Study on Cyber Common Operational Picture Framework for Cyber Situational Awareness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Definition of Cyberspace Operations and Cyber Awareness

2.1.1. Definition of Cyberspace Operations

- Physical Layers: Layers containing geographic components and physical network components (routers, servers, computers, etc.).

- Logical Layer: A layer that includes logical network components (Application (APP), Operational System (OS), etc.) consisting of logical connections that exist between network nodes.

- Persona Layer: A layer containing information (name, age, e-mail, social media account, etc.) about actors or users who plan and execute tasks within cyberspace.

2.1.2. Definition of Cyber Awareness

- You should be aware of the current situation: you must be able to identify and recognize attacks, which goes beyond intrusion detection.

- Pay attention to the impact of an attack: impact assessments should be performed now and in the future.

- Be aware of how things are going: situation tracking is a key component of this aspect.

- Pay attention to the behavior of the threat actor: focus on the actions of the attacker or threat actor in the situation rather than the situation itself.

- Recognize why and how the current situation occurred: causal analysis and forensics are included.

- Recognize the quality of the collected context-aware information items and derived knowledge decisions: this can be seen as part of a concrete perception.

- Evaluate the plausible future of the present situation: predict the paths and actions a threat may take in the future.

2.2. Cyber Common Operational Pictures

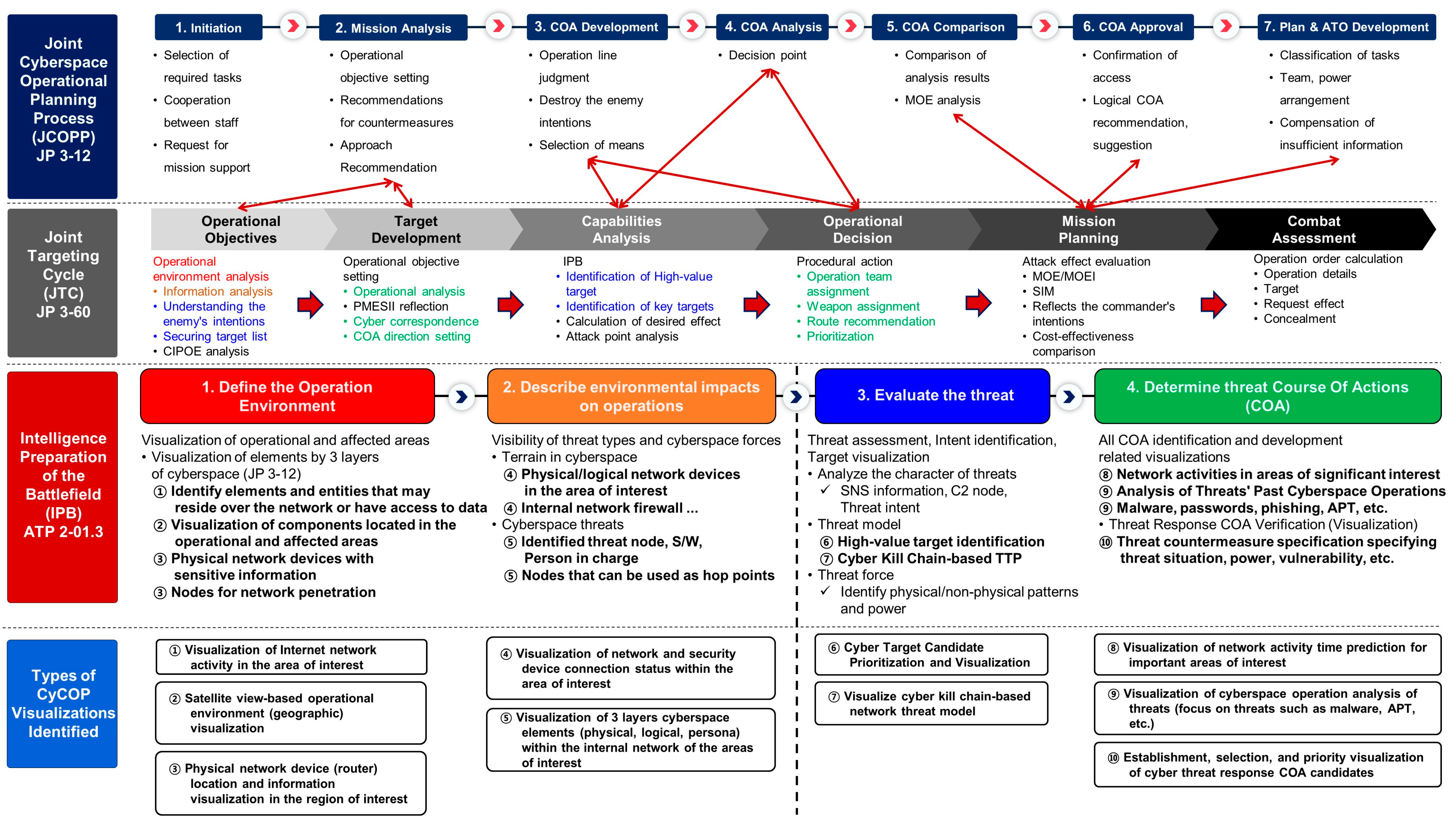

2.2.1. Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield

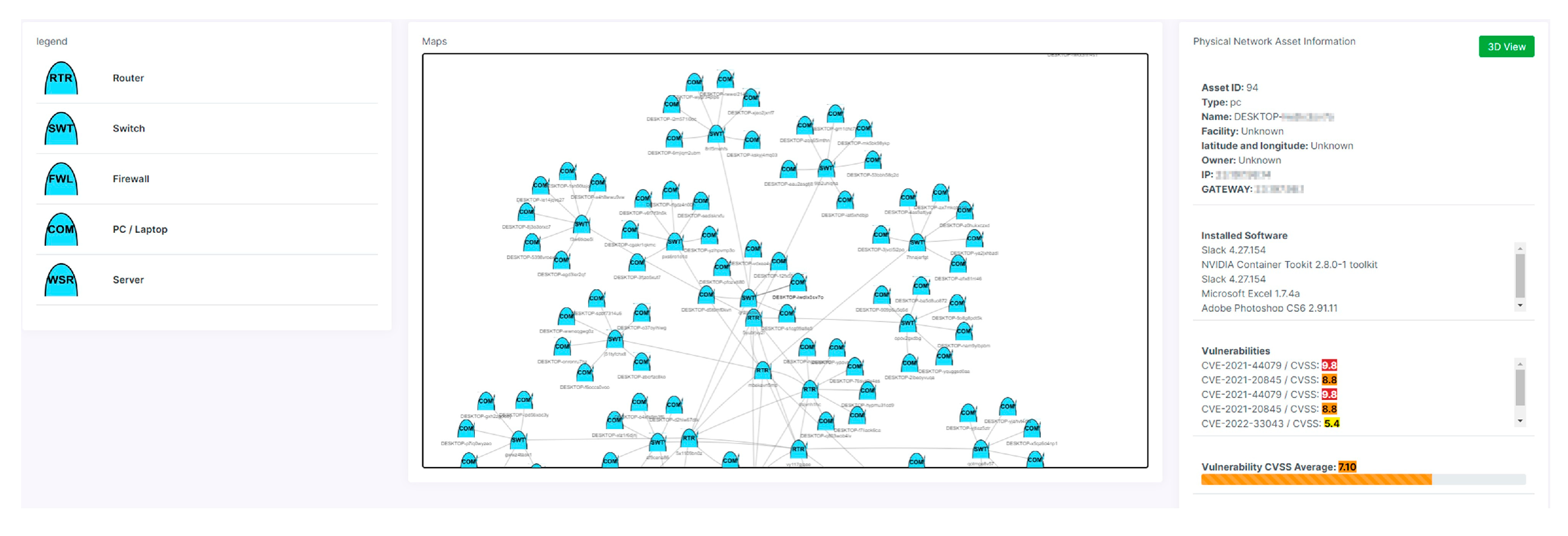

- Define the Operation Environment: it graphically visualizes the current physical locations of items and threats for each layer of cyberspace within the operational area. Table 1 lists the identification items for each layer in cyberspace.

- Describe environmental impacts on operations: the Modified Combined Obstacle Overlay reflects and visualizes the three layers of cyberspace. It is divided into an external network that can use the Internet and an internal network that does not use the Internet (internal network). It is visualized considering the contact point (firewall) connecting the external and internal networks.

- Evaluate the threat: it should update the threat characteristics, create a threat model, develop a comprehensive threat response plan, and identify high-value targets. In addition, when analyzing the cyber-attack structure and the attacker’s past patterns, it should clarify the threat situation. It should be able to see the threat’s preferred internal movement attack technique and all the malware used by the threat, and then identify assets (high-value targets) that are critical to the threat’s ability to conduct an operation or point.

- Determine threat Course of Actions: when selecting a threat response plan, the expected action (path) should be graphically displayed. In addition, the Modified Combined Obstacle Overlay should be nested to represent a threat that incorporates environmental impacts and implements specific countermeasures.

2.2.2. Identify Types of CyCOP Visualization

2.3. Cyber Common Operational Pictures Interface

2.3.1. Research on Response Time

- 1.

- Definition of Simple Response Time

- The input response displayed according to the operation of the input device reacts within approximately 0.5 s.

- -

- Character display after keyboard input, cursor movement, mouse selection, switch/button press display, scroll wheel, optical wheel, mouse click, page scan, XY entry, pointing, sketching, local update, error feedback, etc.

- Reaction within 1 s when executing a file with some capacity after operating the input device.

- -

- Turning pages, simple and frequently used actions, etc.

- Simple and repetitive function execution has a response time of 2 s.

- -

- Simple inquiry from local host, simple function execution, host update, etc.

- 2.

- Definition of Complex Response Time

- Execution that is simple but requires computation and data call outside the unit area.

- -

- General execution, the initial response to system access, input verification, input error notification, etc.

- -

- Calling various data such as threat information or map components.

- Complex execution such as complex operations and data processing.

- -

- When it involves complex sequence/function execution or program loading such as system startup or shutdown.

- -

- Remote server data call file update, complex inquiry, etc.

2.3.2. Research on CyCOP Visualization Screen UI

- Scenario Controls: a widget that allowed the user to start/pause/speed up a scenario.

- Active Persona Widget: this made it possible to set the currently active persona, which was a fictitious individual using the CyCOP scenario within the current scenario.

- Layers Widget: the user could control the layers displayed on the screen.

- Ticket Widget: display a sticker for the active persona: a “Ticket” was an action or information assigned to the current user. The Ticket Widget allowed the active persona to see all the Tickets currently assigned to it.

2.3.3. Research on Object Symbols Expressed on the Screen

2.3.4. Research on the Size of Expression Objects on the Screen

3. Design and Implementation of the CyCOP Framework

3.1. Collecting External/Internal Network Information

3.2. CyCOP Visualization

4. CyCOP System Response Speed Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CyCOP | Cyber Common Operational Picture |

| APP | Application |

| OS | Operational System |

| JOPP | Joint Operational Planning Process |

| JP | Joint Publication |

| JCOPP | Cyberspace Operational Planning Process |

| JTC | Joint Targeting Cycle |

| COP | Common Operational Picture |

| C2 | Command and Control |

| ATP | Army Techniques Publication |

| UI | User Interface |

| OSINT | Open-Source Intelligence |

| BGP | Border Gateway Protocol |

| Geo | Geographic |

| AS | Autonomous Systems |

| S/W | Software |

| H/W | Hardware |

| CVSS | Common Vulnerability Scoring System |

References

- Adlakha, R.; Sharma, S.; Rawat, A.; Sharma, K. Cyber Security Goal’s, Issue’s, Categorization & Data Breaches. In Proceedings of the 2019 international conference on machine learning, big data, cloud and parallel computing (COMITCon), Faridabad, India, 14–16 February 2019; pp. 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Cabaj, K.; Kotulski, Z.; Księżopolski, B.; Mazurczyk, W. Cybersecurity: Trends, issues, and challenges. EURASIP J. Inf. Secur. 2018, 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, D. Quadrennial Defense Review Report; Department of Defense: Virginia, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K.D. Joint Publication (JP) 3-12 Cyberspace Operation; The Joint Staff: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zaporozhets, O.; Syvak, O. In the Line of Russian Aggression: Ukraine, hybrid warfare, and cybersecurity defense. In Routledge Companion to Global Cyber-Security Strategy; Routledge: Oxfordshire, Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Husák, M.; Laštovička, M.; Plesník, T. Handling Internet Activism during the Russian Invasion of Ukraine: A Campus Network Perspective. Digit. Threat. Res. Pract. 2022, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyber Attack Trends in the Midst of Warfare—The Numbers behind the First Days of the Conflict. Available online: https://blog.checkpoint.com/2022/02/27/196-increase-in-cyber-attacks-on-ukraines-government-and-military-sector/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Patrick, D.G. NIST Special Publication 800-30 Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments; National Institute of Standards and Technology U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hersey, N.S. FM 3-12 Cyberspace and Electromagnetic Warfare; Department of the Army: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ducheine, P.; Van Haaster, J. Fighting power, targeting and cyber operations. In Proceedings of the 2014 6th International Conference on Cyber Conflict (CyCon 2014), Tallinn, Estonia, 3–6 June 2014; pp. 303–327. [Google Scholar]

- Poteete, P.W. Implementing the DoD Joint Operation Planning Process for Private Industry Enterprise Security; Naval Postgraduate School Monterey Ca Dept of Information Sciences: Monterey, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Scaparrotti, C.M. Joint Publication 3-60 Joint Targeting; Joint Chiefs of Staff: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, A.; Aved, A.; Blasch, E. Situational Awareness: Techniques, Challenges, and Prospects. AI 2022, 3, 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. In Situational Awareness; Routledge: Oxfordshire, Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Endsley, M.R. Design and evaluation for situation awareness enhancement. In Proceedings of the Human Factors Society Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 1 October 1988; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Barford, P.; Dacier, M.; Dietterich, T.G.; Fredrikson, M.; Giffin, J.; Jajodia, S.; Jha, S.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Ning, P. Cyber SA: Situational awareness for cyber defense. In Cyber Situational Awareness; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, U.; Brynielsson, J. Cyber situational awareness—A systematic review of the literature. Comput. Secur. 2014, 46, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacq, O.; Brosset, D.; Kermarrec, Y.; Simonin, J. Cyber attacks real time detection: Towards a cyber situational awareness for naval systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Cyber Situational Awareness, Data Analytics and Assessment (Cyber SA), Oxford, UK, 3–4 June 2019; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Mittu, R.; Segaria, F. Common Operational Picture (cop) and Common Tactical Picture (ctp) Management via a Consistent Networked Information Stream (cnis); Naval Research Lab.: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Keuhlen, D.T.; Bryant, O.L.; Young, K.K. The Common Operational Picture in Joint Vision 2020: A Less Layered Cake; National Defense Univ Norfolk va Joint and Combined Warfighting School: Norfolk, Virginia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baar, D.D.; Shoemaker, G. Pliable Display Technology for the Common Operational Picture; IDELIX Software Inc.: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, J. Emergency Response: Unity of Effort through a Common Operational Picture; Army War College: Carlisle, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wreski, E.E.; Lavoie, E.A. A Concept of Operations for an Unclassified Common Operational Picture in Support of Maritime Domain Awareness; Naval Postgraduate School: Monterey, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve, M.; Pérez, I.; Palau, C.; Carvajal, F.; Hingant, J.; Fresneda, M.A.; Sierra, J.P. Cyber Common Operational Picture: A Tool for Cyber Hybrid Situational Awareness Improvement; Technical Report STO-MP-IST-148; North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Science and Technology Organization (STO): Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pahi, T.; Leitner, M.; Skopik, F. Preparation, modelling, and visualisation of cyber common operating pictures for national cyber security centres. J. Inf. Warf. 2017, 16, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Noel, S.; Purdy, S.; O’Rourke, A.; Overly, E.; Chen, B.; DiFonzo, C.; Chen, J.; Sakellis, G.; Hegde, M.; Sapra, M. Graph analytics and visualization for cyber situational understanding. J. Def. Model. Simul. 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutzwiller, R.S.; Hunt, S.M.; Lange, D.S. A task analysis toward characterizing cyber-cognitive situation awareness (CCSA) in cyber defense analysts. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Multi-Disciplinary Conference on Cognitive Methods in Situation Awareness and Decision Support (CogSIMA), San Diego, CA, USA, 21–25 March 2016; pp. 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jajodia, S.; Noel, S.; Kalapa, P.; Albanese, M.; Williams, J. Cauldron mission-centric cyber situational awareness with defense in depth. In Proceedings of the 2011-MILCOM 2011 Military Communications Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 7–10 November 2011; pp. 1339–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, M.; Catto, M.G.; Bird, M. Increased Space Situational Awareness through Augmented Reality Enhanced Common Operating Pictures. In Proceedings of the Advanced Maui Optical and Space Surveillance Technologies Conference, Maui, HI, USA, 1–14 September 2018; pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Llopis, S.; Hingant, J.; Pérez, I.; Esteve, M.; Carvajal, F.; Mees, W.; Debatty, T. A comparative analysis of visualisation techniques to achieve cyber situational awareness in the military. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Military Communications and Information Systems (ICMCIS), Warsaw, Poland, 22–23 May 2018; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Jayatilaka, A.; Nasim, M.; Grobler, M.; Zahedi, M.; Babar, M.A. Systematic Literature Review on Cyber Situational Awareness Visualizations. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 57525–57554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucette, H. Identifying Requirements for a Cyber Common Operating Picture (CyCOP): Information Collection; Defence Research and Development Canada: Ottawa, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dillabaugh, C.; Bennett, D. CyberCOP: Cyber Situational Awareness Demonstration Tool; Defence Research and Development Canada: Ottawa, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, L.; Grégoire, M.; Lagadec, P.; Lefebvre, J.; Luiijf, E.; Tolle, J. Coalition Network Defence Common Operational Picture; Fraunhofer Society Wachtberg (Germany) Fraunhofer Inst for Communication Information Processing and Ergonomics: Bonn, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Headquarters, Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 2-01.3, Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield; Department of the Army: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Department of Defense, United States of America, Military-Standard (MIL-STD)-1472H, DESIGN CRITERIA STANDARD, HUMAN ENGINEERING; Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Kim, H.; Song, H.; Park, S. Proper response times and design factors influencing user satisfaction with diverse touch tap operations for the smartphone. Arch. Des. Res. 2014, 27, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B. Response time and display rate in human performance with computers. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 1984, 16, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCroskey, E.D.; Mock, C.A. Operational graphics for cyberspace. Jt. Force Q. (JFQ) 2017, 85, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense, United States of America, Military-Standard (MIL-STD)-2525D, Interface Standard, Joint Military Symbology; Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- University of Oregon Route Views Archive Project. Available online: http://archive.routeviews.org/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Butler, H.; Daly, M.; Doyle, A.; Gillies, S.; Hagen, S.; Schaub, T. The Geojson Format. Available online: http://www.hjp.at/doc/rfc/rfc7946.html (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Maxmind. Available online: https://www.maxmind.com/en/home (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Caida. Available online: https://www.caida.org/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- SecurityTrails. Available online: https://securitytrails.com/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- ip-api. Available online: https://ip-api.com/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- WhoisXMLAPI. Available online: https://www.whoisxmlapi.com/ (accessed on 16 January 2023).

- Scarfone, K.; Mell, P. An analysis of CVSS version 2 vulnerability scoring. In Proceedings of the 2009 3rd International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 15–16 October 2009; pp. 516–525. [Google Scholar]

| Cyberspace Layer | Identification Item |

|---|---|

| Physical Network Layer | Cyber C2 system, cyber network bridgehead node, network device (PC, server, router, etc.), Internal/External network contact node, IDS/IPS, etc. |

| Logical Network Layer | Website, vulnerability, resource URL path, messenger, repository address, S/W (Software), OS, One Time Password APP, etc. |

| Persona Network Layer | Advanced Persistent Threats (APT) groups, documents, photos, videos, private keys, public keys, passwords, etc. |

| Study | Implemented Visualization Number |

|---|---|

| Esteve et al. [24] | ② |

| Pahi et al. [25] | Only visualization concept/methodology is presented |

| Noel et al. [26] | ②, ④ |

| Gutzwiller et al. [27] | Only visualization concept/methodology is presented |

| Jajodia et al. [28] | ④ |

| Jenkins et al. [29] | ②, ④ |

| Llopis et al. [30] | ②, ③, ④ |

| Jiang et al. [31] | There are only reviews of several visualization studies |

| Doucette [32] | Only visualization concept/methodology is presented |

| Dillabaugh et al. [33] | ②, ④ |

| Beaudoin et al. [34] | Only visualization concept/methodology is presented |

| System Interpretation | Response Time Definition | Time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| Key response, including scroll wheels, optical wheels, mouse clicks | Key pressed until positive response (e.g., “click”) | 0.1 |

| Key print | Key pressed until the appearance of the character | 0.2 |

| Page turn | End of the request until the first few lines are visible | 1.0 |

| Page scan | End of the request until text begins to scroll | 0.5 |

| XY entry | From the selection of field until visual verification | 0.2 |

| Pointing | From the input of point to display point | 0.2 |

| Sketching | From the input of point to display of line | 0.2 |

| Local update | Change to image using the local database (e.g., new menu list from display buffer) | 0.5 |

| Host update | Change where data is at the host in a readily accessible form (e.g., a scale change of existing image) | 2.0 |

| File update | Image update requires access to a host file | 10 |

| Inquiry (simple) | From command until the display of a commonly used message | 2.0 |

| Inquiry (complex) | Response message requires seldom used calculations in graphic form | 10 |

| Error feedback | From the entry of input until an error message appears | 0.2 |

| Type of Task | Appropriate Response Time (s) |

|---|---|

| Switch/button pressed indication | 0.1 |

| Display text after typing on the keyboard | 0.1–0.2 |

| Display touched text | 0.2 |

| Initial response to system access | 1–3 |

| Function execution | |

| Simple function | 2 |

| Complex function | 5 |

| When loading occurs during function execution | 15–60 |

| Input confirmation, input error notification | 2–4 |

| Type of Task | Appropriate Response Time (s) |

|---|---|

| Typing, moving the cursor, clicking the mouse | 0.05–0.15 |

| Simple and frequently used function | 1 |

| Common function | 2–4 |

| Complex function | 8–12 |

| Input confirmation, input error notification | 2–4 |

| Simple/Complex Response Time | Behavior | MIL-STD-1472H [37] | Kim et al. [38] | Shneiderman [39] | Common |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Response Time | Key response, including scroll wheels, optical wheels, mouse clicks | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.05–0.15 | 0.1 |

| Key print | 0.2 | 0.1–0.2 | 0.05–0.15 | 0.2 | |

| XY entry, Pointing | 0.2 | ||||

| Sketching | 0.2 | 2–4 | |||

| Error feedback | 0.2 | 2 | |||

| Page scan | 0.5 | ||||

| Local update | 0.5 | ||||

| Page move | 1.0 | ||||

| Host update | 2.0 | ||||

| Inquiry (simple) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2–4 | 2.0 | |

| Complex Response Time | Inquiry (complex) | 10 | 5.0 | 8–12 | 10 |

| File update | 10 |

| Description | Icon |

|---|---|

| ROUTER Type: Entity Type Entity: DEVICE TYPE Symbol Set Code: 60 Code: 140200 |  |

| FIREWALL Type: Entity Type Entity: DEVICE TYPE Symbol Set Code: 60 Code: 140900 |  |

| … | … |

| Factor | Optimum | Preferred Limits | Acceptable Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio of viewing distance to screen diagonal | 4.0 | 3.0 to 6.0 | 2.0 to 10 |

| Angle off centerline | 0° | 0 to 20° | 0 to 30° |

| Image luminance (no film in the operating projector) | 35 cd/m2 1/ | 27 to 48 cd/m2 1/ | 17 to 70 cd/m2 1/ |

| Luminance variation across the screen (ratio of maximum to minimum luminance) | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.0 |

| Luminance variation as a function of viewing location (ratio of maximum to minimum luminance) | 1.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 |

| The ratio of ambient light to the brightest part of the image | 0 | 0.002 to 0.01 | 0.1 maximum 2/ |

| 5.17.18.6 Symbol size and image quality for complex shapes. The size of a symbol or graphic shall be such that all text or graphics embedded within the symbol (e.g., label within symbol) shall subtend not less than 2.9 milliradians (10 min) of visual angle from the greatest anticipated viewing distance. | |||

| Items | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| OS | Windows 10 Pro |

| Processor | AMD Ryzen 7 3700X 8-Core Processor 3.59 GHz |

| Memory | 64 GB |

| Development languages, software and tools | Python 3.9, django 4.1, deck.gl 8.4, Unity 2022.1.13., bootstrap 5.2.0, oracle 21c, Google Maps Platform |

| Behavior | ① | ② | ③ | ④ | ⑤ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inquiry (simple) | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.14 |

| Inquiry (complex) | 1.50 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, K.; Youn, J.; Yoon, S.; Kang, J.; Kim, K.; Shin, D. Study on Cyber Common Operational Picture Framework for Cyber Situational Awareness. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2331. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042331

Kim K, Youn J, Yoon S, Kang J, Kim K, Shin D. Study on Cyber Common Operational Picture Framework for Cyber Situational Awareness. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(4):2331. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042331

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Kookjin, Jaepil Youn, Sukjoon Yoon, Jiwon Kang, Kyungshin Kim, and Dongkyoo Shin. 2023. "Study on Cyber Common Operational Picture Framework for Cyber Situational Awareness" Applied Sciences 13, no. 4: 2331. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042331

APA StyleKim, K., Youn, J., Yoon, S., Kang, J., Kim, K., & Shin, D. (2023). Study on Cyber Common Operational Picture Framework for Cyber Situational Awareness. Applied Sciences, 13(4), 2331. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042331