Sliding Mode Path following and Control Allocation of a Tilt-Rotor Quadcopter

Abstract

1. Introduction

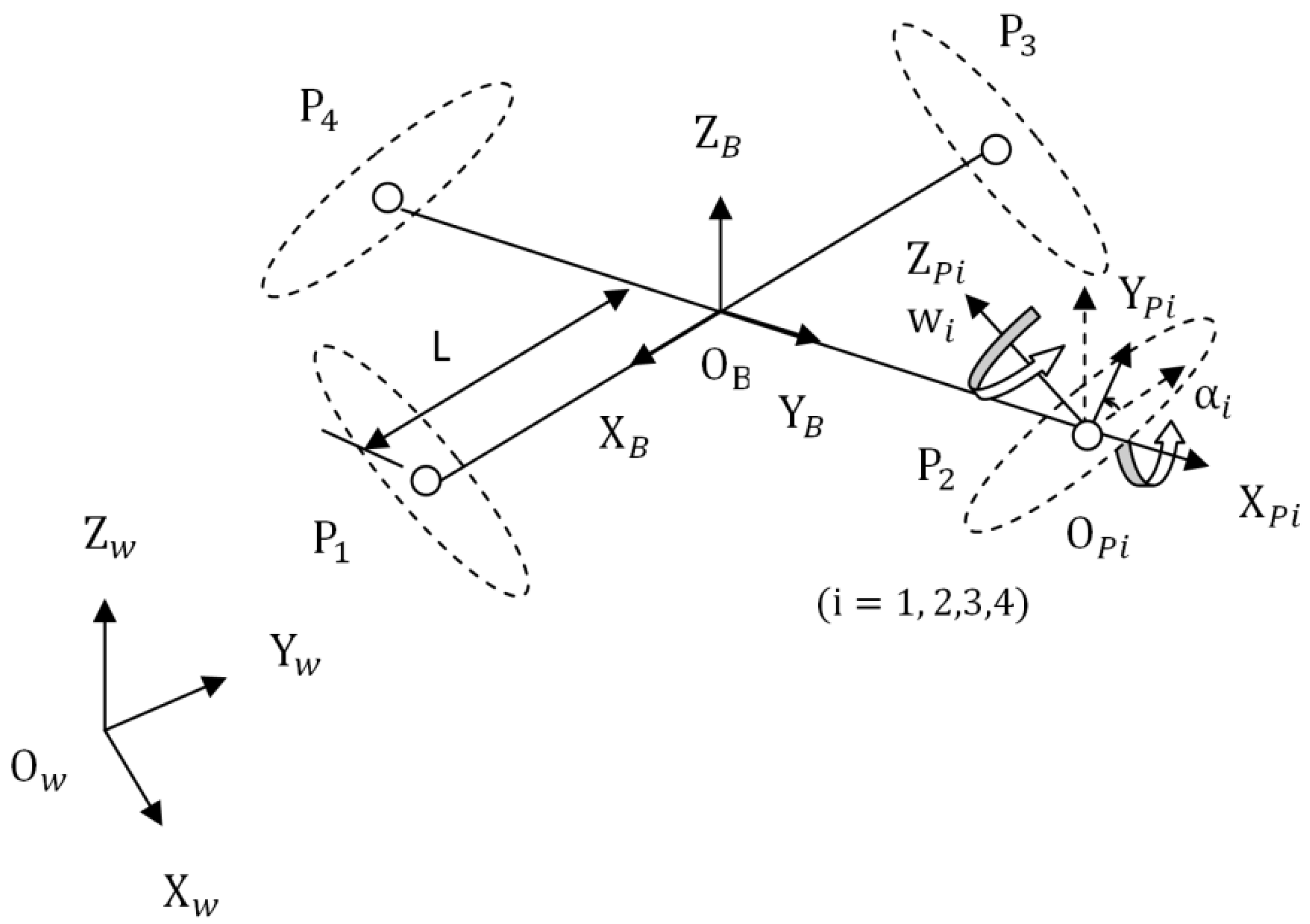

2. Dynamic Model of a Tilt-Rotor Quadcopter (TRQ) with Various Actuation Modes

2.1. Rotational and Translational Dynamics

2.2. Over-Actuated, Fully Actuated, and Under-Actuated Modes

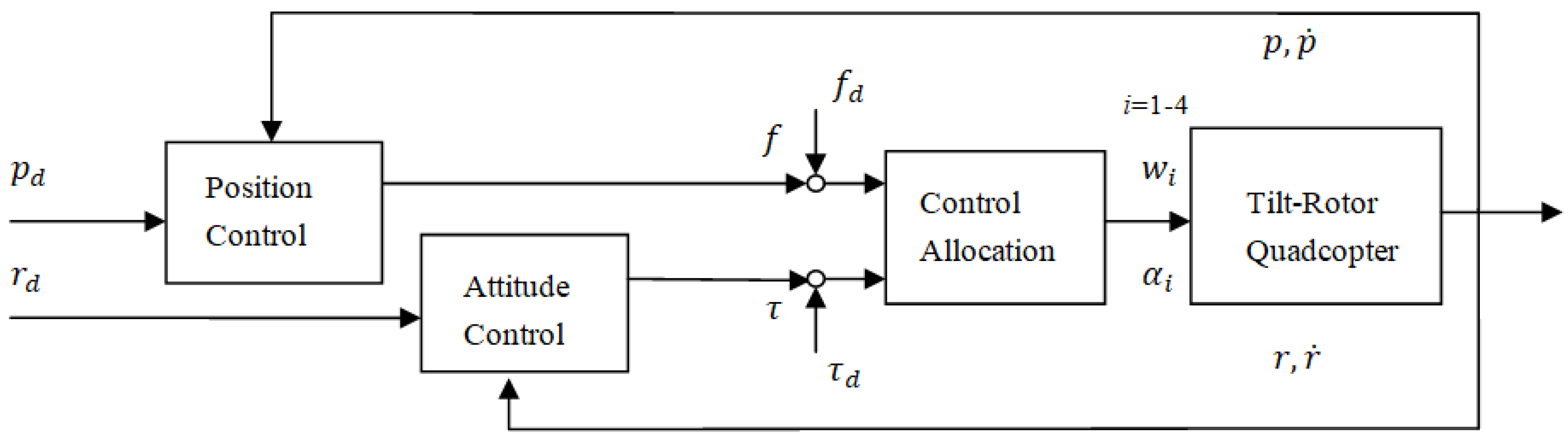

3. Sliding Mode Path following and Control Allocation

3.1. Attitude and Position following SMC

3.2. Control Allocation

3.2.1. Fully Actuated Mode

3.2.2. Over-Actuated Mode

3.2.3. Under-Actuated Mode

4. Stability Analysis

4.1. Sliding Mode Attitude following Control

4.2. Sliding Mode Position following Control

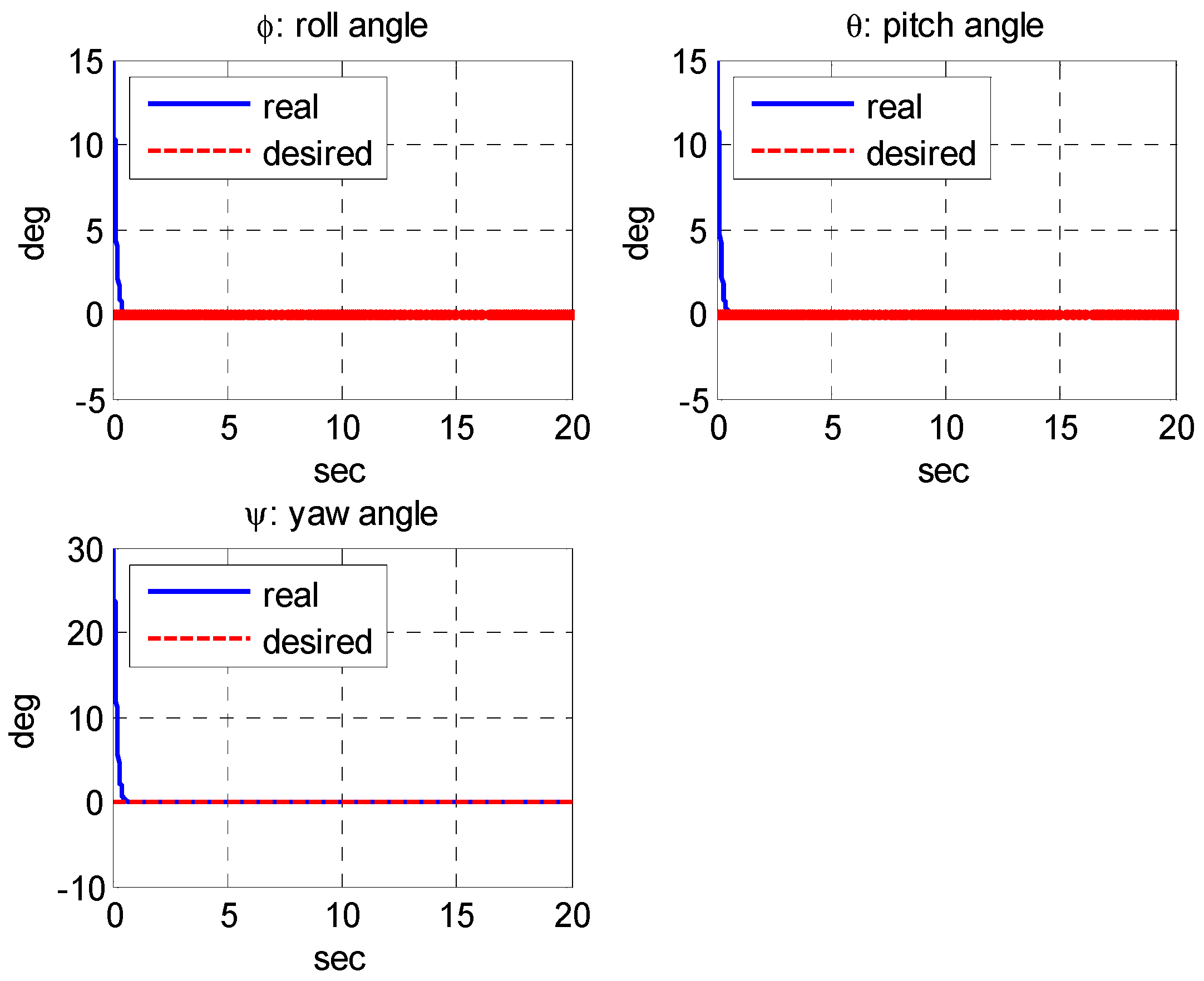

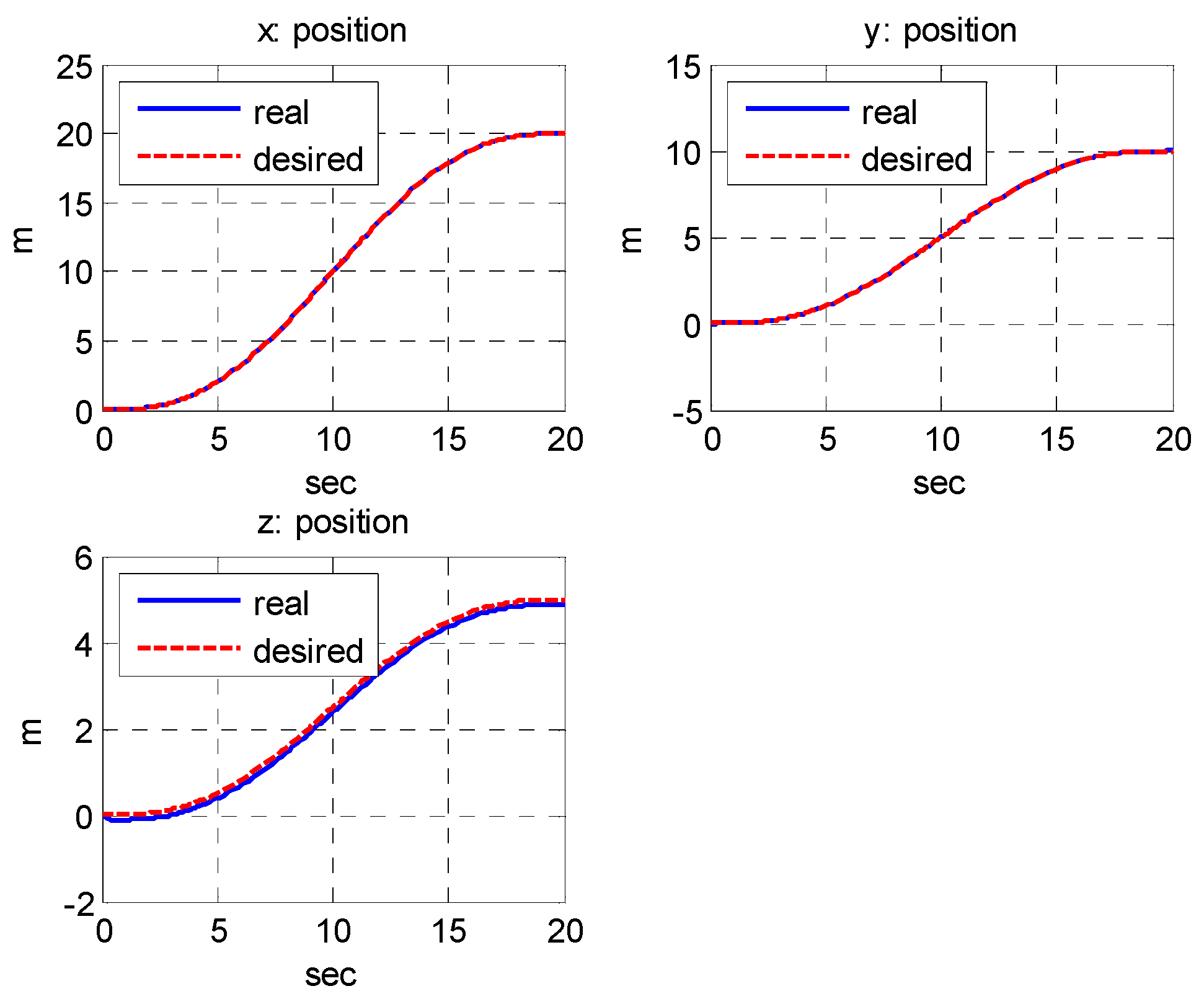

5. Numerical Simulation

5.1. Simulation Parameters

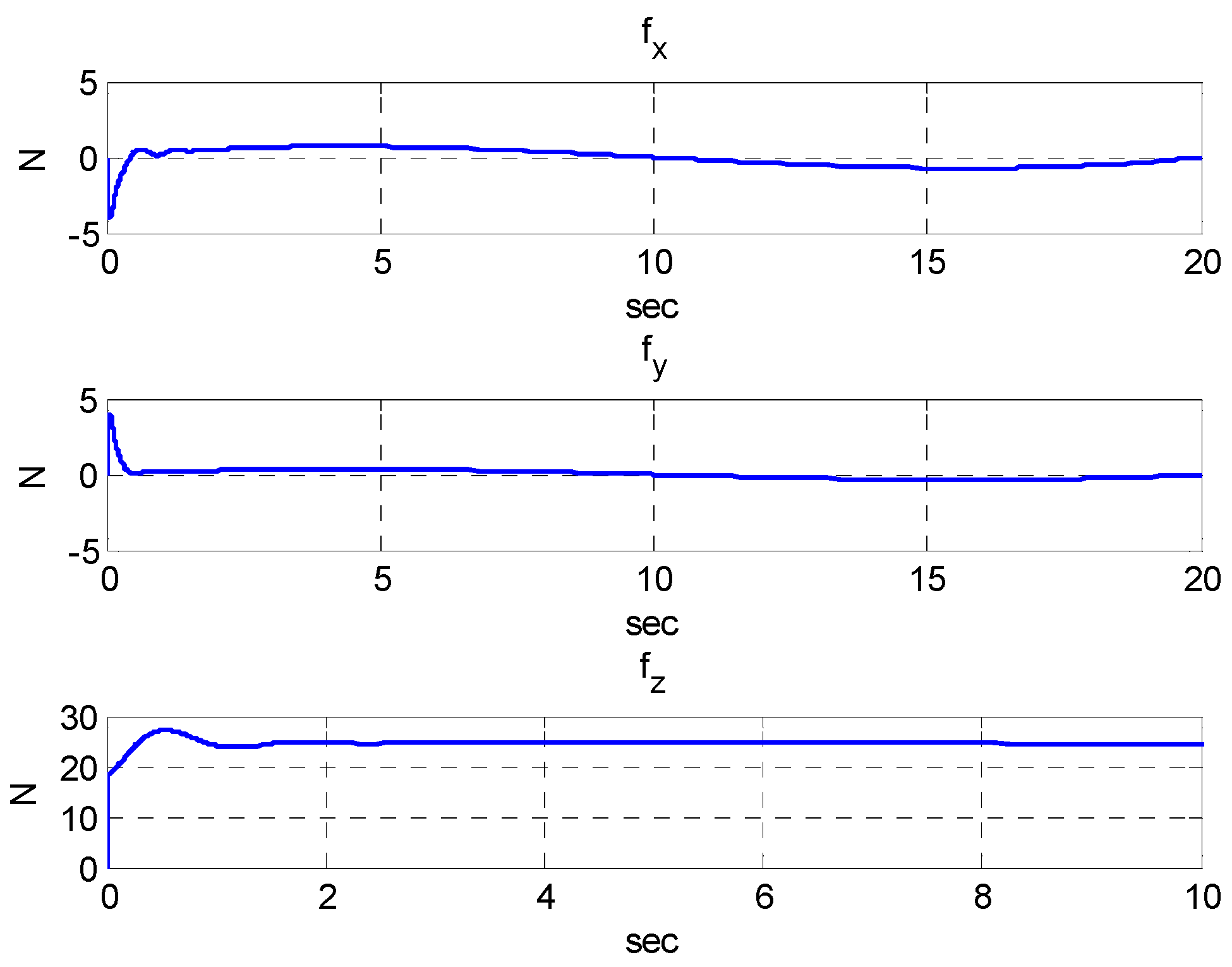

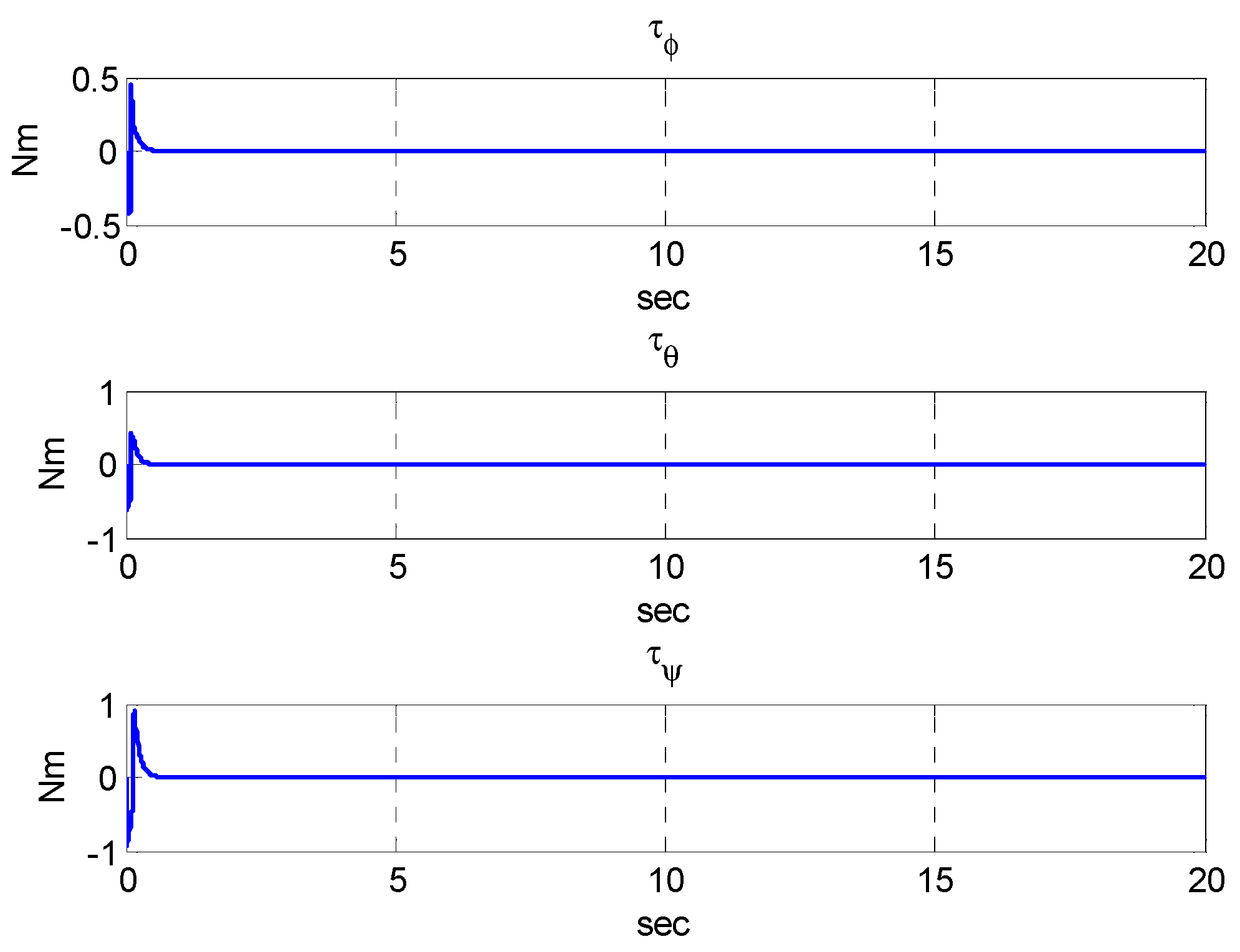

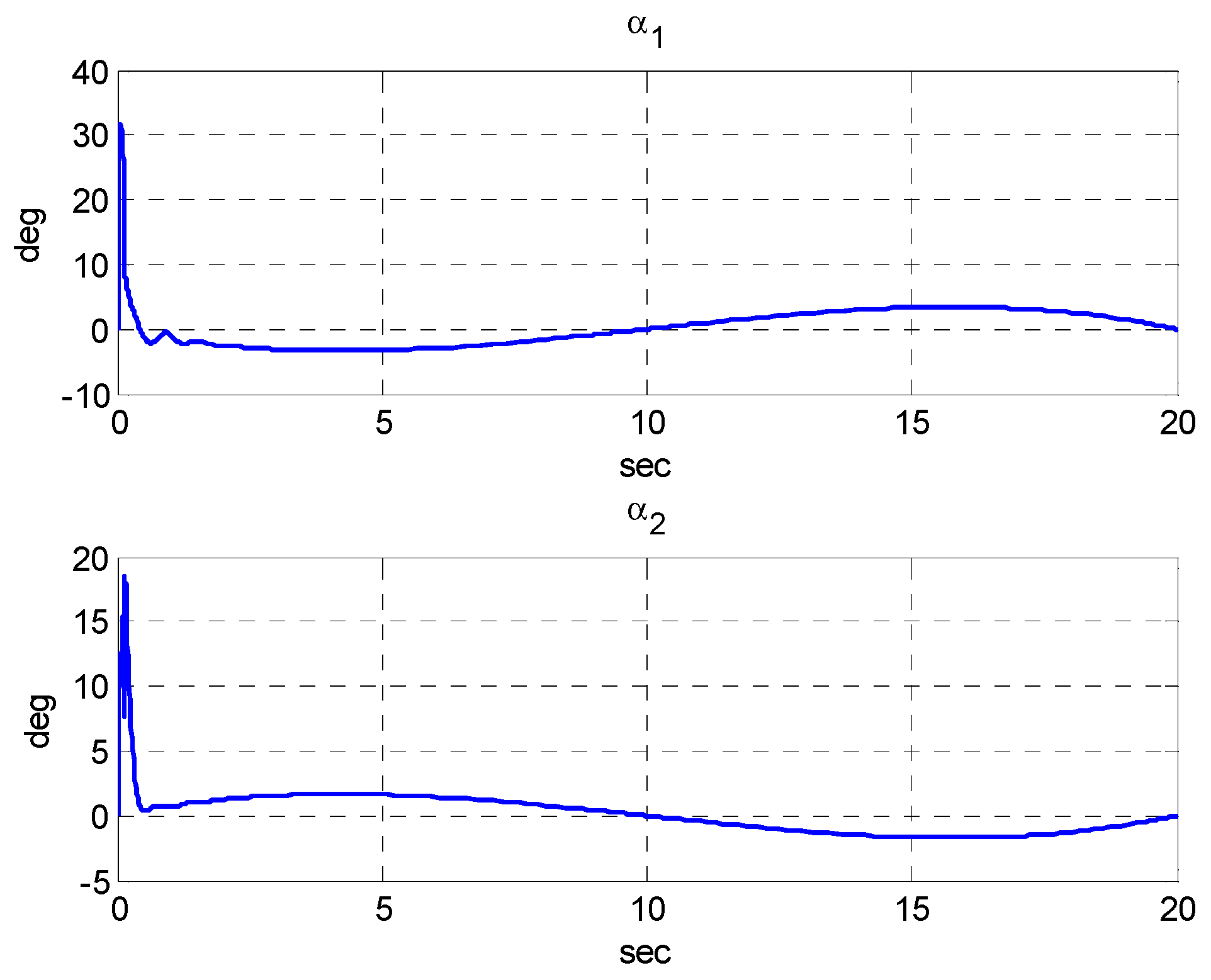

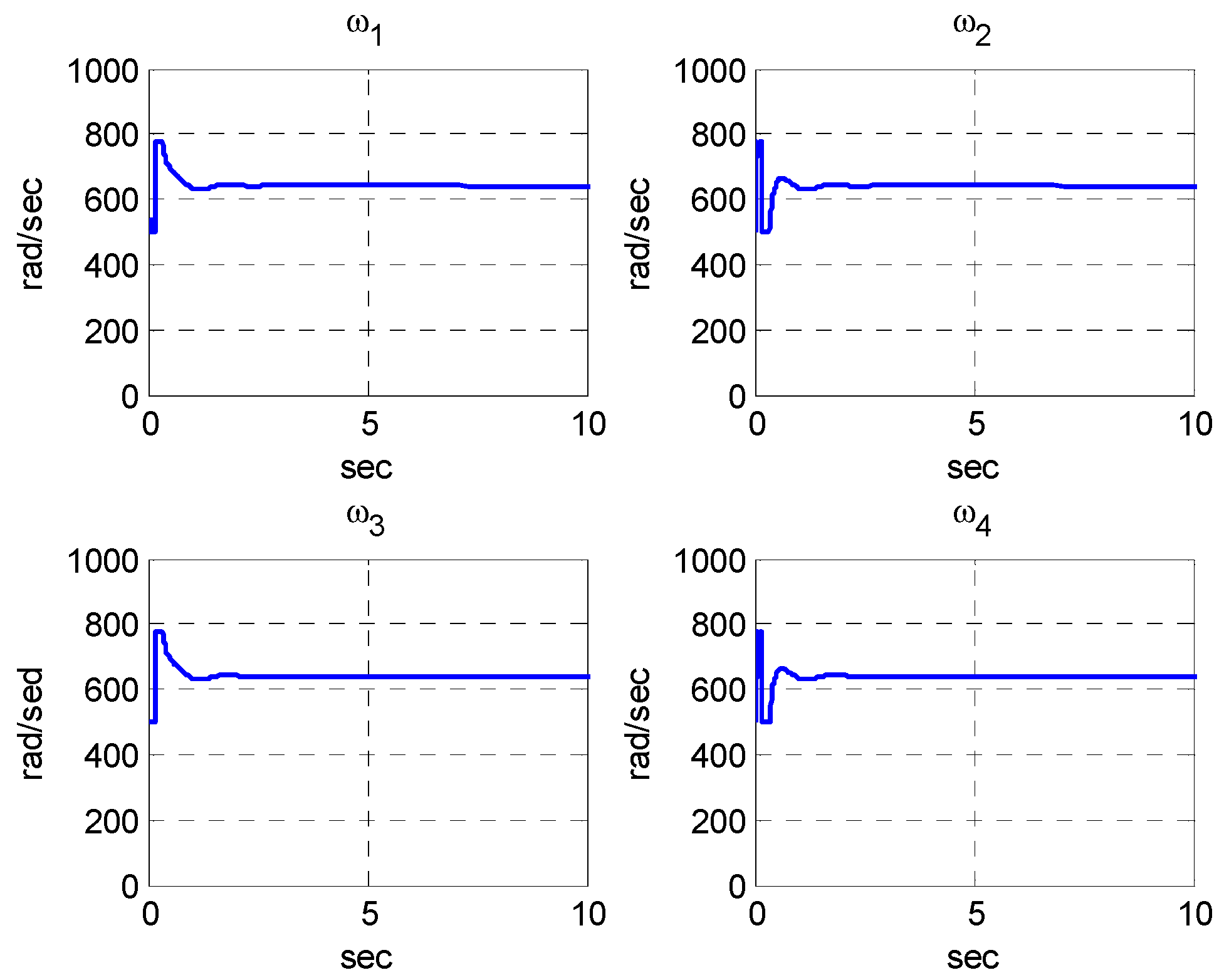

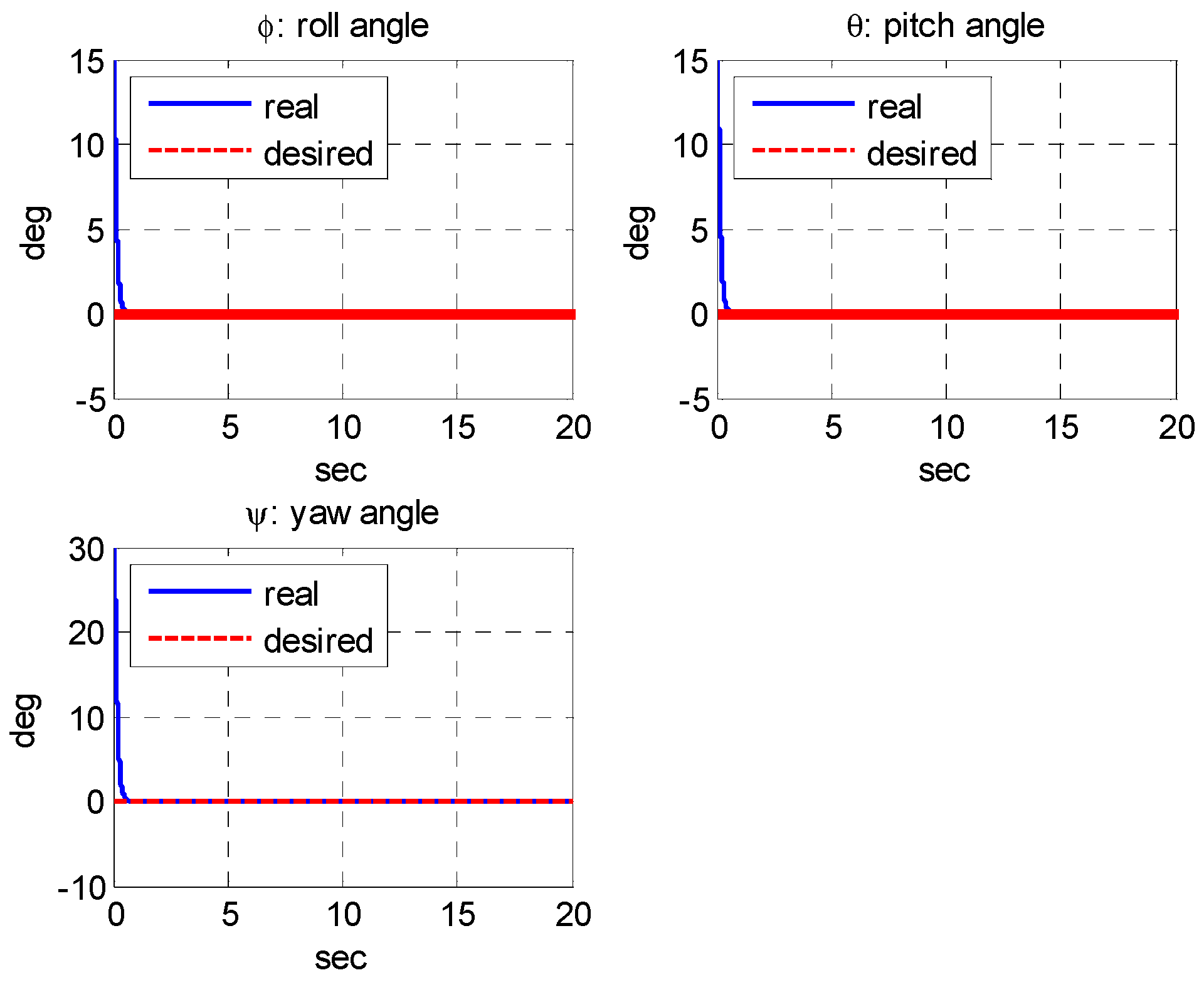

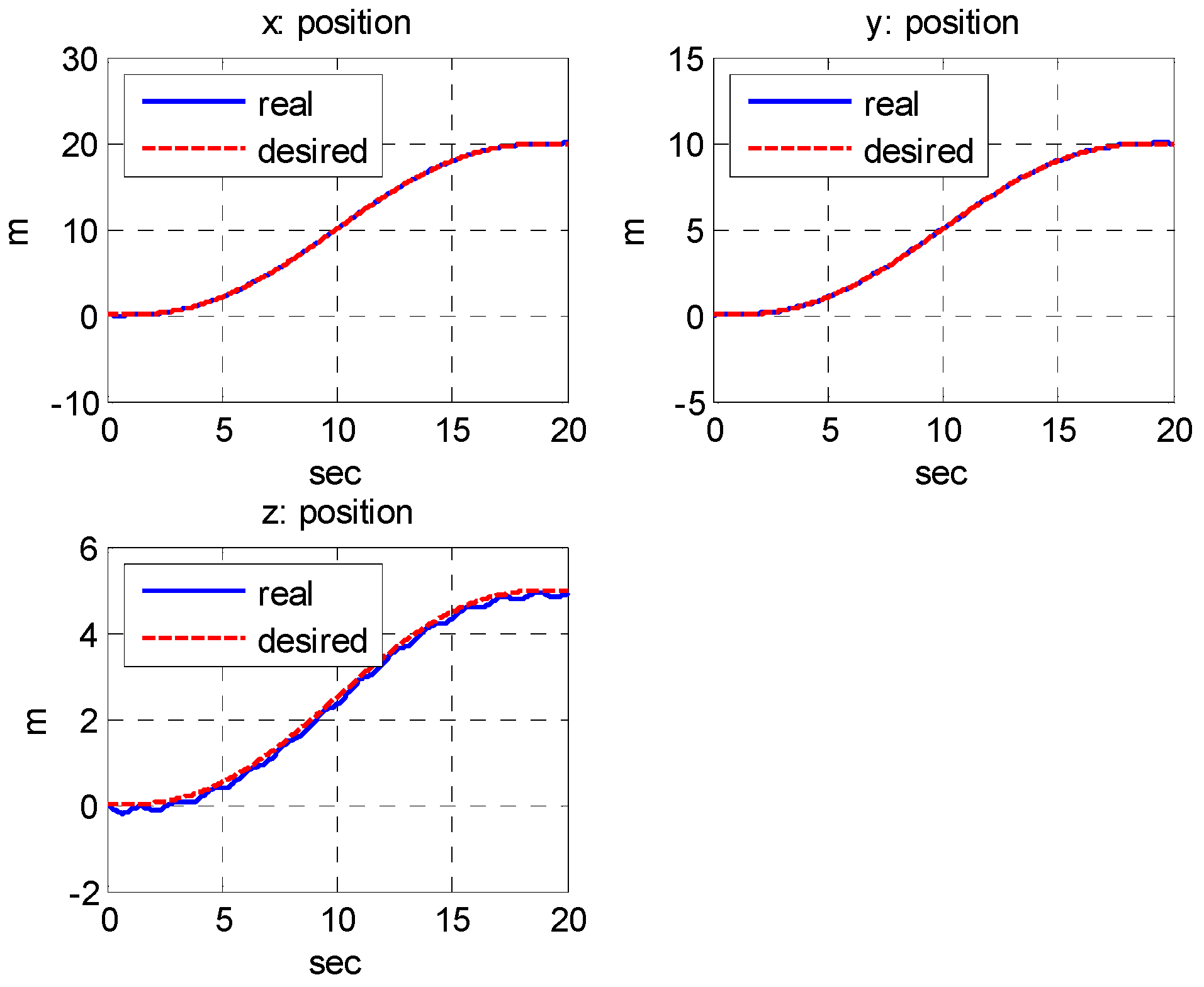

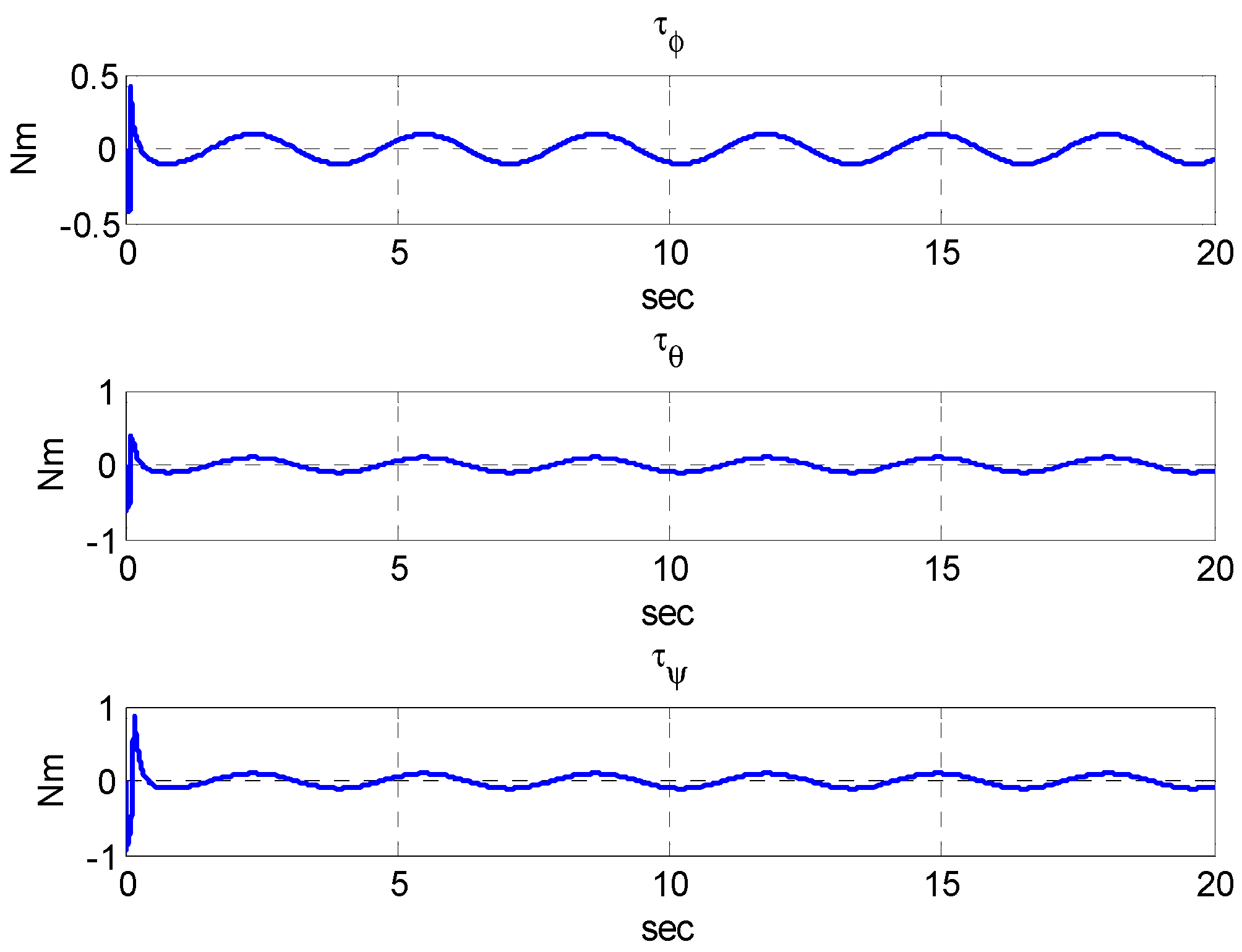

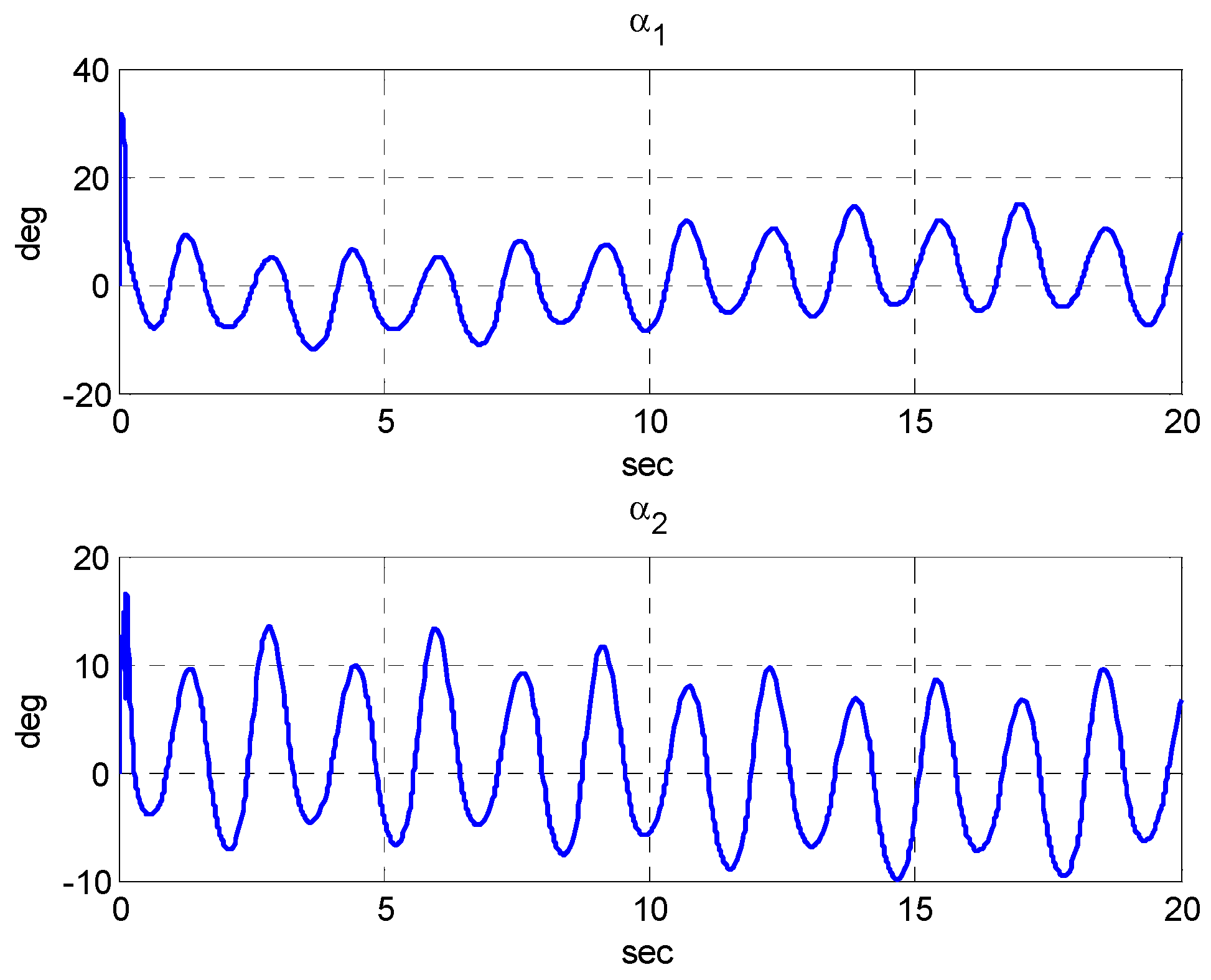

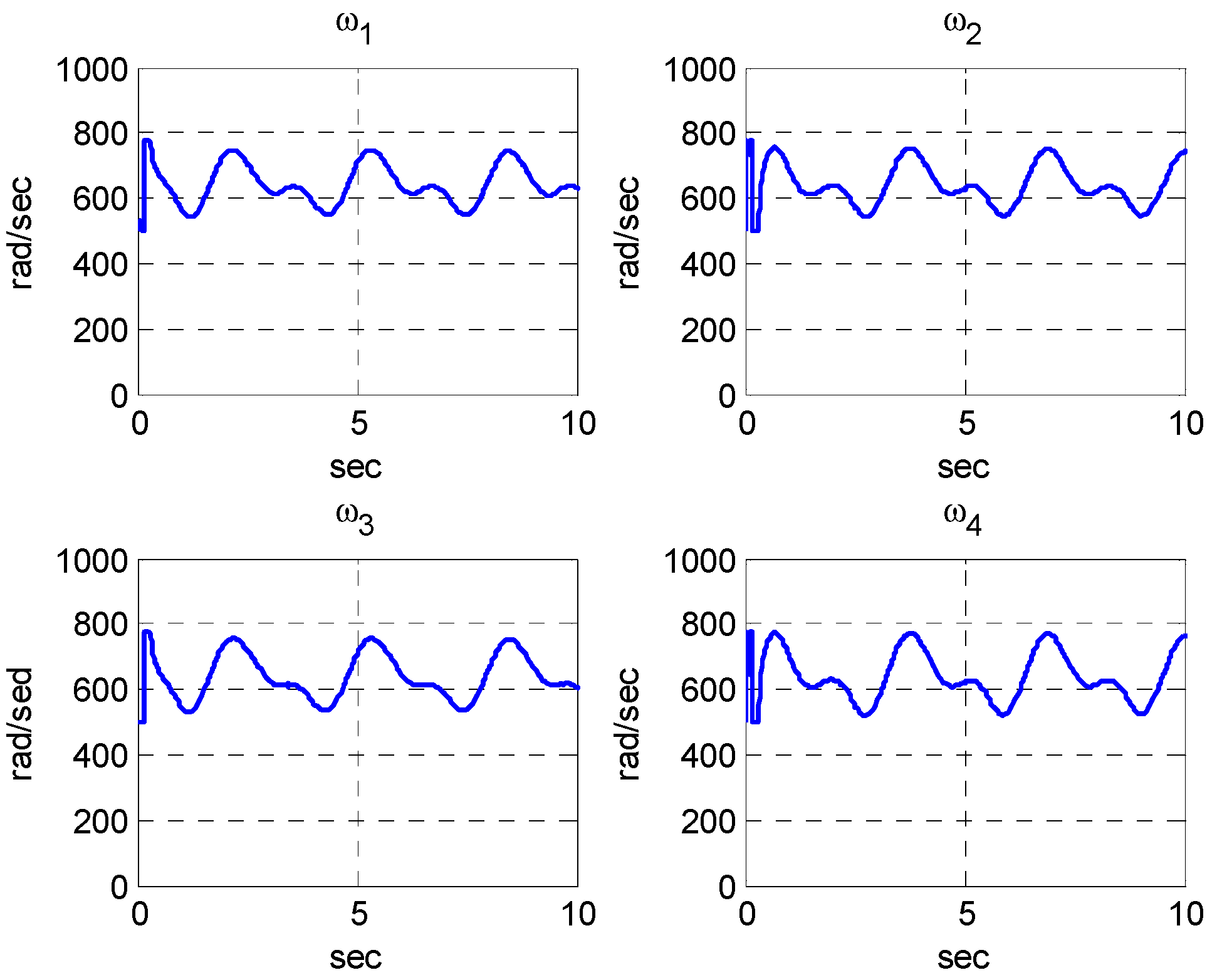

5.2. Simulation Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

References

- Mahony, R.; Kumar, V.; Corke, P. Multirotor Aerial Vehicles: Modeling, Estimation, and Control of Quadrotor. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2012, 19, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Q. Introduction to Multicopter Design and Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Colorado, R.; Aguilar, L.T. Robust PID control of quadrotors with power reduction analysis. ISA Trans. 2020, 98, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, L.L.; Leal, L.; Oliveira, T.R.; Cunha, J.P.V.S.; Revoredo, T.C. Unmanned Quadcopter Control Using a Motion Capture System. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2016, 14, 3606–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankaran, V.P.; Azid, S.I.; Mehta, U.; Fagiolini, A. Improved Performance in Quadrotor Trajectory Tracking Using MIMO PI-D Control. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 110646–110660. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Kim, H.J.; Sastry, S. Feedback Linearization vs. Adaptive SMC for a Quadrotor Helicopter. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2009, 7, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satici, A.C.; Poonawala, H.; Spong, M.W. Robust Optimal Control of Quadrotor UAVs. IEEE Access 2013, 1, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, N.; An, H.; Fidan, B. Backstepping-based adaptive control of a quadrotor UAV with guaranteed following capability. ISA Trans. 2020, 105, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Cheol, C.; Hyo-Sung, A. Nonlinear Control of Quadrotor for Point Following: Actual Implementation and Experimental Tests. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 20, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Perozzi, G.; Efimov, D.; Biannic, J.-M.; Planckaert, L. Path following for a quadrotor under wind perturbations: SMC with state-dependent gains. J. Frankl. Inst. 2018, 355, 4809–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Xia, Y.; Zhai, D.-H.; Ma, D. Adaptive prescribed capability terminal sliding mode attitude control for quadrotor under input saturation. IET Control Theory Appl. 2020, 14, 2473–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnard, L.; Shtessel, Y.B.; Landrum, B. Quadrotor vehicle control via SMCler driven by sliding mode perturbation observer. J. Frankl. Inst. 2012, 349, 658–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo, J.A., Jr.; Santos, D.A.; Oliveira, T.R. Attitude Tracking Control for a Quadrotor Aerial Robot Using Adaptive Sliding Modes. In Proceedings of the XLI Ibero-Latin-American Congress on Computational Methods in Engineering (ABMEC), Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 16–19 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.; Liu, P.X.; El Saddik, A. Robust Control of Four-Rotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle With Perturbation Uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierks, T.; Jagannathan, S. Output Feedback Control of a Quadrotor UAV Using Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2010, 21, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Ye, H.; Xue, W.; Yang, X. Improved Reinforcement Learning Using Stability Augmentation With Application to Quadrotor Attitude Control. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 67590–67604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xian, B. Exponential Regulation Control of a Quadrotor Unmanned Aerial Vehicle With a Suspended Payload. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2020, 28, 2762–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, A. Principles of 2-sliding mode design. Automatica 2007, 43, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, A. Sliding order and sliding accuracy in SMC. Int. J. Control 1993, 58, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkin, V.I.; Poznyak, A.S. Adaptive SMC with application to super-twist algorithm: Equivalent control method. Automatica 2013, 49, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Osorio, M. Strict Lyapunov functions for the super-twisting algorithm. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pico, J.; Pico-Marco, E.; Vignoni, A.; De Battista, H. Stability preserving maps for finite-time convergence: Super-twisting sliding-mode algorithm. Automatica 2013, 49, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkin, V. On convergence time and perturbation rejection of super-twisting control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2013, 58, 2013–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, A.; Benallegue, A.; Orlov, Y. Exact linearization and sliding mode observer for a quadrotor unmanned aerial vehicle. Int. J. Robot. Autom. 2006, 21, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beballegue, A.; Mokhtari, A.; Fridman, L. High-order sliding-mode observer for a quadrotor UAV. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2008, 18, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauersfeld, L.; Spannagl, L.; Ducard, G.J.J.; Onder, C.H. MPC Flight Control for a Tilt-Rotor VTOL Aircraft. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2021, 57, 2395–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryll, M.; Bülthoff, H.H.; Giordano, P.R. A Novel Overactuated Quadrotor UnmannedAerial Vehicle: Modeling, Control, and Experimental Validation. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2015, 23, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, M.-D.; Hamel, T.; Morin, P.; Samson, C. Control of VTOL vehicles with thrust-tilting augmentation. Automatica 2015, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, R.; Goerres, J.; Aarts, R.; Engelen, J.B.C.; Stramigioli, S. Fully Actuated Multirotor UAVs: A Literature Review. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2020, 27, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Tan, X.; Kocer, B.B.; Yang, E.; Kovac, M. TiltDrone: A Fully-Actuated Tilting Quadrotor Platform. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 6845–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J.; Johnson, J.; Beard, R.W. State-Dependent LQR Control for a Tilt-Rotor UAV. In Proceedings of the 2020 American Control Conference (ACC), Denver, CO, USA, 1–3 July 2020; pp. 4175–4181. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yih, C.-C.; Wu, S.-J. Sliding Mode Path following and Control Allocation of a Tilt-Rotor Quadcopter. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11088. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111088

Yih C-C, Wu S-J. Sliding Mode Path following and Control Allocation of a Tilt-Rotor Quadcopter. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(21):11088. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111088

Chicago/Turabian StyleYih, Chih-Chen, and Shih-Jeh Wu. 2022. "Sliding Mode Path following and Control Allocation of a Tilt-Rotor Quadcopter" Applied Sciences 12, no. 21: 11088. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111088

APA StyleYih, C.-C., & Wu, S.-J. (2022). Sliding Mode Path following and Control Allocation of a Tilt-Rotor Quadcopter. Applied Sciences, 12(21), 11088. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111088