Prevalence and Clinical Consideration of Anatomical Variants of the Splenic Artery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

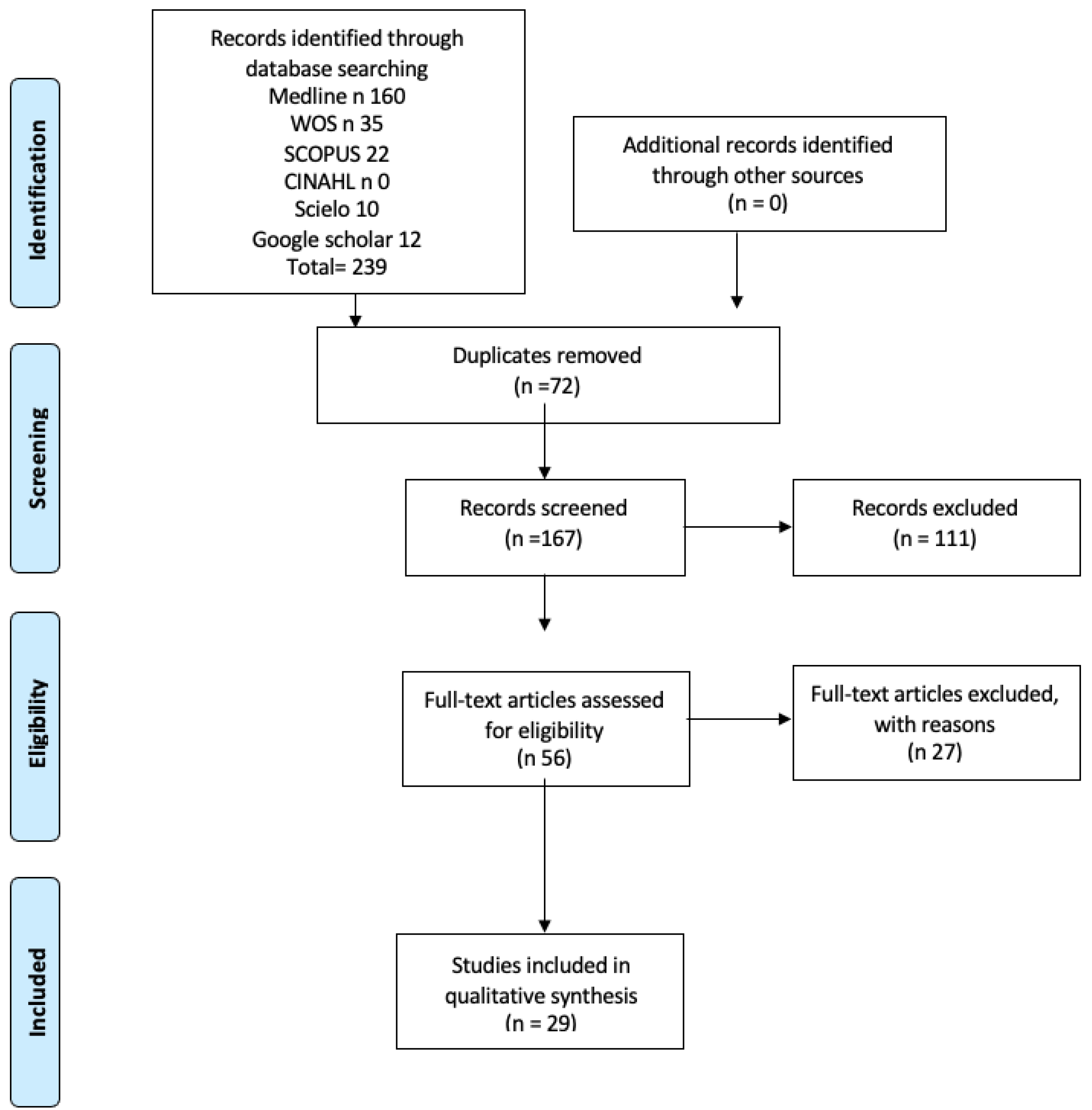

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

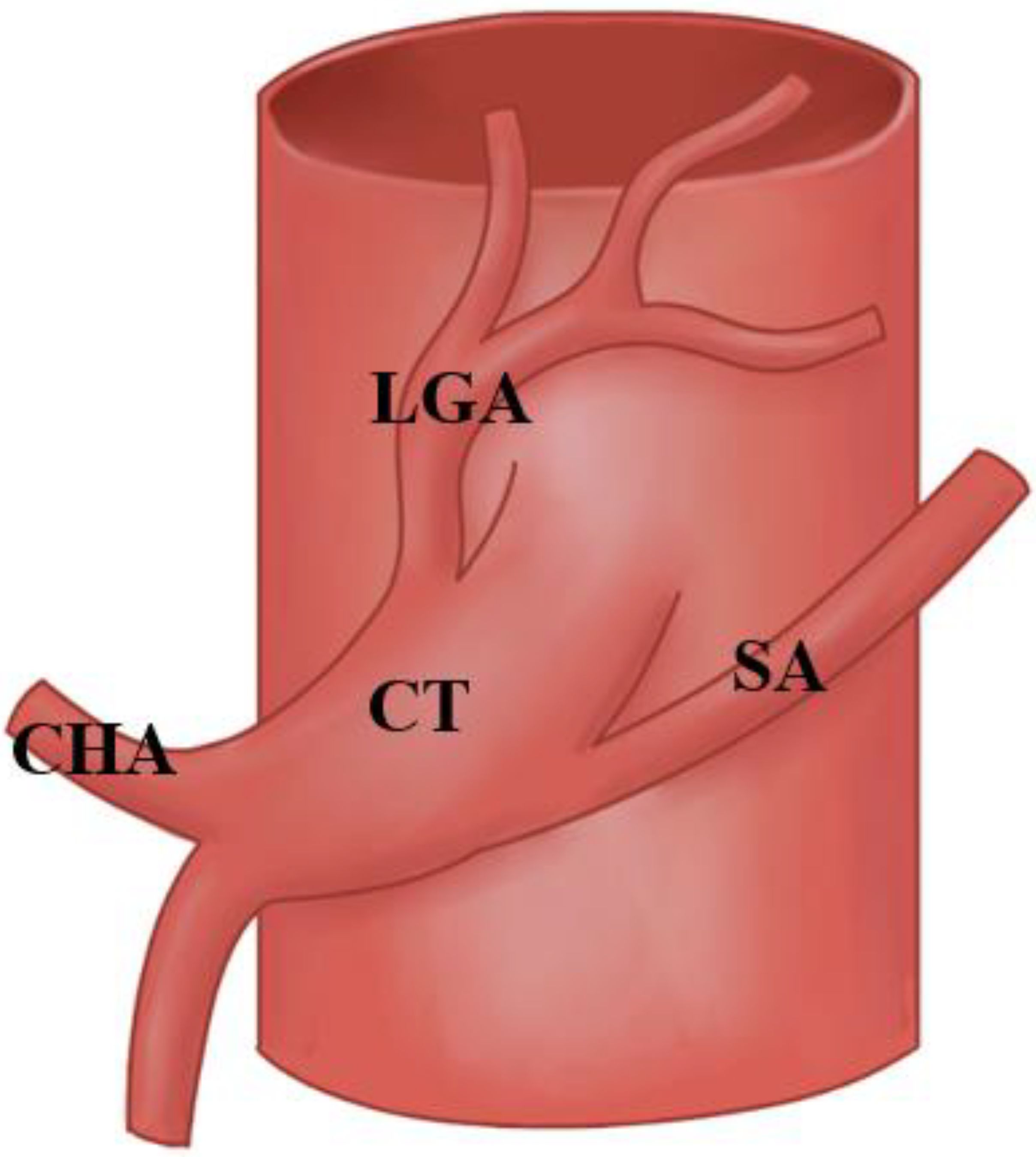

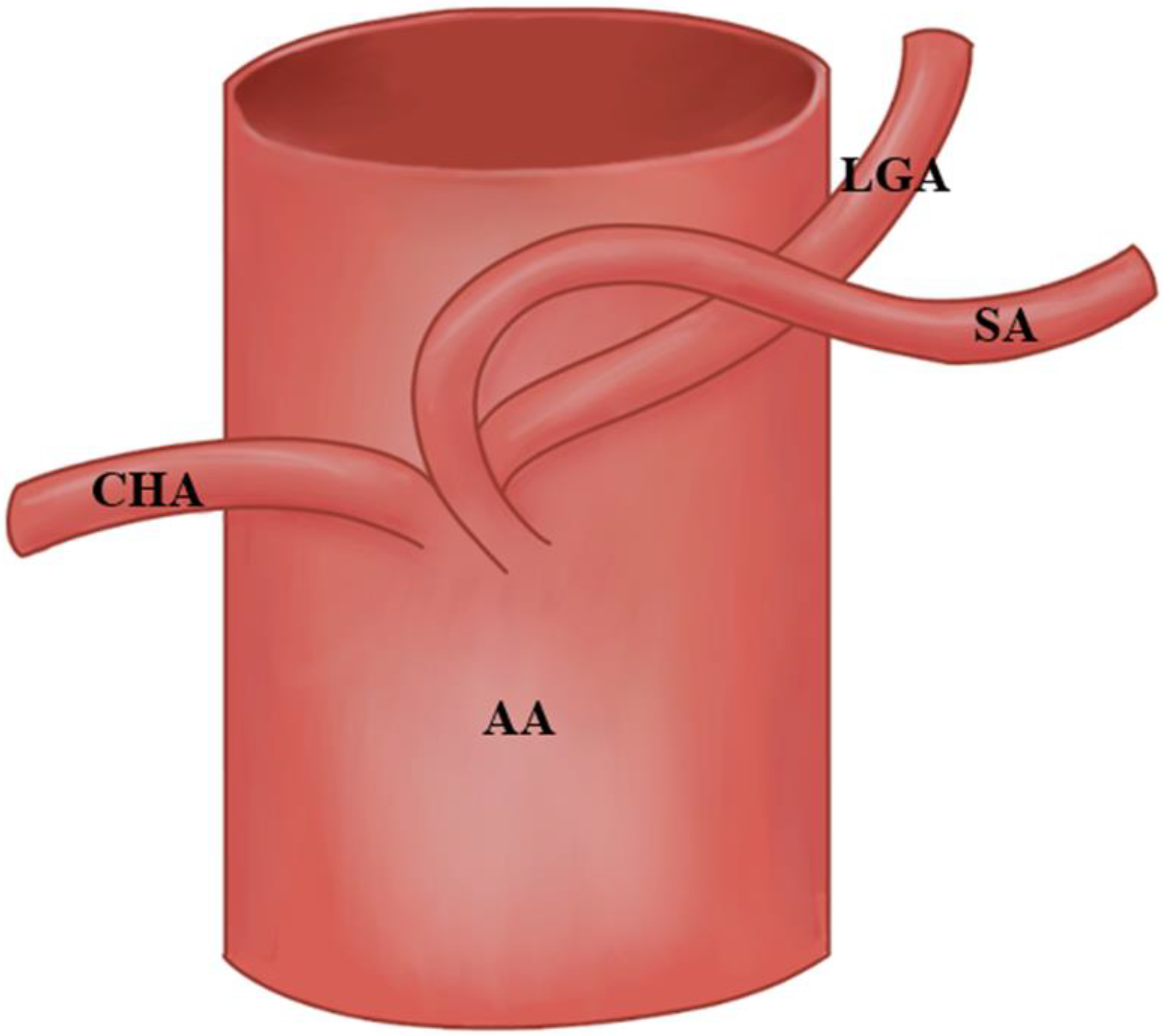

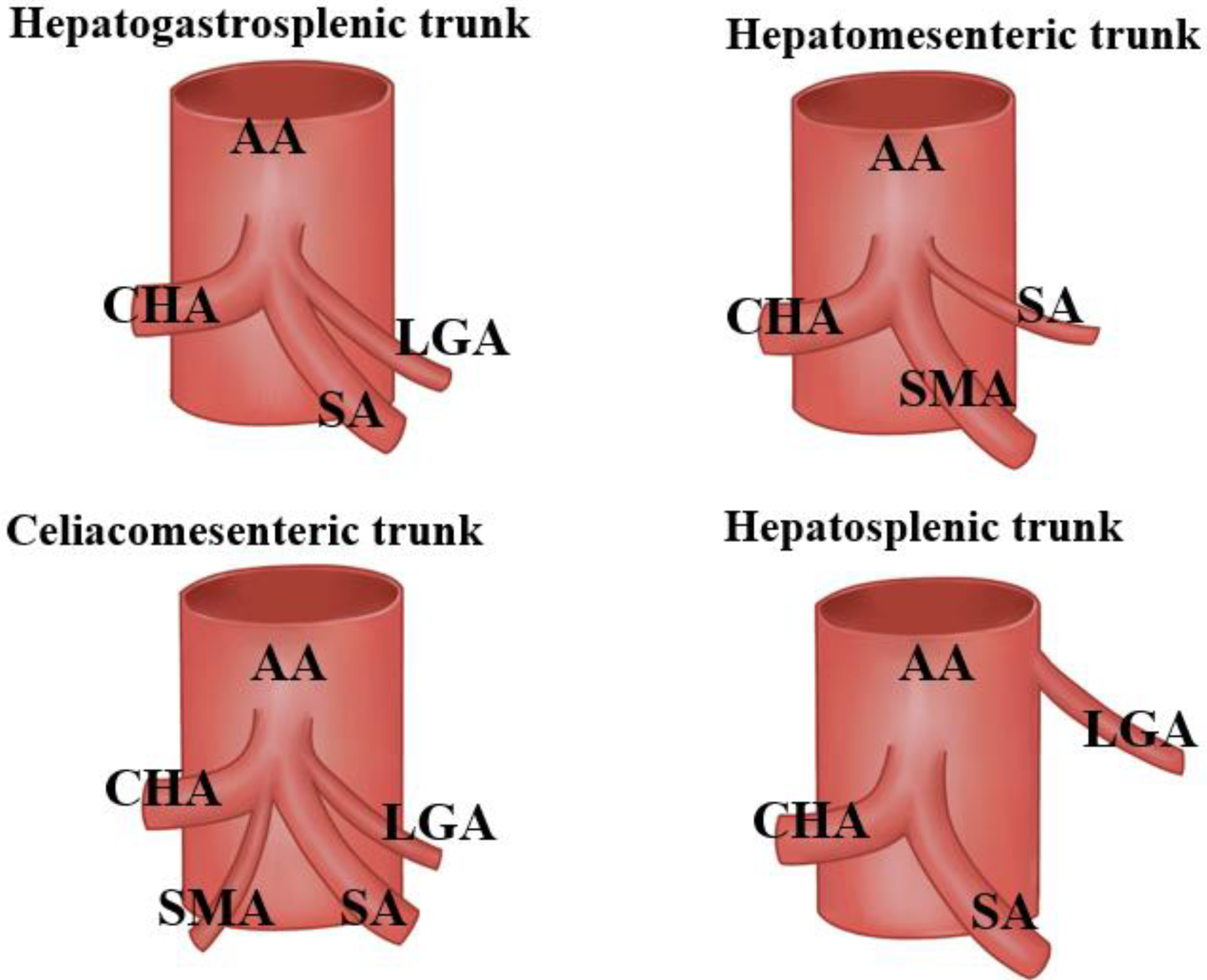

3.1. Variations at The Splenic Artery’s Origin

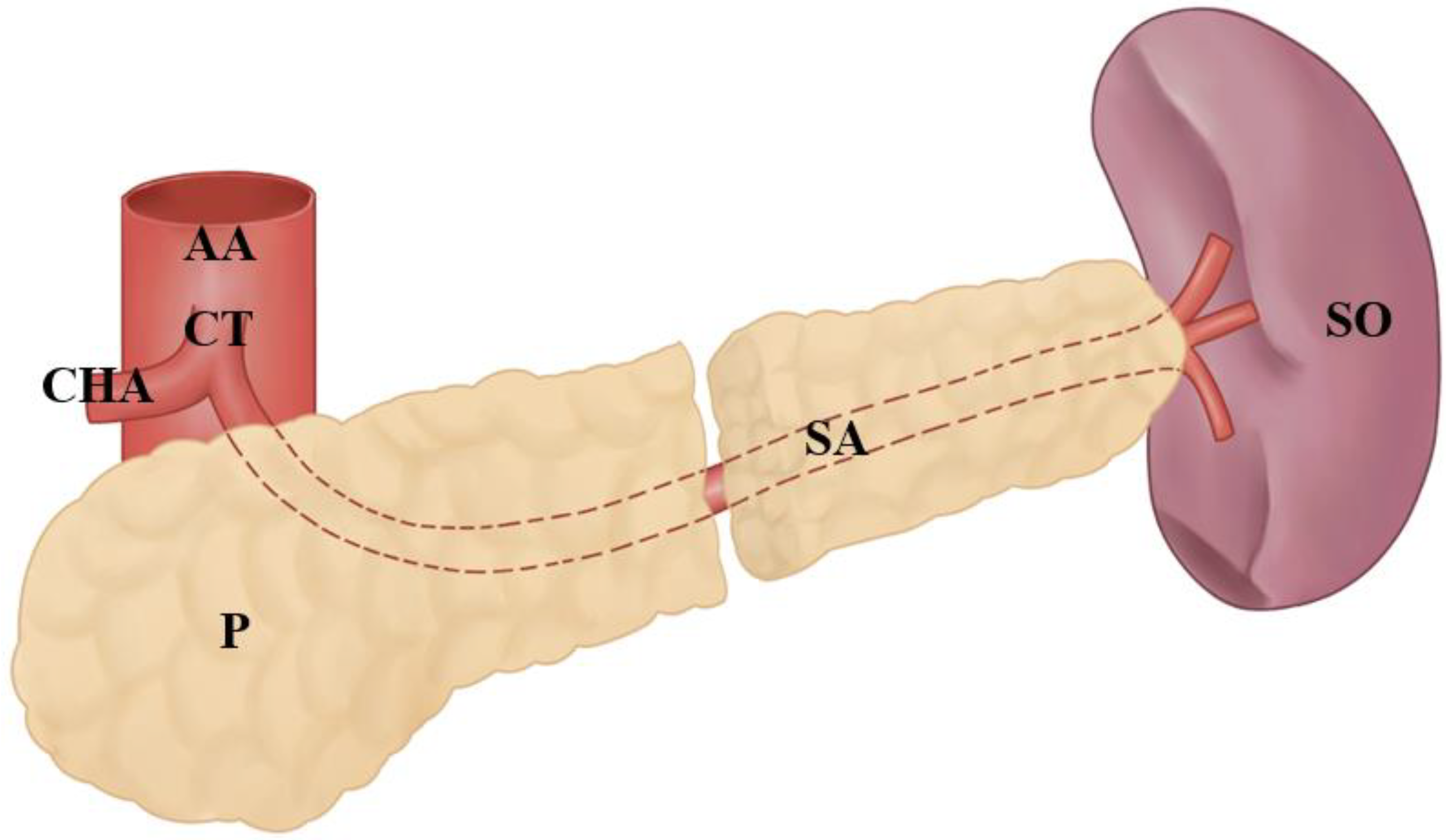

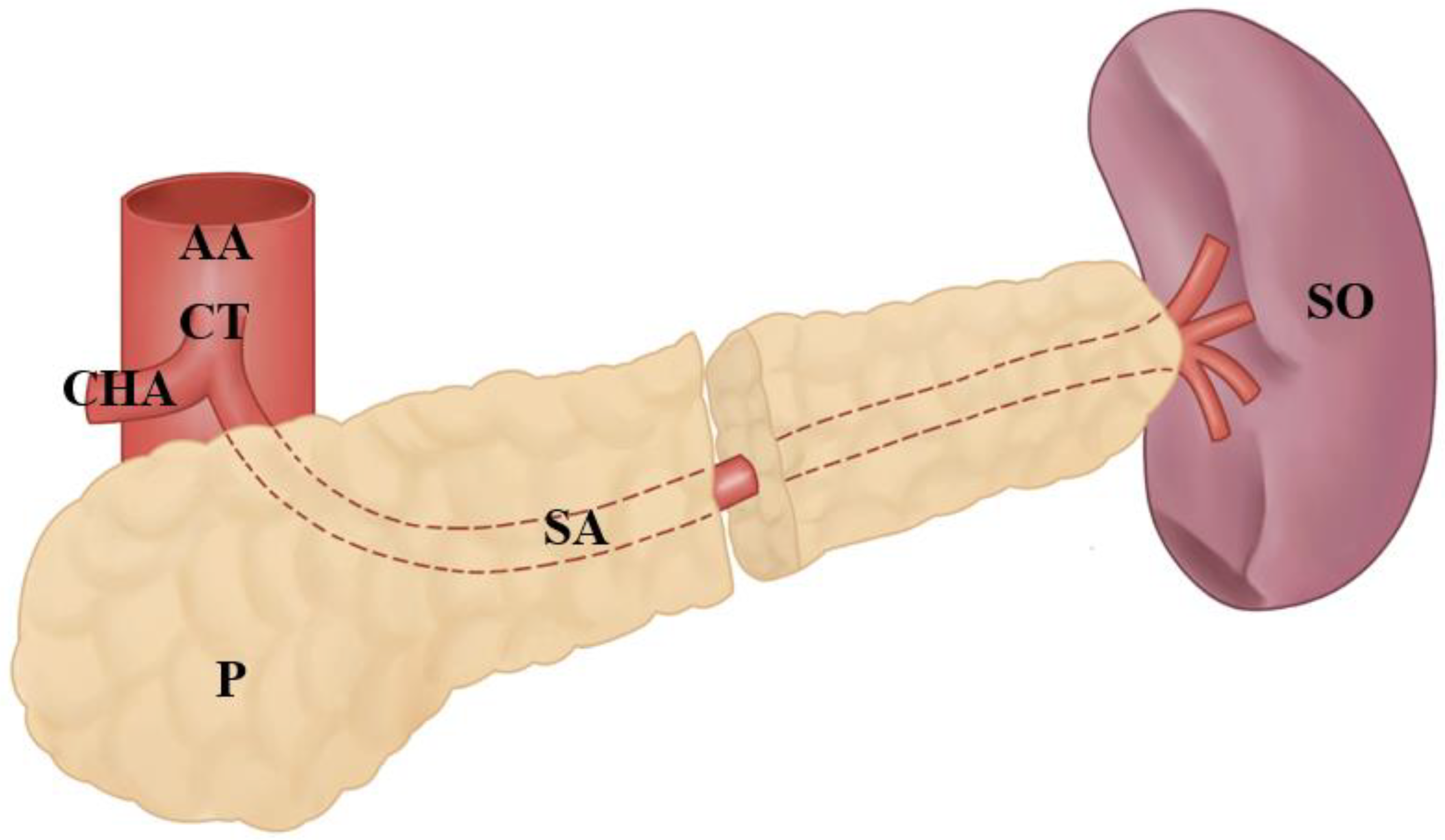

3.2. Variations in the Splenic Artery’s Trajectory

3.3. Splenic Artery’s Variations at the Entrance to the Splenic Hilum

3.4. Other Anatomical Variations of the Splenic Artery

3.5. Clinical Considerations

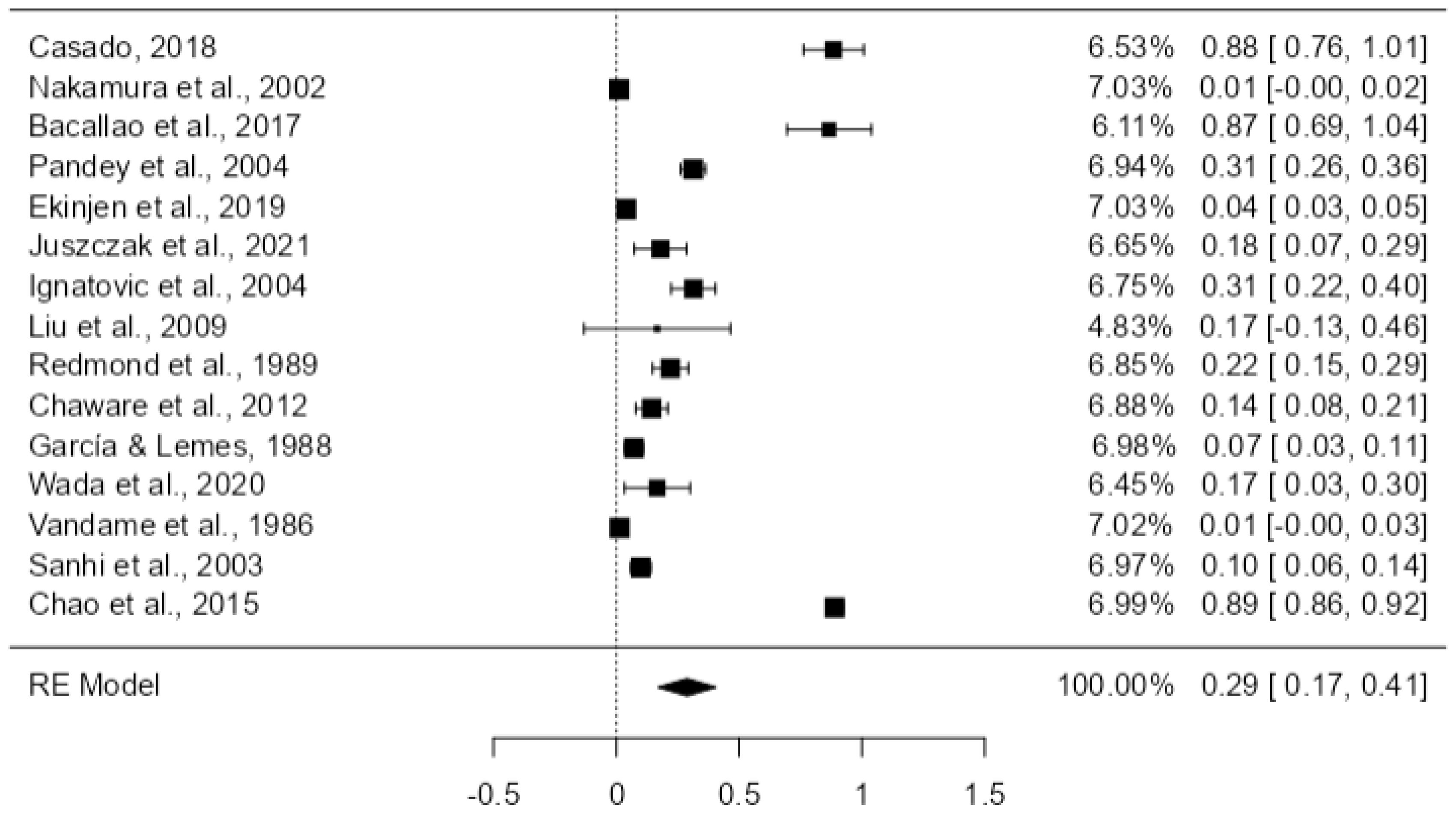

3.6. Quantitative Results

3.7. Surgical Clinical Correlation

3.8. Clinical Correlation with Diagnostic and Therapeutic Study

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sirio, M.; Herrera, N.; Rodríguez, M.; Antonetti, C. Contribución De La Ar-teria Esplénica En La Irrigación Del Bazo; Revista de la Facultad de Medicina; Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad Central de Venezuela: Caracas, Venezuela, 2023; Available online: http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0798-04692008000200003&lng=es (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Keith, L.M.; Agur, A.M.R.; Dalley, A.F. Clinically Oriented Anatomy 7E; Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Casado, M.; Rafael, P. Variantes Anatómicas De La Arteria Esplénica; Revista Médica Electrónica; Centro Provincial de Información de Ciencias Médicas de Matanzas—FCMM: Matanzas, Cuba, 1997; Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1684-18242018000200011&lng=es (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Hirai, Y.; Yamaki, K.-I.; Saga, T.; Hirata, T.; Yoshida, M.; Soejima, H.; Kanazawa, T.; Araki, Y.; Yoshizuka, M. An Anomalous Case of the Hepato-spleno-mesenteric and the Gastro-phrenic Trunks Independently Arising from the Abdominal Aorta. Kurume Med. J. 2000, 47, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ren, Z.F. Gastroduodenal-splenic trunk: An anatomical vascular variant. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2011, 52, 1385–1387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Mishra, R.; Shukla, V. Anatomical variations of the splenic artery and its clinical implications. Clin. Anat. 2004, 17, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susan, S.; Gray, H. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, M.; Levine, M. Textbook of Gastrointestinal Radiology; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, R.L.; Vogl, W.; Maw, M.; Gray, H.; Tibbitts, R.; Richardson, P. Gray’s Anatomy for Students; Elsevier: New Delhi, India, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Covantev, S.; Mazuruc, N.; Drangoi, I.; Belic, O. Unusual development of the celiac trunk and its clinical significance. J. Vasc. Bras. 2021, 20, e20200032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Mesa, J.; Domínguez Cordovés, J.; González Sosa, G.; Madrigal Batista, G.; Queral Gómez Quintero, R.; Collera Rodríguez, S.; Alfonso Sabatier, C.; de Armas Fernández, M.C. Aneurisma De La Arteria Esplénica; Revista Cubana de Cirugía; Editorial Ciencias Médicas: La Habana, Cuba, 2002; Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-74932008000200010 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Tomaszewski, K.; Henry, B.M.; Ramakrishnan, P.K.; Roy, J.; Vikse, J.; Loukas, M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Walocha, J.A. Development of the Anatomical Quality Assurance (AQUA) Checklist: Guidelines for reporting original anatomical studies. Clin. Anat. 2016, 30, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljahani, J.; Alaklabi, A.; Almalki, W.; Alfaleh, H.; Alzahrani, Y. Splenic artery arising from hepatic artery proper in a patient with celiacomesenteric trunk: A rare anatomical variant. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2019, 41, 1391–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Miyaki, T.; Hayashi, S.; Iimura, A.; Itoh, M. Three cases of the gastrosplenic and the hepatomesenteric trunks. Okajimas Folia Anat. Jpn. 2003, 80, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozan, H.; Önderoglu, S. Intrapancreatic course of the splenic artery with combined pancreatic anomalies. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 1997, 19, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacallao Cabreras, I.S.; Quesada Molina, D.; Fong Rodríguez, V.; Serrano González, L.M.; Cuba Yordi, O.L.; Almaguer Rodríguez, C. Comportamiento anatómico de la arteria lienal o esplénica en el humano. Rev. Arch. Médico Camagüey 2017, 21, 842–853. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Viswakumar, D.K.; Goriparthi, B.P. Anomalous Course of Accessory Splenic Arteries in Gastrosplenic Ligament: Case Report and Clinico-Embryological Basis. Acta Med. 2020, 63, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, M.; Kataria, R.; Bhatnagar, V.; Tandon, N.; Iyer, K.V.; Gupta, A.K.; Mitra, D.K. Intra-pancreatic splenic artery pseudoaneurysm. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 1998, 13, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, N.; Pusztai, A.M.; Miclăuş, G.D.; Pop, E.; Matusz, P. An anomalous origin of the gastrosplenic trunk and common hepatic artery arising independently from the abdominal aorta: A case report using MDCT angiography. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2018, 59, 353–357. [Google Scholar]

- Al Zahrani, Y.; AlMat’Hami, A.; Alobaidi, H.; Wiseman, D.; Mujoomdar, A. Accessory Right Hepatic Artery Arising from Splenic Artery Supplying Hepatocellular Carcinoma Identified by Computed Tomography Scan and Conventional Angiography: A Rare Anatomic Variant. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2017, 38, 316.e1–316.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, F.; Dondossola, D.; Fornoni, G.; Caccamo, L.; Rossi, G. Right hepatic artery from splenic artery: The four-leaf clover of hepatic surgery. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2016, 38, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facy, O.; Naouri, A.; Dugas, B.; Kadji, M.; Bernard, P.; Gabrielle, F. Anévrisme de l’artère splénique naissant de l’artère mésentérique supérieure: Stratégie thérapeutique. Ann. Chir. 2006, 131, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felli, E.; Wakabayashi, T.; Mascagni, P.; Cherkaoui, Z.; Faucher, V.; Pessaux, P. Aberrant splenic artery rising from the superior mesenteric artery: A rare but important anatomical variation. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2019, 41, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorello, B.; Corsetti, R. Splenic Artery Originating from the Superior Mesenteric Artery: An Unusual but Important Anatomic Variant. Ochsner J. 2015, 15, 476–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kanoun, H.; Boulanouar, D.; Djenas, M.; Ghecham, R.; Ben Ziada, N.; Rehimat, S.E.; Djamel, F.; Mehyaoui, R. Aneurysm of a splenic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery.About a case. Tunis. Med. 2018, 96, 317–320. [Google Scholar]

- Kervancioglu, S.; Yilmaz, F.G.; Gulsen, M. Massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding from an accessory splenic artery mimicking isolated gastric varices. Folia Morphol. 2013, 72, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, J. Atypical Arterial Supply to the Spleen by Polar Branches of Splenic Artery and Accessory Splenic Artery—A Case Report. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2014, 8, AD03–AD04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.R.; Lowe, S. Accessory Splenic Artery: A Rare Cause of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2017, 40, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Șelaru, M.; Rusu, M.C.; Jianu, A.M.; Bîrsășteanu, F.; Manta, B.A. Hepatomesenteric trunk, gastrosplenic trunk, coiled splenic and hepatic arteries, and a variant of Bühler’s arc. Folia Morphol. 2021, 80, 1032–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slaba, S.; Sfeir, S.; Nassar, J.; Noun, R.; Checrallah, A.; Tamraz, J. Variante originale de l’artère splénique. J. de Radiol. 2005, 86, 657–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaba, S.; Assaf, S. Aberrant gastroduodenal artery with splenic origin. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2018, 40, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, P.A.; Stewart, R.; Ellis, H. Tortuosity of the human splenic artery. Clin. Anat. 1995, 8, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Sol, M.; Ottone, N.E.; Vásquez, B. Tronco Hepato-Espleno-Mesentérico. Descripción de una Disposición Anómala del Tronco Celíaco. Int. J. Morphol. 2018, 36, 1525–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekingen, A.; Hatipoğlu, E.S.; Hamidi, C.; Tuncer, M.C.; Ertuğrul, Ö. Splenic artery angiography: Clinical classification of origin and branching variations of splenic artery by multi-detector computed tomography angiography method. Folia Morphol. 2020, 79, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juszczak, A.; Mazurek, A.; Walocha, J.A.; Pasternak, A. Coeliac trunk and its anatomic variations: A cadaveric study. Folia Morphol. 2021, 80, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.-H.; Xu, M.; Huang, C.-M.; Li, P.; Xie, J.-W.; Wang, J.-B.; Lin, J.-X.; Lu, J.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Cao, L.-L.; et al. Anatomy and influence of the splenic artery in laparoscopic spleen-preserving splenic lymphadenectomy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8389–8397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Aoki, T.; Murakami, M.; Fujimori, A.; Koizumi, T.; Kusano, T.; Matsuda, K.; Nogaki, K.; Hakozaki, T.; Shibata, H.; et al. Individualized procedures for splenic artery dissection during laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. BMC Surg. 2020, 20, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, J.; Bonte, J. Systematisation of the Arteries in the Splenic Hilus. Cells Tissues Organs 1986, 125, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daisy Sahni, A.; Indar Jit, B.; Gupta, C.N.M.; Gupta, D.M.; Harjeet, E. Branches of the splenic artery and splenic arterial segments. Clin. Anat. 2003, 16, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaware, P.N.; Belsare, S.M.; Kulkarni, Y.R.; Pandit, S.V.; Ughade, J.M. Variational Anatomy of the Segmental Branches of the Splenic Artery. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2012, 6, 336–338. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Porrero, J.; Lemes, A. Arterial Segmentation and Subsegmentation in the Human Spleen. Cells Tissues Organs 1988, 131, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatovic, D.; Stimec, B.; Zivanovic, V. The basis for splenic segmental dearterialization: A post-mortem study. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2004, 27, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Lu, J.P.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Jin, A.G.; Wang, J.; Tian, J.M. Detection of anomalous splenic artery aneurysms with three-dimensional contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Abdom. Imaging 2008, 34, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, H.P.; Redmond, J.M.; Rooney, B.P.; Duignan, J.P.; Bouchier-Hayes, D.J. Surgical anatomy of the human spleen. Br. J. Surg. 1989, 76, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Cochrane Training: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Greenhalgh, T. How to read a paper: Assessing the methodological quality of published papers. BMJ 1997, 315, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDermid, J.C.; Walton, D.M.; Avery, S.; Blanchard, A.; Etruw, E.; McAlpine, C.; Goldsmith, C.H. Measurement Properties of the Neck Disability Index: A Systematic Review. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2009, 39, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, A.B., II. Das Arteriensystem Der Japaner; Hasebe, K., Kyoto, T.D., Eds.; Kaiserlich-Japanische Universitat: Kyoto, Japan, 1928; pp. 20–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Yano, R.; Emura, S.; Shoumura, S. Anatomic variation of the celiac trunk with special reference to hepatic artery patterns. Ann. Anat.-Anat. Anz. 2009, 191, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankar, K.D.; Bhanu, P.S.; Susan, P.J. Variant Anatomy of the Celiac Trunk and its Branches. Int. J. Morphol. 2011, 23, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukas, M.; Fergurson, A.; Louis, R.G.; Colborn, G.L. Multiple variations of the hepatobiliary vasculature including double cystic arteries, accessory left hepatic artery and hepatosplenic trunk: A case report. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2006, 28, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, N.A. Variational anatomy of the hepatic, cystic, and retroduodenal arteries. A.M.A. Arch. Surg. 1953, 66, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirasanagandla, S.R.; Kumar, N.; Shetty, S.D.; Badagabettu, S.N. Hepatosplenic Trunk Associated with Tortuous Course of Right Hepatic Artery Forming Caterpillar Hump. North Am. J. Med. Sci. 2012, 4, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolintineanu, L.A.; Costea, A.N.; Iacob, N.; Pusztai, A.M.; Pleş, H.; Matusz, P. Hepato-spleno-mesenteric trunk, in association with an accessory left hepatic artery, and common trunk of right and left inferior phrenic arteries, independently arising from left gastric artery: Case report using MDCT angiography. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2019, 60, 1323–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Panagouli, E.; Venieratos, D.; Lolis, E.; Skandalakis, P. Variations in the anatomy of the celiac trunk: A systematic review and clinical implications. Ann. Anat.-Anat. Anz. 2013, 195, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemanth, K.; Garg, S.; Yadav, T.D.; Sahni, D.; Singh, R. Hepato-gastro-phrenic trunk and hepato-spleno-mesenteric trunk: A rare anatomic variation. Trop. Gastroenterol. 2011, 32, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, K.S.; Pamidi, N.; Vollala, V.R.; Bolla, S.R. Hepato-spleno-mesenteric trunk: A case report. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2010, 51, 401–402. [Google Scholar]

- Poynter, C.W.M.; Hicks, J.D. Congenital Anomalies of the Arteries and Veins of the Human Body: With Bibliography, 1st ed.; The University Studies of the University of Nebraska: Lincoln, NE, USA, 1922; Volume 22, p. 106. [Google Scholar]

- Michels, N.A. The variational anatomy of the spleen and splenic artery. Am. J. Anat. 1942, 70, 21–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros Viamontes, G.; Durán Matos, M.; Almaguer Rodríguez, C. Variantes anatómicas de las arterias que irrigan al estómago. Revisión bibliográfica. Rev. Arch. Médico Camagüey 2001, 5, 346–359. [Google Scholar]

- Higashi, N.; Hirai, K. A case of the three branches of the celiac trunk arising directly from the abdominal aorta. Anat. Sci. Int. 1995, 70, 349–352. [Google Scholar]

- Raikos, A.; Paraskevas, G.K.; Natsis, K.; Tzikas, A.; Njau, S.N. Multiple variations in the branching pattern of the abdominal aorta. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2010, 51, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Losanoff, J.E.; Millis, M.J.; Harland, R.C.; Testa, G. Hepato-spleno-mesenteric trunk. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2007, 204, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmalath, K.; Ramesh, B.R.; Balachandra, N.; Mamatha, Y. Accessory splenic artery from left gastric artery from the left gastric artery. Int. J. Anat. Var. 2010, 3, 106–107. [Google Scholar]

- Iacob, N.; Sas, I.; Joseph, S.C.; Pleş, H.; Miclăuş, G.D.; Matusz, P.; Tubbs, R.S.; Loukas, M. Anomalous pattern of origin of the left gastric, splenic, and common hepatic arteries arising independently from the abdominal aorta. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2014, 55, 1449–1453. [Google Scholar]

- Covantsev, S.; Alieva, F.; Mulaeva, K.; Mazuruc, N.; Belic, O. Morphological Evaluation of the Splenic Artery, Its Anatomical Variations and Irrigation Territory. Life 2023, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manatakis, D.K.; Piagkou, M.; Loukas, M.; Tsiaoussis, J.; Delis, S.G.; Antonopoulos, I.; Chytas, D.; Natsis, K. A systematic review of splenic artery variants based on cadaveric studies. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2021, 43, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Study Design | Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Domain 3 | Domain 4 | Domain 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aljahani, 2019 [13] | Case study | Low | High | High | High | High |

| Casado et al., 2018 [3] | Descriptive study (26 specimens) | Low | Low | High | High | Unclear |

| Nakamura et al., 2002 [14] | Retrospective study (275 specimens) | Low | Low | Low | High | Unclear |

| Ozan and Onderoglu., 1997 [15] | Case study | Low | High | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Bacallao et al., 2017 [16] | Observational descriptive study (15 specimens) | Low | Low | Low | High | Unclear |

| Ramakrishnan et al., 2020 [17] | Case study | Low | High | Low | High | Unclear |

| Srinivas et al., 1998 [18] | Case study | Low | High | Low | High | High |

| Iacob et al., 2018 [19] | Case study | Low | Low | High | High | High |

| Al Zahrani, 2016 [20] | Case study | Low | Low | High | High | High |

| Caruso, 2016 [21] | Case study | Low | Low | Low | High | High |

| Facy, 2006 [22] | Case study | Low | Low | High | High | High |

| Felli, 2019 [23] | Case study | Low | Low | Low | High | High |

| Fiorello, 2015 [24] | Case study | Low | Low | High | High | High |

| Kanoun, 2018 [25] | Case study | Low | Low | High | Low | High |

| Kervancioglu, 2013 [26] | Case study | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

| Kumar, 2014 [27] | Case study | Low | Low | High | High | High |

| Li and Ren. 2011 [5] | Case study | Low | High | High | High | Unclear |

| Pandey, 2004 [6] | Descriptive study (320 specimens) | Low | Low | Low | High | Unclear |

| Patel, 2017 [28] | Case study | Low | Low | High | High | Low |

| Selaru, 2020 [29] | Case study | Low | High | Low | High | Low |

| Slaba, 2005 [30] | Case study | Low | High | Low | High | Unclear |

| Slaba, 2018 [31] | Case study | Low | High | High | High | Unclear |

| Sylvester, 1995 [32] | Descriptive (29 specimens) | Low | Low | Low | High | Unclear |

| Del sol et al., 2018 [33] | Case study | Low | Low | High | High | Low |

| Ekingen et al., 2019 [34] | Retrospective study | High | High | High | Low | Low |

| Juszczak et al., 2021 [35] | Case series | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Zheng et al., 2015 [36] | Retrospective study | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Wada et al., 2020 [37] | Retrospective study | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Vandamme et al., 1986 [38] | Case series | High | High | High | Low | High |

| Daisy et al., 2003 [39] | Case series | Low | Low | High | Unclear | Low |

| Chaware et al., 2012 [40] | Case series | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| García-Porrero and Lemes, 1988 [41] | Case series | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ignjatovic et al., 2004 [42] | Case series | Low | Low | High | Low | Low |

| Liu et al., 2009 [43] | Case series | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Redmond et al., 1989 [44] | Case series | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| References | Study Design | Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Domain 3 | Domain 4 | Domain 5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | ||

| Aljahani, 2019 [13] | Case study | NA | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | NA | Y | Y | N A | Y |

| Casado et al., 2018 [3] | Descriptive study | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | U | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | NA | Y | N A | N A | U |

| Nakamura et al., 2002 [14] | Retrospective study | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | U |

| Ozan and Onderoglu., 1997 [15] | Case study | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | U | U | NA | U |

| Bacallao et al., 2017 [16] | Observational and descriptive study | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | NA | U |

| Ramakrishnan et al., 2020 [17] | Case study | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | NA | U |

| Srinivas et al., 1998 [18] | Case study | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | U | N | U | NA | U |

| Iacob et al., 2018 [19] | Case study | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y |

| Al Zahrani, 2016 [20] | Case study | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA | Y |

| Caruso, 2016 [21] | Case study | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y |

| Facy, 2006 [22] | Case study | y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA | Y |

| Felli, 2019 [23] | Case study | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA | Y |

| Fiorello, 2015 [24] | Case study | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA | Y |

| Kanoun, 2018 [25] | Case study | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | NA | Y | Y |

| Kervancioglu, 2013 [26] | Case study | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | NA | Y | Y |

| Kumar, 2014 [27] | Case study | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | N | Y |

| Li and Ren. 2011 [5] | Case study | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | NA | N | U |

| Pandey, 2004 [6] | Descriptive study | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | NA | NA | U |

| Patel, 2017 [28] | Case study | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | NA | N |

| Selaru, 2020 [29] | Case study | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | NA | N |

| Slaba, 2005 [30] | Case study | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | U | U | NA | U |

| Slaba, 2018 [31] | Case study | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | N | U |

| Sylvester, 1995 [32] | Descriptive study | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | NA | NA | U |

| Del sol et al., 2018 [33] | Case study | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | NA | N |

| Ekingen et al., 2019 [34] | Retrospective study | Y | Y | Y | H | Y | Y | Y | Y | H | Y | N | Y | N | Y | H | Y | Y | Y | NA | L | Y | Y | Y | NA | L |

| Juszczak et al., 2021 [35] | Case series | Y | N | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | N | N | N | Y | L | N | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | NA | L |

| Zheng et al., 2015 [36] | Retrospective study | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | N | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Wada et al., 2020 [37] | Retrospective study | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | N | Y | N | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Vandamme et al., 1986 [38] | Case series | N | Y | N | H | N | Y | N | Y | H | N | N | N | N | Y | H | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | N | N | Y | Y | H |

| Daisy et al., 2003 [39] | Case series | N | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | N | N | N | N | Y | H | N | Y | Y | N | U | N | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Chaware et al., 2012 [40] | Case series | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | N | N | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | N | Y | Y | Y | L |

| García-Porrero and Lemes, 1988 [41] | Case series | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | N | N | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Ignjatovic et al., 2004 [42] | Case series | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | N | N | N | Y | H | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Liu et al., 2009 [43] | Case series | N | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Redmond et al., 1989 [44] | Case series | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L | Y | Y | Y | Y | L |

| Author, Year | Type of Study and Sample (n) | Incidence and Type of Variation | Country/Geographic Region | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casado, 2018 [3] | Descriptive (26 specimens) | Total 31% variations in origin; 15.4% with a straight path; 42.3% relationship with the splenic vein in the arrival to the spleen (posterior). | Cuba/North America | Total of 17 (65.4%) men and 9 (34.6%) women |

| Aljahani, 2019 [13] | Case study | Mesenteric celiac trunk | Saudi Arabia/Asia | One male |

| Nakamura et al., 2002 [14] | Retrospective study (275 cadavers) | Total 1.1% hepatomestric and gastrosplenic trunk | Japan/Asia | Not specified |

| Ozan and Onderoglu, 1997 [15] | Case study | Intrapancreatic course of the splenic artery | Turkey/Europe | One male |

| Bacallao et al., 2017 [16] | Descriptive observational study (15 anatomical preparations, 5 adults and 10 fetuses) | A total of 40% of adult cadavers originating from the abdominal aorta; 40% of specimens with a straight path; 10% of fetuses originating from the abdominal aorta. | Cuba/North America | Not specified |

| Ramakrishnan et al., 2020 [26] | Case study | Abnormal course of accessory splenic arteries | India/Asia | One male |

| Srinivas et al., 1998 [18] | Case study | Intrapancreatic splenic artery | India/Asia | One male |

| Iacob et al., 2018 [19] | Case study | Gastrosplenic trunk | Romania/Europe | One female |

| Al Zahrani, 2016 [20] | Case study | Accessory right hepatic artery originating from the splenic artery | Saudi Arabia/Asia | One male |

| Caruso, 2016 [21] | Case study | Right hepatic artery originating from splenic artery | Italy/Europe | Not specified |

| Facy, 2006 [22] | Case study | Splenic artery originating from superior mesenteric artery | France/Europe | One male |

| Felli, 2019 [23] | Case study | Splenic artery originating from superior mesenteric artery | France/Europe | One female |

| Fiorello, 2015 [24] | Case study | Splenic artery originating from superior mesenteric artery | USA/North America | One male |

| Kanoun, 2018 [25] | Case study | Splenic artery originating from superior mesenteric artery | Algeria/Africa | Not specified |

| Kervancioglu, 2013 [26] | Case study | Accessory splenic artery | Turkey/Europe | One male |

| Kumar, 2014 [27] | Case study | Accessory splenic artery | India/Asia | Not specified |

| Li and Ren. 2011 [5] | Case study | Origin in the splenic gastroduodenal trunk | China/Asia | One male |

| Pandey, 2004 [6] | Descriptive study (320 specimens) | Total 8.1% origin in the abdominal aorta; 18.4% anteropancreatic course; 2.6% retropancreatic course; 4.8% intrapancreatic course. | India/Asia | Total of 264 (82.5%) males, 56 (17.5%) females |

| Patel, 2017 [28] | Case study | Accessory splenic artery | USA/North America | One male |

| Selaru, 2020 [29] | Case study | Gastrosplenic trunk | Romania/Europe | One female |

| Slaba, 2005 [30] | Case study | Splenic artery duplication | France/Europe | One female |

| Slaba, 2018 [31] | Case study | Origin in abdominal aorta | France/Europe | One female |

| Sylvester, 1995 [32] | Descriptive study (29 specimens) | Crookedly | England/Europe | A total of 13 (44.8%) females; 16 (55.2%) males |

| Del sol et al., 2018 [33] | Case study | Hepatosplenomesenteric trunk | Chile/South America | One male |

| Ekingen et al., 2019 [34] | Descriptive observational study (750 patients) | The SA as a branch of the CT bifurcation in 510 (68.00%) cases, of the CT trifurcation in 82 (10.94%) cases, of the CT quadrifurcation in 3 (0.40%) cases, of the CT pentafurcation in 1 (0.13%) case; 30 (4%) hepatosplenic trunk (HST); 5 (0.67%) HST and divided into replaced left gastric artery (RLGA). | Turkey/Europe | Total of 276 (45.87%) female, 320 (54.13%) male |

| Juszczak et al., 2021 [35] | Descriptive observational study (50 cadavers) | Celiac trunk divided into CHA, LGA, and SA in 82% of the cadavers (41/50), Adachi type I. In the classical type, CHA, SA, and LGA were found to arise from the CT. This was found in 20% of dissections (8/41). | Poland/Europe | Fifty formalin-fixed abdomen specimens |

| Zheng et al., 2015 [36] | Descriptive observational study (317 patients) | The anatomical data showed that 64.7% of the patients had the concentrated type (205 cases) and 35.3% had the distributed type (112 cases); 22 cases (6.9%) single branch SA type; 250 cases (78.9%) 2-branched type; 43 cases (13.6%) 3-branched type; 2 cases (0.6%) of a multiple-branched SA type. | China/Asia | Total of 317 patients with upper- or middle-third gastric cancer underwent splenic hilar lymphadenectomy (LTGSPL) |

| Wada et al., 2020 [37] | Descriptive study | Total of 25 (83%) cases with type S (curves and runs suprapancreatic) and 5 (17%) with type D (runs straight and dorsal to the pancreas) SA anatomy | Japan/Asia | Total of 25 males in the type S group with an average age of 67.4 (19–86) years old and 5 males in the type D group with an average age of 58.8 (47–81) years old |

| Vandamme et al., 1986 [38] | Descriptive study | Total of 26% had a left gastroomental artery (LGOA) emerging from it and in 8% the SA divided simultaneously into two splenic rami and the LGOA; 66% of the splenic inferior and left gastroomental artery arose from a common splenicocogastroomentalis trunk; 2 cases showed a voluminous anastomosis between the arteria extremitatis lienalis posterioris and a splenic branch. | Belgium/Europe | Total of 156 abdominal preparations. No age or gender-related information was described |

| Daisy et al., 2003 [39] | Descriptive study | In 68% of specimens, the LGA arose as the first branch of the CT that then bifurcated into the CHA and SPLA. In 30% of dissections the CT divided into three branches at the same point. In the remaining 2% the SA and the LGA arose by a common trunk from the CT and the SA coursed retroperitoneally. | India/Asia | Total of 156 male and 44 female adults (18–80 years of age) |

| Chaware et al., 2012 [40] | Descriptive study | Total of 95 (85.58%) had two primary branches and 16 (14.42%) showed three primary branches. Polar branches were seen in 92 specimens. | India/Asia | Total of 15 female spleens and 96 male spleens; however, they did not consider gender for the statistical analysis |

| García-Porrero and Lemes, 1988 [41] | Descriptive study | In 92% the SA divided into 2 primary branches: superior and inferior. In the remaining 7.18% it divided into 3 branches: superior, middle, and inferior. The presence of 3 primary branches was found in 3.76% of males and in 16% of females (p < 0.001). | Spain/Europe | Total of 133 male and 48 female cadaveric specimens |

| Ignjatovic et al., 2004 [42] | Descriptive study | The superior terminal splenic branch divided extracapsularly into 2.8 ± 0.9 (range 2–5) and the inferior terminal splenic branch into 2.3 ± 0.75 (range 2–5) branches per sample. | Serbia/Europe | Total of 53 male cadavers, 49 female cadavers with a mean age of 54 years (range 26–83 years). |

| Liu et al., 2009 [43] | Case series | Six patients with an SA arising anomalously from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). The SA arose anomalously from the root of the superior mesenteric artery; the celiac trunk did not arise from any branches supplying the spleen and the hepatic artery arose from the abdominal aorta alone. | China/Asia | Total of 4 females and 2 male patients ranging in age from 37 to 71 years with a mean of 49.7 years |

| Redmond et al., 1989 [44] | Descriptive study | The SA arose as a single trunk from the celiac axis in 99.22%, and 0.78% was found arising directly from the aorta and supplying the upper pole; 97.63% had a suprapancreatic course, but in 2 (1.57%) cases it was retropancreatic and in 1 (0.78%) case it was intrapancreatic. | Ireland/Europe | Total of 127 human spleens were studied, of which 50 were fresh post-mortem specimens; the remaining 77 were from dissection room cadavers. |

| Author, Year | Type of Anatomical Variation | Clinical Considerations | Sample Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casado et al., 2018 [3] | Anatomical variations in the origin of the splenic artery:

| The anatomical knowledge of the varieties of the celiac trunk and the splenic artery is of paramount importance for the surgical approach of the supramesocolonic region. | Total of 26 blocks from cadavers without abdominal surgeries or hematological diseases. |

| Nakamura et al., 2002 [14] | Gastrosplenic trunk arising from the celiac trunk | The variation of the three branches of the celiac trunk is important for the arterial supply of the digestive organs of the upper abdomen. Three cases of gastrosplenic and hepatomesenteric trunks in Japanese cadavers were presented in this study. Especially, in case 1, the left inferior phrenic artery arose from the gastrosplenic trunk and the left hepatic artery arose from the left gastric artery. | Three specimens |

| Bacallao et al., 2017 [16] | Splenic artery origin and pathway | The origin of the vessel from the celiac trunk with a tortuous trajectory and direction to the upper edge of the pancreas, where it is related to the homonymous vein, the anterior face of the kidney, and the left adrenal gland. Collateral branches: dorsal pancreatic, pancreatic, and left gastroepiploic, with variation in number and origin in fetuses. | Total of 15 anatomical preparations, 5 of adult humans (3 of the male sex and 2 of the female sex), aged e between 48 and 63 years; 10 human fetuses, between 20 and 29 weeks of age, 6 female and 4 males. |

| Pandey, 2004 [6] | Variations in the origin, course, and pattern of terminal branching of the splenic artery | Of 320 cadavers, the splenic artery originated from the celiac trunk in most of cadavers (90.6%), followed by the abdominal aorta (8.1%), and other views (1.3%). A suprapancreatic course of the artery was commonly observed (74.1%), followed by enteropancreatic (18.5%), intrapancreatic (4.6%), and retropancreatic (2.8%) courses. | Unspecified sex and age. |

| Sylvester, 1995 [32] | Tortuous splenic artery | The splenic artery tortuosity index was evaluated in 29 cadaver samples and 44 celiac angiograms. This index is achieved by measuring the straight distance from the origin of the splenic artery, from the celiac trunk to the beginning of the hilar branches as well as the total length of the artery between these two points. | Patients: 29 Age and sex: not specified. |

| Ekingen et al., 2019 [34] | Total of 596 (79.47%; 276 females and 320 males) normal anatomy of the SA | No clinical correlation was made, but a classification of the SA variations was given. | Patients: 750 patients Gender: 276 (45.87%) female, 320 (54.13%) male. Age: 16–93 years (50.6 ± 16.2). |

| Juszczak et al., 2021 [35] | Celiac trunk divided into CHA, LGA, and SA in 82% of the cadavers (41/50), Adachi type I. A classical or “true” tripod called “tripus Halleri” and a non-classical type. In the classical type, CHA, SA, and LGA were found to arise from the CT. This was found in 20% of dissections (8/41). | No clinical correlation was made but comment that this study may have implications for surgical interventions and imaging studies related to the abdominal region. | Fifty formalin-fixed abdomen specimens; the sex and age were not taken into account. |

| Zheng et al., 2015 [36] | The anatomical data showed that 64.7% of the patients had the concentrated type (205 cases) and 35.3% had the distributed type (112 cases); 22 cases (6.9%) single branch SA type (SA passes tortuously through the splenic hilar without dividing into terminal branches), 250 cases (78.9%) of the 2-branched type (the SA divides into the superior and inferior lobar arteries); 43 cases (13.6%) of the 3-branched type (the SA divides into the superior, middle, and inferior lobar arteries of the spleen), and 2 cases (0.6%) of a multiple-branched SA type (the SA branches into 4–7 branches that enter the splenic hilum). | Patient intraoperative characteristics: For all 317 patients, the mean surgical time was 175.41 ± 31.97 min (range, 120–420 min). The mean total blood loss was 53.94 ± 31.77 mL (range, 5–300 mL). The mean number of harvested No. 10 LNs was 2.69 ± 2.16 (range, 0–9). The mean splenic hilar lymphadenectomy time (23.15 ± 8.02 vs. 26.21 ± 8.84 min; p = 0.002), mean blood loss resulting from splenic hilar lymphadenectomy (14.78 ± 11.09 vs. 17.37 ± 10.62 mL; p = 0.044), number of vascular clamps used at the splenic hilum (9.64 ± 2.88 vs. 10.40 ± 3.57; p = 0.040), and mean total number of retrieved LNs (40.36 ± 14.08 vs. 44.46 ± 14.80; p = 0.015). | Total of 317 patients with upper- or middle-third gastric cancer underwent splenic hilar lymphadenectomy (LTGSPL); neither sex nor age were described. |

| Wada et al., 2020 [37] | There were 25 (83%) cases with type S and 5 (17%) with type D splenic artery anatomy. | The mean total operative time was 189 (range, 85–270) min and intraoperative blood loss was 156 (range, 5–810) mL. None of the patients suffered from grade C postoperative pancreatic fistula. The mean postoperative hospital stay was 16.1 (8–48) days, and there was no perioperative mortality. In 25 (83%) patients, the splenic artery was successfully dissected using the planned surgical procedure, whereas the surgical plan had to be altered in 5 cases (17%). | Total of 25 males in the type S group, with an average age of 67.4 (19–86) years old, and 5 males in the type D group, with an average age of 58.8 (47–81) years old. |

| Vandamme et al., 1986 [38] | Total of 156 abdominal preparations were explored by angiography, corrosion, and dissection; 26% of the preparations had a left gastroomental artery (LGOA) emerging from them and in 8% the SA divides simultaneously into two splenic rami and the LGOA; in the remaining 66% the splenic inferior and left gastroomental artery arose from a common splenicocogastroomentalis trunk. | No clinical correlation was made. | Total of 156 abdominal preparations. Neither age nor gender-related information was described. |

| Daisy et al., 2003 [39] | Total of 200 cadavers. In 90% of instances, the SPLA was the largest of the three branches; in the remaining specimens, the CHA was the largest. In 68% of specimens, the LGA arose as the first branch of the CT that then bifurcated into the CHA and SPLA. In 30% of dissections the CT divided into three branches at the same point. Total of 5 of 44 (79.4%) female specimens. It arose from the lower lobar artery (LLA). In one instance, it was a branch of the SPB. Tortuosity was present only in 10% of adults. | No concrete clinical correlation was made. | Total of 156 male and 44 female adults (18–80 years of age). |

| Chaware et al., 2012 [40] | Total of 111 cadaveric specimens were used: 95 (85.58%) had two primary branches and 16 (14.42%) showed three primary branches. Polar branches were seen in 92 specimens. The superior polar branch was present in 32 (28.82%) specimens, the inferior polar branch was present in 47 (42.34%) specimens, both the superior and inferior branches were present in 13 (11.71%) specimens, and no polar branch was observed in 19 (17.11%) of the total spleens. | Discusses that detailed knowledge of the segmental branches of the SA is crucial due to the tendency of surgeons to conserve as much splenic tissue as possible during splenectomy, but it does not establish a statistical correlation between the anatomic variants of the SA and the splenectomy’s possible outcomes/complications. | Total of 15 female spleens and 96 male spleens; however, gender is not considered for the statistical analysis. |

| García-Porrero and Lemes, 1988 [41] | Total of 181 cadaveric specimens were dissected. For 92% of the dissected cases studied, the SA divided into 2 primary branches, superior and inferior. In the remaining 7.18% the SA divided into 3 branches: superior, middle, and inferior. | No clinical correlation was made. | Total of 133 male and 48 female cadaveric specimens. |

| Ignjatovic et al., 2004 [42] | Total of 102 consecutive fresh autopsy specimens. A superior terminal splenic branch (STSB) divided extracapsularly into 2.8 ± 0.9 branches per sample. The distribution of branches was as follows: two (44 cases), three (36 cases), four (17 cases), and five (5 cases). | This implies that the operative technique for splenic lobe/segment dearterialization, previously described for the inferior polar segment and the inferior splenic lobe, could find further use in new circumstances and provide more secure spleen preservation through the ligation/dearterialization of individual segmental arteries. The technique seems to encompass both the benefits and drawbacks of splenic vascular organization. | Total of 53 male cadavers and 49 female cadavers with a mean age of 54 years (range 26–83 years). |

| Liu et al., 2009 [43] | Six patients with aneurysms involving the splenic artery arising anomalously from the superior mesenteric artery were detected with 3D CE-MRA. The SA arose anomalously from the root of the superior mesenteric artery, the celiac trunk did not arise from any branches supplying the spleen, and the hepatic artery arose from the abdominal aorta alone. | Two patients underwent open vascular surgery, an endovascular procedure was performed on three (1 coil embolization with gelform and glue and 2 stent graft placements), and one patient refused treatment and was lost to follow-up. | Four female and two male patients ranging in age from 37 to 71 years with a mean of 49.7 years. |

| Redmond et al., 1989 [44] | Total of 127 human spleens were studied. The SA arose as a single trunk from the celiac axis in all but one case, where a second splenic artery was found arising directly from the aorta and supplying the upper pole. | No clinical correlation was made. | Total of 127 human spleens were studied, of which 50 were fresh post-mortem specimens; the remaining 77 were from dissection room cadavers. |

| Random-Effects Model (k = 15) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | se | Z | p | CI Lower Bound | CI Upper Bound | |

| Intercept | 0.288 | 0.0598 | 4.82 | <0.01 | 0.171 | 0.405 |

| Heterogeneity Statistics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tau | Tau² | I² | H² | R² | df | Q | p |

| 0.225 | 0.0508 (SE = 0.0377) | 99.48% | 192.813 | 14.000 | 2699.384 | <0.01 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valenzuela-Fuenzalida, J.J.; Martínez-Hernández, D.; Pérez-Jiménez, D.; Baeza, P.N.; Becerra-Farfan, Á.; Orellana-Donoso, M.; Mejias, A.B.; Syed, Q.H.; Luengo, M.R.; Iwanaga, J. Prevalence and Clinical Consideration of Anatomical Variants of the Splenic Artery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13063510

Valenzuela-Fuenzalida JJ, Martínez-Hernández D, Pérez-Jiménez D, Baeza PN, Becerra-Farfan Á, Orellana-Donoso M, Mejias AB, Syed QH, Luengo MR, Iwanaga J. Prevalence and Clinical Consideration of Anatomical Variants of the Splenic Artery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(6):3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13063510

Chicago/Turabian StyleValenzuela-Fuenzalida, Juan José, Daniela Martínez-Hernández, Daniela Pérez-Jiménez, Pablo Nova Baeza, Álvaro Becerra-Farfan, Mathias Orellana-Donoso, Alejandro Bruna Mejias, Qareen Hania Syed, Macarena Rodriguez Luengo, and Joe Iwanaga. 2023. "Prevalence and Clinical Consideration of Anatomical Variants of the Splenic Artery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Applied Sciences 13, no. 6: 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13063510

APA StyleValenzuela-Fuenzalida, J. J., Martínez-Hernández, D., Pérez-Jiménez, D., Baeza, P. N., Becerra-Farfan, Á., Orellana-Donoso, M., Mejias, A. B., Syed, Q. H., Luengo, M. R., & Iwanaga, J. (2023). Prevalence and Clinical Consideration of Anatomical Variants of the Splenic Artery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Applied Sciences, 13(6), 3510. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13063510