Building a Design-Rationale-Centric Knowledge Network to Realize the Internalization of Explicit Knowledge

Abstract

1. Introduction

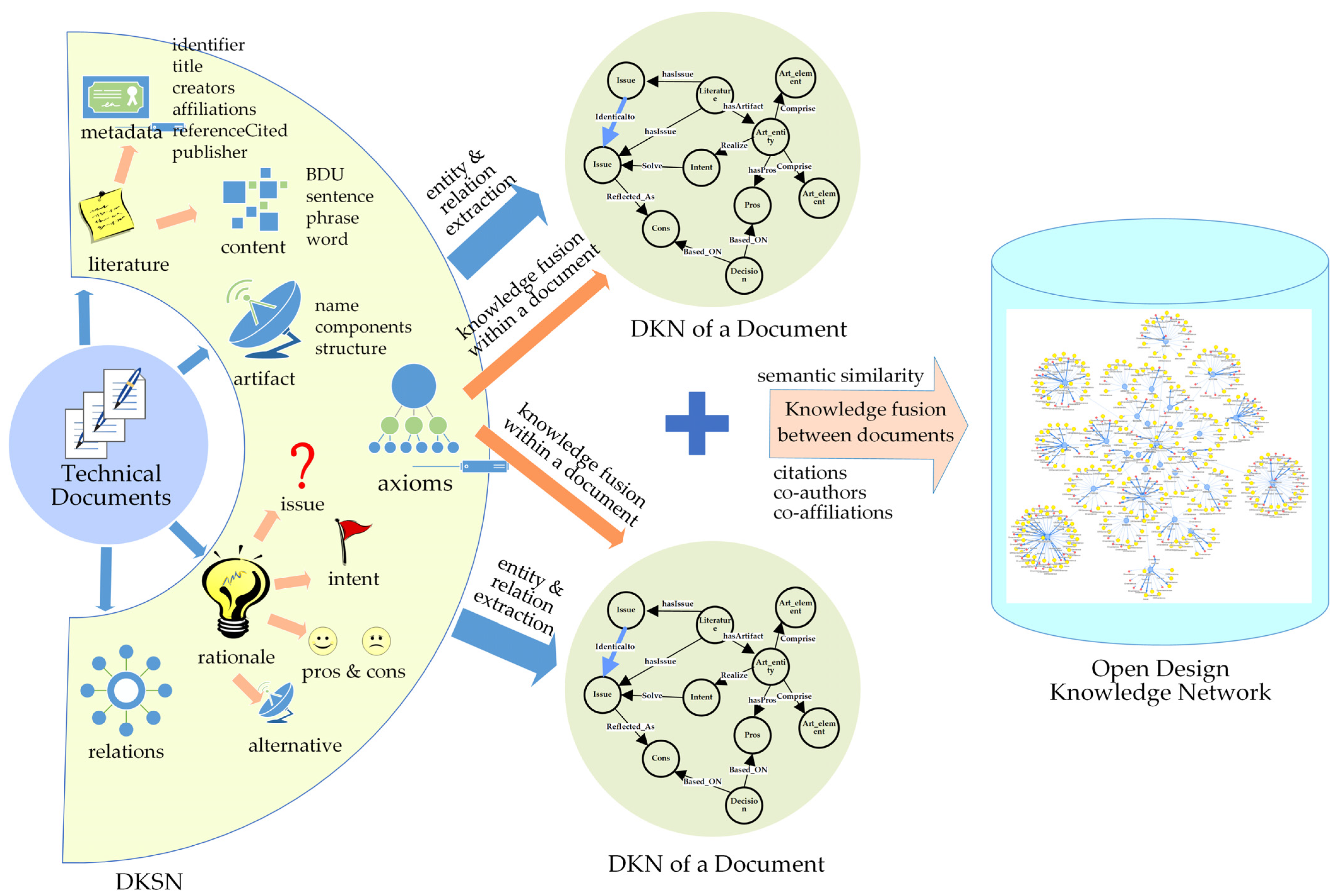

- The DKSN, a knowledge network metamodel based on DR theory, is proposed to provide designers with innovative ideas, inspirations, and creative stimuli.

- The DKSN takes into consideration the requirements of text mining, making it a convenient, rapid, and efficient approach for the capture, sharing, and dissemination of design knowledge in documents.

- It can be used to integrate DR from patents, scholarly articles, and other publicly available documents to build an ODKN.

2. Related Work

2.1. Design Rationale Representations

2.2. Design Knowledge Network

2.3. Semantic Network and Knowledge Fusion

3. Proposed Method

3.1. Framework of the Proposed Method

3.2. Design Knowledge Network

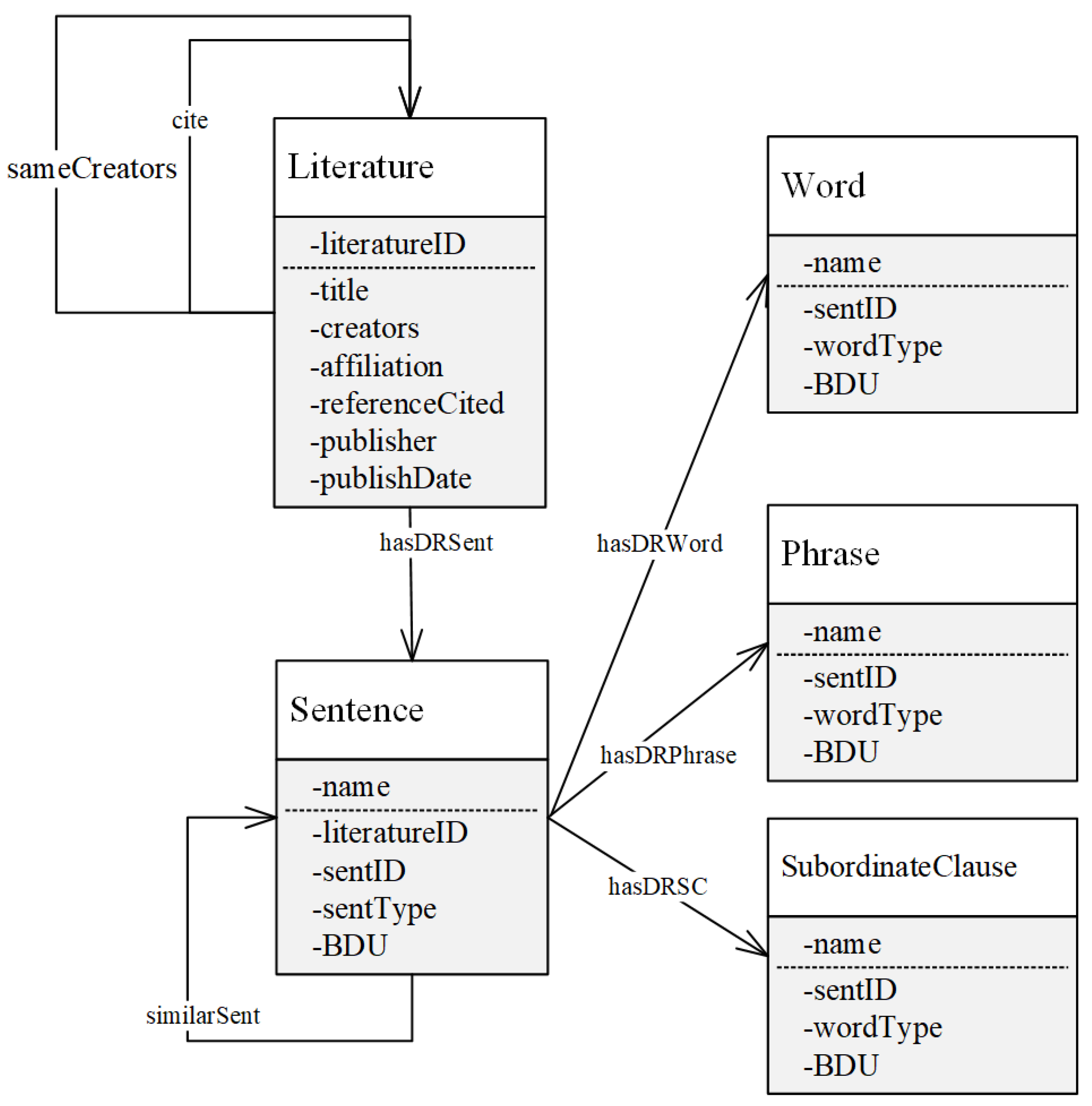

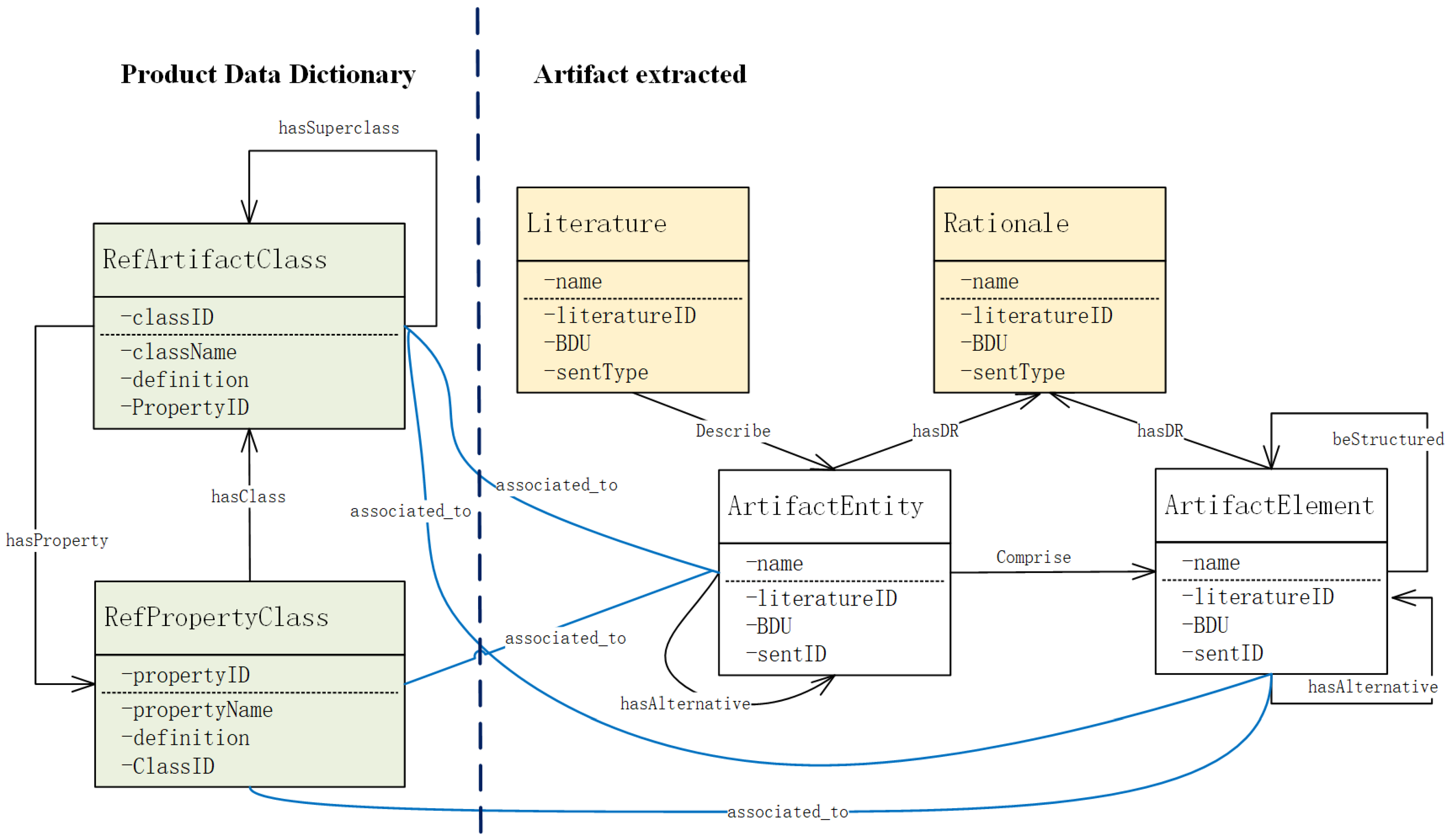

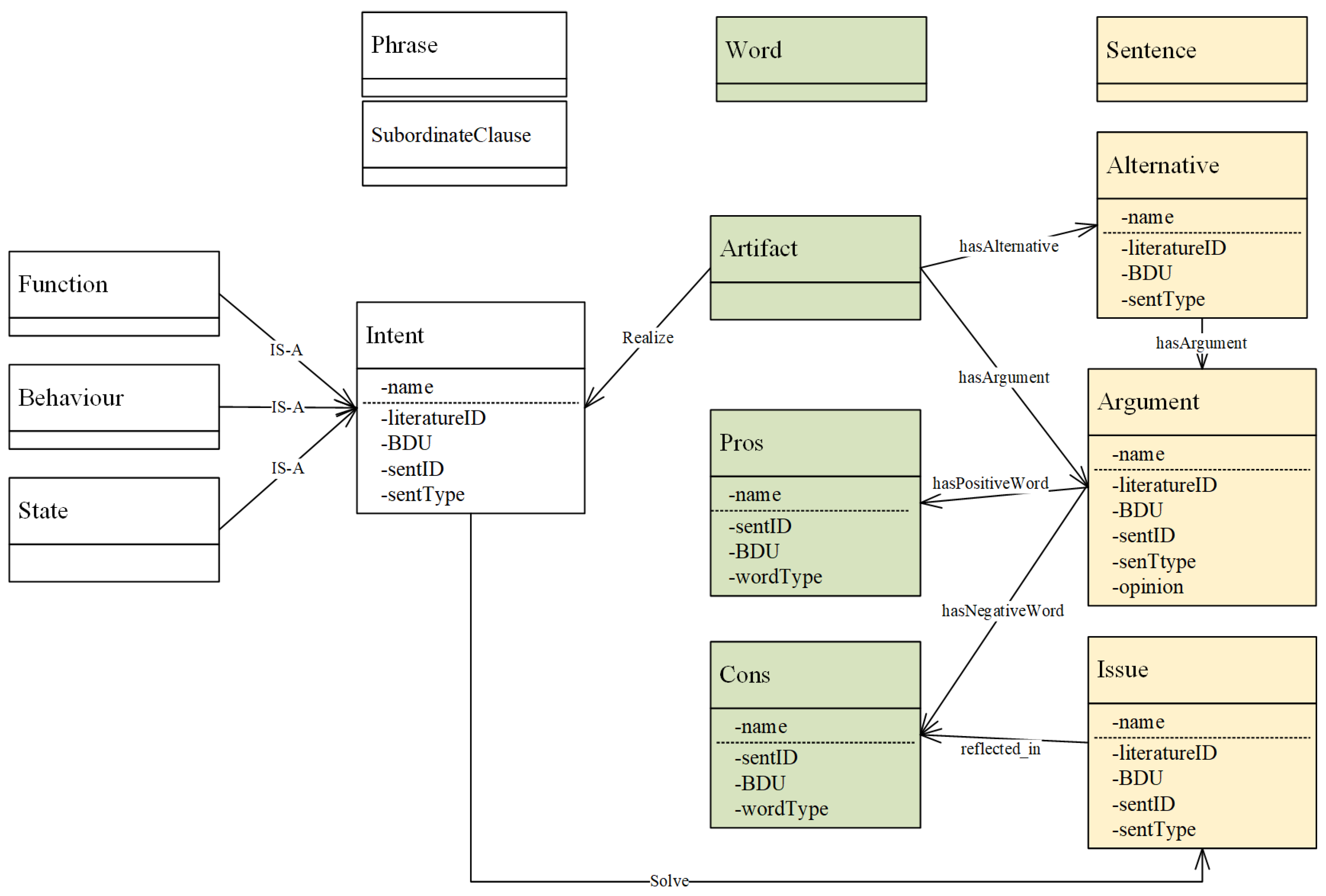

3.3. Design Knowledge Semantic Network

3.3.1. Overview

- Classes or Nodes (N). In this paper, entities, nodes, or classes are considered synonyms, which are expressed as “(class)”.

- Properties (P). Related information about a class. For example, names, identifiers, authors, and other relevant information can be the property of a document; materials, geometric dimensions, and functional descriptions can be the properties of an artifact.

- Edges (E) or Relations. Edges represent the logical relationships between nodes or classes. They include generic relationships as defined in OWL or protégé tools, such as IS-A; some specific DR relationships within the DKSN network, such as Realize, Describe, hasIntent, and hasOpionion relations, are expressed in the form of directed arrows: -[relation]->.

- Axiom rules (A). Axiom Rules are expressed with the Semantic Web Rule Language (SWRL). SWRL is an expressive OWL-based rule language. SWRL allows for the definition of DKSN-specific rules that can be expressed in OWL concepts to provide more powerful deductive reasoning capabilities.

3.3.2. Literature Ontology

3.3.3. Artifact Ontology

3.3.4. Rationale Ontology

- Issue—problems with existing artifacts or requirements for new artifacts. The detailed description of the issue is usually embodied in the description of the shortcomings of existing artifacts, which are generally expressed using negative statements. Issues are the core and focus of the entire design document that need to be addressed.

- Intent—goals and expectations that the designer wants to achieve with the artifact. Design intent can include the function of the design object, such as the drone realizing the functions of transportation, maintenance, photography, and others. It can also include the performance intent of an artifact, such as safety, economy, reliability, and others; the artifact implements a specific behavior or operational intent, such as vertical take-off and landing operations of a drone. Hence, design intent addresses a design problem or set of problems.

- Argument—advantages and disadvantages of the artifact, positions for or against, opinion analysis from the designer or interested parties. It can include a. cons, the descriptions of the deficiencies, shortcomings, and negatives of alternatives or other traditional artifacts; and b. pros, used to express positive information such as excellent functions, reliable performance, and a wide range of applications.

- Alternative—other artifacts, design options, or relevant solutions.

- Relationships in rationale knowledge networks and other relevant relations include:

3.3.5. Axioms

3.4. Knowledge Fusion

4. Empirical Study

4.1. Data Preparation

4.2. Entities and Relations Extraction

4.3. Knowledge Fusion

4.3.1. Knowledge Fusion within a Document

4.3.2. Knowledge Fusion between Documents

4.4. Comparison and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BS 7000-1:2008; Design Management Systems—Part 1: Guide to Managing Innovation. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2008.

- Kodama, M. Boundaries Knowledge (Knowing)—A Source of Business Innovation. Knowl. Process Manag. 2019, 26, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rob, B.; Ken, W.; Michael, M.; David, K. Capturing Design Rationale. Comput.-Aided Des. 2009, 41, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Setchi, R.; Bouchard, C. In Search of Design Inspiration: A Semantic-Based Approach. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Cavallucci, D. A New Function-Based Patent Knowledge Retrieval Tool for Conceptual Design of Innovative Products. Comput. Ind. 2020, 115, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, U.Y.; Nadeau, J.-P.; Scaravetti, D. A New Method for Extracting Knowledge from Patents to Inspire Designers during the Problem-Solving Phase. J. Eng. Des. 2017, 28, 369–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goucher-Lambert, K.; Gyory, J.T.; Kotovsky, K.; Cagan, J. Adaptive Inspirational Design Stimuli: Using Design Output to Computationally Search for Stimuli That Impact Concept Generation. J. Mech. Des. 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Srinivasan, V.; Luo, J. Patent Stimuli Search and Its Influence on Ideation Outcomes. Des. Sci. 2017, 3, e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Stacey, M. Sources of Inspiration: A Language of Design. Des. Stud. 2000, 21, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybvik, H.; Abelson, F.G.; Aalto, P.; Goucher-Lambert, K.; Steinert, M. Inspirational Stimuli Improve Idea Fluency during Ideation: A Replication and Extension Study with Eye-Tracking. Proc. Des. Soc. 2022, 2, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, G.J.; Lee, J.H.; Suh, H.W. Semantic Relation Based Personalized Ranking Approach for Engineering Document Retrieval. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2015, 29, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Huang, K. A Hypernetwork-Based Approach to Collaborative Retrieval and Reasoning of Engineering Design Knowledge. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2019, 42, 100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.G.; Daniel, R. Design Knowledge and Design Rationale: A Framework for Representation, Capture, and Use; Knowledge Systems Laboratory, Computer Science Department, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dworschak, F.; Kügler, P.; Schleich, B.; Wartzack, S. Model and Knowledge Representation for the Reuse of Design Process Knowledge Supporting Design Automation in Mass Customization. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, G.; Liu, J.; Hou, Y. Design Rationale Knowledge Management: A Survey; Luo, Y., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, G.; Shipman, F. Collaborative Design Rationale and Social Creativity in Cultures of Participation. In Creativity and Rationale: Enhancing Human Experience by Design; Carroll, J.M., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2013; pp. 423–447. ISBN 978-1-4471-4111-2. [Google Scholar]

- Morteza, P.; Joel, J.; Fredrik, E. Capturing, Structuring and Accessing Design Rationale in Integrated Product Design and Manufacturing Processes. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2016, 30, 522–536. [Google Scholar]

- Mandorli, F.; Borgo, S.; Wiejak, P. From Form Features to Semantic Features in Existing MCAD: An Ontological Approach. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 44, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopsill, J.A.; McAlpine, H.C.; Hicks, B.J. A Social Media Framework to Support Engineering Design Communication. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2013, 27, 580–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhang, Y.; Saad, M. An Approach to Capturing and Reusing Tacit Design Knowledge Using Relational Learning for Knowledge Graphs. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.W.S.; James, M.R.; Theodore, L.; Zoe, K. Automated Generation of Engineering Rationale, Knowledge and Intent Representations during the Product Life Cycle. Virtual Real. 2012, 16, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hiroyuki, Y. Systematization of Design Knowledge. CIRP Ann. 1993, 42, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bijl-Brouwer, M.V.D.; Malcolm, B. Systemic Design Principles in Social Innovation: A Study of Expert Practices and Design Rationales. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2020, 6, 386–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, E.J.; Yakemovic, K.B. A Process-Oriented Approach to Design Rationale. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 1991, 6, 357–391. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, M.S.I.; Catherine, C.M. Formality Considered Harmful: Experiences, Emerging Themes, and Directions on the Use of Formal Representations in Interactive Systems. Comput. Support. Coop. Work 1999, 8, 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Decision Representation Language (DRL) and Its Support Environment; MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory Working Papers, WP-325; MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jeff, C.; Michael, L.B. GIBIS: A Hypertext Tool for Exploratory Policy Discussion. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 1988, 6, 303–331. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Johnson, A.L.; Bracewell, R.H. The Retrieval of Structured Design Rationale for the Re-Use of Design Knowledge with an Integrated Representation. Adv. Eng. Inform. Based Eng. Support Complex Prod. Des. 2012, 26, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Zhao, L.; Milisavljevic-Syed, J.; Ming, Z. Integrating and Navigating Engineering Design Decision-Related Knowledge Using Decision Knowledge Graph. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 50, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, G.; Wanner, L. Towards the Derivation of Verbal Content Relations from Patent Claims Using Deep Syntactic Structures. Knowl. -Based Syst. 2011, 24, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, B.; Qiao, Y.; Gung, J.; Mathur, T.; Burge, J.E. Using Text Mining Techniques to Extract Rationale from Existing Documentation; Gero, J.S., Hanna, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 457–474. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, M.; Guerrero, M.; Burge, J. Using Evolutionary Algorithms to Select Text Features for Mining Design Rationale. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2020, 34, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtanović, Z.; Maalej, W. On User Rationale in Software Engineering. Requir. Eng. 2018, 23, 357–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Kwong, C.K.; Lee, W.B. A New Design Rationale Representation Model for Rationale Mining. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Buis, J.J. A Semantic Representation Model for Design Rationale of Products. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2013, 27, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horst, W.J.R.; Melvin, M.W. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, W.; Rittel, H.W.J. Issues as Elements of Information Systems; Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California: Oakland, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, M.; Richard, Y.; Victoria, B.; Thomas, M. Questions, Options, and Criteria: Elements of Design Space Analysis. Hum. -Comput. Interact. 1991, 6, 201–250. [Google Scholar]

- de Medeiros, A.P.; Schwabe, D. Kuaba Approach: Integrating Formal Semantics and Design Rationale Representation to Support Design Reuse. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2008, 22, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetsuo, T. From General Design Theory to Knowledge-Intensive Engineering. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 1994, 8, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Hu, X. A Reuse Oriented Representation Model for Capturing and Formalizing the Evolving Design Rationale. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2013, 27, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Ma, Y. A Functional Feature Modeling Method. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; He, F.; Lv, X.; Cai, W. On the Role of Generating Textual Description for Design Intent Communication in Feature-Based 3D Collaborative Design. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2019, 39, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lai, K.-Y. What’s in Design Rationale? Hum.-Comput. Interact. 1991, 6, 251–280. [Google Scholar]

- Kenett, Y.N.; Faust, M. A Semantic Network Cartography of the Creative Mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2019, 23, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenett, Y.N.; Anaki, D.; Miriam, F. Investigating the Structure of Semantic Networks in Low and High Creative Persons. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Li, W. A Novel Function-Structure Concept Network Construction and Analysis Method for a Smart Product Design System. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, G. Knowing Knowledge; Lulu.com. 2006. ISBN 978-1-4303-0230-8. Available online: https://www.knowingknowledge.com/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Johansson, J.; Contero, M.; Company, P.; Elgh, F. Supporting Connectivism in Knowledge Based Engineering with Graph Theory, Filtering Techniques and Model Quality Assurance. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2018, 38, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarica, S.; Luo, J. Design knowledge representation with technology semantic network. Proc. Des. Soc. 2021, 1, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, G.B.; Ferreira, J.C.E.; Messerschmidt, P.H.Z. Design Structure Network (DSN): A Method to Make Explicit the Product Design Specification Process for Mass Customization. Res. Eng. Des. 2020, 31, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Luo, X. An Automatic Literature Knowledge Graph and Reasoning Network Modeling Framework Based on Ontology and Natural Language Processing. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2019, 42, 100959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Andreas, S. Analysis and Visualization of Citation Networks, Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-031-02291-3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Z.; Song, B.; Liu, L. Long-Term Knowledge Evolution Modeling for Empirical Engineering Knowledge. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2017, 34, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M.M.U.; Gul, M.J.J.; Paul, A.; Khan, A.A.; Ahmad, R.W.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C.; Bakiras, S. Multilevel Graph-Based Decision Making in Big Scholarly Data: An Approach to Identify Expert Reviewer, Finding Quality Impact Factor, Ranking Journals and Researchers. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2021, 9, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A. 2012 Introducing the Knowledge Graph: Things, Not Strings. Available online: https://www.blog.google/products/search/introducing-knowledge-graph-things-not/ (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Hogan, A.; Blomqvist, E.; Cochez, M.; Amato, C.D.; Melo, G.D.; Gutierrez, C.; Kirrane, S.; Gayo, J.E.L.; Navigli, R.; Neumaier, S.; et al. Knowledge Graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Vu, D.T.; Jung, J.J. Knowledge Graph Fusion for Smart Systems: A Survey. Inf. Fusion 2020, 61, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, B.; Bao, J. A Knowledge Graph-Based Data Representation Approach for IIoT-Enabled Cognitive Manufacturing. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Hua, B.; Gu, X.; Lu, Y.; Peng, T.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, X.; Bao, J. An End-to-End Tabular Information-Oriented Causality Event Evolutionary Knowledge Graph for Manufacturing Documents. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2021, 50, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringsquandl, M.; Lamparter, S.; Lepratti, R.; Kröger, P.; Lödding, H. Knowledge Fusion of Manufacturing Operations Data Using Representation Learning; Lödding, H., Riedel, R., Thoben, K.-D., von Cieminski, G., Kiritsis, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 302–310. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Hu, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Tang, S.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, W. MEFE: A Multi-FEature Knowledge Fusion and Evaluation Method Based on BERT. In Proceedings of the Algorithms and Architectures for Parallel Processing; Qiu, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 449–462. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Hirata, T.; Bigelow, S.J.; Hirose, A.; Kohlbacher, F. The Theoretical Framework. In Managing Flow: A Process Theory of the Knowledge-Based Firm; Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., Hirata, T., Bigelow, S.J., Hirose, A., Kohlbacher, F., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2008; pp. 18–52. ISBN 978-0-230-58370-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dubberly, H.; Evenson, S. Design as Learning—Or “Knowledge Creation”—The SECI Model. Interactions 2011, 18, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Bratianu, C.; Dabija, D.-C.; Popa, S. Capitalizing Online Knowledge Networks: From Individual Knowledge Acquisition towards Organizational Achievements. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN 0-262-19374-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Design Rationale Systems: Understanding the Issues. IEEE Expert 1997, 12, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings Using Siamese BERT-Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); Association for Computational Linguistics: Hong Kong, China, November 2019; pp. 3982–3992. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.; Li, J.; Reddi, S.J.; Hseu, J.; Kumar, S.; Bhojanapalli, S.; Song, X.; Demmel, J.; Keutzer, K.; Hsieh, C.-J. Large Batch Optimization for Deep Learning: Training BERT in 76 Minutes. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1904.00962. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Minneapolis, MN, USA, June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kwong, C.K.; Lee, W.B. Learning the “Whys”: Discovering Design Rationale Using Text Mining—An Algorithm Perspective. Comput. Aided Des. 2012, 44, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

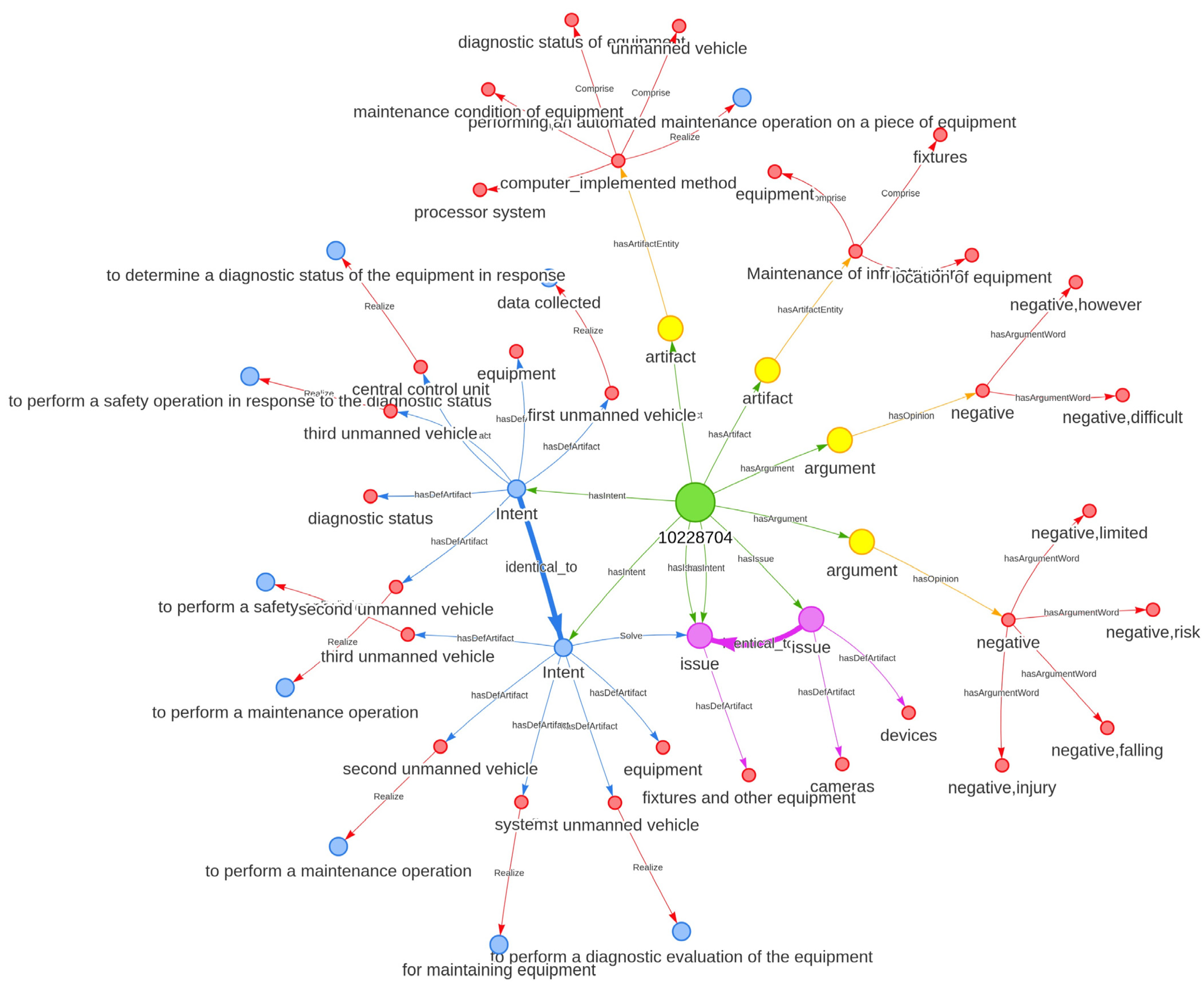

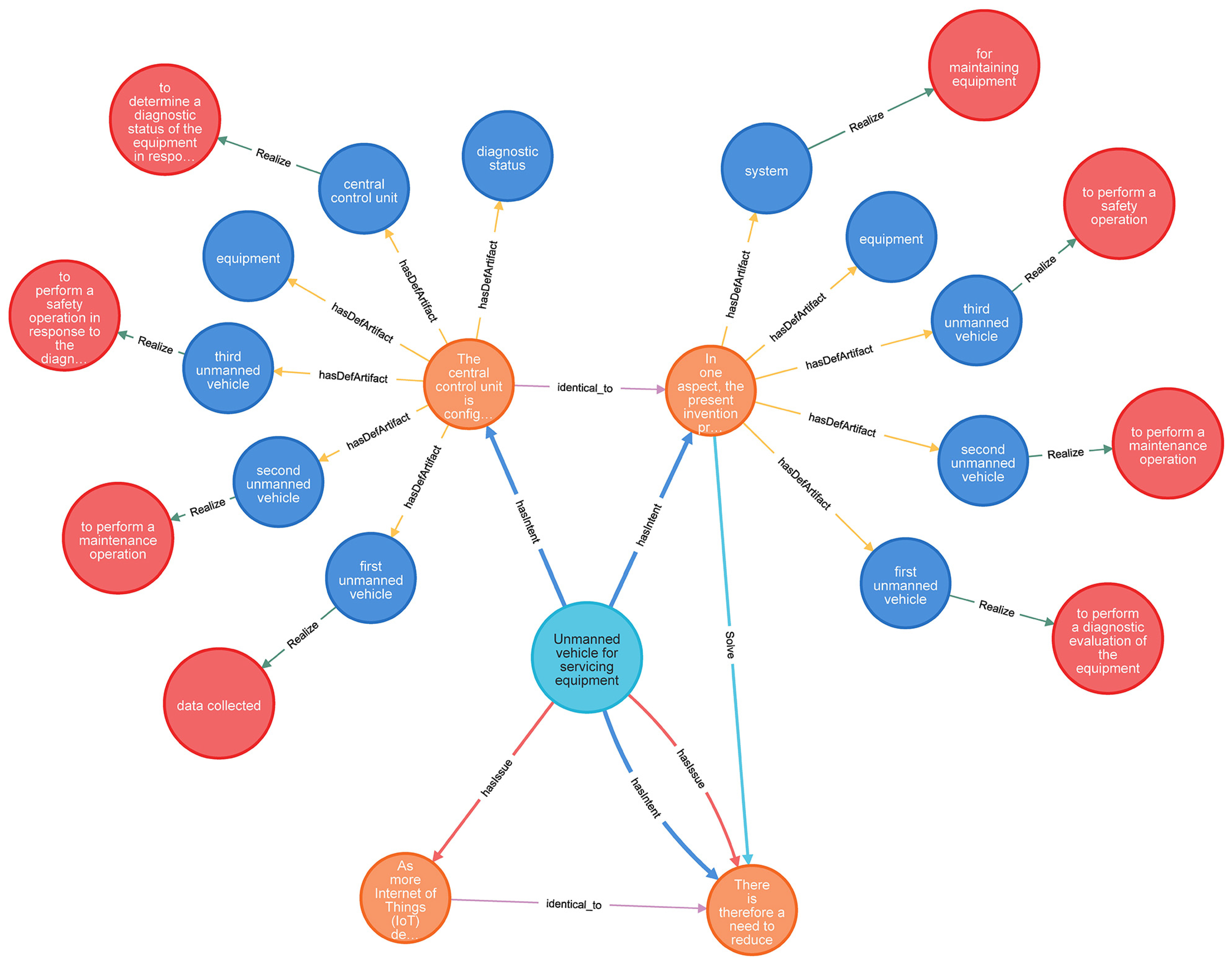

10228704) represents the patent, and 10228704 is the patent number; middle sized nodes (

10228704) represents the patent, and 10228704 is the patent number; middle sized nodes ( artifact, argument, issue, intent) are DR sentence nodes. Other small nodes are feature word nodes, such as artifact entities, artifact elements, intent, pros and cons, and others.

artifact, argument, issue, intent) are DR sentence nodes. Other small nodes are feature word nodes, such as artifact entities, artifact elements, intent, pros and cons, and others.

10228704) represents the patent, and 10228704 is the patent number; middle sized nodes (

10228704) represents the patent, and 10228704 is the patent number; middle sized nodes ( artifact, argument, issue, intent) are DR sentence nodes. Other small nodes are feature word nodes, such as artifact entities, artifact elements, intent, pros and cons, and others.

artifact, argument, issue, intent) are DR sentence nodes. Other small nodes are feature word nodes, such as artifact entities, artifact elements, intent, pros and cons, and others.

| Literature | DR Representation | Application Field |

|---|---|---|

| [37] | IBIS: issue, position, argument (support or oppose) | political decision processes; general design |

| [44] | DRL: decision problem, alternative, goal, argument, decision, viewpoint, question, DRL relations | general design |

| [38] | QOC: questions, options, and criteria | human–computer interaction |

| [39] | Kuaba: question, idea, reasoning element, artifact, decision, argument, justification | model-based designs, software design |

| [41] | intent, option, justification, decision, operation | engineering design |

| [43] | design intent: artifact, design history, participants, artefact structure, boundary representation | 2D CAD |

| [34] | ISAL: issue, solution, artifact | engineering design |

| [35] | ISAA: issue, solution, argument, artifact and evidence | engineering design |

| [32] | decision, alternative, answer, argument, assumption, decision, procedure, question, requirement | bug reports for software |

| [33] | issue, alternative, criteria, decision, justification | user online reviews for software application |

| [42] | part, assembly, functional requirement, geometry feature, constraint | CAD model |

| [20] | issue, solution (usage, performance, accuracy, product, material, structure, function) | engineering design |

| Literature(?x)^hasArgument(?x,?arg)^hasNegativeWord(?arg,?neg)→hasOpinion(?arg,?neg) Literature(?x)^hasArgument(?x,?arg)^hasPositiveWord(?a,?pos)→hasOpinion(?arg,?pos) | The positive words or pro words contained in the argument sentence represent a supportive opinion about the artifact (design object or solution). Conversely, the negative words or con words contained in the argument sentence of the literature represent an objection opinion to the alternative artifact. |

| Basic_Doc_Unit(?x)^hasIssue(?x,?i)^hasArgumentWord(?i,?neg)→ExpressedAS(?i,?neg) | In the same BDU of the literature, negative words are detailed descriptions of the issue. |

| (Literature(?lit)^hasIntent(?lit,?i1)^hasArtifact(?i1,?a))^(Literature(?lit)^hasIntent(?lit,?i2)^hasArtifact(?i2,?a))→intentIdenticalTo(?i1,?i2) | If intent sentence i1 and intent sentence i2 contain the same artifact elements and the same design intent, the intent sentence i1 is identical_to the intent sentence i2. |

| (Literature(?lit)^hasIssue(?lit,?i1))^(Literature(?lit)^hasIssue(?lit,?i2))→issueIdenticalTo(?i1,?i2) | There is only one major issue in the same document. |

| Literature(?lit)^hasMetadata(?lit,?x)^Basic_Doc_Unit(?y)^hasBDU(?lit,?y) →hasMetadata(?y, ?x) | For the metadata of the literature, they are also the metadata of the BDU of that literature. |

| Literature(?lit)^hasArtifactEntity(?lit,?x)^Comprise(?x,e1)^Literature(?lit)^hasArtifactEntity(?lit,?e2)^swrlb:stringEqualIgnoreCase(?e1,?e2)^sameBDU(?e1,?e2)→ artIdenticalTo(?e1,?e2) | In the BDU of the same document, ArtifactEntity e1 and ArtifactElement e2 are included. If e1 and e2 have equal strings (word or N-gram), then it can be considered that e1 and e2 represent the same artifact, so that the artIdenticalTo relationship can be established. |

| Literature(?lit1)^hasIssue(?lit1,?i1)^Literature(?lit2)^hasIssue(?lit2,?i2)^swrlb:greaterThanOrEqual(?Isim, 0.8)→ issueIdenticalTo(?i1, ?i2) | Literature 1 has issue i1, and literature 2 has issue i2. i1 and i2 have a semantic similarity relationship, and the similarity coefficient Isim ≥ 0.8, then it can be determined that i1 and i2 represent the same issue, so that an issueIdenticalTo relationship can be established. |

| Literature(?lit1)^hasIssue(?lit1,?i1)^Literature(?lit2)^hasIssue(?lit2,?i2)^swrlb:greaterThanOrEqual(?Isim, 0.6)^swrlb:lessThan(?Isim, 0.8)→ issueSimilarTo(?i1, ?i2) | Literature 1 has issue i1, and literature 2 has issue i2. i1 and i2 have a semantic similarity relationship, and 0.6≤ Isim< 0.8. It can be determined that i1 and i2 represent the similar issue, so that an issueSimilarTo relationship can be established. |

| Scope of Fusion | DR Type | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| within a document | issue, intent, alternative, pros and cons | semantic similarity |

| artifacts, pros, cons | word comparison | |

| between documents | issue, intent | semantic similarity |

| literature | citations, co-authors, co-affiliations, and others |

| Relation | Source | Issue |

|---|---|---|

| issueIdenticalTo | Issue 1 in “summary” section | A system and method disclosed herein for providing communications security for small, low-powered systems that are actively and securely controlled over a wireless data link addresses the problems faced by prior art systems. |

| Issue 2 in “background” section | There is therefore a need for a small, low-power, security-certifiable system for controlling actively guided ordinance. | |

| issueSimilarTo | 9194431 | It is this problem that the invention more particularly intends to address, by proposing a new suspension thrust bearing that is simple and economical to manufacture, and to assemble at the same time as guaranteeing a high resistance of the shock absorber bump stop to transmitted shocks. |

| 9664233 | The invention more particularly aims to resolve these problems by proposing a new engagement–disengagement, suspension, or steering release bearing having a greater resistance to a separating force of the rolling bearing rings, while remaining compact. | |

| 9068593 | Against this background, the object of the present invention is to provide a rolling bearing that meets the aforementioned requirements of effective cooling and damping, and that can be produced in a constructionally simple and cost-effective manner. | |

| issueIdenticalTo | 9574630 | The applicant of the present invention has already proposed in JP 2009-197863A an electric linear motion actuator which is free of this problem, and which can sufficiently increase power without the need for a separate speed reduction mechanism, and thus which can be used in an electric disk brake system, of which the linear motion stroke is relatively small. |

| 9188183 | The applicant of the present invention has already proposed in JP 2009-197863A an electric linear motion actuator which is free of this problem, and which can sufficiently increase power without the need for a separate speed reduction mechanism and thus can be used in an electric disk brake system, of which the linear motion stroke is relatively small. | |

| 9435411 | In order to avoid this problem, the applicant of this invention proposed, in JP Patent Publication 2010-65777A and JP Patent Publication 2010-90959A, electric linear motion actuators which are suitable for use in electric disk brake systems, because they can increase power to a considerable degree without the need for a speed reduction mechanism, and are small in linear motion stroke. | |

| 9182021 | The applicant of the present invention has already proposed in JP 2010-65777A and JP 2010-90959A electric linear motion actuators which are free of this problem, and which can sufficiently increase power without the need for a separate reduction mechanism, and thus which can be used in an electric disk brake system, of which the linear motion stroke is relatively small. |

| Literature Source | Info of Argumentation or Thinking | Support Text Mining | Straightforward and Intuitive | Support Knowledge Graph |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [35] | issue, solution, artifact, argument | No | yes (term) | No |

| [20] | issue, solution (usage, performance, accuracy, product, material, structure, function) | N/A | Yes (term) | Yes |

| [42] | part, assembly, functional requirement, geometry feature, constraint | No | N/A | No |

| [43] | artifact, design history, participants, artifact structure, boundary representation | No | Yes (sentence) | yes |

| [34,72] | ISAL: issue, solution, artifact | Yes | No (paragraph) | No |

| Our approach | artifact, issue, intent, pros and cons, alternative, and relation | Yes | Yes (term, phrase, clause, and sentence) | Yes |

| Issue: Maintenance of infrastructure that includes fixtures or other equipment can be difficult, depending on the location of the equipment. … A service person’s limited maneuverability when on a ladder increases the risk of falling or serious injury during a maintenance operation. However, fixtures and other equipment in areas that are difficult to access are prevalent, not only in residential houses, but also in public buildings and public spaces. In other instances, the equipment needs to be powered down before a human can safely perform maintenance thereon. … There is also the issue of scale. As more Internet of Things (IoT) devices such as cameras, chemical sensors, etc., are deployed, there is a need to automate the maintenance of such IoT devices. | |

| Solution: The present invention provides a system for maintaining equipment within a predetermined area, including a first unmanned vehicle configured to perform a diagnostic evaluation of the equipment, a second unmanned vehicle configured to perform a maintenance operation, and a third unmanned vehicle configured to perform a safety operation. … A central control unit is operably coupled to the first unmanned vehicle, the second unmanned vehicle, and the third unmanned vehicle. The central control unit is configured to determine a diagnostic status of the equipment in response to data collected by the first unmanned vehicle, and to dispatch at least one of the second unmanned vehicles, to perform a maintenance operation, and the third unmanned vehicle, to perform a safety operation in response to the diagnostic status of the equipment. | |

| Artifact: | |

| first unmanned vehicle | second unmanned vehicle |

| third unmanned vehicle | central control unit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yue, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, Y. Building a Design-Rationale-Centric Knowledge Network to Realize the Internalization of Explicit Knowledge. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031539

Yue G, Liu J, Zhang Q, Hou Y. Building a Design-Rationale-Centric Knowledge Network to Realize the Internalization of Explicit Knowledge. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(3):1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031539

Chicago/Turabian StyleYue, Gaofeng, Jihong Liu, Qiang Zhang, and Yongzhu Hou. 2023. "Building a Design-Rationale-Centric Knowledge Network to Realize the Internalization of Explicit Knowledge" Applied Sciences 13, no. 3: 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031539

APA StyleYue, G., Liu, J., Zhang, Q., & Hou, Y. (2023). Building a Design-Rationale-Centric Knowledge Network to Realize the Internalization of Explicit Knowledge. Applied Sciences, 13(3), 1539. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13031539