The Most Important Risk Factors Affecting the Physical Health of Orthodontists: A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Questionnaire

2.2. Statistical Analysis

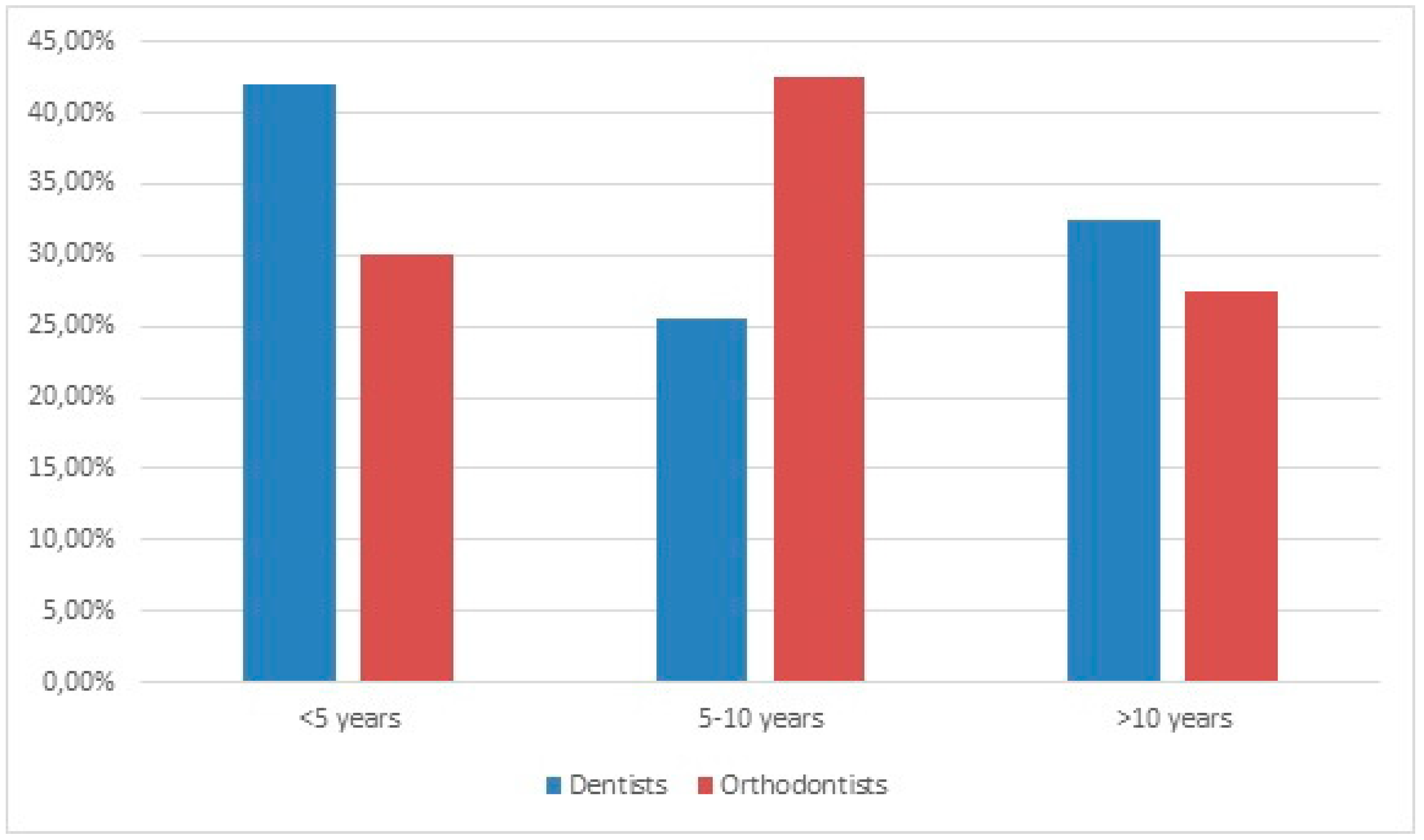

3. Results

3.1. The Health Status of Dentists and Orthodontists

3.2. Peculiarities of Ergonomics in the Work of Dental Specialists

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, A.; Ankola, A.V.; Hebbal, M. Dental Ergonomics to Combat Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Review. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2013, 19, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Bhat, M.; Mohammed, T.; Bansal, N.; Gupta, G. Ergonomics in Dentistry. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2014, 7, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vodanović, M.; Galić, I.; Kelmendi, J.; Chalas, R. Occupational health hazards in contemporary dentistry—A review. Rad Hrvat. Akad. Znan. Umjetnosti. Med. Znan. 2017, 44, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, C.; Bocchieri, S.; De Stefano, R.; Gorassini, F.; Surace, G.; Amoroso, G.; Scoglio, C.; Mastroieni, R.; Gambino, D.; Amantia, E.M.; et al. Dental Office Prevention of Coronavirus Infection. Eur. J. Dent. 2020, 14, S146–S151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahi, H.R.; Keyhan, S.O.; Zandian, D.; Kim, S.G.; Cheshmi, B. Being a front-line dentist during the COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2020, 42, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinabadi, M.S.; Safaian, G.; Mirmohammadkhani, O.; Mirmohammadkhani, M.; Ameli, N. Evaluation of Health-Related Quality of Life among Dentists in Semnan, Iran, 2015–2016. Middle East J. Rehabil. Health Stud. 2018, 5, e83626. [Google Scholar]

- Vodanović, M.; Sović, S.; Galić, I. Occupational Health Problems among Dentists in Croatia. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2016, 50, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejčić, N.; Petrović, V.; Marković, D.; Miličić, B.; Dimitrijević, I.; Perunović, N.; Čakić, S. Assessment of risk factors and preventive measures and their relations to work-related musculoskeletal pain among dentists. Work 2017, 57, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbin, A.J.Í.; Barreto Soares, G.; Moreira Arcieri, R.; Garbin, C.A.S.; Siqueira, C.E. Musculoskeletal disorders and perception of working conditions: A survey of Brazilian dentists in São Paulo. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2017, 30, 367–377. [Google Scholar]

- Bruers, J.J.M.; Trommelen, L.E.C.M.; Hawi, P.; Brand, H.S. Musculoskeletal disorders among dentists and dental students in the Netherlands. Ned. Tijdschr. Tandheelkd. 2017, 124, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šćepanović, D.; Klavs, T.; Verdenik, I.; Oblak, Č. The Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Pain of Dental Workers Employed in Slovenia. Workplace Health Saf. 2019, 67, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalappa, S.; Shankar, R. A study on the influence of ergonomics on the prevalence of chronic pain disorders among dentists. Int. Surg. J. 2017, 4, 3873–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Natheer, A.R.; Hiba, E.K.; Lin, R.; Maryam, E.L.; Rawand, N.; Reem, Y.; Sausan, A.K. Musculoskeletal Pain among Different Dental Specialists in United Arab Emirates. OHDM 2016, 15, 292–298. [Google Scholar]

- Taib, M.F.M.; Bahn, S.; Yun, M.H.; Taib, M.S.M. The effects of physical and psychosocial factors and ergonomic conditions on the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dentists in Malaysia. Work 2017, 57, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakzewski, L.; Naserud-Din, S. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Australian dentists and orthodontists: Risk assessment and prevention. Work 2015, 52, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Sepúlveda, K.A.; Gómez-Arias, M.Y.; Agudelo-Suárez, A.A.; Ramírez-Ossa, D.M. Musculoskeletal disorders and related factors in the Colombian orthodontists’ practice. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bruyne, M.; Van Renterghem, B.; Baird, A.; Palmans, T.; Danneels, L.; Dolphens, M. Influence of different stool types on muscle activity and lumbar posture among dentists during a simulated dental screening task. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 56, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Grado, G.F.; Denni, J.; Musset, A.M.; Offner, D. Back pain prevalence, intensity and associated factors in French dentists: A national study among 1004 professionals. Eur. Spine J. 2019, 28, 2510–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, A.J.; Gada, V.H.; Manda, A.M.; Joshi, A.N.; Chaudhari, P.R.; Toshniwal, D.G. Dental operator‘s posture and position. Int. J. Dent. Health Sci. 2015, 2, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Ahearn, D.J.; Sanders, M.J.; Turcotte, C. Ergonomic design for dental offices. Work 2010, 35, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakzewski, L.; Naserud-Din, S. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in dentists and orthodontists: A review of the literature. Work 2014, 48, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voudouris, J.C.; Suri, S.; Tompson, B.; Voudouris, J.D.; Schismenos, C.; Poulos, J. Self-ligation shortens chair time and compounds savings, with external bracket hygiene compared to conventional li-gation: Systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dent. Oral Craniofac. Res. 2018, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamukçu, H.; Özsoy, O.P. Indirect Bonding Revisited. Turk. J. Orthod. 2016, 9, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glisic, O.; Hoejbjerre, L.; Sonnesen, L. A comparison of patient experience, chair-side time, accuracy of dental arch measurements and costs of acquisition of dental models. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bud, M.; Jitaru, S.; Lucaciu, O.; Korkut, B.; Dumitrascu-Timis, L.; Ionescu, C.; Cimpean, S.; Delean, A. The advantages of the dental operative microscope in restorative dentistry. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2021, 94, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Problem | Neck Pain | Shoulder Girdle Pain | Back Pain | Chest Pain | Low Back Pain | Wrist Pain | Hands and Fingers Pain and Numbness | Leg Pain | Headache | Eye Fatigue | General Physical Fatigue | Allergies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | |||||||||||||

| Every day, n (%) | 38 (12.1) | 48 (15.2) | 51 (16.2) | 4 (1.3) | 32 (10.2) | 12 (3.8) | 12 (3.8) | 10 (3.2) | 9 (2.9) | 62 (19.7) | 64 (20.3) | 20 (6.3) | |

| At least once a week, n (%) | 103 (32.7) | 95 (30.2) | 112 (35.6) | 13 (4.1) | 67 (21.3) | 34 (10.8) | 30 (9.5) | 19 (6.0) | 95 (30.2) | 92 (29.2) | 129 (4.0) | 12 (3.8) | |

| Less than once a week, n (%) | 63 (20.0) | 67 (21.3) | 68 (21.6) | 28 (8.9) | 80 (25.4) | 51 (16.2) | 33 (10.5) | 37 (11.7) | 112 (35.6) | 87 (27.6) | 76 (24.1) | 27 (8.6) | |

| Less than once a month, n (%) | 74 (23.5) | 73 (23.2) | 69 (21.9) | 64 (20.3) | 75 (23.8) | 128 (40.6) | 111 (35.2) | 99 (31.4) | 74 (23.5) | 51 (16.2) | 41 (13.0) | 78 (24.8) | |

| Never encountered, n (%) | 37 (11.7) | 32 (10.2) | 15 (4.8) | 206 (65.4) | 61 (19.4) | 90 (28.6) | 129 (41.0) | 150 (47.6) | 25 (7.9) | 23 (7.3) | 5 (1.6) | 178 (56.5) | |

| N—number of cases | |||||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trakiniene, G.; Rudzinskaite, M.; Gintautaite, G.; Smailiene, D. The Most Important Risk Factors Affecting the Physical Health of Orthodontists: A Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031087

Trakiniene G, Rudzinskaite M, Gintautaite G, Smailiene D. The Most Important Risk Factors Affecting the Physical Health of Orthodontists: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(3):1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031087

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrakiniene, Giedre, Monika Rudzinskaite, Greta Gintautaite, and Dalia Smailiene. 2022. "The Most Important Risk Factors Affecting the Physical Health of Orthodontists: A Pilot Study" Applied Sciences 12, no. 3: 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031087

APA StyleTrakiniene, G., Rudzinskaite, M., Gintautaite, G., & Smailiene, D. (2022). The Most Important Risk Factors Affecting the Physical Health of Orthodontists: A Pilot Study. Applied Sciences, 12(3), 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031087