A Study on Exploring the Level of Awareness of Privacy Concerns and Risks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Research

2.1. The Unknown Risks of Platforms and IoT Devices

2.2. Online Social Network Privacy Settings

2.3. Online Privacy and Security Behaviours

2.4. Root Cause of Privacy Leniency

3. Methodology

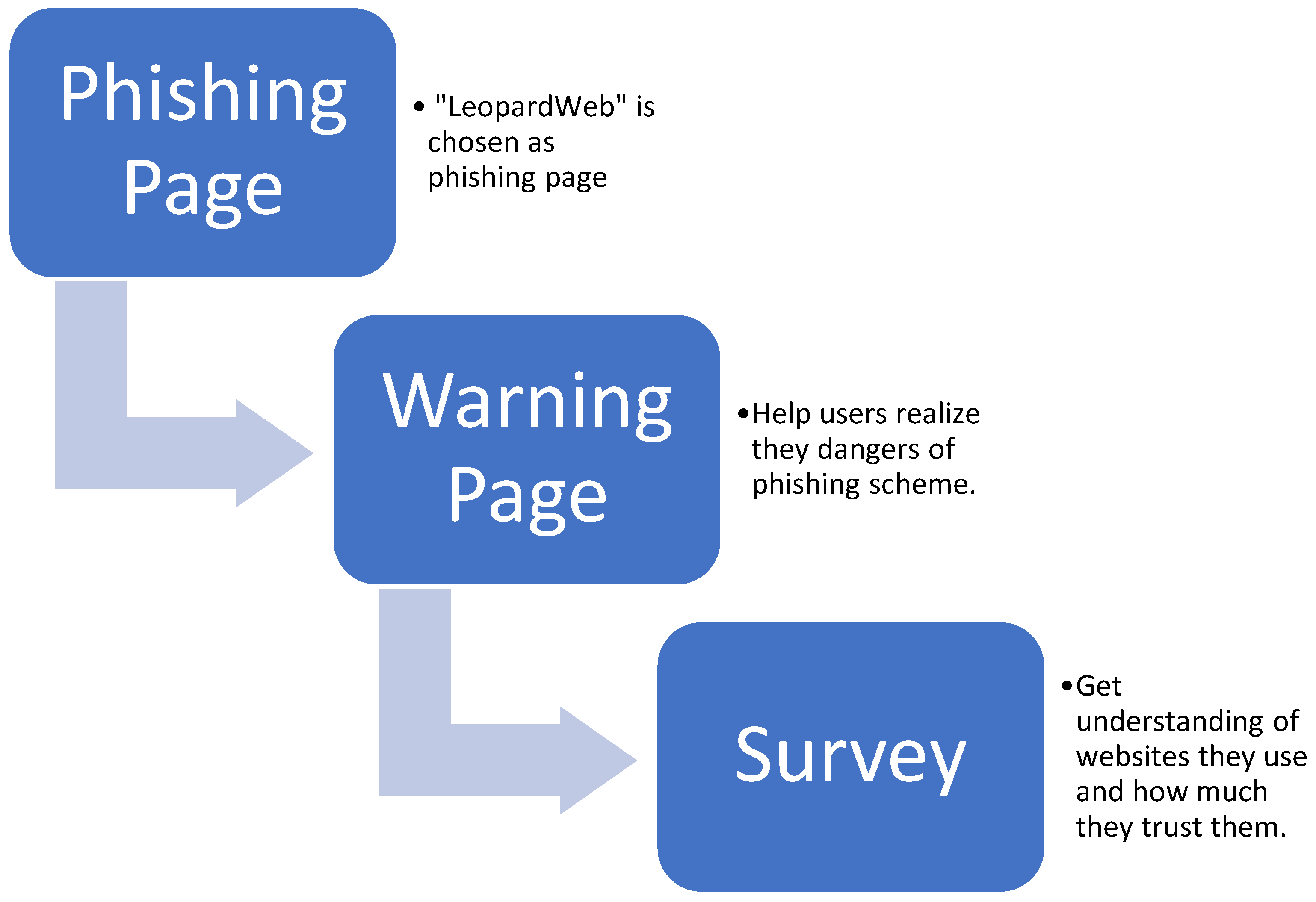

3.1. Proof of Concept WPF Application

3.2. React App Implementation

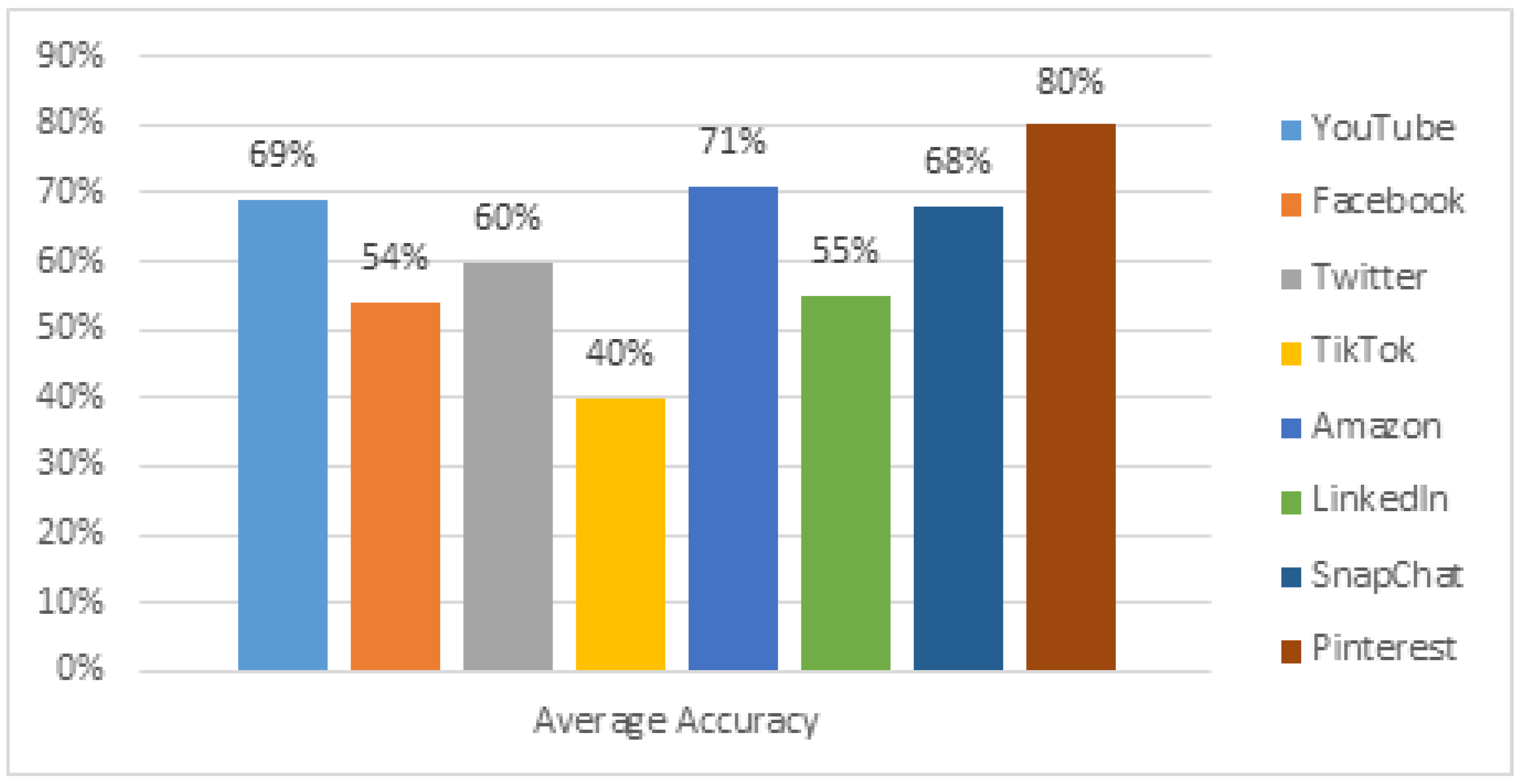

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geraci, G.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A.; Giordano, L.G.; López-Pérez, D.; Björnson, E. Understanding UAV cellular communications: From existing networks to massive MIMO. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 67853–67865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, D.; Lovejoy, J.P.; Ann-Kathrin, H.; Brittany, N.H. Facebook and Online Privacy: Attitudes, Behaviors and Unintended Consequences. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2009, 15, 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Said, W.; Mostafa, A. Towards a hybrid immune algorithm based on danger theory for database security. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 145332–145362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, A.M.V.; Li, Y. A Survey on privacy issues in mobile social networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 130906–130921. [Google Scholar]

- Madejski, M.; Johnson, M.; Bellovin, S. The Failure of Online Social Privacy Settings; Department of Computer Science, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, D. Surveillance as Social Sorting: Privacy, Risk, and Digital Discrimination; Routledge: London, UK, 2003; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Badun, L.; Denney, K.; Celik, Z.B.; McDaniel, P.; Uluagac, A.S. A survey on IoT platforms: Communication security, and privacy perspectives. Comput. Netw. 2021, 192, 108040. [Google Scholar]

- Tclo@ucsc.edu. The Dangers of the Internet of Things. Dangerous World. Available online: https://dangerousworld.soe.ucsc.edu/2018/03/25/the-dangers-of-the-internet-of-things/ (accessed on 25 March 2018).

- Cerruto, F.; Cirillo, S.; Desiato, D.; Gambardella, S.M.; Polese, G. Social network data analysis to highlight privacy threats. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Dabbish, L.; Fruchter, N.; Kiiesler, S. “My data just goes everywhere:” User mental models of the internet and implications for privacy and security. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 22–24 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Breve, B.; Cimino, G.; Deufemia, V. Identifying security and privacy violation rules in trigger-action IoT platforms with NLP models. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 5607–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, G.; Such, J.M. How socially aware are social privacy controls. Computer 2016, 49, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, A.; Al-Arnaout, Z.; Topcu, A.; Zaki, C.; Shdefat, A.; Wlbasi, E. How do default privacy settings on social apps match people’s actual preferences. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Electrical and Computing Technologies and Applications, Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, 23–25 November 2022; pp. 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Cengiz, A.B.; Guler, K.; Boluk, P.S. The effect of social media behaviors on security and privacy threats. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 57674–57684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, S.; Jonh, M.; Junger, M.; Hartel, P.; Roppelt, J. Putting the privacy paradox to the test: Online privacy and security behaviors among users with technical knowledge, privacy awareness, and financial. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 41, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhu, T.; Zhai, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, W. Privacy data propagation and preservation in social media: A real-world case study. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 35, 4137–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Han, M.; Cai, Z. Survey on data analysis in social media: A practical application aspect. Big Data Min. Anal. 2020, 3, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiekermann, S.; Grossklags, J.; Berendt, B. E-privacy in 2nd generation E-commerce: Privacy preferences versus actual behavior. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM conference on Electronic Commerce, Tampa, FL, USA, 14–17 October 2001; pp. 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenseil, P. The One Router Setting Everyone Should Change (But No One Does). Tom’s Guide. Available online: https://www.tomsguide.com/us/change-router-default-passwords,news-26975.html (accessed on 13 April 2018).

- Darmawan, I.; Maulana, M.; Gunawan, R.; Widiyasono, N. Evaluating web scraping performance using XPath, CSS selector, regular expression, and HTML DOM with multiprocessing. Int. J. Inform. Vis. 2022, 6, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopard Web Wentworth Institute of Technology. Available online: https://cas.wit.edu/cas/login (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Meta Privacy Center. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/privacy/policies/cookies/?entry_point=cookie_policy_redirect&entry=0 (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Statement of Right and Responsibilities. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms/previous (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Facebook Terms of Service. Available online: https://m.facebook.com/legal/terms (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Facebook Data Policy. Available online: https://m.facebook.com/privacy/policy/version/20220104/#how-we-use-information (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Amazon Privacy Notice. Available online: https://www.amazon.com.be/-/en/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=GX7NJQ4ZB8MHFRNJ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Interest-Based Ads. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=GLVB9XDF9M8MU7UZ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Conditions of Use. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=GLSBYFE9MGKKQXXM (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- TikTok Privacy Policy. Available online: https://www.tiktok.com/legal/page/us/privacy-policy/en (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- TikTok Terms of Service. Available online: https://www.tiktok.com/legal/page/us/terms-of-service/en (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Linkedin Privacy Policy. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/legal/privacy-policy (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Linkedin User Agreement. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/legal/user-agreement (accessed on 22 June 2023).

- Snap Inc. Custom Creative Tools Terms. Available online: https://snap.com/ar/terms/custom-creative-tools (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Snap Inc. Privacy and Safety Hub. Available online: https://values.snap.com/privacy/privacy-center (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Snap Inc. Cookie Policy. Available online: https://www.snap.com/en-US/cookie-policy (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Twitter Terms of Service. Available online: https://twitter.com/en/tos (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Twitter Privacy Policy. Available online: https://twitter.com/en/privacy (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- YouTube Terms of Service. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/t/terms (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Google Privacy & Terms. Available online: https://policies.google.com/privacy (accessed on 28 June 2023).

- Pinterest Terms of Service. Available online: https://policy.pinterest.com/en/terms-of-service (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Pinterest Privacy Policy. Available online: https://policy.pinterest.com/en/privacy-policy (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Sadq, Z.; Sabir, H.; Saeed, V. Analysing the amazon success strategies. J. Process Manag. New Technol. 2018, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Alzhrani, A.; Alatawi, A.; Alsharari, B.; Albalawi, U.; Mustafa, M. Towards security awareness of mobile application using semantic-based sentiment analysis. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, B.; Townes, S.; Lewis, D.; Bhunia, S. Vulnerability in massive API scraping: 2021 linkedIn data breach. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–17 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Site | Question | Quote | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facebook stores your data whether you have an account or not. | “Facebook uses cookies and receives information when you visit those sites and apps, including device information and information about your activity, without any further action from you. This occurs whether or not you have a Facebook account or are logged in” | [22] | |

| Facebook can view your browser history. | “You can review your Off-Facebook activity, which is a summary of activity that businesses and organizations share with us about your interactions with them, such as visiting their apps or websites. They use our Business Tools, like Facebook Pixel, to share this information with us. This helps us do things like give you a more personalized experience on Facebook” | [22] | |

| Your identity is used in ads that are shown to others. | “You give us permission to use your name and profile picture and information about actions you have taken on Facebook next to or in connection with ads, offers, and other sponsored content that we display across our Products, without any compensation to you.” | [23] | |

| When you delete content on Facebook, it is gone forever. | “In addition, content you delete may continue to appear if you have shared it with others and they have not deleted it.” | [24] | |

| Facebook does not infringe upon/analyse your private messages. | “Our systems automatically process content and communications you and others provide to analyze context and what’s in them for the purposes described below…”

| [25] | |

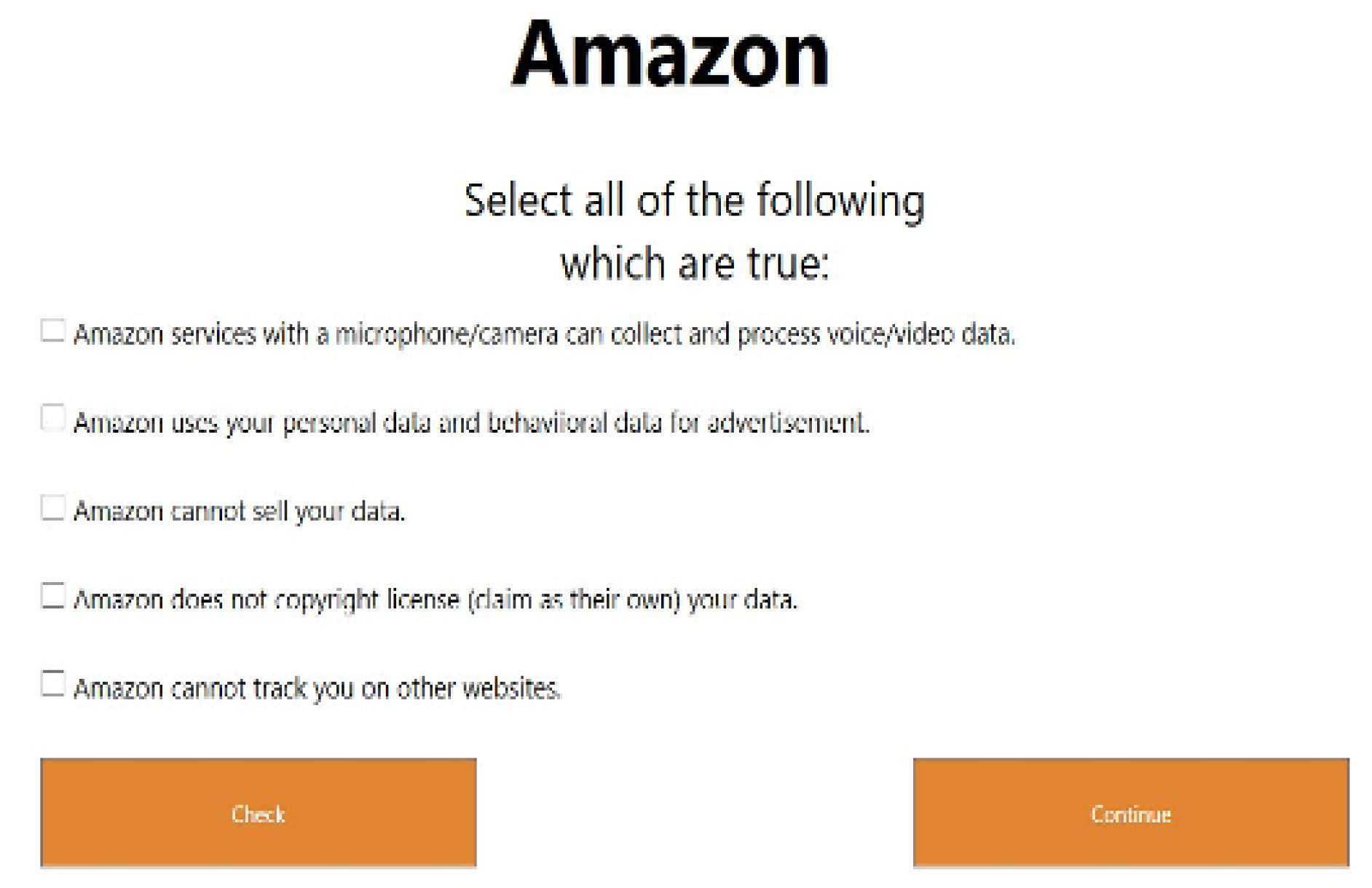

| Amazon | Amazon services with a microphone/camera can collect and process voice/video data. | “When you use our voice, image and camera services, we use your voice input, images, videos, and other personal information to respond to your requests, provide the requested service to you, and improve our services” | [26] |

| Amazon | Amazon can not sell your data. | “As we continue to develop our business, we might sell or buy other businesses or services. In such transactions, customer information generally is one of the transferred business assets but remains subject to the promises made in any pre-existing Privacy Notice (unless, of course, the customer consents otherwise). Also, in the unlikely event that Amazon.com, Inc. or substantially all of its assets are acquired, customer information will of course be one of the transferred assets.” | [26] |

| Amazon | Amazon can not track you on other websites. | “Like many websites, we use “cookies” and other unique identifiers, and we obtain certain types of information when your web browser or device accesses Amazon Services and other content served by or on behalf of Amazon on other websites.” | [26] |

| Amazon | Amazon uses your personal data and behavioural data for advertisement. | “To serve you interest-based ads, we use information such as your interactions with Amazon sites, content, or services.” | [27] |

| Amazon | Amazon does not copyright license (claim as their own) your data. | “If you do post content or submit material, and unless we indicate otherwise, you grant Amazon a nonexclusive, royalty-free, perpetual, irrevocable, and fully sublicensable right to use, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, perform, translate, create derivative works from, distribute, and display such content throughout the world in any media. You grant Amazon and sublicensees the right to use the name that you submit in connection with such content, if they choose.” | [28] |

| TikTok | Private messages can not be read by the service. | “Messages: We collect and process, which includes scanning and analyzing, information you provide when you compose, send, or receive messages through the Platform’s messaging functionality. That information includes the content of the message and information about when the message has been sent, received and/or read, as well as the participants of the communication.” | [29] |

| TikTok | Information such as age, username/password, email, phone number can be collected by TikTok. | “Information, such as age, username and password, language, and email or phone number. Profile information, such as name, social media account information, and profile image. User-generated content, including comments, photographs, live streams, audio recordings, videos, and virtual item videos that you choose to create with or upload to the Platform.” | [29] |

| TikTok | Data on your content is collected at the time of creation, regardless of if you choose to upload or save it. | “We collect User Content through pre-loading at the time of creation, import, or upload, regardless of whether you choose to save or upload that User Content, in order to recommend audio options and provide other personalized recommendations.” | [29] |

| TikTok | Some browsers transmit “do-not-track” signals to websites. TikTok ignores these. | “Some browsers transmit “do-not-track” signals to websites. Because of differences in how browsers incorporate and activate this feature, we currently do not take action in response to these signals” | [29] |

| TikTok | Your content can be deleted at any time without prior notice for any reason. | “We reserve the right, at any time and without prior notice, to remove or disable access to content at our discretion for any reason or no reason.” | [30] |

| LinkedIn stores data on you even if you did not interact with the service. | “We receive personal data (including contact information) about you when others import or sync their contacts or calendar with our Services, associate their contacts with Member profiles, scan and upload business cards, or send messages using our Services” | [31] | |

| The LinkedIn mobile app can scan both your contacts and your calendar. | “If you opt to import your address book, we receive your contacts (including contact information your service provider(s) or app automatically added to your address book when you communicated with addresses or numbers not already in your list). If you sync your contacts or calendars with our Services, we will collect your address book and calendar meeting information to keep growing your network” | [31] | |

| Your private messages cannot be scanned/read. | “We also use automatic scanning technology on messages to support and protect our site. For example, we use this technology to suggest possible responses to messages and to manage or block content that violates our User Agreement or Professional Community Policies from our Services” | [31] | |

| Your identity can not be used in ads that are shown to other users. | “we have the right, without payment to you or others, to serve ads near your content and information, and your social actions (e.g., likes, comments, follows, shares may be visible and included with ads, as noted in the Privacy Policy). If you use a Service feature, we may mention that with your name or photo to promote that feature within our Services, subject to your settings” | [32] | |

| Specific content can be removed without reason or notice. | “We are not obligated to publish any information or content on our Service and can remove it with or without notice” | [32] | |

| Snapchat | The service can edit and distribute your content through any media known now or that may exist in the future. | “You grant Snap and its affiliates a license to archive, copy, cache, encode, store, reproduce, record, sell, sublicense, distribute, transmit, broadcast, synchronize, adapt, edit, modify, publicly display, publicly perform, publish, republish, promote, exhibit, create derivative works based upon, and otherwise use the Asset on or in connection with the Services and the advertising, marketing, and promotion thereof, in all formats, on or through any means or media now known or hereafter developed, and with any technology or devices now known or hereafter developed” | [33] |

| Snapchat | Snapchat does not hold onto content that you have deleted. | “After a Snap is deleted, we’ll mainly be able to see the basic details—like when it was sent and who it was sent to.” | [34] |

| Snapchat | Your personal data is not given to third parties that work for Snapchat. | “We may share information about you with business partners that provide services and functionality on our services” | [34] |

| Snapchat | Snapchat may not only collect your location data, but they can also use it and share it. | “provide and improve our advertising services, ad targeting, and ad measurement, including through the use of your precise location information (again, if you’ve given us permission to collect that information)” | [35] |

| Snapchat | Snapchat can not share your personal data with third parties that are not involved in its operation. | “We may let other companies use cookies on our services. These companies may collect information about how you use our services over time and combine it with similar information from other services and companies.” | [35] |

| Users own the content they submit, post or display on Twitter. | “You retain your rights to any Content you submit, post or display on or through the Services. What’s yours is yours—you own your Content (and your incorporated audio, photos and videos are considered part of the Content).” | [36] | |

| Twitter is licensed to use your Content without restrictions. | “By submitting, posting or displaying Content on or through the Services, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content in any and all media or distribution methods now known or later developed” | [36] | |

| Twitter collects information outside of the app on your devices. | “Information about your connection, such as your IP address and browser type. Information about your device and its settings, such as device and advertising ID, operating system, carrier, language, memory, apps installed, and battery level. Your device address book, if you’ve chosen to share it with us.” | [37] | |

| Twitter collects information on non-user activity within the products and services. | “We may receive information when you view content on or otherwise interact with our products and services, even if you have not created an account or are signed out, such as IP address; browser type and language; operating system; the referring webpage; access times; pages visited; location; your mobile carrier; device information (including device and application IDs); search terms and IDs (including those not submitted as queries); ads shown to you on Twitter; Twitter-generated identifiers; and identifiers associated with cookies. | [37] | |

| Information collected by Twitter will be removed from the web after deleting an account. | “Remember public content can exist elsewhere even after you remove it from Twitter. For example, search engines and other third parties may retain copies of your Tweets longer, based upon their own privacy policies, even after they are deleted or expire on Twitter.” | [37] | |

| YouTube/Google | The service will retain your Content after you remove it. | “The licenses granted by you continue for a commercially reasonable period of time after you remove or delete your Content from the Service. You understand and agree, however, that YouTube may retain, but not display, distribute, or perform, server copies of your videos that have been removed or deleted.“ | [38] |

| YouTube/Google | The service is able to use and modify your Content to their discretion. | “By providing Content to the Service, you grant to YouTube a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free, sublicensable and transferable license to use that Content (including to reproduce, distribute, prepare derivative works, display and perform it) in connection with the Service and YouTube’s (and its successors’ and Affiliates’) business, including for the purpose of promoting and redistributing part or all of the Service.” | [38] |

| YouTube/Google | The service obtains and stores location information from the device you’re using. | “Your location can be determined with varying degrees of accuracy by: GPS and other sensor data from your device, IP address, and activity on Google services, such as your searches and places you label like home or work. As well as information about things near your device, such as Wi-Fi access points, cell towers, and Bluetooth-enabled devices.” | [39] |

| YouTube/Google | The service can relocate your data to outside of your country. | “We maintain servers around the world and your information may be processed on servers located outside of the country where you live. Data protection laws vary among countries, with some providing more protection than others.” | [39] |

| Pinterest does not retain Content that has been removed. | “Following termination or deactivation of your account, or if you remove any User Content from Pinterest, we may keep your User Content for a reasonable period of time for backup, archival, or audit purposes. Pinterest and its users may retain and continue to use, store, display, reproduce, re-pin, modify, create derivative works, perform, and distribute any of your User Content that other users have stored or shared on Pinterest.” | [40] | |

| Pinterest does not track your location when you choose not to share your precise location. | “We will still use your IP address, which is used to approximate your location, even if you don’t choose to share your precise location.” | [41] | |

| Pinterest does not transfer or store data outside of your country. | “By using our products or services, you authorize us to transfer and store your information outside your home country, including in the United States, for the purposes described in this policy.” | [41] | |

| Content you post is available to the public. | “Anyone can see the public boards and Pins you create and profile information you give us. We also make this public information available through what are called APIs (basically a technical way to share information quickly).” | [41] | |

| Pinterest does not receive your information from outside of Pinterest. | “We also get information about you and your activity outside Pinterest from our affiliates, advertisers, partners and other third parties we work with.” | [41] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.; Yeates, G.; Ly, T.; Albalawi, U. A Study on Exploring the Level of Awareness of Privacy Concerns and Risks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13237. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132413237

Nguyen T, Yeates G, Ly T, Albalawi U. A Study on Exploring the Level of Awareness of Privacy Concerns and Risks. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(24):13237. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132413237

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Tommy, Garnet Yeates, Tony Ly, and Umar Albalawi. 2023. "A Study on Exploring the Level of Awareness of Privacy Concerns and Risks" Applied Sciences 13, no. 24: 13237. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132413237

APA StyleNguyen, T., Yeates, G., Ly, T., & Albalawi, U. (2023). A Study on Exploring the Level of Awareness of Privacy Concerns and Risks. Applied Sciences, 13(24), 13237. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132413237