The problem of quantitatively assessing the vast amounts of data in modern multimedia content has been addressed for decades, first for the purpose of content indexing and retrieval and later for content-based recommender systems (CBRS). We hypothesize that similar dimensionality reduction tools originally used for indexing and CBRS can also be used to determine the impact of content on multimedia engagement scales.

Many user-based multimedia classification systems utilize high-level content features, such as genre, director, cast, tags, text reviews, and similar meta-information [

19]. These metadata annotations are scarce, particularly for video advertising, and implicit metadata available through computational analysis of the content are preferred. Therefore, the main goal of the presented research is to relate an individual’s measurable content engagement to the computable features of the multimedia content consumed. We begin our presentation of potential feature sets with a standardized and widely used set of low-level descriptors for visual multimedia content, a subset of which can be algorithmically extracted.

2.2.1. MPEG-7

The MPEG-7 represents a well-established set of semantic and descriptive features that help manage, search, analyze, and understand modern multimedia content. Multimedia in the form of large numeric datasets poses a challenge to their interpretation due to the lack of efficient identification techniques that deal with large datasets at the specific level of content description defined by the context of a current application. A higher-level, yet generic set of media record descriptors that would reduce the size of the original content notation would be helpful. These descriptors can be determined manually or by automatic content analysis and preprocessing. The established MPEG7 [

20,

21] standard addresses generic media record descriptors for indexing and searching multimedia databases, and has traditionally been used as a tool for indexing, searching, and accessing the desired multimedia content.

MPEG-7 comprises a family of standards for multimedia content description and is defined by ISO/IEC 15938 [

20]. Unlike its predecessors, the standard is not intended to encode audiovisual material but to describe it. Metadata about the material is stored in XML format and provides an accurate description that can be used to mark individual segments related to events in the material with a time code. This standard was developed to allow users to quickly and efficiently retrieve multimedia materials they need. It can be used independently of other MPEG standards and is closely related to the nature of the audiovisual material, as defined in MPEG-7. The MPEG-7 architecture states that multimedia content descriptions must be kept separate and the relationships between them must be unambiguously preserved. MPEG-7 is based on four basic building blocks:

Descriptors (metadata extracted from multimedia materials),

Description Schemes (structures and semantics of description relationships),

Description Definition Language (DDL) (a language that allows you to create and add new description schemas and descriptions), and

System Tools (tools that support description multiplexing, content synchronization, downloading, record encoding, and intellectual property protection).

MPEG-7 contains 13 volumes, of which Part 3 contains tools for visual content description, namely, static images, videos, and 3D models. Descriptions of the visual features defined by the standard include color, texture, shape, and motion, as well as object localization and face recognition, each of which is multi-dimensional. Specifically, the core MPEG-7 visual descriptors are Color Layout, Color Structure, Dominant Color, Scalable Color (color), Edge Histogram, Homogeneous Texture, Texture Browsing (texture), Region-based Shape, Contour-based Shape (shape), Camera Motion, Parametric Motion, and Motion Activity (motion). Other descriptors represent structures for aggregation and localization and include core descriptor aggregates with additional semantic information. These include Scalable Color descriptions (Group-of-Frames/Group-of-Pictures), 3D mesh information (Shape 3D), object segmentation in subsequent frames (Motion Trajectory) and specific face extraction results (Face Recognition), Spatial 2D Coordinates, Grid Layout, Region Locator, Time Series, Temporal Interpolation and Spatio-Temporal Locator. The remaining set of aggregated descriptors contains supplementary (textual) structures in color spaces, color quantization, and multiple 2D views of 3D objects. Some of these descriptors can be obtained using automated image analysis [

22].

The visual features of MPEG-7 have relatively high dimensionality because each feature is a vector. Studies also demonstrated a high degree of redundancy in MPEG-7 visual features [

23]. The MPEG-7 features are standardized, well-structured, computationally available, and provide a good basis for indexing, searching, and querying multimedia content. Some key computable features are represented in great detail (e.g., color and texture), whereas other media aesthetic elements are not directly covered. However, there is no commonly known direct interpretation of MPEG-7 visual features in terms of arousal triggered by media consumers.

2.2.2. Stylistic Video Features

Research on applied media aesthetics demonstrates that the effects of production techniques on viewers’ aesthetic reflexes can be evaluated computationally, based on the aesthetic elements of multimedia items [

24]. For example, [

24] described how the basic elements of media aesthetics can be used to produce maximally effective visual appeal of images and videos. Another study on multimedia services demonstrated filtering of large information spaces to classify the attractiveness of multimedia items to users [

25]. Other researchers have recommended the use of automatically extracted low-level features in hybrid and autonomous recommender systems [

26,

27]. We hypothesize that the knowledge of individuals’ subjective responses to multimedia content, based on low-level features from applied media aesthetics [

24] and recommender systems [

26,

27] can be extended to multimedia exposure.

The elements of media aesthetics refer to the use of light, colors, screen area, depth, and volume in the three-dimensional realm, time, and movement in videos. The expressive communication of movie producers is based on established design rules, also known as movie grammar. Ref. [

28] identified the elements of movie grammar using computable video features to identify the movie genre based on video previews. Their proposal included lightning key, color variance, motion content, and average shot length features along with a well-described algorithm for determining each feature. An improved proposal for aesthetically inspired descriptors applied to a movie recommendation system was presented by Deldjoo et al. [

26] and is called

stylistic video features. We adopted a basic set of visual features related to color, illuminance, object motion, and shot tempo of the video sequence, as described below.

Lighting Key is a powerful tool used by directors to control the emotions evoked by video consumers [

26,

28]. The use of

high-key lighting, where less contrast is used, resulting in bright images, promotes positive and optimistic responses. The use of dark shading, resulting in low mean and standard deviation grayscale, creates a mysterious and dramatic mood typical of noir movies; this is known as

low-key lighting. The Lighting Key

of a frame is defined as the product of the mean

and standard deviation

of the brightness component (

V) in the three-dimensional color space

,

Typically, high values of both the mean and standard deviation of brightness are associated with funny video scenes, which may be associated with

. On the other hand, dark, dramatic scenes indicate the opposite situation, where

. In some video materials, where

lighting key is less pronounced, which directly affects viewer mood [

26].

The Lighting Key value for an entire video is defined as the average of

. To speed up the calculations, we can take the middle frame of each shot as a representative value, resulting in

Color Variance is another indicator closely related to the mood that a director intends to express with the video [

26,

28]. Color Variance is a scalar dimension that indicates how vibrant a movie’s color palette is. Lighter colors are generally used in light and funny videos, whereas darker colors are predominant in horror and morbid scenes.

We can calculate the Color Variance in the three-dimensional color space

using the covariance matrix of the three color dimensions. The value of the Color Variance per frame is equal to

The Final Color Variance value for the entire video is the average of

using the representative key frames of each shot, resulting in

Motion Activity within a video refers to movements of the camera or objects within the scene. The shot and cut dynamics are also included to a certain degree in the Average Shot Length video features described in the next subsection. However, object dynamics remain an independent feature related to viewers’ feelings evoked by videos. Some early studies used MPEG motion vectors in the compression domain to obtain motion information of a video [

29]. Ref. [

28] uses a method based on

visual disturbance of the image sequence. Ref. [

26] proposes to characterize motion activity using optical flow [

30], which indicates the velocity of objects in a sequence of images. According to their proposal, both the mean value of the pixel motions

and standard deviation of pixel motions

can be applied as motion features of a video.

Average Shot Length is defined as the average of the shot duration

where

is the number of frames and

is the number of shots in the entire video being evaluated. This ratio provides a good estimate of the tempo of the scenes, which is controlled by the video director. This feature was introduced and evaluated in depth by [

31] and was later used by [

26,

28]. There are many algorithms for automatic scene transition detection that are well described in [

28,

31]. Well-known techniques for scene detection include content-based, adaptive-, and threshold-based scene detectors. These three techniques are used in an open-source scene detection tool

PySceneDetect hosted on GitHub [

32]. The content-aware method detects jump cuts within a video and is triggered when the difference between two consecutive frames exceeds a predefined threshold. It operates in the HSV color space across all three color channels. The adaptive method works in a similar manner but uses the moving average of several adjacent changes to reduce the detection of false scene transitions in the case of fast camera movements. The threshold method is the most traditional method which, according to PySceneDetect, triggers a scene cut when the brightness of an image falls below a predefined threshold (fade-out).

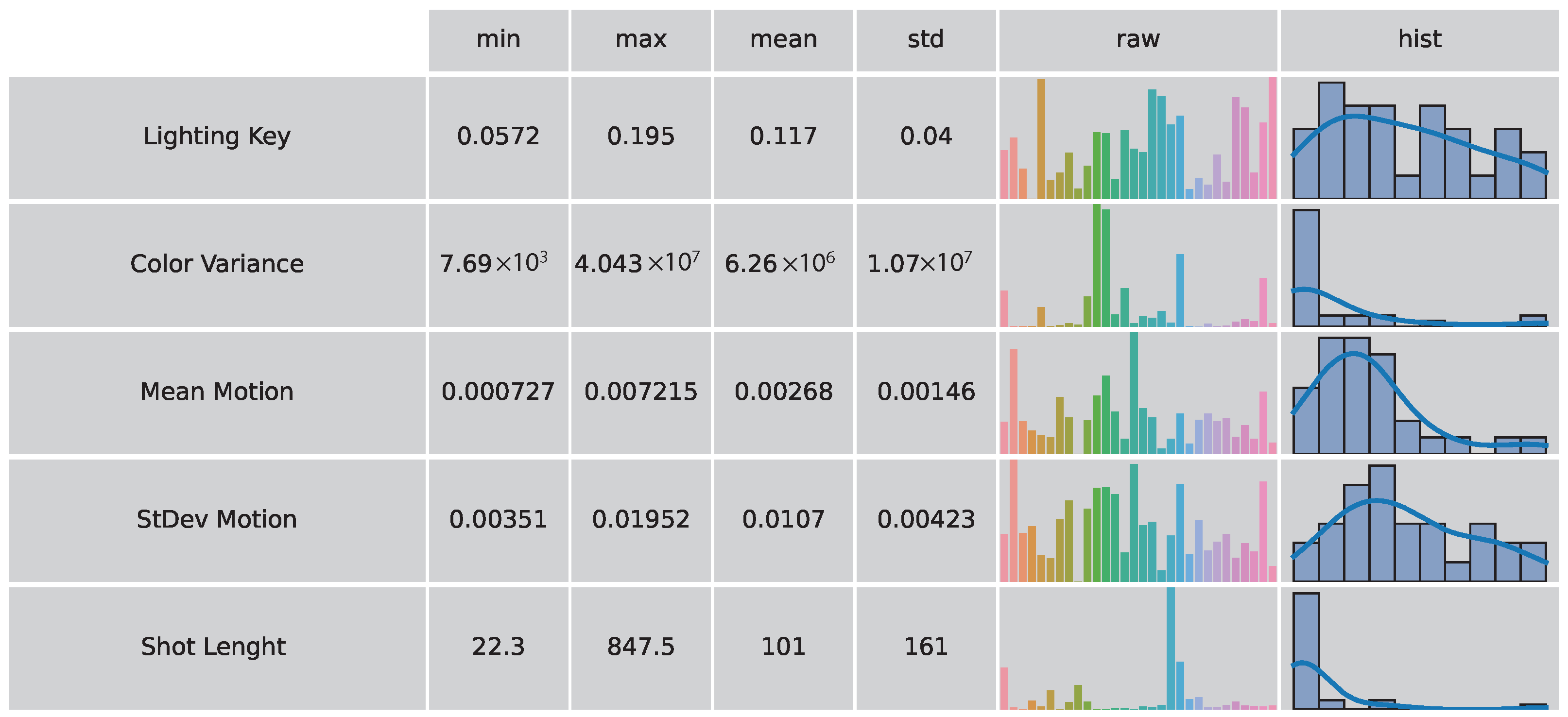

The five presented video features represent a good estimate of the stylistic video features and together they form a video feature vector

comprised of Lighting Key, Color Variance, Average Shot Length, Mean Motion Activity and Standard Deviation of Motion Activity.

At this early stage of development, we decided to use more explanatory and compact stylistic video features rather than MPEG-7. The above feature vector

was therefore used in our study. A collection of related work findings is assembled in

Table 2.