RockDNet: Deep Learning Approach for Lithology Classification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

3.1. Image Augmentation

3.2. Transfer Learning

3.3. Proposed CNN Model

3.4. Batch Size

4. Experimental Results

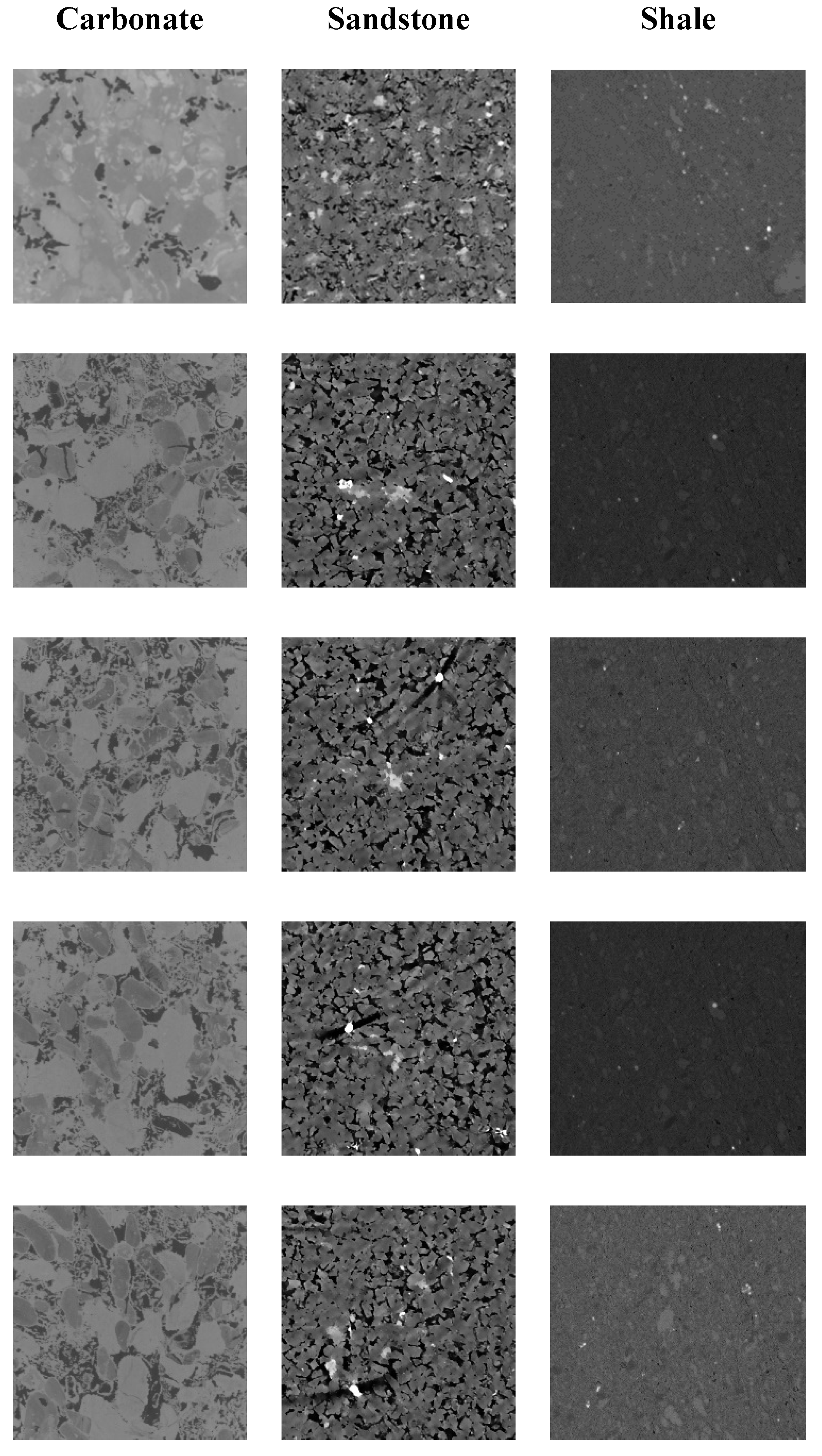

4.1. Dataset

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

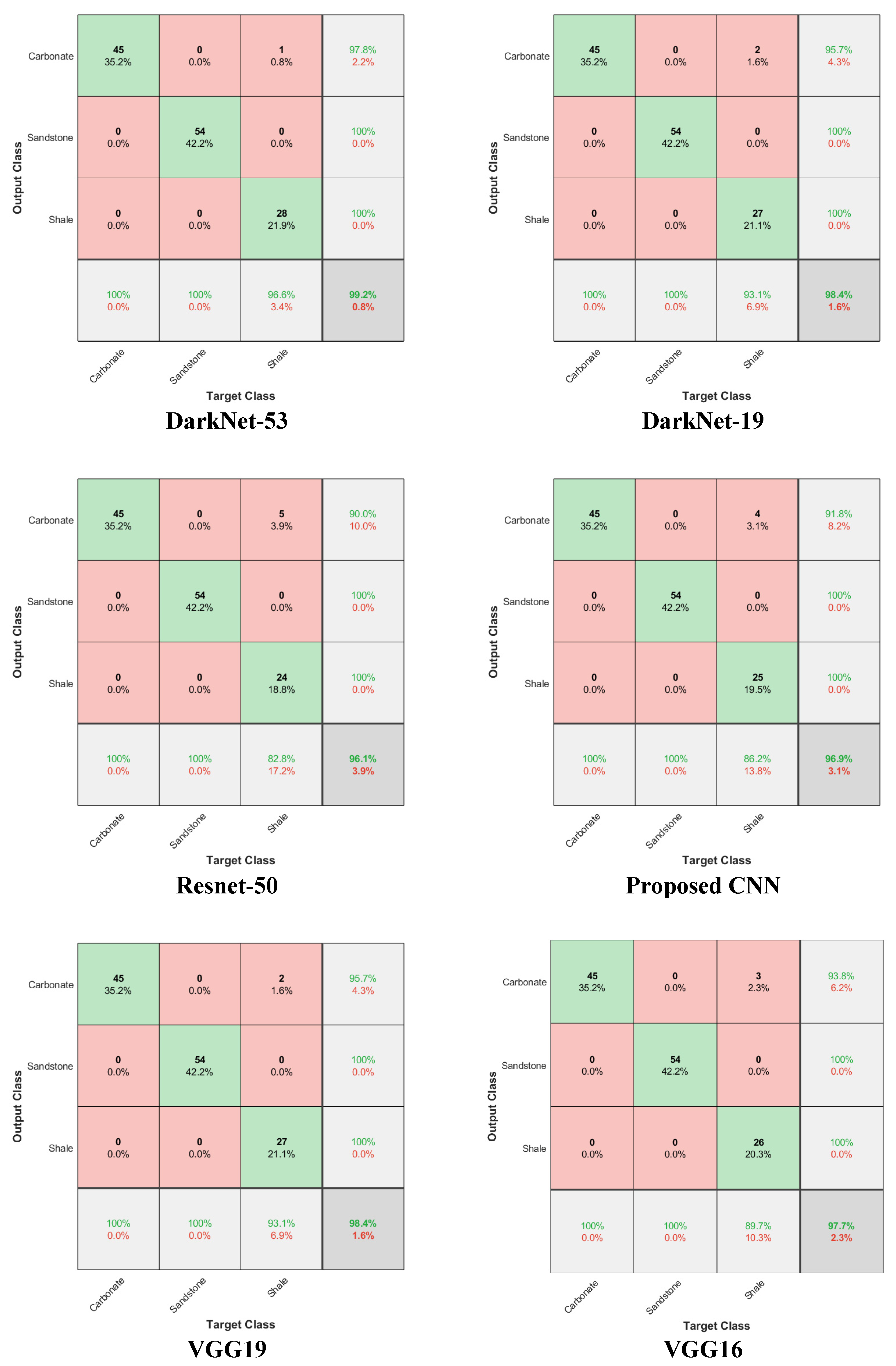

4.3. CNN Models Training and Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, D.; Su, C.; Wang, W.; Yuan, R. Deep learning based lithology classification of drill core images. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, F.; Mostaghimi, P.; Swietojanski, P.; Clark, S.R.; Armstrong, R.T. Automated lithology classification from drill core images using convolutional neural networks. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 197, 107933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawshin, K.; Berg, C.F.; Varagnolo, D.; Lopez, O. A deep-learning approach for lithological classification using 3D whole core CT-scan images. In Proceedings of the SPWLA Annual Logging Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 17 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A.; Rider, M.; Curtis, A.; MacArthur, A. Automated lithology extraction from core photographs. First Break 2011, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caja, M.Á.; Peña, A.C.; Campos, J.R.; García, D.L.; Tritlla, J.; Bover-Arnal, T.; Martín-Martín, J.D. Image processing and machine learning applied to lithology identification, classification and quantification of thin section cutting samples. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; He, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, G. Classification of rock fragments produced by tunnel boring machine using convolutional neural networks. Autom. Constr. 2021, 125, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mudhafar, W.J. Integrating well log interpretations for lithofacies classification and permeability modeling through advanced machine learning algorithms. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2017, 7, 1023–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Pan, H.; Fang, S.; Konaté, A.A.; Qin, R. Support vector machine as an alternative method for lithology classification of crystalline rocks. J. Geophy. Eng. 2017, 14, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebtosheikh, M.A.; Salehi, A. Lithology prediction by support vector classifiers using inverted seismic attributes data and petrophysical logs as a new approach and investigation of training data set size effect on its performance in a heterogeneous carbonate reservoir. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2015, 134, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawshin, K.; Gonzalez, A.; Berg, C.F.; Varagnolo, D.; Heidari, Z.; Lopez, O. Classifying lithofacies from textural features in whole core CT-scan images. SPE Res. Eval. Eng. 2021, 24, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires de Lima, R.; Suriamin, F.; Marfurt, K.J.; Pranter, M.J. Convolutional neural networks as aid in core lithofacies classification. Interpretation 2019, 7, SF27–SF40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, R.P.; Bonar, A.; Coronado, D.D.; Marfurt, K.; Nicholson, C. Deep convolutional neural networks as a geological image classification tool. Sediment. Rec. 2019, 17, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, R.P.; Duarte, D.; Nicholson, C.; Slatt, R.; Marfurt, K.J. Petrographic microfacies classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Comput. Geosci. 2020, 142, 104481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Kanyan, L.; Heidari, Z.; Lopez, O. Integrated multi-physics workflow for automatic rock classification and formation evaluation using multi-scale image analysis and conventional well logs. In Proceedings of the SPWLA Annual Logging Symposium, The Woodlands, TX, USA, 15 June 2019; p. D033S001R001. [Google Scholar]

- Antariksa, G.; Muammar, R.; Lee, J. Performance evaluation of machine learning-based classification with rock-physics analysis of geological lithofacies in Tarakan Basin, Indonesia. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babović, Z.; Bajat, B.; Đokić, V.; Đorđević, F.; Drašković, D.; Filipović, N.; Furht, B.; Gačić, N.; Ikodinović, I.; Ilić, M.; et al. Research in computing-intensive simulations for nature-oriented civil-engineering and related scientific fields, using machine learning and big data: An overview of open problems. J. Big Data 2023, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:14091556. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA,, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Shi, G.; Tao, J.; Yu, H.; Jin, Y.; Lei, J.; Liu, C. Precise cutterhead torque prediction for shield tunneling machines using a novel hybrid deep neural network. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 151, 107386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, N.; Alzubaidi, F.; Armstrong, R.T.; Swietojanski, P.; Mostaghimi, P. Machine learning for predicting properties of porous media from 2d X-ray images. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 184, 106514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpouli, S.; Tahmasebi, P. Segmentation of digital rock images using deep convolutional autoencoder networks. Comput. Geosci. 2019, 126, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Wang, Y.; Armstrong, R.; Mostaghimi, P. Super resolution convolutional neural network models for enhancing resolution of rock micro-ct images. arXiv 2019, arXiv:190407470. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, X.; Xue, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sang, X.; He, J. Rock classification from field image patches analyzed using a deep convolutional neural network. Mathematics 2019, 7, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraboshkin, E.E.; Ismailova, L.S.; Orlov, D.M.; Zhukovskaya, E.A.; Kalmykov, G.A.; Khotylev, O.V. Deep convolutions for in-depth automated rock typing. Comput. Geosci. 2020, 135, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Girshick, R.; Dollár, P.; Tu, Z.; He, K. Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Anjos, C.E.; Avila, M.R.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; Pereira Neta, A.M.; Medeiros, L.C.; Evsukoff, A.G. Deep learning for lithological classification of carbonate rock micro-CT images. Comput. Geosci. 2021, 25, 971–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Gao, J. Deep learning method for lithology identification from borehole images. In Proceedings of the 79th EAGE Conference and Exhibition, Paris, France, 12–15 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Well-Logging-Based Lithology Classification Using Machine Learning Methods for High-Quality Reservoir Identification: A Case Study of Baikouquan Formation in Mahu Area of Junggar Basin, NW China. Energies 2022, 15, 3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Fu, J.; Jiang, R.; Li, G.; Yang, Q. Lithological Classification by Hyperspectral Images Based on a Two-Layer XGBoost Model, Combined with a Greedy Algorithm. Remote Sen. 2023, 15, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, Ö.; Polat, A.; Ekici, T. Classification of plutonic rock types using thin section images with deep transfer learning. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2021, 30, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, Ö.; Polat, A.; Ekici, T. Automatic classification of volcanic rocks from thin section images using transfer learning networks. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 11531–11540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodanovic, M.; Esteva, M.; Hanlon, M.; Nanda, G.; Agarwal, P. Digital Rocks Portal: A Repository for Porous Media Images; US National Science Foundation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jasim, A.M.; Awad, S.R.; Malallah, F.L.; Abdul-Jabbar, J.M. Efficient Gender Classifier for Arabic Speech Using CNN with Dimensional Reshaping. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Information Engineering (ICEEIE), Malang, Indonesia, 2 October 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, S.R.; Sharef, B.T.; Salih, A.M.; Malallah, F.L. Deep learning-based Iraqi banknotes classification system for blind people. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2022, 1, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zuo, R.; Liu, H. Lithological mapping based on fully convolutional network and multi-source geological data. Remote Sen. 2021, 13, 4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Gu, B. A Lithology Recognition Network Based on Attention and Feature Brownian Distance Covariance. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Training Options | |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | SGDM |

| Initial learn rate | 0.0001 |

| Learn rate drop factor | 0.01 |

| Max epochs | 40 |

| Activation function | ReLU |

| Shuffle | Every epoch |

| Validation frequency | 60 |

| Execution environment | Single GPU |

| Mini batch size | 64 |

| Computer specifications used in training and classification: CPU CORE I7-12700H/RAM 16GB/GPU RTX3060-6GB | |

| Model Name | Number of Layers | Number of Connections | Depth | Size on Disk (MB) | Parameters | Classification Time (Second) | Input Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed CNN | 15 | 18 | 5 | 0.204 | 69,602 | 1.8 | 128 × 128 × 3 |

| No. | Layer Name | Output Shape |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Input Image | 128 × 128 × 3 |

| 2 | 2-D Convolution | 128 × 128 × 10 |

| 3 | Batch Normalization | 128 × 128 × 10 |

| 4 | 2-D Max Pooling | 64 × 64 × 10 |

| 5 | 2-D Convolution | 64 × 64 × 20 |

| 6 | Batch Normalization | 64 × 64 × 20 |

| 7 | 2-D Max Pooling | 32 × 32× 20 |

| 8 | 2-D Convolution | 32 × 32 × 64 |

| 9 | Batch Normalization | 32 × 32 × 64 |

| 10 | 2-D Max Pooling | 16 × 16 × 64 |

| 11 | 2-D Convolution | 16 × 16 × 30 |

| 12 | Batch Normalization | 16 × 16 × 30 |

| 13 | Fully Connected | 1 × 1 × 3 |

| 14 | SoftMax | 1 × 1 × 3 |

| 15 | Classification Output | 1 × 1 × 3 |

| Maximum number of learnable parameters | 69,602 | |

| Class\Precious Stones Type | Number of Samples | Training (80%) | Testing (20%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonate | 239 | 191 | 48 |

| Sandstone | 196 | 156 | 40 |

| Shale | 211 | 169 | 42 |

| Total | 646 | 516 | 130 |

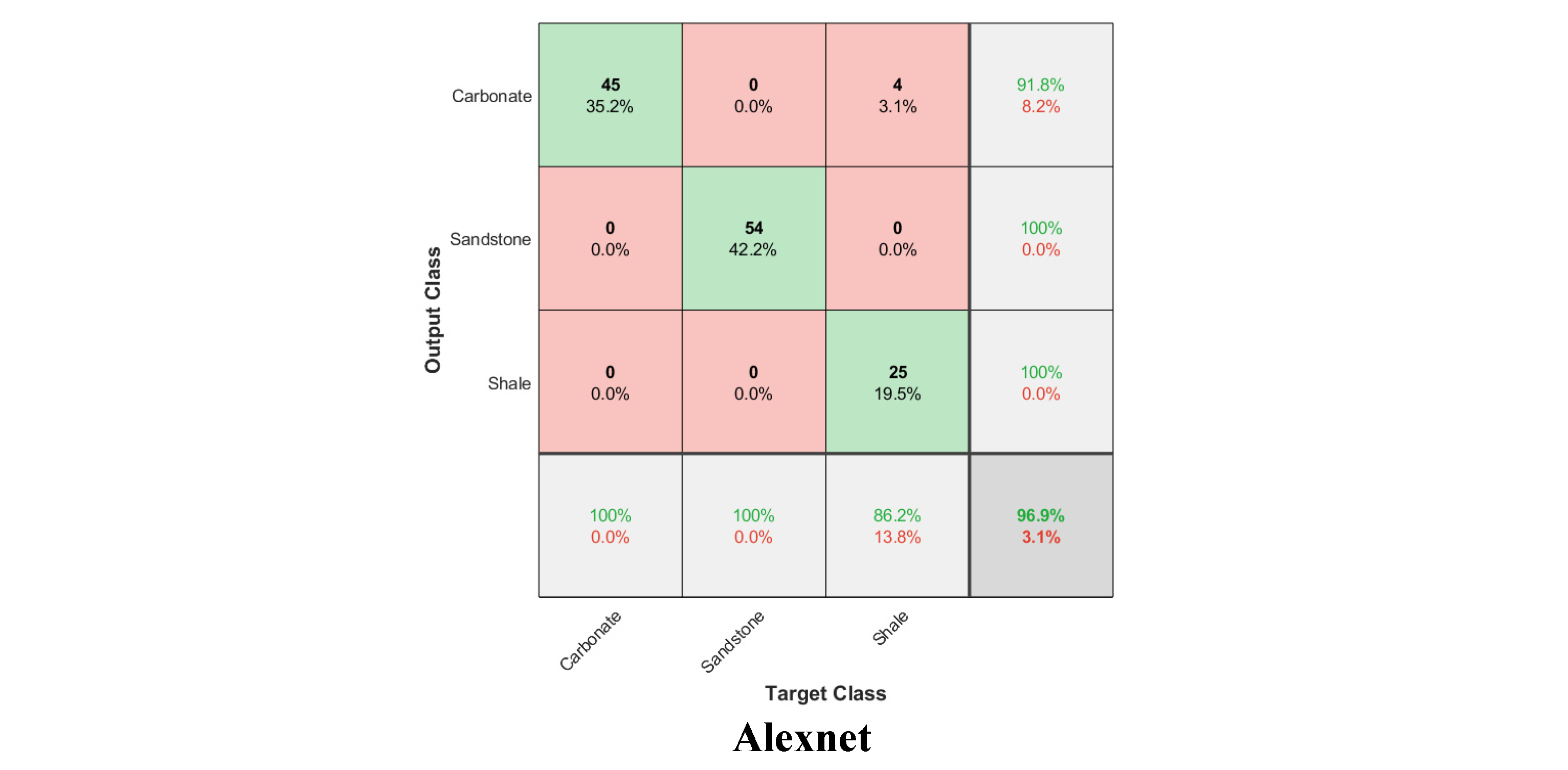

| Classification Model Name | Class | Precision % for Testing Data | Recall % for Testing Data | F1-Score % for Testing Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darknet-53 | Carbonate | 97.8 | 100 | 98.9 |

| Sandstone | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Shale | 100 | 96.6 | 98.2 | |

| Darknet-19 | Carbonate | 95.7 | 100 | 97.8 |

| Sandstone | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Shale | 100 | 93.1 | 96.4 | |

| Resnet-50 | Carbonate | 90 | 100 | 94.7 |

| Sandstone | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Shale | 100 | 82.8 | 90.6 | |

| Proposed 15 layers CNN | Carbonate | 91.8 | 100 | 95.7 |

| Sandstone | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Shale | 100 | 86.2 | 92.6 | |

| VGG 19 | Carbonate | 95.7 | 100 | 97.8 |

| Sandstone | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Shale | 100 | 93.1 | 96.4 | |

| VGG 16 | Carbonate | 93.8 | 100 | 96.8 |

| Sandstone | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Shale | 100 | 89.7 | 94.5 | |

| Alex-Net | Carbonate | 91.8 | 100 | 95.7 |

| Sandstone | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Shale | 100 | 86.2 | 92.6 |

| Employed Model | Average Precision % | Average Recall % | Average F1-Score % | Average Accuracy % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darknet-53 | 99.3 | 98.9 | 99.1 | 99.22 |

| Darknet-19 | 98.6 | 97.7 | 98.1 | 98.4 |

| Resnet-50 | 96.7 | 94.3 | 95.5 | 96.1 |

| Proposed CNN | 97.3 | 95.4 | 96.3 | 96.9 |

| VGG 19 | 98.6 | 97.7 | 98.1 | 98.4 |

| VGG 16 | 97.9 | 96.6 | 97.2 | 97.7 |

| Alex-Net | 97.3 | 95.4 | 96.3 | 96.9 |

| Classification Model Name | Number of Layers | Depth | Number of Learnable Parameters | Number of Connections | Size on Disk | Classification Time (Second) for Testing Set | Accuracy % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darknet-53 | 185 | 53 | 41 M | 207 | 148 MB | 4.66 | 99.22 |

| Darknet-19 | 65 | 19 | 19.5 M | 64 | 74.1 MB | 2.94 | 98.4 |

| Resnet-50 | 177 | 50 | 23.6 M | 192 | 83.7 MB | 3.68 | 96.1 |

| Vgg19 | 47 | 19 | 143 M | 46 | 495 MB | 6.35 | 98.4 |

| Vgg16 | 41 | 16 | 138 M | 40 | 476 MB | 5.8 | 97.7 |

| AlexNet | 25 | 8 | 60.02 M | 24 | 201 MB | 3.78 | 96.9 |

| Proposed CNN | 15 | 5 | 69.6 K | 18 | 204 KB | 1.8 | 96.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdullah, M.A.M.; Mohammed, A.A.; Awad, S.R. RockDNet: Deep Learning Approach for Lithology Classification. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5511. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135511

Abdullah MAM, Mohammed AA, Awad SR. RockDNet: Deep Learning Approach for Lithology Classification. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(13):5511. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135511

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Mohammed A. M., Ahmed A. Mohammed, and Sohaib R. Awad. 2024. "RockDNet: Deep Learning Approach for Lithology Classification" Applied Sciences 14, no. 13: 5511. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135511

APA StyleAbdullah, M. A. M., Mohammed, A. A., & Awad, S. R. (2024). RockDNet: Deep Learning Approach for Lithology Classification. Applied Sciences, 14(13), 5511. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14135511