XGBoost-Enhanced Graph Neural Networks: A New Architecture for Heterogeneous Tabular Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

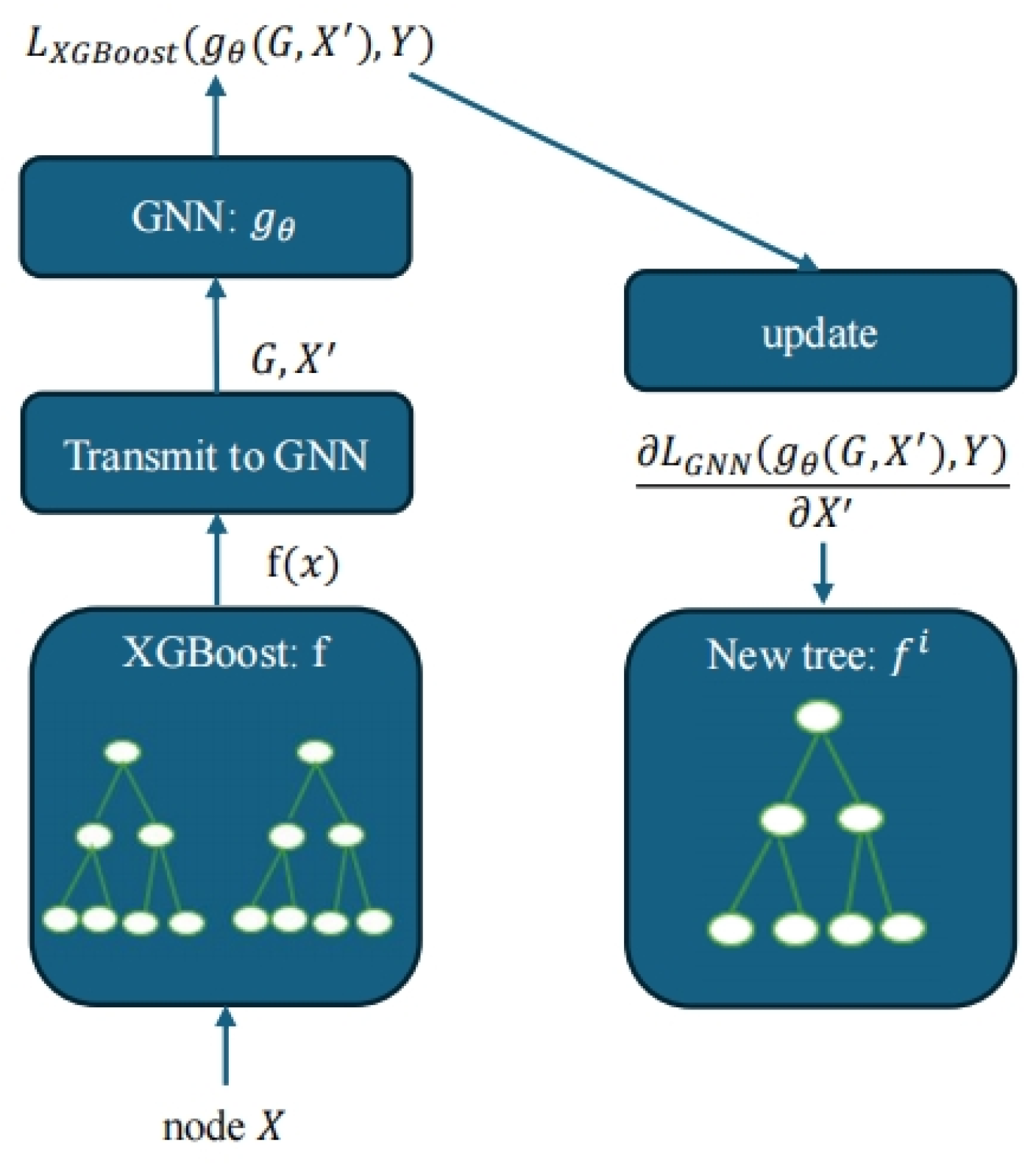

- We introduce XGNN, a graph neural network model for tabular data, to jointly train the XGBoost and GNN models. We believe this is the first time we have jointly studied these two models in the field of tabular data.

- (2)

- The dataset types chosen in this paper are rich, including heterogeneous datasets, isomorphic datasets, sparse datasets, and bag-of-words datasets, which are involved in binary classification and multi-classification problems. We simultaneously achieve good results in both node prediction and node classification tasks.

- (3)

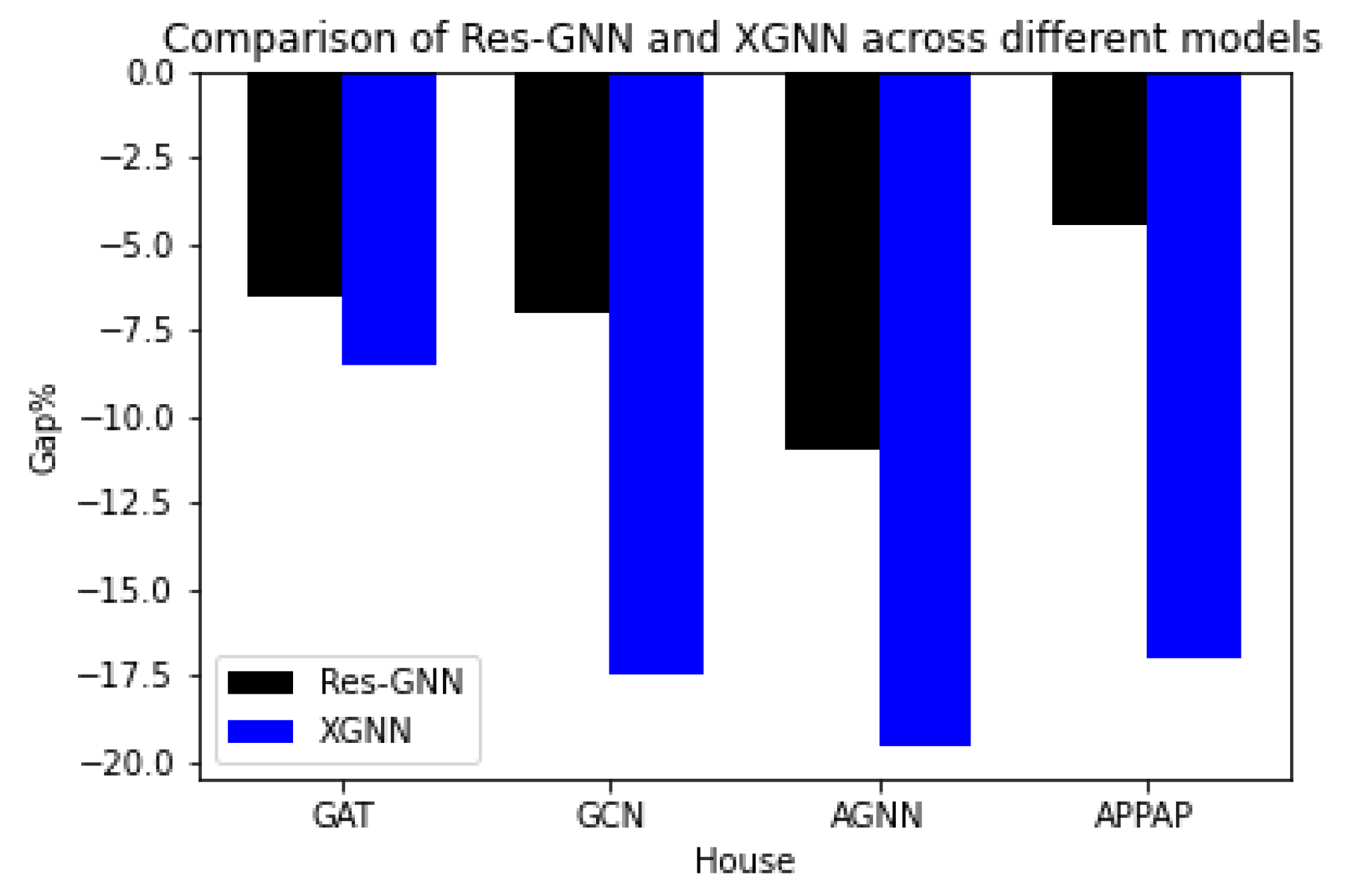

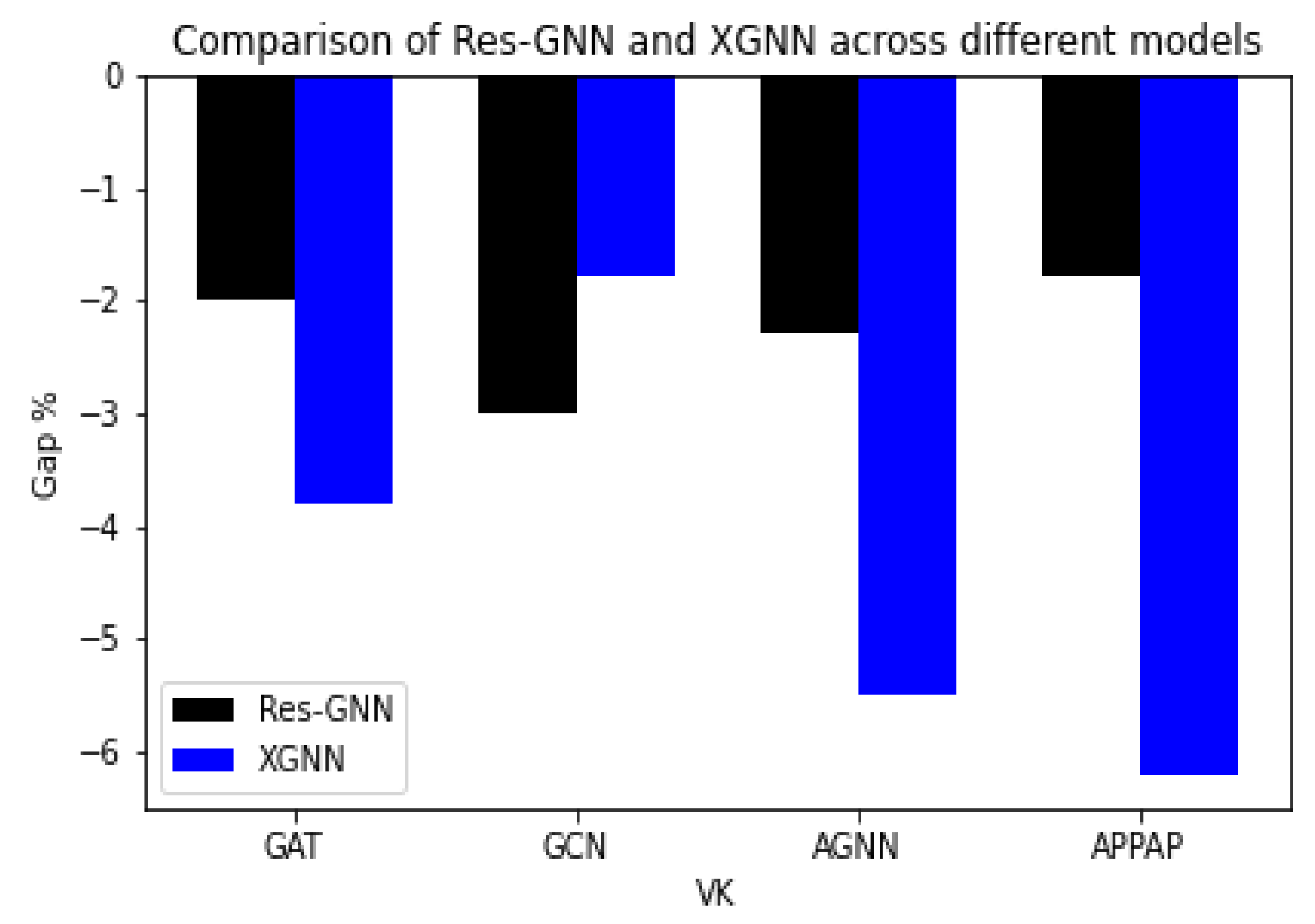

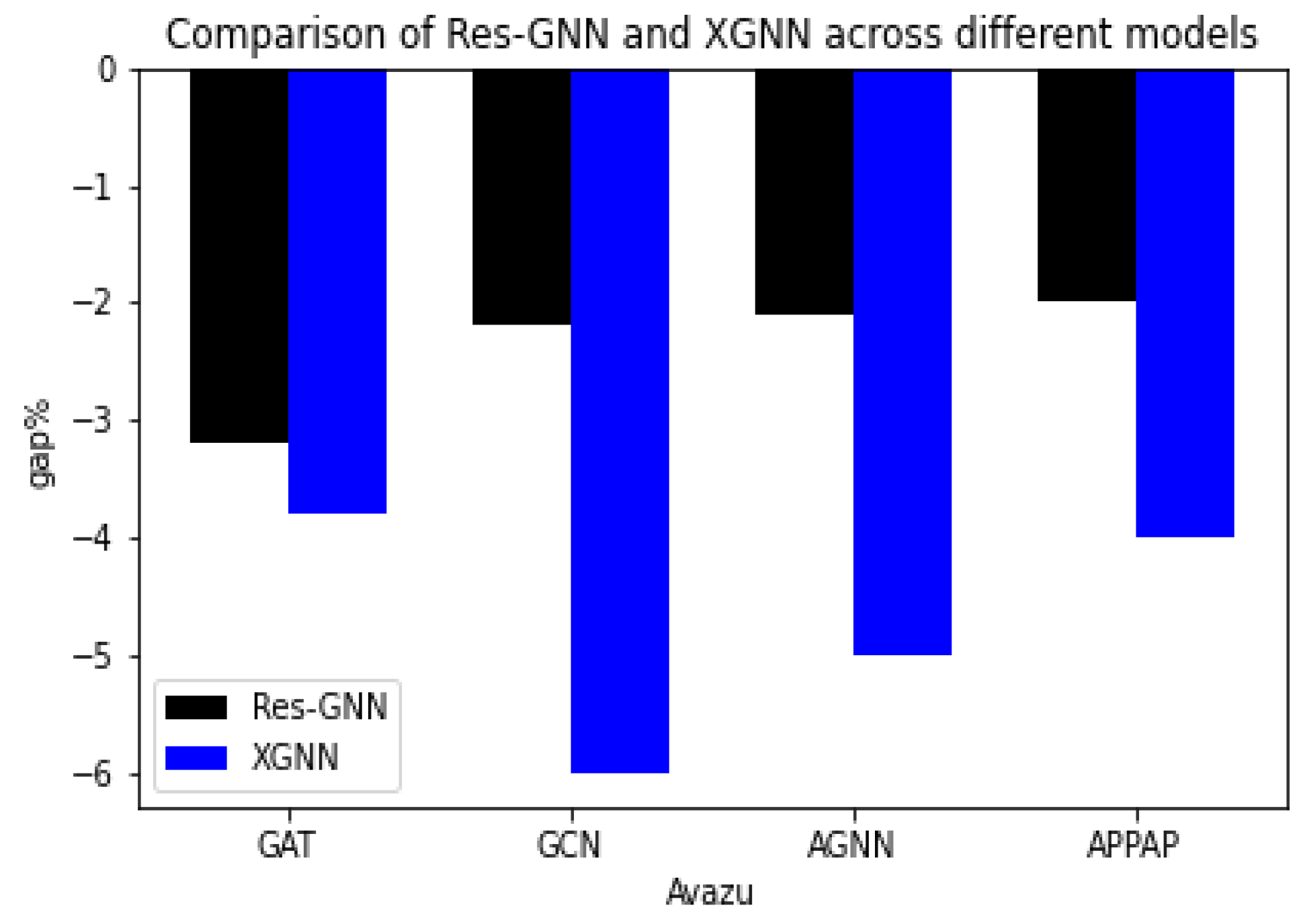

- We also investigated the use of four different types of graph neural networks co-trained with XGBoost, and experiments showed that using different types of graph neural networks, XGNN can still outperform other models.

2. Related Work

2.1. Tree-Based Table Model

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Table Models

2.3. Tabular Model Based on Graph Neural Network

3. Models and Methods

| Algorithm 1 Training of XGNN |

| 1. Input: Graph G, node features X, targets Y |

| 2. Initialize XGBoost targets y = Y |

| 3. for epoch i = 1 to N do |

| 4. # Train m trees of XGBoosts with Equations (2) and (3) |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. # Train l steps of GNN |

| 8. |

| 9. |

| 10. # Update targets for next iteration of XGBoosts |

| 11. |

| 12. end for |

| 13. Output: Models XGBoost f and GNN gθ |

3.1. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)

3.2. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

3.3. Why Use GNN for TDL?

- (1)

- Modelling instance correlation. When dealing with downstream tasks, it is necessary to consider not only the features of each instance itself but also the correlation between instances. The key idea is to learn high-quality feature representations of instances by modelling correlations between instances. If two instances have similar downstream labels, they may be closer in the feature space because they may share certain features or represent similar attributes. On the contrary, if two instances have different downstream labels, then they may be farther away from each other in the feature space because they may be significantly different from each other.

- (2)

- Feature interactions. In table prediction tasks, individual features may not be sufficient to adequately describe the data because there may be complex interactions between features. Traditional methods learn feature interactions by manually enumerating possible feature combinations, but this approach is time-consuming and requires domain knowledge. Deep learning methods can automatically learn feature interactions, but they usually simply connect the learned feature representations and cannot model structured correlations between features. However, GNNs can perform better in prediction tasks by learning how features interact in graph structures, naturally picking up on complex structured correlations between features, and making their own embeddings to show how features interact.

- (3)

- Higher-order connectivity. Higher-order connectivity refers to modelling complex relationships between data elements through the interaction of multiple hopping neighbors. To better learn the feature representation of data elements and improve prediction performance, higher-order connectivity between instances, between features, and between instances and features needs to be considered. In GNNs, through message passing and aggregation mechanisms, data elements can receive embed-dings from multi-hop neighbors in the graph to learn more complex relationships between data elements [22].

- (4)

- Monitoring signals. In some real-world applications, such as fraud detection, health prediction, and personalized marketing, it is challenging to collect a sufficient amount of tagged-form data. This is due to the fact that obtaining labelled data can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, often resulting in restricted access. However, graph neural networks are capable of learning without explicit instructions. This means that they can use the connections between the nodes in the graph to make better feature representations of unlabeled data, which helps with the supervised sparsity problem. We co-design the self-supervised task by combining the features and the graph structure, leveraging the semi-supervised learning property of graph neural networks. This further improves the model’s performance on the supervised sparsity problem and brings new breakthroughs in tabular data learning.

- (5)

- Generalization ability. GNNs can learn to generalize what they have learned from training data. This means that even if they see nodes or graph structures, they have not seen before, they can still figure out what the results should be based on the patterns they have learned from the training data. During the testing phase, they can incorporate additional features and perform feature extrapolation to learn how to represent tabular data. The ability to generalize to unseen tasks, i.e., tasks not learned during the training phase, is another crucial aspect. This implies that GNNs, when learning representations of tabular data, can apply to new, unknown tasks without requiring retraining or parameter tuning [23].

4. Experiment

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Compared Algorithms

- (1)

- CatBoost: A decision tree algorithm based on gradient boosting, especially suitable for dealing with category-based features.

- (2)

- LightGBM: An efficient gradient-boosting framework optimized for large-scale data training speed and memory usage.

- (3)

- GAT: Graph Attention Network, which improves the representation of graph data by dynamically distributing the weights of node neighbors through an attention mechanism.

- (4)

- GCN: Graph Convolutional Networks, which efficiently capture information about nodes and their neighbors through local graph convolution operations.

- (5)

- AGNN: Attention Graph Neural Network, which utilizes the attention mechanism to weight the information in the graph for summarization.

- (6)

- APPNP: Predictive Personalization Propagation-Based Graph Neural Network, combining neural networks with PageRank propagation.

- (7)

- FCNN: The Fully Connected Neural Network, which consists of multiple layers of fully connected neurons, is suitable for feature learning for multiple tasks.

- (8)

- FCNN-GNN (F-GNN): combines fully connected neural networks with graph neural networks to utilize graph structure information for more complex feature learning.

- (9)

- BestowGNN + C&S [32]: A robust stacking framework that integrates and stacks IID data in multiple layers, fusing graph-aware propagation and arbitrary models.

- (10)

- Res-GNN: First, train a GBDT model on the training set of nodes, append or replace the original node features with their predictions for all nodes, and then train a GNN on the updated features.

- (11)

- XGNN: Simultaneous training of XGBoost and GNN in an end-to-end manner.

4.3. Settings

4.4. Results

4.5. Training Time

4.6. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ulmer, D.; Meijerink, L.; Cinà, G. Trust issues: Uncertainty estimation does not enable reliable ood detection on medical tabular data. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Health, Durham, NC, USA, 7–8 August 2020; pp. 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, J.M.; Xu, D.; Yousefi, N.; Efimov, D. Sequential deep learning for credit risk monitoring with tabular financial data. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.15330. [Google Scholar]

- McElfresh, D.; Khandagale, S.; Valverde, J.; Prasad, C.V.; Ramakrishnan, G.; Goldblum, M.; White, C. When do neural nets outperform boosted trees on tabular data? In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’23), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; pp. 76336–76369. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Ding, B.; Gürel, N.M.; Zhang, C.; Huang, M.; Lin, W.; Zhou, J. Fives: Feature interaction via edge search for large-scale tabular data. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 3795–3805. [Google Scholar]

- Bentéjac, C.; Csörgő, A.; Martínez-Muñoz, G. A comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 1937–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagi, O.; Rokach, L. Approximating XGBoost with an interpretable decision tree. Inf. Sci. 2021, 572, 522–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’18), Montreal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; pp. 6639–6649. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Meng, Q.; Finley, T.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Ma, W.; Ye, Q.; Liu, T.-Y. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS’17), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 3149–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Grinsztajn, L.; Oyallon, E.; Varoquaux, G. Why do tree-based models still outperform deep learning on typical tabular data? Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 507–520. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, S.; Morozov, S.; Babenko, A. Neural oblivious decision ensembles for deep learning on tabular data. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.06312. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, G.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Bian, J.; Liu, T.-Y. TabNN: A universal neural network solution for tabular data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2019), New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal, S.S.; Vishwanath, D.; Rahul, R.; Sharma, M.; Vig, L. Tablenet: Deep learning model for end-to-end table detection and tabular data extraction from scanned document images. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), Sydney, Australia, 20–25 September 2019; pp. 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, D.; Gadpal, A.; Kapadni, K.; Visave, M.; Sultanpure, K. CascadeTabNet: An approach for end to end table detection and structure recognition from image-based documents. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 572–573. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Quan, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yao, Q.; Li, Y.; Tu, W. Tabgnn: Multiplex graph neural network for tabular data prediction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2108.09127. [Google Scholar]

- Telyatnikov, L.; Scardapane, S. EGG-GAE: Scalable graph neural networks for tabular data imputation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Valencia, Spain, 25–27 April 2023; pp. 2661–2676. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.; Gao, F.; Chen, X.; Jia, R.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Han, S.; Zhang, D. TabularNet: A neural network architecture for understanding semantic structures of tabular data. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 322–331. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.C.; Li, C.-T. TabGSL: Graph Structure Learning for Tabular Data Prediction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.15843. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Choi, H.-S.; Kim, J. Explicit Feature Interaction-aware Graph Neural Network. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 15438–15446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodge, A.; Hooi, B.; Ng, S.-K.; Ng, W.S. Lunar: Unifying local outlier detection methods via graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 22 February–1 March 2022; pp. 6737–6745. [Google Scholar]

- Hettige, B.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.-F.; Le, S.; Buntine, W. MedGraph: Structural and temporal representation learning of electronic medical records. In ECAI Digital 2020—24th European Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 29 August–8 September 2020; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1810–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J.; Sun, D.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Feng, S.; Wang, Z. Heterogeneous Graph-Convolution-Network-Based Short-Text Classification. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Tao, W.; Cui, X. Affective-knowledge-enhanced graph convolutional networks for aspect-based sentiment analysis with multi-head attention. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Ma, X.; Ding, Y.; Kochenderfer, M.J.; Leskovec, J. Handling missing data with graph representation learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 19075–19087. [Google Scholar]

- Seyedrezaei, M.; Tak, A.N.; Becerik-Gerber, B. Consumption and conservation behaviors among affordable housing residents in Southern California. Energy Build. 2024, 304, 113840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Benson, A.R. Residual correlation in graph neural network regression. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual Event, 23–27 August 2020; pp. 588–598. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsulin, A.; Mottin, D.; Karras, P.; Müller, E. Verse: Versatile graph embeddings from similarity measures. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; pp. 539–548. [Google Scholar]

- Rozemberczki, B.; Allen, C.; Sarkar, R. Multi-scale attributed node embedding. J. Complex Netw. 2021, 9, cnab014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Shi, C.; Xiao, Z.; Duan, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tang, J. Autoint: Automatic feature interaction learning via self-attentive neural networks. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Beijing, China, 3–7 November 2019; pp. 1161–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Zhai, C. Non-local attention learning on large heterogeneous information networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 December 2019; pp. 978–987. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Liu, B.; Huang, C.; Dai, P.; Bo, L.; Zhang, J. Heterogeneous deep graph infomax. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.08538. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Fey, M.; Zitnik, M.; Dong, Y.; Ren, H.; Liu, B.; Catasta, M.; Leskovec, J. Open graph benchmark: Datasets for machine learning on graphs. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 22118–22133. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Mueller, J.; Ioannidis, V.N.; Goldstein, T.; Wipf, D. A Robust Stacking Framework for Training Deep Graph Models with Multifaceted Node Features. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.08473. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | House | County | VK | Avazu | Wiki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #Nodes | 20,640 | 3217 | 54,028 | 1297 | 5201 |

| #Edges | 182,146 | 12,684 | 213,644 | 54,364 | 198,493 |

| #Features/Node | 6 | 7 | 14 | 9 | 3148 |

| Mean Target | 2.06 | 5.44 | 35.47 | 0.08 | 27,923.76 |

| Min Target | 0.14 | 1.7 | 13.48 | 0 | 16 |

| Max Target | 5.00 | 24.1 | 118.39 | 1 | 849,131 |

| Median Target | 1.79 | 5 | 33.83 | 0 | 9225 |

| Dataset | SLAP | DBLP | OGB-ArXiv |

|---|---|---|---|

| #Nodes | 20,419 | 14,475 | 169,343 |

| #Edges | 172,248 | 40,269 | 1,166,243 |

| #Features/Node | 2701 | 5002 | 128 |

| Classes | 15 | 4 | 40 |

| Min Class | 103 | 745 | 29 |

| Max Class | 534 | 1197 | 27,321 |

| Dataset | House | County | VK | Avazu | Wiki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.07 | 7.16 ± 0.20 | 0.1172 ± 0.02 | 46,359 ± 4508 |

| LightGBM | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | 7.16 ± 0.20 | 0.1171 ± 0.02 | 49,915 ± 3643 |

| GCN | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 1.48 ± 0.08 | 7.25 ± 0.19 | 0.1141 ± 0.02 | 44,936 ± 4083 |

| GAT | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 1.45 ± 0.06 | 7.22 ± 0.19 | 0.1134 ± 0.01 | 45,916 ± 4527 |

| APPNP | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.11 | 13.23 ± 0.12 | 0.1127 ± 0.01 | 53,426 ± 4159 |

| AGNN | 0.59 ± 0.01 | 1.45 ± 0.08 | 7.26 ± 0.20 | 0.1134 ± 0.02 | 45,982 ± 3058 |

| FCNN | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 1.48 ± 0.07 | 7.29 ± 0.21 | 0.118 ± 0.02 | 51,662 ± 2983 |

| F-GNN | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.06 | 7.22 ± 0.20 | 0.1114 ± 0.02 | 48,491 ± 7889 |

| BestowGNN + C&S | 0.467 ± 0.01 | 1.145 ± 0.08 | 6.918 ± 0.22 | 0.105 ± 0.01 | - |

| RES-GNN | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 1.33 ± 0.08 | 7.07 ± 0.20 | 0.1095 ± 0.01 | 46,747 ± 4639 |

| XGNN | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | 6.847 ± 0.20 | 0.097 ± 0.01 | 49,222 ± 3743 |

| Dataset | House | County | VK | Avazu | Wiki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.07 | 7.16 ± 0.20 | 0.1172 ± 0.02 | 46,359 ± 4508 |

| LightGBM | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 1.4 ± 0.07 | 7.16 ± 0.20 | 0.1171 ± 0.02 | 49,915 ± 3643 |

| GCN | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 1.48 ± 0.08 | 7.25 ± 0.19 | 0.1141 ± 0.02 | 44,936 ± 4083 |

| GAT | 0.54 ± 0.01 | 1.45 ± 0.06 | 7.22 ± 0.19 | 0.1134 ± 0.01 | 45,916 ± 4527 |

| APPNP | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.11 | 13.23 ± 0.12 | 0.1127 ± 0.01 | 53,426 ± 4159 |

| AGNN | 0.59 ± 0.01 | 1.45 ± 0.08 | 7.26 ± 0.20 | 0.1134 ± 0.02 | 45,982 ± 3058 |

| FCNN | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 1.48 ± 0.07 | 7.29 ± 0.21 | 0.118 ± 0.02 | 51,662 ± 2983 |

| F-GNN | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 1.39 ± 0.06 | 7.22 ± 0.20 | 0.1114 ± 0.02 | 48,491 ± 7889 |

| BestowGNN + C&S | 0.467 ± 0.01 | 1.145 ± 0.08 | 6.918 ± 0.22 | 0.105 ± 0.01 | - |

| RES-GNN | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 1.33 ± 0.08 | 7.07 ± 0.20 | 0.1095 ± 0.01 | 46,747 ± 4639 |

| XGNN | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 1.09 ± 0.08 | 6.847 ± 0.20 | 0.097 ± 0.01 | 49,222 ± 3743 |

| Dataset | House | County | VK | Avazu | Wiki |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 4 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 24 ± 4 | 10 ± 1 | 2 ± 2 |

| LightGBM | 3 ± 0 | 1 ± 0 | 5 ± 3 | 3 ± 2 | 0 ± 0 |

| GCN | 28 ± 0 | 18 ± 7 | 38 ± 0 | 13 ± 3 | 12 ± 6 |

| GAT | 35 ± 2 | 19 ± 6 | 42 ± 4 | 15 ± 1 | 9 ± 2 |

| APPNP | 68 ± 1 | 34 ± 10 | 81 ± 3 | 81 ± 3 | 24 ± 15 |

| AGNN | 38 ± 5 | 28 ± 3 | 48 ± 3 | 19 ± 5 | 14 ± 8 |

| FCNN | 68 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 109 ± 35 | 12 ± 2 | 2 ± 0 |

| F-GNN | 39 ± 1 | 21 ± 6 | 48 ± 2 | 16 ± 1 | 14 ± 3 |

| BestowGNN + C&S | 52 ± 1 | 18 ± 0 | 119 ± 0 | 15 ± 1 | - |

| RES-GNN | 36 ± 7 | 7 ± 3 | 41 ± 1 | 31 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 |

| XGNN | 19 ± 4 | 2 ± 0 | 15 ± 0 | 20 ± 3 | 4 ± 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, L.; Xu, Y. XGBoost-Enhanced Graph Neural Networks: A New Architecture for Heterogeneous Tabular Data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5826. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135826

Yan L, Xu Y. XGBoost-Enhanced Graph Neural Networks: A New Architecture for Heterogeneous Tabular Data. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(13):5826. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135826

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Liuxi, and Yaoqun Xu. 2024. "XGBoost-Enhanced Graph Neural Networks: A New Architecture for Heterogeneous Tabular Data" Applied Sciences 14, no. 13: 5826. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135826

APA StyleYan, L., & Xu, Y. (2024). XGBoost-Enhanced Graph Neural Networks: A New Architecture for Heterogeneous Tabular Data. Applied Sciences, 14(13), 5826. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135826