Neuroprotective Benefits of Rosmarinus officinalis and Its Bioactives against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. AD and PD and Bioactive Rosemary Compounds with Health-Promoting Effects

3.1. Neurodegenerative Diseases

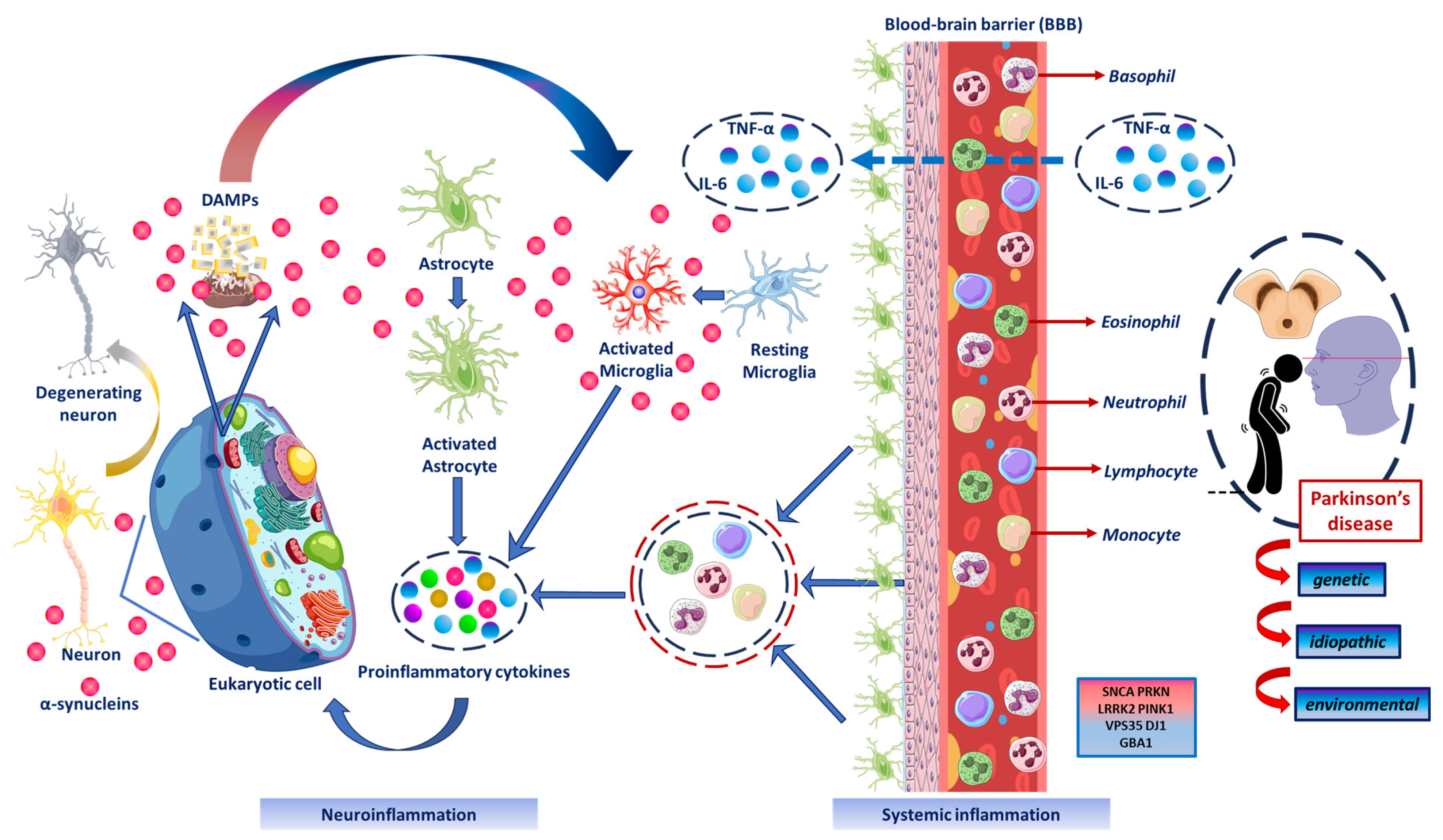

3.2. Parkinson’s Disease

3.3. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

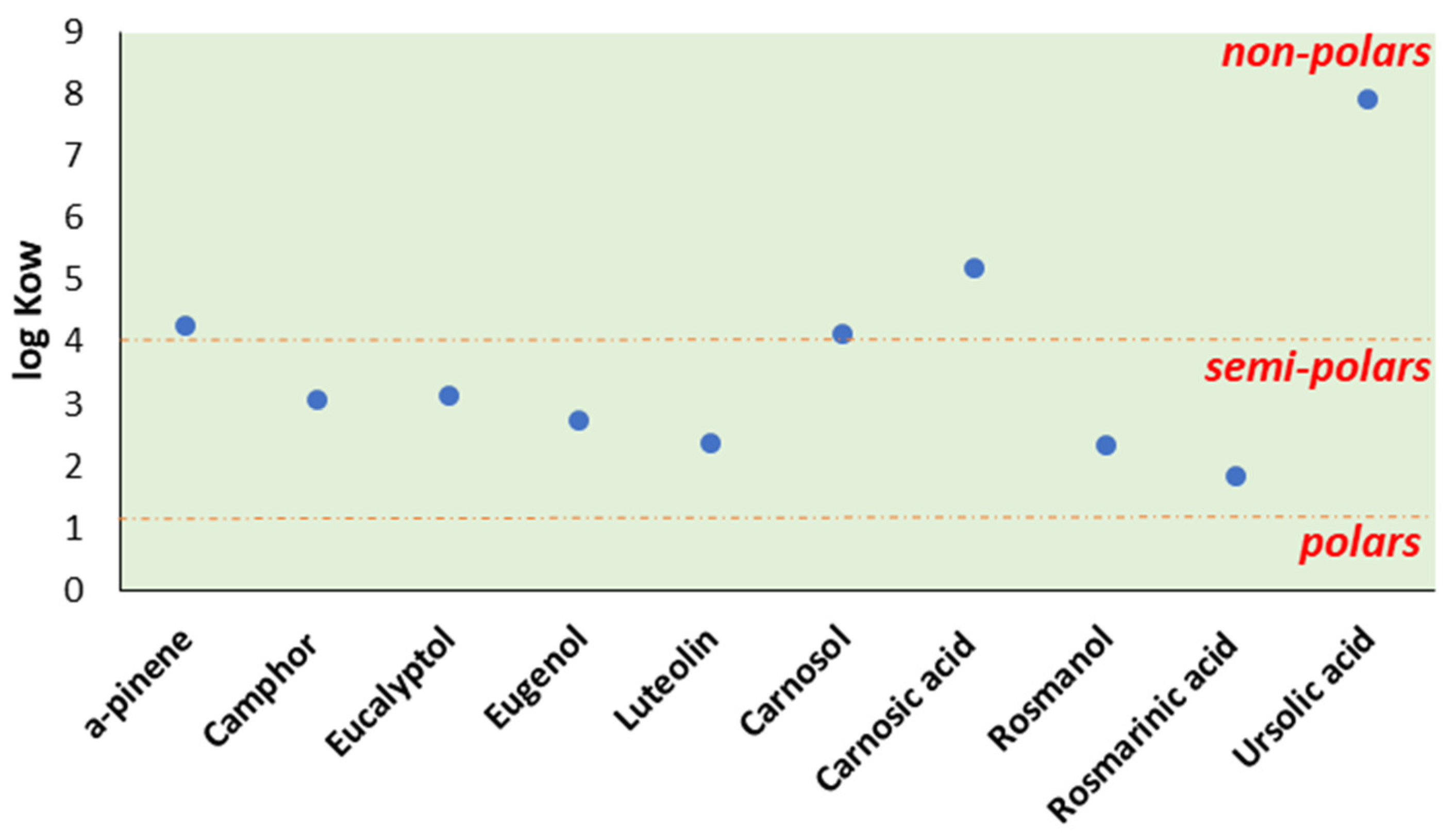

3.4. Rosemary and Its Bioactive Compounds

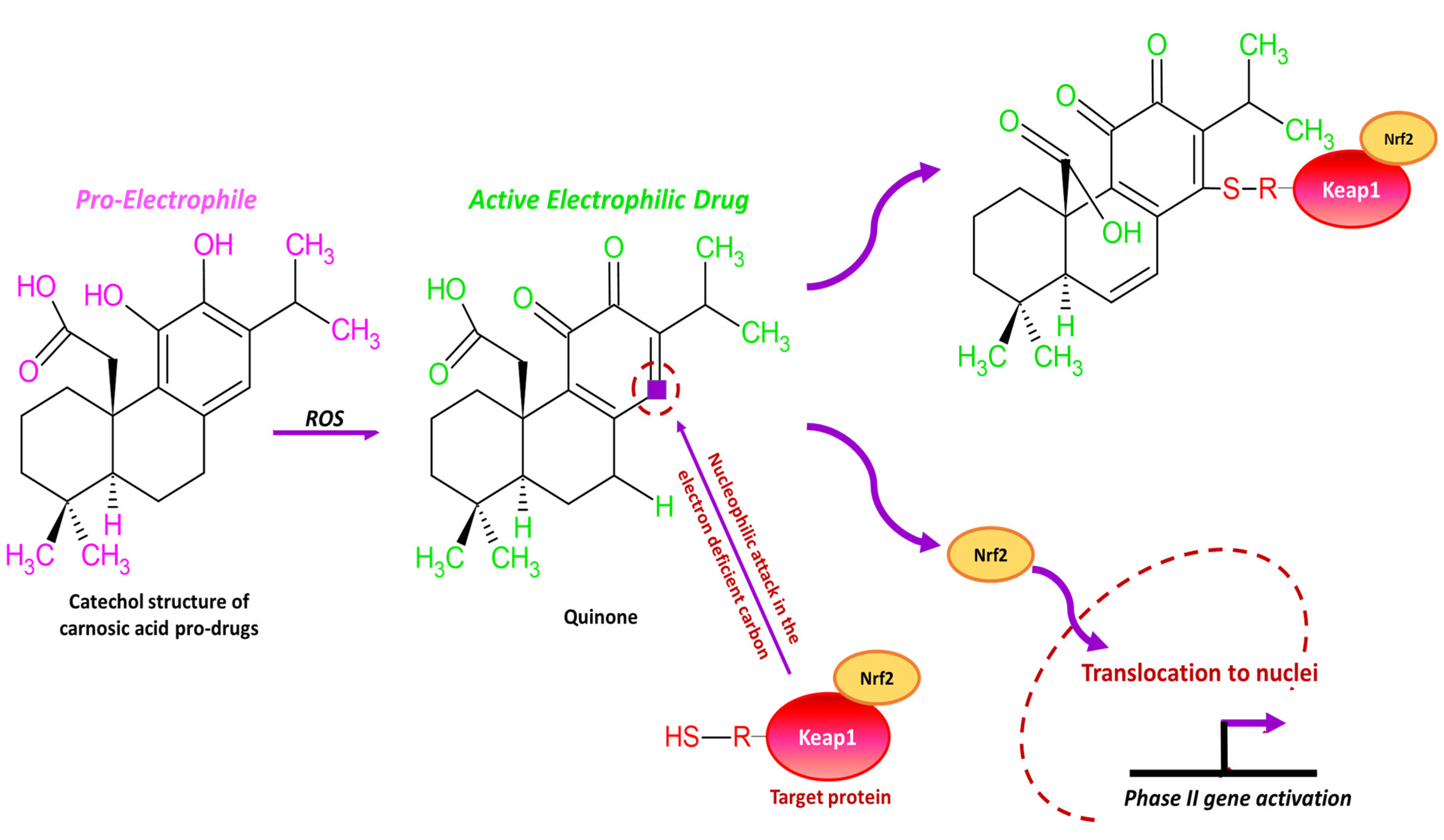

3.5. Carnosic Acid

3.5.1. In Vitro Health-Promoting Effects of Carnosic Acid against AD and PD

3.5.2. In Vivo Health-Promoting Effects of Carnosic Acid against AD and PD

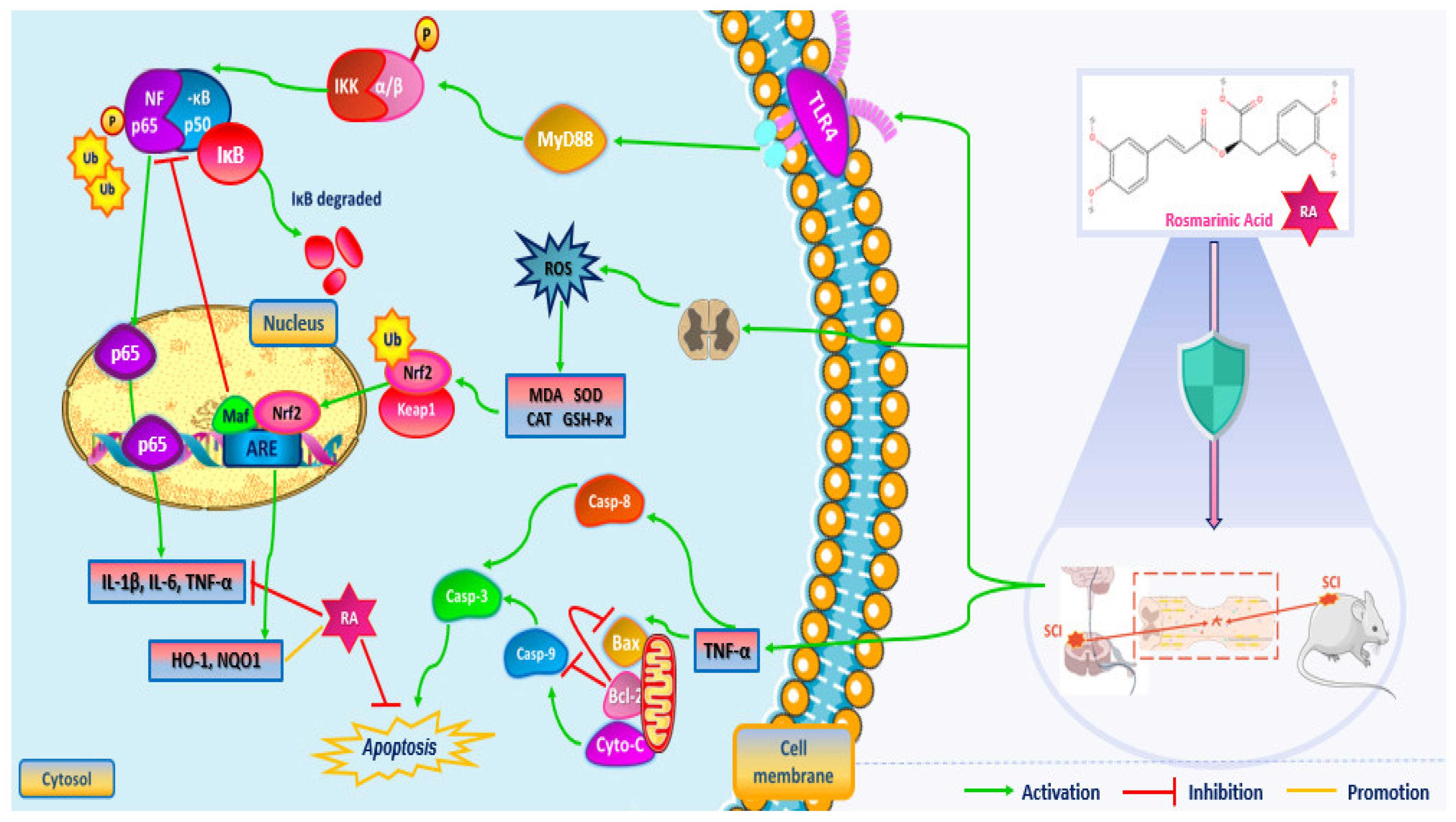

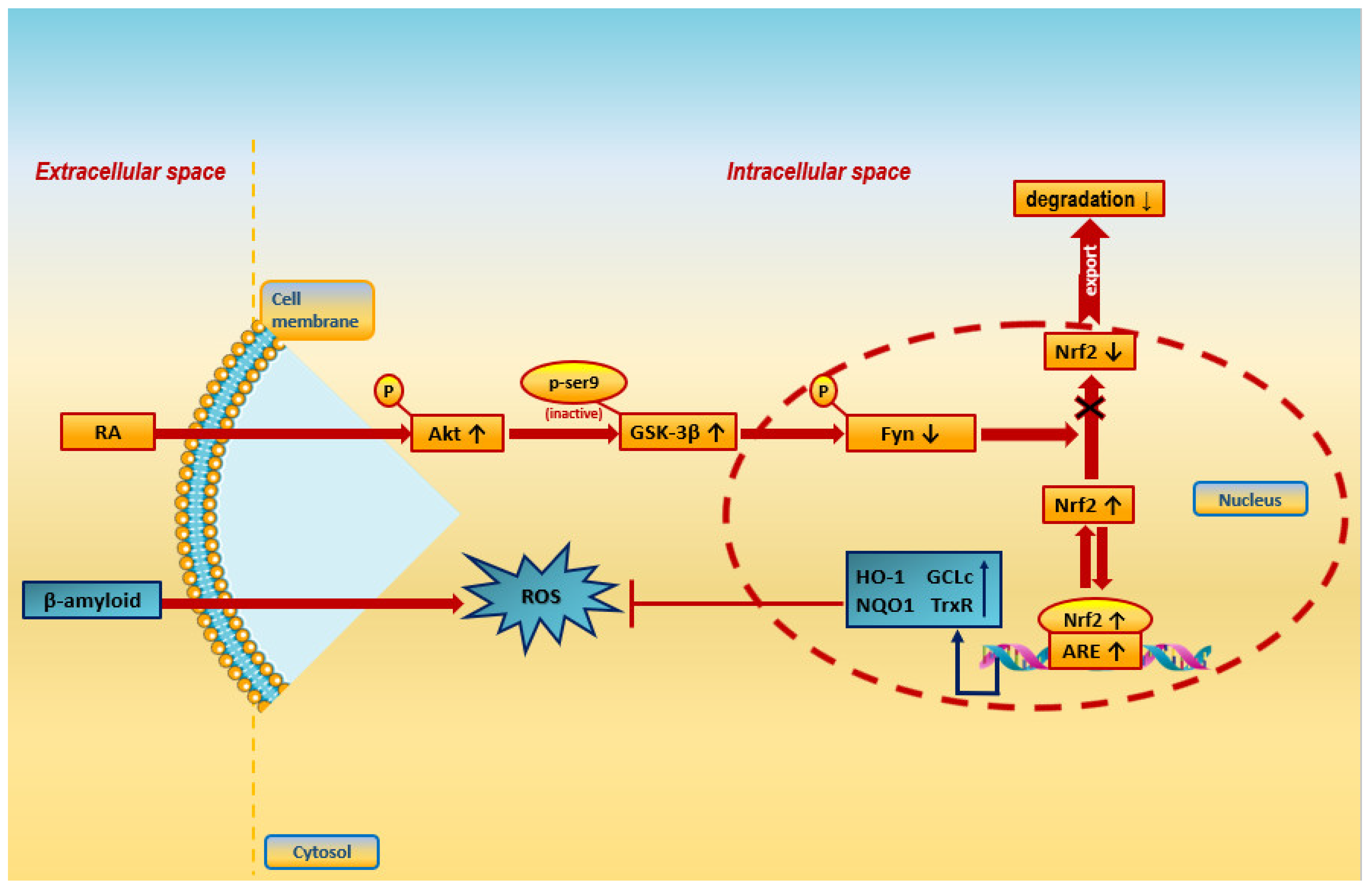

3.6. Rosmarinic Acid

3.6.1. In Vitro Health-Promoting Effects against AD and PD

3.6.2. In Vivo Health-Promoting Effects against AD and PD

3.7. Other Bioactive Compounds for Treating NDs

3.8. More Neuroprotective Properties of RO and Its Compounds

| Compound | Chemical Group | Structure | Effect | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosmarinic acid | Phenolic acid |  | Neuroprotective, antioxidant | [12] |

| Carnosic acid | Phenolic diterpene |  | Neuroprotective, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | [12,14] |

| Carnosol | Phenolic diterpene |  | Neuroprotective, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | [14] |

| Eugenol | Phenylpropanoid |  | Anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antioxidant | [103,104,124] |

| Camphor | Monoterpenoid |  | Neuroprotective, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | [123] |

| Luteolin | Flavonoid |  | Neuroprotective, antioxidant | [125] |

| Eucalyptol/1,8-cineole | Monoterpenoid |  | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | [126] |

| Ursolic acid | Triterpene |  | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective | [127] |

| a-pinene | Monoterpene |  | Neuroprotective, antioxidant | [107,128] |

| Rosmanol | Flavonoid |  | Neuroprotective | [109] |

| Hypothesis and Intervention 1 | Experimental Details | Study Results | Year of Study | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The neuroprotective effect of a rosemary EO was examined in vitro through the evaluation of H2O2-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells |

|

| 2010 | [129] |

| The impact of an R. officinalis EO on AD was examined in a mouse model |

|

| 2018 | [130] |

| The beneficial effects of an aromatherapy procedure in 28 older adults, where 17 of them had developed AD-type dementia, were evaluated |

|

| 2009 | [131] |

| The memory enhancement of an R. officinalis EO was explored in young and aged mice |

|

| 2014 | [116] |

| The study describes the effect of EOs on human short-term image and numerical memory |

|

| 2017 | [117] |

| This study evaluated the effect of lavender and rosemary EOs on the mood and cognitive performance of healthy volunteers |

|

| 2003 | [119] |

| This unprecedented study investigated the impact of a combination of rosemary and two other herbs on verbal recall in healthy humans and their clinical value for memory and brain function |

|

| 2017 | [132] |

| This study identified the antioxidative agents in rosemary and characterized their antioxidant effects in biological systems |

|

| 1995 | [121] |

| The effects of a rosemary extract and a spearmint extract, which both contained CA and RA, on cognition and memory in a SAMP8 mouse model that displayed rapid aging were studied |

|

| 2016 | [122] |

| Comparison of neuroprotective effect of R. officinalis RA and CA constituents through their impact on primary cultures of CGNs subjected to a variety of stressors |

|

| 2018 | [12] |

| The influence of RA and CA on seizures induced by PTZ were evaluated in this study |

|

| 2015 | [114] |

| In vivo study of RA effects in rats that were treated with 6-OHDA |

|

| 2012 | [9] |

| and SH-SY5Y cells treated with H2O2 |

|

| 2008 | [13] |

| RA activity in MPTP-treated mice |

|

| 2022 | [96] |

| RA in H2O2-treated N2A cells |

|

| 2014 | [88] |

| The inhibitory impact on AChE and BChE, as well as the metal-chelating ability, of 12 diterpenes including RA was examined |

|

| 2016 | [89] |

| RA’s inhibitory activity towards AChE and BChE was examined (RA was isolated from an R. officinalis extract and EO) |

|

| 2007 | [90] |

| AChE inhibition activity and antioxidant capacity of RA were examined to determine its potential as a candidate compound for AD treatment |

|

| 2014 | [91] |

| This study measured the AChE activities of phenolic acids and flavonoids individually or in combination |

|

| 2015 | [92] |

| The study assessed the structure–activity synergistic action of RA derivatives in terms of their anti-aggregation, antioxidant, and xanthine oxidase inhibition properties |

|

| 2017 | [93] |

| RA’s ability to inhibit fibrillization was assessed |

|

| 2017 | [94] |

| The study examined the effect of RA on Alzheimer amyloid peptide (A)-induced toxicity in cultured rat PC12 cells |

|

| 2006 | [95] |

| In an attempt to clarify whether RA prevents Aβ-induced peroxidation of lipids, and antioxidant defense and/or cholinergic damage, in addition to the main auditory deficits, Wistar rat were utilized |

|

| 2018 | [97] |

| The study assessed, in an Aβ25-35-injected mouse model, whether the administration of RA improved cognitive function |

|

| 2016 | [98] |

| An examination of the protective ability of RA as a natural ONOO− scavenger and preventing memory deterioration was conducted on a mouse model that was given an acute i.c.v. injection of A25-35 |

|

| 2007 | [99] |

| The effects of RA on the pathology related to ovariectomy and D-galactose injection (i.e., a double-insult in an AD model) were thoroughly assessed |

|

| 2015 | [100] |

| The outcomes of aging in a stress-induced tauopathy mouse model of chronic restraint stress and its possible effect were evaluated |

|

| 2015 | [101] |

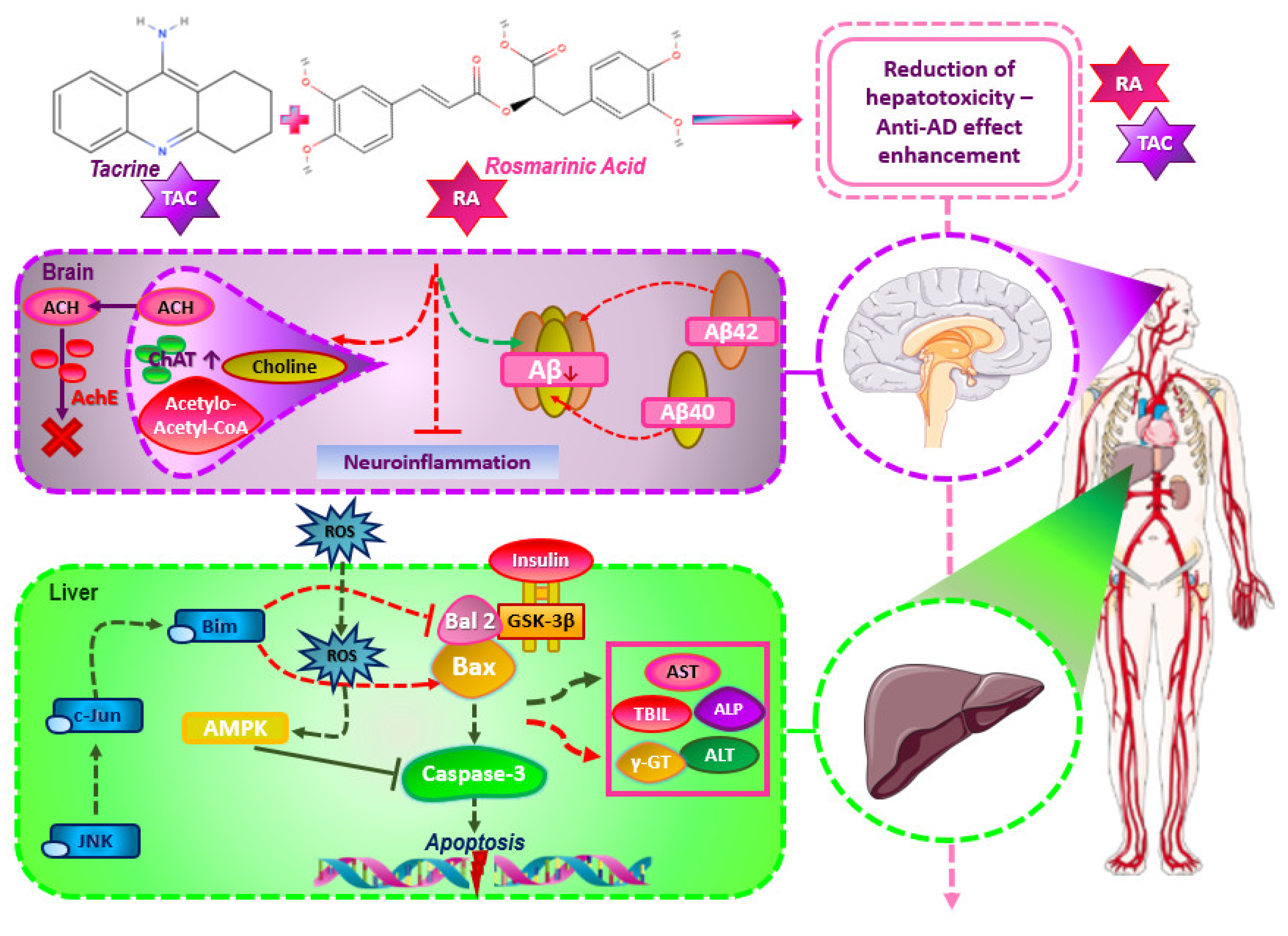

| The study investigated whether RA is able to suppress TAC’s hepatotoxicity to slow down the progression of AD in mice |

|

| 2023 | [133] |

| This study aimed to thoroughly assess the value of RA in protecting against SCI |

|

| 2016 | [115] |

| Investigation of CA’s neuroprotective effects and its effects on behavioral activity in a rat model of PD, which was induced by 6-OHDA |

|

| 2014 | [10] |

| Investigation of whether autophagy is correlated with CA’s neuroprotective activity against 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells |

|

| 2017 | [79] |

| Investigation of whether CA is neuroprotective against a paraquat (PQ)-induced PD in terms of cellular and mitochondrial-related redox parameters |

|

| 2016 | [17] |

| Study on whether R. officinalis-derived CA is able to protect against 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity via the upregulation of parkin both in vivo and in vitro in SH-SY5Y cells |

|

| 2016 | [16] |

| The established mechanism used by CA in the modulation of the neurotoxic impact of 6-OHDA in SH-SY5Y cells was observed |

|

| 2012 | [15] |

| The determination of whether CA can protect hippocampal neurons by reversing neurodegeneration in rats was this study’s main aim |

|

| 2011 | [86] |

| The study assessed whether CA’s administration owns a protective effect against memory loss induced by β-amyloid toxicity in rats |

|

| 2013 | [87] |

| The study in vitro examined the protective abilities of CA on primary neurons that were treated with oligomeric Aβ. In vivo on mouse models of AD after the delivery of CA, investigated learning and memory ability as well as synaptic damage |

|

| 2016 | [85] |

| This study investigated the possible use of CA to prevent MG-induced neurotoxicity |

|

| 2015 | [81] |

| The effect of CA on the production of Aβ1-42 peptides (Aβ42) and on the expressed genes in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were explored |

|

| 2012 | [82] |

| Investigation of CA’s impact on the apoptosis induced by A42 or A43 peptides in cultured SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells |

|

| 2014 | [83] |

| This study investigated the effects of CA on NLRP3 activation using in in vitro and in vivo experiments |

|

| 2023 | [120] |

| This study compared the phytochemical content and the biological properties of R. officinalis samples |

|

| 2013 | [80] |

| The impact of carnosol on rotenone-induced neurotoxicity in cultured SN4741 dopaminergic cells was studied |

|

| 2006 | [11] |

| The effect of eugenol in a mouse model induced with MPTP was studied |

|

| 2022 | [103] |

| The effect of eugenol along with levodopa in 6-OHDA-stimulated Wistar rats was studied |

|

| 2020 | [104] |

| The efficacy of eugenol on AD pathologies was explored using a 5X familiar AD mouse model (5XFAD) |

|

| 2023 | [111] |

| This study assessed the effect of eugenol on the amyloid plaques present in AD rat models |

|

| 2019 | [112] |

| This study aimed to explore the anti-amnesic effect of eugenol in scopolamine-treated AD rodents |

|

| 2019 | [113] |

| The activity of luteolin in 6-OHDA-treated PC12 cells |

|

| 2014 | [105] |

| Effect of 1,8 cineole and a-pinene as neuroprotective in H2O2-treated cells |

|

| 2016 | [107] |

| The potent pharmacological connection between 1,8-cineole, mood, and cognitive performance after exposure to R. officinalis aroma was assessed |

|

| 2012 | [118] |

| This study experimented on AGE-induced neuronal injury and intracerebroventricular AGE animals, as candidate AD models. Additionally, the impact of CIN on AD and the mechanisms both in vitro and in vivo were also investigated |

|

| 2022 | [110] |

| RA isolated from an R. officinalis extract and EO was evaluated for its AChE and BChE inhibition activity |

|

| 2007 | [90] |

| UA’s effect on rotenone-treated rats was studied |

|

| 2020 | [108] |

| Camphor’s ability to treat depression in rats was studied |

|

| 2021 | [123] |

| The study assessed the potency of different diterpenes that were isolated from rosemary to function as AChE inhibitors |

|

| 2024 | [109] |

3.9. Rosemary Extracts and EOs for Treating NDs

4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Therapeutic Effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and Its Active Constituents on Nervous System Disorders. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 23, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Mansinhos, I.; Romano, A. Aromatic Plants: A Source of Compounds with Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Effects. In Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants in Neurological Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 155–173. ISBN 978-0-12-817780-8. [Google Scholar]

- Güneş, A.; Kordali, Ş.; Turan, M.; Usanmaz Bozhüyük, A. Determination of Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Phenolic Contents of Some Species of the Asteraceae Family from Medicanal Plants. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 137, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Camargo, A.D.P.; Herrero, M. Rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis) as a Functional Ingredient: Recent Scientific Evidence. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 14, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulou, S.D.; Androutsopoulou, C.; Hahalis, P.; Kotsalou, C.; Vantarakis, A.; Lamari, F.N. Rosemary Extract and Essential Oil as Drink Ingredients: An Evaluation of Their Chemical Composition, Genotoxicity, Antimicrobial, Antiviral, and Antioxidant Properties. Foods 2021, 10, 3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafie, H.; Soheila, H.; Grant, E. Rosmarinus officinalis (Rosemary): A Novel Therapeutic Agent for Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anticancer, Antidiabetic, Antidepressant, Neuroprotective, Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Obesity Treatment. Herb. Med. Open Access 2017, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aziz, E.; Batool, R.; Akhtar, W.; Shahzad, T.; Malik, A.; Shah, M.A.; Iqbal, S.; Rauf, A.; Zengin, G.; Bouyahya, A.; et al. Rosemary Species: A Review of Phytochemicals, Bioactivities and Industrial Applications. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 151, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, J.R.; Camargo, S.E.A.; De Oliveira, L.D. Rosmarinus officinalis L. (Rosemary) as Therapeutic and Prophylactic Agent. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, H.; Jiang, H.; Du, X.; Sun, P.; Xie, J. Neurorescue Effect of Rosmarinic Acid on 6-Hydroxydopamine-Lesioned Nigral Dopamine Neurons in Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2012, 47, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-R.; Tsai, C.-W.; Chang, S.-W.; Lin, C.-Y.; Huang, L.-C.; Tsai, C.-W. Carnosic Acid Protects against 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Neurotoxicity in in Vivo and in Vitro Model of Parkinson’s Disease: Involvement of Antioxidative Enzymes Induction. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 225, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-J.; Kim, J.-S.; Cho, H.-S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.-Y.; Chun, H.S. Carnosol, a Component of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Protects Nigral Dopaminergic Neuronal Cells. NeuroReport 2006, 17, 1729–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taram, F.; Ignowski, E.; Duval, N.; Linseman, D. Neuroprotection Comparison of Rosmarinic Acid and Carnosic Acid in Primary Cultures of Cerebellar Granule Neurons. Molecules 2018, 23, 2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Cho, H.-S.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, C.-S.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, S.-J.; Chun, H.S. Rosmarinic Acid Protects Human Dopaminergic Neuronal Cells against Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Apoptosis. Toxicology 2008, 250, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.R. The Dietary Components Carnosic Acid and Carnosol as Neuroprotective Agents: A Mechanistic View. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6155–6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-H.; Ou, H.-P.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, F.-J.; Wu, C.-R.; Chang, S.-W.; Tsai, C.-W. Carnosic Acid Prevents 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Cell Death in SH-SY5Y Cells via Mediation of Glutathione Synthesis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 1893–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Tsai, C.-W.; Tsai, C.-W. Carnosic Acid Protects SH-SY5Y Cells against 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Cell Death through Upregulation of Parkin Pathway. Neuropharmacology 2016, 110, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.R.; Ferreira, G.C.; Schuck, P.F. Protective Effect of Carnosic Acid against Paraquat-Induced Redox Impairment and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in SH-SY5Y Cells: Role for PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 Pathway. Toxicol. In Vitro 2016, 32, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhouibi, N.; Manuguerra, S.; Arena, R.; Messina, C.M.; Santulli, A.; Kacem, S.; Dhaouadi, H.; Mahdhi, A. Impact of the Extraction Method on the Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Potency of Rosmarinus officinalis L. Extracts. Metabolites 2023, 13, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leri, M.; Scuto, M.; Ontario, M.L.; Calabrese, V.; Calabrese, E.J.; Bucciantini, M.; Stefani, M. Healthy Effects of Plant Polyphenols: Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Xia, Y.; Peng, C.; Li, C. Research and Application Progress of Radiomics in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Meta-Radiol. 2024, 2, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R. What Causes Neurodegenerative Disease? Folia Neuropathol. 2020, 58, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasikumar, D.S.N.; Thiruselvam, P.; Sundararajan, V.; Ravindran, R.; Gunasekaran, S.; Madathil, D.; Kaliamurthi, S.; Peslherbe, G.H.; Selvaraj, G.; Sudhakaran, S.L. Insights into Dietary Phytochemicals Targeting Parkinson’s Disease Key Genes and Pathways: A Network Pharmacology Approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 172, 108195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eser, P.; Kocabicak, E.; Bekar, A.; Temel, Y. The Interplay between Neuroinflammatory Pathways and Parkinson’s Disease. Exp. Neurol. 2024, 372, 114644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, R.; Maier, O. Interrelation of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Neurodegenerative Disease: Role of TNF. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 610813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzilay, J.I.; Abraham, L.; Heckbert, S.R.; Cushman, M.; Kuller, L.H.; Resnick, H.E.; Tracy, R.P. The Relation of Markers of Inflammation to the Development of Glucose Disorders in the Elderly. Diabetes 2001, 50, 2384–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, A.D. C-Reactive Protein, Interleukin 6, and Risk of Developing Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA 2001, 286, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zandi, P.P.; Anthony, J.C.; Hayden, K.M.; Mehta, K.; Mayer, L.; Breitner, J.C.S. Reduced Incidence of AD with NSAID but Not H 2 Receptor Antagonists: The Cache County Study. Neurology 2002, 59, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, J.; Yadav, S.K.; Chouhan, S.; Singh, S.P. Neuroprotective Role of Withania Somnifera Root Extract in Maneb–Paraquat Induced Mouse Model of Parkinsonism. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, A.; Yasser, M.; Ahmad, A.; Natsir, H.; Wahab, A.W.; Taba, P.; Pratama, I.; Rajab, A.; Abubakar, A.N.F.; Putri, T.W.; et al. A Review: Progress and Trend Advantage of Dopamine Electrochemical Sensor. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2024, 959, 118157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson Disease. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/parkinson-disease (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Singla, R.K.; Agarwal, T.; He, X.; Shen, B. Herbal Resources to Combat a Progressive & Degenerative Nervous System Disorder- Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Drug Targets 2021, 22, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Peana, M.; Maes, M.; Dadar, M.; Severin, B. The Glutathione System in Parkinson’s Disease and Its Progression. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 120, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, T.; Deore, S.L.; Kide, A.A.; Shende, B.A.; Sharma, R.; Dadarao Chakole, R.; Nemade, L.S.; Kishor Kale, N.; Borah, S.; Shrikant Deokar, S.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease, and Parkinson’s Disease, Huntington’s Disease and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis—An Updated Review. Mitochondrion 2023, 71, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.Y.; Nam, M.-H.; Yoon, H.H.; Kim, J.; Hwang, Y.J.; Won, W.; Woo, D.H.; Lee, J.A.; Park, H.-J.; Jo, S.; et al. Aberrant Tonic Inhibition of Dopaminergic Neuronal Activity Causes Motor Symptoms in Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 276–291.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite Silva, A.B.R.; Gonçalves De Oliveira, R.W.; Diógenes, G.P.; De Castro Aguiar, M.F.; Sallem, C.C.; Lima, M.P.P.; De Albuquerque Filho, L.B.; Peixoto De Medeiros, S.D.; Penido De Mendonça, L.L.; De Santiago Filho, P.C.; et al. Premotor, Nonmotor and Motor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease: A New Clinical State of the Art. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 84, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh Yazd, S.A.; Gashtil, S.; Moradpoor, M.; Pishdar, S.; Nabian, P.; Kazemi, Z.; Naeim, M. Reducing Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: The Effectiveness of Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Park. Relat. Disord. 2023, 112, 105456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Sun, M.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Yan, M. The Delivery of Tyrosine Hydroxylase Accelerates the Neurorestoration of Macaca Rhesus Model of Parkinson’s Disease Provided by Neurturin. Neurosci. Lett. 2012, 524, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, J.; Machado, M.; Dias-Teixeira, M.; Ferraz, R.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Grosso, C. The Neuroprotective Effect of Traditional Chinese Medicinal Plants—A Critical Review. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 3208–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, P.; Nagashanmugam, K.B.; Priyatharshni, S.; Lavanya, R.; Prabhu, N.; Ponnusamy, S. Review on the Interactions between Dopamine Metabolites and α-Synuclein in Causing Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochem. Int. 2023, 162, 105461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.R. Carnosic Acid and Carnosol: Neuroprotection and the Mitochondria. In Oxidative Stress and Dietary Antioxidants in Neurological Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 217–230. ISBN 978-0-12-817780-8. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens Keun, J.T.; Arnoldussen, I.A.; Vriend, C.; van de Rest, O. Dietary Approaches to Improve Efficacy and Control Side Effects of Levodopa Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 2265–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridzadeh, A.; Salimi, Y.; Ghasemirad, H.; Kargar, M.; Rashtchian, A.; Mahmoudvand, G.; Karimi, M.A.; Zerangian, N.; Jahani, N.; Masoudi, A.; et al. Neuroprotective Potential of Aromatic Herbs: Rosemary, Sage, and Lavender. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 909833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.B.; Stacy, M.A. What’s in the Pipeline for the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2008, 8, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltynie, T.; Bruno, V.; Fox, S.; Kühn, A.A.; Lindop, F.; Lees, A.J. Medical, Surgical, and Physical Treatments for Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet 2024, 403, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Zhang, X.; Su, Y.; Chan, P.; Xu, E. Effects of Different Levodopa Doses on Blood Pressure in Older Patients with Early and Middle Stages of Parkinson’s Disease. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akushevich, I.; Yashkin, A.; Kovtun, M.; Kravchenko, J.; Arbeev, K.; Yashin, A.I. Forecasting Prevalence and Mortality of Alzheimer’s Disease Using the Partitioning Models. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 174, 112133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, K.; Grundke-Iqbal, I. Alzheimer’s Disease, a Multifactorial Disorder Seeking Multitherapies. Alzheimers Dement. 2010, 6, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.A.; Targowska-Duda, K.; Klimek, K.; Ginalska, G.; Jóźwiak, K.; Waksmundzka-Hajnos, M.; Cieśla, Ł. Volatile Terpenoids as Potential Drug Leads in Alzheimer’s Disease. Open Chem. 2017, 15, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobley, J.N.; Fiorello, M.L.; Bailey, D.M. 13 Reasons Why the Brain Is Susceptible to Oxidative Stress. Redox Biol. 2018, 15, 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raefsky, S.M.; Furman, R.; Milne, G.; Pollock, E.; Axelsen, P.; Mattson, M.P.; Shchepinov, M.S. Deuterated Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Reduce Brain Lipid Peroxidation and Hippocampal Amyloid β-Peptide Levels, without Discernable Behavioral Effects in an APP/PS1 Mutant Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2018, 66, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Mattson, M.P. Apolipoprotein E and Oxidative Stress in Brain with Relevance to Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 138, 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramassamy, C.; Krzywkowski, P.; Averill, D.; Lussier-Cacan, S.; Theroux, L.; Christen, Y.; Davignon, J.; Poirier, J. Impact of apoE Deficiency on Oxidative Insults and Antioxidant Levels in the Brain. Mol. Brain Res. 2001, 86, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterbauer, H.; Schaur, R.J.; Zollner, H. Chemistry and Biochemistry of 4-Hydroxynonenal, Malonaldehyde and Related Aldehydes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991, 11, 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caberlotto, L.; Marchetti, L.; Lauria, M.; Scotti, M.; Parolo, S. Integration of Transcriptomic and Genomic Data Suggests Candidate Mechanisms for APOE4-Mediated Pathogenic Action in Alzheimer’s Disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Domenico, F.; Tramutola, A.; Barone, E.; Lanzillotta, C.; Defever, O.; Arena, A.; Zuliani, I.; Foppoli, C.; Iavarone, F.; Vincenzoni, F.; et al. Restoration of Aberrant mTOR Signaling by Intranasal Rapamycin Reduces Oxidative Damage: Focus on HNE-Modified Proteins in a Mouse Model of down Syndrome. Redox Biol. 2019, 23, 101162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Ma, T.R.; Miranda, R.D.; Balestra, M.E.; Mahley, R.W.; Huang, Y. Lipid- and Receptor-Binding Regions of Apolipoprotein E4 Fragments Act in Concert to Cause Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 18694–18699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Reed, T.; Perluigi, M.; De Marco, C.; Coccia, R.; Cini, C.; Sultana, R. Elevated Protein-Bound Levels of the Lipid Peroxidation Product, 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal, in Brain from Persons with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 397, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fišar, Z.; Hansíková, H.; Křížová, J.; Jirák, R.; Kitzlerová, E.; Zvěřová, M.; Hroudová, J.; Wenchich, L.; Zeman, J.; Raboch, J. Activities of Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Complexes in Platelets of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Depressive Disorder. Mitochondrion 2019, 48, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, M.; Beal, M.F. Neuroprotective Strategies Involving ROS in Alzheimer Disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckert, A.; Schulz, K.L.; Rhein, V.; Götz, J. Convergence of Amyloid-β and Tau Pathologies on Mitochondria In Vivo. Mol. Neurobiol. 2010, 41, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhein, V.; Song, X.; Wiesner, A.; Ittner, L.M.; Baysang, G.; Meier, F.; Ozmen, L.; Bluethmann, H.; Dröse, S.; Brandt, U.; et al. Amyloid-β and Tau Synergistically Impair the Oxidative Phosphorylation System in Triple Transgenic Alzheimer’s Disease Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20057–20062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Lee, G.; Nahed, P.; Kambar, M.E.Z.N.; Zhong, K.; Fonseca, J.; Taghva, K. Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Development Pipeline: 2022. Alzheimers Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2022, 8, e12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Chu, F.; Zhu, F.; Zhu, J. Impact of Anti-Amyloid-β Monoclonal Antibodies on the Pathology and Clinical Profile of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Focus on Aducanumab and Lecanemab. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 870517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamaraj, C.; Ragavendran, C.; Kumar, R.C.S.; Ali, A.; Khan, S.U.; ur-Rehman Mashwani, Z.; Luna-Arias, J.P.; Pedroza, J.P.R. Antiparasitic Potential of Asteraceae Plants: A Comprehensive Review on Therapeutic and Mechanistic Aspects for Biocompatible Drug Discovery. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Lu, Y.; Xie, M.; Tang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, G.; Wang, H. Antimicrobial Activity in Asterceae: The Selected Genera Characterization and against Multidrug Resistance Bacteria. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhaogao, L.; Yaxuan, W.; Mengwei, X.; Haiyu, L.; Lin, L.; Delin, X. Molecular Mechanism Overview of Metabolite Biosynthesis in Medicinal Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 204, 108125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizani, R.S.; Viganó, J.; De Souza Mesquita, L.M.; Contieri, L.S.; Sanches, V.L.; Chaves, J.O.; Souza, M.C.; Da Silva, L.C.; Rostagno, M.A. Beyond Aroma: A Review on Advanced Extraction Processes from Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) and Sage (Salvia Officinalis) to Produce Phenolic Acids and Diterpenes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustaiyan, A.; Faridchehr, A. Constituents and Biological Activities of Selected Genera of the Iranian Asteraceae Family. J. Herb. Med. 2021, 25, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuchi, C.G.; Morya, S. Herbs of Asteraceae Family: Nutritional Profile, Bioactive Compounds, and Potentials in Therapeutics. In Harvesting Food from Weeds; Gupta, P., Chhikara, N., Panghal, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 21–78. ISBN 978-1-119-79197-3. [Google Scholar]

- Hechaichi, F.Z.; Bendif, H.; Bensouici, C.; Alsalamah, S.A.; Zaidi, B.; Bouhenna, M.M.; Souilah, N.; Alghonaim, M.I.; Benslama, A.; Medjekal, S.; et al. Phytochemicals, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Potentials and LC-MS Analysis of Centaurea Parviflora Desf. Extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, A.N.M. Pharmacognostical Botany: Classification of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (MAPs), Botanical Taxonomy, Morphology, and Anatomy of Drug Plants. In Therapeutic Use of Medicinal Plants and Their Extracts: Volume 1; Progress in Drug Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 73, pp. 177–293. ISBN 978-3-319-63861-4. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Goksen, G.; Zhang, W. Rosemary Essential Oil: Chemical and Biological Properties, with Emphasis on Its Delivery Systems for Food Preservation. Food Control 2023, 154, 110003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz Do Nascimento, L.; Moraes, A.A.B.D.; Costa, K.S.D.; Pereira Galúcio, J.M.; Taube, P.S.; Costa, C.M.L.; Neves Cruz, J.; De Aguiar Andrade, E.H.; Faria, L.J.G.D. Bioactive Natural Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils from Spice Plants: New Findings and Potential Applications. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, N.A.; Attan, N.; Wahab, R.A. An Overview of Cosmeceutically Relevant Plant Extracts and Strategies for Extraction of Plant-Based Bioactive Compounds. Food Bioprod. Process. 2018, 112, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kola, A.; Hecel, A.; Lamponi, S.; Valensin, D. Novel Perspective on Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment: Rosmarinic Acid Molecular Interplay with Copper(II) and Amyloid β. Life 2020, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagianni, K.; Pettas, S.; Kanata, E.; Lioulia, E.; Thune, K.; Schmitz, M.; Tsamesidis, I.; Lymperaki, E.; Xanthopoulos, K.; Sklaviadis, T.; et al. Carnosic Acid and Carnosol Display Antioxidant and Anti-Prion Properties in In Vitro and Cell-Free Models of Prion Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, C.; Rebocho, S.; Craveiro, R.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C. Selective Extraction and Stabilization of Bioactive Compounds from Rosemary Leaves Using a Biphasic NADES. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 954835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Tsai, C.-W. Carnosic Acid Attenuates 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Cells by Inducing Autophagy Through an Enhanced Interaction of Parkin and Beclin1. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 2813–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jemia, M.B.; Tundis, R.; Maggio, A.; Rosselli, S.; Senatore, F.; Menichini, F.; Bruno, M.; Kchouk, M.E.; Loizzo, M.R. NMR-Based Quantification of Rosmarinic and Carnosic Acids, GC–MS Profile and Bioactivity Relevant to Neurodegenerative Disorders of Rosmarinus officinalis L. Extracts. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, M.R.; Ferreira, G.C.; Schuck, P.F.; Dal Bosco, S.M. Role for the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in the Protective Effects of Carnosic Acid against Methylglyoxal-Induced Neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 242, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, P.; Yoshida, H.; Matsumiya, T.; Imaizumi, T.; Tanji, K.; Xing, F.; Hayakari, R.; Dempoya, J.; Tatsuta, T.; Aizawa-Yashiro, T.; et al. Carnosic Acid Suppresses the Production of Amyloid-β 1–42 by Inducing the Metalloprotease Gene TACE/ADAM17 in SH-SY5Y Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Neurosci. Res. 2013, 75, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, P.; Yoshida, H.; Tanji, K.; Matsumiya, T.; Xing, F.; Hayakari, R.; Wang, L.; Tsuruga, K.; Tanaka, H.; Mimura, J.; et al. Carnosic Acid Attenuates Apoptosis Induced by Amyloid-β 1–42 or 1–43 in SH-SY5Y Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Neurosci. Res. 2015, 94, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, T.; Trudler, D.; Oh, C.-K.; Lipton, S.A. Potential Therapeutic Use of the Rosemary Diterpene Carnosic Acid for Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Long-COVID through NRF2 Activation to Counteract the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, S.A.; Rezaie, T.; Nutter, A.; Lopez, K.M.; Parker, J.; Kosaka, K.; Satoh, T.; McKercher, S.R.; Masliah, E.; Nakanishi, N. Therapeutic Advantage of Pro-Electrophilic Drugs to Activate the Nrf2/ARE Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease Models. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, N.; Rasoolijazi, H.; Joghataie, M.T.; Soleimani, S. Neuroprotective Effects of Carnosic Acid in an Experimental Model of Alzheimer’s Disease in Rats. Cell J. 2011, 13, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rasoolijazi, H.; Azad, N.; Joghataei, M.T.; Kerdari, M.; Nikbakht, F.; Soleimani, M. The Protective Role of Carnosic Acid against Beta-Amyloid Toxicity in Rats. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 917082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, H.; Venkataramana, M.; Jalali Ghassam, B.; Chandra Nayaka, S.; Nataraju, A.; Geetha, N.P.; Prakash, H.S. Rosmarinic Acid Mediated Neuroprotective Effects against H2O2-Induced Neuronal Cell Damage in N2A Cells. Life Sci. 2014, 113, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senol, F.S.; Ślusarczyk, S.; Matkowski, A.; Pérez-Garrido, A.; Girón-Rodríguez, F.; Cerón-Carrasco, J.P.; den-Haan, H.; Peña-García, J.; Pérez-Sánchez, H.; Domaradzki, K.; et al. Selective in Vitro and in Silico Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitory Activity of Diterpenes and Rosmarinic Acid Isolated from Perovskia atriplicifolia Benth. and Salvia glutinosa L. Phytochemistry 2017, 133, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhan, I.; Aslan, S.; Kartal, M.; Şener, B.; Hüsnü Can Başer, K. Inhibitory Effect of Turkish Rosmarinus officinalis L. on Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase Enzymes. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DemiRezer, L.Ö.; Gürbüz, P.; KeliCen Uğur, E.P.; Bodur, M.; Özenver, N.; Uz, A.; Güvenalp, Z. Molecular Docking and Ex Vivo and in Vitro Anticholinesterase Activity Studies of Salvia Sp. and Highlighted Rosmarinic Acid. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 45, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szwajgier, D. Anticholinesterase Activity of Selected Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids–Interaction Testing in Model Solutions. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2015, 22, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, R.; Hatayama, K.; Takahashi, T.; Hayashi, T.; Sato, Y.; Sato, D.; Ohta, K.; Nakano, H.; Seki, C.; Endo, Y.; et al. Structure–Activity Relations of Rosmarinic Acid Derivatives for the Amyloid β Aggregation Inhibition and Antioxidant Properties. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 138, 1066–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornejo, A.; Aguilar Sandoval, F.; Caballero, L.; Machuca, L.; Muñoz, P.; Caballero, J.; Perry, G.; Ardiles, A.; Areche, C.; Melo, F. Rosmarinic Acid Prevents Fibrillization and Diminishes Vibrational Modes Associated to β Sheet in Tau Protein Linked to Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuvone, T.; De Filippis, D.; Esposito, G.; D’Amico, A.; Izzo, A.A. The Spice Sage and Its Active Ingredient Rosmarinic Acid Protect PC12 Cells from Amyloid-β Peptide-Induced Neurotoxicity. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 317, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presti-Silva, S.M.; Herlinger, A.L.; Martins-Silva, C.; Pires, R.G.W. Biochemical and Behavioral Effects of Rosmarinic Acid Treatment in an Animal Model of Parkinson’s Disease Induced by MPTP. Behav. Brain Res. 2023, 440, 114257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantar Gok, D.; Hidisoglu, E.; Ocak, G.A.; Er, H.; Acun, A.D.; Yargıcoglu, P. Protective Role of Rosmarinic Acid on Amyloid Beta 42-Induced Echoic Memory Decline: Implication of Oxidative Stress and Cholinergic Impairment. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 118, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.Y.; Hwang, B.R.; Lee, M.H.; Lee, S.; Cho, E.J. Perilla frutescens Var. Japonica and Rosmarinic Acid Improve Amyloid-β 25-35 Induced Impairment of Cognition and Memory Function. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2016, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkam, T.; Nitta, A.; Mizoguchi, H.; Itoh, A.; Nabeshima, T. A Natural Scavenger of Peroxynitrites, Rosmarinic Acid, Protects against Impairment of Memory Induced by Aβ25–35. Behav. Brain Res. 2007, 180, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantar Gok, D.; Ozturk, N.; Er, H.; Aslan, M.; Demir, N.; Derin, N.; Agar, A.; Yargicoglu, P. Effects of Rosmarinic Acid on Cognitive and Biochemical Alterations in Ovariectomized Rats Treated with D-Galactose. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2016, 53, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Wang, D.-D.; Xu, Y.-X.; Wang, C.; Cao, L.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zhu, C.-Q. Aging as a Precipitating Factor in Chronic Restraint Stress-Induced Tau Aggregation Pathology, and the Protective Effects of Rosmarinic Acid. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 49, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavan, B.; Bianchi, A.; Botti, G.; Ferraro, L.; Valerii, M.C.; Spisni, E.; Dalpiaz, A. Pharmacokinetic and Permeation Studies in Rat Brain of Natural Compounds Led to Investigate Eugenol as Direct Activator of Dopamine Release in PC12 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vora, U.; Vyas, V.K.; Wal, P.; Saxena, B. Effects of Eugenol on the Behavioral and Pathological Progression in the MPTP-Induced Parkinson’s Disease Mouse Model. Drug Discov. Ther. 2022, 16, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira Vasconcelos, C.F.; Da Cunha Ferreira, N.M.; Hardy Lima Pontes, N.; De Sousa Dos Reis, T.D.; Basto Souza, R.; Aragão Catunda Junior, F.E.; Vasconcelos Aguiar, L.M.; Maranguape Silva Da Cunha, R. Eugenol and Its Association with Levodopa in 6-hydroxydopamine-induced Hemiparkinsonian Rats: Behavioural and Neurochemical Alterations. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 127, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-W.; Yen, J.-H.; Shen, Y.-T.; Wu, K.-Y.; Wu, M.-J. Luteolin Modulates 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Transcriptional Changes of Stress Response Pathways in PC12 Cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Chen, Z.; Yang, L.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Q.; Huang, F.; Wu, X. Luteolin-7-O-Glucoside Protects Dopaminergic Neurons by Activating Estrogen-Receptor-Mediated Signaling Pathway in MPTP-Induced Mice. Toxicology 2019, 426, 152256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porres-Martínez, M.; González-Burgos, E.; Carretero, M.E.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. In Vitro Neuroprotective Potential of the Monoterpenes α-Pinene and 1,8-Cineole against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in PC12 Cells. Z. Naturforschung C 2016, 71, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshattiwar, V.; Muke, S.; Kaikini, A.; Bagle, S.; Dighe, V.; Sathaye, S. Mechanistic Evaluation of Ursolic Acid against Rotenone Induced Parkinson’s Disease–Emphasizing the Role of Mitochondrial Biogenesis. Brain Res. Bull. 2020, 160, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaoui, Z.; Merzouki, M.; Oualdi, I.; Bitari, A.; Oussaid, A.; Challioui, A.; Touzani, R.; Hammouti, B.; Agerico Diño, W. Alzheimer’s Disease: In Silico Study of Rosemary Diterpenes Activities. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 6, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.; Bai, Y.; Xuan, X.; Bian, M.; Zhang, G.; Wei, C. 1,8-Cineole Ameliorates Advanced Glycation End Products-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease-like Pathology In Vitro and In Vivo. Molecules 2022, 27, 3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.-J.; Kim, N.; Jeon, S.H.; Gee, M.S.; Kim, J.-W.; Lee, J.K. Eugenol Relieves the Pathological Manifestations of Alzheimer’s Disease in 5×FAD Mice. Phytomedicine 2023, 118, 154930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, P.; Yaghmaei, P.; Tehrani, H.S.; Ebrahim-Habibi, A. Effects of Eugenol on Alzheimer’s Disease-like Manifestations in Insulin- and Aβ-Induced Rat Models. Neurophysiology 2019, 51, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabadu, D.; Sharma, M. Eugenol Attenuates Scopolamine-Induced Hippocampal Cholinergic, Glutamatergic, and Mitochondrial Toxicity in Experimental Rats. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V.R.; Vieira, C.G.; De Souza, L.P.; Moysés, F.; Basso, C.; Papke, D.K.M.; Pires, T.R.; Siqueira, I.R.; Picada, J.N.; Pereira, P. Antiepileptogenic, Antioxidant and Genotoxic Evaluation of Rosmarinic Acid and Its Metabolite Caffeic Acid in Mice. Life Sci. 2015, 122, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, A.-J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Tao, B.-Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.-F.; Zhou, D.-B. Spinal Cord Injury Effectively Ameliorated by Neuroprotective Effects of Rosmarinic Acid. Nutr. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzi, A.; Babaei Zarch, M.; Nazari, Z.; Azemi, M.E. Effect of Essential Oil of Leaf and Aerial Part of Rosmarinus officinalis on Passive Avoidance Memory in Aged and Young Mice. Jundishapur Sci. Med. J. 2014, 13, 503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Filiptsova, O.V.; Gazzavi-Rogozina, L.V.; Timoshyna, I.A.; Naboka, O.I.; Dyomina, Y.V.; Ochkur, A.V. The Effect of the Essential Oils of Lavender and Rosemary on the Human Short-Term Memory. Alex. J. Med. 2018, 54, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, M.; Oliver, L. Plasma 1,8-Cineole Correlates with Cognitive Performance Following Exposure to Rosemary Essential Oil Aroma. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 2, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, M.; Cook, J.; Wesnes, K.; Duckett, P. Aromas of Rosemary and Lavender Essential Oils Differentially Affect Cognition and Mood in Healthy Adults. Int. J. Neurosci. 2003, 113, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Li, N.; Li, D.; Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Ouyang, W. Carnosic Acid Inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Targeting Both Priming and Assembly Steps. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 116, 109819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, H.; Saito, T.; Okamura, N.; Yagi, A. Inhibition of Lipid Peroxidation and Superoxide Generation by Diterpenoids from Rosmarinus officinalis. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, S.A.; Niehoff, M.L.; Ceddia, M.A.; Herrlinger, K.A.; Lewis, B.J.; Feng, S.; Welleford, A.; Butterfield, D.A.; Morley, J.E. Effect of Botanical Extracts Containing Carnosic Acid or Rosmarinic Acid on Learning and Memory in SAMP8 Mice. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 165, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.; Mahmoud, H.A.-A.; Kandeil, M.A.; Khalaf, M.M. Neuroprotective Role of Camphor against Ciprofloxacin Induced Depression in Rats: Modulation of Nrf-2 and TLR4. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2021, 43, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Ahn, M.; Kim, J.; Moon, C.; Matsuda, H.; Tanaka, A.; Nomura, Y.; Jung, K.; Shin, T. Eugenol Alleviates the Symptoms of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in Mice by Suppressing Inflammatory Responses. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 128, 111479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriem, K.M.M.; El-Soury, N.H.T. Luteolin Amends Neural Neurotransmitters, Antioxidants, and Inflammatory Markers in the Cerebral Cortex of Adderall Exposed Rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2024, 823, 137652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, B.; Almarzooqi, S.; Raj, V.; Bhongade, B.A.; Patil, R.B.; Subramanian, V.S.; Attoub, S.; Rizvi, T.A.; Adrian, T.E.; Subramanya, S.B. Molecular Docking Identifies 1,8-Cineole (Eucalyptol) as A Novel PPARγ Agonist That Alleviates Colon Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, F.J.; Amber, S.; Sumera; Hassan, D.; Ahmed, T.; Zahid, S. Rosmarinic Acid and Ursolic Acid Alleviate Deficits in Cognition, Synaptic Regulation and Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in an Aβ1-42-Induced Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Phytomedicine 2021, 83, 153490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajizadeh Moghaddam, A.; Malekzadeh Estalkhi, F.; Khanjani Jelodar, S.; Ahmed Hasan, T.; Farhadi-Pahnedari, S.; Karimian, M. Neuroprotective Effects of Alpha-Pinene against Behavioral Deficits in Ketamine-Induced Mice Model of Schizophrenia: Focusing on Oxidative Stress Status. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2024, 16, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-E.; Kim, S.; Sapkota, K.; Kim, S.-J. Neuroprotective Effect of Rosmarinus officinalis Extract on Human Dopaminergic Cell Line, SH-SY5Y. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2010, 30, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satou, T.; Hanashima, Y.; Mizutani, I.; Koike, K. The Effect of Inhalation of Essential Oil from Rosmarinus officinalis on Scopolamine-induced Alzheimer’s Type Dementia Model Mice. Flavour Fragr. J. 2018, 33, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimbo, D.; Kimura, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Inoue, M.; Urakami, K. Effect of Aromatherapy on Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Psychogeriatrics 2009, 9, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, N.S.L.; Menzies, R.; Hodgson, F.; Wedgewood, P.; Howes, M.-J.R.; Brooker, H.J.; Wesnes, K.A.; Perry, E.K. A Randomised Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Pilot Trial of a Combined Extract of Sage, Rosemary and Melissa, Traditional Herbal Medicines, on the Enhancement of Memory in Normal Healthy Subjects, Including Influence of Age. Phytomedicine 2018, 39, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Qiao, O.; Ji, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; et al. Rosmarinic Acid Potentiates and Detoxifies Tacrine in Combination for Alzheimer’s Disease. Phytomedicine 2023, 109, 154600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayashima, T.; Matsubara, K. Antiangiogenic Effect of Carnosic Acid and Carnosol, Neuroprotective Compounds in Rosemary Leaves. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoupras, A.; Ni, V.L.J.; O’Mahony, É.; Karali, M. Winemaking: “With One Stone, Two Birds”? A Holistic Review of the Bio-Functional Compounds, Applications and Health Benefits of Wine and Wineries’ By-Products. Fermentation 2023, 9, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damianova, S.; Tasheva, S.; Stoyanova, A.; Damianov, D. Investigation of Extracts from Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) for Application in Cosmetics. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2010, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachel, F.N.S.; Schuh, R.S.; Veras, K.S.; Bassani, V.L.; Koester, L.S.; Henriques, A.T.; Braganhol, E.; Teixeira, H.F. An Overview of the Neuroprotective Potential of Rosmarinic Acid and Its Association with Nanotechnology-Based Delivery Systems: A Novel Approach to Treating Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 122, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-G.; Cho, K.-M.; Lee, C.-K.; Yoo, I.-D. Terreulactone A, a Novel Meroterpenoid with Anti-Acetylcholinesterase Activity from Aspergillus Terreus. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 3197–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosmopoulou, D.; Lafara, M.-P.; Adamantidi, T.; Ofrydopoulou, A.; Grabrucker, A.M.; Tsoupras, A. Neuroprotective Benefits of Rosmarinus officinalis and Its Bioactives against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6417. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156417

Kosmopoulou D, Lafara M-P, Adamantidi T, Ofrydopoulou A, Grabrucker AM, Tsoupras A. Neuroprotective Benefits of Rosmarinus officinalis and Its Bioactives against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(15):6417. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156417

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosmopoulou, Danai, Maria-Parthena Lafara, Theodora Adamantidi, Anna Ofrydopoulou, Andreas M. Grabrucker, and Alexandros Tsoupras. 2024. "Neuroprotective Benefits of Rosmarinus officinalis and Its Bioactives against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases" Applied Sciences 14, no. 15: 6417. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156417

APA StyleKosmopoulou, D., Lafara, M.-P., Adamantidi, T., Ofrydopoulou, A., Grabrucker, A. M., & Tsoupras, A. (2024). Neuroprotective Benefits of Rosmarinus officinalis and Its Bioactives against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Applied Sciences, 14(15), 6417. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14156417