptable-limits-of-various-substances/maximum-acceptable (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- International Organization of Vine and Wine, OIV Guide to Identify Hazards, Critical Control Points and Their Management in the Wine Industry, RESOLUTION OIV-OENO 630-2020. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/standards/oiv-guide-to-identify-hazards%2C-critical-control-points-and-their-management-in-the-wine-industry (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Varea, S.; García-Vallejo, M.C.; Cadahía, E.; Fernández de Simón, B. Polyphenols susceptible to migrate from cork stoppers to wine. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 213, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, J.; Fernandes, I.; Lopes, P.; Roseira, I.; Cabral, M.; Mateus, N.; Freitas, V. Migration of phenolic compounds from different cork stoppers to wine model solutions: Antioxidant and biological relevance. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2014, 239, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.F.; Coelho, E.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Coimbra, M.A.; Lopes, P.; Cabral, M.; Mateus, N.; Freitas, V. Migration of Tannins and Pectic Polysaccharides from Natural Cork Stoppers to the Hydroalcoholic Solution. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 14230–14242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnaar, P.P.; Gerber, P.; Booyse, M.; Jolly, N. Phenolic Compounds in Cork-Closed Bottle-Fermented Sparkling Wines. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2021, 42, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravero, M.C. Musty and Moldy Taint in Wines: A Review. Beverages 2020, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.S.; Figueiredo Marques, J.J.; San Romão, M.V. Cork Taint in Wine: Scientific Knowledge and Public Perception—A Critical Review. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 26, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buser, H.R.; Zanier, C.; Tanner, H. Identification of 2,4,6-trichloroanisole as a potent compound causing cork taint in wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1982, 30, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabizki, P.; Legrum, C.; Wegmann-Herr, P.; Fischer, C.; Schmarr, H.-G. Quantification of cork off-flavor compounds in natural cork stoppers and wine by multidimensional gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 977–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanola, R.; Subirà, D.; Salvadó, V.; Garcia Regueiro, J.A.; Anticó, E. Migration of 2,4,6-trichloroanisole from cork stoppers to wine. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2005, 220, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatonnet, P.; Labadie, D.; Boutou, S. Simultaneous assay of chlorophenols and chloroanisoles in wines and corks or cork-based stoppers application in determining the origin of pollution in bottled wines. J. Int. Sci. Vigne Vin. 2003, 37, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingart, G.; Schwartz, H.; Eder, R.; Sontag, G. Determination of geosmin and 2,4,6-trichloroanisole in white and red Austrian wines by headspace SPME-GC/MS and comparison with sensory analysis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 231, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerro, O.; Tena, M.T. Determination of odour-causing volatile organic compounds in cork stoppers by multiple headspace solid-phase microextraction. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1068, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Xie, Y.; Wu, T.; Wang, X.; Gao, J.; Tian, B.; Huang, W.; You, Y.; Zhan, J. Cork taint of wines: The formation, analysis, and control of 2,4,6-trichloroanisole. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, T.; Feigenbaum, A. Mechanism of migration from agglomerated cork stoppers. Part 2: Safety assessment criteria of agglomerated cork stoppers for champagne wine cork producers, for users and for control laboratories. Food Addit. Contam. 2003, 20, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Q. Search for the Contamination Source of Butyltin Compounds in Wine: Agglomerated Cork Stoppers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 4349–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, G. Survey on the Presence of Butyltin Compounds in Chinese Alcoholic Beverages, Determined by Using Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction Coupled with Gas Chromatography-Flame Photometric Detection. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6683–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, P.; Canellas, E.; Nerín, C.; Dreolin, N.; Goshawk, J. The migration of NIAS from ethylene-vinyl acetate corks and their identification using gas chromatography mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography ion mobility quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2022, 366, 130592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, E.; Vera, P.; Nerin, C.; Goshawk, J.; Dreolin, N. The application of ion mobility time of flight mass spectrometry to elucidate neo-formed compounds derived from polyurethane adhesives used in champagne cork stoppers. Talanta 2021, 234, 122632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, T.; Iglesias, M.; Anticó, E. Migration of Components from Cork Stoppers to Food: Challenges in Determining Inorganic Elements in Food Simulants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5690–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, E.; Cirillo, T.; Esposito, F.; Lacorte, S. Migration of monomers and plasticizers from packed foods and heated microwave foods using QuEChERS sample preparation and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatonnet, P.; Boutou, S.; Plana, A. Contamination of wines and spirits by phthalates: Types of contaminants present, contamination sources and means of prevention. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2014, 31, 1605–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perestrelo, R.; Silva, C.L.; Algarra, M.; Câmara, J.S. Monitoring Phthalates in Table and Fortified Wines by Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction Combined with Gas Chromatography−Mass Spectrometry Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 8431–8437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagratini, G.; Caprioli, G.; Cristalli, G.; Giardiná, D.; Ricciutelli, M.; Volpini, R.; Zuo, Y.; Vittori, S. Determination of ink photoinitiators in packaged beverages by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Chrom. A 2008, 1194, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]